Mullins L.J. Management and organisational behaviour, Seventh edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Staff relationships arise from the appointment of personal assistants to senior members

of staff. Persons in a staff position normally have little or no direct authority in their

own right but act as an extension of their superior and exercise only ‘representative’

authority. They often act in a ‘gatekeeper’ role. There is no formal relationship between

the personal assistant and other staff except where delegated authority and responsibil-

ity have been given for some specific activity. In practice, however, personal assistants

often do have some influence over other staff, especially those in the same department

or grouping. This may be partially because of the close relationship between the per-

sonal assistant and the superior, and partially dependent upon the knowledge and

experience of the assistant, and the strength of the assistant’s own personality.

Lateral relationships exist between individuals in different departments or sections, espe-

cially individuals on the same level. These lateral relationships are based on

contact and consultation and are necessary to maintain co-ordination and effective organi-

sational performance. Lateral relationships may be specified formally but in practice they

depend upon the co-operation of staff and in effect are a type of informal relationship.

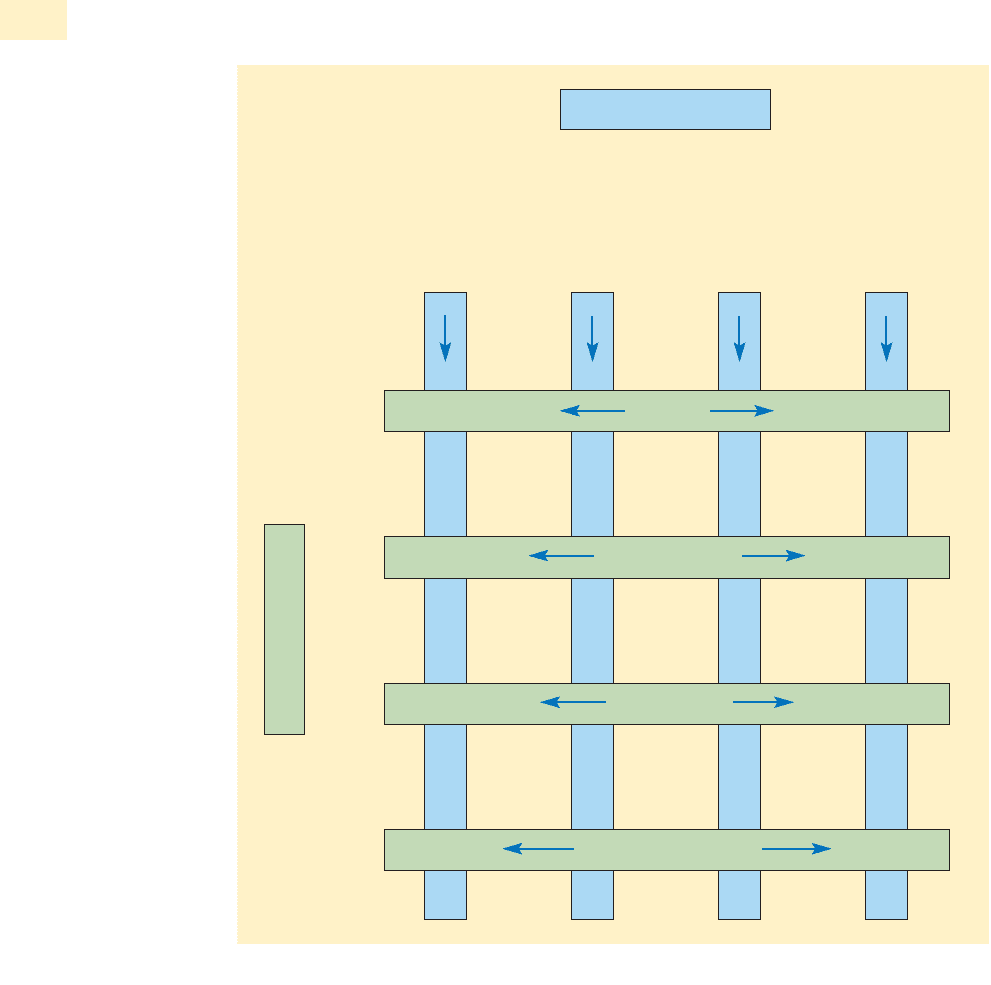

As organisations develop in size and work becomes more complex, the range of activi-

ties and functions undertaken increases. People with specialist knowledge have to be

integrated into the managerial structure. Line and staff organisation is concerned with

different functions which are to be undertaken. It provides a means of making full use

of specialists while maintaining the concept of line authority. It creates a type of infor-

mal matrix structure (see Figure 15.10).

Line organisation relates to those functions concerned with specific responsibility for

achieving the objectives of the organisation and to those people in the direct chain of

command. Staff organisation relates to the provision of specialist and support functions

for the line organisation and creates an advisory relationship. This is in keeping with

the idea of task and element functions discussed earlier. Again, confusion can arise

from conflicting definitions of terminology. In the line and staff form of organisation,

the individual authority relationship defined previously as ‘functional’ now becomes

part of the actual structure under the heading of staff relationships.

The concept of line and staff relations presents a number of difficulties. With the

increasing complexity of organisations and the rise of specialist services it becomes

harder to distinguish clearly between what is directly essential to the operation of the

organisation, and what might be regarded only as an auxiliary function. The distinc-

tion between a line manager and a staff manager is not absolute. There may be a fine

division between offering professional advice and the giving of instructions. Friction

inevitably seems to occur between line and staff managers. Neither side may fully

understand or appreciate the purpose and role of the other. Staff managers are often

CHAPTER 15 ORGANISATION STRUCTURE AND DESIGN

615

Staff

relationships

In business and governmental agencies, from doctors’ offices to licensing and regulatory

boards, one may come face to face with people who have established themselves as gate-

keeper to the boss. Gatekeepers aspire to and are rewarded with various titles, like

administrative assistant, office manager or special assistant to such-and-such. But the

essential role is usually that of secretary to the boss … Aspiring gatekeepers typically evoke

polarised reactions among the office staff … Peers, unlike the boss, quickly recognise the

individual’s lack of integrity and willingness to step on all toes en route to the position of

guardian and the gate.

47

Lateral

relationships

LINE AND STAFF ORGANISATION

Difficulties

with line and

staff relations

criticised for unnecessary interference in the work of the line manager and for being

out of touch with practical realities. Line managers may feel that the staff managers

have an easier and less demanding job because they have no direct responsibility for

producing a product or providing a service for the customer, and are free from day-to-

day operational problems.

Staff managers may feel that their own difficulties and work problems are not appre-

ciated fully by the line manager. Staff managers often complain about resistance to

their attempts to provide assistance and co-ordination, and the unnecessary demands

for departmental independence by line managers. A major source of difficulty is to per-

suade line managers to accept, and act upon, the advice and recommendations which

are offered. The line and staff relationship can also give rise to problems of ‘role incon-

gruence’, discussed in Chapter 13.

616

PART 6 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURES

LINE ORGANISATION

Specific responsibility for all activities within one department.

Direct authority relationship through the hierarchical chain of

command. For example:

Specialist and support services for a common activity throughout

all departments. Advisory relationship with line managers and

their staff. For example:

Research and

development

manager

Production

manager

Marketing

manager

Finance

manager

Personnel

Computer services

Public relations

Management accounting

STAFF ORGANISATION

Figure 15.10 Representation of line and staff organisation

Clutterbuck suggests that a common feature of commercial life is staff departments,

such as human resources and information technology, that have poor reputations

with line managers. Even where line managers are clear what they want staff depart-

ments to do, they are rarely credited with initiative or much relevance to business

objectives. In order to raise their profile, their perceived value and their contribution

to the organisation there are a number of critical activities in the internal marketing

of staff departments:

■ understanding and responding effectively to the needs of internal customers;

■ linking all the department’s activities closely with the strategic objectives of the

business;

■ developing excellent communications and relationships with internal customers;

■ ensuring internal customers’ expectations are realistic; and

■ continuously improving professionalism and capability in line with internal

customers’ needs.

48

Greater awareness of the importance of service delivery, total quality management and

the continual search for competitive advantage has resulted in the concept of an inver-

sion of the traditional hierarchical structure with customers at the summit and top

management at the base. This will be accompanied by the devolution of power and dele-

gation to the empowered, self-managing workers near the top of the inverted pyramid.

49

In inverted organizations the line hierarchy becomes a support structure. The function of line man-

agers becomes bottleneck breaking, culture development, consulting on request, expediting

resource movements and providing service economies of scale. Generally, what was line manage-

ment now performs essentially staff activities. The inverted organization poses certain unique

challenges. The apparent loss of formal authority can be very traumatic for former line managers.

50

The division of work and methods of grouping described earlier tend to be relatively

permanent forms of structure. With the growth in newer, complex and technologically

advanced systems it has become necessary for organisations to adapt traditional struc-

tures in order to provide greater integration of a wide range of functional activities.

Attention has been given, therefore, to the creation of groupings based on project

teams and matrix organisation. Members of staff from different departments or sec-

tions are assigned to the team for the duration of a particular project.

A project team may be set up as a separate unit on a temporary basis for the attainment

of a particular task. When this task is completed the project team is disbanded or mem-

bers of the unit are reassigned to a new task. Project teams may be used for people

working together on a common task or to co-ordinate work on a specific project such as

the design and development, production and testing of a new product; or the design

and implementation of a new system or procedure. For example, project teams have

been used in many military systems, aeronautics and space programmes. A project team

is more likely to be effective when it has a clear objective, a well-defined task, and a defi-

nite end-result to be achieved, and the composition of the team is chosen with care.

According to Mann, project-based working is as old as the pyramids but for increas-

ing numbers of organisations it is very much the new way to do things. ‘In today’s

CHAPTER 15 ORGANISATION STRUCTURE AND DESIGN

617

Internal

marketing

of staff

departments

THE INVERTED ORGANISATION

PROJECT TEAMS AND MATRIX ORGANISATION

Project teams

leaner and meaner organisational set-up it seems that everything is a project and every-

one a project worker.’ Mann suggests two main drivers bringing about this change in

the way work is managed. Firstly, organisations have been stripped down to the core

and resources are limited. Secondly, every area of the business has to contribute and be

accountable as a cost centre. To be effective, projects require clarity at the outset, skills

development, a supportive culture, managing communications and maintaining good

working relationships.

51

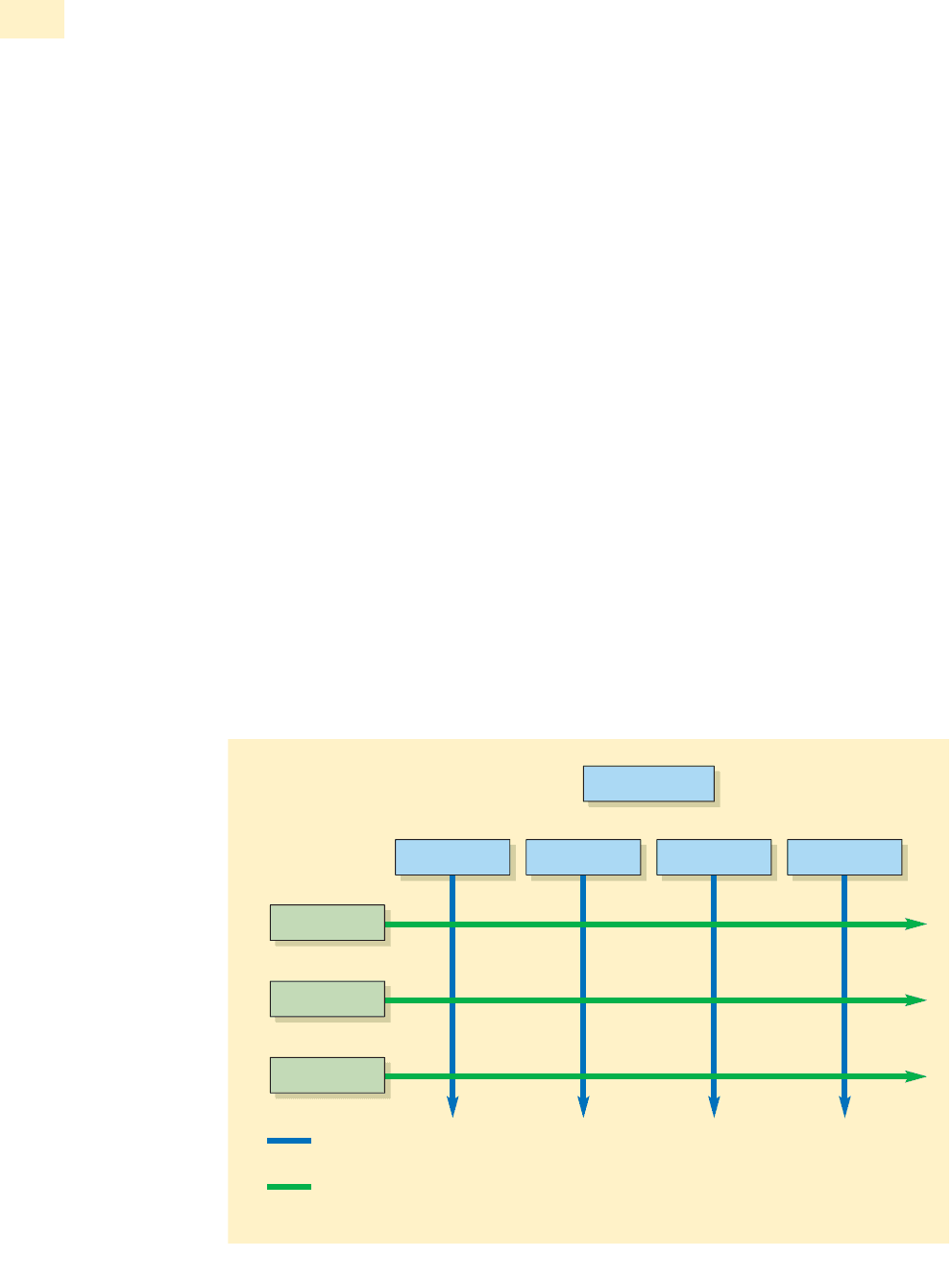

The matrix organisation

The matrix organisation is a combination of:

1 functional departments which provide a stable base for specialised activities and a

permanent location for members of staff; and

2 units that integrate various activities of different functional departments on a pro-

ject team, product, programme, geographical or systems basis. As an example, ICI is

organised on matrix lines, by territory, function and business.

A matrix structure might be adopted in a university or college, for example, with group-

ing both by common subject specialism, and by association with particular courses or

programmes of study. The matrix organisation therefore establishes a grid, or matrix,

with a two-way flow of authority and responsibility (see Figure 15.11). Within the func-

tional departments authority and responsibility flow vertically down the line, but the

authority and responsibility of the ‘project’ manager (or course programme manager)

flow horizontally across the organisation structure.

A matrix design might be adopted in the following circumstances.

1 More than one critical orientation to the operations of the organisation. For

example, an insurance company has to respond simultaneously to both functional

differentiation (such as life, fire, marine, motor) and to different geographical areas.

618

PART 6 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURES

Economics Accounting Management Behavioural

Head of Faculty

SUBJECT SPECIALISMS

COURSE PROGRAMMES

BSc degree

MBA degree

BA degree

Line authority exercised by head of department/section over staff through direct chain

of command

Project authority exercised over selected staff assigned to the course programme from

departments as appropriate

Figure 15.11 Outline of a matrix structure in a university

2 A need to process simultaneously large amounts of information. For example, a

local authority social services department seeking help for an individual will need to

know where to go for help from outside agencies (such as police, priest, community

relations officer) and at the same time whom to contact from internal resources

within the organisation (such as the appropriate social worker, health visitor or

housing officer).

3 The need for sharing of resources. This could only be justified on a total organisa-

tional basis such as the occasional or part-time use by individual departments of

specialist staff or services.

Developing an effective matrix organisation, however, takes time, and a willingness to

learn new roles and behaviour; this means that matrix structures are often difficult for

management to implement effectively.

52

Matrix organisation offers the advantages of flexibility; greater security and control of

project information; and opportunities for staff development. There are, however, a

number of potential difficulties and problem areas.

■ There may be a limited number of staff reporting directly to the project manager

with extra staff assigned as required by departmental managers. This may result in a

feeling of ambiguity. Staff may be reluctant to accept constant change and prefer the

organisational stability from membership of their own functional grouping.

■ Matrix organisation can result in a more complex structure. By using two methods of

grouping it sacrifices the unity of command and can cause problems of co-ordination.

■ There may be a problem of defining the extent of the project manager’s authority

over staff from other departments and of gaining the support of other functional

managers.

■ Functional groups may tend to neglect their normal duties and responsibilities.

An underlying difficulty with matrix structures is that of divided loyalties and role con-

flict with individuals reporting simultaneously to two managers; this highlights the

importance of effective teamwork. According to Bartlett and Ghoshal, matrix structures

have proved all but unmanageable. Dual reporting leads to conflict and confusion; the

proliferation of channels of communication creates informational log-jams; and overlap-

ping responsibilities result in a loss of accountability.

53

And Senior makes the point that:

Matrix structures rely heavily on teamwork for their success, with managers needing high-level

behavioural and people management skills. The focus is on solving problems through team

action … This type of organisational arrangement, therefore, requires a culture of co-operation,

with supportive training programmes to help staff develop their teamworking and conflict-

resolution skills.

54

It is not easy to describe, in a positive manner, what constitutes a ‘good’ or effective

organisation structure although, clearly, attention should be given to the design princi-

ples discussed above. However, the negative effects of a poorly designed structure can be

identified more easily. In his discussion on the principles of organisation and coordina-

tion, Urwick suggests that ‘Lack of design is Illogical, Cruel, Wasteful and Inefficient’.

55

■ It is illogical because in good social practice, as in good engineering practice, design

should come first. No member of the organisation should be appointed to a senior

position without identification of the responsibilities and relationships attached to

that position and its role within the social pattern of the organisation.

CHAPTER 15 ORGANISATION STRUCTURE AND DESIGN

619

Difficulties

with matrix

structures

EFFECTS OF A DEFICIENT ORGANISATION STRUCTURE

■ It is cruel because it is the individual members of the organisation who suffer most

from lack of design. If members are appointed to the organisation without a clear

definition of their duties or the qualifications required to perform those duties, it is

these members who are likely to be blamed for poor results which do not match the

vague ideas of what was expected of them.

■ It is wasteful because if jobs are not put together along the lines of functional spe-

cialisation then new members of the organisation cannot be training effectively to

take over these jobs. If jobs have to be fitted to members of the organisation, rather

than members of the organisation fitted to jobs, then every new member has to be

trained in such a way so as to aim to replace the special, personal experience of the

previous job incumbent. Where both the requirements of the job and the member

of the organisation are unknown quantities this is likely to lead to indecision and

much time wasted in ineffective discussion.

■ It is inefficient because if the organisation is not founded on principles, managers

are forced to fall back on personalities. Unless there are clearly established princi-

ples, which are understood by everyone in the organisation, managers will start

‘playing politics’ in matters of promotion and similar issues.

Urwick lays emphasis on the technical planning of the organisation and the impor-

tance of determining and laying out structure before giving any thought to the

individual members of the organisation. Although Urwick acknowledges that the per-

sonal touch is important, and part of the obvious duty of the manager, it is not a

substitute for the need for definite planning of the structure.

In short, a very large proportion of the friction and confusion in current society, with its manifest

consequences in human suffering, may be traced back directly to faulty organisation in the struc-

tural sense.

56

Urwick’s emphasis on the logical design of organisation structure rather than the

development around the personalities of its members is typical of the classical

approach to organisation and management. Despite this rather narrow view, more

recent writers have drawn similar conclusions as to the consequences of badly designed

structure.

For example, Child points out that:

There are a number of problems which so often mark the struggling organization and which even

at the best of times are dangers that have to be looked for. These are low motivation and morale,

late and inappropriate decisions, conflict and lack of co-ordination, rising costs and a generally

poor response to new opportunities and external change. Structural deficiencies can play a part

in exacerbating all these problems.

57

Child then goes on to explain the consequences of structural deficiencies.

■ Low motivation and morale may result from: apparently inconsistent and arbitrary

decisions; insufficient delegation of decision-making; lack of clarity in job definition

and assessment of performance; competing pressures from different parts of

the organisation; and managers and supervisors overloaded through inadequate

support systems.

■ Late and inappropriate decisions may result from: lack of relevant, timely infor-

mation to the right people; poor co-ordination of decision-makers in different units;

overloading of decision-makers due to insufficient delegation; and inadequate pro-

cedures for revaluation of past decisions.

■ Conflict and lack of co-ordination may result from: conflicting goals and people

working at cross-purposes because of lack of clarity on objectives and priorities; fail-

ure to bring people together into teams or through lack of liaison; and breakdown

between planning and actual operational work.

620

PART 6 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURES

Consequences

of badly

designed

structure

■ Poor response to new opportunities and external change may result from: failure

to establish specialist jobs concerned with forecasting environmental change; failure

to give adequate attention to innovation and planning of change as main manage-

ment activities; inadequate co-ordination between identification of market changes

and research into possible technological solutions.

■ Rising costs may result from: a long hierarchy of authority with a high proportion

of senior positions; an excess of administrative work at the expense of productive

work; and the presence of some, or all, of the other organisational problems.

Shortcomings in structure may also provide greater opportunities for the illicit activi-

ties of staff. For example the collapse of Britain’s oldest merchant bank, Barings, and

the activities of ‘rogue trader’ Nick Leeson were made more straightforward by the

major reorganisation and expanded structure of the Barings empire.

58

The structure of an organisation is usually depicted in the form of an organisation

chart. This will show, at a given moment in time, how work is divided and the group-

ing together of activities, the levels of authority and formal organisational

relationships. The organisation chart provides a pictorial representation of the overall

shape and structural framework of an organisation. Some charts are very sketchy and

give only a minimum amount of information. Other charts give varying amounts of

additional detail such as an indication of the broad nature of duties and responsibili-

ties of the various units.

Charts are usually displayed in a traditional, vertical form such as those already

depicted in Figures 15.8 and 15.9 above. They can, however, be displayed either hori-

zontally with the information reading from left to right, or concentrically with top

management at the centre. The main advantage of both the horizontal and the con-

centric organisation charts is that they tend to reduce the indication of superior or

subordinate status. They also offer the practical advantage of more space on the outer

margin. In addition, the concentric chart may help to depict the organisation more as

a unified whole. Organisation charts are useful in explaining the outline structure of

an organisation. They may be used as a basis for the analysis and review of structure,

for training and management succession, and for formulating changes. The chart may

indicate apparent weaknesses in structure such as, for example:

■ too wide a span of control;

■ overlapping areas of authority;

■ lack of unity of command;

■ too long a chain of command;

■ unclear reporting relationships and/or lines of communication;

■ unstaffed functions.

There are, however, a number of limitations with traditional organisation charts. They

depict only a static view of the organisation, and show how it looks and what the struc-

ture should be. Charts do not show the comparative authority and responsibility of

positions on the same level, or lateral contacts and informal relations. Neither do charts

show the extent of personal delegation from superior to subordinates, or the precise rela-

tionships between line and staff positions. Organisation charts can become out of date

quickly and are often slow to be amended to reflect changes in the actual structure.

Despite these limitations, the organisation chart can be a valuable and convenient

way of illustrating the framework of structure – provided the chart is drawn up in a

comprehensible form. There is always the question of what the chart does not show

CHAPTER 15 ORGANISATION STRUCTURE AND DESIGN

621

ORGANISATION CHARTS

Limitations of

organisation

charts

and what the observer interprets from it. There are a number of conventions in draw-

ing up organisation charts. It is not the purpose here to go into specific details, but it is

important to remember that the chart should always give:

■ the date when it was drawn up;

■ the name of the organisation, branch or department (as appropriate) to which

it refers;

■ whether it is an existing or proposed structure;

■ the extent of coverage, for example if it refers to the management structure only, or

if it excludes servicing departments;

■ a reference to identify the person who drew up the chart.

While acknowledging that organisation charts have some uses, Townsend likens them

to ‘rigor mortis’ and advises that they should be drawn in pencil.

Never formalize, print and circulate them. Good organizations are living bodies that grow new

muscles to meet challenges. A chart demoralizes people. Nobody thinks of himself as below

other people. And in a good company he isn’t. Yet on paper there it is … In the best organizations

people see themselves working in a circle as if around one table.

59

It is clear, then, that it is essential to give full attention to the structure and design of

an organisation. However, this is not always an easy task.

Designing structures which achieve a balance between co-operation and competition, which

combine team behaviours and individual motivation, is one of the hardest parts of building

organisations – or designing economic systems.

60

In analysing the effectiveness of structure, consideration should be given to both the

formal and technological requirements and principles of design; and to social factors,

and the needs and demands of the human part of the organisation. Structure should be

designed so as to maintain the balance of the socio-technical system, and to encourage

the willing participation of members and effective organisational performance.

An organisation can be separated into two partsorstructures which can then be examined. One

section is a definable structure that will be present in every company, the other is the structure

caused by human intervention. The latter provides the company with its distinctive appearance,

and may be regarded as the manager’s particular response to the design requirements of organ-

ised behaviour. Essentially the effectiveness of an organisation depends on how accurately

human design matches the structure of organised behaviour.

61

The structure or charts do not describe what really happens in work organisations. To

conclude our discussion we need to remind ourselves of the ‘realities’ of organisational

behaviour and of points made in previous chapters. Rarely do all members of an organi-

sation behave collectively in such a way as to represent the behaviour of the

organisation as a whole. In practice, we are referring to the behaviour of individuals, or

sections or groups of people, within the organisation. Human behaviour is capricious

and prescriptive methods or principles cannot be applied with reliability. Individuals

differ and people bring their own perceptions, feelings and attitudes towards the organi-

sation, styles of management and their duties and responsibilities. The behaviour of

people cannot be studied in isolation and we need to understand interrelationships

with other variables which comprise the total organisation, including the social context

of the work organisation and the importance of the informal organisation. The behav-

iour and actions of people at work will also be influenced by a complexity of

motivations, needs and expectations.

622

PART 6 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURES

STRUCTURE AND ORGANISATIONAL BEHAVIOUR

‘Realities’ of

organisational

behaviour

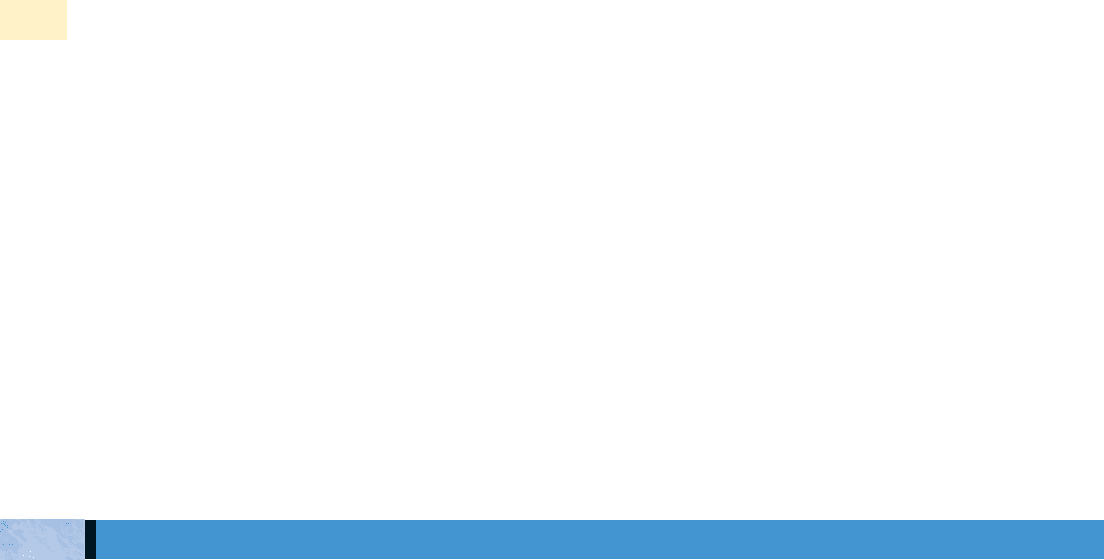

Gray and Starke provide a humorous but perhaps realistic illustration of how an

organisation actually works (see Figure 15.12).

62

Heller also refers to:

the gap between the aims of big company organizations and what actually happens.

Organizational form and organizational behaviour are not one and the same thing.

63

The changing world of organisations and management

Birchall refers to the changing world of organisations and its impact on management. As

a consequence of factors such as global competition, the convergence of information and

communications technology, the emergence of the digital economy, recession in most

Western economies, the emergence of customer power and changing political philoso-

phy, much of the work undertaken by middle management no longer requires the

considerable layers of management. Tasks that used to take up a great deal of manage-

ment time in hierarchical structures are now possible with minimal supervision or

intervention. Much of the organisation’s work is carried out in projects. Many managers

will find themselves managing people who spend much of their time outside the office.

There is a strong move towards the use of consultants. Managers will need to be familiar

with electronic networks, the operation of dispersed teams and virtual organisations.

64

Birchall draws attention to management as no longer the sole prerogative of an elite

group called managers. The functions of management are being much more widely

shared within an enterprise and possibly the greatest potential in managing complex

organisations lies in releasing the organisation’s creative capabilities. A similar point is

CHAPTER 15 ORGANISATION STRUCTURE AND DESIGN

623

Figure 15.12 How the organisation should be compared with how it actually works

(Source: Gray. J. L. and Starke. F. A. Organisational Behaviour: Concepts and Applications, Fourth edition. Merrill Publishing Company, an

imprint of Macmillan Publishing Company (1988) p. 431. Reproduced with permission from Pearson Education, Inc., Upper Saddle River, NJ.)

made by Cloke and Goldsmith who maintain that management is an idea whose time is

up and the days of military command structures are over.

Rather than building fixed structures with layers of middle management, many innovative organ-

isations function as matrixed webs of association, networks, and fast-forming high-performance

teams … The most significant trends we see in the theory and history of management are the

decline of the hierarchical, bureaucratic, autocratic management and the expansion of collabora-

tive self-management and organisational democracy.

65

■ Structure provides the framework of an organisation and makes possible the appli-

cation of the process of management. The structure of an organisation affects not only

productivity and economic efficiency but also the morale and job satisfaction of its

members. The overall effectiveness of the organisation will be influenced both by

sound structural design, and by the behaviour of people who work within the struc-

ture. Attention must be given to maintaining the socio-technical system and to

integrating the structural and technological requirements of the organisation, and the

needs and demands of the human part of the organisation.

■ Some structure is necessary to make possible the effective performance of key activ-

ities and to support the efforts of staff. Organisations are layered and within the

hierarchical structure there are three broad, interrelated levels: technical, managerial

and community. The changing nature of the work organisation has led to discussion

624

PART 6 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURES

CRITICAL REFLECTIONS

‘Organisations are a form of social stratification.’

‘Yes, I suppose they are.’

‘Advancement up the organisation can reasonably be expected to be seen as a reward for

hard work, an indication of achievement and obtained by reason of merit.’

‘I hear what you say but this seems to imply that those people at lower levels of the structure

do not work hard, have failed to achieve and lack merit. Can this be right?’

What are your own views?

Probably the most immediate and accessible way to describe any formal organization is to out-

line its structure. For the student of organizations, knowledge of its structure is indispensable as

a first step to understanding the processes which occur within it. When asked to describe their

organization, managers will frequently sketch an organization chart to show how their organiza-

tion ‘works’.

Rosenfeld, R. H. and Wilson, D. C., Managing Organizations: Text, Readings & Cases, Second edition, McGraw-Hill

(1999), p. 255.

How would you depict the chart of your own organisation in order to describe clearly

how the organisation ACTUALLY works?

‘The structure of an organisation is unimportant. What matters is whether individuals do their

jobs well or not.’

Debate.

SYNOPSIS