Mullins L.J. Management and organisational behaviour, Seventh edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Perceptual distortions and inaccuracies may not only affect our perception of the en-

vironment but also affect our perception of people. Although the process of perception

is equally applicable in the perception of objects or people, there is more scope for sub-

jectivity, bias, errors and distortions when we are perceiving others. The focus of the

following section is to examine the perception of people, and to consider the impact

this has on the management and development of people at work.

The principles and examples of perceptual differences discussed above reflect the way

we perceive other people and are the source of many organisational problems. In the

work situation the process of perception and the selection of stimuli can influence a

manager’s relationship with other staff. Some examples might be as follows.

■ Grouping – the way in which a manager may think of a number of staff: for ex-

ample, either working in close proximity; or with some common feature such as all

clerical workers, all management trainees or all black workers; as a homogeneous

group rather than a collection of individuals each with his or her own separate iden-

tity and characteristics;

■ Figure and ground – a manager may notice a new recruit and set him/herself apart

from the group because of particular characteristics such as appearance or physical

features.

■ Closure – the degree to which unanimity is perceived, and decisions made or action

taken in the belief that there is full agreement with staff when, in fact, a number of

staff may be opposed to the decision or action.

A manager’s perception of the workforce will influence attitudes in dealing with people

and the style of managerial behaviour adopted. The way in which managers approach

the performance of their jobs and the behaviour they display towards subordinate staff

are likely to be conditioned by predispositions about people, human nature and work.

An example of this is the style of management adopted on the basis of McGregor’s

Theory X and Theory Y suppositions, which is discussed in Chapter 7. In making

judgements about other people it is important to try and perceive their underlying

intent and motivation, not just the resultant behaviour or actions.

The perception of people’s performance can be affected by the organisation of stim-

uli. In employment interviews, for example, interviewers are susceptible to contrast

effects and the perception of a candidate is influenced by the rating given to immedi-

ately preceding candidates. Average candidates may be rated highly if they follow

people with low qualifications, but rated lower when following people with higher

qualifications.

13

The dynamics of interpersonal perception

The dynamics of person perception cannot be overestimated. Unlike the perception of

an object which just exists, another individual will react to you and be affected by your

behaviour. This interaction is illustrated in the following quotation:

You are a pain in the neck and to stop you giving me a pain in the neck I protect my neck by tight-

ening my neck muscles, which gives me the pain in the neck you are.

14

CHAPTER 11 THE PROCESS OF PERCEPTION

445

Person

perception

PERCEIVING OTHER PEOPLE

The interaction of individuals thus provides an additional layer of interpretation and

complexity. The cue which we may attend to, the expectation we may have, the

assumptions we may make, the response pattern that occurs, leave more scope for

errors and distortions. We are not only perceiving the stimulus (that is, the other

person) but we are also processing their reactions to us at the same time that they are

processing our reactions to them.

