McConnell С., Campbell R. Macroeconomics: principles, problems, and policies, 17th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PART SIX

International Economics

374

based on supply and demand in the foreign exchange mar-

ket. They recognize that changing economic conditions

among nations require continuing changes in equilibrium

exchange rates to avoid persistent payments deficits or

surpluses. They rely on freely operating foreign exchange

markets to accomplish the necessary adjustments. The re-

sult has been considerably more volatile exchange rates

than those during the Bretton Woods era.

But nations also recognize that certain trends in the

movement of equilibrium exchange rates may be at odds

with national or international objectives. On occasion, na-

tions therefore intervene in the foreign exchange market

by buying or selling large amounts of specific currencies.

This way, they can “manage” or stabilize exchange rates

by influencing currency demand and supply.

The leaders of the G8 nations (Canada, France, Germany,

Italy, Japan, Russia, United Kingdom, and United States)

meet regularly to discuss economic issues and try to coordi-

nate economic policies. At times they have collectively inter-

vened to try to stabilize currencies. For example, in 2000

they sold dollars and bought euros in an effort to stabilize

the falling value of the euro relative to the dollar. In the pre-

vious year the euro (

) had depreciated from 1 ⫽ $1.17 to

1 ⫽ $.87.

The current exchange-rate system is thus an “almost”

flexible exchange-rate system. The “almost” refers mainly

to the periodic currency interventions by governments; it

also refers to the fact that the actual system is more com-

plicated than described. While the major currencies such

as dollars, euros, pounds, and yen fluctuate in response to

changing supply and demand, some developing nations

peg their currencies to the dollar and allow their curren-

cies to fluctuate with it against other currencies. Also,

some nations peg the value of their currencies to a “basket”

or group of other currencies.

How well has the managed float worked? It has both

proponents and critics.

In Support of the Managed Float Proponents

of the managed-float system argue that is has functioned

far better than many experts anticipated. Skeptics had

predicted that fluctuating exchange rates would reduce

world trade and finance. But in real terms world trade un-

der the managed float has grown tremendously over the

past several decades. Moreover, as supporters are quick to

point out, currency crises such as those in Mexico and

southeast Asia in the last half of the 1990s were not the

result of the floating-exchange-rate system itself. Rather,

the abrupt currency devaluations and depreciations re-

sulted from internal problems in those nations, in con-

junction with the nations’ tendency to peg their currencies

to the dollar or to a basket of currencies. In some cases,

flexible exchange rates would have made these adjust-

ments far more gradual.

Proponents also point out that the managed float has

weathered severe economic turbulence that might have

caused a fixed-rate system to break down. Such events as

extraordinary oil price increases in 1973–1974 and again

in 1981–1983, inflationary recessions in several nations in

the mid-1970s, major national recessions in the early

1980s, and large U.S. budget deficits in the 1980s and the

first half of the 1990s all caused substantial imbalances in

international trade and finance, as did the large U.S. bud-

get deficits and soaring world oil prices that occurred in

the middle of the first decade of the 2000s. Flexible rates

enabled the system to adjust to all these events, whereas

the same events would have put unbearable pressures on a

fixed-rate system.

Concerns with the Managed Float There is

still much sentiment in favor of greater exchange-rate sta-

bility. Those favoring more stable exchange rates see

problems with the current system. They argue that the ex-

cessive volatility of exchange rates under the managed

float threatens the prosperity of economies that rely heav-

ily on exports. Several financial crises in individual nations

(for example, Mexico, South Korea, Indonesia, Thailand,

Russia, and Brazil) have resulted from abrupt changes in

exchange rates. These crises have led to massive “bailouts”

of those economies via IMF loans. The IMF bailouts, in

turn, may encourage nations to undertake risky and inap-

propriate economic policies since they know that, if need

be, the IMF will come to the rescue. Moreover, some ex-

change-rate volatility has occurred even when underlying

economic and financial conditions were relatively stable,

suggesting that speculation plays too large a role in deter-

mining exchange rates.

Perhaps more important, assert the critics, the man-

aged float has not eliminated trade imbalances, as flexible

rates are supposed to do. Thus, the United States has run

persistent trade deficits for many years, while Japan has

run persistent surpluses. Changes in exchange rates be-

tween dollars and yen have not yet corrected these imbal-

ances, as is supposed to be the case under flexible exchange

rates.

Skeptics say the managed float is basically a “nonsys-

tem”; the guidelines concerning what each nation may or

may not do with its exchange rates are not specific enough

to keep the system working in the long run. Nations in-

evitably will be tempted to intervene in the foreign ex-

change market, not merely to smooth out short-term

fluctuations in exchange rates but to prop up their currency

if it is chronically weak or to manipulate the exchange rate

to achieve domestic stabilization goals.

mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 374mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 374 9/15/06 3:31:58 PM9/15/06 3:31:58 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 19

Exchange Rates, the Balance of Payments, and Trade Deficits

375

So what are we to conclude? Flexible exchange rates

have not worked perfectly, but they have not failed miser-

ably. Thus far they have survived, and no doubt have eased,

several major shocks to the international trading system.

Meanwhile, the “managed” part of the float has given na-

tions some sense of control over their collective economic

destinies. On balance, most economists favor continuation

of the present system of “almost” flexible exchange rates.

2005). The United States is China’s largest export market,

and although China has increased its imports from the

United States, its standard of living has not yet increased

enough for its citizens to afford large quantities of U.S.

goods and services. Adding to the problem, China has fixed

the exchange rate of it currency, the yuan, to a basket of

currencies that includes the dollar. Therefore its large trade

surplus with the United States has not caused the yuan to

QUICK REVIEW 19.3

• Under the gold standard (1879–1934), nations fixed

exchange rates by valuing their currencies in terms of gold,

by tying their stocks of money to gold, and by allowing gold

to flow between nations when balance-of-payments deficits

and surpluses occurred.

• The Bretton Woods exchange-rate system (1944–1971) fixed

or pegged exchange rates but permitted orderly adjustments

of the pegs under special circumstances.

