McConnell С., Campbell R. Macroeconomics: principles, problems, and policies, 17th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PART SIX

International Economics

344

QUICK QUIZ 18.2

1. The production possibilities curves in graphs (a) and (b) imply:

a. increasing domestic opportunity costs.

b. decreasing domestic opportunity costs.

c. constant domestic opportunity costs.

d. first decreasing, then increasing, domestic opportunity costs.

2. Before specialization, the domestic opportunity cost of

producing 1 unit of wheat is:

a. 1 unit of coffee in both the United States and Brazil.

b. 1 unit of coffee in the United States and 2 units of coffee

in Brazil.

c. 2 units of coffee in the United States and 1 unit of coffee

in Brazil.

d. 1 unit of coffee in the United States and

1

_

2

unit of coffee in

Brazil.

3. After specialization and international trade, the world output of

wheat and coffee is:

a. 20 tons of wheat and 20 tons of coffee.

b. 45 tons of wheat and 15 tons of coffee.

c. 30 tons of wheat and 20 tons of coffee.

d. 10 tons of wheat and 30 tons of coffee.

4. After specialization and international trade:

a. the United States can obtain units of coffee at less cost than

it could before trade.

b. Brazil can obtain more than 20 tons of coffee, if it so chooses.

c. the United States no longer has a comparative advantage in

producing wheat.

d. Brazil can benefit by prohibiting coffee imports from the

United States.

key

graph

344

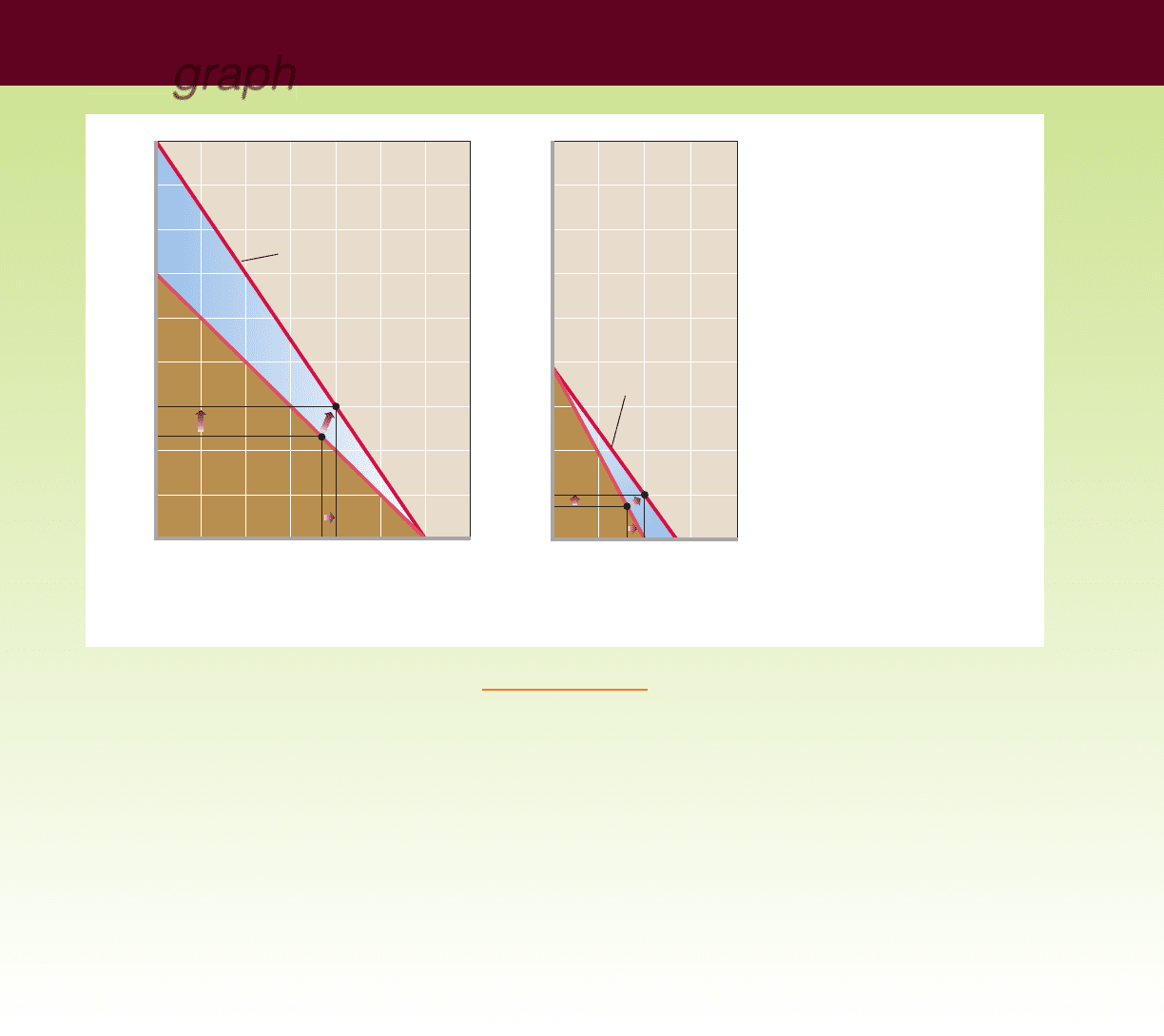

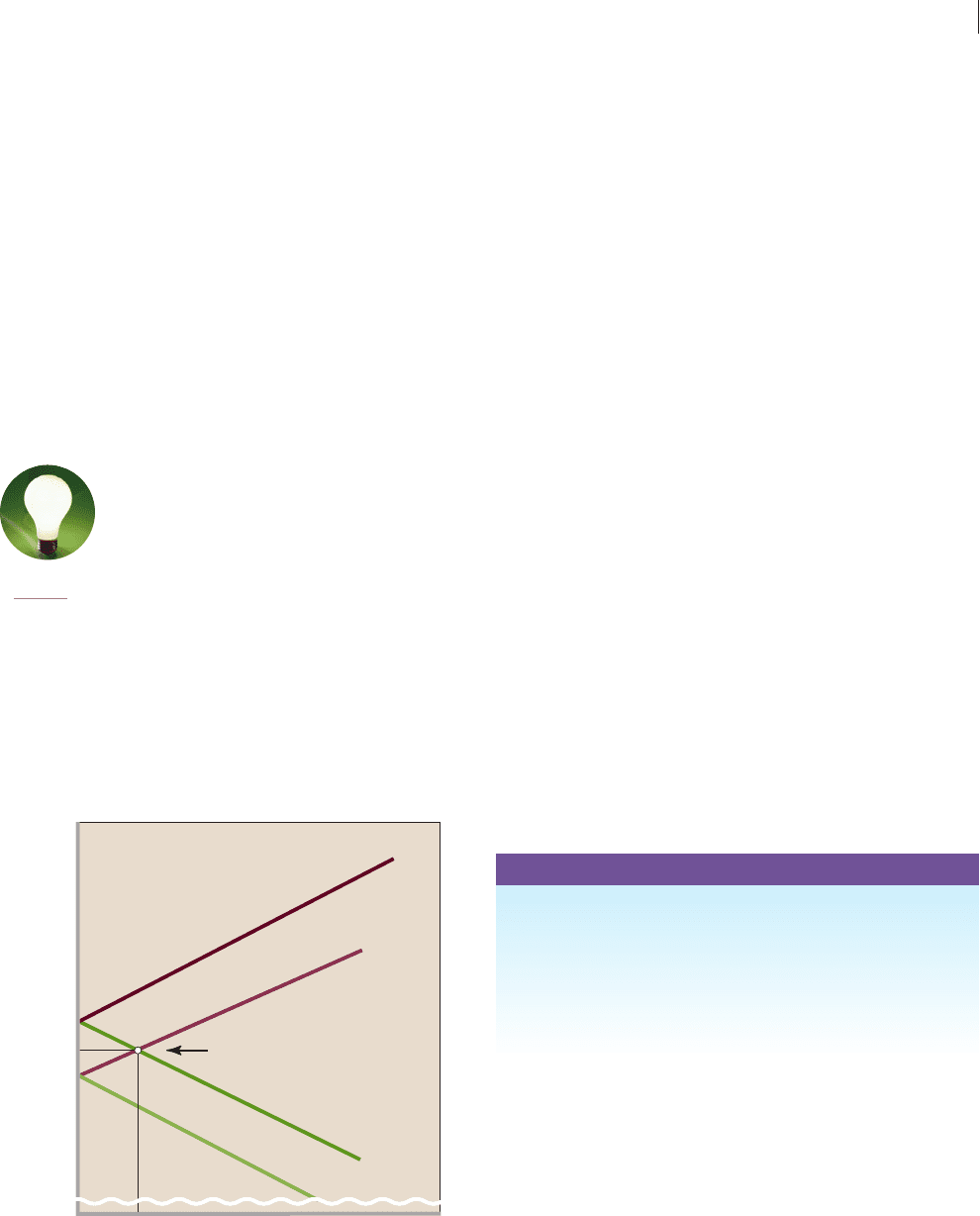

FIGURE 18.2 Trading possibility

lines and the gains from trade. As a

result of specialization and trade, both the

United States and Brazil can have higher levels

of output than the levels attainable on their

domestic production possibilities curves.

(a) The United States can move from point

A on its domestic production possibilities

curve to, say, A ⬘ on its trading possibilities line.

(b) Brazil can move from B to B ⬘ .

Wheat (tons)

(a)

United States

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0 5 10 15 20 25

30

Trading

possibilities line

Cⴕ

Aⴕ

A

W

Coffee (tons)

Wheat (tons)

(b)

Brazil

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

5

10 15 20

Trading

possibilities

line

Bⴕ

B

w

wⴕ

Coffee (tons)

C

c

Answers: 1. c; 2. b; 3. c; 4. a

in one product and trading for the other. The trading pos-

sibilities lines in Figure 18.2 reflect the assumption that

both nations specialize on the basis of comparative advan-

tage: The United States specializes completely in wheat

(at point W in Figure 18.2a ), and Brazil specializes com-

pletely in coffee (at point c in Figure 18.2b ).

Improved Options Now the United States is not

constrained by its domestic production possibilities line,

which requires it to give up 1 ton of wheat for every ton of

coffee it wants as it moves up its domestic production pos-

sibilities line from, say, point W . Instead, the United

States, through trade with Brazil, can get 1

1

_

2

tons of coffee

for every ton of wheat it exports to Brazil, as long as Brazil

has coffee to export. Trading possibilities line WC ⬘ thus

represents the 1 W 1

1

_

2

C trading ratio.

Similarly, Brazil, starting at, say, point c , no longer has

to move down its domestic production possibilities curve,

mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 344mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 344 9/15/06 4:04:01 PM9/15/06 4:04:01 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 18

International Trade

345

giving up 2 tons of coffee for each ton of wheat it wants. It

can now export just 1

1

_

2

tons of coffee for each ton of wheat

it wants by moving down its trading possibilities line cw ⬘.

Specialization and trade create a new exchange ratio

between wheat and coffee, reflected in each nation’s trad-

ing possibilities line. This exchange ratio is superior for

both nations to the unspecialized exchange ratio embod-

ied in their production possibilities curves. By specializing

in wheat and trading for Brazil’s coffee, the United States

can obtain more than 1 ton of coffee for 1 ton of wheat. By

specializing in coffee and trading for U.S. wheat, Brazil

can get 1 ton of wheat for less than 2 tons of coffee. In

both cases, self-sufficiency is undesirable.

Added Output By specializing on the basis of com-

parative advantage and by trading for goods that are pro-

duced in the nation with greater domestic efficiency, the

United States and Brazil can realize combinations of wheat

and coffee beyond their production possibilities curves.

Specialization according to comparative advantage results

in a more efficient allocation of world resources, and larger

outputs of both products are therefore available to both

nations.

Suppose that at the 1 W 1

1

_

2

C terms of trade, the

United States exports 10 tons of wheat to Brazil and in

return Brazil exports 15 tons of coffee to the United States.

How do the new quantities of wheat and coffee available

to the two nations compare with the optimal product

mixes that existed before specialization and trade? Point A

in Figure 18.2a reminds us that the United States chose

18 tons of wheat and 12 tons of coffee originally. But by

producing 30 tons of wheat and no coffee and by trading

10 tons of wheat for 15 tons of coffee, the United States

can obtain 20 tons of wheat and 15 tons of coffee. This

new, superior combination of wheat and coffee is indicated

by point A ⬘ in Figure 18.2a . Compared with the no-trade

amounts of 18 tons of wheat and 12 tons of coffee, the

United States’ gains from trade are 2 tons of wheat and

3 tons of coffee.

Similarly, recall that Brazil’s optimal product mix was

4 tons of coffee and 8 tons of wheat (point B ) before special-

ization and trade. Now, after specializing in coffee and trad-

ing, Brazil can have 5 tons of coffee and 10 tons of wheat. It

accomplishes that by producing 20 tons of coffee and no

wheat and exporting 15 tons of its coffee in exchange for

10 tons of American wheat. This new position is indicated

by point B ⬘ in Figure 18.2b . Brazil’s gains from trade are

1 ton of coffee and 2 tons of wheat.

As a result of specialization and trade, both countries

have more of both products. Table 18.1 , which summa-

rizes the transactions and outcomes, merits careful study.

The fact that points A ⬘ and B ⬘ are economic positions

superior to A and B is enormously important. We know that

a nation can expand its production possibilities boundary by

(1) expanding the quantity and improving

the quality of its resources or (2) realizing

technological progress. We have now estab-

lished that international trade can enable a

nation to circumvent the output constraint

illustrated by its production possibilities

curve. The outcome of international special-

ization and trade is equivalent to having

more and better resources or discovering improved produc-

tion techniques.

Trade with Increasing Costs

To explain the basic principles underlying international

trade, we simplified our analysis in several ways. For ex-

ample, we limited discussion to two products and two

nations. But multiproduct and multinational analysis yields

the same conclusions. We also assumed constant opportu-

nity costs (linear production possibilities curves), which

is a more substantive simplification. Let’s consider the

effect of allowing increasing opportunity costs (concave-

to-the-origin production possibilities curves) to enter the

picture.

Suppose that the United States and Brazil initially are

at positions on their concave production possibilities

curves where their domestic cost ratios are 1 W 1 C and

1 W 2 C , as they were in our constant-cost analysis. As

before, comparative advantage indicates that the United

States should specialize in wheat and Brazil in coffee. But

now, as the United States begins to expand wheat produc-

tion, its cost of wheat will rise; it will have to sacrifice more

than 1 ton of coffee to get 1 additional ton of wheat. Re-

sources are no longer perfectly substitutable between al-

ternative uses, as the constant-cost assumption implied.

Resources less and less suitable to wheat production must

be allocated to the U.S. wheat industry in expanding wheat

output, and that means increasing costs—the sacrifice of

larger and larger amounts of coffee for each additional ton

of wheat.

Similarly, Brazil, starting from its 1 W 2 C cost ratio

position, expands coffee production. But as it does, it will

find that its 1 W 2 C cost ratio begins to rise. Sacrificing

a ton of wheat will free resources that are capable of pro-

ducing only something less than 2 tons of coffee, because

those transferred resources are less suitable to coffee pro-

duction.

As the U.S. cost ratio falls from 1 W 1 C and the

Brazilian ratio rises from 1 W 2 C , a point will be reached

where the cost ratios are equal in the two nations, perhaps

W 18.1

Gains from trade

mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 345mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 345 9/15/06 4:04:01 PM9/15/06 4:04:01 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART SIX

International Economics

346

at 1 W 1

3

_

4

C . At this point the underlying basis for fur-

ther specialization and trade—differing cost ratios—has

disappeared, and further specialization is therefore un-

economical. And, most important, this point of equal

cost ratios may be reached while the United States is still

producing some coffee along with its wheat and Brazil is

producing some wheat along with its coffee. The primary

effect of increasing opportunity costs is less-than-com-

plete specialization. For this reason we often find domes-

tically produced products competing directly against

identical or similar imported products within a particular

economy. (Key Question 4)

The Case for Free Trade

The case for free trade reduces to one compelling argu-

ment: Through free trade based on the principle of com-

parative advantage, the world economy can achieve a more

efficient allocation of resources and a higher level of mate-

rial well-being than it can without free trade.

Since the resource mixes and technological knowledge

of the world’s nations are all somewhat different, each na-

tion can produce particular commodities at different real

costs. Each nation should produce goods for which its do-

mestic opportunity costs are lower than the domestic op-

portunity costs of other nations and exchange those goods

for products for which its domestic opportunity costs are

high relative to those of other nations. If each nation does

this, the world will realize the advantages of geographic

and human specialization. The world and each free-trad-

ing nation can obtain a larger real income from the fixed

supplies of resources available to it. Government trade

barriers lessen or eliminate gains from specialization. If

nations cannot trade freely, they must shift resources from

efficient (low-cost) to inefficient (high-cost) uses in order

to satisfy their diverse wants.

One side benefit of free trade is that it promotes

competition and deters monopoly. The increased com-

petition from foreign firms forces domestic firms to find

and use the lowest-cost production techniques. It also

compels them to be innovative with respect to both

product quality and production methods, thereby con-

tributing to economic growth. And free trade gives con-

sumers a wider range of product choices. The reasons to

favor free trade are the same as the reasons to endorse

competition.

A second side benefit of free trade is that it links na-

tional interests and breaks down national animosities.

Confronted with political disagreements, trading partners

tend to negotiate rather than make war.

Supply and Demand Analysis

of Exports and Imports

Supply and demand analysis reveals how equilibrium prices

and quantities of exports and imports are determined. The

amount of a good or a service a nation will export or import

depends on differences between the equilibrium world price

and the equilibrium domestic price. The interaction of

world supply and demand determines the equilibrium world

price —the price that equates the quantities supplied and

demanded globally. Domestic supply and demand determine

the equilibrium domestic price —the price that would pre-

vail in a closed economy that does not engage in interna-

tional trade. The domestic price equates quantity supplied

and quantity demanded domestically.

In the absence of trade, the domestic prices in a closed

economy may or may not equal the world equilibrium

prices. When economies are opened for international trade,

differences between world and domestic prices encourage

exports or imports. To see how, consider the international

effects of such price differences in a simple two-nation

world, consisting of the United States and Canada, that are

both producing aluminum. We assume there are no trade

barriers, such as tariffs and quotas, and no international

transportation costs.

Supply and Demand in the

United States

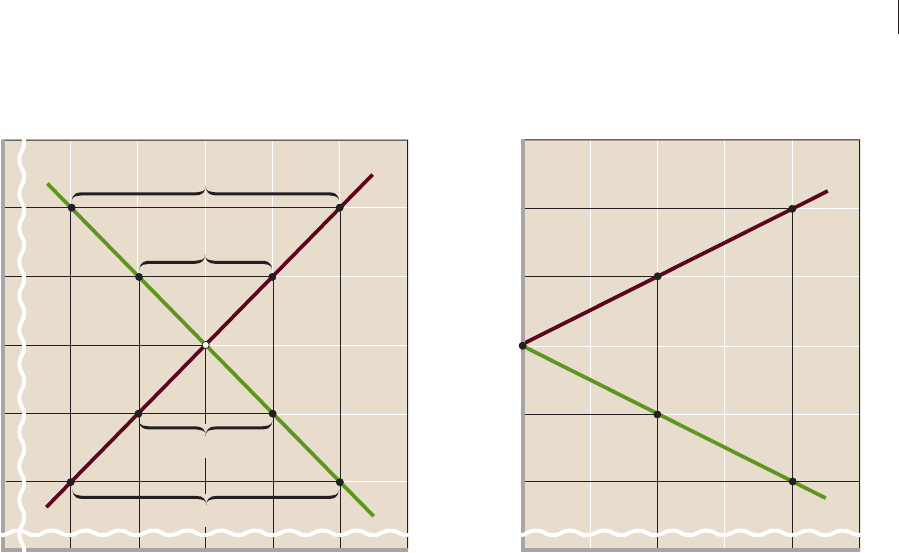

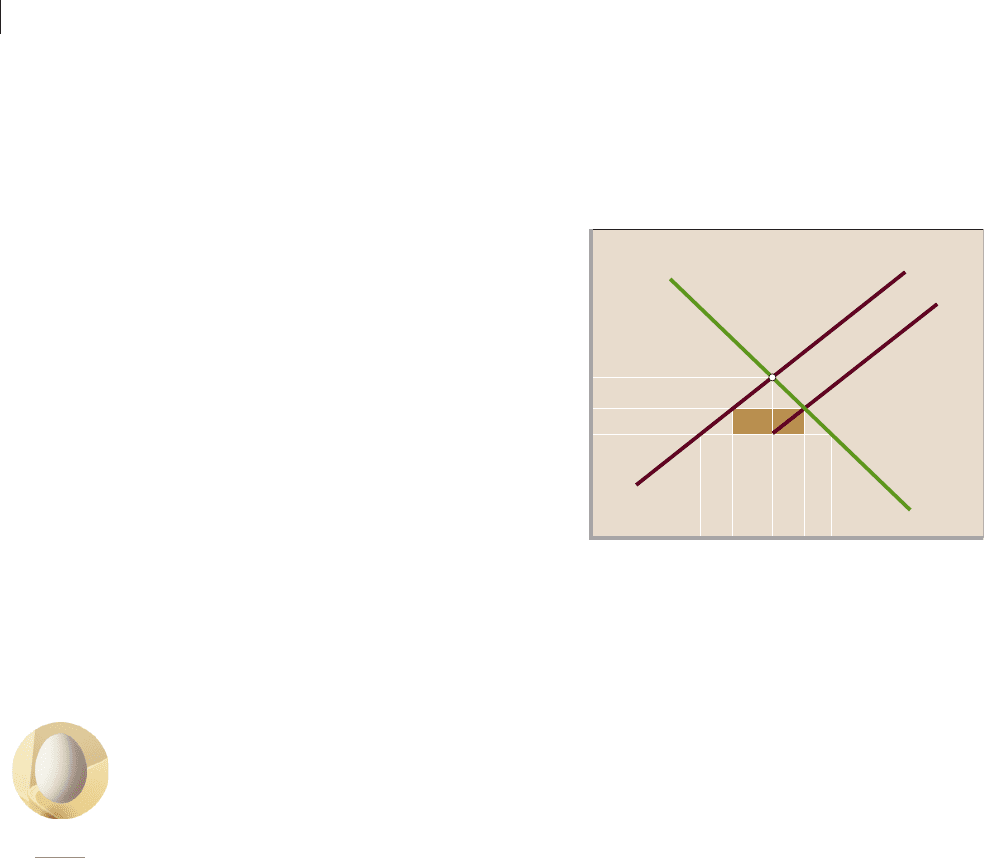

Figure 18.3a shows the domestic supply curve S

d

and the

domestic demand curve D

d

for aluminum in the United

States, which for now is a closed economy. The intersec-

tion of S

d

and D

d

determines the equilibrium domestic

price of $1 per pound and the equilibrium domestic

quantity of 100 million pounds. Domestic suppliers

produce 100 million pounds and sell them all at $1 a

pound. So there are no domestic surpluses or shortages

of aluminum.

QUICK REVIEW 18.1

• International trade enables nations to specialize, increase

productivity, and increase output available for consumption.

• Comparative advantage means total world output will be

greatest when each good is produced by the nation that has

the lowest domestic opportunity cost.

• Specialization is less than complete among nations because

opportunity costs normally rise as any given nation produces

more of a particular good.

mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 346mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 346 9/15/06 4:04:02 PM9/15/06 4:04:02 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 18

International Trade

347

But what if the U.S. economy were opened to trade

and the world price of aluminum were above or below this

$1 domestic price?

U.S. Export Supply If the aluminum price in the

rest of the world (that is, Canada) exceeds $1, U.S. firms

will produce more than 100 million pounds and will export

the excess domestic output. First, consider a world price of

$1.25. We see from the supply curve S

d

that U.S. aluminum

firms will produce 125 million pounds of aluminum at that

price. The demand curve D

d

tells us that the United States

will purchase only 75 million pounds at $1.25. The out-

come is a domestic surplus of 50 million pounds of alumi-

num. U.S. producers will export those 50 million pounds at

the $1.25 world price.

What if the world price were $1.50? The supply curve

shows that U.S. firms will produce 150 million pounds of

aluminum, while the demand curve tells us that U.S. con-

sumers will buy only 50 million pounds. So U.S. producers

will export the domestic surplus of 100 million pounds.

Toward the top of Figure 18.3b we plot the domestic

surpluses—the U.S. exports—that occur at world prices

above the $1 domestic equilibrium price. When the world

and domestic prices are equal (⫽ $1), the quantity of ex-

ports supplied is zero (point a ). There is no surplus of do-

mestic output to export. But when the world price is $1.25,

U.S. firms export 50 million pounds of surplus aluminum

(point b ). At a $1.50 world price, the domestic surplus of

100 million pounds is exported (point c ).

The U.S. export supply curve, found by connecting

points a , b , and c , shows the amount of aluminum U.S.

producers will export at each world price above $1. This

curve slopes upward, indicating a direct or positive relation-

ship between the world price and the amount of U.S.

exports. As world prices increase relative to domestic

prices, U.S. exports rise.

U.S. Import Demand If the world price is below

the domestic $1 price, the United States will import alu-

minum. Consider a $.75 world price. The supply curve in

Figure 18.3a reveals that at that price U.S. firms produce

only 75 million pounds of aluminum. But the demand

curve shows that the United States wants to buy 125 mil-

lion pounds at that price. The result is a domestic shortage

of 50 million pounds. To satisfy that shortage, the United

States will import 50 million pounds of aluminum.

0

Quantity of aluminum

(millions of pounds)

(b)

U.S. export supply

and import demand

50 100

0

Price (per pound; U.S. dollars)

.50

Quantity of aluminum

(millions of pounds)

(a)

U.S. domestic

aluminum market

.75

1.00

1.25

$1.50

50 75 100 125 150

U.S.

export

supply

U.S.

import

demand

y

b

c

a

x

Shortage = 50

Shortage = 100

Surplus = 50

Surplus = 100

S

d

D

d

.50

.75

1.00

1.25

$1.50

Price (per pound; U.S. dollars)

FIGURE 18.3 U.S. export supply and import demand. (a) Domestic supply S

d

and demand D

d

set the domestic equilibrium price of aluminum

at $1 per pound. At world prices above $1 there are domestic surpluses of aluminum. At prices below $1 there are domestic shortages. (b) Surpluses are exported

(top curve), and shortages are met by importing aluminum (lower curve). The export supply curve shows the direct relationship between world prices and U.S.

exports; the import demand curve portrays the inverse relationship between world prices and U.S. imports.

mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 347mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 347 9/15/06 4:04:02 PM9/15/06 4:04:02 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART SIX

International Economics

348

At an even lower world price, $.50, U.S. producers

will supply only 50 million pounds. Because U.S. consum-

ers want to buy 150 million pounds at that price, there is a

domestic shortage of 100 million pounds. Imports will

flow to the United States to make up the difference. That

is, at a $.50 world price U.S. firms will supply 50 million

pounds and 100 million pounds will be imported.

In Figure 18.3b we plot the U.S. import demand curve

from these data. This downsloping curve shows the amounts

of aluminum that will be imported at world prices below the

$1 U.S. domestic price. The relationship between world

prices and imported amounts is inverse or negative. At a

world price of $1, domestic output will satisfy U.S. demand;

imports will be zero (point a ). But at $.75 the United States

will import 50 million pounds of aluminum (point x ); at

$.50, the United States will import 100 million pounds

(point y ). Connecting points a, x, and y yields the downsloping

U.S. import demand curve. It reveals that as world prices fall

relative to U.S. domestic prices, U.S. imports increase.

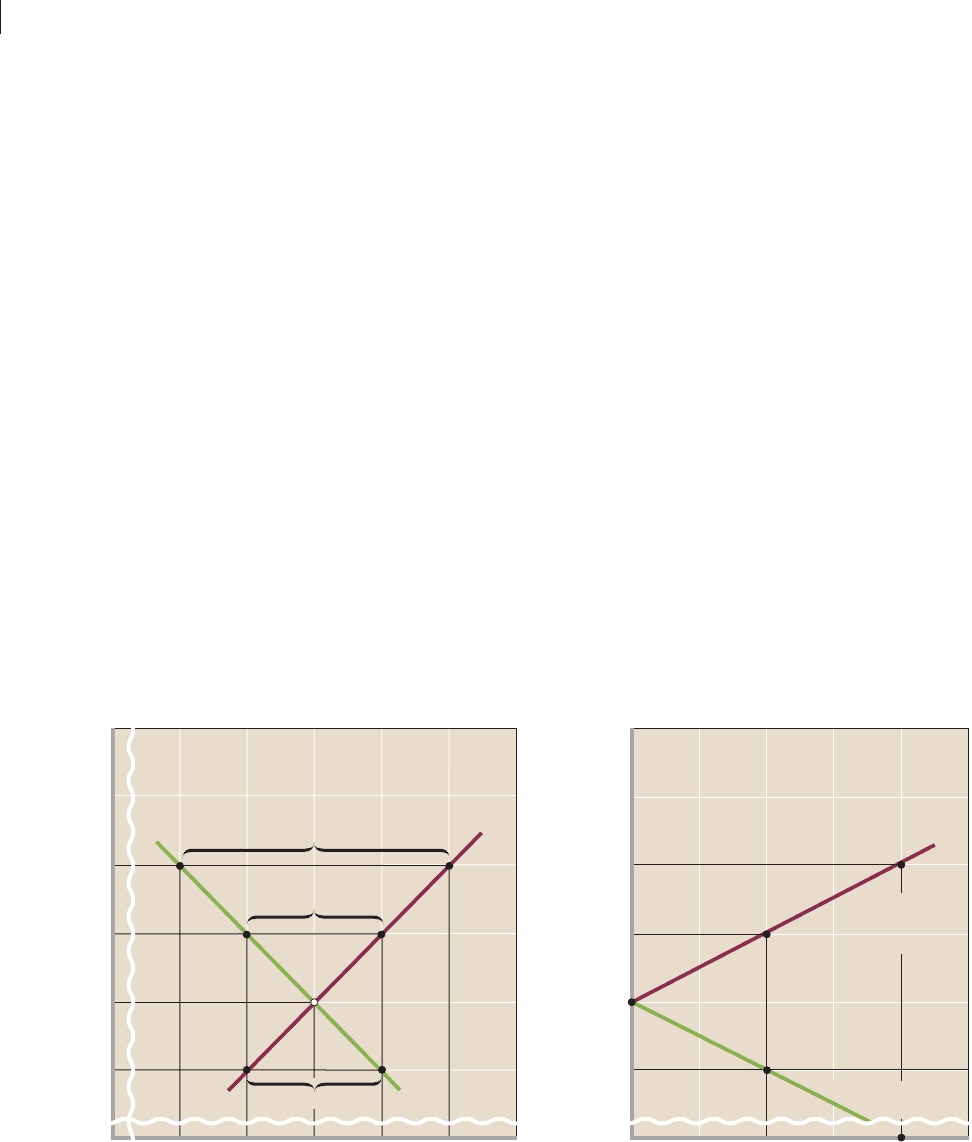

Supply and Demand in Canada

We repeat our analysis in Figure 18.4 , this time from the

viewpoint of Canada. (We have converted Canadian dollar

prices to U.S. dollar prices via the exchange rate.) Note that

the domestic supply curve S

d

and the domestic demand

curve D

d

for aluminum in Canada yield a domestic price of

$.75, which is $.25 lower than the $1 U.S. domestic price.

The analysis proceeds exactly as above except that the

domestic price is now the Canadian price. If the world price

is $.75, Canadians will neither export nor import aluminum

(giving us point q in Figure 18.4b ). At world prices above

$.75, Canadian firms will produce more aluminum than

Canadian consumers will buy. Canadian firms will export

the surplus. At a $1 world price, Figure 18.4b tells us that

Canada will have and export a domestic surplus of 50 million

pounds (yielding point r ). At $1.25, it will have and will

export a domestic surplus of 100 million pounds (point s ).

Connecting these points yields the upsloping Canadian ex-

port supply curve, which reflects the domestic surpluses

(and hence the exports) that occur when the world price

exceeds the $.75 Canadian domestic price.

At world prices below $.75, domestic shortages occur

in Canada. At a $.50 world price, Figure 18.4a shows that

Canadian consumers want to buy 125 million pounds of

aluminum but Canadian firms will produce only 75 million

pounds. The shortage will bring 50 million pounds of

FIGURE 18.4 Canadian export supply and import demand. (a) At world prices above the $.75 domestic price, production in Canada

exceeds domestic consumption. At world prices below $.75, domestic shortages occur. (b) Surpluses result in exports, and shortages result in imports. The Canadian

export supply curve and import demand curve depict the relationships between world prices and exports or imports.

0

Price (per pound; U.S. dollars)

.50

.75

1.00

1.25

$1.50

50 75 100 125 150

Price (per pound; U.S. dollars)

0

.50

.75

1.00

1.25

$1.50

50 100

Canadian

export

supply

r

s

q

t

S

d

D

d

Canadian import

demand

Surplus = 50

Surplus = 100

Shortage = 50

Quantity of aluminum

(millions of pounds)

(b)

Canada’s export supply

and import demand

Quantity of aluminum

(millions of pounds)

(a)

Canada’s domestic

aluminum market

mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 348mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 348 9/15/06 4:04:02 PM9/15/06 4:04:02 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 18

International Trade

349

imports to Canada (point t in Figure 18.4b ). The Canadian

import demand curve in that figure shows the Canadian im-

ports that will occur at all world aluminum prices below the

$.75 Canadian domestic price.

Equilibrium World Price,

Exports, and Imports

We now have the tools for determining the equilibrium

world price of aluminum and the equilibrium world levels

of exports and imports when the world is opened to trade.

Figure 18.5 combines the U.S. export supply curve and im-

port demand curve in Figure 18.3b and the Canadian ex-

port supply curve and import demand curve in Figure 18.4b .

The two U.S. curves proceed rightward from the $1 U.S.

domestic price; the two Canadian curves proceed rightward

from the $.75 Canadian domestic price.

International equilibrium occurs in

this two-nation model where one nation’s

import demand curve intersects another

nation’s export supply curve. In this case

the U.S. import demand curve intersects

Canada’s export supply curve at e . There,

the world price of aluminum is $.88. The

Canadian export supply curve indicates

that Canada will export 25 million pounds

of aluminum at this price. Also at this price the United

States will import 25 million pounds from Canada, indi-

cated by the U.S. import demand curve. The $.88 world

price equates the quantity of imports demanded and the

quantity of exports supplied (25 million pounds). Thus

there will be world trade of 25 million pounds of alumi-

num at $.88 per pound.

Note that after trade, the single $.88 world price will

prevail in both Canada and the United States. Only one

price for a standardized commodity can persist in a highly

competitive world market. With trade, all consumers can

buy a pound of aluminum for $.88, and all producers can

sell it for that price. This world price means that Canadians

will pay more for aluminum with trade ($.88) than without

it ($.75). The increased Canadian output caused by trade

raises Canadian per-unit production costs and therefore

raises the price of aluminum in Canada. The United States,

however, pays less for aluminum with trade ($.88) than

without it ($1). The U.S. gain comes from Canada’s com-

parative cost advantage in producing aluminum.

Why would Canada willingly send 25 million pounds

of its aluminum output to the United States for U.S. con-

sumption? After all, producing this output uses up scarce

Canadian resources and drives up the price of aluminum

for Canadians. Canadians are willing to export aluminum

to the United States because Canadians gain the means—

the U.S. dollars—to import other goods, say, computer

software, from the United States. Canadian exports enable

Canadians to acquire imports that have greater value to

Canadians than the exported aluminum. Canadian exports

to the United States finance Canadian imports from the

United States. (Key Question 6)

FIGURE 18.5 Equilibrium world price and quantity of

exports and imports. In a two-nation world, the equilibrium world

price (⫽ $.88) is determined by the intersection of one nation’s export supply

curve and the other nation’s import demand curve. This intersection also

decides the equilibrium volume of exports and imports. Here, Canada exports

25 million pounds of aluminum to the United States.

Price (per pound; U.S. dollars)

0

Quantity of aluminum (millions of pounds)

.75

.88

$1.00

25

Canadian

export

supply

U.S. import

demand

U.S. export

supply

Canadian import

demand

e

Equilibrium

QUICK REVIEW 18.2

• A nation will export a particular product if the world price

exceeds the domestic price; it will import the product if the

world price is less than the domestic price.

• In a two-country world model, equilibrium world prices and

equilibrium quantities of exports and imports occur where

one nation’s export supply curve intersects the other nation’s

import demand curve.

Trade Barriers

No matter how compelling the case for free trade, barriers

to free trade do exist. Let’s expand Chapter 5’s discussion

of trade barriers.

Excise taxes on imported goods are called tariffs; they

may be imposed to obtain revenue or to protect domestic

W 18.2

Equilibrium world

price, exports, and

imports

mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 349mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 349 9/15/06 4:04:03 PM9/15/06 4:04:03 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART SIX

International Economics

350

firms. A revenue tariff is usually applied to a product that

is not being produced domestically, for example, tin,

coffee, or bananas in the case of the United States. Rates

on revenue tariffs are modest; their purpose is to provide

the Federal government with revenue. A protective tariff

is designed to shield domestic producers from foreign

competition. Although protective tariffs are usually not

high enough to stop the importation of foreign goods,

they put foreign producers at a competitive disadvantage

in selling in domestic markets.

An import quota specifies the maximum amount of a

commodity that may be imported in any period. Import

quotas can more effectively retard international commerce

than tariffs. A product might be imported in large quanti-

ties despite high tariffs; low import quotas completely

prohibit imports once quotas have been filled.

A nontariff barrier (NTB) is a licensing requirement

that specifies unreasonable standards pertaining to prod-

uct quality and safety, or unnecessary bureaucratic red tape

that is used to restrict imports. Japan and the European

countries frequently require that their domestic importers

of foreign goods obtain licenses. By restricting the issu-

ance of licenses, imports can be restricted. The United

Kingdom uses this barrier to bar the importation of coal.

A voluntary export restriction (VER) is a trade bar-

rier by which foreign firms “voluntarily” limit the amount

of their exports to a particular country. VERs, which have

the effect of import quotas, are agreed to by

exporters in the hope of avoiding more

stringent trade barriers. In the late 1990s,

for example, Canadian producers of soft-

wood lumber (fir, spruce, cedar, pine) agreed

to a VER on exports to the United States

under the threat of a permanently higher

U.S. tariff. Later in this chapter we will con-

sider the arguments and appeals that are made to justify

protection.

Economic Impact of Tariffs

Once again we turn to supply and demand analysis—now to

examine the economic effects of protective tariffs. Curves

D

d

and S

d

in Figure 18.6 show domestic demand and supply

for a product in which a nation, say, the United States, has a

comparative disadvantage—for example, digital versatile

disk (DVD) players. (Disregard curve S

d

⫹ Q for now.)

Without world trade, the domestic price and output would

be P

d

and q , respectively.

Assume now that the domestic economy is opened to

world trade and that the Japanese, who have a comparative

advantage in DVD players, begin to sell their players in

the United States. We assume that with free trade the

domestic price cannot differ from the world price, which

here is P

w

. At P

w

domestic consumption is d and domestic

production is a . The horizontal distance between the do-

mestic supply and demand curves at P

w

represents imports

of ad . Thus far, our analysis is similar to the analysis of

world prices in Figure 18.3 .

Direct Effects Suppose now that the United States

imposes a tariff on each imported DVD player. The tariff,

which raises the price of imported players from P

w

to P

t

,

has four effects:

• Decline in consumption Consumption of DVD

players in the United States declines from d to c as the

higher price moves buyers up and to the left along

their demand curve. The tariff prompts consumers to

buy fewer players, and reallocate a portion of their

expenditures to less desired substitute products. U.S.

consumers are clearly injured by the tariff, since they

pay P

w

P

t

more for each of the c units they buy at

price P

t

.

• Increased domestic production U.S. producers—who

are not subject to the tariff—receive the higher price

P

t

per unit. Because this new price is higher than the

pretariff world price P

w

, the domestic DVD-player

industry moves up and to the right along its supply

curve S

d

, increasing domestic output from a to b .

Domestic producers thus enjoy both a higher price

O 18.2

Mercantilism

FIGURE 18.6 The economic effects of a protective

tariff or an import quota. A tariff that increases the price of a good

from P

w

to P

t

will reduce domestic consumption from d to c . Domestic

producers will be able to sell more output ( b rather than a ) at a higher price

( P

t

rather than P

w

). Foreign exporters are injured because they sell less

output ( bc rather than ad ). The brown area indicates the amount of tariff paid

by domestic consumers. An import quota of bc units has the same effect as

the tariff, with one exception: The amount represented by the brown area

will go to foreign producers rather than to the domestic government.

P

d

P

t

P

w

Price

0

ab

q

cd

Quantity

S

d

S

d

+ Q

D

d

mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 350mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 350 9/15/06 4:04:03 PM9/15/06 4:04:03 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 18

International Trade

351

and expanded sales; this explains why domestic

producers lobby for protective tariffs. But from a

social point of view, the greater domestic production

from a to b means that the tariff permits domestic

producers of players to bid resources away from

other, more efficient, U.S. industries.

• Decline in imports Japanese producers are hurt.

Although the sales price of each player is higher by

P

w

P

t

, that amount accrues to the U.S. government,

not to Japanese producers. The after-tariff world

price, or the per-unit revenue to Japanese producers,

remains at P

w

, but the volume of U.S. imports

(Japanese exports) falls from ad to bc .

• Tariff revenue The brown rectangle represents the

amount of revenue the tariff yields. Total revenue

from the tariff is determined by multiplying the tariff,

P

w

P

t

per unit, by the number of players imported, bc .

This tariff revenue is a transfer of income from

consumers to government and does not represent any

net change in the nation’s economic well-being. The

result is that government gains this portion of what

consumers lose by paying more for DVD players.

Indirect Effect Tariffs have a subtle effect beyond

what our supply and demand diagram can show. Because

Japan sells fewer DVD players in the United States, it

earns fewer dollars and so must buy fewer U.S. exports.

U.S. export industries must then cut production and re-

lease resources. These are highly efficient industries, as we

know from their comparative advantage and their ability

to sell goods in world markets.

Tariffs directly promote the expansion of inefficient

industries that do not have a comparative advantage; they

also indirectly cause the contraction of relatively efficient

industries that do have a comparative advantage. Put

bluntly, tariffs cause resources to be shifted in the wrong

direction—and that is not surprising. We know that spe-

cialization and world trade lead to more efficient use of

world resources and greater world output. But protective

tariffs reduce world trade. Therefore, tariffs also reduce

efficiency and the world’s real output.

Economic Impact of Quotas

We noted earlier that an import quota is a legal limit placed

on the amount of some product that can be imported in a

given year. Quotas have the same economic impact as a tar-

iff, with one big difference: While tariffs generate revenue

for the domestic government, a quota transfers that revenue

to foreign producers.

Suppose in Figure 18.6 that, instead of imposing a

tariff, the United States prohibits any imports of Japanese

DVD players in excess of bc units. In other words, an im-

port quota of bc players is imposed on Japan. We deliber-

ately chose the size of this quota to be the same amount as

imports would be under a P

w

P

t

tariff so that we can com-

pare “equivalent” situations. As a consequence of the

quota, the supply of players is S

d

⫹ Q in the United States.

This supply consists of the domestic supply plus the fixed

amount bc (⫽ Q ) that importers will provide at each do-

mestic price. The supply curve S

d

⫹ Q does not extend

below price P

w

, because Japanese producers would not ex-

port players to the United States at any price below P

w

;

instead, they would sell them to other countries at the

world market price of P

w

.

Most of the economic results are the same as those

with a tariff. Prices of DVD players are higher ( P

t

instead

of P

w

) because imports have been reduced from ad to bc .

Domestic consumption of DVD players is down from d

to c . U.S. producers enjoy both a higher price ( P

t

rather

than P

w

) and increased sales ( b rather than a ).

The difference is that the price increase of P

w

P

t

paid

by U.S. consumers on imports of bc —the brown area—no

longer goes to the U.S. Treasury as tariff (tax) revenue but

flows to the Japanese firms that have acquired the rights to

sell DVD players in the United States. For consumers in

the United States, a tariff produces a better economic out-

come than a quota, other things being the same. A tariff

generates government revenue that can be used to cut

other taxes or to finance public goods and services that

benefit the United States. In contrast, the higher price

created by quotas results in additional revenue for foreign

producers. (Key Question 7)

Net Costs of Tariffs and Quotas

Figure 18.6 shows that tariffs and quotas impose costs on

domestic consumers but provide gains to domestic pro-

ducers and, in the case of tariffs, revenue to the Federal

government. The consumer costs of trade restrictions are

calculated by determining the effect the restrictions have

on consumer prices. Protection raises the price of a prod-

uct in three ways: (1) The price of the imported product

goes up; (2) the higher price of imports causes some con-

sumers to shift their purchases to higher-priced domesti-

cally produced goods; and (3) the prices of domestically

produced goods rise because import competition has de-

clined.

Study after study finds that the costs to consumers sub-

stantially exceed the gains to producers and government. A

sizable net cost or efficiency loss to society arises from trade

protection. Furthermore, industries employ large amounts

of economic resources to influence Congress to pass and

retain protectionist laws. Because these rent-seeking efforts

mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 351mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 351 9/15/06 4:04:03 PM9/15/06 4:04:03 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART SIX

International Economics

352

divert resources away from more socially desirable pur-

poses, trade restrictions impose that cost on society.

Conclusion: The gains that U.S. trade barriers create

for protected industries and their workers come at the ex-

pense of much greater losses for the entire economy. The

result is economic inefficiency.

The Case for Protection:

A Critical Review

Despite the logic of specialization and trade, there are still

protectionists in some union halls, corporate boardrooms,

and the halls of Congress. What arguments do protection-

ists make to justify trade barriers? How valid are those

arguments?

Military Self-Sufficiency

Argument

The argument here is not economic but political-military:

Protective tariffs are needed to preserve or strengthen in-

dustries that produce the materials essential for national

defense. In an uncertain world, the political-military

objectives (self-sufficiency) sometimes must take prece-

dence over economic goals (efficiency in the use of world

resources).

Unfortunately, it is difficult to measure and compare the

benefit of increased national security against the cost of eco-

nomic inefficiency when protective tariffs are imposed. The

economist can only point out that when a nation levies tariffs

to increase military self-sufficiency it incurs economic costs.

All people in the United States would agree that rely-

ing on hostile nations for necessary military equipment is

not a good idea, yet the self-sufficiency argument is open to

serious abuse. Nearly every industry can claim that it makes

direct or indirect contributions to national security and

hence deserves protection from imports.

Are there not better ways than tariffs to provide needed

strength in strategic industries? When it is achieved through

tariffs, this self-sufficiency increases the domestic prices of

the products of the protected industry. Thus only those

consumers who buy the industry’s products shoulder the

cost of greater military security. A direct subsidy to strategic

industries, financed out of general tax revenues, would dis-

tribute those costs more equitably.

Diversification-for-Stability

Argument

Highly specialized economies such as Saudi Arabia (based

on oil) and Cuba (based on sugar) are dependent on inter-

national markets for their income. In these economies,

wars, international political developments, recessions

abroad, and random fluctuations in world supply and demand

for one or two particular goods can cause deep declines in

export revenues and therefore in domestic income. Tariff

and quota protection are allegedly needed in such nations

to enable greater industrial diversification. That way, these

economies will not be so dependent on exporting one or

two products to obtain the other goods they need. Such

goods will be available domestically, thereby providing

greater domestic stability.

CONSIDER THIS . . .

Shooting

Yourself in

the Foot

In the lore of the

Wild West, a

gunslinger on oc-

casion would ac-

cidentally pull

the trigger on his

pistol while re-

trieving it from its holster, shooting himself in the foot. Since

then, the phrase “shooting yourself in the foot” implies doing

damage to yourself rather than the intended party.

That is precisely how economist Paul Krugman sees a trade

war:

A trade war in which countries restrict each other’s exports

in pursuit of some illusory advantage is not much like a real

war. On the one hand, nobody gets killed. On the other, unlike

real wars, it is almost impossible for anyone to win, since the

main losers when a country imposes barriers to trade are not

foreign exporters but domestic residents. In effect, a trade

war is a conflict in which each country uses most of its am-

munition to shoot itself in the foot.*

The same analysis is applicable to trade boycotts between

major trading partners. Such a boycott was encouraged by

some American commentators against French imports because

of the opposition of France to the U.S.- and British-led war in

Iraq. But the decline of exports to the United States would

leave the French with fewer U.S. dollars to buy American ex-

ports. So the unintended effect would be a decline in U.S. ex-

ports to France and reduced employment in U.S. export

industries. Moreover, such a trade boycott, if effective, might

lead French consumers to retaliate against American imports.

As with a “tariff war,” a “boycott war” typically harms oneself

as much as the other party.

*Paul Krugman, Peddling Prosperity (New York: Norton, 1994), p. 287.

mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 352mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 352 9/15/06 4:04:04 PM9/15/06 4:04:04 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 18

International Trade

353

There is some truth in this diversification-for-stability

argument. But the argument has little or no relevance to

the United States and other advanced economies. Also,

the economic costs of diversification may be great; for ex-

ample, one-crop economies may be highly inefficient at

manufacturing.

Infant Industry Argument

The infant industry argument contends that protective

tariffs are needed to allow new domestic industries to

establish themselves. Temporarily shielding young

domestic firms from the severe competition of more

mature and more efficient foreign firms will give in-

fant industries a chance to develop and become efficient

producers.

This argument for protection rests on an alleged excep-

tion to the case for free trade. The exception is that young

industries have not had, and if they face mature foreign com-

petition will never have, the chance to make the long-run

adjustments needed for larger scale and greater efficiency in

production. In this view, tariff protection for such infant

industries will correct a misallocation of world resources

perpetuated by historically different levels of economic

development between domestic and foreign industries.

Counterarguments There are some logical prob-

lems with the infant industry argument. In the developing

nations it is difficult to determine which industries are the

infants that are capable of achieving economic maturity and

therefore deserving protection. Also, protective tariffs may

persist even after industrial maturity has been realized.

Most economists feel that if infant industries are to be

subsidized, there are better means than tariffs for doing

so. Direct subsidies, for example, have the advantage of

making explicit which industries are being aided and to

what degree.

Strategic Trade Policy In recent years the infant

industry argument has taken a modified form in advanced

economies. Now proponents contend that government

should use trade barriers to reduce the risk of investing in

product development by domestic firms, particularly

where advanced technology is involved. Firms protected

from foreign competition can grow more rapidly and

achieve greater economies of scale than unprotected for-

eign competitors. The protected firms can eventually

dominate world markets because of their lower costs. Sup-

posedly, dominance of world markets will enable the do-

mestic firms to return high profits to the home nation.

These profits will exceed the domestic sacrifices caused by

trade barriers. Also, advances in high-technology indus-

tries are deemed beneficial, because the advances achieved

in one domestic industry often can be transferred to other

domestic industries.

Japan and South Korea, in particular, have been ac-

cused of using this form of strategic trade policy. The

problem with this strategy and therefore with this argu-

ment for tariffs is that the nations put at a disadvantage by

strategic trade policies tend to retaliate with tariffs of their

own. The outcome may be higher tariffs worldwide, re-

duction of world trade, and the loss of potential gains from

technological advances.

Protection-against-Dumping

Argument

The protection-against dumping argument contends that

tariffs are needed to protect domestic firms from “dump-

ing” by foreign producers. Dumping is the selling of ex-

cess goods in a foreign market at a price below cost.

Economists cite two plausible reasons for this behavior.

First, firms may use dumping abroad to drive out domestic

competitors there, thus obtaining monopoly power and

monopoly prices and profits for the importing firm. The

long-term economic profits resulting from this strategy

may more than offset the earlier losses that accompany the

below-cost sales.

Second, dumping may be a form of price discrimina-

tion, which is charging different prices to different cus-

tomers even though costs are the same. The foreign seller

may find it can maximize its profit by charging a high price

in its monopolized domestic market while unloading its

surplus output at a lower price in the United States. The

surplus output may be needed so that the firm can obtain

the overall per-unit cost saving associated with large-scale

production. The higher profit in the home market more

than makes up for the losses incurred on sales abroad.

Because dumping is an “unfair trade practice,” most

nations prohibit it. For example, where dumping is shown

to injure U.S. firms, the Federal government imposes tar-

iffs called antidumping duties on the specific goods. But

relatively few documented cases of dumping occur each

year, and specific instances of unfair trade do not justify

widespread, permanent tariffs. Moreover, antidumping

duties can be abused. Often, what appears to be dumping

is simply comparative advantage at work.

Increased Domestic Employment

Argument

Arguing for a tariff to “save U.S. jobs” becomes fashion-

able when the economy encounters a recession or experi-

ences slow job growth during a recovery (as in the early

mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 353mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 353 9/15/06 4:04:04 PM9/15/06 4:04:04 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES