Mullins L.J. Management and organisational behaviour, Seventh edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ties effectively. Profit does at least provide some broad measure of effectiveness and

highlights the difficulty in evaluating the effectiveness of not-for-profit organisations,

such as National Health Service hospitals, prisons or universities.

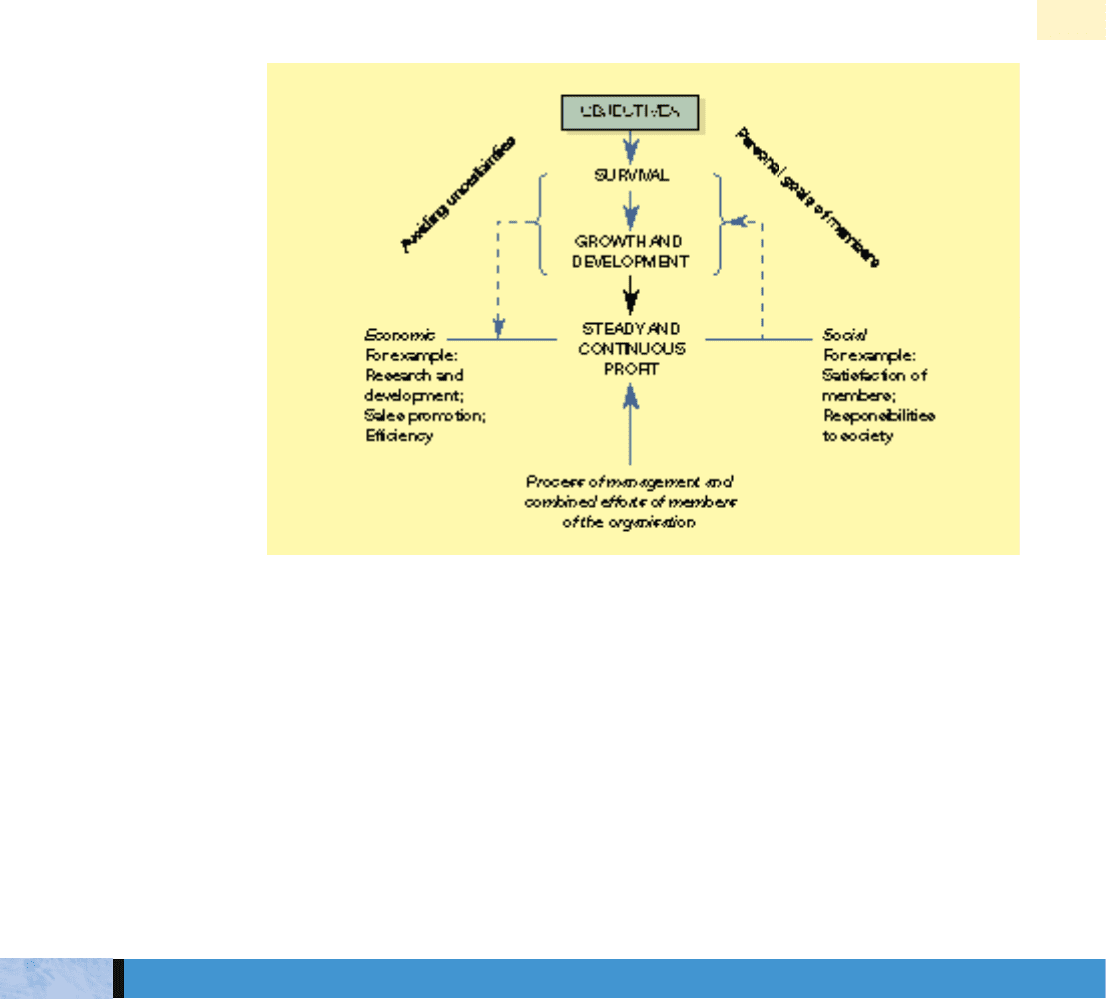

Managers are more concerned with avoiding uncertainties than with prediction of

uncertainties. Economic models of decision-making, based on the assumption of

rational behaviour in choosing from known alternatives in order to maximise objec-

tives, can be contrasted with behavioural models based not so much on maximising of

objectives as on short-term expediency where a choice is made to avoid conflict and

within limiting constraints.

30

Furthermore, as discussed earlier, members of the organisation will have their own

personal goals and their own perception of the goals of the organisation.

Drucker has referred to the fallacy of the single objective of a business. The search for

the one, right objective is not only unlikely to be productive, but is certain to harm

and misdirect the business enterprise.

To emphasize only profit, for instance, misdirects managers to the point where they may endan-

ger the survival of the business. To obtain profit today they tend to undermine the future … To

manage a business is to balance a variety of needs and goals … the very nature of business

enterprise requires multiple objectives which are needed in every area where performance and

results directly and vitally affect the survival and prosperity of the business.

31

Drucker goes on to suggest eight key areas in which objectives should be set in terms of

performance and results:

1 Market standing – for example: share of market standing; range of products and

markets; distribution; pricing; customer loyalty and satisfaction.

CHAPTER 5 ORGANISATIONAL GOALS, STRATEGY AND RESPONSIBILITIES

155

Figure 5.3 Objectives of a business organisation

Avoiding

uncertainties

FALLACY OF THE SINGLE OBJECTIVE

2 Innovation – for example: innovations to reach marketing goals; developments aris-

ing from technological advancements; new processes and improvements in all

major areas of organisational activity.

3 Productivity – for example: optimum use of resources; use of techniques such as

operational research to help decide alternative courses of action; the ratio of ‘con-

tributed value’ to total revenue.

4 Physical and financial resources – for example: physical facilities such as plant,

machines, offices and replacement of facilities; supply of capital and budgeting;

planning for the money needed; provision of supplies.

5 Profitability – for example: profitability forecasts and anticipated timescales; capital

investment policy; yardsticks for measurement of profitability.

6 Manager performance and development – for example: the direction of managers

and setting up their jobs; the structure of management; the development of future

managers.

7 Worker performance and attitude – for example: union relations; the organisation

of work; employee relations.

8 Public responsibility – for example: demands made upon the organisation, such as

by law or public opinion; responsibilities to society and the public interest.

The organisation therefore must give attention to all those areas which are of direct

and vital importance to its survival and prosperity. Etzioni makes the point that:

The systems model, however, leads one to conclude that just as there may be too little allocation

of resources to meet the goals of the organization, so there may also be an over-allocation of

these resources. The systems model explicitlyrecognizes that the organization solves certain

problems other than those directly involved in the achievement of the goal, and that excessive

concern with the latter may result in insufficient attention to other necessary organizational activ-

ities, and to a lack of coordination between the inflated goal activities and the de-emphasized

non-goal activities.

32

Individuals in the organisation are not necessarily guided at all times by the primary

goal(s) of the organisation. Simon illustrates this in respect of the profit goal.

Profit may not enter directly into the decision-making of most members of a business organisa-

tion. Again, this does not mean that it is improper or meaningless to regard profit as a principal

goal of the business. It simply means that the decision-making mechanism is a loosely coupled

system in which the profit constraint is only one among a number of constraints and enters into

most sub-systems only in indirect ways.

33

We have seen, then, that although the profit objective is clearly of importance, by itself

it is not a sufficient criterion for the effective management of a business organisation.

There are many other considerations and motivations which affect the desire for the

greatest profit or maximum economic efficiency.

The balanced score card is an attempt to combine a range of both qualitative and

quantitative indicators of performance which recognise the expectations of various

stakeholders and relates performance to a choice of strategy as a basis for evaluating

organisational effectiveness. Citing the work of Kaplan and Norton in a year-long study

of a dozen US companies,

34

Anita van de Vliet refers to the approach of a ‘balanced

scorecard’ and the belief that:

... relying primarily on financial accounting measures was leading to short-term decision-

making, over-investment in easily valued assets (through mergers and acquisitions) with

readily measurable returns, and under-investment in intangible assets, such as product and

process innovation, employee skills or customer satisfaction, whose short-term returns are

more difficult to measure.

156

PART 2 THE ORGANISATIONAL SETTING

Allocation of

resources and

decision-

making

The balanced

scorecard

Van de Vliet suggests that in the information era, there is a growing consensus that

financial indicators on their own are not an adequate measure of company competi-

tiveness or performance and there is a need to promote a broader view.

The balanced scorecard does still include the hard financial indicators, but it balances these with

other, so-called soft measures, such as customer acquisition, retention, profitability and satisfac-

tion; product development cycle times; employee satisfaction; intellectual assets and

organisational learning.

35

The balanced scorecard (BS) can also be used in the public sector where there is an

increasing need for organisations to improve their performance and to be seen as more

businesslike in the delivery of services (including an employee perspective).

Given that the public sector has the difficult task of fulfilling a wide range of very different objec-

tives, the BS could help in formal recognition and measurement of these objectives.

36

Objectives and policy are formalised within the framework of a corporate strategy which

serves to describe an organisation’s sense of purpose, and plans and actions for its

implementation. Tilles has suggested that without an explicit statement of strategy it

becomes more difficult for expanding organisations to reconcile co-ordinated action

with entrepreneurial effort.

37

An explicit strategy for the business organisation is neces-

sary for the following reasons. First, there is the need for people to co-operate together

in order to achieve the benefits of mutual reinforcement. Second, there are the effects

of changing environmental conditions.

The absence of an explicit concept of strategy may result in members of the organi-

sation working at cross-purposes. The intentions of top management may not be

communicated clearly to those at lower levels in the hierarchy who are expected to

implement these intentions. Obsolete patterns of behaviour become very difficult to

modify. Change comes about from either subjective or intuitive assessment, which

become increasingly unreliable as the rate of change increases. Developing a statement

of strategy demands a creative effort. If strategic planning is to be successful, it requires

different methods of behaviour and often fundamental change in the nature of inter-

actions among managers.

38

Allen and Helms suggest that different types of reward practices may more closely

complement different generic strategies and are significantly related to higher levels of

perceived organisational performance.

39

Increased business competitiveness and the dynamic external environment have

placed important emphasis on corporate strategy and the competencies of managers.

For example, Richardson and Thompson argue that if organisations are to be effective in

strategic terms they must be able to deal with the pressures and demands of change.

Managers should be strategically aware and appreciate the origins and nature of

change. They should possess a comprehensive set of skills and competencies and be

able to deal effectively with the forces which represent opportunities and threats to the

organisation. Effective strategic management creates a productive alliance between the

nature and the demands of the environment, the organisation’s culture and values,

and the resources that the organisation has at its disposal.

40

Strategy is about first asking questions, then improving the quality of those questions through

listening to the answers and acting on the new knowledge. Any effective strategy requires the

successful integration of thoughts about tomorrow’s new business opportunities with both past

experience and the pattern of today’s behaviours.

41

CHAPTER 5 ORGANISATIONAL GOALS, STRATEGY AND RESPONSIBILITIES

157

THE NEED FOR STRATEGY

Managers’

skills and

competencies

Some form of corporate strategy or planning is necessary for all organisations, particu-

larly large organisations and including service organisations and those in the public

sector. In a discussion on strategy developments, Lynch suggests that many of the same

considerations apply to both public and private organisations. The major difference

has been the lack of the objective to deliver a profit in government-owned institutions.

The trend in most parts of the world is now towards privatising large public companies

in the utilities and telecommunications sectors. The principal impact of privatisation

on strategy will depend on the form that privatisation takes. Some companies may

remain monopolies even though in the private sector. Lynch sets out the following key

strategic principles for public and non-profit organisations:

■ Public organisations are unlikely to have a profit objective. Strategy is therefore

governed by broader public policy issues such as politics, monopoly supply, bureau-

cracy and the battle for resources from the government to fund the activities of

the organisation.

■ Strategy in non-profit organisations needs to reflect the values held by the institu-

tions concerned. Decision-making may be slower and more complex.

■ Within the constraints outlined above, the basic strategic principles can then be

applied.

42

In the public sector, the establishment of objectives and policy requires clarification of

the respective roles of both elected members and permanent officials. This dual nature

of management requires harmonious relationships between the two parties and

emphasises the need for a corporate approach.

43

A strategic framework

In order to continue in existence and succeed, Bruce maintains that a business needs a

structured strategic framework which provides the starting point for moving forward

and a means for assessing and responding to change. The strategic framework defines

the boundary in terms of product markets and is reflected in the management of

processes, knowledge and people. Bruce sets out a strategic framework divided into five

separate but interrelated elements:

■ the things that are driving strategic decisions;

■ the direction that the organisation is heading in;

■ the products and services that will be delivered;

■ the design of the organisation’s processes, knowledge systems and people develop-

ment mechanisms;

■ the specific targets that will identify whether the organisation is deviating from

its plan.

Once strategic targets have been agreed the organisation or team must be aligned. The

review should start with the means to deliver the strategy before reviewing the formal

structure and hierarchies. Then the selection, development and leadership of people

should be reviewed to create a work environment and culture that supports each ele-

ment of the strategic framework.

44

An important aspect of corporate strategy and the growth and development of organi-

sations is the concept of synergy which was developed in management applications by

Ansoff.

45

Synergy results when the whole is greater than the sum of its component

parts. It can be expressed, simply, in terms of the 2 + 2 = 5 effect.

158

PART 2 THE ORGANISATIONAL SETTING

Corporate

approach in

the public

sector

THE CONCEPT OF SYNERGY

Synergy is usually experienced in situations of expansion or where one organisation

merges with another, such as an organisation responsible for the development and pro-

duction of a product merging with an organisation which markets the product. An

example could be a television manufacturer merging with a television rental organisa-

tion. The new organisation could benefit from the combined strengths and

opportunities, skills and expertise, shared fixed overheads and technology, and from

the streamlining and economy of its operations. Another example could be the merger

of a computer firm with expertise in the design and marketing of hardware, with a firm

expert in software manufacture and systems design.

It is possible, however, to experience negative synergy or the 2 + 2 = 3 situation.

Such a situation might arise when a merger occurs between organisations operating in

different fields, with different markets or with different methods, or where the new

organisation becomes unwieldy or loses its cost-effectiveness.

Ansoff has also referred to the analysis of strengths and weaknesses of organisations fol-

lowing the formulation of objectives;

46

and to threats and opportunities in the process

of strategic change.

47

This can be developed into what is a commonly known acronym,

SWOT analysis (sometimes also known as ‘WOTS up’), which focuses on the Strengths,

Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats facing organisations.

The SWOT analysis provides convenient headings under which to study an organi-

sation in its environmental setting and may provide a basis for decision-making and

problem-solving. You may therefore find the analysis helpful in tackling case studies.

■ Strengths are those positive aspects or distinctive attributes or competencies which

provide a significant market advantage or upon which the organisation can build –

for example, through the pursuit of diversification. These are characteristics of the

organisation such as present market position, size, structure, managerial expertise,

physical or financial resources, staffing, image or reputation. By searching out

opportunities which match its strengths the organisation can optimise the effects

of synergy.

■ Weaknesses are those negative aspects or deficiencies in the present competencies

or resources of the organisation, or its image or reputation, which limit its effective-

ness and which need to be corrected or need action taken to minimise their effect.

Examples of weaknesses could be operating within a particular narrow market, lim-

ited accommodation or outdated equipment, a high proportion of fixed costs, a

bureaucratic structure, a high level of customer complaints or a shortage of key

managerial staff.

■ Opportunities are favourable conditions and usually arise from the nature of

changes in the external environment. The organisation needs to be sensitive to the

problems of business strategy and responsive to changes in, for example, new mar-

kets, technology advances, improved economic factors, or failure of competitors.

Opportunities provide the potential for the organisation to offer new, or to develop

existing, products, facilities or services.

■ Threats are the converse of opportunities and refer to unfavourable situations which

arise from external developments likely to endanger the operations and effectiveness

of the organisation. Examples could include changes in legislation, the introduction

of a radically new product by competitors, political or economic unrest, changing

social conditions and the actions of pressure groups. Organisations need to be

responsive to changes that have already occurred and to plan for anticipated signifi-

cant changes in the environment and to be prepared to meet them.

CHAPTER 5 ORGANISATIONAL GOALS, STRATEGY AND RESPONSIBILITIES

159

SWOT ANALYSIS

Although SWOT can offer a number of potential advantages for helping to evaluate

corporate performance, care must be taken that the process does not lead to an over-

simplified and misleading analysis. There are many ways of evaluating organisational

performance and effectiveness, and varying criteria for success. For example, Levine

suggests that the new criteria for assessing the strength of an organisation will be in

the area of quality results achieved through people.

48

Every business needs to have a strategy and this strategy must be related to changing

environmental conditions. In order to survive and maintain growth and expansion top

management must protect the business from potentially harmful influences, and be

ready to take maximum advantage of the challenges and opportunities presented.

While top management must always accept the need for innovation there is still the

decision as to which opportunities it wishes to develop in relation to its resources, and

those it chooses not to pursue. An effective business strategy depends upon the suc-

cessful management of opportunities and risks.

Drucker suggests that strategy should be based on the priority of maximising

opportunities, and that risks should be viewed not as grounds of action but as limita-

tions on action.

49

Drucker points out that while it is not possible to ensure that the right opportunities

are chosen, it is certain that the right opportunities will not be selected unless:

■ the focus is on maximising opportunities rather than on minimising risks;

■ major opportunities are scrutinised collectively and in respect of their characteristics

rather than singly and in isolation;

■ opportunities and risks are understood in terms of the appropriateness of their fit to

a particular business; and

■ a balance is struck between immediate and easy opportunities for improvement, and

more difficult, long-range opportunities for innovation and changing the character

of the business.

If the business is to be successful then its organisation structure must be related to its

objectives and to its strategy. The structure must be designed so as to be appropriate to

environmental influences, the continued development of the business, and the man-

agement of opportunities and risks. The nature of organisation structure is discussed in

Chapter 15.

E-business strategies

Advances in information technology and the Internet mean that organisations have to

embrace successful e-commerce and e-business strategies. For example, according to Earl:

Quite simply, IT affects businessstrategy. It is an input to business strategy as well as an

output. The Internet, mobile communications, and future media present both threats and

opportunities. So business strategy that ignores how technology is changing markets, competi-

tion, and processes is a process for the old economy, not the new economy. That is what

‘e-everything’ is about.

50

Kermally points out that in order to operate within the new macro-economic environ-

ment, organisations have to seriously consider the arrival of the new economy and

strategies. They have to embrace e-business in order to deal with the complexity of the

new business environment. Apart from scenario planning, e-businesses also have to

focus special attention to recruiting and retaining staff. It is important to keep up with

160

PART 2 THE ORGANISATIONAL SETTING

THE MANAGEMENT OF OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS

competitors and not to become complacent about adopting e-business. Kermally main-

tains that the e-business model is important because it:

■ makes it possible for information to be shared more quickly and easily;

■ facilitates human interaction;

■ enables organisational resources and capabilities to be stretch strategically;

■ provides global reach in marketing;

■ allows consumers to shop 24 hours a day from any location; and

■ promotes economic growth.

51

Organisations play a major and increasingly important role in the lives of us all,

especially with the growth of large-scale business and the divorce of ownership from

management. The decisions and actions of management in organisations have an

increasing impact on individuals, other organisations and the community. The power

and influence which many business organisations now exercise should be tempered,

therefore, by an attitude of responsibility by management.

In striving to satisfy its goals and achieve its objectives the organisation cannot

operate in isolation from the environment of which it is part. The organisation

requires the use of factors of production and other facilities of society. The economic

efficiency of organisations is affected by governmental, social, technical and cultural

variables. In return, society is in need of the goods and services created and supplied by

organisations, including the creation and distribution of wealth. Organisations make a

contribution to the quality of life and to the well-being of the community.

Organisational survival is dependent upon a series of exchanges between the organi-

sation and its environment. These exchanges and the continual interaction with the

environment give rise to a number of broader responsibilities to society in general.

These broader responsibilities, which are both internal and external to the organisa-

tion, are usually referred to as social responsibilities. These social responsibilities arise

from the interdependence of organisations, society and the environment.

The recognition of the importance of social responsibilities can be gauged in part by

the extent of government action and legislation on such matters as, for example,

employment protection, equal opportunities, companies acts, consumer law, product

liability and safeguarding the environment. This has formalised certain areas of social

responsibilities into a legal requirement. It is doubtful, however, if legislation alone is

sufficient to make management, or other members of an organisation, behave in what

might be regarded as a ‘proper’ manner.

There has been a growing attention to the subject of social responsibilities and an

increasing amount of literature on the subject and on a new work ethic. The impor-

tance of social responsibility (or corporate responsibility) can also be gauged by the

amount of coverage in the annual review of most major companies. For example,

under the heading of Corporate Responsibility the annual review of the BG Group

refers to the Statement of Business Principles and to eight key policies which cover:

personal conduct; human resources; governance; human rights; communications;

health, safety and environment; security; and corporate conduct.

52

Many businesses

both in the UK and other parts of Europe are attempting to provide a more open and

transparent view of their operations.

53

The European Commission is encouraging firms

to assess their performance not on profit margins alone but also on the welfare of their

workforce and care for the environment.

54

CHAPTER 5 ORGANISATIONAL GOALS, STRATEGY AND RESPONSIBILITIES

161

SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITIES OF ORGANISATIONS

Growing

attention to

social

responsibilities

Shortland points out that consumer activism has never been more intense and the

media very rapidly exposes unethical practices. Society, consumers, shareholders and

legislators all require companies to be more transparent and accountable.

The concept of social responsiveness means that companies respond to stakeholders and con-

cern from society by considering more than just the company’s own interests. Systematic

evaluation of the needs for stakeholders can position the company to be socially responsible.

However, companies cannot simply take a reactive approach to issues as they arise, the princi-

ples must be embedded in the corporate culture and business strategy, right through to the

day-to-day decision-making process. Companies that embrace the principles of social responsi-

bility and ethics in a proactive manner are the companies of the future – the firms that will

survive and prosper.

55

Global responsibilities

Today there is also greater concern for business communities to accept their global

responsibilities. This is recognised, for example, in the foreward to a book by Grayson

and Hodges, by HRH The Prince of Wales.

An increasing number of organisations, of all types, are now publishing a Code of

Conduct (or Code of Ethics). For example, the Chartered Management Institute have a

‘Code of professional management practice’ that sets out the professional standards

required of members of the Institute as a condition of membership as regards:

1 the individual manager;

2 others within the organisation;

3the organisation;

4 others external to but in direct relationship with the organisation;

5the wider community;

6 the Chartered Management Institute.

57

Extracts from the Code of Conduct of IBM Ltd are given in Management in Action

5.1 at the end of this chapter.

Codes of conduct are very common in American and Canadian organisations and in

many cases members of the organisation are required to sign to indicate formally their

162

PART 2 THE ORGANISATIONAL SETTING

For the business community of the twenty-first century, ‘out of sight’ is no longer ‘out of

mind’. Global communications and media operations can present every aspect of a com-

pany’s operations directly to customers in stark, unflattering and immediate terms. Those

customers increasingly believe that the role of large companies in our society must encom-

pass more than the traditional functions of obeying the law, paying taxes and making a

profit. Survey after survey reveals that they also want to see major corporations helping ‘to

make the world a better place’. That may be in some respects a naïve ambition, but it is,

nevertheless, a clear expectation, and one that companies ignore at their peril … It is

immensely encouraging to find that there are business leaders who recognise the challenge

of running their companies in ways that make a positive and sustainable contribution to the

societies in which they operate. It is a huge task, not least in finding ways of reaching out to

the thousands of managers at the ‘sharp end’ of the business who, every day, take the deci-

sions that have real impact on employees, on whole communities and on the environment.

HRH The Prince of Wales

56

CODES OF CONDUCT

acceptance of the code. Codes may be updated on a regular basis and in some cases

such as investment companies this may be at least once a year.

In the public sector, the Local Government Act 2000 specifies the following princi-

ples to govern the conduct of members of relevant English authorities and Welsh

police authorities: selflessness, honesty and integrity, objectivity, accountability, open-

ness, personal judgement, respect for others, duty to uphold the law, stewardship and

leadership. These principles are intended to underpin the mandatory provisions of the

model codes of conduct for English local authorities.

58

Tam poses the basic question, ‘Can we live with an idea of “good” management which

cannot be ultimately reconciled with what is good for society?’ and maintains that:

... the time has come for us to recognise that the only sustainable form of good management is that

which takes into account the full range of responsibilities that underpin organisational success.

59

It should, however, be recognised that the distinction is blurred between the exercise of

a genuine social responsibility, on the one hand, and actions taken in pursuit of good

business practice and the search for organisational efficiency on the other. One

approach is that attention to social responsibilities arises out of a moral or ethical moti-

vation and the dictates of conscience – that is, out of genuine philanthropic objectives.

An alternative approach is that the motivation is through no more than enlightened

self-interest and the belief that, in the long term, attention to social responsibilities is

simply good business sense. In practice, it is a matter of degree and balance, of com-

bining sound economic management with an appropriate concern for broader

responsibilities to society.

Altman et al. point to a revolution going on which is changing the way we live and

work, and question whether the leaders of giant companies are in tune with the social

problems that surround them, affecting both employees and customers.

We believe there is more than a hint that many business leaders lack a strong moral underpinning

awareness and concern for the proliferation of social problems, that business is increasing behav-

ing in an amoral fashion. Recent comment has tended to suggest that there is a general lack of

concern for the spread of social problems for which industry must take a share of responsibility.

There is a strong suspicion that business leaders are primarily focused on short-term issues, such

as shareholder value, rather than seeking to balance the shareholder/stakeholder equation.

60

Allen, however, questions whether the emphasis on the caring sharing company of the

new millennium and social responsibility is all going a bit far. There is scarcely a com-

pany without a loftily worded mission statement and high-minded references to

shareholders. There are now numerous codes and standards and any company wishing

to keep up to date with latest developments in social responsibility needs to look in

many directions at once, and companies are talking of ‘codemania’. While many codes

offer voluntary guidelines, companies that fail to meet these can see themselves receiv-

ing a bad press or disinvestments. Nevertheless, the burden of social responsibilities

can be seen as part of the response to ever-changing social conditions.

61

And, accord-

ing to Cook, although it is easy to be cynical following the fall of big companies there

are many organisations who are ‘putting something back’. There is evidence about

reversing the decline in public trusts and that in response to stakeholder and customer

attitudes, corporate values are changing.

62

We have seen that social responsibilities are often viewed in terms of organisational

stakeholders – that is, those individuals or groups who have an interest in and/or are

affected by the goals, operations or activities of the organisation or the behaviour of its

CHAPTER 5 ORGANISATIONAL GOALS, STRATEGY AND RESPONSIBILITIES

163

A matter of

degree and

balance

ORGANISATIONAL STAKEHOLDERS

members.

63

Managers, for example, are likely to have a particular interest in, and con-

cern for, the size and growth of the organisation and its profitability, job security,

status, power and prestige. Stakeholders, on the other hand, include a wide variety of

interests and may be considered, for example, under six main headings of:

■ employees;

■ providers of finance;

■ consumers;

■ community and environment;

■ government; and

■ other organisations or groups.

People and organisations need each other. Social responsibilities to employees extend

beyond terms and conditions of the formal contract of employment and give recogni-

tion to the worker as a human being. People today have wider expectations of the

quality of working life, including: justice in treatment; democratic functioning of the

organisation and opportunities for consultation and participation; training in new

skills and technologies; effective personnel and employment relations policies and

practices; and provision of social and leisure facilities. Organisations should also, for

example, give due consideration to the design of work organisation and job satisfac-

tion, make every reasonable effort to give security of employment, and provide

employment opportunities for minority groups. Responsibilities to employees involve

considerations of the new psychological contracts discussed in Chapter 2. In the case

of public authorities regard must also be paid to the provisions of the Human Rights

Act 1998.

Joint stock companies are in need of the collective investments of shareholders in

order to finance their operations. Shareholders are drawn from a wide range of the

population. The conversion of a number of building societies and insurance companies

from mutual societies to public companies extended significantly the range of share

ownership and stakeholding among private individuals. Many people also subscribe

indirectly as shareholders through pension funds and insurance companies.

Shareholders expect a fair financial return as payment for risk bearing and the use of

their capital. In addition, social responsibilities of management extend to include the

safeguarding of investments, and the opportunity for shareholders to exercise their

responsibility as owners of the company, to participate in policy decisions and to ques-

tion top management on the affairs of the company. Management has a responsibility

to declare personal interests, and to provide shareholders with full information pre-

sented in a readily understood form. In the case of public sector organisations, finance

may be provided by government grants/subsidies – which are funded ‘compulsorily’ by

the public through taxation and rates – as well as loans, and charges for services pro-

vided. There is, therefore, a similar range of social responsibilities to the public as

subscribers of capital.

To many people, responsibilities to consumers may be seen as no more than a

natural outcome of good business. There are, however, broader social responsibilities

including:

■ providing good value for money;

■ the safety and durability of products/services;

■ standard of after-sales service;

■ prompt and courteous attention to queries and complaints;

■ long-term satisfaction – for example, serviceability, adequate supply of products/

services, and spare and replacement parts;

164

PART 2 THE ORGANISATIONAL SETTING

Employees

Providers of

finance

Consumers