• The managed floating system of exchange rates (1971–

present) relies on foreign exchange markets to establish

equilibrium exchange rates. The system permits nations to

buy and sell foreign currency to stabilize short-term changes

in exchange rates or to correct exchange-rate imbalances that

are negatively affecting the world economy.

Recent U.S. Trade Deficits

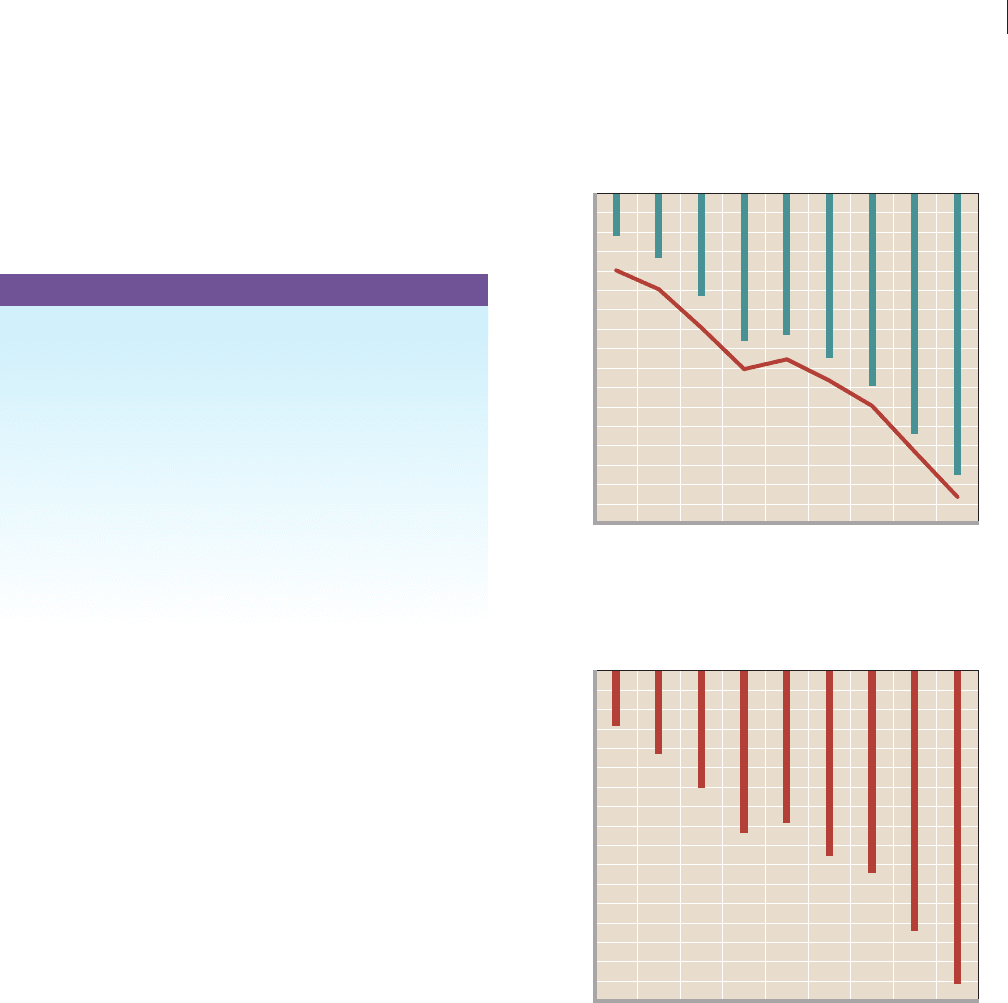

As indicated in Figure 19.3a , the United States has experi-

enced large and persistent trade deficits over the past sev-

eral years. These deficits climbed steadily between 1997

and 2000, fell slightly in the recessionary year 2001, and

rose sharply between 2002 and 2005. In 2005 the trade

deficit on goods was $782 billion and the trade deficit on

goods and services was $724 billion. The current account

deficit ( Figure 19.3b ) reached a record $805 billion in 2005.

It rose from 5.7 percent of GDP in 2004 to 6.4 percent of

GDP in 2005. Large trade deficits are expected to continue

for many years, both in absolute and relative terms.

Causes of the Trade Deficits

Several reasons account for these large trade deficits. First,

between 1997 and 2000, and again between 2003 and

2005, the U.S. economy grew more rapidly than the econ-

omies of several of its major trading partners. That strong

growth of U.S. income enabled Americans to buy more

imported goods. In contrast, Japan and some European

nations either suffered recession or experienced slower in-

come growth. So their purchases of U.S. exports did not

keep pace with the growing U.S. imports.

Also, large trade deficits with China have emerged,

reaching $202 billion in 2005. This amount is even greater

than the U.S. trade imbalance with Japan ($83 billion in

FIGURE 19.3 U.S. trade deficits, 1994–2005. (a) The

United States experienced large deficits in goods and in goods and services

between 1997 and 2005. (b) The U.S. current account, generally reflecting

the goods and services deficit, was also in substantial deficit. These trade

deficits are expected to continue throughout the current decade.

(a)

Balance of trade

Billions of Dollars

(b)

Balance on current account

Billions of Dollars

–850

–800

–750

–700

–650

–600

–550

–500

–450

–400

–350

–300

–250

–200

–150

–100

–50

0

200520042003200220012000199919981997

–850

–800

–750

–700

–650

–600

–550

–500

–450

–400

–350

–300

–250

–200

–150

–100

–50

0

200520042003200220012000199919981997

Goods

Goods and Services

mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 375mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 375 9/15/06 7:16:33 PM9/15/06 7:16:33 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART SIX

International Economics

376

appreciate in value relative to the U.S. dollar. That appre-

ciation would make Chinese goods more expensive in the

United States and reduce U.S. imports of Chinese goods.

In China a stronger yuan would reduce the dollar price of

U.S. goods and increase Chinese purchases of U.S. exports.

Reduced U.S. imports from China and increased U.S. ex-

ports to China would reduce the large U.S. trade deficit.

Another factor causing the large U.S. trade deficits

has been the rapid rise of the price of oil. Because the

United States imports a large percentage of its oil, rising

prices tend to aggravate trade deficits. For example, in

2005 the United States had a $94 billion trade deficit with

the OPEC countries.

Finally, a declining U.S. saving rate (⫽ saving兾total in-

come) has also contributed to U.S. trade deficits. In recent

years, the saving rate has declined while the investment

rate (⫽ investment/total income) has remained stable or

even increased. The gap has been met through foreign

purchases of U.S. real and financial assets, creating a large

capital and financial account surplus. Because foreign sav-

ers are willingly financing a larger part of U.S. investment,

Americans are able to save less than otherwise and con-

sume more. Part of that added consumption spending is on

imported goods. Also, many foreigners view U.S. real as-

sets favorably because of the relatively high risk-adjusted

rates of return they generate. The purchase of those assets

provides foreign currency to Americans to finance their

strong appetite for imported goods.

The point is that the capital account surplus may be a

partial cause of the trade deficits, not just a result of those

deficits.

Implications of U.S. Trade Deficits

The recent U.S. trade deficits are the largest ever run by a

major industrial nation. Whether the large trade deficits

should be of significant concern to the United States and

Last

Word

Speculation in Currency Markets

Are Speculators a Negative or a Positive Influence

in Currency Markets and International Trade?

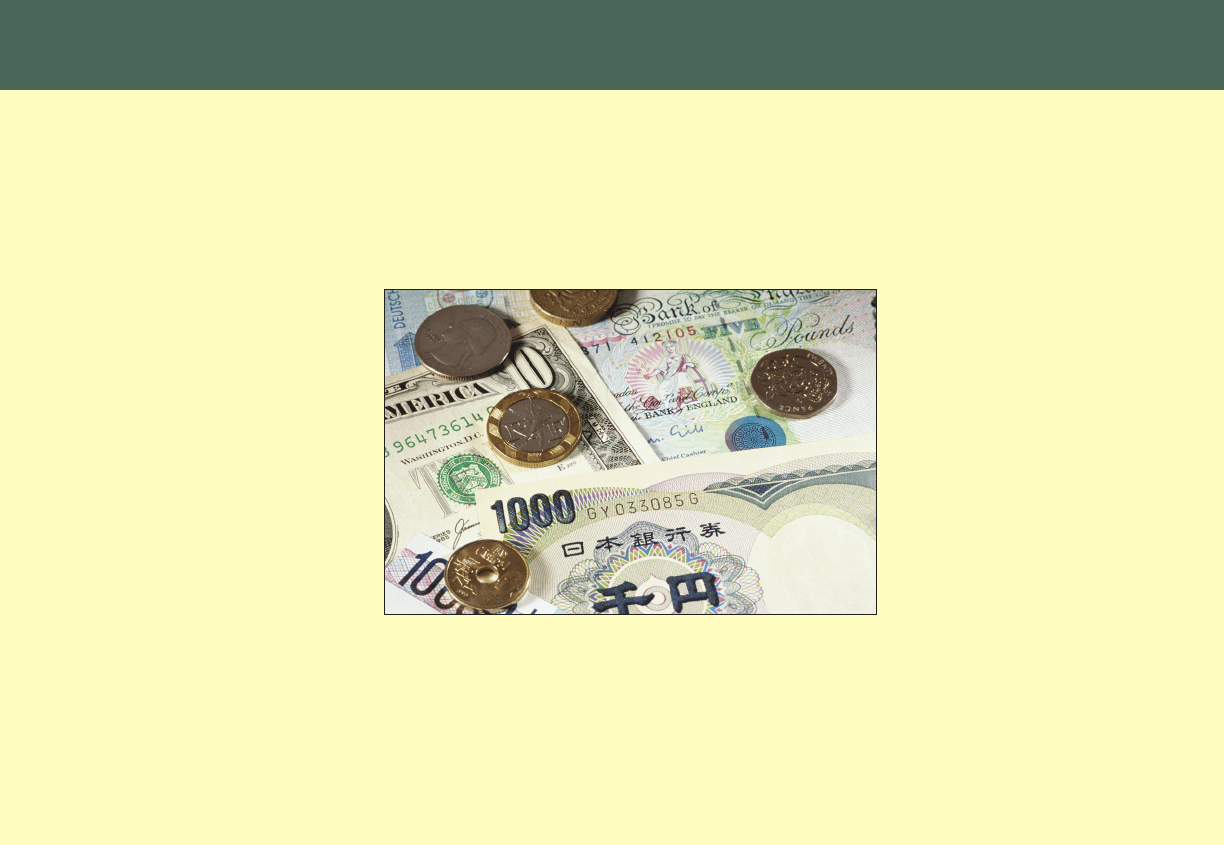

Most people buy foreign currency to facilitate the purchase of

goods or services from another country. A U.S. importer buys

Japanese yen to purchase Japanese autos. A Hong Kong

financial investor purchases Australian dollars to invest in the

Australian stock market. But there is another group of partici-

pants in the currency market—speculators—that buys and sells

foreign currencies in the hope of reselling or rebuying them

later at a profit.

Contributing to Exchange-Rate Fluctuations Speculators

were much in the news in late 1997 and 1998 when they were

widely accused of driving down the values of the South Korean

won, Thailand baht, Malaysian ringgit, and Indonesian rupiah.

The value of these currencies fell by as much as 50 percent

within 1 month, and speculators undoubtedly contributed to the

swiftness of those declines. The expectation of currency depre-

ciation (or appreciation) can be self-fulfilling. If speculators, for

example, expect the Indonesian rupiah to be devalued or to de-

preciate, they quickly sell rupiah and buy currencies that they

think will increase in relative value. The sharp increase in the

supply of rupiah indeed reduces its value; this reduction then

may trigger further selling of rupiah in expectation of further

declines in its value.

But changed economic realities, not speculation, are nor-

mally the underlying causes of changes in currency values. That

was largely the case with the southeast Asian countries in which

actual and threatened bankruptcies in the financial and manu-

facturing sectors undermined confidence in the strength of the

currencies. Anticipating the eventual declines in currency val-

ues, speculators simply hastened those declines. That is, the de-

clines in value probably would have occurred with or without

speculators.

Moreover, on a daily basis, speculation clearly has positive

effects in foreign exchange markets.

Smoothing Out Short-Term Fluctuations in Currency

Prices When temporarily weak demand or strong supply re-

duces a currency’s value, speculators quickly buy the currency,

adding to its demand and strengthening its value. When tempo-

rarily strong demand or weak supply increases a currency’s

value, speculators sell the currency. That selling increases the

supply of the currency and reduces its value. In this way specu-

lators smooth out supply and demand, and thus exchange rates,

over short time periods. This day-to-day exchange-rate stabili-

zation aids international trade.

Absorbing Risk Speculators also absorb risk that others do not

want to bear. Because of potential adverse changes in exchange

rates, international transactions are riskier than domestic trans-

376

mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 376mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 376 9/15/06 3:31:58 PM9/15/06 3:31:58 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 19

Exchange Rates, the Balance of Payments, and Trade Deficits

377

377

FPO

actions. Suppose AnyTime, a hypothetical retailer, signs a con-

tract with a Swiss manufacturer to buy 10,000 Swatch watches

to be delivered in 3 months. The stipulated price is 75 Swiss

francs per watch, which in dollars is $50 per watch at the pres-

ent exchange rate of, say, $1 ⫽ 1.5 francs. AnyTime’s total bill

for the 10,000 watches will be $500,000 (⫽ 750,000 francs).

But if the Swiss franc were to appreciate, say, to $1 ⫽ 1

franc, the dollar price per

watch would rise from $50 to

$75 and AnyTime would

owe $750,000 for the watches

(⫽ 750,000 francs). AnyTime

may reduce the risk of such an

unfavorable exchange-rate fluc-

tuation by hedging in the fu-

tures market. Hedging is an

action by a buyer or a seller to

protect against a change in fu-

ture prices. The futures market

is a market in which currencies

are bought and sold at prices

fixed now, for delivery at a

specified date in the future.

AnyTime can purchase the needed 750,000 francs at

the current $1 ⫽ 1.5 francs exchange rate, but with delivery in

3 months when the Swiss watches are delivered. And here is

where speculators come in. For a price determined in the

futures market, they agree to deliver the 750,000 francs to

AnyTime in 3 months at the $1 ⫽ 1.5 francs exchange rate,

regardless of the exchange rate then. The speculators need not

own francs when the agreement is made. If the Swiss franc de-

preciates to, say, $1 ⫽ 2 francs in this period, the speculators

profit. They can buy the 750,000 francs stipulated in the con-

tract for $375,000, pocketing the difference between that

amount and the $500,000 AnyTime has agreed to pay for the

750,000 francs. If the Swiss franc appreciates, the speculators,

but not AnyTime, suffer a loss.

The amount AnyTime

must pay for this “exchange-

rate insurance” will depend on

how the market views the like-

lihood of the franc depreciat-

ing, appreciating, or staying

constant over the 3-month pe-

riod. As in all competitive mar-

kets, supply and demand

determine the price of the fu-

tures contract.

The futures market thus

eliminates much of the ex-

change-rate risk associated with

buying foreign goods for future

delivery. Without it, AnyTime might have decided against im-

porting Swiss watches. But the futures market and currency

speculators greatly increase the likelihood that the transaction

will occur. Operating through the futures market, speculation

promotes international trade.

In short, although speculators in currency markets occa-

sionally contribute to swings in exchange rates, on a day-to-day

basis they play a positive role in currency markets.

the rest of the world is debatable. Most economists see

both benefits and costs to trade deficits.

Increased Current Consumption At the time

a trade deficit or a current account deficit is occurring,

American consumers benefit. A trade deficit means that

the United States is receiving more goods and services as

imports from abroad than it is sending out as exports.

Taken alone, a trade deficit allows the United States to

consume outside its production possibilities curve. It aug-

ments the domestic standard of living. But here is a catch:

The gain in present consumption may come at the expense

of reduced future consumption. When and if the current

account deficit declines, Americans may have to consume

less than before and perhaps even less than they produce.

Increased U.S. Indebtedness A trade deficit is

considered unfavorable because it must be financed by

borrowing from the rest of the world, selling off assets, or

dipping into official reserves. Recall that current account

deficits are financed primarily by net inpayments of for-

eign currencies to the United States. When U.S. exports

are insufficient to finance U.S. imports, the United States

increases both its debt to people abroad and the value of

foreign claims against assets in the United States. Financ-

ing of the U.S. trade deficit has resulted in a larger for-

eign accumulation of claims against U.S. financial and

real assets than the U.S. claim against foreign assets. To-

day, the United States is the world’s largest debtor nation.

In 2004 foreigners owned $2.5 billion more of U.S. assets

(corporations, land, stocks, bonds, loan notes) than U.S.

citizens and institutions owned in foreign assets.

If the United States wants to regain ownership of

these domestic assets, at some future time it will have to

export more than it imports. At that time, domestic con-

sumption will be lower because the United States will

need to send more of its output abroad than it receives as

mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 377mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 377 9/15/06 3:31:59 PM9/15/06 3:31:59 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART SIX

International Economics

378

imports. Therefore, the current consumption gains deliv-

ered by U.S. current account deficits may mean perma-

nent debt, permanent foreign ownership, or large sacrifices

of future consumption.

We say “may mean” above because the foreign lend-

ing to U.S. firms and foreign investment in the United

States increases the U.S. capital stock. U.S. production ca-

pacity therefore might increase more rapidly than other-

wise because of a large surplus on the capital and financial

account. Faster increases in production capacity and real

GDP enhance the economy’s ability to service foreign

debt and buy back real capital, if that is desired.

In short, trade deficits are a mixed blessing. The

long-term impacts of the record-high U.S. trade deficits

are largely unknown. That “unknown” worries some

economists, who are concerned that foreigners will

lose financial confidence in the United States. If that

happens, they would restrict their lending to American

households and businesses and also reduce their pur-

chases of U.S. assets. Both actions would decrease the

demand for U.S. dollars in the foreign exchange market

and cause the U.S. dollar to depreciate. A sudden, large

depreciation of the U.S. dollar might disrupt world trade

and negatively affect economic growth worldwide. Other

economists, however, downplay this scenario. Because

any decline in the U.S. capital and financial account

surplus is automatically met with a decline in the current

account deficit, the overall impact on the American econ-

omy would be slight.

Summary

1. U.S. exports create a foreign demand for dollars and make a

supply of foreign exchange available to the United States.

Conversely, U.S. imports create a demand for foreign ex-

change and make a supply of dollars available to foreigners.

Generally, a nation’s exports earn the foreign currencies

needed to pay for its imports.

2. The balance of payments records all international trade and

financial transactions taking place between a given nation

and the rest of the world. The balance on goods and services

(the trade balance) compares exports and imports of both

goods and services. The current account balance includes

not only goods and services transactions but also net invest-

ment income and net transfers.

3. The capital and financial account includes (a) the net

amount of the nation’s debt forgiveness and (b) the nation’s

sale of real and financial assets to people living abroad less

its purchases of real and financial assets from foreigners.

4. The current account and the capital and financial account

always sum to zero. A deficit in the current account is al-

ways offset by a surplus in the capital and financial account.

Conversely, a surplus in the current account is always offset

by a deficit in the capital and financial account.

5. A balance-of-payments deficit is said to occur when a nation

must draw down its official reserves, making inpayments

to its balance of payments, in order to balance the capital

and financial account with the current account. A balance-

of-payments surplus occurs when a nation must increase its

official reserves, making outpayments from its balance of

payments, to balance the two accounts. The desirability of a

balance-of-payments deficit or surplus depends on its size

and its persistence.

6. Flexible or floating exchange rates between international

currencies are determined by the demand for and supply of

those currencies. Under flexible rates a currency will depre-

ciate or appreciate as a result of changes in tastes, relative

income changes, relative price changes, relative changes in

real interest rates, and speculation.

7. The maintenance of fixed exchange rates requires adequate

reserves to accommodate periodic payments deficits. If re-

serves are inadequate, nations must invoke protectionist

trade policies, engage in exchange controls, or endure unde-

sirable domestic macroeconomic adjustments.

8. The gold standard, a fixed-rate system, provided exchange-

rate stability until its disintegration during the 1930s. Un-

der this system, gold flows between nations precipitated

sometimes painful changes in price, income, and employ-

ment levels in bringing about international equilibrium.

9. Under the Bretton Woods system, exchange rates were

pegged to one another and were stable. Participating na-

tions were obligated to maintain these rates by using stabili-

zation funds, gold, or loans from the IMF. Persistent or

“fundamental” payments deficits could be resolved by IMF-

sanctioned currency devaluations.

10. Since 1971 the world’s major nations have used a system of

managed floating exchange rates. Market forces generally

set rates, although governments intervene with varying fre-

quency to alter their exchange rates.

11. Between 1997 and 2005, the United States had large and

rising trade deficits, which are projected to last well into the

future. Causes of the trade deficits include (a) more rapid

income growth in the United States than in Japan and some

European nations, resulting in expanding U.S. imports rela-

tive to exports, (b) the emergence of a large trade deficit

mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 378mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 378 9/15/06 3:32:00 PM9/15/06 3:32:00 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 19

Exchange Rates, the Balance of Payments, and Trade Deficits

379

with China, (c) rising prices of imported oil, and (d) a large

surplus in the capital and financial account, which enabled

Americans to reduce their saving and buy more imports.

12. U.S. trade deficits have produced current increases in the

living standards of U.S. consumers. The accompanying sur-

Study Questions

pluses on the capital and financial account have increased

U.S. debt to the rest of the world and increased foreign

ownership of assets in the United States. This greater for-

eign investment in the United States, however, has undoubt-

edly increased U.S. production possibilities.

Terms and Concepts

balance of payments

current account

balance on goods and

services

trade deficit

trade surplus

balance on current account

capital and financial account

balance on capital and

financial account

balance-of-payments

deficits and surpluses

official reserves

flexible- or floating-

exchange-rate system

fixed-exchange-rate system

purchasing-power-parity

theory

currency interventions

exchange controls

gold standard

devaluation

Bretton Woods system

International Monetary

Fund (IMF)

managed floating exchange

rates

1. Explain how a U.S. automobile importer might finance a

shipment of Toyotas from Japan. Trace the steps as to how a

U.S. export of machinery to Italy might be financed. Ex-

plain: “U.S. exports earn supplies of foreign currencies that

Americans can use to finance imports.”

2.

KEY QUESTION Indicate whether each of the following cre-

ates a demand for or a supply of European euros in foreign

exchange markets:

a. A U.S. airline firm purchases several Airbus planes as-

sembled in France.

b. A German automobile firm decides to build an assembly

plant in South Carolina.

c. A U.S. college student decides to spend a year studying

at the Sorbonne in Paris.

d. An Italian manufacturer ships machinery from one

Italian port to another on a Liberian freighter.

e. The U.S. economy grows faster than the French

economy.

f. A U.S. government bond held by a Spanish citizen ma-

tures, and the loan amount is paid back to that person.

g. It is widely believed that the euro will depreciate in the

near future.

3.

KEY QUESTION Alpha’s balance-of-payments data for 2006

are shown below. All figures are in billions of dollars. What

are the ( a ) balance on goods, ( b ) balance on goods and ser-

vices, ( c ) balance on current account, and ( d ) balance on

capital and financial account? Suppose Alpha needed to de-

posit $10 billion of official reserves into the capital and fi-

nancial account to balance it against the current account.

Does Alpha have a balance-of-payments deficit or surplus?

Explain.

4. China had a $150 billion overall current account surplus in

2005. Assuming that China’s net debt forgiveness was zero

in 2005 (its capital account balance was zero), what can you

specifically conclude about the relationship of Chinese pur-

chases of financial and real assets abroad versus foreign pur-

chases of Chinese financial and real assets? Explain.

5. “A rise in the dollar price of yen necessarily means a fall in

the yen price of dollars.” Do you agree? Illustrate and elab-

orate: “The critical thing about exchange rates is that they

provide a direct link between the prices of goods and ser-

vices produced in all trading nations of the world.” Explain

the purchasing-power-parity theory of exchange rates.

6. Suppose that a Swiss watchmaker imports watch compo-

nents from Sweden and exports watches to the United

States. Also suppose the dollar depreciates, and the Swedish

krona appreciates, relative to the Swiss franc. Speculate as to

how each would hurt the Swiss watchmaker.

7.

KEY QUESTION Explain why the U.S. demand for Mexican

pesos is downward-sloping and the supply of pesos to

Goods exports ⫹$40

Goods imports ⫺30

Service exports ⫹15

Service imports ⫺10

Net investment income ⫺5

Net transfers ⫹10

Balance on capital account 0

Foreign purchases of Alpha assets ⫹20

Alpha purchases of assets abroad ⫺40

mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 379mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 379 9/15/06 3:32:00 PM9/15/06 3:32:00 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART SIX

International Economics

380

Americans is upward-sloping. Assuming a system of flexible

exchange rates between Mexico and the United States, indi-

cate whether each of the following would cause the Mexican

peso to appreciate or depreciate:

a. The United States unilaterally reduces tariffs on

Mexican products.

b. Mexico encounters severe inflation.

c. Deteriorating political relations reduce American tour-

ism in Mexico.

d. The U.S. economy moves into a severe recession.

e. The United States engages in a high-interest-rate mon-

etary policy.

f. Mexican products become more fashionable to U.S.

consumers.

g. The Mexican government encourages U.S. firms to

invest in Mexican oil fields.

h. The rate of productivity growth in the United States

diminishes sharply.

8. Explain why you agree or disagree with the following state-

ments:

a. A country that grows faster than its major trading part-

ners can expect the international value of its currency to

depreciate.

b. A nation whose interest rate is rising more rapidly than

interest rates in other nations can expect the interna-

tional value of its currency to appreciate.

c. A country’s currency will appreciate if its inflation rate

is less than that of the rest of the world.

9. “Exports pay for imports. Yet in 2005 the nations of the

world exported about $724 billion more worth of goods and

services to the United States than they imported from the

United States.” Resolve the apparent inconsistency of these

two statements.

10.

KEY QUESTION Diagram a market in which the equilib-

rium dollar price of 1 unit of fictitious currency zee (Z) is $5

(the exchange rate is $5 ⫽ Z1). Then show on your diagram

a decline in the demand for zee.

a. Referring to your diagram, discuss the adjustment op-

tions the United States would have in maintaining the

exchange rate at $5 ⫽ Z1 under a fixed-exchange-rate

system.

b. How would the U.S. balance-of-payments surplus that

is created (by the decline in demand) get resolved under

a system of flexible exchange rates?

11. Compare and contrast the Bretton Woods system of ex-

change rates with that of the gold standard. What caused

the collapse of the gold standard? What caused the demise

of the Bretton Woods system?

12. Describe what is meant by the term “managed float.” Did

the managed-float system precede or follow the adjustable-

peg system? Explain.

13. What have been the major causes of the large U.S. trade

deficits since 1997? What are the major benefits and costs

associated with trade deficits? Explain: “A trade deficit

means that a nation is receiving more goods and services

from abroad than it is sending abroad.” How can that be

called “unfavorable”?

14.

LAST WORD Suppose Winter Sports—a hypothetical

French retailer of snowboards—wants to order 5000 snow-

boards made in the United States. The price per board is

$200, the present exchange rate is 1 euro ⫽ $1, and payment

is due in dollars when the boards are delivered in 3 months.

Use a numerical example to explain why exchange-rate risk

might make the French retailer hesitant to place the order.

How might speculators absorb some of Winter Sports’ risk?

Web-Based Questions

1. THE U.S. BALANCE ON GOODS AND SERVICES—WHAT

ARE THE LATEST FIGURES? The U.S. Census Bureau re-

ports the latest data on U.S. trade in goods and services at

its Web site, www.census.gov/indicator/www/ustrade.

html . In the latest month, did the trade balance in goods

and services improve (that is, yield a smaller deficit or a

larger surplus) or deteriorate? Was the relative trade

strength of the United States compared to the rest of the

world in goods or in services? Which product groups had

the largest increases in exports? Which had the largest in-

creases in imports?

2.

THE YEN-DOLLAR EXCHANGE RATE The Federal Reserve

Board of Governors provides exchange rates for various

currencies for the last decade at www.federalreserve.gov/

releases (Foreign Exchange Rates; Historical bilateral

rates). Has the dollar appreciated, depreciated, or remained

constant relative to the Canadian dollar, the European euro,

the Japanese yen, the Swedish krona, and the Swiss franc

since 2000?

mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 380mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 380 9/15/06 3:32:00 PM9/15/06 3:32:00 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

Note: Terms set in italic type are defined separately in this

glossary.

actual investment The amount that firms invest; equal to

planned investment plus unplanned investment .

actual reserves The funds that a bank has on deposit at the Fed-

eral Reserve Bank of its district (plus its vault cash ).

adjustable pegs The device used in the Bretton Woods system to

alter exchange rates in an orderly way to eliminate persistent pay-

ments deficits and surpluses. Each nation defined its monetary

unit in terms of (pegged it to) gold or the dollar, kept the rate of

exchange for its money stable in the short run, and adjusted its

rate in the long run when faced with international payments

disequilibrium.

aggregate A collection of specific economic units treated as if

they were one. For example, all prices of individual goods and

services are combined into a price level , or all units of output are

aggregated into gross domestic product .

aggregate demand A schedule or curve that shows the total

quantity of goods and services demanded (purchased) at different

price levels .

aggregate demand–aggregate supply (AD-AS) model The

macroeconomic model that uses aggregate demand and aggregate

supply to determine and explain the price level and the real domestic

output .

aggregate expenditures The total amount spent for final goods

and services in an economy.

aggregate expenditures–domestic output approach Deter-

mination of the equilibrium gross domestic product by finding the

real GDP at which aggregate expenditures equal domestic output .

aggregate expenditures schedule

A schedule or curve showing

the total amount spent for final goods and services at different

levels of real GDP .

aggregate supply A schedule or curve showing the total

quantity of goods and services supplied (produced) at different

price levels .

aggregate supply shocks Sudden, large changes in resource

costs that shift an economy’s aggregate supply curve.

allocative efficiency The apportionment of resources among

firms and industries to obtain the production of the products

most wanted by society (consumers); the output of each product

at which its marginal cost and price or marginal benefit are equal.

anticipated inflation Increases in the price level (inflation) that

occur at the expected rate.

appreciation (of the dollar) An increase in the value of the dollar

relative to the currency of another nation, so a dollar buys a larger

amount of the foreign currency and thus of foreign goods.

asset Anything of monetary value owned by a firm or individual.

asset demand for money The amount of money people want to

hold as a store of value; this amount varies inversely with the

interest rate .

average propensity to consume Fraction (or percentage) of

disposable income that households plan to spend for consumer

goods and services; consumption divided by disposable income .

average propensity to save (APS) Fraction (or percentage) of

disposable income that households save; saving divided by disposable

income .

average tax rate Total tax paid divided by total (taxable) income,

as a percentage.

balance of payments (See international balance of payments .)

balance-of- payments deficit The amount by which inpayments

from a nation’s stock of official reserves are required to balance

that nation’s capital and financial account with its current account (in

its balance of payments ).

balance-of- payments surplus The amount by which outpay-

ments to a nation’s stock of official reserves are required to balance

that nation’s capital and financial account with its current account (in

its international balance of payments ).

balance on current account The exports of goods and services

of a nation less its imports of goods and services plus its net

investment income and net transfers in a year.

balance on goods and services The exports of goods and

services of a nation less its imports of goods and services in a year.

balance sheet A statement of the assets, liabilities, and net worth

of a firm or individual at some given time.

bank deposits The deposits that individuals or firms have at

banks (or thrifts) or that banks have at the Federal Reserve Banks .

bankers’ bank A bank that accepts the deposits of and makes

loans to depository institutions; in the United States, a Federal

Reserve Bank .

bank reserves The deposits of commercial banks and thrifts at

Federal Reserve Banks plus bank and thrift vault cash .

barter The exchange of one good or service for another good or

service.

base year

The year with which other years are compared when an

index is constructed; for example, the base year for a price index .

Board of Governors The seven-member group that supervises

and controls the money and banking system of the United States;

the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; the

Federal Reserve Board.

bond A financial device through which a borrower (a firm or

government) is obligated to pay the principal and interest on a

loan at a specific date in the future.

break-even income The level of disposable income at which

households plan to consume (spend) all their income and to save

Glossary

G-1

mcc73082_glo_G1-G18.indd 1mcc73082_glo_G1-G18.indd 1 9/21/06 3:56:06 PM9/21/06 3:56:06 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

G-2 Glossary

none of it; also, in an income transfer program, the level of

earned income at which subsidy payments become zero.

Bretton Woods system The international monetary system

developed after the Second World War in which adjustable pegs

were employed, the International Monetary Fund helped stabilize

foreign exchange rates, and gold and the dollar were used as

international monetary reserves .

budget deficit The amount by which the expenditures of the

Federal government exceed its revenues in any year.

budget surplus The amount by which the revenues of the Fed-

eral government exceed its expenditures in any year.

built-in stabilizer A mechanism that increases government’s

budget deficit (or reduces its surplus) during a recession and in-

creases government’s budget surplus (or reduces its deficit) dur-

ing an expansion without any action by policymakers. The tax

system is one such mechanism.

Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) An agency of the U.S.

Department of Commerce that compiles the national income

and product accounts.

business cycle Recurring increases and decreases in the level of

economic activity over periods of years; consists of peak, reces-

sion, trough, and expansion phases.

business firm (See firm .)

capital Human-made resources (buildings, machinery, and

equipment) used to produce goods and services; goods that do

not directly satisfy human wants; also called capital goods.

capital and financial account The section of a nation’s interna-

tional balance of payments that records (1) debt forgiveness by and

to foreigners and (2) foreign purchases of assets in the United

States and U.S. purchases of assets abroad.

capital and financial account deficit A negative balance on its

capital and financial account in a country’s international balance of

payments .

capital and financial account surplus A positive balance on its

capital and financial account in a country’s international balance of

payments .

capital gain The gain realized when securities or properties are

sold for a price greater than the price paid for them.

capital goods

(See capital .)

capital-intensive commodity A product that requires a rela-

tively large amount of capital to be produced.

capitalism An economic system in which property resources are

privately owned and markets and prices are used to direct and

coordinate economic activities.

capital stock The total available capital in a nation.

cartel A formal agreement among firms (or countries) in an in-

dustry to set the price of a product and establish the outputs of

the individual firms (or countries) or to divide the market for the

product geographically.

causation A relationship in which the occurrence of one or

more events brings about another event.

CEA (See Council of Economic Advisers .)

central bank A bank whose chief function is the control of the

nation’s money supply; in the United States, the Federal Reserve

System.

central economic planning Government determination of the

objectives of the economy and how resources will be directed to

attain those goals.

ceteris paribus assumption (See other-things-equal assumption .)

change in demand A change in the quantity demanded of a good

or service at every price; a shift of the demand curve to the left or

right.

change in quantity demanded A change in the amount of a

product that consumers are willing and able to purchase because

of a change in the product’s price.

change in quantity supplied A change in the amount of a

product that producers offer for sale because of a change in the

product’s price.

change in supply A change in the quantity supplied of a good or

service at every price; a shift of the supply curve to the left or

right.

checkable deposit Any deposit in a commercial bank or thrift in-

stitution against which a check may be written.

checkable-deposit multiplier (See monetary multiplier .)

check clearing The process by which funds are transferred

from the checking accounts of the writers of checks to the check-

ing accounts of the recipients of the checks.

checking account A checkable deposit in a commercial bank or

thrift institution .

circular flow diagram An illustration showing the flow of re-

sources from households to firms and of products from firms to

households. These flows are accompanied by reverse flows of

money from firms to households and from households to

firms.

classical economics The macroeconomic generalizations ac-

cepted by most economists before the 1930s that led to the con-

clusion that a capitalistic economy was self-regulating and

therefore would usually employ its resources fully.

closed economy An economy that neither exports nor imports

goods and services.

coincidence of wants A situation in which the good or service

that one trader desires to obtain is the same as that which an-

other trader desires to give up and an item that the second trader

wishes to acquire is the same as that which the first trader desires

to surrender.

COLA (See cost-of-living adjustment .)

command system A method of organizing an economy in

which property resources are publicly owned and government

uses central economic planning to direct and coordinate economic

activities; command economy; communism.

commercial bank A firm that engages in the business of bank-

ing (accepts deposits, offers checking accounts, and makes

loans).

mcc73082_glo_G1-G18.indd 2mcc73082_glo_G1-G18.indd 2 9/21/06 3:56:07 PM9/21/06 3:56:07 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

Glossary G-3

commercial banking system All commercial banks and thrift in-

stitutions as a group.

communism (See command system .)

comparative advantage A lower relative opportunity cost than

that of another producer or country.

compensation to employees Wa ge s and salaries plus wage and

salary supplements paid by employers to workers.

competition The presence in a market of independent buyers

and sellers competing with one another along with the freedom

of buyers and sellers to enter and leave the market.

complementary goods Products and services that are used to-

gether. When the price of one falls, the demand for the other

increases (and conversely).

conglomerates Firms that produce goods and services in two or

more separate industries.

constant opportunity cost An opportunity cost that remains the

same for each additional unit as a consumer (or society) shifts

purchases (production) from one product to another along a

straight-line budget line ( production possibilities curve ).

consumer goods Products and services that satisfy human

wants directly.

Consumer Price Index (CPI) An index that measures the

prices of a fixed “market basket” of some 300 goods and services

bought by a “typical” consumer.

consumer sovereignty Determination by consumers of the

types and quantities of goods and services that will be produced

with the scarce resources of the economy; consumers’ direction

of production through their dollar votes.

consumer surplus The difference between the maximum price

a consumer is (or consumers are) willing to pay for an additional

unit of a product and its market price; the triangular area below

the demand curve and above the market price.

consumption of fixed capital An estimate of the amount of

capital worn out or used up (consumed) in producing the gross

domestic product; also called depreciation.

consumption schedule A schedule showing the amounts house-

holds

plan to spend for consumer goods at different levels of dispos-

able income .

contractionary fiscal policy A decrease in government purchases

for goods and services, an increase in net taxes , or some combina-

tion of the two, for the purpose of decreasing aggregate demand

and thus controlling inflation.

coordination failure A situation in which people do not reach a

mutually beneficial outcome because they lack some way to

jointly coordinate their actions; a possible cause of macroeco-

nomic instability.

corporate income tax A tax levied on the net income (account-

ing profit) of corporations.

corporation A legal entity (“person”) chartered by a state or the

Federal government that is distinct and separate from the indi-

viduals who own it.

correlation A systematic and dependable association between

two sets of data (two kinds of events); does not necessarily indi-

cate causation.

cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) An automatic increase in

the incomes (wages) of workers when inflation occurs; guaranteed

by a collective bargaining contract between firms and workers.

cost-push inflation Increases in the price level (inflation) re-

sulting from an increase in resource costs (for example, raw-

material prices) and hence in per-unit production costs; inflation

caused by reductions in aggregate supply .

Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) A group of three per-

sons that advises and assists the president of the United States on

economic matters (including the preparation of the annual Eco-

nomic Report of the President ).

creative destruction The hypothesis that the creation of new

products and production methods simultaneously destroys the

market power of existing monopolies.

credit An accounting item that increases the value of an asset

(such as the foreign money owned by the residents of a nation).

credit union An association of persons who have a common tie

(such as being employees of the same firm or members of the

same labor union) that sells shares to (accepts deposits from) its

members and makes loans to them.

crowding-out effect A rise in interest rates and a resulting de-

crease in planned investment caused by the Federal government’s

increased borrowing to finance budget deficits and refinance debt.

currency Coins and paper money.

currency appreciation (See exchange-rate appreciation .)

currency depreciation (See exchange-rate depreciation .)

currency intervention A government’s buying and selling of its

own currency or foreign currencies to alter international ex-

change rates.

current account The section in a nation’s international balance of

payments that records its exports and imports of goods and ser-

vices, its net investment income, and its net transfers .

cyclical asymmetry The idea that monetary policy may be more

successful in slowing expansions and controlling inflation than in

extracting the economy from severe recession.

cyclical deficit A Federal budget deficit that is caused by a reces-

sion and the consequent decline in tax revenues.

cyclical unemployment A type of unemployment caused by in-

sufficient total spending (or by insufficient aggregate demand ).

debit An accounting item that decreases the value of an asset

(such as the foreign money owned by the residents of a nation).

deflating Finding the real gross domestic product by decreasing

the dollar value of the GDP for a year in which prices were

higher than in the base year .

deflation A decline in the economy’s price level .

demand A schedule showing the amounts of a good or service

that buyers (or a buyer) wish to purchase at various prices during

some time period.

mcc73082_glo_G1-G18.indd 3mcc73082_glo_G1-G18.indd 3 9/21/06 3:56:07 PM9/21/06 3:56:07 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES