McConnell С., Campbell R. Macroeconomics: principles, problems, and policies, 17th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER 14

Interest Rates and Monetary Policy

273

For example, an increase in the money supply from

$125 billion to $150 billion ( S

m 1

to S

m 2

) will reduce the

interest rate from 10 to 8 percent, as indicated in

Figure 14.5 a, and will boost investment from $15 billion

to $20 billion, as shown in Figure 14.5 b. This $5 billion

increase in investment will shift the aggregate demand

curve rightward by more than the increase in investment

because of the multiplier effect. If the economy’s MPC is

.75, the multiplier will be 4, meaning that the $5 billion

increase in investment will shift the AD curve rightward

by $20 billion ( 4 $5) at each price level. Specifically,

aggregate demand will shift from AD

1

to AD

2

, as shown

in Figure 14.5 c. This rightward shift in the aggregate

demand curve will eliminate the negative GDP gap by

increasing GDP from Q

1

to the full-employment GDP

of Q

f .

1

Column 1 in Table 14.3 summarizes the chain of

events associated with an expansionary monetary policy.

Effects of a Restrictive Monetary

Policy

Now let’s assume that the money supply is $175 billion

( S

m 3

) in Figure 14.2 a. This results in an interest rate of

6 percent, investment spending of $25 billion, and

aggregate demand AD

3

. As you can see in Figure 14.5 c,

we have depicted a positive GDP gap of Q

3

Q

f

and

demand-pull inflation. Aggregate demand AD

3

is exces-

sive relative to the economy’s full-employment level of

real output Q

f

. To rein in spending, the Fed will institute

a restrictive monetary money policy.

The Federal Reserve Board will direct Federal Re-

serve Banks to undertake some combination of the fol-

lowing actions: (1) Sell government securities to banks

and the public in the open market, (2) increase the legal

reserve ratio, and (3) increase the discount rate. Banks

then will discover that their reserves are below those re-

quired and that the Federal funds rate has increased. So

they will need to reduce their checkable deposits by re-

fraining from issuing new loans as old loans are paid

back. This will shrink the money supply and increase the

interest rate. The higher interest rate will discourage in-

vestment, lowering aggregate demand and restraining

demand-pull inflation.

If the Fed reduces the money supply from $175 bil-

lion to $150 billion ( S

m 3

to S

m 2

in Figure 14.5 a), the in-

terest rate will rise from 6 to 8 percent and investment

will decline from $25 billion to $20 billion ( Figure

14.5 b). This $5 billion decrease in investment, bolstered

by the multiplier process, will shift the aggregate de-

mand curve leftward from AD

3

to AD

2

. For example, if

the MPC is .75, the multiplier will be 4 and the aggre-

gate demand curve will shift leftward by $20 bil-

lion ( 4 $5 billion of investment) at each price level.

This leftward shift of the aggregate demand curve will

eliminate the excessive spending and thus the demand-

pull inflation. In the real world, of course, the goal will

be to stop inflation—that is, to halt further increases in

the price level—rather than to actually drive down the

price level.

2

Column 2 in Table 14.3 summarizes the cause-effect

chain of a tight money policy.

1

To keep things simple, we assume that the increase in real GDP does

not increase the demand for money. In reality, the transactions demand

for money would rise, slightly dampening the decline in the interest rate

shown in Figure 14.5a.

2

Again, we assume for simplicity that the decrease in nominal GDP does

not feed back to reduce the demand for money and thus the interest rate.

In reality, this would occur, slightly dampening the increase in the inter-

est rate shown in Figure 14.5a.

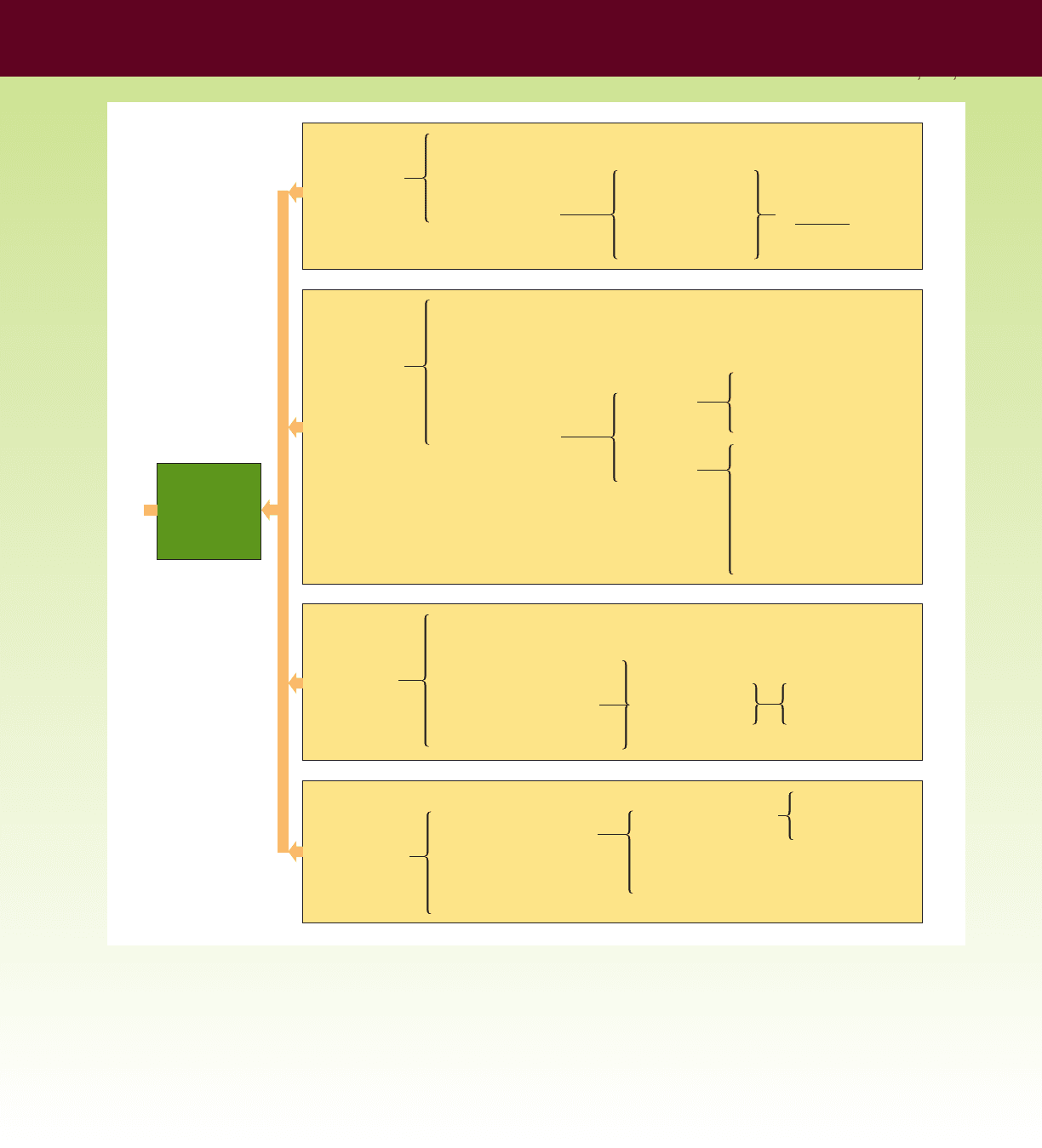

TABLE 14.3 Monetary Policies for Recession and Inflation

(1) (2)

Expansionary Restrictive

Monetary Policy Monetary Policy

Problem: unemployment Problem: inflation

and recession

Federal Reserve buys bonds, Federal Reserve sells bonds,

lowers reserve ratio, or lowers increases reserve ratio, or

the discount rate increases the discount rate

Excess reserves increase Excess reserves decrease

Federal funds rate falls Federal funds rate rises

Money supply rises Money supply falls

Interest rate falls Interest rate rises

Investment spending Investment spending

increases decreases

Aggregate demand Aggregate demand

increases decreases

Real GDP rises Inflation declines

⏐

⏐

↓

⏐

⏐

↓

⏐

⏐

↓

⏐

⏐

↓

⏐

⏐

↓

⏐

⏐

↓

⏐

⏐

↓

⏐

⏐

↓

⏐

⏐

↓

⏐

⏐

↓

⏐

⏐

↓

⏐

⏐

↓

⏐

⏐

↓

⏐

⏐

↓

⏐

⏐

↓

⏐

⏐

↓

mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 273mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 273 9/1/06 3:46:39 PM9/1/06 3:46:39 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART FOUR

Money, Banking, and Monetary Policy

274

Monetary Policy: Evaluation

and Issues

Monetary policy has become the dominant component of

U.S. national stabilization policy. It has two key advan-

tages over fiscal policy:

• Speed and flexibility.

• Isolation from political pressure.

Compared with fiscal policy, monetary policy can be

quickly altered. Recall that congressional deliberations

may delay the application of fiscal policy for months. In

contrast, the Fed can buy or sell securities from day to

day and thus affect the money supply and interest rates

almost immediately.

Also, because members of the Fed’s Board of

Governors are appointed and serve 14-year terms, they

are relatively isolated from lobbying and need not worry

about retaining their popularity with voters. Thus, the

Board, more readily than Congress, can engage in

politically unpopular policies (higher interest rates) that

may be necessary for the long-term health of the economy.

Moreover, monetary policy is a subtler and more politi-

cally conservative measure than fiscal policy. Changes in

government spending directly affect the allocation of re-

sources, and changes in taxes can have extensive political

ramifications. Because monetary policy works more subtly,

it is more politically palatable.

Recent U.S. Monetary Policy

In the early 1990s, the Fed’s expansionary monetary policy

helped the economy recover from the 1990–1991 reces-

sion. The expansion of GDP that began in 1992 continued

through the rest of the decade. By 2000 the U.S. unem-

ployment rate had declined to 4 percent—the lowest rate

in 30 years. To counter potential inflation during that

strong expansion, in 1994 and 1995, and then again in

early 1997, the Fed reduced reserves in the banking sys-

tem to raise the interest rate. In 1998 the Fed temporarily

reversed its course and moved to a more expansionary

monetary policy to make sure that the U.S. banking sys-

tem had plenty of liquidity in the face of a severe financial

crisis in southeast Asia. The economy continued to expand

briskly, and in 1999 and 2000 the Fed, in a series of steps,

boosted interest rates to make sure that inflation remained

under control.

Significant inflation did not occur in the late 1990s. But

in the last quarter of 2000 the economy abruptly slowed.

The Fed responded by cutting interest rates by a full per-

centage point in two increments in January 2001. Despite

these rate cuts, the economy entered a recession in

March 2001. Between March 20, 2001, and August 21,

2001, the Fed cut the Federal funds rate from 5 percent to

3.5 percent in a series of steps. In the 3 months following

the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, it lowered the

Federal funds rate from 3.5 percent to 1.75 percent, and it

left the rate there until it lowered it to 1.25 percent in No-

vember 2002. Partly because of the Fed’s actions, the prime

interest rate dropped from 9.5 percent at the end of 2000 to

4.25 percent in December 2002.

Economists generally credit the Fed’s adroit use of

monetary policy as one of a number of factors that helped

the U.S. economy achieve and maintain the rare

combination of full employment, price-level stability,

and strong economic growth that occurred between 1996

and 2000. The Fed also deserves high marks for helping

to keep the recession of 2001 relatively mild, particularly

in view of the adverse economic impacts of the terrorist

attacks of September 11, 2001, and the steep stock market

drop in 2001–2002.

In 2003 the Fed left the Federal funds rate at historic

lows. But as the economy began to expand robustly in

2004, the Fed engineered a series of five separate

1

4

-percentage-point hikes in the Federal funds rate. It con-

tinued to raise the rate throughout 2005. At the end of

2005 the rate stood at 4.25 percent. The purpose of the

rate hikes was to boost the prime interest rate (7.25 per-

cent at the end of 2005) and other interest rates to make

sure that aggregate demand continued to grow at a pace

consistent with low inflation. In that regard, the Fed was

successful. (To see the latest direction of the targeted

Federals funds rate, go to the Federal Reserve’s Web site,

www.federalreserve.gov , and select Monetary Policy and

then Open Market Operations.)

Problems and Complications

Despite its recent successes in the United States, monetary

policy has certain limitations and faces real-world

complications.

Lags Recall that three elapses of time (lags)—a recogni-

tion lag, an administrative lag, and an operational lag—

hinder the timing of fiscal policy. Monetary policy faces a

similar recognition lag and also an operational lag, but it

avoids the administrative lag. Because of monthly varia-

tions in economic activity and changes in the price level,

the Fed may take a while to recognize that the economy is

receding or the rate of inflation is rising (recognition lag).

And once the Fed acts, it may take 3 to 6 months or more

for interest-rate changes to have their full impacts on in-

vestment, aggregate demand, real GDP, and the price level

mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 274mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 274 9/1/06 3:46:39 PM9/1/06 3:46:39 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 14

Interest Rates and Monetary Policy

275

(operational lag). These two lags thus complicate the tim-

ing of monetary policy.

Cyclical Asymmetry Monetary policy may be

highly effective in slowing expansions and controlling

inflation but less reliable in pushing the economy from a

severe recession. Economists say that monetary policy

may suffer from cyclical asymmetry .

If pursued vigorously, a restrictive monetary policy

could deplete commercial banking reserves to the point

where banks would be forced to reduce the volume of loans.

That would mean a contraction of the money supply, higher

interest rates, and reduced aggregate demand. The Fed can

absorb reserves and eventually achieve its goal.

But it cannot be certain of achieving its goal when it

adds reserves to the banking system. An expansionary mon-

etary policy suffers from a “You can lead a horse to water,

but you can’t make it drink” problem. The Fed can create

excess reserves, but it cannot guarantee that the banks will

actually make the added loans and thus increase the supply

of money. If commercial banks seek liquidity and are un-

willing to lend, the efforts of the Fed will be of little avail.

Similarly, businesses can frustrate the intentions of the Fed

by not borrowing excess reserves. And the public may use

money paid to them through Fed sales of U.S. securities to

pay off existing bank loans.

Furthermore, a severe recession may so undermine

business confidence that the investment demand curve

shifts to the left and frustrates an expansionary monetary

policy. That is what happened in Japan in the 1990s and

early 2000s. Although its central bank drove the real inter-

est rate to 0 percent, investment spending remained low

and the Japanese economy stayed mired in recession. In

fact, deflation—a fall in the price level—occurred. The

Japanese experience reminds us that monetary policy is

not an assured cure for the business cycle.

In March 2003 some members of the Fed’s Open

Market Committee expressed concern about potential de-

flation in the United States if the economy remained weak.

But the economy soon began to vigorously expand, and

deflation did not occur.

“Artful Management” or

“Inflation Targeting”?

Under the leadership of Alan Greenspan, the Fed and

FOMC artfully managed the money supply to avoid

escalating inflation, on the one hand, and deep recession

and deflation, on the other. The emphasis was on “risk

management” and achieving a multiple set of objectives:

primarily to maintain price stability but also to smooth the

business cycle, maintain high levels of employment, and

promote strong economic growth. Greenspan and the

FOMC used their best judgment (and, some suggest,

Greenspan’s personal intuition) to determine appropriate

changes in monetary policy. But Greenspan retired in

early 2006 and was replaced by Ben Bernanke as chairman

of the Federal Reserve Board. Does Bernanke—or anyone

for that matter—have Greenspan’s intuition?

Some economists are concerned that this “artful

management” may have been unique to Greenspan and

CONSIDER THIS . . .

Pushing on a String

In the late 1990s and early

2000s, the central bank of

Japan used an expansionary

monetary policy to reduce

real interest rates to zero.

Even with “interest-free”

loans available, most consum-

ers and businesses did not

borrow and spend more.

Japan’s economy continued to sputter in and out of recession.

The Japanese circumstance illustrates the possible asymme-

try of monetary policy, which economists have likened to “pull-

ing versus pushing on a string.” A string may be effective at

pulling something back to a desirable spot, but it is ineffective

at pushing it toward a desired location.

So it is with monetary policy, say some economists. Mone-

tary policy can readily pull the aggregate demand curve to the

left, reducing demand-pull inflation. There is no limit on how

much a central bank can restrict a nation’s money supply and

hike interest rates. Eventually, a sufficiently restrictive mone-

tary policy will reduce aggregate demand and inflation.

But during severe recession, participants in the economy

may be highly pessimistic about the future. If so, an expan-

sionary monetary policy may not be able to push the aggre-

gate demand curve to the right, increasing real GDP. The

central bank can produce excess reserves in the banking sys-

tem by reducing the reserve ratio, lowering the discount rate,

and purchasing government securities. But commercial banks

may not be able to find willing borrowers for those excess

reserves, no matter how low interest rates fall. Instead of

borrowing and spending, consumers and businesses may be

more intent on reducing debt and increasing saving in prepa-

ration for expected worse times ahead. If so, monetary policy

will be ineffective. Using it under those circumstances will be

much like pushing on a string.

mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 275mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 275 9/1/06 3:46:40 PM9/1/06 3:46:40 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

276

276

key

graph

1. All else equal, an increase in domestic resource availability will:

a. increase input prices, reduce aggregate supply, and increase

real output.

b. raise labor productivity, reduce interest rates, and lower the

international value of the dollar.

c. increase net exports, increase investment, and reduce

aggregate demand.

d. reduce input prices, increase aggregate supply, and increase

real output.

2. All else equal, an expansionary monetary policy during a

recession will:

a. lower the interest rate, increase investment, and reduce net

exports.

b. lower the interest rate, increase investment, and increase

aggregate demand.

c. increase the interest rate, increase investment, and reduce

net exports.

d. reduce productivity, aggregate supply, and real output.

QUICK QUIZ 14.6

Levels of

output,

employment,

income, and

prices

Exchange

rates

1. Land

2. Labor

3. Capital

4. Entrepreneurial

ability

1.

2.

Input prices

1. Domestic

resource

prices

Productivity

1. Education

and training

2. Technology

3. Quantity of

capital

4. Management

2. Prices of

imported

resources

3. Market

power

Antitrust

Labor law

Business taxes

and subsidies

Government

regulation

1.

2.

Legal-institutional

environment

Aggregate

supply

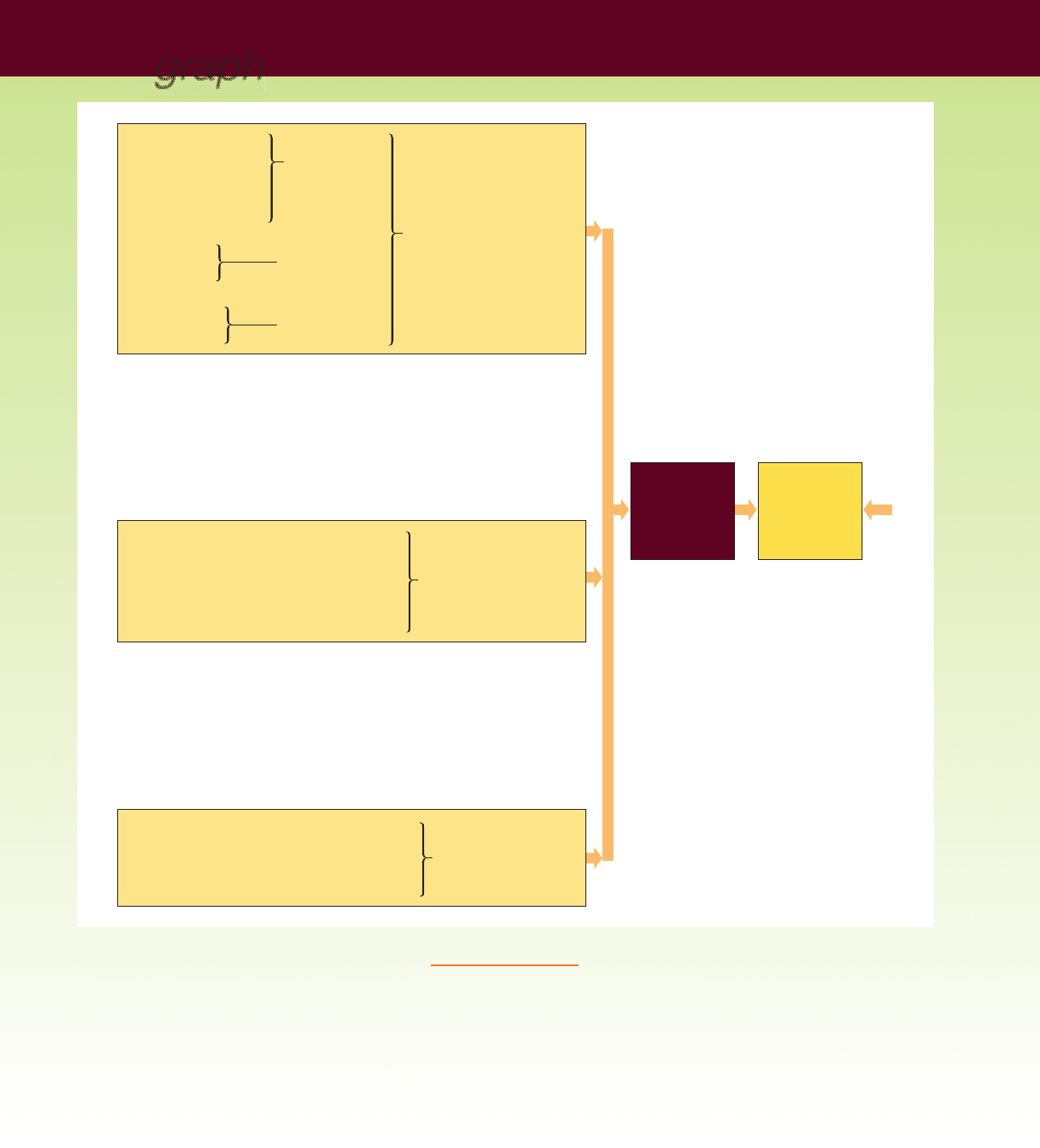

FIGURE 14.6 The AD-AS theory of the

price level, real output, and stabilization

policy. This figure integrates the various components

of macroeconomic theory and stabilization policy.

Determinants that either constitute public policy or are

strongly influenced by public policy are shown in red.

mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 276mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 276 9/1/06 3:46:40 PM9/1/06 3:46:40 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 14

Interest Rates and Monetary Policy

277

277

Consumption

(C

a

)

1. Level of GDP

2. Consumption

schedule

Multiplier =

1

1 – MPC

Investment

(I

g

)

1. Expected rate of return

Transactions

demand

Asset demand

Net export

spending

(X

n

)

1. Imports

a. Domestic GDP

leve l

b. Exchange rates

2. Exports

a. GDP levels abroad

b. Exchange rates

Government

spending

(G )

1. Federal

2. State and local

Tax levels

Supply of

money

Tax levels

Interest rate

Expansionary monetary policy

Buy securities

Lower reserve ratio

Lower discount rate

Restrictive monetary policy

Sell securities

Raise reserve ratio

Raise discount rate

Interest rate

Fiscal policy

Monetary

policy

Deficit or surplus

Discretionary

action

Automatic

stabilizers

Fiscal policy

Size

Method of

finance or

disposition

a.

b. Nonstabilizing and

noneconomic

considerations

1.

2.

1.

2.

1.

2.

1. Price levels

2.

1.

2.

3.

1.

2.

3.

Demand for

money

a. Technological change

b. Capital costs

c. Stock of capital goods

d. Expectations; “business

confidence”

e.

2.

1. Wealth

2. Price level

3. Expectations

4. Indebtedness

5.

Aggregate

demand

Answers: 1. d; 2. b; 3. a; 4. a

3. A personal income tax cut, combined with a reduction in

corporate income and excise taxes, would:

a. increase consumption, investment, aggregate demand, and

aggregate supply.

b. reduce productivity, raise input prices, and reduce aggregate

supply.

c. increase government spending, reduce net exports, and

increase aggregate demand.

d. increase the supply of money, reduce interest rates, increase

investment, and expand real output.

4. An appreciation of the dollar would:

a. reduce the price of imported resources, lower input prices,

and increase aggregate supply.

b. increase net exports and aggregate demand.

c. increase aggregate supply and aggregate demand.

d. reduce consumption, investment, net export spending, and

government spending.

mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 277mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 277 9/1/06 3:46:40 PM9/1/06 3:46:40 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART FOUR

Money, Banking, and Monetary Policy

278

that someone less insightful may not be as successful.

These economists, including Bernanke, say it might be

beneficial to replace or combine the artful management

of monetary policy with so-called inflation targeting —

the annual statement of a target range of inflation, say,

1 to 2 percent, for the economy over some period such

as 2 years. The Fed would then undertake monetary

policy to achieve that goal, explaining to the public how

each monetary action fits within its overall strategy. If

the Fed missed its target, it would need to explain what

went wrong. So inflation targeting would increase the

“transparency” (openness) of monetary policy and

increase Fed accountability. Several countries, including

Canada, New Zealand, Sweden, and the United King-

dom, have adopted inflation targeting.

Proponents of inflation targeting say that, along with

increasing transparency and accountability, it would focus

the Fed on what should be its main mission: controlling

inflation and keeping deflation from occurring. They say

that an explicit commitment to price-level stability will

create more certainty for households and firms about

future product and input prices and create greater output

stability. In the advocates’ view, setting and meeting an in-

flation target is the single best way for the Fed to achieve

its important subsidiary goals of full employment and

strong economic growth.

But some economists are relatively unconvinced by

the arguments for inflation targeting. They say that the

overall success of the countries that have adopted the

policy has come at a time in which inflationary pres-

sures, in general, have been weak. The truer test will oc-

cur under more severe economic conditions. Critics of

inflation targeting say that it assigns too narrow a role

for the Fed. They do not want to limit the Fed’s discre-

tion to adjust the money supply and interest rates to

smooth the business cycle, independent of meeting a

specific inflation target. Those who oppose inflation tar-

geting say the recent U.S. monetary policy owes its success

to adherence to sound principles of monetary policy, not

simply to special intuition. In fact, the Fed has kept the rate

of inflation generally lower than have the central banks in

nations that use inflation targeting. In view of this overall

success, ask critics, why saddle the Fed with an explicit in-

flation target? (Key Question 8)

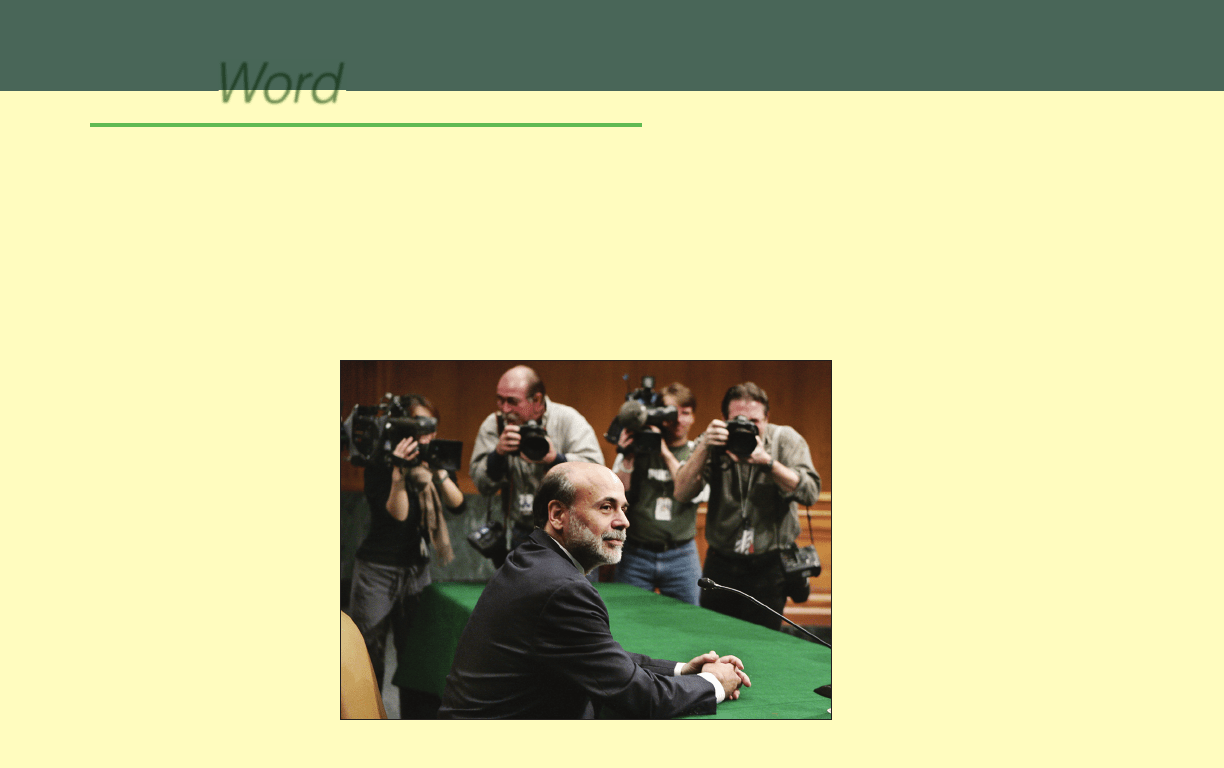

Last

Word

Normally calm, Bernanke took one look at the car and started

to sweat. This would be hard to fix—it was an economy car:

“What’s the problem?” asked Bernanke.

“It’s been running beautifully for over 6 years now,” said

the customer. “But recently it’s been acting sluggish.”

“These cars are tricky,” said Bernanke. “We can always

loosen a few screws, as long as

you don’t mind the side effects.”

“What side effects?” asked

the customer.

“Nothing at first,” said

Bernanke. “We won’t even

know if the repairs have worked

for at least a year. After that, ei-

ther everything will be fine, or

your car will accelerate wildly

and go totally out of control.”

“Just as long as it doesn’t

stall,” said the customer. “I

hate that.”

The Popular Press Often Describes the Federal

Reserve Board and Its Chair (Ben Bernanke) in

Colorful Terms :

The Federal Reserve Board leads a very dramatic life, or so it

seems when one reads journalistic accounts of its activities. It

loosens or tightens reins while

riding herd on a rambunctious

economy, goes to the rescue of

an embattled dollar, tightens

spigots on credit . . . you get

the picture. For the Fed, life is

a metaphor.

The Fed as Mechanic The

Fed sometimes must roll up its

sleeves and adjust the economic

machinery. The Fed spends a

lot of time tightening things,

loosening things, or debating

about whether to tighten or

loosen.

Imagine a customer taking

his car into Bernanke’s Garage:

For the Fed, Life Is a Metaphor

278

mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 278mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 278 9/1/06 3:46:41 PM9/1/06 3:46:41 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 14

Interest Rates and Monetary Policy

279

279

QUICK REVIEW 14.4

• The Fed is engaging in an expansionary monetary policy

when it increases the money supply to reduce interest rates

and increase investment spending and real GDP; it is

engaging in a restrictive monetary policy when it reduces the

money supply to increase interest rates and reduce

investment spending and inflation.

• The main strengths of monetary policy are (a) speed and

flexib ility and (b) political acceptability; its main weaknesses

are (a) time lags and (b) potential ineffectiveness during

severe recession.

• The Fed’s “artful management” of monetary policy has been

highly successful in recent years, but some economists

contend that this approach should be replaced or combined

with explicit inflation targeting.

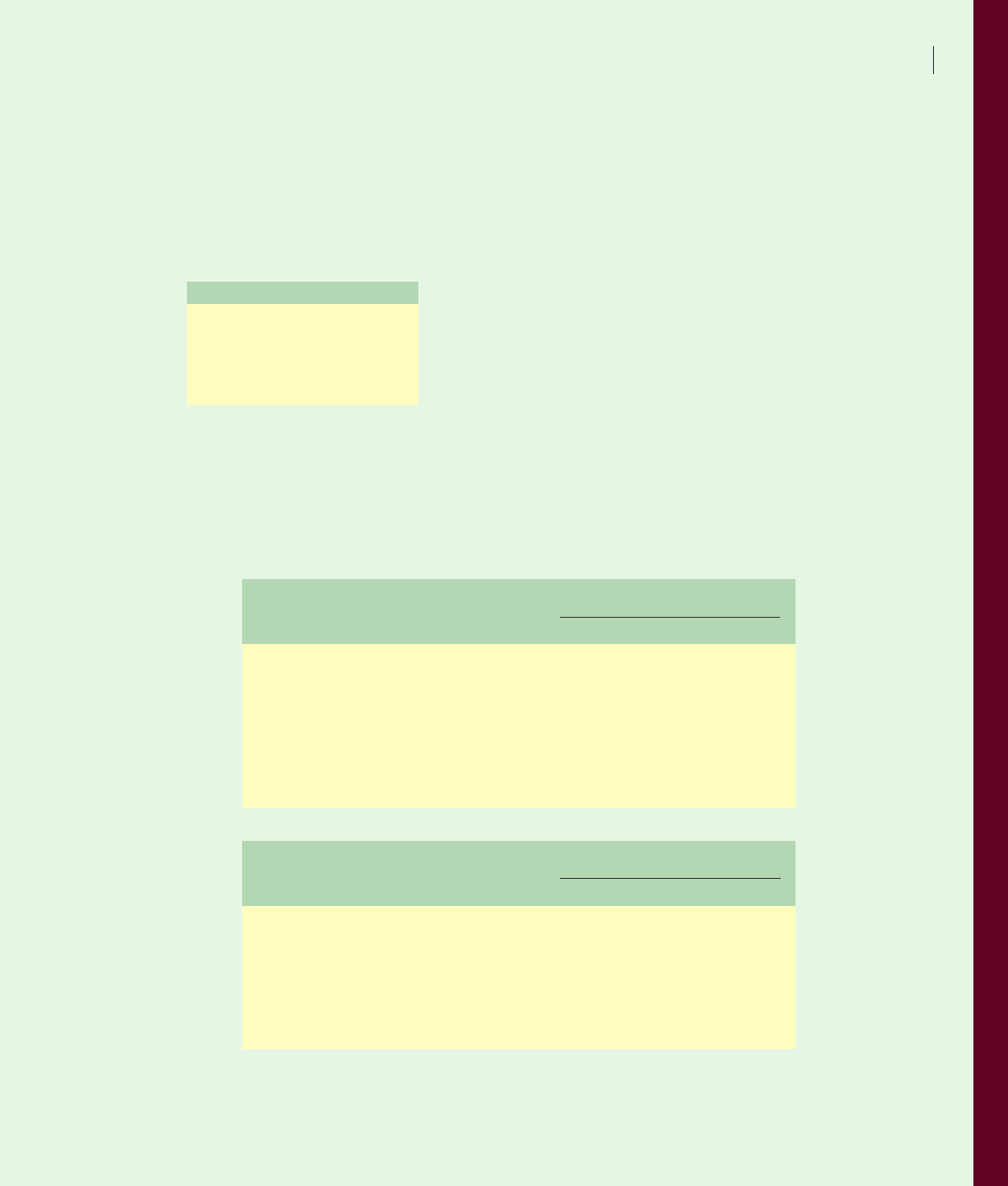

The “Big Picture”

Figure 14.6 (Key Graph) on pages 276 and 277 brings

together the analytical and policy aspects of macroeco-

nomics discussed in this and the eight preceding chapters.

key

graph

Source: Paul Hellman, “Greenspan and the Feds: Captains Courageous,”

The Wall Street Journal, Jan. 31, 1991, p. 18. Reprinted with permission

of The Wall Street Journal, © 1990 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

All rights reserved. Updated by text authors.

The Fed as Warrior The Fed must fight inflation. But can it

wage a protracted war? There are only seven Fed governors,

including Bernanke—not a big army:

Gen. Bernanke sat in the war room plotting strategy. You

never knew where the enemy would strike next—producer

prices, retail sales, factory payrolls, manufacturing inventories.

Suddenly, one of his staff officers burst into the room:

“Straight from the Western European front, sir—the dollar is

under attack by the major industrial nations.”

Bernanke whirled around toward the big campaign map.

“We’ve got to turn back this assault!” he said.

“Yes sir. ”The officer turned to go.

“Hold it!” Bernanke shouted. Suddenly, his mind reeled with

conflicting data. A strong dollar was good for inflation, right? Yes,

but it was bad for the trade deficit. Or was it the other way

around? Attack? Retreat? Macroeconomic forces were closing in.

“Call out the Reserve!” he told the officer.

“Uh . . . we are the Reserve,” the man answered.

The Fed as the Fall Guy Inflation isn’t the only tough

customer out there. The Fed must also withstand pressure from

administration officials who are regularly described as “leaning

heavily” on the Fed to ease up and relax. This always sounds

vaguely threatening:

Ben Bernanke was walking down a deserted street late one

night. Suddenly a couple of thugs wearing pin-stripes and wing-

tips cornered him in a dark alley.

“What do you want?” Bernanke asked.

“Just relax,” said one.

“How can I relax?” asked Bernanke. “I’m in a dark alley

talking to thugs.”

“You know what we mean,” said the other. “Ease up on the

Federal funds rate—or else.”

“Or else what?” asked Bernanke.

“Don’t make us spell it out. Let’s just say that if anything

unfortunate happens to the gross domestic product, I’m holding

you personally responsible.”

“Yeah,” added the other.“A recession could get real painful.”

The Fed as Cosmic Force The Fed may be a cosmic force. After

all, it does satisfy the three major criteria—power, mystery, and a

New York office. Some observers even believe the Fed can control

the stock market, either by action, symbolic action, anticipated ac-

tion, or non-action. But saner heads realize this is ridiculous—the

market has always been controlled by sunspots.

I wish we could get rid of all these romantic ideas about the

Federal Reserve. If you want to talk about the Fed, keep it

simple. Just say the Fed is worried about the money. This is

something we all can relate to.

This “big picture” shows how the many concepts and

principles discussed relate to one another and how they

constitute a coherent theory of the price level and real

output in a market economy.

Study this diagram and you will see that the levels of

output, employment, income, and prices all result from

the interaction of aggregate supply and aggregate demand.

The items shown in red relate to public policy.

mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 279mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 279 9/1/06 3:46:42 PM9/1/06 3:46:42 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART FOUR

Money, Banking, and Monetary Policy

280

1. The goal of monetary policy is to help the economy achieve

price stability, full employment, and economic growth.

2. The total demand for money consists of the transactions de-

mand and asset demand for money. The amount of money

demanded for transactions varies directly with the nominal

GDP; the amount of money demanded as an asset varies

directly with the interest rate. The market for money com-

bines the total demand for money with the money supply to

determine equilibrium interest rates.

3. Interest rates and bond prices are inversely related.

4. The three available instruments of monetary policy are (a)

open-market operations, (b) the reserve ratio, and (c) the

discount rate.

5. The Federal funds rate is the interest rate that banks charge

one another for overnight loans of reserves. The prime in-

terest rate is the benchmark rate that banks use as a refer-

ence rate for a wide range of interest rates on short-term

loans to businesses and individuals.

6. The Fed adjusts the Federal funds rate to a level appropriate for

economic conditions. In an expansionary monetary policy, it

purchases securities from commercial banks and the general

public to inject reserves into the banking system. This lowers

the Federal funds rate to the targeted level and also reduces

other interest rates (such as the prime rate). In a restrictive

monetary policy, the Fed sells securities to commercial banks

and the general public via open-market operations. Conse-

quently, reserves are removed from the banking system, and

the Federal funds rate and other interest rates rise.

7. Monetary policy affects the economy through a complex

cause-effect chain: (a) Policy decisions affect commercial

bank reserves; (b) changes in reserves affect the money sup-

ply; (c) changes in the money supply alter the interest rate;

(d) changes in the interest rate affect investment; (e) changes

in investment affect aggregate demand; (f) changes in ag-

gregate demand affect the equilibrium real GDP and the

price level. Table 14.3 draws together all the basic ideas rel-

evant to the use of monetary policy.

8. The advantages of monetary policy include its flexibility

and political acceptability. In the recent past, the Fed has

adroitly used monetary policy to hold inflation in check as

the economy boomed, to limit the depth of the recession

of 2001, and to promote economic recovery. Today, nearly

all economists view monetary policy as a significant

stabilization tool.

9. Monetary policy has two major limitations and potential

problems: (a) Recognition and operation lags complicate

the timing of monetary policy. (b) In a severe recession, the

reluctance of firms to borrow and spend on capital goods

may limit the effectiveness of an expansionary monetary

policy.

10. Some economists recommend that the United States follow

the lead of several other nations, including Canada and the

United Kingdom, in replacing or combining the “artful

management” of monetary policy with inflation targeting .

Opponents of this idea believe it may unduly reduce the

Fed’s flexibility in smoothing business cycles.

monetary policy

interest

transactions demand

asset demand

total demand for money

open-market operations

reserve ratio

discount rate

Federal funds rate

expansionary monetary policy

prime interest rate

restrictive monetary policy

Taylor rule

cyclical asymmetry

inflation targeting

Terms and Concepts

Study Questions

1. KEY QUESTION What is the basic determinant of ( a ) the trans-

actions demand and ( b ) the asset demand for money? Explain

how these two demands can be combined graphically to deter-

mine total money demand. How is the equilibrium interest

rate in the money market determined? Use a graph to show

the impact of an increase in the total demand for money on

the equilibrium interest rate (no change in money supply).

Use your general knowledge of equilibrium prices to explain

why the previous interest rate is no longer sustainable.

2.

KEY QUESTION Assume that the following data character-

ize a hypothetical economy: money supply $200 billion;

quantity of money demanded for transactions $150 billion;

quantity of money demanded as an asset $10 billion at

12 percent interest, increasing by $10 billion for each

2-percentage-point fall in the interest rate.

a. What is the equilibrium interest rate? Explain.

b. At the equilibrium interest rate, what are the quantity

of money supplied, the total quantity of money

Summary

mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 280mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 280 9/1/06 3:46:42 PM9/1/06 3:46:42 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 14

Interest Rates and Monetary Policy

281

demanded, the amount of money demanded for transac-

tions, and the amount of money demanded as an asset?

3.

KEY QUESTION Suppose a bond with no expiration date

has a face value of $10,000 and annually pays a fixed amount

of interest of $800. Compute and enter in the spaces pro-

vided in the accompanying table either the interest rate that

the bond would yield to a bond buyer at each of the bond

prices listed or the bond price at each of the interest yields

shown. What generalization can be drawn from the com-

pleted table?

5.

KEY QUESTION In the accompanying table you will find

consolidated balance sheets for the commercial banking sys-

tem and the 12 Federal Reserve Banks. Use columns 1

through 3 to indicate how the balance sheets would read af-

ter each of transactions a to c is completed. Do not cumulate

your answers; that is, analyze each transaction separately,

starting in each case from the figures provided. All accounts

are in billions of dollars.

a. A decline in the discount rate prompts commercial

banks to borrow an additional $1 billion from the

Federal Reserve Banks. Show the new balance-sheet

figures in column 1 of each table.

b. The Federal Reserve Banks sell $3 billion in securities

to members of the public, who pay for the bonds with

checks. Show the new balance-sheet figures in column 2

of each table.

c. The Federal Reserve Banks buy $2 billion of securities

from commercial banks. Show the new balance-sheet

figures in column 3 of each table.

d. Now review each of the above three transactions, asking

yourself these three questions: (1) What change, if any,

took place in the money supply as a direct and immedi-

ate result of each transaction? (2) What increase or

decrease in the commercial banks’ reserves took place in

each transaction? (3) Assuming a reserve ratio of

Consolidated Balance Sheet:

All Commercial Banks

(1) (2) (3)

Assets:

Reserves . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . $ 33 _______ _______ _______

Securities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60 _______ _______ _______

Loans . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60 _______ _______ _______

Liabilities and net worth:

Checkable deposits . . . . . . . . . . . . . $150 _______ _______ _______

Loans from the Federal

Reserve Banks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 _______ _______ _______

Consolidated Balance Sheet:

The 12 Federal Reserve Banks

(1) (2) (3)

Assets:

Securities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . $60 _______ _______ _______

Loans to commercial banks . . . . . . . 3 _______ _______ _______

Liabilities and net worth:

Reserves of commercial banks . . . . . $33

Treasury deposits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 _______ _______ _______

Federal Reserve Notes . . . . . . . . . . 27 _______ _______ _______

Bond Price Interest Yield, %

$ 8,000 ______

_______ 8.9

$10,000 ______

$11,000 ______

_______ 6.2

4. Use commercial bank and Federal Reserve Bank balance

sheets to demonstrate the impact of each of the following

transactions on commercial bank reserves:

a. Federal Reserve Banks purchase securities from banks.

b. Commercial banks borrow from Federal Reserve Banks.

c. The Fed reduces the reserve ratio.

mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 281mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 281 9/1/06 3:46:42 PM9/1/06 3:46:42 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART FOUR

Money, Banking, and Monetary Policy

282

20 percent, what change in the money-creating poten-

tial of the commercial banking system occurred as a re-

sult of each transaction?

6. What is the basic objective of monetary policy? What are

the major strengths of monetary policy? Why is monetary

policy easier to conduct than fiscal policy in a highly divided

national political environment?

7. Distinguish between the Federal funds rate and the prime

interest rate. Why is one higher than the other? Why do

changes in the two rates closely track one another?

8.

KEY QUESTION Suppose that you are a member of the

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The

economy is experiencing a sharp rise in the inflation rate.

What change in the Federal funds rate would you recom-

mend? How would your recommended change get accom-

plished? What impact would the actions have on the lending

ability of the banking system, the real interest rate, invest-

ment spending, aggregate demand, and inflation?

9. Suppose that the Federal funds rate is 4 percent and real

GDP falls 2 percent below potential GDP. Acording to the

Taylor rule, in what direction and by how much should the

Fed change the Federal funds rate?

10. Explain the links between changes in the nation’s money

supply, the interest rate, investment spending, aggregate de-

mand, and real GDP (and the price level).

11. What do economists mean when they say that monetary

policy can exhibit cyclical asymmetry? Why is this possibil-

ity significant to policymakers?

12. What is “inflation targeting,” and how does it differ from

“artful management”? What are the main benefits of infla-

tion targeting, according to its supporters? Why do many

economists think it is unnecessary or even undesirable?

13.

LAST WORD How do each of the following metaphors ap-

ply to the Federal Reserve’s role in the economy: Fed as a

mechanic; Fed as a warrior; Fed as a fall guy?

Web-Based Questions

1. CURRENT U.S. INTEREST RATES Visit the Federal Reserve’s

Web site at www.federalreserve.gov , and select Economic

Research and Data, then Statistics: Releases and Historical

Data, Selected Interest Rates (weekly), and Historical Data

to find the most recent values for the following interest

rates: the Federal funds rate, the discount rate, and the

prime interest rate. Are these rates higher or lower than

they were 3 years ago? Have they increased, decreased, or

remained constant over the past year?

2.

THE FEDERAL RESERVE ANNUAL REPORT Visit the

Federal Reserve’s Web site at www.federalreserve.gov , and

select Monetary Policy and then Monetary Policy Report to

the Congress to retrieve the current annual report (Sections

1 and 2). Summarize the policy actions of the Board of

Governors during the most recent period. In the Fed’s opin-

ion, how did the U.S. economy perform?

mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 282mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 282 9/1/06 3:46:42 PM9/1/06 3:46:42 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES