Mikkelsen A., Langhelle O. (eds.) Arctic Oil and Gas. Sustanability at Risk?

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

206 Ove Heitmann Hansen and Mette Ravn Midtgard

in total, with 485 million Sm

3

as liquid and 730 million Sm

3

as gas. This estimate

does not include the area of overlapping claims between Russia and Norway, a

disputed area. The uncertainty linked to this number is greater than that for the

rest of the NCS, where there has been more activity. There are higher expectations

of finding gas rather than oil in this area.

In Norway today, approximately 80,000 people are employed in the petroleum

sector. In 2005, the state’s net cash flow from the petroleum sector amounted to

approximately 33 per cent of total revenues. In 2005, crude oil, natural gas and

pipeline services accounted for 52 per cent of Norway’s exports in value terms.

Measured in Norwegian krone (NOK), the value of petroleum exports was 445

billion, 35 times higher than that of the export value of fish. The value of the

remaining petroleum reserves on the Norwegian Continental Shelf was estimated

at 4210 billion NOK in the National Budget for 2006.

Area with

overlapping

claims

Svalbard

Arctic area

Hammerfest

Harstad

Lofoten

Norway

Sweden

Finland

Russia

* Area excluded from year-round petroleum activities in light of the ULB (government report on impact on

Lofoten – Barents Sea of petroleum activities)

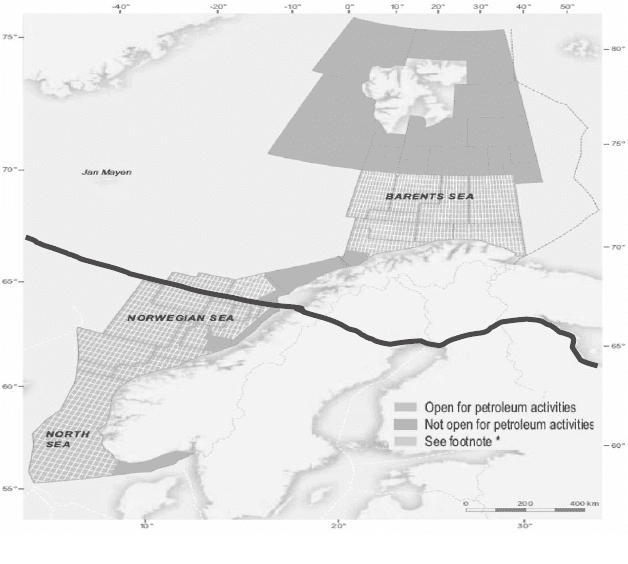

Map 9.1 Open and closed areas on the Norwegian Continental Shelf within the Arctic

area. (Source: Norwegian Petroleum Directorate.) *Area excluded from year-round

petroleum activities in light of the ULB (government report on the impact on the

Lofoten–Barents Sea of petroleum activities).

Activity in the Barents Sea Region

All Norwegian petroleum activity takes place offshore. Onshore reserves or reser-

voirs have not been identified and the probability of any reserves is regarded as

low. Exploration in the Barents Sea has yielded a number of discoveries. One proj-

ect is the Snøhvit gas field, northwest of Hammerfest, a city in the county of

Finnmark. The project is under construction and involves sub-sea-completed wells,

Textbox 9.3 The Barents Sea and Lofoten area

The Norwegian Continental Shelf (NCS) in the Barents Sea and outside

Lofoten constitutes two different geological territories (provinces). The

Barents Sea is shallow water with an average depth of 230 m. The Barents

Sea covers 7 per cent of the Arctic Ocean, yet the largest harvestable marine

resources of the Arctic are in this area. This is due to the fact that most of

the Northeast-Atlantic fish resources have part of or all their life cycle in

the Barents Sea. There are about 5.4 million nesting seabirds in the

Norwegian part of the Barents Sea, and most of these birds migrate south

in the winter.

The Shelf outside Lofoten

The Continental Shelf by Lofoten is geologically very narrow and, there-

fore, a limited area. Parts of the Shelf outside Lofoten (Nordland VI) were

opened for exploration in 1994, and one wildcat was drilled in 1999. The

assessed potential of this area is very high, and the source rock shows that

gas is most likely to be found. Also, oil is likely to be found in shallower

water. This area is temporary closed for oil and gas activity.

The Barents Sea Shelf

The Barents Sea Shelf is divided into many test-drilling areas, which vary

considerably and have very different geological histories. These areas have

had little or no investigation but some (the Hammerfest basin, the Tromsø

basin and parts of Lopphøgda) have been better explored. Parts of the

Tromsø basin were open for petroleum activity in 1979 and the first

permission for production was given in 1980. The Tromsø basin was

expanded in 1985, and the South Barents Sea was opened for exploration

in 1989. A total of 39 licence permissions have been granted in the Barents

Sea (2006), 64 wells have been drilled, and several small- and middle-sized

gas deposits have been discovered.

Source: Integrated Management plan for the Barents Sea.

Going North 207

208 Ove Heitmann Hansen and Mette Ravn Midtgard

a process plant for gas liquefaction (liquefied natural gas; LNG) and a closed

system for separating and re-injecting the carbon dioxide into the reservoir. The

field came on-stream in 2007. This is the first time Norway has signed agreements

to sell gas to markets outside of Europe. Another commercial oil field is Goliat,

where the production licence process will begin in 2007. Goliat will face serious

challenges due to the conflicting indigenous, social, environmental, biological and

fishing-related issues. Norwegian Hydro made the latest discovery in the Barents

Sea in an oil field called Nucula.

The first Integrated Management Plan in Norway

In 2002, the Norwegian parliament decided that the government should prepare an

Integrated Management Plan (IMP) for the Barents Sea. This decision, the follow-up

to the ‘Protecting the Riches of the Seas’ report,

4

resulted in the first comprehensive

management plan in Norway. The management plan should assess the considerations

related to the environment, the fishing industry, the petroleum industry and sea trans-

portation arising from increased activity in the Norwegian Arctic. Furthermore, the

plan states: ‘These plans must have sustainable development as a central objective,

and management of the ecosystems must be based on the precautionary principle

[World Commission on the Ethics of Scientific Knowledge and Technology, 2005]

and be implemented with respect for the limits that nature can tolerate’.

5

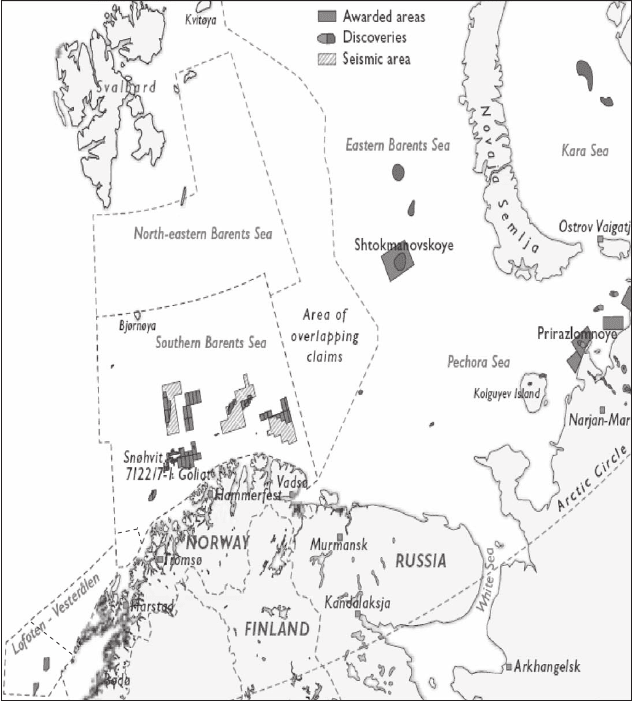

The IMP for the Barents Sea and the Lofoten area is the starting point for manage-

ment plans for other Norwegian Sea areas. The Storting approved the plan on March

31, 2006. As a result, the Lofoten area and the Northern Barents Sea remains closed

to petroleum activity, which includes the area around Bear Island, waters further

North, the Tromsø Patch and the edge of the pack ice (see Map 9.2). An additional

50-km wide zone from Troms II and east along the coast of Finnmark would also be

protected. The exceptions are where activity has already started and already

announced blocks in the area, which range from 35 to 50 km off the coast.

Oil production in Norway is expected to fall gradually after 2008. Gas produc-

tion is expected to increase until 2010. From representing around 30 per cent of

Norwegian petroleum production in 2005, gas production is likely to continue to

increase and may come to represent a share of more than 50 per cent by 2014.

