Mills Martin. Nexus: Student's Book (English for Advanced Learners)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

UNIT

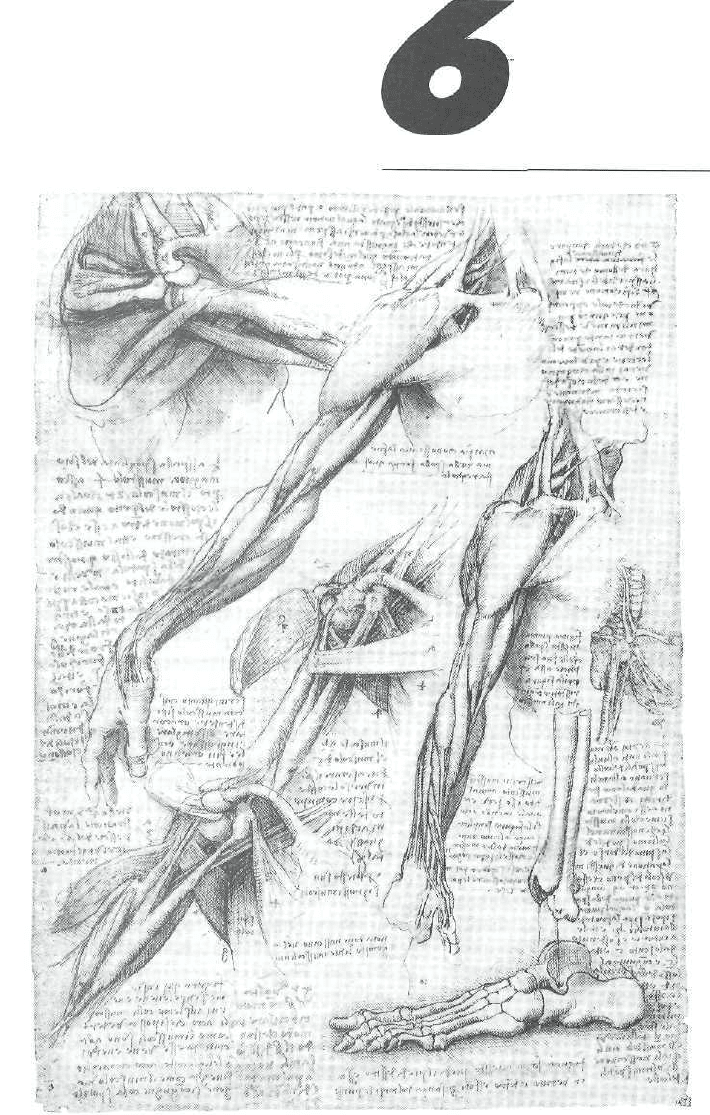

Health and medicine

A Reading 1

A literary' extract: Indian Camp

B Grammar

Making comparative structures more

informative

C Listening

An interview with a GP:

Healthy and wealthy?

D Vocabulary

Idioms based on parts of the body

E Reading 2

A newspaper article: Herbal remedy

F Speaking

Focus on function: tactful advice;

opinions; excuses

G Writing

Guided work: topic sentences

61

UNIT 6

Indian camp

T

HEY came around a bend and a dog came out

barking. Ahead were the lights of the shan-

ties where the Indian bark-peelers lived.

More dogs rushed out at them. The two Indians sent

them back to the shanties. In the shanty nearest the

road there was a light in the window. An old woman

stood in the doorway holding a lamp.

Inside on a wooden bunk lay a young Indian

woman. She had been trying to have her baby for two

days. All the old women in the camp had been help-

ing her. The men had moved off up the road to sit in

the dark and smoke out of range of the noise she

made. She screamed just as Nick and the two Indians

followed his father and Uncle George into the shanty.

She lay in the lower bunk, very big under a quilt.

Her head was turned to one side. In the upper bunk

was her husband. He had cut his foot very badly with

an axe three days before. He was smoking a pipe.

The room smelled very bad.

Nick's father ordered some water to be put on the

stove, and while it was heating he spoke to Nick.

"This lady is going to have a baby, Nick,' he said.

'I know,' said Nick.

'You don't know,' said his father. 'Listen to me.

What she is going through is called being in labour.

The baby wants to be born and she wants it to be

born. All her muscles are trying to get the baby

born. That is what is happening when she screams.'

'I see,' Nick said.

Just then the woman cried out.

'Oh, Daddy, can't you give her something to make

her stop screaming?' asked Nick.

'No. I haven't any anaesthetic,' his father said. 'But

her screams arc not important. I don't hear them

because they are not important."

The husband in the upper bunk rolled over against

the wall.

The woman in the kitchen motioned to the doctor

that the water was hot. Nick's father went into the

kitchen and poured about half of the water out of the

big kettle into a basin. Into the water left in the kettle

he put several things he unwrapped from a

handkerchief.

'Those must boil,' he said, and began to scrub his

hands in the basin of hot water with a cake of soap he

had brought from the camp. Nick watched his fath-

er's hands scrubbing each other with the soap. While

his father washed his hands very carefully and tho-

roughly, he talked.

'You see, Nick, babies are supposed to be born

head first, but sometimes they're not. When they're

not they make a lot of trouble for everybody. Maybe

I'll have to operate on this lady. We'll know in a little

while.'

When he was satisfied with his hands he went in and

went to work.

'Pull back that quilt, will you, George?" he said. 'I'd

rather not touch it.'

Later when he started to operate Uncle George

and three Indian men held the woman still. She bit

Uncle George on the arm and Uncle George said,

L

Damn squaw bitch!' and the young Indian who had

rowed Uncle George over laughed at him. Nick held

the basin for his father. It took a long time.

His father picked the baby up and slapped it to

make it breathe and handed it to the old woman.

62

A | Reading 1

Discussion

• Write a true sentence connecting the following

three things:

primitive peoples (e.g. Indians)

the white man

health

• Think of facts or ideas to support your sentence.

Tell your sentence to your group and explain what

you mean.

Do you think it's better to keep unpleasant realities

like disease and death from children, or is it better

to inform them? What arguments could be made

for each point of view?

Reading exercises

1 The extract opposite is the greater part (including

the end) of a short story by Ernest Hemingway.

Read it and answer the following questions,

working in groups. In many cases the answer must

be inferred.

what is the effect on the focus of the story of

referring to the doctor and his brother as 'Nick's

father' and 'Uncle George'?

What exactly is happening to the Indian lady?

Why does Nick's father say, 'Her screams are not

important'?

How does Nick's father feel after the operation?

Why?

How does Uncle George feel when he says, 'Oh,

you're a great man, all right'?

At what point in the story does the Indian die?

Why do you think Nick and his father walk back

UNIT 6

without Uncle George?

How did they get to the Indian camp in the first

place?

How does Nick feel during the operation? How

does he feel after leaving the camp?

How does Nick's father feel after leaving the camp?

What do you think Hemingway is saying in the story?

2 Hemingway is known for uncomplicated, realistic,

powerful writing, in which words are not wasted.

What aspects of this story make it typical of his

writing?

'See, it's a boy, Nick," he said. 'How do you like

being an interne?'

Nick said, 'All right.' He was looking away so as

Inot to see what his father was doing.

'There. That gets it,' said his father and put

something into the basin.

Nick didn't look at it.

'Now,' his father said, 'there's some stitches to put

in. You can watch this or not, Nick, just as you like.

I'm going to sew up the incision I made.'

Nick did not watch. His curiosity had been gone

for a long time.

His father finished and stood up. Uncle George

and the three Indian men stood up. Nick put the

basin out in the kitchen.

Uncle George looked at his arm. The young

Indian smiled reminiscently.

Til put some peroxide on that, George,' the doctor

said.

He bent over the Indian woman. She was quiet

now and her eyes were closed. She looked very pa!e.

She did not know what had become of the baby or

anything.

Til be back in the morning,' the doctor said, stand-

ing up. 'The nurse should be here from St Ignace by

noon and she'll bring everything we need.'

He was feeling exalted and talkative as football

players are in the dressing-room after a game.

'That's one for the medical journal, George,' he

said. 'Doing a Caesarian with a jack-knife and sew-

ing it up with nine-foot, tapered gut leaders.'

Uncle George was standing against the wall, look-

ing at his arm.

'Oh, you're a great man, all right,' he said.

'Ought to have a look at the proud father. They're

usually the worst sufferers in these little affairs,' the

doctor said. T must say he took it all pretty quietly.'

He pulled back the blanket from the Indian's

head. His hand came away wet. He mounted on the

edge of the lower bunk with the lamp in one hand and

looked in. The Indian lay with his face to the wall.

His throat had been cut from ear to ear. The blood

had flowed down into a pool where his body sagged

the bunk. His head rested on his left arm. The open

razor lay, edge up, in the blankets.

'Take Nick out of the shanty, George,

1

the doctor

said.

There was no need for that. Nick, standing in the

door of the kitchen, had a good view of the upper

bunk when his father, the lamp in one hand, tipped

the Indian's head back.

It was just beginning to be daylight when they

walked along the logging road back towards the lake.

'I'm terribly sorry I brought you along, Nickie,'

said his father, all his post-operative exhilaration

gone. 'It was an awful mess to put you through.'

'Do ladies always have such a hard time having

babies?' Nick asked.

'No, that was very, very exceptional.'

'Why did he kill himself, Daddy?'

T don't know, Nick. He couldn't stand things, I

guess.'

'Do many men kill themselves, Daddy?'

'Not very many, Nick.'

'Do many women?'

'Hardly ever.'

'Don't they ever?'

'Oh, yes. They do sometimes.'

'Daddy?'

'Yes.'

'Where did Uncle George go?'

'He'll turn up all right."

'Is dying hard, Daddy?'

'No, I think it's pretty easy, Nick. It all depends.'

They were seated in the boat, Nick in the stern, his

father rowing. The sun was coming up over the hills.

A bass jumped, making a circle in the water. Nick

trailed his hand in the water. It felt warm in the sharp

chill of the morning.

In the early morning on the lake sitting in the stern

of the boat with his father rowing, he felt quite sure

that he would never die.

Ernest Hemingway Indian Camp

h

i

k

63

UNIT 6

B I Grammar

Making comparative structures more informative

Review

English has two basic comparative-Structures.

Using -er, more, less, fewer

Examples:

With adjectives

Generally older people have more health problems.

Drugs are more expensive than they used to be.

For quantity

There is less disease in Europe than in Africa.

For number

There are fewer hospitals in Africa than in Europe.

With adverbs

/ recovered more quickly than anyone had expected.

Using not as ... as ...

Examples:

With adjectives

Shortages in our ward aren't as bod as in others.

For quantity

1 don't know as much as I should about AIDS.

For number

She doesn't catch as many colds as she used to.

With adverbs

My grandmother doesn't move as quickly as she used to.

These constructions could be more informative,

For example, we do not know how much more

expensive drugs are nowadays, or how many more

hospitals there are in Europe. Discuss ways of

adding to or modifying the constructions to make

them more informative. Consider the use of the

following words and expressions.

far much a bit not nearly even not quite

a great deal slightly twice

Check your ideas on Study page 170.

For each sentence, write another with the same

meaning, using the words in brackets.

Learning to ski is much easier than you might

think, (as)

He isn't nearly as old as I expected, (younger)

Margarine costs a bit less than butter, (much)

Salaries aren't rising nearly as fast as prices, (mum

Nowadays there aren't nearly as many deaths from

typhoid as there used to be. (fewer)

The situation isn't nearly as simple as people think.

(deal)

Your house is twice as big as mine, (size)

He earns twice as much as she does, (half)

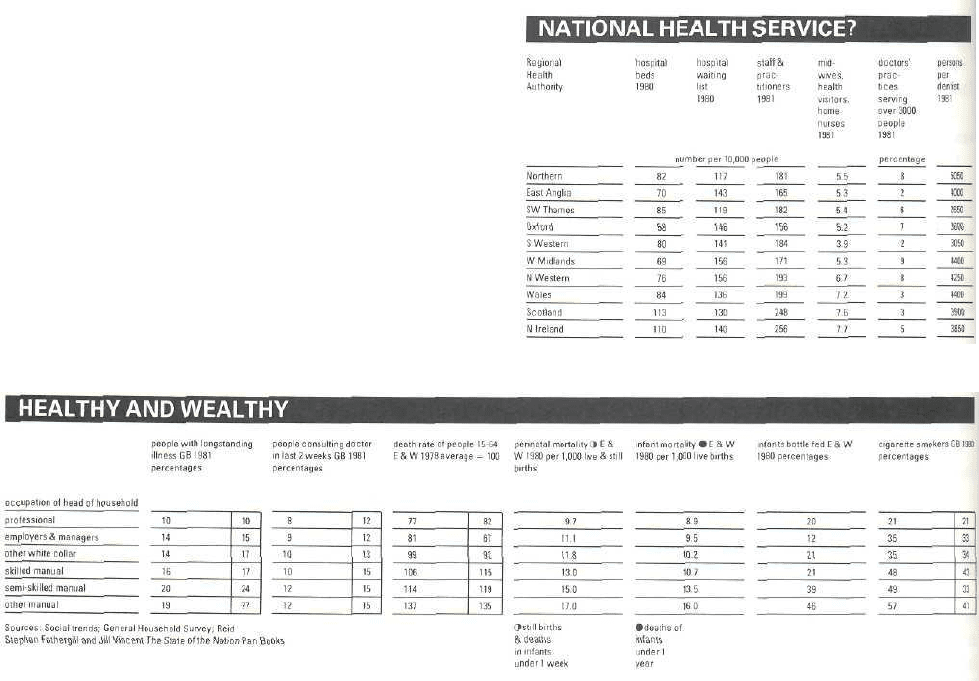

In pairs study the tables below, and use

comparative sentences to express the statistics they

contain. Remember, there is always more than

one way to make the comparison.

Example:

In 1980, hospital waiting lists were much longer inNW

England than they were in SW Thames.

or

In 1980, people in NW England had to wait far longer

for hospital treatment than people in SW Thames.

Using these structures, write ten sentences

comparing your city or country with others.

Consider size, climate, wealth, beauty, interest,

principal cities, the people customs etc. Your

sentences may be factual or your own opinions.

64

b

c

d

e

f

g

h

3

4

1

2

a

UNIT 6

Listening

Healthy and wealthy?

Discussion

The British National Health Service {NHS) is

famous for providing free, good-quality health

care. However, in recent years it has become less

effective, causing much political debate. Some

I people say private, profit-making health

organisations should be encouraged. Others

propose even greater government investment.

• Describe the health system in your own

I country. How much care is provided by the public

health service, and how much by profit-making

organisations?

t What arguments could be put forward for and

against private health care?

Listening exercises

1 Dr Hugh King, a British General Practitioner

•' (GP), discusses the questions of private health

care. As you listen, tick any of the arguments you

noted above which are mentioned by either Dr

King or the interviewer. Also note down any other

arguments mentioned.

2 Listen again, and mark the following statements T

fi (true) or F (false), according to what is said in the

interview.

a In Britain, senior politicians have to use the NHS,

like ordinary citizens.

b A man who is out of work because of a health

condition may wait a long time for his operation.

C Influential people such as politicians can use

private health care, so they don't know that there

are long waiting lists for operations within the

NHS.

Doctor King feels that politicians are more likely to

do something about a problem if they experience it

than if they only know about it.

If waiting would make a patient's condition worse,

the patient doesn't have to wait.

Dr King doesn't agree that private health care takes

pressure off the NHS by treating people who would

otherwise be NHS patients.

What makes waiting lists shorter is hard work from

doctors who believe in the NHS, not patients

leaving the NHS for private care.

Doctors in Britain must either work for the NHS

or provide private health care. They cannot do both.

If a doctor has a private patient and an NHS

patient, and each have exactly the same problem,

it is likely that the former will be treated long

before the latter.

Dr King believes it is wrong that patients should be

able to have nicer food and a mare comfortable

room just because they can afford to pay for them.

Listen again, filling the gaps in the following

sentences. Each line represents a word or

abbreviation.

I'm very private medical care.

.. . removed a very important part of the lobby

which might __ have helped improve health care.

If these people with influence to use the

National Health Service they . .

something done about it.

I think because this quite powerful section of

society can private health care ...

The people who've really done well with their

waiting lists, . —, are pretty

health service doctors.

The worst examples I know of are of people who

deliberately, . - _

make a very obvious contrast between the short

wait...

I mean that's a large part of it, but there are no

doubt, there's no doubt that in

some operations would be done ...

But if money can buy you a bigger car,

money buy you better health care?

Match these meanings to six of the words or

expressions above.

i the part of the economy iv serious, dedicated

not run by the government v if this were not true

ii against vi it seems to me

iii go to, for help

d

e

f

g

h

i

i

3

a

b

c

d

e

f

g

h

4

65

UNIT 6

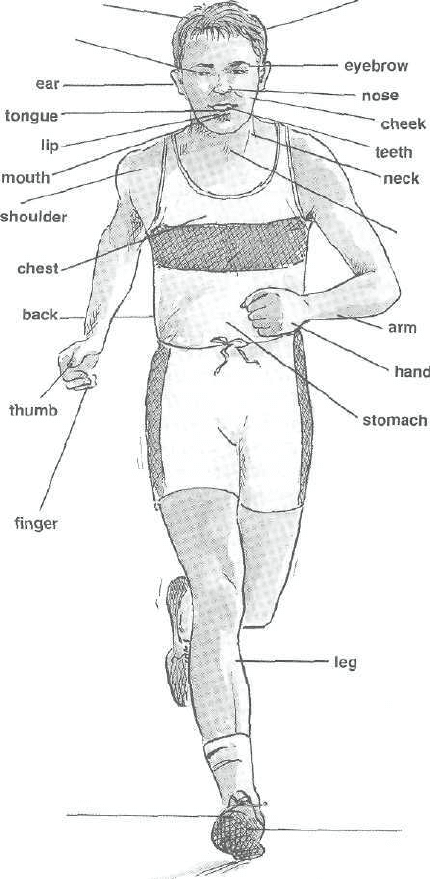

D Vocabulary

Idioms based on ports of the body

1 Many English idiomatic expressions are based on

parts of the body.

Example: No one would blink an eyelid. (Unit 1, D

Reading 2)

Note down any other similar expressions you know.

The picture may help you.

2 Replace the words in italics with expressions using

the words in brackets.

a The thieves were heavily armed, (teeth)

b It's a bit risky. Let's just hope it works out all right.

(fingers).

C He was really unfriendly to me; I think I must have

annoyed him somehow. (back)

d It will be strange at first. It might take you some

time to settle down and get used to it. (feet)

e Are you joking? (leg)

f Don't interfere, it's none of your business, (nose)

g I understood part of the lecture, but most of it was

too difficult for me to understand, (head)

h They don't seem to have the same opinion about

anything, (eye)

i I gave him permission to do what he thought best,

without consulting anyone, (hand)

| Of course you should allow children to do what

they want, within limits, but sometimes you have

to be firm, and not give in. (foot)

k We must act quickly, before the situation gets

completely out of control, (hand)

I The President has Parliament completely under his

influence and control, (thumb)

m Can you keep watch on the kids while I get some

ice-creams? (eye)

n The boss seems to be in a bad mood. He was very

angry and sharp with me when I asked if I could have

tomorrow off. (head)

O Well, it'll be a difficult game, but I'm going to take

a chance and give my opinion. I think Italy will win

it. (neck)

Some expressions in Exercise 2 are more idiomatic

than others. For example, it is harder to

understand how pull someone's leg is derived than

keep an eye on. Can you see how any other

expressions are derived?

hair head

eye

throat

toe

foot

66

UNIT 6

Read this letter, putting expressions from Exercise

fill in the gaps. Each line represents a word.

With a partner, look up more idioms of this type in

your dictionary and choose five which you both

like. Write an exercise like Exercise 2, of five

sentences. Pass it to another pair. Do the exercise

which is passed to you.

oat

67

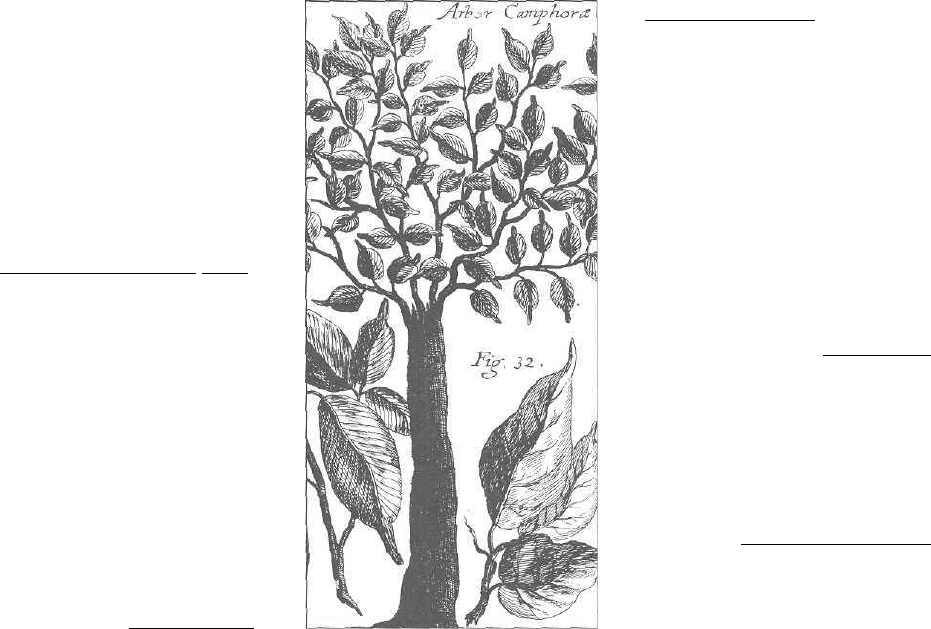

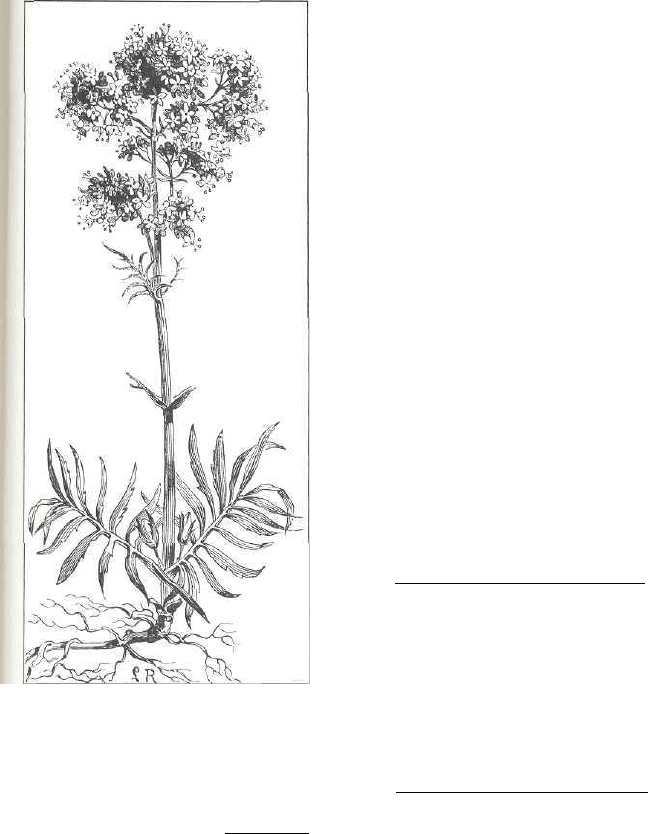

Herbal Remedy

Anthony Swift on medicine for the people, by the people, in the slums of Recife

For the past two months Dr Celerino

Carriconde has been moving between

Kew Gardens and Chelsea College,

London, identifying plant species in

the one and establishing chemical

components in the other in order to

authenticate the knowledge of the

slum dwellers of Recife.

He wants to know, for example, why

lemon grass works as an anti-spas-

modic, why rue can be used as an anti-

biotic against uterus infections and

(1) - . ..

Such herbs and the knowledge local

people have of their healing proper-

ties have provided Dr Carriconde with

a starting point for a health care

regime that has aroused the interest

of conventional physicians.

Essential to the new medicine —

which he believes is being developed

in different countries, including

America — is that the doctor stops

posturing as a provider of health and

encourages people to become active in

securing their own health and to

understand the nature, cures and

causes of disease.

It is totally opposed to the pharma-

ceutical industry, (2) .

, many of them

dangerous and restricted in other

countries, and sold 'like bananas' to

people ignorant of their side effects.

Dr Carriconde got into the new

medicine by a very roundabout route.

He was jailed in 1969 while treating

striking metal workers, was held for

95 days and tortured. On his release

he went into exile, moving from Uru-

guay, to Chile, to Panama, then

Canada.

It has been his choice 'as a Catholic'

to work with the poor, and it was in

Panama while treating an Indian

woman with an infected Caesarean

birth wound that he (3)

'Now I know honey has both bacter-

icide and bacteriostatic effects. I

began to learn from the Indians about

their herbal remedies,' he says.

Unable to work in Canada as a doc-

tor he had to accept the role of hospital

orderly and from this unwanted per-

spective (4).

'I realised I had been completely

wrong in my approach. Like them I

had regarded my patients as objects I

UNIT 6

E Reading 2

Discussion

• Note down anything you

know about the causes of disease

and poor health in poor

countries.

• What is your opinion

regarding natural or herbal

medicines? Do you know of any

herbal preparations which

work?

• How far should one trust

doctors.

7

Reading exercises

1 At eight points in the article

you are going to read, sentences

or fragments have been

removed. What was in each

gap? Cover the list of sentences

and fragments at the end of the

article.

2 Study the list under the text,

which contains the missing

fragments from the article with

six additions. Choose the eight

correct items. Where do they

go in the article' Check with

your teacher and fill the gaps in

the text.

3 Mark the following statements

T (true) or F (false) according to

the article.

a Dr Carriconde is working in

London to find out if herbal

remedies such as lemon grass

really do work.

b People living around Kew

Gardens know about the

healing properties of herbs.

BRAZIL

68

UNIT 6

•Dr Carriconde believes that

doctors should stop providing

health.

Dr Carriconde wants people to

bow more about sickness and

what they can do to stay

healthy,

In Brazil, dangerous drugs are

sold indiscriminately.

In Canada, DrCarriconde took

the job of hospital orderly in

order to observe the doctors.

He was positively impressed by

the way the Canadian doctors

regarded patients.

h He and his wife went back to

Recife after elections in

Canada.

i An important aspect of Dr

Carriconde's scheme is that

people should have a sense of

community,

j Dr Carriconde just believes in

health and has no strong

political views.

4 Do you agree that 'the struggle

for health leads ultimately to

the doors of the rich and

powerful'? If not, why not? If

so, what can be done about it?

5 One could say that this article

and the Hemingway story in

Reading 1 contradict each

other. How?

6 Summarise the views of Dr

Carriconde in seven or eight

sentences.

had to heal. It induces people to

regard ill-health as something best

left to doctors. It induces fatalism.'

A change in government and an am-

nesty enabled Dr Carriconde and his

wife, Diana, to go home. (5)

The slum dwellers live in crowded,

narrow streets amid stinking fumes

from the sewage ducts and uncol-

lected piles of refuse, and having to

drink contaminated water.

'They had a half-remembered tra-

dition of herbal remedies, but thought

of disease as coming because God

willed it. For six months we just

learned from them and began to clas-

sify their use of herbs and the results.

They had empirical knowledge —

their herbal cures worked. They

didn't know why.'

With the assistance from Unais and

Christian Aid, 200 residents have

been trained as health workers in a

scheme designed to involve the people

and increase their confidence in their

own resources, and those of their

community.

'We would never start by saying

bronchitis is a disease of the lungs. We

would ask, in their own terminology,

how a mother treated her own chil-

dren for bronchitis.'

(6)

After the discussion, they are put in a

garden and the popular names, uses

and preparations are recorded.

'If a person doesn't have the appro-

priate curative herb in their own gar-

den they are referred to someone else

who does. The conversation likely to

arise stirs the social memory and

helps strengthen the community.'

(7)

—for 'TB or an infant with pneumonia

you have to use chemical drugs.' Nor

do they challenge the main cause of

disease — hunger. The struggle for

health leads them ultimately to the

well-secured doors of the rich and

powerful.

Anthony Swift The Sunday Times

a People bring plants to meetings.

b he studies such herbs.

C Because hygiene and natural

medicine do not cure all diseases

d which has flooded Brazil with drugs

(40,000 different varieties as opposed

to 7,000 in the UK)

e why a variety of mint, mixed with

honey, eradicates amoebas

f They went to Recife again to put into

practice what they had learned from

Canadian doctors.

g realised how ignorant primitive

people are about sickness.

h slum dwellers come to meetings with

the health workers.

i he observed his fellow doctors

j how modern drugs can cure their

diseases.

K But rubbish removal and herbal

remedies do not answer all diseases

I confirmed the curative properties of

honey

m the nature, cures, and causes of

disease.

n They went to Recife again to work

among the poor

69

UNIT 6

F Speaking

Focus on function: getting information tactfully;

giving opinions tactfully; giving advice and

making suggestions; accepting and refusing

advice; explaining problems; making excuses

1 Listening comprehension

Listen to the dialogue, and answer the following

questions.

a What information does Jack get out of Gladys?

b Why is Jack concerned?

c What does Jack suggest or advise?

d How does Gladys react?

2 Pronunciation

Listen to the ten utterances below, and mark the

syllables which carry main stress.

a Good Heavens, Gladys, you're getting really fat,

you know!

b Yes, perhaps I should.

c Do you mind if I ask how much you weigh these

days?

d How old are you, if you don't mind my asking?

e I really think you ought to lose weight.

f Well, I've tried that, but it's no good.

g It's all right for you, you're thin anyway!

h Look, Gladys, if you don't mind my saying so, I

think you're being rather negative.

i Have you tried doing exercises?

j You've got a point, I suppose. I'll try again.

Repeat each utterance, trying to match the

pronunciation on the cassette.

3 Reproduction

Using the flow diagram to help you, act out the

dialogue, using the original language where

possible, and improvising when necessary.

4 Improvisation

Improvise similar conversations for the following

problems.

A friend who drinks too much.

A friend who smokes too much.

The concerned friend should think first about what

advice to give. The person receiving the advice

should think about what the advice will be, and

think of excuses in advance.

BRITISH HEART FOUNDATION

Guide to a healthy heart

70