Moyar Mark. A Question of Command: Counterinsurgency from the Civil War to Iraq

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

60 Reconstruction in the South

ern whites and broke the will of Northern whites to impose egalitarian racial

policies.

Northern Republicans could have made Reconstruction more palatable to

Southern whites by introducing political and social change more gradually,

although it is not certain that Northern public opinion would have accepted

such gradualism in the late 1860s. eir worst mistake was supplanting the

existing Southern elites with Carpetbaggers, Scalawags, and blacks. e Radi-

cal Republicans did more than enough to alienate the traditional elites but not

enough to destroy or even seriously reduce their inuence over the popula-

tion. Taking away the elites’ rights to vote and hold oce did not prevent them

from mounting resistance through insurgency and, later, through democratic

elections. Given the strong traditional loyalties of Southern whites, perma-

nent neutralization of the native white elites would have required the barbarity

of the French, Russian, and Chinese revolutions, which the American people

would never have accepted and which, in any case, would have been as disas-

trous in America as it was in France, Russia, and China.

e Northern Radicals failed to introduce new elites who could have

wrested inuence away from the old elites. Committing a common and oen

fatal error in counterinsurgency, they did not properly gauge the merits of

the elites whom they were empowering. Some overestimated the quality of

the newly created elites, while others fell victim to the fallacy that leadership

quality varies little from one group to the next. Nor was much eort made to

balance considerations of merit against considerations of politics in leadership

appointments; the scales almost always tipped too heavily toward politics. e

Carpetbaggers, Scalawags, and blacks lacked the initiative, integrity, and dedi-

cation necessary to gain and maintain the support of the South’s white popu-

lation. ey failed to build militia and police forces capable of safeguarding the

people’s security and instead jeopardized the people’s security by elding un-

ruly militiamen. Rather than inspiring the people with moral rectitude, they

alienated them with rigged elections, biased justice, and pilferage from the

public coers.

If the South’s traditional leaders had been adamantly opposed to any ad-

vancement for blacks, the Republicans could perhaps have been excused for

trying to circumvent them. But that was not the case. Many of these leaders

had supported the Republican Party in the pre-Radical phase of Reconstruc-

tion, and most others were willing to accept a moderate form of Reconstruc-

tion. Although the white elites objected to the drastic nature and rapid pace of

Reconstruction in the South 61

change envisioned by Northerners, the federal government almost certainly

could have done more for blacks by gradually nudging these whites along and

forging an enduring partnership than by undertaking the Radical program

and losing practically everything. Had it not been for the imposition of the

new, ineective elites during Radical Reconstruction, Southern and Northern

whites would not have been so receptive in 1877 to the idea of eliminating

federal oversight of the South or to the idea of rescinding most of the political

rights gained by blacks since the Civil War.

In contrast to the state governments of Radical Reconstruction, the U.S.

Army could boast that its leaders in the South included hundreds of accom-

plished men. But commanders who had vanquished their Confederate foes in

the big conventional battles of the Civil War oen proved less eective in com-

bating insurgents. Some, including Grant and Sheridan, failed to cope with

the ambiguities and compromises of the political side of counterinsurgency

because they were, by temperament, much less comfortable with counterin-

surgency than with conventional warfare. Some lacked the empathy, integrity,

or organizational talent to keep their troops from harming the civilian popu-

lation. ose who shared Sheridan’s contempt for the entire white South could

hardly work eectively with the local whites.

At the same time, the army did have some commanders who were cut out

perfectly for counterinsurgency duty. Ocers like Major General Charles H.

Smith and Major Lewis Merrill possessed the right attributes and brought

much grief to the insurgents, whether by cultivating white elites, gathering in-

formation with skill and vigor, or insisting on impartial treatment of the local

population. But top authorities in the army and the federal government did

not try very hard to promote such men or bring more of them into the army.

For the U.S. Army, this problem would recur in future wars of insurgency. In

fact, it is still present today.

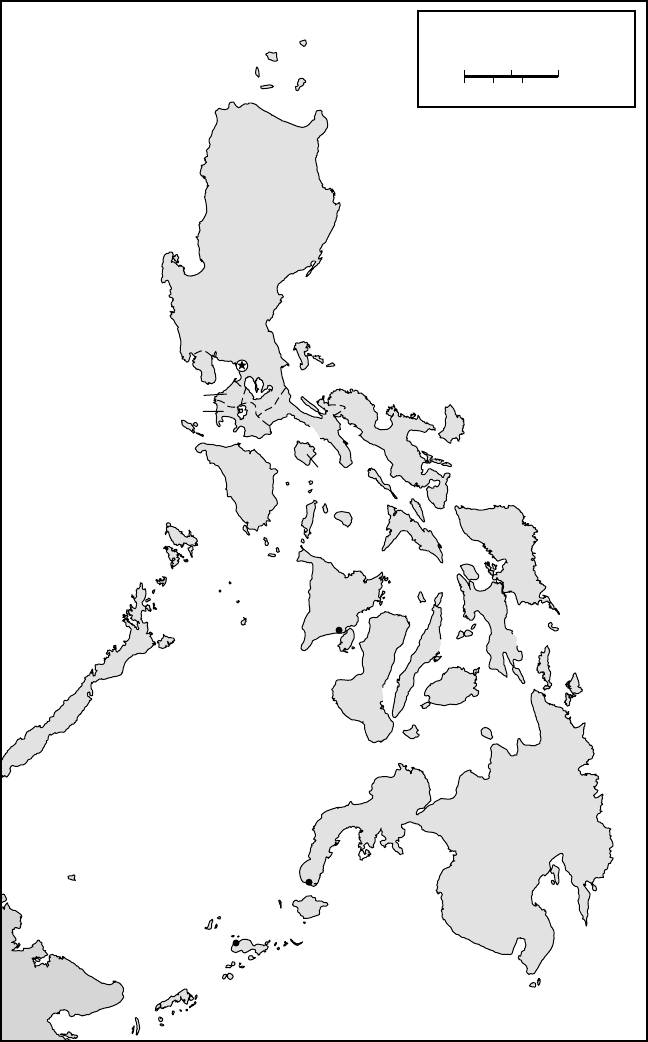

North

Borneo

S

u

l

u

A

r

c

h

i

p

e

l

a

g

o

Dinagat

Bohol

Cebu

Negros

Panay

Leyte

Homonhon

Samar

Visayan

Islands

Catanduanes

Tayabas

Mindanao

Palawan

Mindoro

Bataan

Cavite

Batangas

Luzon

Babuyan Is.

Marinduque

Masbate

Celebes

Sea

Sulu Sea

South

China

Sea

Philippine Sea

Manila

Iloilo

Zamboanga

Jolo

THE PHILIPPINES, 1899

0

50

100 kilometers

0

50

100 miles

63

s the sun rose over Manila Bay, seven American warships chugged for-

ward from the southwest. e agship, the USS Olympia, sported

four 8-inch guns and steel deck plates, and the squadron also had a

“baby battleship” with four 6-inch guns and various other cruisers of 1880s

vintage, members of the last generation of warships propelled by both sail and

steam. e huge Spanish shore guns hurled projectiles at the intruders to no

avail, their rounds plopping harmlessly into the water.

e American ships intended to destroy those guns, but only as a second-

ary objective. What had enticed them to Manila Bay were the seven Span-

ish warships moored at the Cavite navy yard. ough equal in number to the

American ships, the Spanish ships were older, slower, smaller, less heavily

armed, and less thickly armored. Some were made of wood or had enough

wood on board to make excellent tinder. e Spanish ships red rst, at 5:15

a.m., before the American ships were in range. Commodore George Dewey,

commanding the U.S. squadron from the bridge of the Olympia, waited until

the distance had closed to 5,500 yards before ordering his ships to re. At

5:22 a.m., as ship bands played “e Star-Spangled Banner,” 250-pound shells

began vaulting from the turrets of the American cruisers.

e U.S. squadron concentrated its re on the Spanish agship, the Reina

Cristina, and scored one direct hit aer another. Shells took down the mizzen-

mast and the national ag, smashed into the sick bay, the aer magazine, and

the re room, and created a gaping wound in the hull, which spewed steam

from the superheater. When more than half of the 352 Spanish crewmen lay

CHAPTER 4

e Philippine Insurrection

A

64 e Philippine Insurrection

dead or wounded and the magazines stood in danger of exploding, the ship’s

commander ordered the ship to be sunk. e American turrets then swiveled

toward the remaining Spanish ships.

To the astonishment of both sides, rounds from the Spanish ships and

shore batteries dropped all around the American ships but scored very few

hits, and most of the hits caused only supercial damage to decks or rigging.

Only one Spanish round penetrated the hull of an American ship, the Balti-

more, putting a gun out of action and exploding ammunition, but it inicted

only eight minor wounds. Remarkably, no American was killed during the

entire battle.

By 7:30 a.m. all of the Spanish ships were ablaze from the Americans’ me-

thodical salvos, and the Spanish guns were incapable of ring. But the Ameri-

cans did not move in for the kill. Commodore Dewey pulled the otilla back

out of range because of a report—erroneous, it turned out—that some of his

ships were running low on ammunition and needed to restock. As the ships

regrouped, Dewey let all the crewmen have breakfast. ey ate a leisurely meal

of sardines, corned beef, and hardtack and then smoked cigarettes, strolling

the decks as if enjoying a pleasure cruise. e break lasted for nearly three

hours.

Once the battle resumed, the Spaniards endured another couple of hours

of bombardment before deciding to scuttle their eet and run up a white ag

at the shore arsenal. e American squadron landed a party of seven men to

nish the destruction of the vessels in the navy yard, then steamed the short

distance up the coast to Manila, where it took up a menacing position near

the city. at night they could still see the hulls of the Spanish ships burning at

Cavite. Magazines periodically exploded and shot ery debris up hundreds of

feet.

Dewey sent word to the Spanish that if the shore batteries at Manila red

on his squadron, he would pulverize the city with his mighty guns. e Spanish

agreed not to re. Occupying the city was not an option for the United States at

this point, however, for Dewey did not have enough men for the task. Instead,

the American eet undertook a blockade of Manila and awaited troops and

further orders from Washington.1

Commander Dewey had, in a few hours, made what would be the rst step

in America’s march to European-style imperialism. at truth was not, how-

ever, readily visible. President William McKinley had ordered the Manila Bay

attack of May 1, 1898, to hurt the Spanish in the early moments of the Spanish-

e Philippine Insurrection 65

American War and increase his leverage in future negotiations, not to take per-

manent control of the Philippines. He had gone to war with Spain over Cuba,

and then only aer overcoming his own doubts about the wisdom of such a

course. Averse to bloodshed and beholden to businessmen who opposed war

for economic reasons, McKinley had resisted the clamors for war from the

“yellow journalists” of Hearst and Pulitzer and other jingoists like Assistant

Secretary of the Navy eodore Roosevelt. Even aer an ocial American in-

quiry into the explosion of the USS Maine in Havana harbor attributed the

event to a Spanish mine, McKinley had hesitated, eliciting from Roosevelt the

remark that “McKinley has no more backbone than a chocolate éclair.”2 What

ultimately led McKinley to declare war remains a point of contention; it may

have been disgust with Spain’s harsh repression of Cuban rebels, deference to

overwhelming American public opinion, or some other consideration.3

Soon aer the stunning victory at Manila Bay, McKinley ordered the orga-

nization of an American expedition to take Manila and hold it as a bargaining

chip. In the interim, to undermine the Spaniards in the rest of the archipelago,

an American steamer brought ashore an exiled Filipino nationalist named

Emilio Aguinaldo, who in 1896 had started a revolt against Spanish rule. e

Americans gave him a supply of ries, a decision they rued later, when those

ries were turned on the Americans. In June, Aguinaldo declared the Phil-

ippines independent and appointed himself ruler. Few Americans, however,

were paying attention to Aguinaldo at this time, focused as they were on Cuba,

where a clumsy U.S. Army was battling an even clumsier Spanish force.

Manila came back into America’s view in August, following the capitu-

lation of the Spanish forces in Cuba. On August 13, newly arrived American

forces initiated a ground assault on Manila and overwhelmed a tepid Spanish

defense. Aguinaldo and his rebel armed forces sought to enter the city with the

American victors but were kept out, for the Americans feared that the rebels

would, among other things, kill priests and other civilians, as they had done

elsewhere in recent weeks. Aguinaldo responded by cutting o the city’s water

supply and demanding that he be treated as the independent leader of the

Philippines.

In the United States, American public sentiment for annexing the Philip-

pines was on the rise. Many reasons were given. e Philippines could not be

le to Spain, which by now had assumed devilish proportions in American

eyes, nor to the other European imperial powers, which were only margin-

ally better than Spain, nor to Aguinaldo and other Filipinos, who had dem-

66 e Philippine Insurrection

onstrated a mixture of incompetence and tyranny in their early attempts at

governance. Annexation, said its supporters, would enable the United States

to extend its military and economic power and spread its superior civilization.

On October 28, for reasons that remain obscure, McKinley ordered the an-

nexation of the Philippines, and the Senate, aer contentious debate, ratied it

by a vote of y-seven to twenty-seven.

McKinley instructed the expeditionary commander, General Elwell S. Otis,

to extend American control across the Philippine archipelago, a diverse array

of islands extending over 500,000 square miles, home to approximately seven

million people. McKinley instructed the army to remember that “we come,

not as invaders or conquerors, but as friends,” and decreed that “it should be

the earnest and paramount aim of the military administration to win the con-

dence, respect, and aection of the inhabitants of the Philippines by assuring

them in every possible way that full measure of individual rights and liberties

which is the heritage of a free people, and by proving to them that the mission

of the United States is one of benevolent assimilation, substituting the mild

sway of justice and right for arbitrary rule.”4

Aguinaldo continued to insist on Philippine independence, and he built up

a military presence outside Manila that did not go unnoticed in General Otis’s

headquarters. Tensions mounted between Aguinaldo’s forces and the Ameri-

can soldiers. On the night of February 4, 1899, a small number of men from

each side got into a gunght in Manila, which each side accused the other of

starting, and combat exploded across the outskirts of the city like a chain of

recrackers. e next morning American artillery opened up on Aguinaldo’s

main line of defense, on the Santa Mesa Ridge, while American infantrymen

dashed ahead under the artillery smoke. e Filipinos fought back with vary-

ing degrees of intensity and skill and generally little organization. Within a

few hours, the Americans took the blockhouses on the ridge, and during the

aernoon they overran Aguinaldo’s main strong points on the ridge. Most of

Aguinaldo’s forces in Manila were defeated in a single day.

Attacking outward from Manila, the Americans battled Aguinaldo’s Army

of Liberation of the Philippines for the next several months. Aguinaldo had

tried to model his army aer European armies, but the nal product was

merely a patchwork of local volunteer militia units, with neither the leader-

ship nor the training that enabled European and American armies to operate

coherently in large groups. Even when defending fortied positions in ter-

rain ideally suited for defense, Aguinaldo’s rebel forces consistently lost to the

e Philippine Insurrection 67

Americans. But Aguinaldo was able to prolong the war by retreating across

jungles and rivers, where the absence of roads compelled the Americans to

advance at a slog. American operations came to a halt in the summer, when

monsoon rains turned the islands into mud. In the fall, however, the Ameri-

cans returned to the oensive and wiped out most of Aguinaldo’s army before

the season was out. Narrowly evading capture, Aguinaldo ordered his com-

manders to switch from a conventional war to a guerrilla insurgency.

Aguinaldo’s provincial commands retained small groups of regular troops,

armed with ries, who conducted hit-and-run attacks on the Americans and

intimidated or killed Filipino collaborators. Operating out of the archipelago’s

dense jungles, high cogon grass, and mountains, they proved a very dicult

target for the counterinsurgents. More numerous were militiamen who lived

as ordinary civilians. Typically armed with only bolo knives or spears, these

insurgents largely avoided combat and instead concentrated on such as tasks

as moving supplies, setting booby traps, gathering information, and spreading

rumors that the Americans were intent on raping all women.5 Local rebels

with no ties to Aguinaldo controlled most militia forces, and they also oper-

ated shadow governments that collected taxes, recruited civilians into the re-

bellion, and enforced law and order.

In most regions of the Philippines, the insurgent leaders consisted exclu-

sively of men from the principalia, the Filipino upper class, who had taken

to arms to gain independence from foreign control. Redistributing wealth

and altering relations between the upper and lower classes were not on the

agenda. e less auent Filipinos usually supported the rebellion because of

longstanding loyalty to the principalia, although in select provinces they par-

ticipated for a variety of other reasons, such as religion, compulsion by the

insurgents, or local power struggles. As in times past, the peasants obeyed the

dictates of the principalia and gave them a large fraction of their crops, while

the principalia provided land, security, religious ceremonies, and insurance

against poor harvests. Many peasants served in insurgent units commanded

by their own landlords.6

In early 1900, General Otis spread the American occupation forces across

the islands of the archipelago. An ocer in the 140th New York Infantry dur-

ing the Civil War, Otis had distinguished himself in the pivotal ghting on

Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg. In the ensuing decades he

had published articles on military law and American Indians and directed a

long series of administrative and logistical tasks, most recently the transporta-

68 e Philippine Insurrection

tion of American forces to the Philippines, the swiness of which stood in

stark contrast to the appallingly sluggish deployment of American troops to

Cuba. In addition to his considerable intelligence and administrative skills,

Otis had a knack for designing conventional military campaigns.

Otis broke down the conventional forces in the Philippines into small

occupation units and divided command by geographic region. His dispatch in

reorganizing the forces and reorienting them toward civil aairs was impres-

sive. But he had serious aws as a counterinsurgency leader. rough his over-

bearing, self-righteous, and sarcastic comportment, he managed to alienate

American ocers of every rank. His leadership was made even less inspiring

by his dullness and his unappealing appearance—he was oen compared to

a beagle with muttonchop whiskers. His abrasive and boring personality also

guaranteed failure in dealing with the American press, whose reports from the

Philippines had much power to undermine American popular and congres-

sional support for the war. Relying on a leadership style that had served him

well in managing the movement of troops and the acquisition of supplies, Otis

seldom le Manila, which prevented him from staying adequately informed

about the status of the war or the performance of his subordinates. For most

of his long workdays, Otis sat in his oce reviewing the mounds of papers

that covered his desk and the tables he had ordered brought in to hold more

mounds. Details consumed him. When he le his palatial residence and went

into the city, he talked only to the wealthiest segment of Manila society, who

conveyed to him the misleading impression that most Filipino elites favored

American annexation and detested Aguinaldo.7

Otis issued all U.S. commanders some detailed guidance on the methods

they should use and those they could not use, but, being far removed from most

of the ghting, he could not compel commanders to adhere to that guidance.

Some of the departmental and district commanders, occupying positions on

the organizational chart between Otis and the local commanders, attempted

to control the conduct of local counterinsurgency eorts, unwisely taking de-

cisions away from local commanders who possessed superior comprehension

of conditions on the ground. Commanders at the departmental and district

levels were typically appointed based on seniority rather than suitability for the

job, a bureaucratic policy more appropriate for a peacetime army than one at

war. In only a few cases did the army rapidly promote young ocers and pro-

pel them into departmental or district commands, most famously the cases of

Frederick Funston and J. Franklin Bell, both of whom had led brilliantly dur-

e Philippine Insurrection 69

ing the conventional war at home and won Congressional Medals of Honor.

e advisability of supplanting seniority with merit was amply demonstrated

when men like Funston and Bell excelled as counterinsurgency commanders,

while ocers selected based on seniority oen zzled.

A prime case of zzling was Major General John C. Bates. A decent but un-

distinguished eld ocer in the regular army, he was appointed commander

of the department of southern Luzon on the basis of seniority. He spent nearly

all his time in Manila and on his rare visits outside the capital went only to

nearby provinces. His inability to familiarize himself with the realities in the

areas under his command did not stop him from rejecting innovative pro-

posals from the provincial commanders, to the general detriment of the war

eort. Because of his isolation and inattentiveness, he could not identify which

of his subordinates were underperforming, a critical task for an ocer at that

level.8

Intermediate commanders who attempted to micromanage the war from

their perches, especially those with no tact or charisma, drained initiative and

dedication from their subordinates. e best departmental and district com-

manders le most decisions in the hands of local commanders while monitor-

ing them and correcting or replacing the poor performers. Brigadier General

Samuel B. M. Young, commander of the rst district in northern Luzon, epito-

mized this type of leadership. By refusing to force specic actions on his sub-

ordinates and by shielding them from the demands of the central authorities

in Manila, Young promoted creativity and initiative. A ne judge of talent, he

relieved subordinate commanders who were unt for their jobs. Not by coinci-

dence, his district was among the most innovative and successful in combat-

ing the insurgents.9 One other function that intermediate commanders could

and sometimes did perform was the persuasion of Filipino elites to support

the United States.10

Local commanders, even those serving under ocers who sought to

micromanage, enjoyed a great deal of autonomy because distance and terrain

limited the frequency of communications and supervisory visits. Command-

ers in the provinces found ways to disregard or only partially comply with

orders that they considered foolish, which dampened the impact of leadership

weaknesses at higher levels. Consequently, the success or failure of counterin-

surgency depended largely on the overall quality of the pool of junior ocers

and the ability of senior ocers to put the best of the junior ocers into pro-

vincial and post commands. e American leadership did not always place