Mullins L.J. Management and organisational behaviour, Seventh edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

every situation, but instead seeks to explain how one attribute or characteristic

depends upon another.’

3

The most appropriate structure is dependent, therefore, upon the contingencies of

the situation for each individual organisation. These situational factors account for

variations in the structure of different organisations.

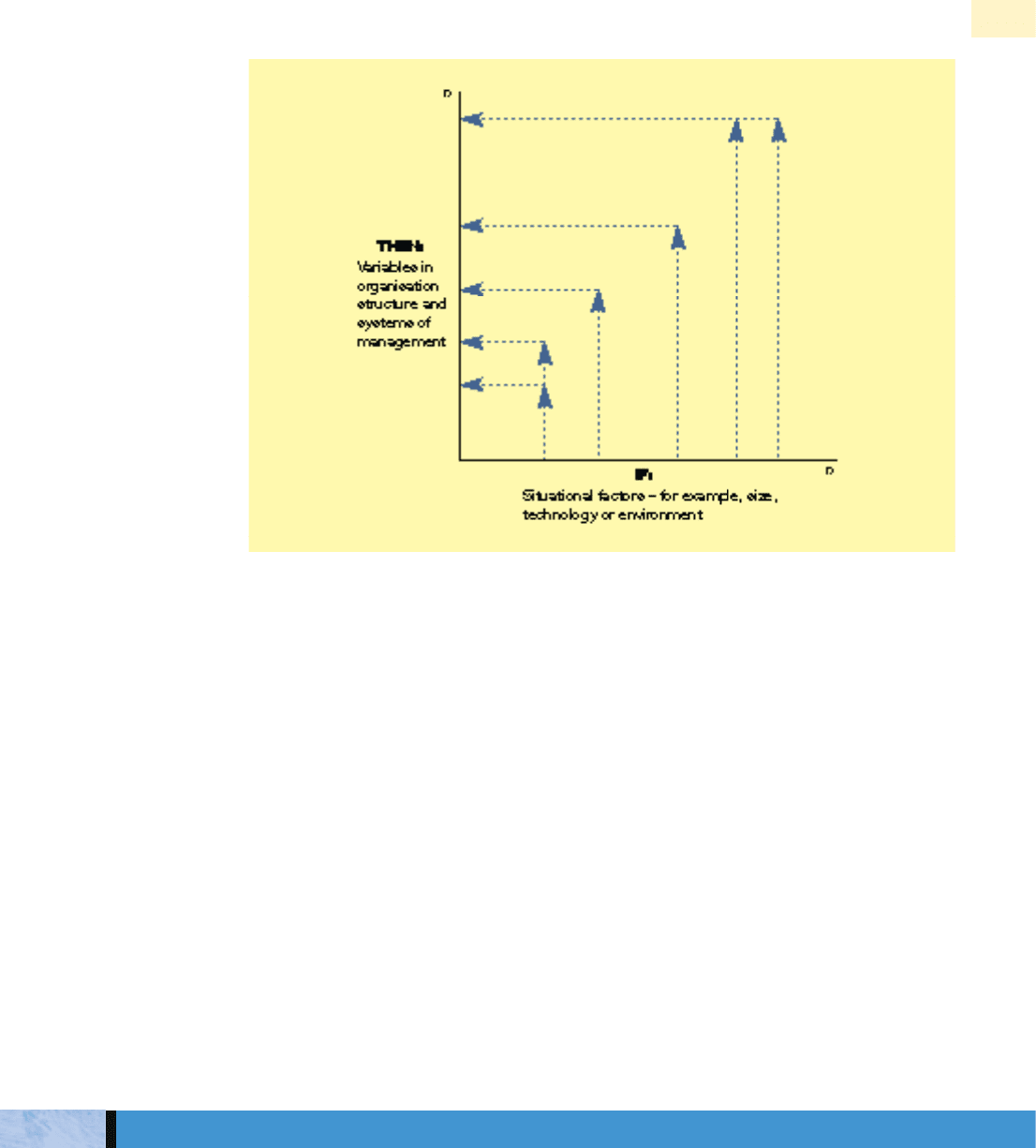

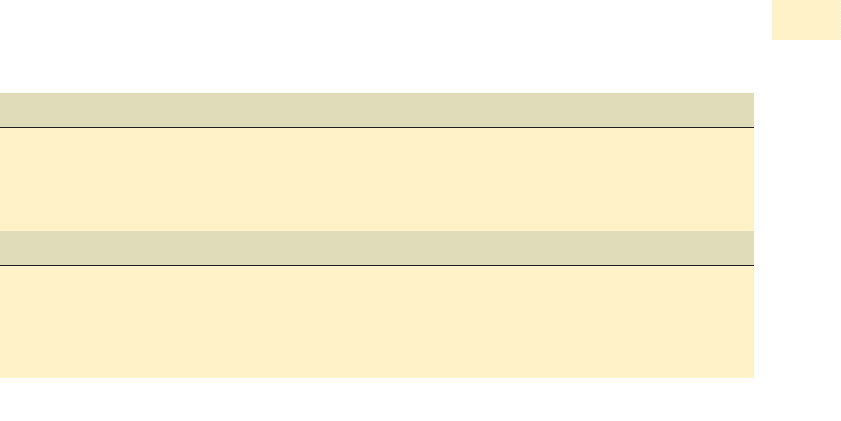

The contingency approach can be seen as a form of ‘if–then’ matrix relationship.

4

If

certain situational factors exist, then certain variables in organisation structure and sys-

tems of management are most appropriate. A simplified illustration of contingency

relationships is given in Figure 16.1.

Situational factors may be identified in a number of ways. The more obvious bases

for comparison include the type of organisation and its purpose (which was discussed

in Chapter 4); power and control; history; and the characteristics of the members of

the organisation such as their abilities, skills and experience and their needs and moti-

vations. The choice of structure can also be influenced by the preferences of top

management.

5

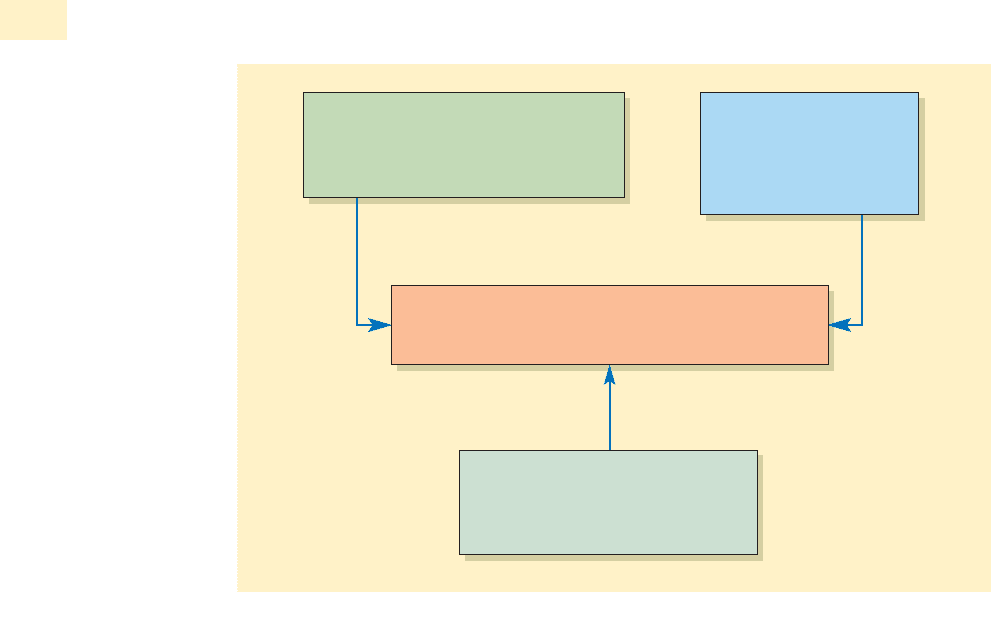

Another significant contingent factor is the culture of the organisation,

which is discussed in Chapter 22. Other important variables are size, technology and

environment. A number of studies have been carried out into the extent to which

these contingency factors influence organisational design and effectiveness. Among

the most significant contingency influences are those shown in Figure 16.2.

The size of an organisation has obvious implications for the design of its structure. In

the very small organisations there is little need for a formal structure. With increasing

size, however, and the associated problems of the execution of work and management

of staff, there are likely to be more formalised relationships and greater use of rules and

CHAPTER 16 PATTERNS OF STRUCTURE AND WORK ORGANISATION

635

An ‘if–then’

relationship

Figure 16.1 The ‘if–then’ contingency relationship

SIZE OF ORGANISATION

standardised procedures. Size explains best many of the characteristics of organisation

structure, for example the importance of standardisation through rules and procedures

as a mechanism for co-ordination in larger organisations.

Size, however, is not a simple variable. It can be defined and measured in different

ways, although the most common indication of size is the number of persons

employed by the organisation. There is the problem of distinguishing the effects of size

from other organisational variables. Furthermore, there is conflicting evidence on the

relationship of size to the structure and operation of the organisation.

There is continuing debate, however, about the importance of size as a structural

variable. Despite the often claimed advantages of large size and resultant economies of

scale, Peters and Waterman put forward a strong case for small size companies.

Activities that achieve cost efficiencies, on the other hand, are reputedly best done in large facili-

ties to achieve economies of scale. Except that this is not the way it works in the excellent

companies. In excellent companies, small in almost every case is beautiful … It holds for plants,

for project teams, for divisions – for the entire company … Small, quality, excitement, autonomy –

and efficiency – are all words that belong on the same side of the coin.

6

In a study of the effects of size on the rate of growth and economic performance, Child

acknowledges the tendency for increased size to be associated with increased bureau-

cracy. He argues that the more bureaucratised, larger organisations perform better than

the less bureaucratised, larger organisations. Child found that:

Much as critics may decry bureaucracy … the more profitable and faster growing companies, in

the larger size category of 2000 employees and above, were those that had developed this type

of organization. The larger the company, the greater the association between more bureaucracy

and superior performance. At the other end of the scale, among small firms of only a hundred or

so employees, the better performers generally managed with very little formal organization.

7

636

PART 6 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURES

The ‘if–then’ contingency relationship

Situational factors influencing structure and design,

management systems and organisational performance

Other influences

for example:

•preference of top management

•organisational culture

Other major variables

for example:

• size

• technology

• environment

Common bases for comparison

for example:

• type of organisation and its purpose

• characteristics of its members

Figure 16.2 Main influences on the contingency approach

Size and

economic

performance

There is a continuing debate about the comparative advantages of large and small

organisations; or whether ‘bigger is best’ or ‘small is beautiful’. The conclusion appears

to be that managers should attempt to follow a middle line in terms of the size of the

organisations and that complexity rather than size may be a more influential variable.

8

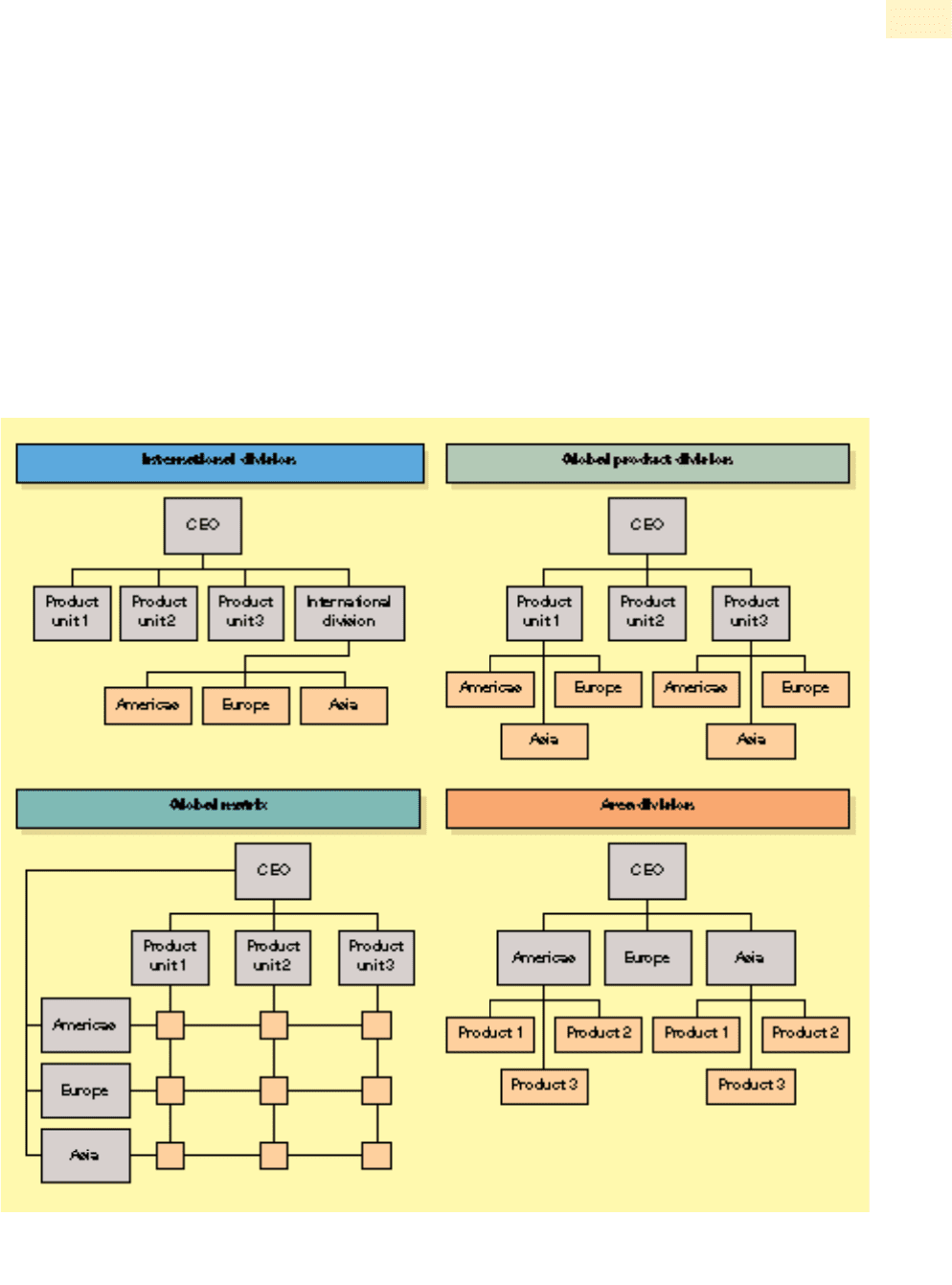

Birkinshaw draws attention to size as a particular feature of the structures of global

companies. ‘The reality is that global companies end up being perceived as complex,

slow-moving and bureaucratic. The challenge for top managers lies in minimizing

these liabilities, while retaining the benefits of size.’ The pure matrix (discussed in

Chapter 15) with equal stress on two lines of accountability does not work. Attention

must be given to strong but informal horizontal relationships and country managers in

developing markets. The organisation of a global company depends on a host of fac-

tors including number of businesses and countries in which it operates, the type of

industry, location of major customers, and its own heritage. Birkinshaw identifies four

(simplified) models for the structure of a global company.

9

(See Figure 16.3.).

CHAPTER 16 PATTERNS OF STRUCTURE AND WORK ORGANISATION

637

Figure 16.3 Four models for global company structure

Reprinted with permission from Julian Birkinshaw, ‘The structures behind global companies’, in Pickford, J. (ed.) Mastering Management 2.0, Financial Times Prentice

Hall (2001), p. 76, with permission from Pearson Education Ltd.

Two major studies concerning technology are by:

■ Woodward – patterns of organisation, production technology and business success;

and

■ Perrow – main dimensions of technology and organisation structure.

A major study of the effects of technology on organisation structure was carried out by

Joan Woodward.

10

Her pioneering work presents the results of empirical study of 100

manufacturing firms in south-east Essex and the relationships between the application

of principles of organisation and business success. The main thesis was:

that industrial organizations which design their formal organizational structures to fit the type of

production technology they employ are likely to be commercially successful.

11

Information was obtained from each of the firms under the four headings of:

1 history, background and objectives;

2manufacturing processes and methods;

3forms and routines used in the organisation and operation of the firm;

4 information relating to an assessment of commercial success.

The firms were divided into nine different types of production systems, from least to

most technological complexity, with three main groupings of:

■ unit and small batch production

■ large batch and mass production

■ process production

The research showed that the firms varied considerably in their organisation structure

and that many of the variations appeared to be linked closely with differences in man-

ufacturing techniques.

Organisational patterns were found to be related more to similarity of objectives and

production techniques than to size, type of industry, or the business success of the

firm. Among the organisational characteristics showing a direct relationship to tech-

nology were span of control and levels of management, percentage of total turnover

allocated to wages and salaries, ratio of managers to total personnel, and ratio of cleri-

cal and administrative staff to manual workers. The more advanced the technology the

longer the length of the line. Details of levels of management and span of control are

summarised in Table 16.1.

Woodward acknowledges that technology is not the only variable which affects

organisation but is one that could be isolated more easily for study. She does, however,

draw attention to the importance of technology, organisation and business success.

The figures relating to the span of control of the chief executive, the number of levels in the line of

command, labour costs, and the various labour ratios showed a similar trend. The fact that organ-

izational characteristics, technology and success were linked together in this way suggested that

not only was the system of production an important variable in the determination of organiza-

tional structure, but also that one particular form of organization was most appropriate to each

system of production. In unit production, for example, not only did short and relatively broad

based pyramids predominate, but they also appeared to ensure success. Process production, on

the other hand, would seem to require the taller and more narrowly based pyramid.

12

638

PART 6 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURES

TECHNOLOGY

THE WOODWARD STUDY

Patterns of

organisation

and technology

There appeared to be no direct link between principles of organisation and business

success. As far as organisation was concerned, the 20 outstandingly successful firms

had little in common. The classical approach appeared to fail in providing a direct and

simple basis for relating organisational structure and business success. There was,

however, a stronger relationship between organisation structure and success

within each of the three main groupings of production systems.

Twenty firms were placed in the ‘above average’ classification of business success –

five unit production, five mass production, six process production – and the remainder

with combined systems. Seventeen firms were classified as ‘below average’ – five unit

production, six mass production, four process production, and two with combined sys-

tems. It was found that within each production grouping the successful firms had

common organisational characteristics which tended to be clustered round the medi-

ans for the grouping as a whole. Figures for those firms classified as ‘below average’

tended to be at the extremes of the range.

Another important finding of Woodward’s study was the nature of the actual cycle of

manufacturing and the relationship between three key ‘task’ functions of develop-

ment, production and marketing. The most critical of these functions varied according

to the type of production system. (See Table 16.2.)

■ Unit and small batch. Production was based on firm orders only with marketing

the first activity. Greater stress was laid on technical expertise, and the quality and

efficiency of the product. Research and development were the second, and most crit-

ical, activities. The need for flexibility, close integration of functions and frequent

personal contacts meant that an organic structure was required.

■

Large batch and mass. Production schedules were not dependent directly on firm

orders. The first phase of manufacturing was product development, followed by pro-

duction which was the most important function, and then third, marketing. The three

functions were more independent and did not rely so much on close operational rela-

tionships among people responsible for development, production and sales.

■ Process. The importance of securing a market meant that marketing was the central

and critical activity. Products were either impossible or difficult to store, or capacity

for storage was very limited. The flow of production was directly determined, there-

fore, by the market situation. Emphasis of technical knowledge was more on how

products could be used than on how they could be made.

CHAPTER 16 PATTERNS OF STRUCTURE AND WORK ORGANISATION

639

Number of levels of management authority

Number of firms Type of production Range of levels Median

24 Unit and small batch 2 to 4 3

31 Large batch and mass production 3 to 8 or more 4

25 Process production 4 to 8 or more 6

Average span of control of first line supervisor

Number of firms Type of production Range of span Median

24 Unit and small batch Less than 10 to 51–60 23

31 Large batch and mass production 11–20 to 81–90 49

25 Process production Less than 10 to 31–40 13

Table 16.1 Summary of levels of management and span of control

(Reproduced with permission from Woodward. J. Industrial Organization: Theory and Practice, Second edition, Oxford University Press

(1980) pp. 52 and 69.)

Principles of

organisation

and business

success

Relationship

between

development,

production and

marketing

A subsequent study by Zwerman supported, very largely, the findings of Woodward.

Zwerman’s study involved a slightly different sample of organisations and was carried

out in Minneapolis in the USA.

13

In other respects, however, the study attempted to

replicate Woodward’s work. Zwerman reached a similar conclusion, that the type of

production technology was related closely to variations in organisation structure.

Another study in Japan also supported the findings of Woodward and the relationship

between technology and structure.

14

However, a further study by Collins and Hull of 95 American manufacturing firms

questioned the extent to which span of control is a by-product of main types of pro-

duction technology. Variations in the span of control of production operations were

attributed to the underlying effects of size, task complexity and automation. Collins

and Hull suggest that the technology versus size debate has moved beyond an

‘either–or’ proposition to a ‘both–and’ proposition.

15

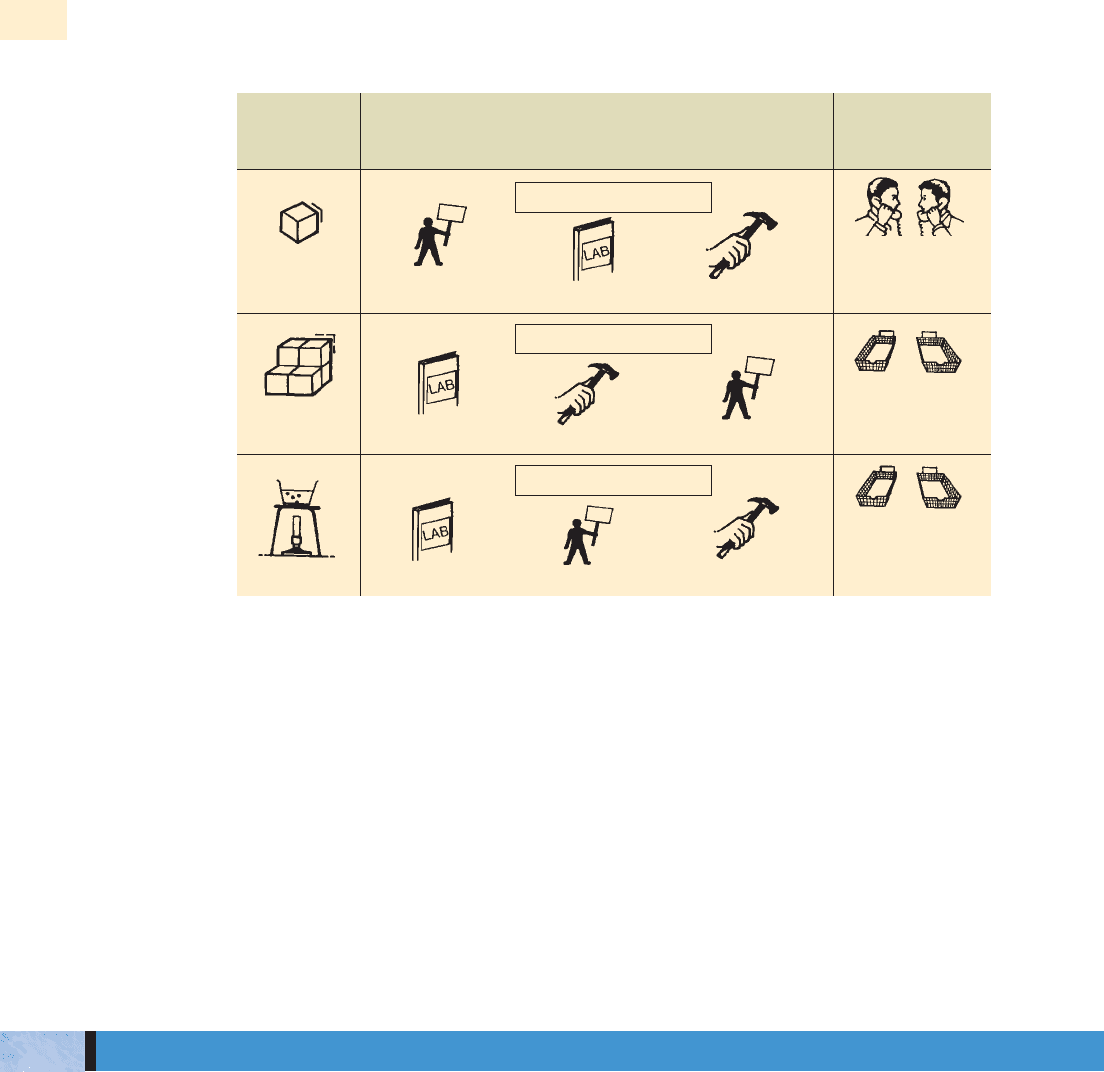

The work by Woodward was extended by Perrow who drew attention to two major

dimensions of technology:

■ the extent to which the work task is predictable or variable; and

■ the extent to which technology can be analysed.

16

Variability refers to the number of exceptional or unpredictable cases and the extent to

which problems are familiar. For example, a mass production factory is likely to have

only a few exceptions but the manufacture of a designer range of clothing would have

many exceptional and unpredictable cases. The analysis of technology refers to the

640

PART 6 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURES

Production Manufacturing cycle Relationship

systems between

task functions

Day-to-day

Unit and operational

small batch Marketing Development Production relationship

Normally

Large batch exchange of

and mass Development Production Marketing information only

Normally

exchange of

Process Development Marketing Production information only

Table 16.2 Characteristics of production systems

(Reproduced with permission from Woodward, J. Industrial Organization: Theory and Practice, Second edition, Oxford University Press

(1980) p.128.)

Most critical function

Most critical function

Most critical function

Subsequent

studies

MAJOR DIMENSIONS OF TECHNOLOGY: THE WORK OF PERROW

extent to which the task functions are broken down and highly specified, and the extent

to which problems can be solved in recognised ways or by the use of routine procedures.

Combining the two dimensions provides a continuum of technology from Routine

→ Non-routine. With non-routine technology there are a large number of exceptional

cases involving difficult and varied problem-solving. The two dimensions of variability

and the analysis of problems can also be represented as a matrix. (See Figure 16.4.)

The classification of each type of technology relates to a particular organisation structure.

Perrow suggests that by classifying organisations according to their technology and pre-

dictability of work tasks, we should be able to predict the most effective form

of structure. Variables such as the discretion and power of sub-groups, the basis of co-ordi-

nation and the interdependence of groups result from the use of different technologies.

In the routine type of organisation there is minimum discretion at both the tech-

nical and supervisory levels, but the power of the middle management level is high;

co-ordination is based on planning; and there is likely to be low interdependence

between the two groups. This arrangement approaches a bureaucratic structure.

In the non-routine type of organisation there is a high level of discretion and

power at both the technical and supervisory levels; co-ordination is through feedback;

and there is high group interdependence. This model resembles an organic structure.

Two important studies which focused not just on technology but on the effects of

uncertainty and a changing external environment on the organisation, and its man-

agement and structure, are those by:

■ Burns and Stalker – divergent systems of management practice, ‘mechanistic’ and

‘organic’; and

■ Lawrence and Lorsch – the organisation of specific departments, and the extent of

‘differentiation’ and ‘integration’.

CHAPTER 16 PATTERNS OF STRUCTURE AND WORK ORGANISATION

641

Figure 16.4 Matrix of technology variables

(Adapted from Perrow, C. Organisational Analysis: A Sociological View, Tavistock Publications (1970) p. 78. and Mitchell, T. R. People in

Organisations, Second edition. McGraw-Hill (1982) p. 32. Reproduced with permission from the McGraw-Hill Companies Inc.)

Technology

and structure

ENVIRONMENT

The study by Burns and Stalker was an analysis of 20 industrial firms in the United

Kingdom and the effects of the external environment on their pattern of management

and economic performance.

17

The firms were drawn from a number of different indus-

tries: a rayon manufacturer; a large engineering company; Scottish firms attempting to

enter the electronics field; and English firms operating in varying sectors of the elec-

tronics industry.

Mechanistic and organic systems

From an examination of the settings in which the firms operated, Burns and Stalker

distinguished five different kinds of environments ranging from ‘stable’ to ‘least pre-

dictable’. They also identified two divergent systems of management practice and

structure – the ‘mechanistic’ system and the ‘organic’ system. These represented the polar

extremes of the form which such systems could take when adapted to technical and

commercial change. Burns and Stalker suggested that both types of system represented

a ‘rational’ form of organisation which could be created and maintained explicitly and

deliberately to make full use of the human resources in the most efficient manner

according to the circumstances of the organisation.

The mechanistic system is a more rigid structure and more appropriate to stable

conditions. The characteristics of a mechanistic management system are similar to

those of bureaucracy.

The organic system is a more fluid structure appropriate to changing conditions. It

appears to be required when new problems and unforeseen circumstances arise con-

stantly and require actions outside defined roles in the hierarchical structure.

A summary of the characteristics of mechanistic and organic organisations is pro-

vided by Litterer.

18

(See Table 16.3.) The mechanistic organisation is unable to deal

adequately with rapid change; it is therefore more appropriate for stable environmental

conditions. An example might be a traditional high-class and expensive hotel operat-

ing along classical lines with an established reputation and type of customer. However,

major fast-food chains which tend to operate along the lines of scientific management

(discussed in Chapter 3) also require a mechanistic structure. By contrast, a holiday or

tourist hotel with an unpredictable demand, offering a range of different functions and

with many different types of customers, requires an organic structure.

Although the organic system is not hierarchical in the same sense as the mechanistic

system, Burns and Stalker emphasise that it is still stratified, with positions differenti-

ated according to seniority and greater expertise. The location of authority, however,

is by consensus and the lead is taken by the ‘best authority’, that is the person who is

seen to be most informed and capable. Commitment to the goals of the organisation

is greater in the organic system, and it becomes more difficult to distinguish the formal

and informal organisation. The development of shared beliefs in the values and goals

of the organisation in the organic system runs counter to the co-operation and moni-

toring of performance achieved through the chain of hierarchical command in the

mechanistic system.

A study of 42 voluntary church organisations in the USA found that as the organisa-

tions became more mechanistic, the intrinsic motivation, sense of freedom and

self-determination of their members decreased.

19

Burns and Stalker point out that there are intermediate stages between the two

extreme systems which represent not a dichotomy but a polarity. The relationship

between the mechanistic and organic systems is not rigid. An organisation

moving between a relatively stable and a relatively changing environment may

also move between the two systems.

642

PART 6 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURES

THE BURNS AND STALKER STUDY

Location of

authority

According to Reigle, knowledge workers in today’s high technology organisations

require environments with organic characteristics. As technology continues to expand

throughout the world, an organic organisational culture will become increasingly

important. In order to retain highly skilled knowledge workers, managers should

undertake investigations using an organisational culture assessment (OCA) to measure

whether their organisations exhibit mechanistic or organic cultures. The OCA is based

on five cultural elements of: language; tangible artefacts and symbols; patterns of

behaviour, rites and rituals; espoused values; and beliefs and underlying assumptions.

20

Organisations tend towards mechanistic or organic, and many organisations will be

hybrid – that is, a mix of both mechanistic and organic structures – and often this is an

uneasy mix which can lead to tension and conflict! For example, a group of people

engaged on a set of broad functional activities may prefer, and perform best in, an

organic structure; while another group tends to prefer a mechanistic structure and to

work within established rules, systems and procedures. The different perceptions of

appropriate organisational styles and working methods present a particular challenge

to management. There is need for a senior member of staff, in an appropriate position

CHAPTER 16 PATTERNS OF STRUCTURE AND WORK ORGANISATION

643

Mechanistic Organic

High, many and sharp SPECIALISATION Low, no hard boundaries,

differentiations relatively few different jobs

High, methods spelled STANDARDISATION Low, individuals decide own

out methods

Means ORIENTATION Goals

OF MEMBERS

By superior CONFLICT Interaction

RESOLUTION

Hierarchical, based on PATTERN OF Wide net based upon

implied contractual AUTHORITY CONTROL common commitment

relation AND COMMUNICATION

At top of LOCUS OF SUPERIOR Wherever there is skill

organisation COMPETENCE and competence

Vertical INTERACTION Lateral

Directions, orders COMMUNICATION Advice, information

CONTENT

To organisation LOYALTY To project and group

From organisational PRESTIGE From personal

position contribution

Table 16.3 Characteristics of mechanistic and organic organisations

(Reprinted with the permission of the author from Litterer, J. A. The Analysis of Organisations, Second edition, Wiley (1973) p. 339.)

Organic

cultures for

high technology

organisations

‘MIXED’ FORMS OF ORGANISATION STRUCTURE

in the hierarchy and who has the respect of both groups, to act in a bridging role and

to help establish harmony between them.

21

A typical example of a hybrid organisation could be a university with differences in

perception between the academic staff and the non-teaching staff. The non-teaching

staff have an important function in helping to keep the organisation operational and

working effectively, and may fail to understand why academics appear to find it diffi-

cult, or resent, working within prescribed administrative systems and procedures. The

academic staff may well feel that they can only work effectively within an organic

structure, and tend to see non-teaching staff as bureaucratic and resistant to novel or

different ideas. Universities may also tend to be more mechanistic at top management

level with an apparent proliferation of committees and sub-committees, because of

their dealings with, for example, government bodies and other external agencies.

The distinction between mechanistic and organic structures is often most pronounced

between ‘production’ and ‘service’ functions of an organisation. An example of a hybrid

organisation from the private sector could be a large hotel. Here the work tasks and oper-

ations of the kitchen (the production element) suggest that a more mechanistic structure

might be appropriate. Other departments, more concerned with a service element, such

as front office reception, may work better with a more organic structure.

22

The design of an organisation is an exercise in matching structures, systems and style

of management, and the people employed, to the various activities of the organisation.

If there is a mismatch, then problems can arise. Parris gives an example from the tele-

vision programme M*A*S*H (Mobile Army Surgical Hospital):

Activities that are concerned with keeping things going but work in unstable conditions is an

area where mismatching can occur as they contain elements of work that could be made system-

atic and simplified but as a consequence of their need to react quickly to changes to

systematisation could make them less flexible. However, since they are often dealing with com-

plex problems a degree of systematisation is necessary. An example of this would be the 4077th

MASH, where to meet the demands of treating emergencies in battle they need to react quickly.

But to treat complex injuries with complex technology and maintain records, etc. for the future

treatment and other associated administration, a certain level of routine is necessary. Similarly

when the unit is overloaded and necessary medical supplies are not available, considerable

‘negotiation’ and ‘dealing’ with other units etc. is undertaken. The organisation that has evolved

is a sort of Task Culture where everyone works as a team to process the work with easy working

relationships, etc., but it does have role elements in the efficiency with which paperwork is

processed. It has power culture elements for … [the Company Clerk] to negotiate and bargain

with other units and the unit commander has to use personal intervention to keep the unit going

and protect it from the rest of the organisation in which it exists.

The problems of imposing an inappropriate organisational design exists in the shape of [those

who] represent the dominant role organisation in which the unit exists. Their attempts to impose

military rules and procedures and impose the formal rank in the unit are seen as highly inappro-

priate, often farcical.

23

Lawrence and Lorsch undertook a study of six firms in the plastics industry followed by

a further study of two firms in the container industry and two firms in the consumer

food industry.

24

They attempted to extend the work of Burns and Stalker and examined

not only the overall structure, but also the way in which specific departments were

organised to meet different aspects of the firm’s external environment.

644

PART 6 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURES

Matching

structures,

systems and

styles of

management

THE LAWRENCE AND LORSCH STUDY