The environmental aspect and arguments in the Arctic

petroleum debate

The Arctic region is characterized by its pristine nature and often regarded as the

frontier. A common assumption is that the Barents Sea is biologically vulnerable,

more vulnerable, but also cleaner than any other oceans. Although biological to

some degree, this impression of its nature is related to the traditional main

employer in the coastal areas, the fisheries. So far it is either the fear of harming

nature, or the lack of that fear, that involves people the most and generates the most

heated debates. Facts are uncertain; the problem has nothing to do with the discov-

ery of a particular fact, but with interpretation of a complex reality. And values are

in dispute; what is at stake is of huge importance to several stakeholders: the

costs, the benefits and so on. The IMP for the Barents Sea and Lofoten area iden-

tifies some areas as especially vulnerable. The physical, chemical and biological

characteristics vary from area to area, and one area is not equally vulnerable the

whole year round or to different types of impact. Therefore, many arguments in the

environmental debate have different perspectives, and often the stakeholders use

many different stories to underline their point of view.

Is the Arctic environment vulnerable or robust?

The concern for nature has been the most highlighted argument for not opening

the Norwegian Barents Sea to oil and gas exploitation. Scientists, to different

Nordland

Nordland

Troms II

Map 9.2 Norwegian and Russian parts of the Barents Sea.

Going North 209

210 Ove Heitmann Hansen and Mette Ravn Midtgard

degrees, claim that the environment is too fragile in the Barents Sea for this type

of economic activity. On the other side, this debate has many stakeholders, and

we find politicians, people in the petroleum industry and scientists who are scep-

tical of the vulnerability argument: They argue that there is no evidence for

excluding petroleum activity from the Barents Sea.

Environmental organizations are most emphatic about the vulnerability of the

environment in the Barents Sea and Lofoten area. They are all against oil and gas

activities in the Barents Sea and the Lofoten area, and claim that this region is

threatened by oil and gas and related activities. Both Bellona and the World Wildlife

Fund (WWF) Norway have chosen to emphasize the vulnerability of the Norwegian

Sea and the Barents Sea in the fight against oil and gas activities in the Arctic. In

fact, Bellona’s position is that there should be no oil and gas activity at all in the

Barents Sea and Lofoten area. They argue that oil activity represents a great threat

to natural and renewable resources in this region and that an oil spill incident will

result in very big losses for the ecosystems, as well as economic losses for the fish-

eries and aquaculture industry. Coldness, ice and sometimes extreme weather make

both oil activity and clean-up after an incident very difficult and risky.

The arguments about the Barents Sea as one of the world’s most important

ecological regions are taken further by the WWF, which has highlighted it as an

area with extraordinary biodiversity value, being the world’s highest density of

migratory seabirds, some of the richest fisheries in the world, diverse and rare

communities of sea mammals and the largest deep water coral reef in the world.

Oil and gas development may result in discharges of drilling chemicals, radioac-

tivity and produced water, and will certainly result in habitat destruction and

a risk of medium to large oil spills through blowouts, and pipeline leaks when

loading on to tankers or other accidents.

Oil spills in the sea ice, in polynyas or along the ice edge will have particu-

larly dramatic consequences. The existing response system and procedures

for dealing with oil spills are in this region of little effect, particularly in

rough weather.

6

The Norwegian Pollution Control Authority (SFT), the Institute of Marine

Research (IMR) and the Directorate of Fisheries are all warning against oil explo-

ration and extraction in the Arctic. This is because of the risk of accidents and the

lack of knowledge about the consequences resulting from spills. It is especially the

lack of knowledge that these institutions underline. SFT is concerned about

the large gap in knowledge about the effects of increased activity. The section of

the oil and gas industry in SFT has said: ‘The utmost care and precautions must

be taken in these matters. It is important for us to ensure that central parts of the

ecosystem are not damaged or that vulnerable resources are affected in a negative

way’.

7

The head of the IMR argues that the area is vulnerable because it is an

important spawning area for several fish species.

Other scientists have entered the debate and argued against the conception of

the Arctic as vulnerable and even argued against this premise. Four professors

from the University of Oslo wrote in the Norwegian newspaper, Aftenposten, in

2005: ‘The crude oil is a natural product, which is not especially dangerous to the

environment, and the Barents Sea is not particularly vulnerable compared to other

naval areas in the world’.

8

Their expertise is in biology and geology. The IMR

responded:

The professors give the impression that the ecology in the Barents Sea is

robust enough to stand oil extraction ... . Our knowledge indicates that the

ecosystems in the northern area are very easily affected by human activity

such as fisheries, military operations and also industrial activity on the

continent further south through long haul contamination.

9

The professors from Oslo argue that history has shown us that oil spills in

sensitive areas have not caused long-term environmental damage. They refer to

oil pollution from tankers or oil platforms in the last 30–40 years, which has been

very well studied. In particular, they studied the Exxon Valdez accident in Alaska

in 1989, when 37,000 tons of oil leaked from an oil tanker. They claim that after

one year or so, 90 per cent of the ordinary fauna and flora was back, and that inte-

grated studies in the last 15 years have further shown no negative impacts on the

salmon, sea lions, seals or sea birds.

An employee of the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate who shares the view of

a robust Barents Sea said:

The Arctic is constantly changing. Both nature and our planet are quite

robust, and the planet has faced several changes over time. The Barents Sea

is very robust and can handle discharge from crude oil. The ecological conse-

quences of oil and gas activities would be marginal.

10

This attitude is also common among oil companies, who refer to either ‘the

four professors’ or other official channels. Additionally, they often say that tech-

nology will provide solutions that will take care of the environment. A presenta-

tion from the Norwegian oil company Statoil stated: ‘technology will solve

environmental challenges’.

11

The oil company, ENI Norge, who discovered

the Goliat oil field in the Barents Sea, has stated: ‘Most biologists consider

the Barents Sea not to be a sensitive area; it is more politically rather than

biologically sensitive’.

12

Another oil company, BP, said:

It is possible to enter the Arctic today, there are no technological restrictions

against that ... . The challenges in the Arctic can be solved ... . There is a

lot of insecurity among people generally and politicians, but how much do

people outside the oil branch know about today’s possibilities for a safe

production? The big oil companies do not want to go into areas where the

environment can be threatened; this can have serious consequences for their

reputation.

13

Going North 211

212 Ove Heitmann Hansen and Mette Ravn Midtgard

The United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) warns against oil and gas

activity in the Norwegian Arctic area and is worried about the increasing pressure in

Norway for development of the Northern resources. Their Yearbook 2005 stated:

We know that the Arctic areas are very vulnerable, and the environment is

shifting constantly. We can see the climate changes around the Arctic and the

Antarctic. Oil and gas activity in the Arctic will be gambling, no matter how

strict the safety regulations are.

14

In the political landscape, we find opinions both supporting and not supporting

oil and gas activity; in between are those who are supportive, given severe precau-

tions and heavy restrictions. The right side of the political spectrum is generally

more positive to petroleum activity than the left. But all stakeholders, with their

different stories of the vulnerability of the area, emphasize that there are differences

between the Barents Sea and the area outside Lofoten. There are three drilling areas

outside of Lofoten that the discourse highlights: Nordland VI, VII and Troms II (see

Map 9.2). The Directorate of Fisheries recommends that neither exploration nor

extraction should be allowed in the area east of 400 m sea depth in Nordland VI, VII

and Troms II. Compared to other areas outside Norway, Greenpeace says that envi-

ronmental values at stake in the Barents Sea and Lofoten are quite different from

those in the Norwegian Sea, especially from a global perspective. The climate

is exposed and short, and simple food chains make this sea environment more

vulnerable to oil and chemical pollution than the more southern Norwegian Sea.

In a statement about the Integrated Management Plan, SFT said:

This area (Nordland VI, VII and Troms II – areas outside Lofoten) is of such

great value seen from an environmental- or business perspective that

currently any risk of damage is unacceptable. Therefore we have to consider

Petroleum-free zones.

15

Petroleum-free zones: the solution for co-existence

More stringent environmental requirements have been set in the later licence

rounds for areas considered more vulnerable. In addition, impact assessment

studies were initiated for petroleum recovery in the Barents Sea and in the area

off the Lofoten Islands before the seventeenth round. The discussion about

petroleum-free zones started in 2002 when Einar Steensnæs of the Christian

Party, the Norwegian Petroleum and Energy Minister at the time, said:

The impact study will give us a better basis for assessing continued opera-

tions in an area that is environmentally sensitive. Zero discharges form

a basic requirement here. Moreover, we shall consider establishing petro-

leum-free zones if it appears impossible to achieve co-existence between

petroleum and fishery activities.

16

The Chief Executive Officer of Hydro, Eivind Reiten, commented that there

was no doubt that petroleum-free zones would make it considerably more diffi-

cult to achieve the government’s goal of continued growth on the Norwegian shelf

up to 2050, as laid down in White Paper No. 38.

The debate about which areas should be protected and where the petroleum-

free zones should be returned to the forefront when the Soria Moria Declaration

of 2005 was presented. The environmental organizations, together with the Social

Left Party politicians, have been advocates for no petroleum activity in areas they

consider vulnerable. The WWF declared that it was the Social Left Party’s respon-

sibility to get petroleum-free zones incorporated into the Integrated Management

Plan. Greenpeace’s point of view was that there is no hurry to extract oil and gas,

but it is urgent to protect vulnerable areas. Furthermore, they said that these areas

should be kept free from oil and gas activity, and that the IMP should minimally

define some of the areas as permanent, petroleum-free zones. Bellona said that

the only way to keep areas closed to petroleum activity was to establish petro-

leum-free zones, and that ‘by giving the vulnerable areas outside Lofoten and the

Barents Sea the status of petroleum-free zones, some of the world’s most unique

areas could be secured for the future’.

17

Politicians in the Socialist Left Party and the Central Party also fear that, if oil

companies discover oil in the Barents Sea, it will be next to impossible to deny

exploitation. They and the environmental non-governmental organizations

(NGOs) consider the only solution to this potential situation is to establish petro-

leum-free zones.

The environmental groupings were disappointed when the IMP did not define

any petroleum-free zones in the Barents Sea. The arguments and accusations were

at times very heated and culminated when a draft of the IMP was accidentally

presented on a stakeholder’s web page while the plan was still under hearing. The

Norwegian Oil Industry Association (OLF), an influent stakeholder for increased

activity, commented: ‘No petroleum-free zones. Perhaps most surprising in the

draft of the Integrated Management Plan is that the government is avoiding the

term “petroleum-free zones” about the areas that shall have special assessment’.

18

The Integrated Management Plan was presented to the parliament on March

31, 2006 and there was still an absence of terms such as ‘petroleum-free zones’

in the official version. The IMP provided a temporary protection of the area

outside Lofoten and Vesterålen (Nordland VI, Nordland VII and Troms II). In

addition there would be a 50-km wide zone from Troms II and east along the coast

of Finnmark that would be protected. The exceptions were where activity had

already started and where there were blocks already announced in the area, which

ranged from 35 to 50 km off the coast. Therefore, the Goliat project was allowed

to continue. At the presentation of the IMP, the Environment Minister said it was

a balanced compromise. She also said it would be updated in 2010 based on the

knowledge gained in the meantime.

It was important to the environmental organizations that the other parties in

parliament supported this temporary protection. This assured them that protection

could last longer than just the course of this parliamentary period but, in any case,

Going North 213

214 Ove Heitmann Hansen and Mette Ravn Midtgard

the debate will surface again in 2009. Regardless of the result, Friends of the

Earth will fight to reduce the activity in the North; they will say that a temporary

solution is better than nothing. On their homepage we can read:

It is the fourth time we have managed to keep the platform away from

Lofoten and Vesterålen. Although no area was granted permanent protection

this time, we know that professional environmental consultations have

concluded time after time that these fields cannot withstand oil and gas

drilling. Sooner or later the Storting and the Government must listen to their

own professional departments.

19

The WWF’s opinion is that petroleum-free zones are the only solution for safe-

guarding the 45,000 working places, which depend upon a clean and productive

ocean. Furthermore, they say that petroleum-free zones are not a direct cost, but

an insurance that Norway must afford to secure working places for its Northern

population and as an area of world-class nature.

The climatic influence: from local to global

Offshore oil and gas activities entail considerable outputs of gases into the atmos-

phere from power generation, flaring, well testing, leakage of volatile petroleum

components, supply activities and shuttle transportation. Air emissions have

effects on the climate. OLF says that the oil and gas industry is willing to buy the

quotas needed for Norway to fulfil its climate commitments. At the same time,

the industry wants to allocate funds for environmental measures. The environ-

mental organizations and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

are present in the debate over the role of oil and gas due to climate change. The

UN has concluded that: ‘Increased commercial pressures on the Polar regions

bring with them increased threats to the ecosystems and, in the Arctic, increased

challenges for the sustainability of local economies and ways of life’.

20

UNEP

especially warns against oil drilling in the Barents Sea, as it considers the Arctic

areas to be extremely vulnerable to rapid climate change.

The debate about the effects of oil and gas activity on climate change is

primarily based on global concerns. More oil and gas activity will not reduce

CO

2

emissions; therefore, Norway will have problems with reaching its emission

reduction targets. Research is showing that the sea ice in the Arctic, with a

doubling of the CO

2

discharges, may not only completely disappear in the

summer by 2050, but may also be reduced by 20 per cent in the winter. Under this

scenario, the whole Barents Sea would be ice-free in the winter. More stormy

weather along the coast would present major negative consequences for sea trans-

portation, oil and gas activities, coastal fishing and fishery and the inhabitants of

the coast. The ice in the Barents Sea will be pushed North and East because of

increasing Southwestern winds and warmer weather. This will expand the fishing

area and possibly make it easier for the oil and gas industry to operate in the

winter in a larger part of the Arctic, raising new geopolitical questions.

In 2004, the WWF said they were very disappointed with the Norwegian

Foreign Minister, Jan Petersen, from the Conservative Party, who had not taken

the opportunity to promise new cuts in CO

2

emissions after the first Kyoto period.

Bellona is also using the climate argument to stop oil and gas activity in the

Barents Sea and Lofoten area, saying: ‘It should not be possible to open up the

Barents Sea for exploration because of the climate- and environmental changes’.

21

Bellona claims that the Barents Sea should not be open for exploration owing to

climate–environmental changes, as this would lead to it becoming an even more

exposed area than earlier assumed. Evidence of accelerating climate change in the

Barents Sea and Lofoten area, including notable shrinking of the Arctic sea ice,

continues to accumulate, while current and planned expansion of commercial

exploitation in both regions has raised concerns for sustainability. Bellona says

that oil and gas activity in the Barents Sea and Lofoten area could raise the

Norwegian CO

2

emissions by 8 per cent. The government says that the establishment

of a CO

2

value chain is high on their agenda, and they are using this to potentially

further increase oil recovery, which would contribute towards Norway meeting its

international commitments concerning greenhouse gas emissions. But will this

extra oil recovery cause more CO

2

from the used oil at the same time?

Another issue in the Arctic is that these climate changes will bring more and

heavier storms, which again may result in erosion of coastal areas and invasions

of new species to a biological environment that has been protected previously by

stable frost. New invading animals may bring new diseases to the area.

Researchers also fear that CO

2

and methane contained in the permafrost and seas

would be released to the atmosphere as a result of melting ice and a warmer sea.

Changes in the climate in the Arctic area could have important effects on the

climate in other parts of the world too. But a warmer Arctic will also have posi-

tive effects regionally, as greater possibilities for sea transportation, enlarged

fisheries and increased petroleum activities in and around Spitsbergen.

It’s our turn now

The inhabitants in Northern Norway have been optimistic and positive at several

stages during the debate about petroleum development in the province. The last

time the petroleum companies operated in the Barents Sea was in 1993, but they

soon left when they found no oil, and they considered the rather small gas discov-

eries not profitable enough for exploration. Since then, new technology solutions

and market demands (delivery security and price) have made the Barents Sea area

noteworthy again. Statoil were given permission to start constructing the Snøhvit

LNG plant in Hammerfest in 2002, and production started in 2007. This gas field

has meant the start of a prosperous petroleum age in the Arctic Norway. ENI

Norge discovered far more oil in the Goliat field in 2005 than anticipated, which

was another major step forwards for further oil activity in the Barents Sea.

The gas project Snøhvit, the Goliat plans, the postponed giant gas field

Shtokman on the Russian side and the Soria Moria Declaration have once again

caused optimism in the North. This time, at least, construction work is under way

Going North 215