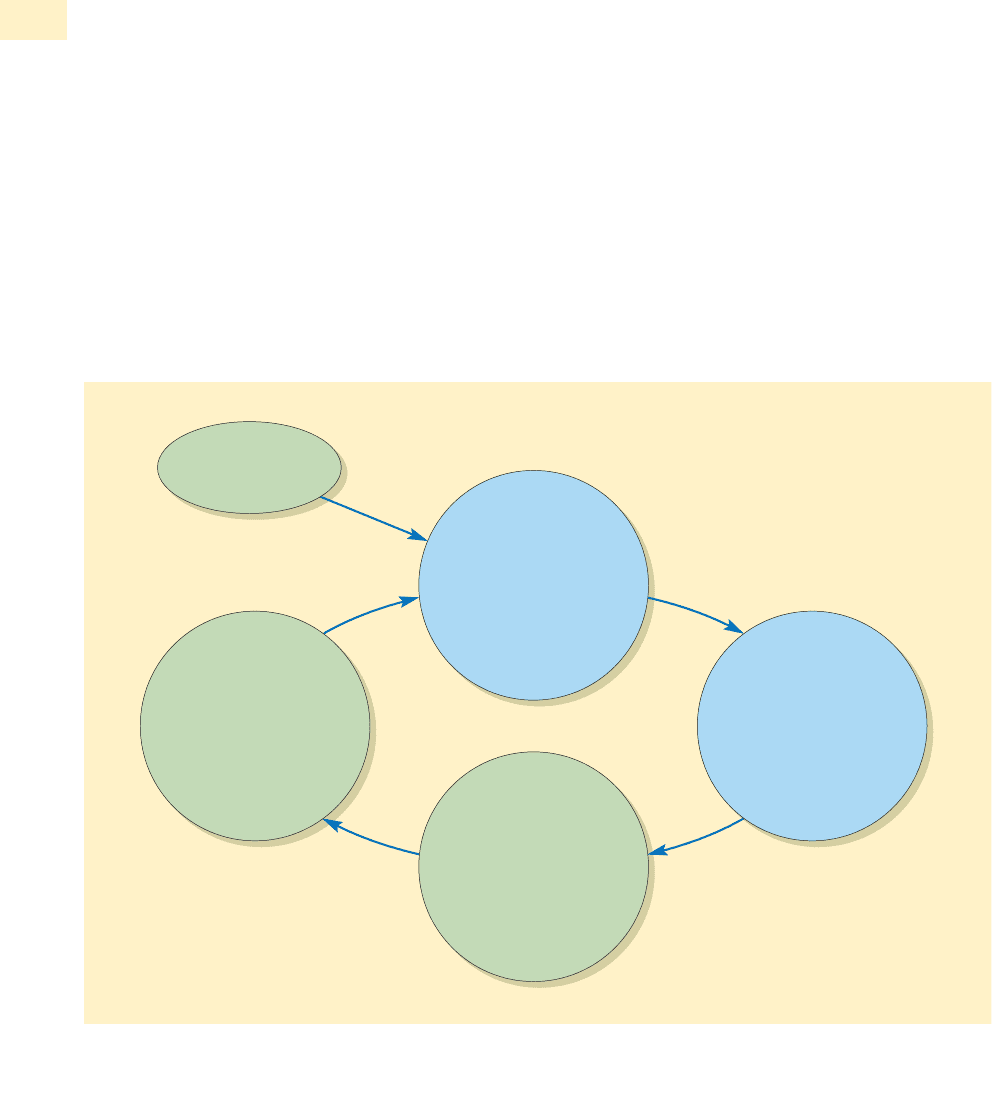

Thus person perception differs from the perception of objects because:

■ it is a continually dynamic and changing process; and

■ the perceiver is a part of this process who will influence and be influenced by the

other people in the situation.

(See Figure 11.12.)

15

Person perception will also be affected by the setting, and the environment may play a

critical part in establishing rapport. For example, next time you are involved in a formal

meeting consider the following factors which will all influence the perceptual process.

PART 4 THE INDIVIDUAL

446

Person B interprets

A’s speech,

movement and

gestures in order to

understand A’s

motives, emotions,

assumptions,

attitudes, intentions,

abilities.

A responds in

speech,

movement,

gesture, etc.

A interprets B’s

speech, movement

and gestures in

order to understand

B’s motives,

emotions,

assumptions,

attitudes, intentions,

abilities.

B responds in

speech,

movement,

gesture, etc.

Person A speaks,

moves, gestures,

etc.

Figure 11.12 Cycle of perception and behaviour

Reproduced with permission form Maureen Guirdham, Interactive Behaviour at Work, Third edition, Financial Times Prentice Hall (2002), p. 162, with permission from

Pearson Education Ltd.

Setting and

environment

It is difficult to consider the process of interpersonal perception without commenting

on how people communicate. Communication and perception are inextricably bound.

How we communicate to our colleagues, boss, subordinates, friends and partners will

depend on our perception of them, on our ‘history’ with them, on their emotional

state, etc. We may misjudge them and regard our communication as unsuccessful, but

unless we have some feedback from the other party we may never know whether what

we have said, or done, was received in the way it was intended. Feedback is a vital

ingredient of the communication process. The feedback may reaffirm our perceptions

of the person or it may force us to review our perceptions. In our dealings with more

CHAPTER 11 THE PROCESS OF PERCEPTION

447

Why? Purpose of and motives Likely to be an important event for the

for meeting particpant, may be a catalyst for promotion

and may signal new and relevant

development opportunities.

Chance to be visible and demonstrate skills

and abilities.

Opportunity to network with other managers.

Thus high emotional cost to participant

Who? Status/role/age/ How participant prepares for the event will

gender/ethnic group/ be influenced by factors listed across and

appearance/personality/ previous history and encounters of all parties

interests/attitudes

When? Time, date of meeting The timing of the event might be particularly

affected by events outside of the workplace.

So if the participant has dependants or

responsibilities the timing of this event may

become significant. If the participant is asked

to attend in the middle of a religious festival

than again the relevance of time is critical.

Where? Environment/culture Organisations will often stage development

events away from the ‘normal’ workplace in

an attempt to bring about objectivity and

neutrality.

How the event is staged, the amount of

structure and formality, how feedback is

given, the demonstration of power and

control will be evidence of the culture of the

organisation.

How? Past experience The experience of the development event will

Rapport in part be influenced by the expectations of

the participant. If this is the second

development centre then experiences of the

first will colour the perceptions, if this is the

first centre then the participant may be

influenced by previous experiences of similar

events (selection event) or by stories from

previous attendees.

Perception and

communication

For example, attending an in-house development centre:

senior staff the process of communication can be of special significance including non-

verbal communication, posture and tone.

16

(The importance of body language is

discussed later in this chapter.)

Transactional analysis (or TA) is one of the most popular ways of explaining the dynam-

ics of interpersonal communication. Originally developed by Eric Berne, it is now a

theory which encompasses personality, perception and communication. Although

Berne used it initially as a method of psychotherapy, it has been convincingly used by

organisations as a training and development programme.

20

TA has two basic underlying assumptions:

■

All the events and feelings that we have ever experienced are stored within us and can

be replayed, so we can re-experience the events and the feelings of all our past years.

PART 4 THE INDIVIDUAL

448

TRANSACTIONAL ANALYSIS

Neuro-linguistic programming (NLP)

John Grinder and Richard Bandler developed

neuro-linguistic programming

in the

1970s.

17

The name originates from the three disciplines which all have a part to play

when people are communicating with others: neurology, language and programming.

■ Neurology – the processes linking body and mind;

■

Linguistics – the study of words and how these are understood and communicated;

■ Programming – refers to behaviours and strategies used by individuals.

Originally Grinder and Bandler studied notable therapists at work with their

clients. The aim was to identify ‘rules’ or models that could be used by other thera-

pists to help them improve their performance. The focus was on one-to-one

communication and self-management. The application of NLP shifted from ther-

apy situations to work organisations with clear messages for communicating and

managing others.

NLP emphasises the significance of the perceptual process and the way in which

information is subjectively filtered and interpreted. These interpretations are influ-

enced by others and the world in which we live. Gradually individuals learn to

respond and their reactions and strategies become programmed, locked in, automatic.

At its heart NLP concerns awareness and change. Initially knowing and monitor-

ing one’s own behaviour is fundamental to the process and being able to

consciously choose different reactions. Selecting from a range of verbal and non-

verbal behaviours ensures control happens and changes ‘automatic’ reactions into

consciously chosen programmes.

Many different approaches and techniques are incorporated into NLP. Some

concern mirroring and matching the micro skills of communication in terms of

body movements, breathing patterns or voice tempo. Others concern the positive

thinking required in goal-setting ‘outcome thinking’ and the personal resources

required in its achievement.

NLP has passionate devotees (see for instance http://www.nlpu.com) and consider-

able hype, for instance one practitioner claims to ‘skyrocket your communication

skills’. It claims NLP to be different: ‘Feel what it is like; see yourself and hear yourself

actually speaking, as you interact and communicate perfectly.’

18

Some of the ideas of NLP have been incorporated in other bodies of knowledge

on communication. So for example McCann bases his communication work on

the findings of Grinder and Bandler to produce a technique called psychoverbal

communication.

19

■ Personality is made of three ego states which are revealed in distinct ways of behav-

ing. The ego states manifest themselves in gesture, tone of voice and action, almost

as if they are different people within us.

Berne identified and labelled the ego states as follows:

■ Child ego state – behaviour which demonstrates the feelings we remember as a

child. This state may be associated with having fun, playing, impulsiveness, rebel-

liousness, spontaneous behaviour and emotional responses.

■ Adult ego state – behaviour which concerns our thought processes and the process-

ing of facts and information. In this state we may be objective, rational, reasonable –

seeking information and receiving facts.

■ Parent ego state – behaviour which concerns the attitudes, feelings and behaviour

incorporated from external sources, primarily our parents. This state refers to feel-

ings about right and wrong and how to care for other people.

He claimed that the three ego states were universal, but the content of the ego states

would be unique to each person. We may be unaware which ego state we are operating

in and may shift from one ego state to another. All people are said to behave in each of

these states at different times. The three ego states exist simultaneously within each

individual although at any particular time any one state many dominate the other two.

We all have a preferred ego state which we may revert to: some individuals may con-

tinually advise and criticise others (the constant Parents); some may analyse, live only

with facts, and distrust feelings (the constant Adult); some operate with strong feelings

all the time, consumed with anger, or constantly clowning (the constant Child). Berne

emphasised that the states should not be judged as superior or inferior but as different.

Analysis of ego states may reveal why communication breaks down or why individuals

may feel manipulated or used.

Berne insists that it is possible to identify the ego state from the words, voice, ges-

tures, and attitude of the person communicating. For example, it would be possible to

discern the ego state of a manager if he/she said the following:

‘Pass me the file on the latest sales figures.’

‘How do you think we could improve our safety record?’

(Adult ego state)

‘Let me help you with that – I can see you are struggling.’

‘Look, this is the way it should be done; how many more times do I have to tell

you...?’

(Parent ego state)

‘Great, it’s Friday. Who’s coming to the pub for a quick half?’

‘That’s a terrific idea – let’s go for it!’

(Child ego state)

A dialogue can be analysed not only in terms of the ego state but also whether the

transaction produced a complementary reaction or a crossed reaction. By comple-

mentary it is meant whether the ego state was an expected and preferred response, so

for instance if we look at the first statement, ‘Pass me the file on the latest sales fig-

ures’, the subordinate could respond: ‘Certainly – I have it here’ (Adult ego state), or

‘Can’t you look for it yourself? I only gave it to you an hour ago’ (Parent ego state).

The first response was complementary whereas the second was a crossed transaction.

Sometimes it may be important to ‘cross’ a transaction. Take the example ‘Let me help

you with that – I can see you are struggling’ (Parent ego state). The manager may have a

habit of always helping in a condescending way, making the subordinate resentful. If

the subordinate meekly accepts the help with a thankful reply this will only reinforce

CHAPTER 11 THE PROCESS OF PERCEPTION

449

Preferred ego

state

the manager’s perception and attitude, whereas if the subordinate were to respond with

‘I can manage perfectly well. Why did you think I was struggling?’, it might encourage

the manager to respond from the Adult ego state and thus move his/her ego position.

Knowledge of TA can be of benefit to employees who are dealing with potentially diffi-

cult situations.

21

In the majority of work situations the Adult–Adult transactions are

likely to be the norm. Where work colleagues perceive and respond by adopting the

Adult ego state, such a transaction is more likely to encourage a rational, problem-

solving approach and reduce the possibility of emotional conflict.

If only the world of work was always of the rational logical kind! Communications

at work as elsewhere are sometimes unclear, confused and can leave the individual

with ‘bad feelings’ and uncertainty. Berne describes a further dysfunctional transaction,

which can occur when a message is sent to two ego states at the same time. For

instance an individual may say ‘I passed that article to you last week, have you read it

yet?’ This appears to be an adult-to-adult transaction and yet the tone of voice, the

facial expressions imply a second ego state is involved. The underlying message says

‘Haven’t you even read that yet … you know how busy I am and yet I had time to read

it!’ The critical parent is addressing the Child ego state. In such ‘ulterior transactions’

the social message is typically Adult to Adult, and the ulterior, psychological message is

directed either Parent–Child or Child–Parent.

Given the incidence of stress in the workplace, analysis of communication may be

one way of understanding such conflict. By focusing on the interactions occurring

within the workplace, TA can aid the understanding of human behaviour. It can help

to improve communication skills by assisting in interpreting a person’s ego state and

which form of state is likely to produce the most appropriate response. This should

lead to an improvement in both customer relations and management–subordinate rela-

tions. TA can be seen therefore as a valuable tool to aid our understanding of social

situations and the games that people play both in and outside work organisations.

TA emphasises the strong links between perception and communication and illus-

trates the way in which they affect each other. However, it does not answer how we

construct our social world in the first place, what we attend to and why, or why we

have positive perceptions about some people and not others. To answer these ques-

tions we can concentrate on the stages of the perceptual process – both selection

and attention, and organisation and judgement – and apply these to the perception

of people.

What information do we select and why? The social situation consists of both verbal

and non-verbal signals. The non-verbal signals include:

■ bodily contact;

■ proximity;

■ orientation;

■ head nods;

■ facial expression;

■ gestures;

■ posture;

■ direction of gaze;

■ dress and appearance;

■ non-verbal aspects of speech.

PART 4 THE INDIVIDUAL

450

Understanding

of human

behaviour

SELECTION AND ATTENTION

Verbal and non-verbal signals are co-ordinated into regular sequences, often without

the awareness of the parties. The mirroring of actions has been researched and is called

‘postural echoing’.

22

There is considerable evidence to indicate that each person is con-

stantly influencing the other, and being influenced.

23

Cook has suggested that in any social encounter there are two kinds of information

which can be distinguished:

■ static information – information which will not change during the encounter: for

example, colour, gender, height and age; and

■ dynamic information – information which is subject to change: for example,

mood, posture, gestures and expression.

24

The meanings we ascribed to these non-verbal signals are rooted in our culture and

early socialisation. Thus it is no surprise that there are significant differences in the

way we perceive such signals. For instance dress codes differ in degrees of formality.

Schneider and Barsoux summarise some interesting cultural differences:

Northern European managers tend to dress more informally than their Latin counterparts. At con-

ferences, it is not unlikely for the Scandinavian managers to be wearing casual clothing, while

their French counterparts are reluctant to remove their ties and jackets. For the Latin managers,

personal style is important, while Anglo and Asian managers do not want to stand out or attract

attention in their dress. French women managers are more likely to be dressed in ways that

Anglo women managers might think inappropriate for the office. The French, in turn, think it

strange that American businesswomen dress in ‘man-like’ business suits (sometimes with run-

ning shoes).

25

In some situations we all attempt to project our attitudes, personality and competence

by paying particular attention to our appearance, and the impact this may have on

others. This has been labelled ‘impression management’

26

and the selection interview

is an obvious illustration. Some information is given more weight than other informa-

tion when an impression is formed. It would seem that there are central traits which

are more important than others in determining our perceptions.

One of these central traits is the degree of warmth or coldness shown by an individ-

ual.

27

The timing of information also seems to be critical in the impressions we form.

For example, information heard first tends to be resistant to later contradictory informa-

tion. In other words, the saying ‘first impression counts’ is supported by research and is

called ‘the primacy effect’.

28

It has also been shown that a negative first impression is

more resistant to change than a positive one.

29

However, if there is a break in time we

are more likely to remember the most recent information – ‘the recency effect’.

There are a number of well-documented problems which arise when perceiving other

people. Many of these problems occur because of our limitations in selecting and

attending to information. This selectivity may occur because:

■ we already know what we are looking for and are therefore ‘set’ to receive only the

information which confirms our initial thoughts; or

■ previous training and experience have led us to short-cut and only see a certain

range of behaviours; or

■ we may group features together and make assumptions about their similarities.

The Gestalt principles apply equally well to the perception of people as to the perception

of objects. Thus we can see, for example, that if people live in the same geographical

area, assumptions may be made about not only their wealth and type of accommodation

but also their attitudes, their political views and even their type of personality.

CHAPTER 11 THE PROCESS OF PERCEPTION

451

Impression

management

Dealings with

other people

PART 4 THE INDIVIDUAL

452

The ways in which we organise and make judgements about what we have perceived is to

a large extent based on our previous experiences and learning. It is also important at this

point to be aware of the inferences and assumptions we make which go beyond the

information given. We may not always be aware of our pre-set assumptions but they will

guide the way in which we interpret the behaviour of others. There has been much

research into the impact of implicit personality theory.

30

In the same way that we make

assumptions about the world of objects, and go beyond the information provided, we

also make critical inferences about people’s characteristics and possible likely behaviours.

A manager might well know more about the ‘type of person’ A – a member of staff

who has become or was already a good friend, who is seen in a variety of social situ-

ations and with whom there is a close relationship – than about B – another member

of staff, in the same section as A and undertaking similar duties, but with whom there

is only a formal work relationship and a limited social acquaintance. These differences

in relationship, information and interaction might well influence the manager’s per-

ception if asked, for example, to evaluate the work performance of A and B.

Judgement of other people can also be influenced by perceptions of such stimuli as,

for example:

■ role or status;

■ occupation;

■ physical factors and appearance; and

■ body language.

Physical characteristics and appearance

In a discussion on managing people and management style, Green raises the question

of how managers make judgements on those for whom they are responsible including

positive and negative messages.

In my personal research people have admitted, under pressure, that certain physical characteris-

tics tend to convey a positive or negative message. For example, some people find red hair,

earrings for men, certain scents and odours, someone too tall or too short; a disability; a

member of a particular ethnic group and countless other items as negative … Similarly there will

be positive factors such as appropriate hairstyle or dress for the occasion … which may influence

in a positive way.

31

A person may tend to organise perception of another person in terms of the ‘whole’

mental picture of that person. Perceptual judgement is influenced by reference to

related characteristics associated with the person and the attempt to place that person

in a complete environment. In one example, an unknown visitor was introduced by

the course director to 110 American students, divided into five equal groups.

32

The vis-

itor was described differently to each group as:

1Mr England, a student from Cambridge;

2Mr England, demonstrator in psychology from Cambridge;

3Mr England, lecturer in psychology from Cambridge;

4 Dr England, senior lecturer from Cambridge;

5 Professor England from Cambridge.

After being introduced to each group, the visitor left. Each group of students was then

asked to estimate his height to the nearest half inch. They were also asked to estimate

the height of the course director after he too left the room. The mean estimated height

of the course director, who had the same status for all groups, did not change signifi-

ORGANISATION AND JUDGEMENT

Related

characteristics

cantly among groups. However, the estimated height of the visitor varied with per-

ceived status: as ascribed academic status increased, so did the estimate of height. (See

Table 11.1.)

We have referred previously in this chapter to the particular significance of body lan-

guage and non-verbal communication. This includes inferences drawn from posture,

invasions of personal space, the extent of eye contact, tone of voice or facial expres-

sion. People are the only animals that speak, laugh and weep. Actions are more

cogent than speech, and humans rely heavily on body language to convey their true

feelings and meanings.

33

It is interesting to note how emotions are woven creatively

into email messages. Using keyboard signs in new combinations has led to a new e-

language. For example to signal pleasure :), or unhappiness :–c, or send a rose @>--->

encapsulate feelings as well as words. The growth of this practice has led to an

upsurge of web pages replete with examples.

James suggests that in a sense, we our all experts on body language already and this is

part of the survival instinct.

Even in a ‘safe’ environment like an office or meeting room you will feel a pull on your gaze each time

someone new enters the room. And whether you want to or not, you will start to form opinions about

a person in as little as three seconds. You can try to be fair and objective in your evaluation, but you

will have little choice. This is an area where the subconscious mind bullies the conscious into sub-

mission. Like, dislike, trust, love or lust can all be promoted in as long as it takes to clear your throat.

In fact most of these responses will be based on your perception of how the person looks.

37

CHAPTER 11 THE PROCESS OF PERCEPTION

453

Group Ascribed academic status Average estimated height

1 Student 5' 9.9"

2 Demonstrator 5' 10.14"

3Lecturer 5' 10.9"

4 Senior lecturer 5' 11.6"

5Professor 6' 0.3"

Table 11.1 Estimated height according to ascribed academic status

(Source: Adapted from Wilson, P. R. ‘Perceptual Distortion of Height as a Function of Ascribed Academic Status’, Journal of Social

Psychology, no. 74, 1968, pp. 97–102, published by John Wiley & Sons Limited. Reproduced with permission.)

THE IMPORTANCE OF BODY LANGUAGE

According to Mehrabian, in our face-to-face communication with other people the

message about our feelings and attitudes come only 7 per cent from the words we

use, 38 per cent from our voice and 55 per cent from body language, including

facial expressions. Significantly, when body language such as gestures and tone of

voice conflicts with the words, greater emphasis is likely to be placed on the non-

verbal message.

34

Although actual percentages may vary, there appears to be general support for

this contention. For example, according to Pivcevic: ‘It is commonly agreed that 80

per cent of communication is non-verbal; it is carried in your posture and gestures,

and in the tone, pace and energy behind what you say’.

35

And McGuire suggests

when verbal and non-verbal messages are in conflict: ‘Accepted wisdom from the

experts is that the non-verbal signals should be the ones to reply on, and that

what is not said is frequently louder than what is said, revealing attitudes and feel-

ings in a way words can’t express.’

36

In our perceptions and judgement of others it is important therefore to watch and take

careful note of their non-verbal communication. However, although body language may

be a guide to personality, errors can easily arise if too much is inferred from a single mes-

sage rather than a related cluster of actions. According to Fletcher, for example: ‘you

won’t learn to interpret people’s body language accurately, and use your own to maxi-

mum effect, without working at it. If you consciously spend half an hour a day analysing

people’s subconscious movements, you’ll soon learn how to do it – almost uncon-

sciously’.

38

However, as Mann points out, with a little knowledge about the subject it is

all too easy to become body conscious. Posture and gesture can unmask deceivers but it

would be dangerous to assume that everyone who avoids eye contact or rubs their nose

is a fibber. Nevertheless an understanding of non-verbal communication is essential for

managers and other professions where good communication skills are essential.

39

There are many cultural variations in non-verbal communications, the extent of physi-

cal contact, and differences in the way body language is perceived and interpreted.

40

For example, Italians and South Americans tend to show their feelings through intense

body language, while Japanese tend to hide their feelings and have largely eliminated

overt body language from interpersonal communication. When talking to another

person, the British tend to look away spasmodically, but Norwegians typically look

people steadily in the eyes without altering their gaze. When the Dutch point a fore-

finger at their temples this is likely to be a sign of congratulations for a good idea, but

with other cultures the gesture has a less complimentary implication.

In many European countries it is customary to greet people with three or four kisses on

the cheek and pulling the head away may be taken as a sign of impoliteness. All cultures

have specific values related to personal space and ‘comfort zone’. For example, Arabs tend

to stand very close when speaking to another person but most Americans when intro-

duced to a new person will, after shaking hands, move backwards a couple of steps to

place a comfortable space between themselves and the person they have just met.

41

PART 4 THE INDIVIDUAL

454

Cultural

differences

Touching a patient to comfort them would be one of the

most natural gestures for a nurse.

But being touched by a nurse of the opposite sex could

offend an orthodox Jew because being comforted like that

is not welcome in Judaism.

Similarly, touching or removing a Sikh’s turban could

also cause offence because it has deep spiritual and moral

significance.

Now a book has been produced to help staff at

Portsmouth hospitals understand the differences between

ethnic minority groups and avoid unwittingly offending them.

Called the Ethnic Minority Handbook, it contains all the

information doctors and nurses need when dealing with

patients of different religious persuasions.

It was completed by Florise Elliott, Portsmouth Hospitals

NHS Trust’s ethnic health coordinator, who said: ‘It’s always

important for people to be aware of other people’s cultures.

‘This makes staff aware of other cultures and differ-

ences in ways of living.’

The book has sections for Buddhists, Chinese people,

Christians, Mormons, Hindus, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Jews,

Muslims, Sikhs and spiritualism and was compiled with

help from representatives from each culture.

As well as guidance on diet, language, cultures, death

and post-mortems, each section contains contacts hospital

medical staff can ring if they need advice.

One is Jewish spokesman Julius Klein, a member of the

Portsmouth and Southsea Hebrew Congregation, who wel-

comed the book.

He said: ‘It’s excellent. One of the difficulties when

people go into hospital is trying to put over certain things

about their culture and life that the hospital needs to know.

‘Anything that helps inform the nursing staff about

minorities must be a good thing.’

Each ward at Queen Alexandra Hospital, Cosham, and

St Mary’s Hospital, Milton, will have a copy of the book

which was started by the hospital’s service planning man-

ager Petronella Mwasandube.

About 1,500 of the 37,500 annual cases the hospitals

deal with are people from ethnic minority groups which

does not include emergencies.

(Reproduced courtesy of The News, Portsmouth, 16 February 1999.)

Hospitals set to play it by ethnic book

Staff receive guide to help them tend people from different cultures, writes Tanya Johnson

EXHIBIT 11.1