McConnell С., Campbell R. Macroeconomics: principles, problems, and policies, 17th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PART SIX

International Economics

354

2000s in the United States). In an economy that engages

in international trade, exports involve spending on do-

mestic output and imports reflect spending to obtain part

of another nation’s output. So, in this argument, reducing

imports will divert spending on another nation’s output to

spending on domestic output. Thus domestic output and

employment will rise. But this argument has several

shortcomings.

While imports may eliminate some U.S. jobs, they

create others. Imports may have eliminated the jobs of

some U.S. steel and textile workers in recent years, but

other workers have gained jobs unloading ships, flying

imported aircraft, and selling imported electronic equip-

ment. Import restrictions alter the composition of em-

ployment, but they may have little or no effect on the

volume of employment.

The fallacy of composition —the false idea that what is

true for the part is necessarily true for the whole—is also

present in this rationale for tariffs. All nations cannot

simultaneously succeed in restricting imports while main-

taining their exports; what is true for one nation is not

true for all nations. The exports of one nation must be the

imports of another nation. To the extent that one country

is able to expand its economy through an excess of exports

over imports, the resulting excess of imports over exports

worsens another economy’s unemployment problem. It

is no wonder that tariffs and import quotas meant to

achieve domestic full employment are called “beggar my

neighbor” policies: They achieve short-run domestic goals

by making trading partners poorer.

Moreover, nations adversely affected by tariffs and

quotas are likely to retaliate, causing a “trade-barrier war”

that will choke off trade and make all nations worse off.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 is a classic exam-

ple. Although that act was meant to reduce imports and

stimulate U.S. production, the high tariffs it authorized

prompted adversely affected nations to retaliate with tar-

iffs equally high. International trade fell, lowering the out-

put and income of all nations. Economic historians

generally agree that the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was a

contributing cause of the Great Depression.

Finally, forcing an excess of exports over imports can-

not succeed in raising domestic employment over the long

run. It is through U.S. imports that foreign nations earn

dollars for buying U.S. exports. In the long run a nation

must import in order to export. The long-run impact of

tariffs is not an increase in domestic employment but, at

best, a reallocation of workers away from export industries

and to protected domestic industries. This shift implies a

less efficient allocation of resources.

Cheap Foreign Labor Argument

The cheap foreign labor argument says that domestic firms

and workers must be shielded from the ruinous competition

of countries where wages are low. If protection is not pro-

vided, cheap imports will flood U.S. markets and the prices

of U.S. goods—along with the wages of U.S. workers—will

be pulled down. That is, the domestic living standards in

the United States will be reduced.

This argument can be rebutted at several levels. The

logic of the argument suggests that it is not mutually ben-

eficial for rich and poor persons to trade with one another.

However, that is not the case. A low- income farmworker

may pick lettuce or tomatoes for a rich landowner, and

both may benefit from the transaction. And both U.S.

consumers and Chinese workers gain when they “trade” a

pair of athletic shoes priced at $30 as opposed to a similar

shoe made in the United States for $60.

Also, recall that gains from trade are based on com-

parative advantage, not on absolute advantage. Look back

at Figure 18.1 , where we supposed that the United States

and Brazil had labor forces of exactly the same size. Not-

ing the positions of the production possibilities curves,

observe that U.S. labor can produce more of either good.

Thus, it is more productive. Because of this greater pro-

ductivity, we can expect wages and living standards to be

higher for U.S. labor. Brazil’s less productive labor will re-

ceive lower wages.

The cheap foreign labor argument suggests that, to

maintain its standard of living, the United States should

not trade with low-wage Brazil. What if it does not trade

with Brazil. Will wages and living standards rise in the

United States as a result? No. To obtain coffee, the

United States will have to reallocate a portion of its

labor from its efficient wheat industry to its inefficient

coffee industry. As a result, the average productivity of

U.S. labor will fall, as will real wages and living stan-

dards. The labor forces of both countries will have

diminished standards of living because without special-

ization and trade they will have less output available to

them. Compare column 4 with column 1 in Table 18.1

or points A ⬘ and B ⬘ with A and B in Figure 18.2 to con-

firm this point.

Trade Adjustment Assistance

A nation’s comparative advantage in the production of a

certain product is not forever fixed. As national economies

evolve, the size and quality of their labor forces may change,

the volume and composition of their capital stocks may

shift, new technologies may develop, and even the quality of

mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 354mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 354 9/15/06 4:04:04 PM9/15/06 4:04:04 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 18

International Trade

355

land and the quantity of natural resources may be altered.

As these changes take place, the relative efficiency with

which a nation can produce specific goods will also change.

Also, new trade agreements can suddenly leave formerly

protected industries highly vulnerable to major disruption

or even collapse.

Shifts in patterns of comparative advantage and removal

of trade protection can hurt specific groups of workers. For

example, the erosion of the United States’ once strong com-

parative advantage in steel has caused production plant

shutdowns and layoffs in the U.S. steel industry. The textile

and apparel industries in the United States face similar

difficulties. Clearly, not everyone wins from free trade (or

freer trade). Some workers lose.

The Trade Adjustment Assistance Act of 2002 in-

troduced some new, novel elements to help those hurt by

shifts in international trade patterns. The law provides

cash assistance (beyond unemployment insurance) for up

to 78 weeks for workers displaced by imports or plant re-

locations abroad. To obtain the assistance, workers must

participate in job searches, training programs, or remedial

education. Also provided are relocation allowances to help

displaced workers move geographically to new jobs within

the United States. Refundable tax credits for health insur-

ance serve as payments to help workers maintain their in-

surance coverage during the retraining and job search

period. Workers who are 50 years of age or older are eli-

gible for “wage insurance,” which replaces some of the

difference in pay (if any) between their old and new jobs.

Trade adjustment assistance not only helps workers hurt

by international trade but also helps create the political

support necessary to reduce trade barriers and export sub-

sidies. For both reasons, many economists support it.

But not all observers are fans of trade adjustment as-

sistance. Loss of jobs from imports or plant relocations

abroad is only a small fraction (about 3 percent in recent

years) of total job loss in the economy each year. Many

workers also lose their jobs because of changing patterns

of demand, changing technology, bad management, and

other dynamic aspects of a market economy. Some critics

ask, “What makes losing one’s job to international trade

worthy of such special treatment, compared to losing one’s

job to, say, technological change?” Economists can find no

totally satisfying answer.

Offshoring

Not only are some U.S. jobs lost because of international

trade, but some are lost because of globalization of re-

source markets. In recent years U.S. firms have found the

outsourcing of work abroad increasingly profitable. Econ-

omists call this business activity offshoring: shifting work

previously done by American workers to workers located

in other nations. Offshoring is not a new practice but

traditionally has involved components for U.S. manufac-

turing goods. For example, Boeing has long offshored the

production of major airplane parts for its “American”

aircraft.

Recent advances in computer and communications

technology have enabled U.S. firms to offshore service

jobs such as data entry, book composition, software cod-

ing, call-center operations, medical transcription, and

claims processing to countries such as India. Where off-

shoring occurs, some of the value added in the production

process accrues to foreign countries rather than the

United States. So part of the income generated from the

production of U.S. goods is paid to foreigners, not to

American workers.

Offshoring is a major burden on Americans who lose

their jobs, but it is not necessarily bad for the overall

economy. Offshoring simply reflects a growing specializa-

tion and international trade in services. That trade has

been made possible by recent trade agreements and new

information and communication technologies. Like trade

in goods, trade in services reflects comparative advantage

and is beneficial to both trading parties. Moreover, the

United States has a sizable trade surplus with other

nations in services. The U.S. gains by specializing in

high-valued services such as transportation services, ac-

counting services, legal services, and advertising services,

where it still has a comparative advantage. It then “trades”

to obtain lower-valued services such as call-center and

data entry work, for which comparative advantage has

gone abroad.

Offshoring also increases the demand for complemen-

tary jobs in the United States. Jobs that are close substi-

tutes for existing U.S. jobs are lost, but complementary

jobs in the United States are expanded. For example, the

lower price of writing software code in India may mean a

lower cost of software sold in the United States and

abroad. That, in turn, may create more jobs for U.S.-based

workers such as software designers, marketers, and dis-

tributors. Moreover, the offshoring may encourage do-

mestic investment and expansion of firms in the United

States by reducing their production costs and keeping

them competitive worldwide. In some instances, “offshor-

ing jobs” may equate to “importing competitiveness.” En-

tire firms that might otherwise disappear abroad may

remain profitable in the United States only because they

can offshore some of their work.

mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 355mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 355 9/15/06 4:04:05 PM9/15/06 4:04:05 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART SIX

International Economics

356

The World Trade Organization

As indicated in Chapter 5, the Uruguay Round of 1993

established the World Trade Organization (WTO) . In

2006, the WTO, which oversees trade agreements and

rules on disputes relating to them, had 149 member

nations. It also provides forums for further rounds of trade

negotiations. The ninth and latest round of negotiations—

the Doha Round —was launched in Doha, Qatar, in late

2001. (The trade rounds occur over several years in sev-

eral geographic venues and are named after the city or

country of origination.) The negotiations are aimed at

further reducing tariffs and quotas, as well as agricultural

subsidies that distort trade. One of this chapter’s questions

asks you to update the progress of the Doha Round (or,

alternatively, the Doha Development Agenda) via an

Internet search.

As a symbol of trade liberalization and global capitalism,

the WTO has become a target of a variety of protest groups.

This chapter’s Last Word examines some of the reason for

the protests, and we strongly suggest that you read it.

QUICK REVIEW 18.3

• A tariff on a product increases its price, reduces its

consumption, increases its domestic production, reduces its

imports, and generates tariff revenue for government; an

import quota does the same, except a quota generates

revenue for foreign producers rather than for the

government imposing the quota.

• Most rationales for trade protections are special-interest

requests that, if followed, would create gains for protected

industries and their workers at the expense of greater losses

for the economy.

• The Trade Adjustment Assistance Act of 2002 is designed to

help some of the workers hurt by shifts in international trade

patterns.

• Offshoring is a major burden on American workers who lose

their jobs, but not necessarily negative for the overall

American economy.

Last

Word

The WTO Protests

Various Protest Groups Have Angrily Targeted the

World Trade Organization (WTO). What Is the

Source of All the Noise and Commotion?

The WTO became known to the general public in November 1999,

when tens of thousands of people took part in sometimes violent

demonstrations in Seattle. Since then, international WTO meetings

have drawn large numbers of angry demonstrators. The groups in-

volved include some labor unions (which fear loss of jobs and labor

protections), environmental groups (which oppose environmental

degradation), socialists (who dislike capitalism and multinational cor-

porations), and a few anarchists (who detest government authority

of any kind). Dispersed within the crowds are other, smaller groups

such as European farmers who fear the WTO will threaten their

livelihoods by reducing agricultural tariffs and farm subsidies.

The most substantive WTO issues involve labor protections

and environmental standards. Labor unions in industrially advanced

countries (hereafter, “advanced countries”) would like the interna-

tional trade rules to include such labor standards as collective bar-

gaining rights, minimum wages, workplace safety standards, and

prohibitions of child labor. Such rules are fully consistent with the

long-standing values and objectives of unions. But there is a hitch.

Imposing labor standards on low-income developing countries

(hereafter, “developing countries”) would raise labor and produc-

tion costs in those nations. The higher costs in the developing

countries would raise the relative price of their goods and make

them less competitive with goods produced in the advanced

countries (which already meet the labor standards). So the trade

rules would increase the demands for products and workers in

the advanced countries and reduce them in the developing

countries. Union workers in the advanced countries would

benefit; consumers in the advanced countries and workers in the

developing countries would be harmed. The trade standards would

contribute to poverty in the world’s poorest nations.

Not surprisingly, the developing countries say “thanks, but no

thanks” to the protesters’ pleas for labor standards. Instead, they

want the advanced countries to reduce or eliminate tariffs on goods

imported from the developing countries. That would expand the

demand for developing countries’ products and workers, boosting

developing countries’ wages. As living standards in the developing

countries rise, those countries then can afford to devote more of

their annual productivity advances to improved working conditions.

The 149-nation WTO points out that its mandate is to liberalize

trade through multilateral negotiation, not to set labor standards

for each nation. That should be left to the countries themselves.

356

mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 356mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 356 9/15/06 4:04:05 PM9/15/06 4:04:05 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 18

International Trade

357

Economists suggest that protesters channel their efforts to sup-

porting activities of the International Labour Organization (ILO),

which strives to improve wages and working conditions worldwide.

Demonstrators might also help local groups bring political pressure

on individual nations to improve their labor protections as their

standards of living rise.

Environmental standards

are the second substantive

WTO issue. Critics are con-

cerned that trade liberaliza-

tion will encourage more

activities that degrade sensi-

tive forests, fisheries, and

mining lands and contribute

to air, water, and solid-waste

pollution. Critics would like

the WTO to establish trade

rules that set minimum envi-

ronmental standards for the

member nations. The WTO

nations respond that environ-

mental standards are outside

the mandate of the WTO and must be established by the individual

nations via their own political processes.

Moreover, imposing such standards on developing countries

may simply provide competitive cost advantages to companies in

the advanced countries. As with labor standards, that will simply

slow economic growth and prolong poverty in the developing

countries. Studies show that economic growth and rising living

standards are strongly associated with greater environmental pro-

tections. In the early phases of their development, low-income de-

veloping nations typically choose to

trade off some environmental dam-

age to achieve higher real wages. But

studies show that the tradeoff is usu-

ally reversed once standards of living

rise beyond threshold levels.

Labor standards and environ-

mental protections are worthy

objectives. But impeding efforts to lib-

eralize trade may be an ineffective—

even detrimental—way to achieve

them. Reductions in tariffs and imped-

iments to investment increase pro-

ductivity, output, and incomes

worldwide. The higher living standards

enable developing and developed

nations alike to “buy” more protec-

tions for labor and the environment. Strong, sustained economic

growth typically results not only in more goods and services but

also in more socially desirable and environmentally sensitive

production methods.

Summary

1. The United States leads the world in the combined volume of

exports and imports. Other major trading nations are Germany,

Japan, the western European nations, and the Asian economies

of China, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore.

2. World trade is based on three considerations: the uneven

distribution of economic resources among nations, the fact

that efficient production of various goods requires particu-

lar techniques or combinations of resources, and the differ-

entiated products produced among nations.

3. Mutually advantageous specialization and trade are possible

between any two nations if they have different domestic op-

portunity-cost ratios for any two products. By specializing

on the basis of comparative advantage, nations can obtain

larger real incomes with fixed amounts of resources. The

terms of trade determine how this increase in world output

is shared by the trading nations. Increasing (rather than

constant) opportunity costs limit specialization and trade.

4. A nation’s export supply curve shows the quantities of a

product the nation will export at world prices that exceed

the domestic price (the price in a closed, no-international-

trade economy). A nation’s import demand curve reveals the

quantities of a product it will import at world prices below

the domestic price.

5. In a two-nation model, the equilibrium world price and the

equilibrium quantities of exports and imports occur where

one nation’s export supply curve intersects the other nation’s

import demand curve.

6. Trade barriers take the form of protective tariffs, quotas,

nontariff barriers, and “voluntary” export restrictions. Sup-

ply and demand analysis reveals that protective tariffs and

quotas increase the prices and reduce the quantities de-

manded of the affected goods. Sales by foreign exporters di-

minish; domestic producers, however, gain higher prices and

enlarged sales. Consumer losses from trade restrictions

greatly exceed producer and government gains, creating an

efficiency loss to society.

7. The strongest arguments for protection are the infant in-

dustry and military self-sufficiency arguments. Most other

arguments for protection are interest-group appeals or rea-

soning fallacies that emphasize producer interests over con-

sumer interests or stress the immediate effects of trade

barriers while ignoring long-run consequences.

357

mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 357mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 357 9/15/06 4:04:05 PM9/15/06 4:04:05 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART SIX

International Economics

358

8. The Trade Adjustment Assistance Act of 2002 provides cash

assistance, education and training benefits, health care subsi-

dies, and wage subsidies (for persons age 50 or older) to quali-

fied workers displaced by imports or plant relocations abroad.

9. Offshoring is the practice of shifting work previously done

by Americans to workers located in other nations. While

offshoring reduces some U.S. jobs, it lowers production

costs, expands sales, and therefore may create other U.S.

jobs. Less than 3 percent of all job losses in the United

States each year result from imports, offshoring, and plant

relocations to abroad.

10. In 2006 the World Trade Organization (WTO) consisted

of 149 member nations. The WTO oversees trade agree-

ments among the members, resolves disputes over the rules,

and periodically meets to discuss and negotiate further trade

liberalization. In 2001 the WTO initiated a new round of

trade negotiations in Doha, Qatar. By 2006 the Doha Round

(or Doha Development Agenda) was still in progress.

11. As a symbol of global capitalism, the WTO has become a

target of considerable protest. The controversy surrounding

the WTO is the subject of this chapter’s Last Word. Most

economists are concerned that tying trade liberalization to a

host of other issues such as environmental and labor stan-

dards will greatly delay or block further trade liberalization.

Such liberalization is one of the main sources of higher liv-

ing standards worldwide.

Terms and Concepts

labor-intensive goods

land-intensive goods

capital-intensive goods

opportunity-cost ratio

principle of comparative advantage

terms of trade

trading possibilities line

gains from trade

world price

domestic price

export supply curve

import demand curve

equilibrium world price

tariffs

revenue tariff

protective tariff

import quota

nontariff barrier (NTB)

voluntary export restriction (VER)

strategic trade policy

dumping

Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act

Trade Adjustment Assistance Act

offshoring

World Trade Organization (WTO)

Doha Round

Study Questions

1. Quantitatively, how important is international trade to the

United States relative to other nations?

2. Distinguish among land-, labor-, and capital-intensive

commodities, citing one nontextbook example of each.

What role do these distinctions play in explaining interna-

tional trade? What role do distinctive products, unrelated to

cost advantages, play in international trade?

3. Suppose nation A can produce 80 units of X by using all its

resources to produce X or 60 units of Y by devoting all its re-

sources to Y. Comparable figures for nation B are 60 units

of X and 60 units of Y. Assuming constant costs, in which

product should each nation specialize? Why? What are the

limits of the terms of trade?

4.

KEY QUESTION To the right are hypothetical production

possibilities tables for New Zealand and Spain. Each coun-

try can produce apples and plums.

Plot the production possibilities data for each of the two

countries separately. Referring to your graphs, answer the

following:

a. What is each country’s cost ratio of producing plums

and apples.

b. Which nation should specialize in which product?

Production Alternatives

Product A B C D

Apples 0 20 40 60

Plums 15 10 5 0

New Zealand’s Production Possibilities Table

(Millions of Bushels)

Production Alternatives

Product R S T U

Apples 0 20 40 60

Plums 60 40 20 0

Spain’s Production Possibilities Table

(Millions of Bushels)

c. Show the trading possibilities lines for each nation if the

actual terms of trade are 1 plum for 2 apples. (Plot these

lines on your graph.)

d. Suppose the optimum product mixes before specializa-

tion and trade were alternative B in New Zealand and

mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 358mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 358 9/15/06 4:04:06 PM9/15/06 4:04:06 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 18

International Trade

359

alternative S in Spain. What would be the gains from

specialization and trade?

5. “The United States can produce X more efficiently than

can Great Britain. Yet we import X from Great Britain.”

Explain.

6.

KEY QUESTION Refer to Figure 3.6, page 54. Assume that

the graph depicts the U.S. domestic market for corn. How

many bushels of corn, if any, will the United States export or

import at a world price of $1, $2, $3, $4, and $5? Use this in-

formation to construct the U.S. export supply curve and im-

port demand curve for corn. Suppose the only other

corn-producing nation is France, where the domestic price is

$4. Which country will export corn; which will import it?

7.

KEY QUESTION Draw a domestic supply and demand dia-

gram for a product in which the United States does not have

a comparative advantage. What impact do foreign imports

have on domestic price and quantity? On your diagram

show a protective tariff that eliminates approximately one-

half of the assumed imports. What are the price-quantity

effects of this tariff on ( a ) domestic consumers, ( b ) domestic

producers, and ( c ) foreign exporters? How would the effects

of a quota that creates the same amount of imports differ?

8. “The potentially valid arguments for tariff protection are

also the most easily abused.” What are those arguments?

Why are they susceptible to abuse? Evaluate the use of arti-

ficial trade barriers, such as tariffs and import quotas, as a

means of achieving and maintaining full employment.

9. Evaluate the following statements:

a. Protective tariffs reduce both the imports and the ex-

ports of the nation that levies tariffs.

b. The extensive application of protective tariffs destroys

the ability of the international market system to allocate

resources efficiently.

c. Unemployment in some industries can often be reduced

through tariff protection, but by the same token ineffi-

ciency typically increases.

d. Foreign firms that “dump” their products onto the U.S.

market are in effect providing bargains to the country’s

citizens.

e. In view of the rapidity with which technological ad-

vance is dispersed around the world, free trade will

inevitably yield structural maladjustments, unemploy-

ment, and balance-of-payments problems for industri-

ally advanced nations.

f. Free trade can improve the composition and efficiency

of domestic output. Competition from Volkswagen,

Toyota, and Honda forced Detroit to make a compact

car, and foreign imports of bottled water forced

American firms to offer that product.

g. In the long run, foreign trade is neutral with respect to

total employment.

10. Suppose Japan agreed to a voluntary export restriction

(VER) that reduced U.S. imports of Japanese steel by

10 percent. What would be the likely short-run effects of

that VER on the U.S. and Japanese steel industries? If this

restriction were permanent, what would be its long-run ef-

fects in the two nations on ( a ) the allocation of resources,

( b ) the volume of employment, ( c ) the price level, and ( d ) the

standard of living?

11. What forms do trade adjustment assistance take in the

United States? How does such assistance promote support

for free trade agreements? Do you think workers who lose

their jobs because of changes in trade laws deserve special

treatment relative to workers who lose their jobs because of

other changes in the economy, say, changes in patterns of

government spending?

12. What is offshoring of white-collar service jobs, and how

does it relate to international trade? Why has it recently in-

creased? Why do you think more than half of all the off-

shored jobs have gone to India? Give an example (other

than that in the textbook) of how offshoring can eliminate

some U.S. jobs while creating other U.S. jobs.

13. What is the WTO and how does it relate to international

trade? How many nations belong to the WTO? (Update the

number given in this book at www.wto.org .) What did the

Uruguay Round (1994) of WTO trade negotiations accom-

plish? What is the name of the current WTO round of trade

negotiations?

14.

LAST WORD What are the main concerns of the WTO

protesters? What problems, if any, arise when too many ex-

traneous issues are tied to efforts to liberalize trade?

Web-Based Questions

1. TRADE LIBERALIZATION—THE WTO Go to the Web site

of the World Trade Organization ( www.wto.org ) to re-

trieve the latest news from the WTO. List and summarize

three recent news items relating to the WTO.

2.

THE U.S. INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMISSION—

WHAT IS IT AND WHAT DOES IT DO? Go to www.usitc.

gov to determine the duties of the U.S. International Trade

Commission (USITC). How does this organization differ

from the World Trade Organization (question 13)? Go to

the “Information Center” and find News Releases. Identify

and briefly describe three USITC “determinations” relating

to charges of unfair international trade practices that harm

U.S. producers.

mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 359mcc73082_ch18_338-359.indd 359 9/15/06 4:04:06 PM9/15/06 4:04:06 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

Exchange Rates, the Balance of

Payments, and Trade Deficits

If you take a U.S. dollar to the bank and ask to exchange it for U.S. currency, you will get a puzzled

look. If you persist, you may get a dollar’s worth of change: One U.S. dollar can buy exactly one U.S.

dollar. But on April 25, 2006, for example, 1 U.S. dollar could buy 2353 Colombian pesos, 1.34

Australian dollars, .56 British pounds, 1.13 Canadian dollars, .80 European euros, 114.82 Japanese

yen, or 11.15 Mexican pesos. What explains this seemingly haphazard array of exchange rates?

In Chapter 18 we examined comparative advantage as the underlying economic basis of world

trade and discussed the effects of barriers to free trade. Now we introduce the highly important

monetary or financial aspects of international trade.

IN THIS CHAPTER YOU WILL LEARN:

• How currencies of different nations are exchanged

when international transactions take place.

• About the balance sheet the United States uses to

account for the international payments it makes

and receives.

• How exchange rates are determined in currency

markets.

• The difference between flexible exchange rates and

fixed exchange rates.

• The causes and consequences of recent record-high

U.S. trade deficits.

19

mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 360mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 360 9/15/06 3:31:50 PM9/15/06 3:31:50 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 19

Exchange Rates, the Balance of Payments, and Trade Deficits

361

Financing International Trade

One factor that makes international trade different from

domestic trade is the involvement of different national

currencies. When a U.S. firm exports goods to a Mexican

firm, the U.S. exporter wants to be paid in dollars. But the

Mexican importer possesses pesos. The importer must ex-

change pesos for dollars before the U.S. export transaction

can occur.

This problem is resolved in foreign exchange markets

(or currency markets), in which dollars can purchase

Mexican pesos, European euros, South Korean won,

British pounds, Japanese yen, or any other currency, and

vice versa. Sponsored by major banks in New York,

London, Zurich, Tokyo, and elsewhere, foreign exchange

markets facilitate exports and imports.

U.S. Export Transaction

Suppose a U.S. exporter agrees to sell $300,000 of com-

puters to a British firm. Assume, for simplicity, that the

rate of exchange—the rate at which pounds can be

exchanged for, or converted into, dollars, and vice

versa—is $2 for £1 (the actual exchange rate is about

$1.80 ⫽ 1 pound). This means the British importer must

pay the equivalent of £150,000 to the U.S. exporter to

obtain the $300,000 worth of computers. Also assume

that all buyers of pounds and dollars are in the United

States and Great Britain. Let’s follow the steps in the

transaction:

• To pay for the computers, the British buyer draws a

check for £150,000 on its checking account in a

London bank and sends it to the U.S. exporter.

• But the U.S. exporting firm must pay its bills in dol-

lars, not pounds. So the exporter sells the £150,000

check on the London bank to its bank in, say, New

York City, which is a dealer in foreign exchange. The

bank adds $300,000 to the U.S. exporter’s checking

account for the £150,000 check.

• The New York bank deposits the £150,000 in a cor-

respondent London bank for future sale to some U.S.

buyer who needs pounds.

Note this important point: U.S. exports create a foreign

demand for dollars, and the fulfillment of that demand

increases the supply of foreign currencies (pounds, in

this case) owned by U.S. banks and available to U.S.

buyers.

Why would the New York bank be willing to buy

pounds for dollars? As just indicated, the New York bank

is a dealer in foreign exchange; it is in the business of

buying (for a fee) and selling (also for a fee) one currency

for another.

U.S. Import Transaction

Let’s now examine how the New York bank would sell

pounds for dollars to finance a U.S. import (British export)

transaction. Suppose a U.S. retail firm wants to import

£150,000 of compact discs produced in Britain by a hot new

musical group. Again, let’s track the steps in the transaction:

• The U.S. importer purchases £150,000 at the $2 ⫽ £1

exchange rate by writing a check for $300,000 on its

New York bank. Because the British exporting firm

wants to be paid in pounds rather than dollars, the

U.S. importer must exchange dollars for pounds,

which it does by going to the New York bank and

purchasing £150,000 for $300,000. (Perhaps the U.S.

importer purchases the same £150,000 that the

New York bank acquired from the U.S. exporter.)

• The U.S. importer sends its newly purchased check

for £150,000 to the British firm, which deposits it in

the London bank.

Here we see that U.S. imports create a domestic demand

for foreign currencies (pounds, in this case), and the

fulfillment of that demand reduces the supplies of foreign

currencies (again, pounds) held by U.S. banks and available

to U.S. consumers.

The combined export and import transactions bring

one more point into focus. U.S. exports (the computers)

make available, or “earn,” a supply of foreign currencies

for U.S. banks, and U.S. imports (the compact discs) cre-

ate a demand for those currencies. In a broad sense, any

nation’s exports finance or “pay for” its imports. Exports

provide the foreign currencies needed to pay for imports.

Postscript: Although our examples are confined to

exporting and importing goods, demand for and supplies

of pounds also arise from transactions involving services

and the payment of interest and dividends on foreign

investments. The United States demands pounds not only

to buy imports but also to buy insurance and transporta-

tion services from the British, to vacation in London, to

pay dividends and interest on British investments in the

United States, and to make new financial and real invest-

ments in Britain. (Key Question 2)

The Balance of Payments

A nation’s balance of payments is the sum of all the

transactions that take place between its residents and the

residents of all foreign nations. Those transactions include

exports and imports of goods, exports and imports of

services, tourist expenditures, interest and dividends re-

ceived or paid abroad, and purchases and sales of financial

or real assets abroad. The U.S. Commerce Department’s

mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 361mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 361 9/15/06 3:31:54 PM9/15/06 3:31:54 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART SIX

International Economics

362

Bureau of Economic Analysis compiles the balance-of-

payments statement each year. The statement shows all

the payments a nation receives from foreign countries and

all the payments it makes to them. It shows “flows” of in-

payments to and outpayments from the United States.

Table 19.1 is a simplified balance-of-payments state-

ment for the United States in 2005. Let’s take a close look

at this accounting statement to see what it reveals about

U.S. international trade and finance. To help our explana-

tion, we divide the single balance-of-payments account

into two components: the current account and the capital

and financial account.

Current Account

The top portion of Table 19.1 summarizes U.S. trade in

currently produced goods and services and is called the cur-

rent account. Items 1 and 2 show U.S. exports and imports

of goods (merchandise) in 2005. U.S. exports have a plus (⫹)

sign because they are a credit; they earn and make available

foreign exchange in the United States. As you saw in the

preceding section, any export-type transaction that obligates

foreigners to make “inpayments” to the United States gen-

erates supplies of foreign currencies in the U.S. banks.

U.S. imports have a minus (⫺) sign because they are a

debit; they reduce the stock of foreign currencies in the

United States. Our earlier discussion of trade financing

indicated that U.S. imports obligate the United States to

make “outpayments” to the rest of the world that reduce

available supplies of foreign currencies held by U.S. banks.

Balance on Goods Items 1 and 2 in Table 19.1

reveal that in 2005 U.S. goods exports of $893 billion did

not earn enough foreign currencies to finance U.S. goods

imports of $1675 billion. A country’s balance of trade on

goods is the difference between its exports and its imports

of goods. If exports exceed imports, the result is a surplus

on the balance of goods. If imports exceed exports, there is

a trade deficit on the balance of goods. We note in item 3

that in 2005 the United States incurred a trade deficit on

goods of $782 billion.

Balance on Services The United States exports

not only goods, such as airplanes and computer software,

but also services, such as insurance, consulting, travel, and

brokerage services, to residents of foreign nations. Item 4

in Table 19.1 shows that these service “exports” totaled

TABLE 19.1 The U.S. Balance of Payments, 2005 (in Billions)

Current account

(1) U.S. goods exports $⫹893

(2) U.S. goods imports ⫺1675

(3) Balance on goods $⫺782

(4) U.S. exports of services ⫹380

(5) U.S. imports of services ⫺322

(6) Balance on services ⫹58

(7) Balance on goods and services ⫺724

(8) Net investment income ⫹2

(9) Net transfers ⫺83

(10) Balance on current account ⴚ805

Capital and financial account

Capital account

(11) Balance on capital account ⫺6

Financial account

(12) Foreign purchases of assets in the United States ⫹1298*

(13) U.S. purchases of assets abroad ⫺487*

(14) Balance on financial account ⫹811

(15) Balance on capital and financial account ⴙ 805

$ 0

*Includes one-half of a $10 billion statistical discrepancy that is listed in the capital account.

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, www.bea.gov/. Preliminary 2005 data.

The export and import data are on a “balance-of-payment basis,” and usually vary from the data on export

and imports reported in the National Income and Product Accounts.

mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 362mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 362 9/15/06 3:31:54 PM9/15/06 3:31:54 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 19

Exchange Rates, the Balance of Payments, and Trade Deficits

363

$380 billion in 2005 and are a credit (thus the ⫹ sign).

Item 5 indicates that the United States “imports” similar

services from foreigners; those service imports were $322

billion in 2005 and are a debit (thus the ⫺ sign). So the

balance on services (item 6) in 2005 was $58 billion.

The balance on goods and services shown as item 7

is the difference between U.S. exports of goods and

services (items 1 and 4) and U.S. imports of goods and

services (items 2 and 5). In 2005, U.S. imports of goods

and services exceeded U.S. exports of goods and services

by $724 billion. So a trade deficit (or “unfavorable balance

of trade”) occurred. In contrast, a trade surplus (or

“favorable balance of trade”) occurs when exports of goods

and services exceed imports of goods and services. (Global

Perspective 19.1 shows U.S. trade deficits and surpluses

with selected nations.)

Balance on Current Account Item 8, net invest-

ment income, represents the difference between (1) the inter-

est and dividend payments foreigners paid the United States

for the use of exported U.S. capital and (2) the interest and

dividends the United States paid for the use of foreign capi-

tal invested in the United States. Observe that in 2005 U.S.

net investment income was a positive $2 billion worth of

foreign currencies.

Item 9 shows net transfers, both public and private, be-

tween the United States and the rest of the world. Included

here is foreign aid, pensions paid to U.S. citizens living

abroad, and remittances by immigrants to relatives abroad.

These $83 billion of transfers are net U.S. outpayments that

decrease available supplies of foreign exchange. They are,

in a sense, the exporting of goodwill and the importing of

“thank-you notes.”

By adding all transactions in the current account, we

obtain the balance on current account shown in item 10.

In 2005 the United States had a current account deficit of

$805 billion. This means that the U.S. current account

transactions (items 2, 5, 8, and 9) created outpayments of

foreign currencies from the United States greater than the

inpayments of foreign currencies to the United States.

Capital and Financial Account

The second account within the overall balance-of-payments

account is the capital and financial account, which consists

of two separate accounts: the capital account and the financial

account.

Capital Account The capital account is a “net”

account (one that can be either ⫹ or ⫺) that mainly

measures debt forgiveness. Line 11 tells us that in 2005

Americans forgave $6 billion more of debt owed to them

by foreigners than foreigners forgave debt owed to them

by Americans. The ⫺ sign indicates a debit; it is an “on-

paper” outpayment by the net amount of debt forgiven.

Financial Account The financial account summa-

rizes the purchase or sale of real or financial assets and the

corresponding flows of monetary payments that accom-

pany them. For example, a foreign firm may buy a real

asset, say, an office building in the United States, or a

financial asset, for instance, a U.S. government security.

Both kinds of transaction involve the “export” of the

ownership of U.S. assets from the United States in return

for inpayments of foreign currency. As indicated in line

12, these “exports” of ownership of assets are designated

foreign purchases of assets in the United States. They have

a ⫹ sign because, like exports of U.S. goods and services,

they represent inpayments of foreign currencies.

Conversely, a U.S. firm may buy, say, a hotel chain

(real asset) in a foreign country or some of the common

stock (financial asset) of a foreign firm. Both transactions

involve the “import” of the ownership of the real or

financial assets to the United States and are paid for by

outpayments of foreign currencies. These “imports” are

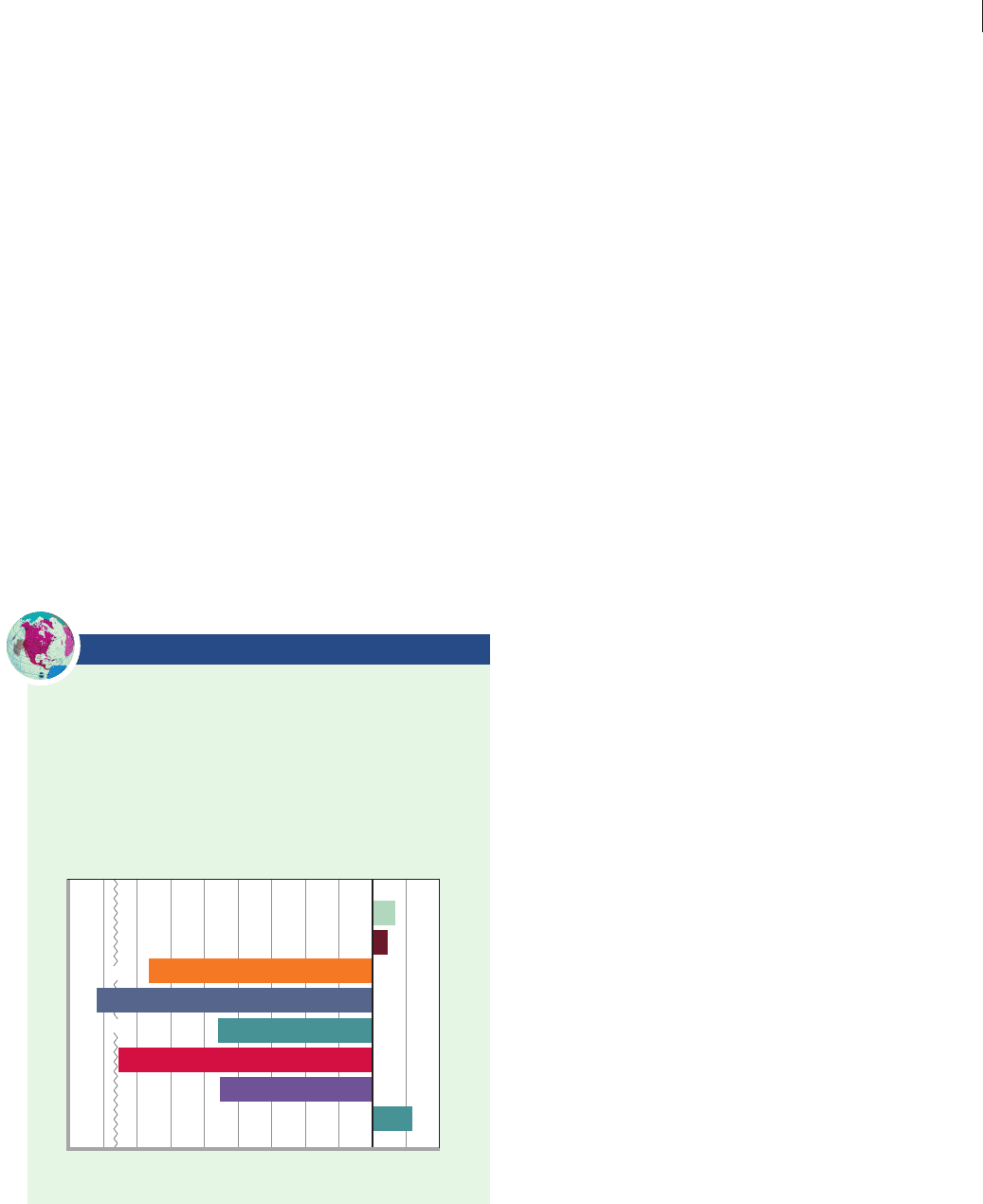

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE 19.1

Source: Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis,

www.bea.gov/ .

U.S. Trade Balances in Goods and Services,

Selected Nations, 2004

The United States has large trade deficits in goods and services

with several nations, in particular, China, Japan, and Canada.

Netherlands

China

Germany

Mexico

Canada

Australia

Japan

Belgium

–160 –70 –60 –50 –40 –30 –20 –10 0

Billions of U.S. Dollars

Goods and Services Deficit Goods and Services

Surplus

+10 +20

mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 363mcc73082_ch19_360-380.indd 363 9/15/06 3:31:54 PM9/15/06 3:31:54 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES