Mullins L.J. Management and organisational behaviour, Seventh edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Common challenges for all management

Hannington refers to the need to continuously improve productivity faster than the

competition as the challenge for all management in both the private and public sec-

tors. Management theories apply to all managers and both sectors face a central factor

of the management of change.

In the public sector the challenge may be measured in different ways to those in the private

sector. Profit may not play a part, but measurement of activity against costs may replace monitor-

ing of the return on capital invested. Income is now often linked to output and outcomes, while

expenditure is firmly controlled and audited. Public sector managers are increasingly being

asked to manage their organisations in a more commercial and effective way, exposed to compe-

tition without any guarantee of survival. In many areas, public sector management is little

different from that in the private sector, with the same urgencies and pressures. This is exempli-

fied by the increasing frequency of movement between the two sectors.

32

And as Drucker points out although there are, of course, differences in management

between different organisations, the differences are mainly in application rather than

in principles.

There are not even tremendous differences in tasks and challenges. The executives of all these

organizations spend, for instance, about the same amount of their time on people problems –

and the people problems are almost always the same. Ninety per cent or so of what each

organization is concerned with is generic. And the differences in respect of the last 10 per cent

are no greater between businesses and nonbusinesses than they are between businesses in

different industries.

33

Fenlon also suggests that ‘public and private leadership are fundamentally alike and

different in important respects’. Although public sector executives also confront

unique challenges in every aspect of their leadership, the essentials of leadership and

management in the public sector are the same as those in the private sector. In both

sectors classical managerial activities are required such as designing organisational

structures and processes that support strategies, building systems for staffing, budget-

ing and planning, and measuring results. While public sector executives must also

develop strategies that create benefits, as opposed to profits, at an acceptable rate of

return on political capital employed, the skills of leading and managing are funda-

mentally alike.

34

However, according to Stewart, the belief that one should manage the public sector in

the same way as the private sector is an illusion of our times. Within all categories of

work there are critical differences in the nature of management depending on the tasks

to be undertaken and their context. The good manager will be one who recognises the

need to relate their management style and approach to context and task, and this is as

important in the public sector as in the private sector. The management of difference

can be seen at work in local government, where the sheer diversity of services means

that different services are managed in different ways. Stewart maintains that many of

the dominant management approaches advocated for local government assume a uni-

formity of approach which promises to ignore difference. The belief in a generic type

of management for all situations can be misleading in that it conceals the need for the

hard analysis of the nature of task and context.

35

CHAPTER 6 THE NATURE OF MANAGEMENT

205

The importance

of task and

context

Despite similarities in the general activities of management, the jobs of individual

managers will differ widely. The work of the manager is varied and fragmented. In

practice, it will be influenced by such factors as:

■ the nature of the organisation, its philosophy, objectives and size;

■ the type of structure;

■ activities and tasks involved;

■ technology and methods of performing work;

■ the nature of people employed; and

■ the level in the organisation at which the manager is working.

These differences do not just exist between organisations in the private and public sec-

tors; they are often more a matter of degree. For example, many large business

organisations may have more in common in their management and operations with

public sector organisations than with small private firms.

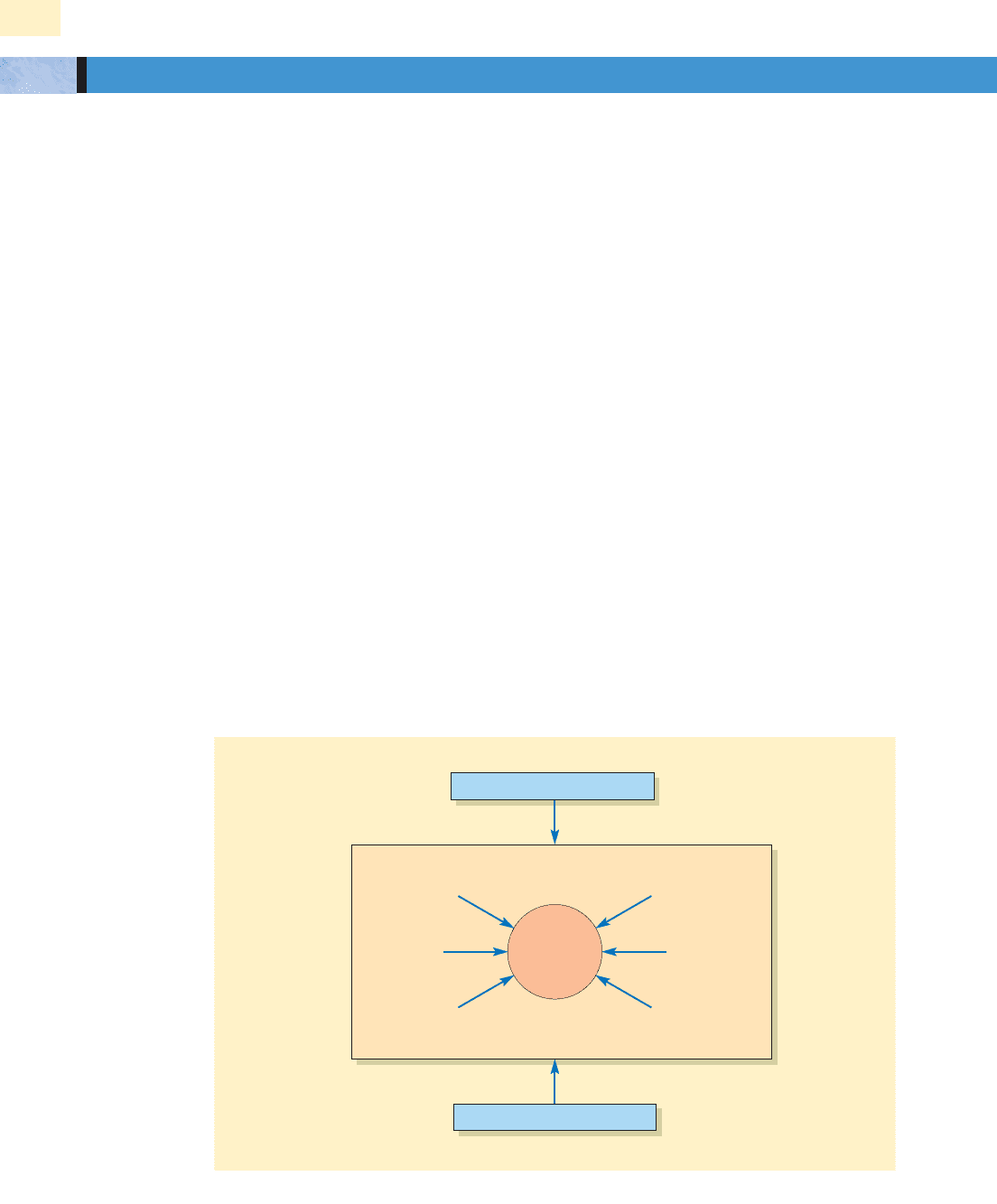

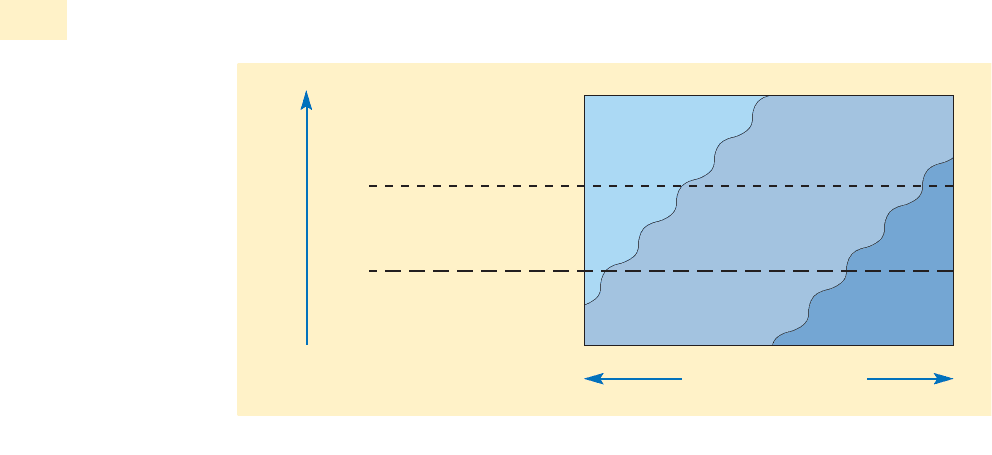

A major determinant of the work of the manager is the nature of the environment,

both internal and external, in which the manager is working. Managers have to per-

form their jobs in the situation in which they find themselves. (See Figure 6.5.)

The internal environment relates to the culture and climate of the organisation – ‘how

things are done around here’ – and to the prevailing atmosphere surrounding the

organisation. Organisational culture and climate are discussed in Chapter 22.

The external environment relates to the organisation as an open system, as discussed

in Chapter 4. Managers must be responsive to the changing opportunities and chal-

lenges, and risks and limitations facing the organisation. External environmental

factors are largely outside the control of management.

206

PART 3 THE ROLE OF THE MANAGER

The

environmental

setting

THE

MANAGER

INTERNAL ENVIRONMENT

Nature of the

organisation

Activities

and tasks

People

Level in the

organisation

Technology

and methods

Structure

INTERNAL ENVIRONMENT

EXTERNAL ENVIRONMENT

EXTERNAL ENVIRONMENT

Figure 6.5 The work of a manager – the environmental setting

THE WORK OF A MANAGER

More recent studies on the nature of management have been based on wider observa-

tion and research, and have concentrated on the diversity of management and

differences in the jobs of managers. Among the best-known empirical studies on the

nature of managers’ jobs, and how managers actually spend their time, are those by

Mintzberg, Kotter, Luthans and Stewart.

36

Based on the study of the work of five chief executives of medium-sized to large organ-

isations, Mintzberg classifies the activities which constitute the essential functions of a

top manager’s job.

37

What managers do cannot be related to the classical view of the

activities of management. The manager’s job can be described more meaningfully in

terms of various ‘roles’ or organised sets of behaviour associated with a position.

38

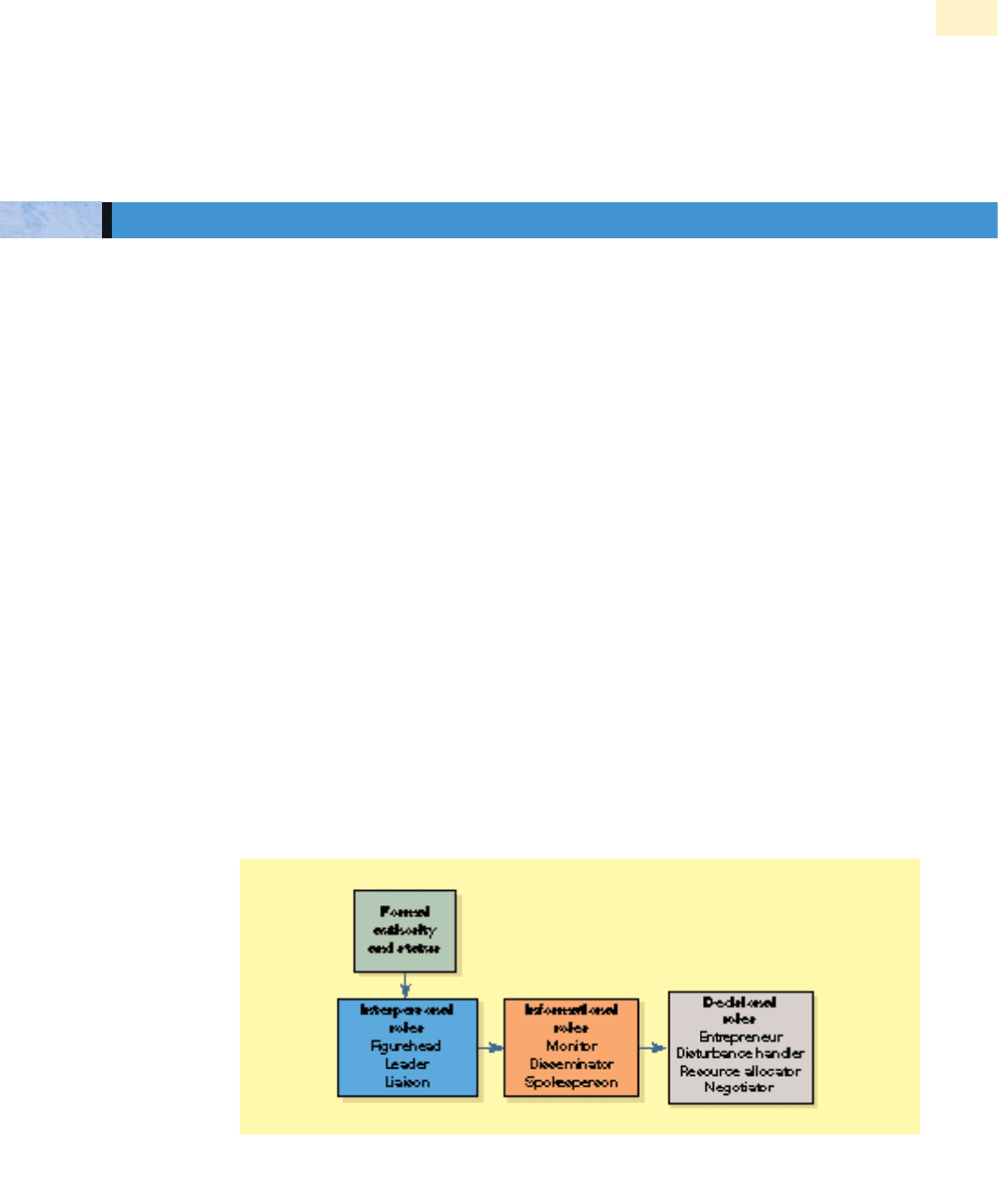

Mintzberg recognises that people who ‘manage’ have formal authority over the unit

they command, and this leads to a special position of status in the organisation.

As a result of this formal authority and status, managerial activities can be seen as a

set of ten managerial roles which may be divided into three groups: (i) interpersonal

roles; (ii) informational roles; and (iii) decisional roles (see Figure 6.6).

The interpersonal roles are relations with other people arising from the manager’s

status and authority.

1 Figurehead role is the most basic and simple of managerial roles. The manager is a

symbol and represents the organisation in matters of formality. The manager is

involved in matters of a ceremonial nature, such as the signing of documents, par-

ticipation as a social necessity, and being available for people who insist on access to

the ‘top’.

2 Leader role is among the most significant of roles and it permeates all activities of a

manager. By virtue of the authority vested in the manager there is a responsibility

for staffing, and for the motivation and guidance of subordinates.

3 Liaison role involves the manager in horizontal relationships with individuals and

groups outside their own unit, or outside the organisation. An important part of the

manager’s job is the linking between the organisation and the environment.

CHAPTER 6 THE NATURE OF MANAGEMENT

207

The diversity of

management

Figure 6.6 The manager’s roles

(Reprinted by permission of the Harvard Business Review from ‘The Manager’s Job: Folklore and Fact’, by Henry Mintzberg, HBR Classic,

March–April 1990, p. 168. Copyright © 1990 by Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation; all rights reserved.)

MANAGERIAL ROLES

Interpersonal

roles

The informational roles relate to the sources and communication of information aris-

ing from the manager’s interpersonal roles.

4 Monitor role identifies the manager in seeking and receiving information. This

information enables the manager to develop an understanding of the working of the

organisation and its environment. Information may be received from internal or

external sources, and may be formal or informal.

5 Disseminator role involves the manager in transmitting external information

through the liaison role into the organisation, and internal information through

leader role between the subordinates. The information may be largely factual or may

contain value judgements. The manager is the nerve centre of information. If the

manager feels unable, or chooses not, to pass on information this can present diffi-

culties for delegation.

6 Spokesperson role involves the manager as formal authority in transmitting infor-

mation to people outside the unit, such as the board of directors or other superiors,

and the general public such as suppliers, customers, government departments and

the press.

The decisional roles involve the making of strategic organisational decisions on the

basis of the manager’s status and authority, and access to information.

7 Entrepreneurial role is the manager’s function to initiate and plan controlled (that

is, voluntary) change through exploiting opportunities or solving problems, and

taking action to improve the existing situation. The manager may play a major

part, personally, in seeking improvement, or may delegate responsibility to subordi-

nates.

8 Disturbance handler role involves the manager in reacting to involuntary situa-

tions and unpredictable events. When an unexpected disturbance occurs the

manager must take action to correct the situation.

9

Resource allocator role involves the manager in using formal authority to decide

where effort will be expended, and making choices on the allocation of resources such

as money, time, materials and staff. The manager decides the programming of work

and maintains control by authorising important decisions before implementation.

10 Negotiator role is participation in negotiation activity with other individuals or

organisations, for example a new agreement with a trade union. Because of the

manager’s authority, credibility, access to information, and responsibility for

resource allocation, negotiation is an important part of the job.

Arbitrary division of activities

Mintzberg emphasises that this set of ten roles is a somewhat arbitrary division of the man-

ager’s activities. It presents one of many possible ways of categorising the view of managerial

roles. The ten roles are not easily isolated in practice but form an integrated whole. If any

role is removed this affects the effectiveness of the manager’s overall performance.

The ten roles suggest that the manager is in fact a specialist required to perform a

particular set of specialised roles. Mintzberg argues that empirical evidence supports

the contention that this set of roles is common to the work of all managers. An exam-

ple of this is provided by Wolf who analysed the work of the audit manager and

assigned critical task requirements to the ten managerial roles identified by

Mintzberg.

39

Another example is the study by Shortt who undertook a Mintzbergian

analysis of 62 general managers of inns in Northern Ireland.

40

Mintzberg’s model of managerial roles is a positive attempt to provide a realistic

approach to classifying the actual activities of management. There are, however, criti-

208

PART 3 THE ROLE OF THE MANAGER

Informational

roles

Decisional

roles

cisms that the roles lack specificity and that a number of items under each role are

related not to a single factor but to several factors. For example, McCall and Segrist

found that activities involved in figurehead, disseminator, disturbance handler and

negotiator were not separate roles but overlapped too much with activities under the

six other roles.

41

As a result of describing the nature of managerial work in terms of a set of ten roles,

Mintzberg suggests six basic purposes of the manager, or reasons why organisations

need managers:

■ to ensure the organisation serves its basic purpose – the efficient production of

goods or services;

■ to design and maintain the stability of the operations of the organisation;

■ to take charge of strategy-making and adapt the organisation in a controlled way to

changes in its environment;

■ to ensure the organisation serves the ends of those people who control it;

■ to serve as the key informational link between the organisation and the environ-

ment; and

■ as formal authority to operate the organisation’s status system.

From a detailed study of 15 successful American general managers involved in a broad

range of industries, Kotter found that although their jobs differed and the managers

undertook their jobs in a different manner they all had two significant activities in

common: agenda-setting and network-building.

42

■ Agenda-setting is a constant activity of managers. This is a set of items, or series of

agendas involving aims and objectives, plans, strategies, ideas, decisions to be made

and priorities of action in order to bring about desired end-results. For example, the

University of Portsmouth strategic plan sets ‘the target of moving into the top third

of universities in Britain over the next ten years’. This requires individual managers

responsible for achieving this target to have a continual and changing series of

agendas to help bring this intention into reality.

■ Network-building involves the managers interacting with other people and estab-

lishing a network of co-operative relations. These networks are outside of the formal

structure. They have often included a very large number of people, many of whom

were in addition to their boss or direct subordinates, and also included individuals

and groups outside the organisation. Meetings provided exchanges of information

over a wide range of topics in a short period of time. A major feature of network-

building was to establish and maintain contacts that could assist in the successful

achievement of agenda items.

On the basis of interviews, observations, questionnaires and relevant documents,

Kotter found the following features of a typical pattern of daily behaviour for a general

manager (GM).

43

1 They spent most of their time with others.

2 The people they spent time with included many in addition to their superior and

direct subordinates.

3 The breadth of topics covered in discussions was very wide.

4 In these conversations GMs typically asked a lot of questions.

5During these conversations GMs rarely seemed to make ‘big’ decisions.

6 Discussions usually contained a considerable amount of joking, kidding, and non-

work-related issues.

CHAPTER 6 THE NATURE OF MANAGEMENT

209

Why

organisations

need managers

BEHAVIOUR PATTERN OF GENERAL MANAGERS

7 In not a small number of these encounters, the substantive issue discussed was rela-

tively unimportant to the business or organisation.

8 In such encounters, the GMs rarely gave ‘orders’ in a traditional sense.

9 Nevertheless, GMs frequently attempted to influence others.

10 In allocation of time with other people, GMs often reacted to the initiatives of others.

11 Most of their time with others was spent in short, disjointed conversations.

12 They worked long hours. (The average GM studied worked just under 60 hours per

week. Although some work was done at home, and while commuting or travelling,

they spent most of their time at work.)

Developing the work of Mintzberg and Kotter, Luthans and associates undertook a

major investigation into the true nature of managerial work through the observation

of 44 ‘real’ managers.

44

A detailed record was maintained of the behaviours and actions

of managers from all levels and many types of organisations, mostly in the service

sector and a few manufacturing companies. The data collected was reduced into 12

descriptive behavioural categories under four managerial activities of real managers.

■ Communication – exchanging information, paperwork.

■ Traditional management – planning, decision-making, controlling.

■ Networking – interacting with outsiders, socialising/politicking.

■ Human resource management – motivating/reinforcing, disciplining/punishing,

managing conflict, staffing, training/developing.

Following determination of the nature of managerial activity, Luthans then went on to

study a further, different set of 248 real managers in order to document the relative fre-

quency of the four main activities. Trained observers completed a checklist at random

times once every hour over a two-week period. The time and effort spent on the four

activities varied among different managers. The ‘average’ manager, however, spent

32 per cent of time and effort on traditional management activities; 29 per cent on

communication activities; 20 per cent on human resource management activities; and

19 per cent on networking activities.

Based on earlier studies of managerial jobs,

45

Stewart has developed a model for under-

standing managerial work and behaviour.

46

The model directs attention to the

generalisations that can be made about managerial work, and differences which exist

among managerial jobs. It acknowledges the wide variety, found from previous studies,

among different managers in similar jobs in terms of how they view their jobs and the

work they do.

Demands, constraints and choices

The three main categories of the model are demands, constraints and choices. These

identify the flexibility in a managerial job.

■ Demands are what anyone in the job has to do. They are not what the manager

ought to do, but only what must be done: for example, meeting minimum criteria

of performance, work which requires personal involvement, complying with bureau-

cratic procedures which cannot be avoided, meetings that must be attended.

210

PART 3 THE ROLE OF THE MANAGER

DETERMINING WHAT REAL MANAGERS DO

Frequency of

activities

PATTERNS OF MANAGERIAL WORK AND BEHAVIOUR

■ Constraints are internal or external factors which limit what the manager can do:

for example, resource limitations, legal or trade union constraints, the nature of

technology, physical location, organisational constraints, attitudes of other people.

■ Choices are the activities that the manager is free to do, but does not have to do.

They are opportunities for one job-holder to undertake different work from another,

or to do the work in a different way: for example, what work is done within a

defined area, to change the area of work, the sharing of work, participation in organ-

isational or public activities.

Stewart suggests that the model provides a framework for thinking about the nature of

managerial jobs, and about the manner in which managers undertake them. To under-

stand what managerial jobs are really like it is necessary to understand the nature of

their flexibility. Account should be taken of variations in behaviour and differences in

jobs before attempting to generalise about managerial work. Study of managers in simi-

lar jobs indicates that their focus of attention differs. Opportunities for individual

managers to do what they believe to be most important exist to a greater or lesser

extent in all managerial jobs. Stewart also concludes that the model has implications

for organisational design, job design, management effectiveness, selection, education

and training, and career decisions.

47

From a review of research into managerial behaviour, Stewart concludes that the pic-

ture built up gives a very different impression from the traditional description of a

manager as one who plans, organises, co-ordinates, motivates, and controls in a logi-

cal, ordered process. Management is very much a human activity.

The picture that emerges from studies of what managers do is of someone who lives in a whirl of

activity, in which attention must be switched every few minutes from one subject, problem, and

person to another; of an uncertain world where relevant information includes gossip and specu-

lation about how other people are thinking and what they are likely to do; and where it is

necessary, particularly in senior posts, to develop a network of people who can fill one in on what

is going on and what is likely to happen. It is a picture, too, not of a manager who sits quietly

controlling but who is dependent upon many people, other than subordinates, with whom recip-

rocating relationships should be created; who needs to learn how to trade, bargain, and

compromise; and a picture of managers who, increasingly as they ascend the management

ladder, live in a political world where they must learn how to influence people other than subor-

dinates, how to manoeuvre, and how to enlist support for what they want to do. In short, it is a

much more human activity than that commonly suggested in management textbooks.

48

Whatever the role of the manager or whether in the private or public sector, in order to

carry out the process of management and the execution of work, the manager requires a

combination of technical competence, social and human skills, and conceptual ability.

49

As the manager advances up the organisational hierarchy, greater emphasis is likely

to be placed on conceptual ability, and proportionately less on technical competence.

This can be illustrated by reference to the levels of organisation discussed in Chapter

15. (See Figure 6.7.)

■ Technical competence relates to the application of specific knowledge, methods and

skills to discrete tasks. Technical competence is likely to be required more at the

supervisory level and for the training of subordinate staff, and with day-to-day oper-

ations concerned in the actual production of goods or services.

CHAPTER 6 THE NATURE OF MANAGEMENT

211

The flexibility

of managerial

jobs

How managers

really behave

THE ATTRIBUTES AND QUALITIES OF A MANAGER

■

Social and human

skills

refer to interpersonal relationships in working with and through

other people, and the exercise of judgement. A distinctive feature of management is

the ability to secure the effective use of the human resources of the organisation. This

involves effective teamwork and the direction and leadership of staff to achieve co-

ordinated effort. Under this heading can be included sensitivity to particular situations,

and flexibility in adopting the most appropriate style of management.

■ Conceptual ability is required in order to view the complexities of the operations of

the organisation as a whole, including environmental influences. It also involves

decision-making skills. The manager’s personal contribution should be related to the

overall objectives of the organisation and to its strategic planning.

Although a simplistic approach, this framework provides a useful basis from which to

examine the combination and balance of the attributes of an effective manager. For

example the extent of technical competence or conceptual ability will vary according to

the level of the organisation at which the manager is working. However, major techno-

logical change means that managers at all levels of the organisation increasingly require

technical competence in the skills of information communications technology (ICT).

50

Balance of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ skills

Management has become more about managing people than managing operations, how-

ever, and social and human skills which reflect the ability to get along with other people

are increasingly important attributes at all levels of management. Green, for example, sug-

gests that most managers will spend most time operating between the spectrum of ‘hard’

skills such as conducting disciplinary matters or fighting one’s corner in a debate about

allocation of budgets; and ‘soft’ skills such as counselling, or giving support and advice to

a member of staff. The most successful managers are those able to adjust their approach

and response to an appropriate part of the spectrum.

51

And as Douglas, for example, also reminds us, although there is a clear need for mastery

of technical expertise, ‘soft skills’ are also an essential part of the world of business.

Living as we do in a society that is technologically and scientifically extremely advanced, most

kinds of professional advancementare close to impossible without the mastery of one or more

specialised branches of systematic technical knowledge … What is the downside? Organisations

in most sectors – and especially in ones that are particularly demanding from a scientific or tech-

nical point of view – are operating in environments where collaboration, teamwork, and an

awareness of the commercial implications of technical research are as importantasscientific and

212

PART 3 THE ROLE OF THE MANAGER

Organisational level

Attributes of a manager

Community

Managerial

Technical

Conceptual ability

Social and human skills

Technical competence

Figure 6.7 The combination of attributes of a manager

technical skills themselves. Personnel with scientific and technical skills significantly dispropor-

tionate to their ‘people’ skills – by which I primarily mean people management capabilities and

knowledge of how to work with maximum effectiveness as part of a team – are increasingly

unlikely to be as much of an asset to their organisation as they ought to be.

52

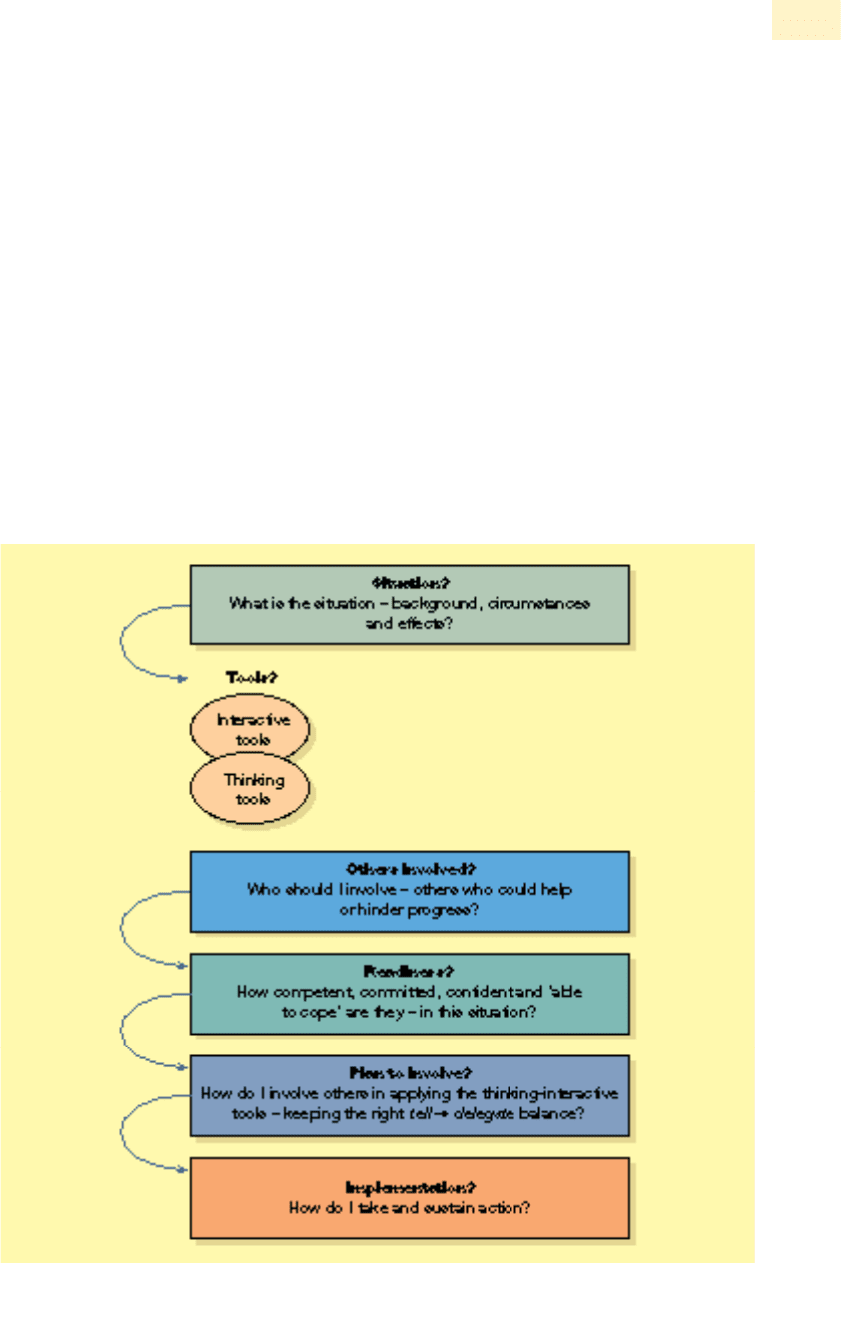

Situational management

According to Misslehorn the challenge for managers is to sharpen their ability to perceive

more accurately, process the information more wisely, respond more appropriately and

examine the feedback from the actions taken in order to learn and keep things on track.

Managers need to think through situations, bringing their rational and creative brain-

power to bear on them. They also need to involve others through appropriate interaction

and communication. The way managers think about the situation and interact with others

have a direct bearing on their perceptions of the situation – helping to curb some of the

distortions from their past experience, values, bias, fears, feelings and prejudices. And the

way managers think about a situation and interact with others also have a direct bearing

on their responses, and the results produced and outcomes of their actions. This interplay

between thinking and interacting takes place in complex strategic organisational situa-

tions. This process of situational management is illustrated in Figure 6.8.

53

CHAPTER 6 THE NATURE OF MANAGEMENT

213

Figure 6.8 Situational management

Reproduced with permission from Hugo Misselhorn, The Head and Heart of Management, Management and Organization Development

Consultants (2003), p. 13.

Delegation and empowerment

We referred earlier to management as getting work done through the efforts of other

people. This entails the process of delegation and empowerment, and entrusting

authority and responsibilities to others. Delegation is not just the arbitrary shedding of

work or the issuing and following of orders. It is an essential social skill and the cre-

ation of a special manager–subordinate relationship within the formal structure of the

organisation. The nature of delegation and empowerment is discussed in Chapter 21.

The importance and reponsibility of management

Whatever the essential nature of managerial work is said to be, the importance and

responsibility of management are widely, and rightly, recognised. For example, accord-

ing to Drucker:

The responsibility of management in our society is decisive not only for the enterprise itself but

for management’s public standing, its success and status, for the very future of our economic

and social system and the survival of the enterprise as an autonomous institution.

54

More recently, Drucker, in discussing management challenges for the twenty-first cen-

tury, also suggests a new management paradigm:

Management’s concern and management’s responsibility are everything that affects the per-

formance of the institution, and its results – whether inside or outside, whether under the

institution’s control or totally beyond it.

55

The ‘Quality of Management’ is one of nine ingredients of success by which Management

Today rate performance in their annual survey of Britain’s Most Admired Companies. In

2003 The Investors in People introduced a ‘Leadership and Management Model’ that

focuses on the development of organisational leadership and management capability.

The model is discussed in Chapter 23.

Billsberry points out that the number of people who are managers has been growing

rapidly and also that the scope and variety of what managers are required to do has

been continually expanding.

56

By contrast, however, Belbin contends that many of the

quintessential managerial activities that fell within the everyday domain of the man-

ager, such as communicating, motivating and organising, have now become shared

with an assortment of well-educated executives such as technical experts, advisers and

specialists, including human resource professionals, industrial relations officers and

consulting firms. Responsibility for direction of effort and setting objectives is taken

over by directors. Managers in the traditional sense of ‘a person who assigns tasks and

responsibilities to others’ have become a dwindling minority. This has had cultural

consequences.

The flattening of hierarchy in opening up opportunities to non-managerial executives has helped

to create resistance to the authority and status of the manager–boss.

57

Whatever the debate, we should note the comments of Heller who from his study of

Europe’s top companies refers to the need for new managers and new methods to obey

the imperatives of a dramatically changed environment.

Today, managements whose minds and deeds are stuck in the status quo are obsolescent, weak

and failing. In the next fewyears, they will be obsolete – and failed. Renewal and nimbleness

have become paramount necessities for the large and established. For the younger business,

staying new and agile is equally imperative.

58

214

PART 3 THE ROLE OF THE MANAGER

MANAGERS OF THE FUTURE?

Ten key

strategies