McConnell С., Campbell R. Macroeconomics: principles, problems, and policies, 17th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER 13

Money Creation

253

The answer is that reserves lost by a single bank are

not lost to the banking system as a whole. The reserves

lost by bank A are acquired by bank B. Those lost by B are

gained by C. C loses to D, D to E, E to F, and so forth.

Although reserves can be, and are, lost by individual banks

in the banking system, there is no loss of reserves for the

banking system as a whole.

An individual bank can safely lend only an amount

equal to its excess reserves, but the commercial banking

system can lend by a multiple of its excess reserves. This

contrast, incidentally, is an illustration of why it is impera-

tive that we keep the fallacy of composition (Last Word,

Chapter 1) firmly in mind. Commercial banks as a group

can create money by lending in a manner much different

from that of the individual banks in the group.

The Monetary Multiplier

The banking system magnifies any original excess reserves

into a larger amount of newly created checkable-deposit

money. The checkable-deposit multiplier, or monetary mul-

tiplier , is similar in concept to the spending-income mul-

tiplier in Chapter 8. That multiplier exists because the

expenditures of one household become some other house-

hold’s income; the multiplier magnifies a change in initial

spending into a larger change in GDP. The spending-

income multiplier is the reciprocal of the MPS (the leak-

age into saving that occurs at each round of spending).

Similarly, the monetary multiplier exists because the

reserves and deposits lost by one bank become reserves of

another bank. It magnifies excess reserves into a larger

creation of checkable-deposit money. The monetary

multiplier m is the reciprocal of the required reserve ratio

R (the leakage into required reserves that occurs at each

step in the lending process). In short,

Monetary multiplier

1

___________________

required reserve ratio

or, in symbols,

m

1

__

R

In this formula, m represents the maximum amount of

new checkable-deposit money that can be created by a

single dollar of excess reserves, given the value of R. By

multiplying the excess reserves E by m, we can find the

maximum amount of new checkable-deposit money, D ,

that can be created by the banking system. That is,

Maximum

checkable-deposit

excess

reserves

monetary

multiplier

creation

Bank

(1)

Acquired

Reserves and

Deposits

(2)

Required

Reserves

(Reserve

Ratio .2)

(3)

Excess

Reserves,

(1) (2)

(4)

Amount Bank Can

Lend; New Money

Created (3)

Bank A $ 100.00 (a

1

) $20.00 $80.00 $ 80.00 (a

2

)

Bank B 80.00 (a

3

, b

1

) 16.00 64.00 64.00 (b

2

)

Bank C 64.00 (b

3

, c

1

) 12.80 51.20 51.20 (c

2

)

Bank D 51.20 10.24 40.96 40.96

Bank E 40.96 8.19 32.77 32.77

Bank F 32.77 6.55 26.21 26.21

Bank G 26.21 5.24 20.97 20.97

Bank H 20.97 4.20 16.78 16.78

Bank I 16.78 3.36 13.42 13.42

Bank J 13.42 2.68 10.74 10.74

Bank K 10.74 2.15 8.59 8.59

Bank L 8.59 1.72 6.87 6.87

Bank M 6.87 1.37 5.50 5.50

Bank N 5.50 1.10 4.40 4.40

Other banks 21.99 4.40 17.59 17.59

Total amount of money created (sum of the amounts in column 4)

$400.00

TABLE 13.2 Expansion of the Money Supply by the Commercial Banking System

mcc26632_ch13_244-257.indd 253mcc26632_ch13_244-257.indd 253 8/31/06 4:31:20 PM8/31/06 4:31:20 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART FOUR

Money, Banking, and Monetary Policy

254

or, more simply,

D E m

In our example in Table 13.2 , R is .20, so m is 5 ( 1兾.20).

Then

D $80 5 $400

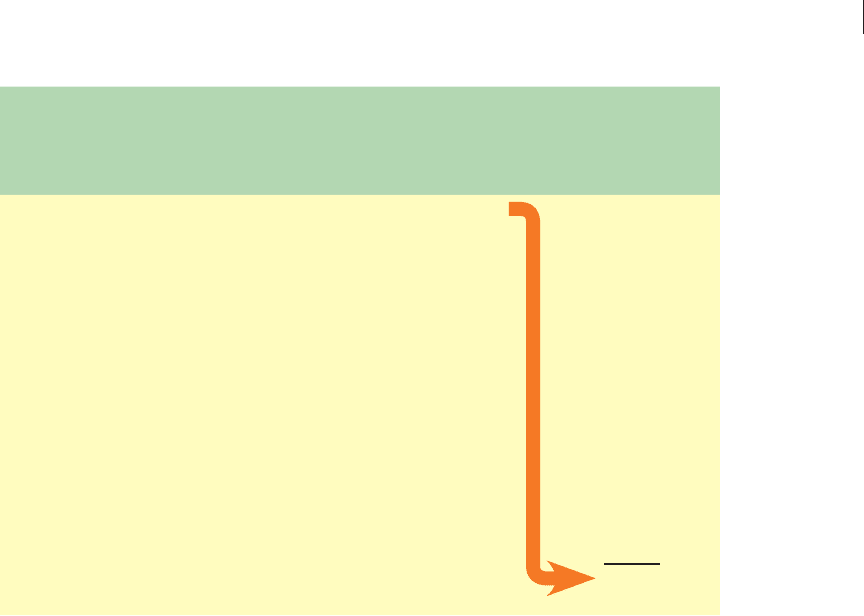

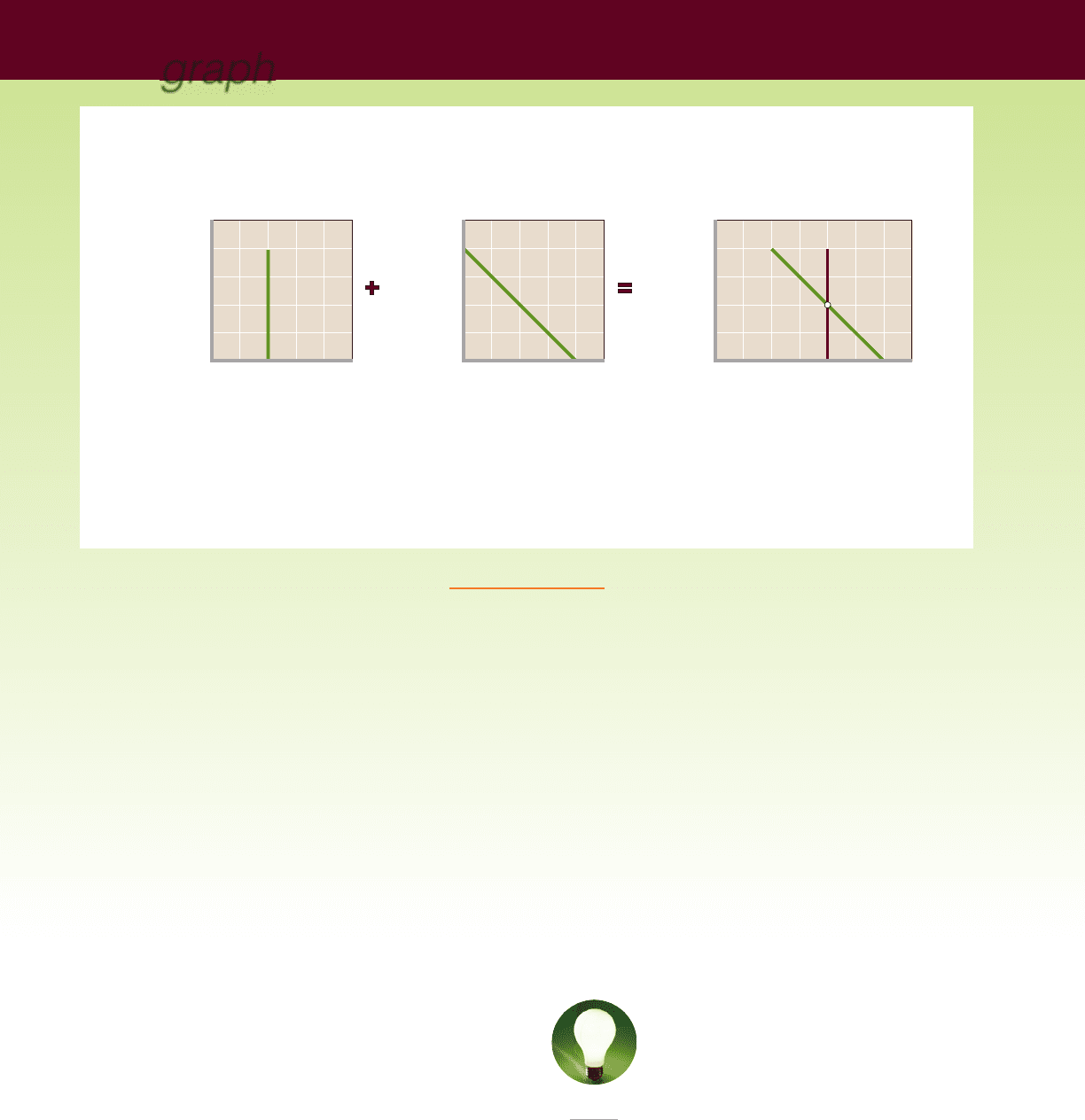

Figure 13.1 depicts the final outcome of our example

of a multiple-deposit expansion of the money supply. The

initial deposit of $100 of currency into the bank (lower

right-hand box) creates new reserves of an equal amount

(upper box). With a 20 percent reserve ra-

tio, however, only $20 of reserves are

needed to “back up” this $100 checkable

deposit. The excess reserves of $80 permit

the creation of $400 of new checkable de-

posits via the making of loans, confirming

a monetary multiplier of 5. The $100 of

new reserves supports a total supply of

money of $500, consisting of the $100 initial checkable

deposit plus $400 of checkable deposits created through

lending.

Higher reserve ratios mean lower monetary multipli-

ers and therefore less creation of new checkable-deposit

money via loans; smaller reserve ratios mean higher mon-

etary multipliers and thus more creation of new checkable-

deposit money via loans. With a high reserve ratio, say,

50 percent, the monetary multiplier would be 2 ( 1兾.5),

and in our example the banking system could create only

$100 ( $50 of excess reserves 2) of new checkable de-

posits. With a low reserve ratio, say, 5 percent, the mone-

tary multiplier would be 20 ( 1兾.05), and the banking

system could create $1900 ( $95 of excess reserves 20)

of new checkable deposits.

You might experiment with the following two

brainteasers to test your understanding of multiple credit

expansion by the banking system:

• Rework the analysis in Table 13.2 (at least three

or four steps of it) assuming the reserve ratio is

10 percent. What is the maximum amount of money

the banking system can create upon acquiring $100 in

new reserves and deposits? (The answer is not $800!)

• Suppose the banking system is loaned up and faces a

20 percent reserve ratio. Explain how it might have

to reduce its outstanding loans by $400 when a $100

cash withdrawal from a checkable-deposit account

forces one bank to draw down its reserves by $100.

(Key Question 13)

Reversibility: The Multiple

Destruction of Money

The process we have described is reversible. Just as check-

able-deposit money is created when banks make loans,

checkable-deposit money is destroyed when loans are paid

off. Loan repayment, in effect, sets off a process of multi-

ple destruction of money the opposite of the multiple cre-

ation process. Because loans are both made and paid off in

any period, the direction of the loans, checkable deposits,

and money supply in a given period will depend on the

net effect of the two processes. If the dollar amount of

loans made in some period exceeds the dollar amount of

loans paid off, checkable deposits will expand and the

money supply will increase. But if the dollar amount of

loans is less than the dollar amount of loans paid off,

checkable deposits will contract and the money supply

will decline.

FIGURE 13.1 The outcome of the money expansion

process. A deposit of $100 of currency into a checking account creates

an initial checkable deposit of $100. If the reserve ratio is 20 percent, only

$20 of reserves is legally required to support the $100 checkable deposit.

The $80 of excess reserves allows the banking system to create $400 of

checkable deposits through making loans. The $100 of reserves supports a

total of $500 of money ($100 ⴙ $400).

New reserves

$100

$20

Required

reserves

Money created

$80

Excess

reserves

$100

Initial

deposit

$400

Bank system lending

QUICK REVIEW 13.3

• A single bank in a multibank system can safely lend (create

money) by an amount equal to its excess reserves; the

banking system can lend (create money) by a multiple of its

excess reserves.

• The monetary multiplier is the reciprocal of the required

reserve ratio; it is the multiple by which the banking system

can expand the money supply for each dollar of excess reserves.

• The monetary multiplier works in both directions; it applies

to money destruction from the payback of loans as well as

the money creation from the making of loans.

W 13.2

Money creation

mcc26632_ch13_244-257.indd 254mcc26632_ch13_244-257.indd 254 8/31/06 4:31:20 PM8/31/06 4:31:20 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 13

Money Creation

255

Last

Word

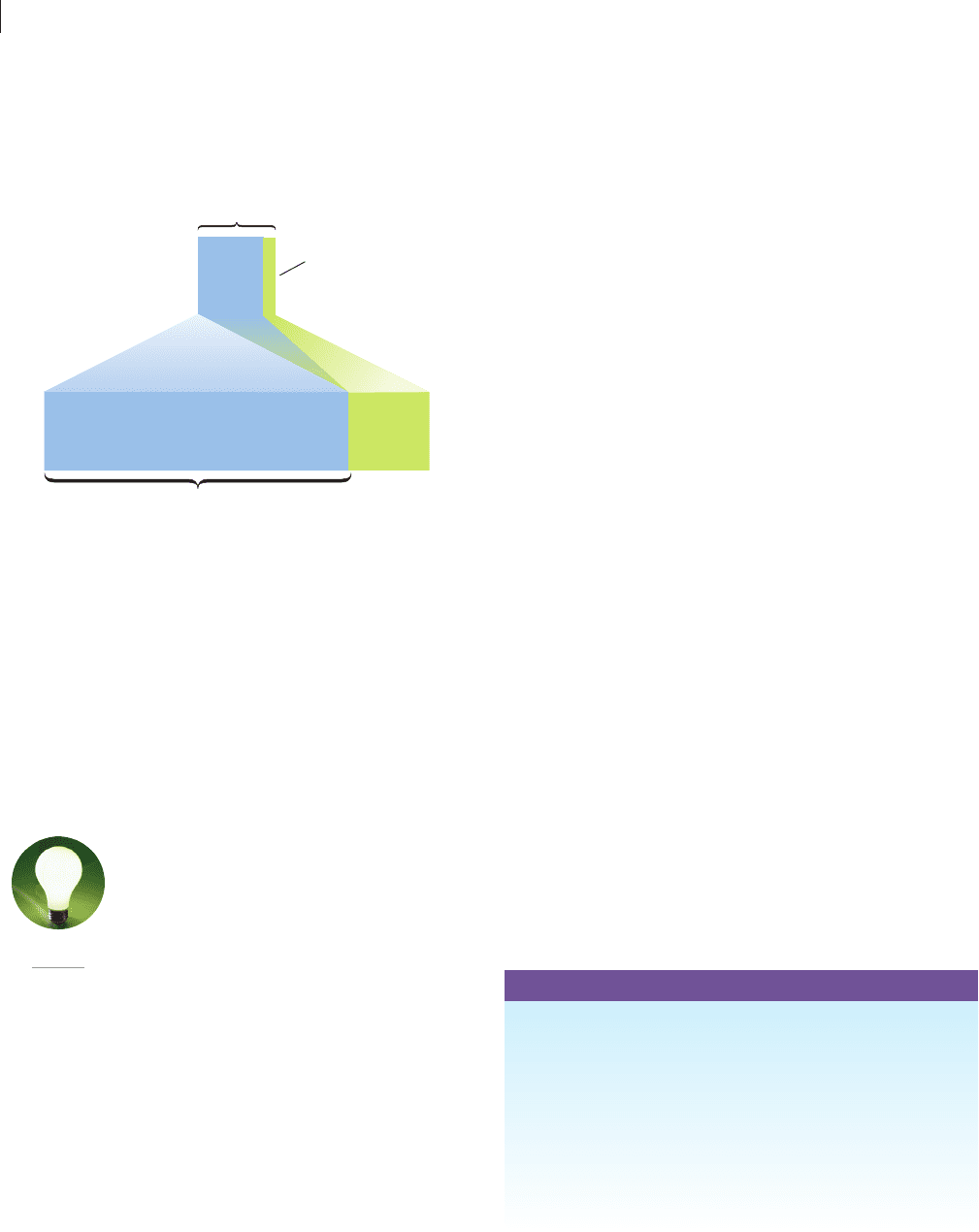

The Bank Panics of 1930 to 1933

A Series of Bank Panics in the Early 1930s Resulted

in a Multiple Contraction of the Money Supply.

In the early months of the Great Depression, before there was

deposit insurance, several financially weak banks went out of

business. As word spread that customers of those banks had lost

their deposits, a general concern arose that something similar

could happen at other banks. Depositors became frightened that

their banks did not, in fact, still have all the money they had

deposited. And, of course, in a

fractional reserve banking sys-

tem, that is the reality. Acting

on their fears, people en masse

tried to withdraw currency—

that is, to “cash out” their ac-

counts—from their banks.

They wanted to get their

money before it was all gone.

Economists liken this sort of

collective response to “herd”

or “flock” behavior. The sud-

den “run on the banks” caused

many previously financially

sound banks to declare bank-

ruptcy. More than 9000 banks

failed within 3 years.

The massive conversion of checkable deposits to currency

during 1930 to 1933 reduced the nation’s money supply. This

might seem strange, since a check written for “cash” reduces

checkable-deposit money and increases currency in the hands of

the public by the same amount. So how does the money supply

decline? Our discussion of the money-creation process provides

the answer, but now the story becomes one of money destruction.

Suppose that people collectively cash out $10 billion from

their checking accounts. As an immediate result, checkable-

deposit money declines by $10 billion, while currency held by

the public increases by $10 billion. But here is the catch: As-

suming a reserve ratio of 20 percent, the $10 billion of currency

in the banks had been supporting $50 billion of deposit money,

the $10 billion of deposits plus $40 billion created through

loans. The $10 billion withdrawal of currency forces banks to

reduce loans (and thus checkable-deposit money) by $40 billion

to continue to meet their reserve requirement. In short, a

$40 billion destruction of deposit money occurs. This is the

scenario that occurred in the early years of the 1930s.

Accompanying this multiple contraction of checkable

deposits was the banks’ “scramble for liquidity” to try to meet

further withdrawals of currency. To obtain more currency, they

sold many of their holdings of government securities to the

public. You know from this chapter that a bank’s sale of govern-

ment securities to the public,

like a reduction in loans, re-

duces the money supply. Peo-

ple write checks for the

securities, reducing their

checkable deposits, and the

bank uses the currency it ob-

tains to meet the ongoing bank

run. In short, the loss of re-

serves from the banking sys-

tem, in conjunction with the

scramble for security, reduced

the amount of checkable-de-

posit money by far more than

the increase in currency in the

hands of the public. Thus, the

money supply collapsed.

In 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt ended the bank pan-

ics by declaring a “national bank holiday,” which closed all na-

tional banks for 1 week and resulted in the federally insured

deposit program. Meanwhile, the nation’s money supply had

plummeted by 25 percent, the largest such drop in U.S. history.

This decline in the money supply contributed to the nation’s

deepest and longest depression.

Today, a multiple contraction of the money supply of the

1930–1933 magnitude is unthinkable. FDIC insurance has kept

individual bank failures from becoming general panics. Also,

while the Fed stood idly by during the bank panics of 1930 to

1933, today it would take immediate and dramatic actions to

maintain the banking system’s reserves and the nation’s money

supply. Those actions are the subject of Chapter 14.

255

mcc26632_ch13_244-257.indd 255mcc26632_ch13_244-257.indd 255 8/31/06 4:31:21 PM8/31/06 4:31:21 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART FOUR

Money, Banking, and Monetary Policy

256

1. Modern banking systems are fractional reserve systems:

Only a fraction of checkable deposits is backed by currency.

2. The operation of a commercial bank can be understood

through its balance sheet, where assets equal liabilities plus

net worth.

3. Commercial banks keep required reserves on deposit in a

Federal Reserve Bank or as vault cash. These required

reserves are equal to a specified percentage of the commer-

cial bank’s checkable-deposit liabilities. Excess reserves are

equal to actual reserves minus required reserves.

4. Banks lose both reserves and checkable deposits when

checks are drawn against them.

5. Commercial banks create money—checkable deposits, or

checkable-deposit money—when they make loans. The

creation of checkable deposits by bank lending is the most

important source of money in the U.S. economy. Money is

destroyed when lenders repay bank loans.

6. The ability of a single commercial bank to create money by

lending depends on the size of its excess reserves. Generally

speaking, a commercial bank can lend only an amount equal

to its excess reserves. Money creation is thus limited because,

in all likelihood, checks drawn by borrowers will be deposited

in other banks, causing a loss of reserves and deposits to the

lending bank equal to the amount of money that it has lent.

7. Rather than making loans, banks may decide to use excess re-

serves to buy bonds from the public. In doing so, banks merely

credit the checkable-deposit accounts of the bond sellers, thus

creating checkable-deposit money. Money vanishes when

banks sell bonds to the public, because bond buyers must draw

down their checkable-deposit balances to pay for the bonds.

8. Banks earn interest by making loans and by purchasing

bonds; they maintain liquidity by holding cash and excess

reserves. Banks having temporary excess reserves often lend

them overnight to banks that are short of required reserves.

The interest rate paid on loans in this Federal funds market

is called the Federal funds rate.

9. The commercial banking system as a whole can lend by a

multiple of its excess reserves because the system as a whole

cannot lose reserves. Individual banks, however, can lose

reserves to other banks in the system.

10. The multiple by which the banking system can lend on the

basis of each dollar of excess reserves is the reciprocal of the

reserve ratio. This multiple credit expansion process is re-

versible.

Terms and Concepts

fractional reserve banking system

balance sheet

vault cash

required reserves

reserve ratio

excess reserves

actual reserves

Federal funds rate

monetary multiplier

Study Questions

1. Why must a balance sheet always balance? What are the ma-

jor assets and claims on a commercial bank’s balance sheet?

2.

KEY QUESTION Why does the Federal Reserve require

commercial banks to have reserves? Explain why reserves

are an asset to commercial banks but a liability to the Fed-

eral Reserve Banks. What are excess reserves? How do you

calculate the amount of excess reserves held by a bank?

What is the significance of excess reserves?

3. “Whenever currency is deposited in a commercial bank,

cash goes out of circulation and, as a result, the supply of

money is reduced.” Do you agree? Explain why or why not.

4.

KEY QUESTION “When a commercial bank makes loans, it

creates money; when loans are repaid, money is destroyed.”

Explain.

5. Explain why a single commercial bank can safely lend only

an amount equal to its excess reserves but the commercial

banking system as a whole can lend by a multiple of its

excess reserves. What is the monetary multiplier, and how

does it relate to the reserve ratio?

6. Assume that Jones deposits $500 in currency into her

checkable-deposit account in First National Bank. A half-

hour later Smith obtains a loan for $750 at this bank. By how

256

Summary

Assets Liabilities and net worth

(1) (2) (1) ( 2)

Reserves $22,000 Checkable

Securities 38,000 deposits $100,000

Loans 40,000

mcc26632_ch13_244-257.indd 256mcc26632_ch13_244-257.indd 256 8/31/06 4:31:22 PM8/31/06 4:31:22 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 13

Money Creation

257

much and in what direction has the money supply changed?

Explain.

7. Suppose the National Bank of Commerce has excess

reserves of $8000 and outstanding checkable deposits of

$150,000. If the reserve ratio is 20 percent, what is the size

of the bank’s actual reserves?

8.

KEY QUESTION Suppose that Continental Bank has the

simplified balance sheet shown on the previous page and that

the reserve ratio is 20 percent:

a. What is the maximum amount of new loans that this

bank can make? Show in column 1 how the bank’s bal-

ance sheet will appear after the bank has lent this addi-

tional amount.

b. By how much has the supply of money changed?

Explain.

c. How will the bank’s balance sheet appear after checks

drawn for the entire amount of the new loans have been

cleared against the bank? Show the new balance sheet in

column 2.

d. Answer questions a, b, and c on the assumption that the

reserve ratio is 15 percent.

9. The Third National Bank has reserves of $20,000 and

checkable deposits of $100,000. The reserve ratio is 20

percent. Households deposit $5000 in currency into the

bank that is added to reserves. What level of excess reserves

does the bank now have?

10. Suppose again that the Third National Bank has reserves of

$20,000 and checkable deposits of $100,000. The reserve

ratio is 20 percent. The bank now sells $5000 in securities

to the Federal Reserve Bank in its district, receiving a $5000

increase in reserves in return. What level of excess reserves

does the bank now have? Why does your answer differ (yes,

it does!) from the answer to question 9?

11. Suppose a bank discovers that its reserves will temporarily

fall slightly short of those legally required. How might it

remedy this situation through the Federal funds market?

Now assume the bank finds that its reserves will be substan-

tially and permanently deficient. What remedy is available

to this bank? (Hint: Recall your answer to question 4.)

12. Suppose that Bob withdraws $100 of cash from his checking

account at Security Bank and uses it to buy a camera from

Joe, who deposits the $100 in his checking account in

Serenity Bank. Assuming a reserve ratio of 10 percent and

no initial excess reserves, determine the extent to which (a)

Security Bank must reduce its loans and checkable deposits

because of the cash withdrawal, (b) Serenity Bank can safely

increase its loans and checkable deposits because of the cash

deposit, and (c) the entire banking system, including Seren-

ity, can increase loans and checkable deposits because of the

cash deposit. Have the cash withdrawal and deposit changed

the total money supply?

13.

KEY QUESTION Suppose the simplified consolidated balance

sheet shown below is for the entire commercial banking sys-

tem. All figures are in billions. The reserve ratio is 25 percent.

Web-Based Questions

net worth (assets less liabilities) of all commercial banks in

the United States increased, decreased, or remained

constant during the past year?

2.

RESERVE REQUIREMENTS—ANY CHANGES TO TAB LE

13.1? Go to the Fed’s Web site, www.federalreserve.gov/,

and select “Monetary Policy.” Then, in order, select Reserve

Requirements and find the link to “low-reserve amounts

and exemptions.” Does any part of Table 13.1 need updat-

ing? If so, prepare a new, updated table.

1. ASSETS AND LIABILITIES OF ALL COMMERCIAL BANKS

IN THE UNITED STATES The Federal Reserve, at www.

federalreserve.gov/releases/h8/Current/, provides an

aggregate balance sheet for commercial banks in the United

States. Check the current release, and look in the asset

column for “Loans and leases.” Rank the following compo-

nents of loans and leases in terms of size: commercial and

industrial, real estate, consumer, security, and other. Over

the past 12 months, which component has increased by the

largest percentage? By the largest absolute amount? Has the

Assets Liabilities and net worth

(1)

Reserves $ 52

Securities 48

Loans 100

(1)

Checkable

deposits $200

a. What amount of excess reserves does the commercial

banking system have? What is the maximum amount the

banking system might lend? Show in column 1 how the

consolidated balance sheet would look after this amount

has been lent. What is the monetary multiplier?

b. Answer the questions in part a assuming the reserve

ratio is 20 percent. Explain the resulting difference in

the lending ability of the commercial banking system.

14.

LAST WORD Explain how the bank panics of 1930 to 1933

produced a decline in the nation’s money supply. Why are

such panics highly unlikely today?

mcc26632_ch13_244-257.indd 257mcc26632_ch13_244-257.indd 257 8/31/06 4:31:22 PM8/31/06 4:31:22 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

Interest Rates and Monetary Policy

Some newspaper commentators have stated that the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board

(previously Alan Greenspan and now Ben Bernanke) is the second most powerful person in the United

States, after the U.S. president. That is undoubtedly an exaggeration because the chair has only a

single vote on the 7-person Federal Reserve Board and 12-person Federal Open Market Committee.

But there can be no doubt about the chair’s influence, the overall importance of the Federal Reserve,

and the monetary policy that it conducts. Such policy consists of deliberate changes in the money

supply to influence interest rates and thus the total level of spending in the economy. The goal is to

achieve and maintain price-level stability, full employment, and economic growth.

IN THIS CHAPTER YOU WILL LEARN:

• How the equilibrium interest rate is determined in

the market for money.

• The goals and tools of monetary policy.

• About the Federal funds rate and how the Fed

controls it.

• The mechanisms by which monetary policy affects

GDP and the price level.

• The effectiveness of monetary policy and its

shortcomings.

14

mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 258mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 258 9/1/06 3:46:30 PM9/1/06 3:46:30 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 14

Interest Rates and Monetary Policy

259

Interest Rates

The Fed’s primary influence is on the money supply and

interest rates. So we initially need to better understand the

market in which interest rates are established. Interest is

the price paid for the use of money. It is the price that bor-

rowers need to pay lenders for transferring purchasing

power to the future. It can be thought of as the amount of

money that must be paid for the use of $1 for 1 year. Al-

though there is a full cluster of U.S. interest rates that vary

by purpose, size, risk, maturity, and taxability, we will sim-

ply speak of “the interest rate” unless stated otherwise.

Let’s see how the interest rate is determined. Because

it is a “price,” we again turn to demand and supply analysis

for the answer.

The Demand for Money

Why does the public want to hold some of its wealth as

money? There are two main reasons: to make purchases

with it and to hold it as an asset.

Transactions Demand, D

t

People hold money

because it is convenient for purchasing goods and services.

Households usually are paid once a week, every 2 weeks,

or monthly, whereas their expenditures are less predict-

able and typically more frequent. So households must have

enough money on hand to buy groceries and pay mort-

gage and utility bills. Nor are business revenues and

expenditures simultaneous. Businesses need to have money

available to pay for labor, materials, power, and other in-

puts. The demand for money as a medium of exchange is

called transactions demand for money.

The level of nominal GDP is the main determinant of

the amount of money demanded for transactions. The

larger the total money value of all goods and services ex-

changed in the economy, the larger the amount of money

needed to negotiate those transactions. The transactions

demand for money varies directly with nominal GDP. We

specify nominal GDP because households and firms will

want more money for transactions if prices rise or if real

output increases. In both instances a larger dollar volume

will be needed to accomplish the desired transactions.

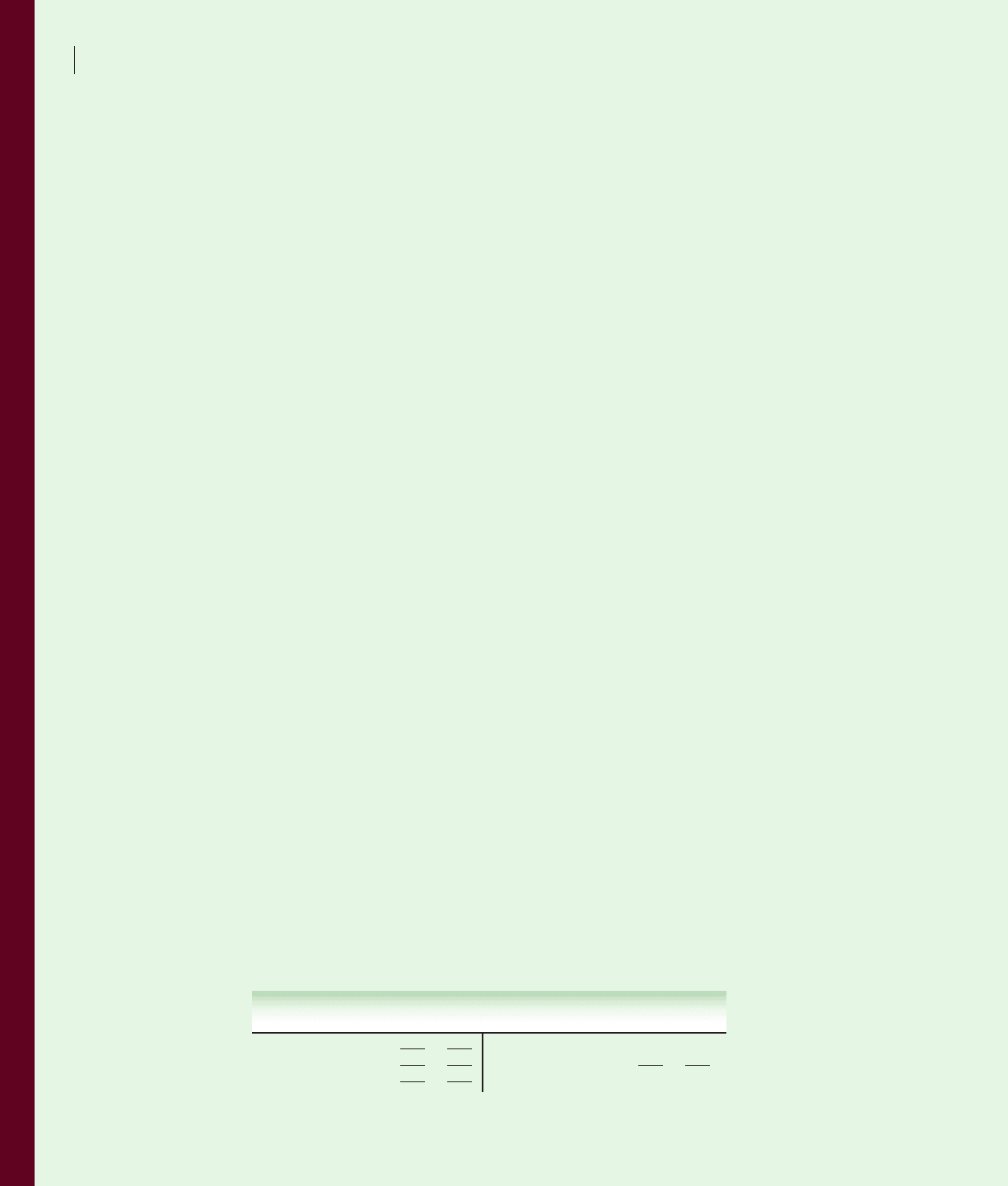

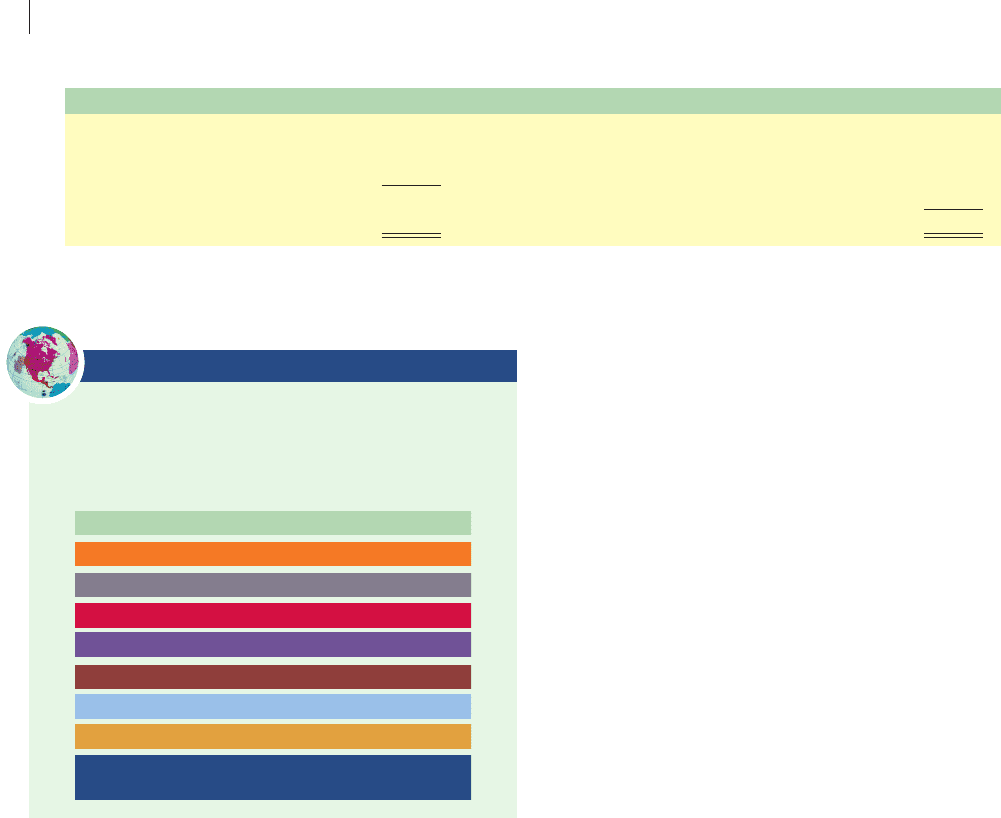

In Figure 14.1 a we graph the quantity of money de-

manded for transactions against the interest rate. For sim-

plicity, let’s assume that the amount demanded depends

exclusively on the level of nominal GDP and is indepen-

dent of the interest rate. (In reality, higher interest rates

are associated with slightly lower volumes of money de-

manded for transactions.) Our simplifying assumption

allows us to graph the transactions demand, D

t

, as a vertical

line. This demand curve is positioned at $100 billion, on

the assumption that each dollar held for transactions pur-

poses is spent on an average of three times per year and

that nominal GDP is $300 billion. Thus the public needs

$100 billion ( $300 billion兾3) to purchase that GDP.

Asset Demand, D

a

The second reason for holding

money derives from money’s function as a store of value.

People may hold their financial assets in many forms, in-

cluding corporate stocks, corporate or government bonds,

or money. To the extent they want to hold money as an

asset, there is an asset demand for money.

People like to hold some of their financial assets as

money (apart from using it to buy goods and services)

because money is the most liquid of all financial assets; it is

immediately usable for purchasing other assets when oppor-

tunities arise. Money is also an attractive asset to hold when

the prices of other assets such as bonds are expected to de-

cline. For example, when the price of a bond falls, the bond-

holder who sells the bond prior to the payback date of the

full principal will suffer a loss (called a capital loss ). That loss

will partially or fully offset the interest received on the bond.

There is no such risk of capital loss in holding money.

The disadvantage of holding money as an asset is that

it earns no or very little interest. Checkable deposits pay

either no interest or lower interest rates than bonds. Idle

currency, of course, earns no interest at all.

Knowing these advantages and disadvantages, the

public must decide how much of its financial assets to hold

as money, rather than other assets such as bonds. The an-

swer depends primarily on the rate of interest. A house-

hold or a business incurs an opportunity cost when it holds

money; in both cases, interest income is forgone or sacri-

ficed. If a bond pays 6 percent interest, for example, hold-

ing $100 as cash or in a noninterest checkable account

costs $6 per year of forgone income.

The amount of money demanded as an asset therefore

varies inversely with the rate of interest (the opportunity

cost of holding money as an asset). When the interest rate

rises, being liquid and avoiding capital losses becomes more

costly. The public reacts by reducing its

holdings of money as an asset. When the in-

terest rate falls, the cost of being liquid and

avoiding capital losses also declines. The

public therefore increases the amount of

financial assets that it wants to hold as

money. This inverse relationship just de-

scribed is shown by D

a

in Figure 14.1 b.

Total Money Demand, D

m

As shown in

Figure 14.1 , we find the total demand for money D

m

, by

horizontally adding the asset demand to the transactions

O 14.1

Liquidity

preference

mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 259mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 259 9/1/06 3:46:32 PM9/1/06 3:46:32 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

260

key

graph

Rate of interest, i

(percent)

Rate of interest, i

(percent)

Rate of interest, i

(percent)

Amount of money demanded

(billions of dollars)

Amount of money demanded

(billions of dollars)

Amount of money demanded

and supplied

(billions of dollars)

(a)

Transactions demand

for money, D

t

(b)

Asset demand

for money, D

a

(c)

Total demand for money,

D

m

= D

t

+ D

a

, and supply

of mone

y

10

7.5

5

2.5

50 150

100 200

0

10

7.5

5

2.5

50 150

100 200

0

10

7.5

2.5

50 150

100 200

0 250

300

i

e

D

t

D

a

D

m

S

m

FIGURE 14.1 The demand for money, the supply of money, and the equilibrium interest rate. The total demand for

money D

m

is determined by horizontally adding the asset demand for money D

a

to the transactions demand D

t

. The transactions demand is vertical

because it is assumed to depend on nominal GDP rather than on the interest rate. The asset demand varies inversely with the interest rate because of

the opportunity cost involved in holding currency and checkable deposits that pay no interest or very low interest. Combining the money supply (stock)

S

m

with the total money demand D

m

portrays the market for money and determines the equilibrium interest rate i

e

.

QUICK QUIZ 14.1

1. In this graph, at the interest rate i

e

(5 percent):

a. the amount of money demanded as an asset is $50 billion.

b. the amount of money demanded for transactions is

$200 billion.

c. bond prices will decline.

d. $100 billion is demanded for transactions, $100 billion is

demanded as an asset, and the money supply is $200 billion.

2. In this graph, at an interest rate of 10 percent:

a. no money will be demanded as an asset.

b. total money demanded will be $200 billion.

c. the Federal Reserve will supply $100 billion of money.

d. there will be a $100 billion shortage of money.

3. Curve D

a

slopes downward because:

a. lower interest rates increase the opportunity cost of holding

money.

b. lower interest rates reduce the opportunity cost of holding

money.

c. the asset demand for money varies directly (positively) with

the interest rate.

d. the transactions-demand-for-money curve is perfectly vertical.

4. Suppose the supply of money declines to $100 billion. The

equilibrium interest rate would:

a. fall, the amount of money demanded for transactions would

rise, and the amount of money demanded as an asset would

decline.

b. rise, and the amounts of money demanded both for

transactions and as an asset would fall.

c. fall, and the amounts of money demanded both for

transactions and as an asset would increase.

d. rise, the amount of money demanded for transactions would

be unchanged, and the amount of money demanded as an

asset would decline.

Answers: 1. d; 2. a; 3. b; 4. d

demand. The resulting downward-sloping line in Figure 14.1 c

represents the total amount of money the public wants to

hold, both for transactions and as an asset, at each possible

interest rate.

Recall that the transactions demand for money depends

on the nominal GDP. A change in the nominal GDP—

working through the transactions demand for money—will

shift the total money demand curve. Specifically, an increase

in nominal GDP means that the public

wants to hold a larger amount of money for

transactions, and that extra demand will

shift the total money demand curve to the

right. In contrast, a decline in the nominal

GDP will shift the total money demand

curve to the left. As an example, suppose

nominal GDP increases from $300 billion

W 14.1

Demand for

money

mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 260mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 260 9/1/06 3:46:33 PM9/1/06 3:46:33 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 14

Interest Rates and Monetary Policy

261

to $450 billion and the average dollar held for transactions

is still spent three times per year. Then the transactions

demand curve will shift from $100 billion ( $300 billion兾3)

to $150 billion ( $450 billion兾3). The total money de-

mand curve will then lie $50 billion farther to the right at

each possible inte rest rate.

The Equilibrium Interest Rate

We can combine the demand for money with the supply of

money to determine the equilibrium rate of interest. In

Figure 14.1 c the vertical line, S

m

, represents the money

supply. It is a vertical line because the monetary authorities

and financial institutions have provided the economy with

some particular stock of money. Here it is $200 billion.

Just as in a product market or a resource market, the

intersection of demand and supply determines the equilib-

rium price in the market for money. Here, the equilibrium

“price” is the interest rate ( i

e

)—the price that is paid for

the use of money over some time period.

Changes in the demand for money, the

supply of money, or both can change

the equilibrium interest rate. For reasons

that will soon become apparent, we are most

interested in changes in the supply of

money. The important generalization is

this: An increase in the supply of money will

lower the equilibrium interest rate; a de-

crease in the supply of money will raise the equilibrium in-

terest rate. (Key Questions 1 and 2)

Interest Rates and Bond Prices

Interest rates and bond prices are closely related. When

the interest rate increases, bond prices fall; when the

interest rate falls, bond prices rise. Why so? First under-

stand that bonds are bought and sold in financial markets,

and that the price of bonds is determined by bond demand

and bond supply.

Suppose that a bond with no expiration date pays a

fixed $50 annual interest and is selling for its face value of

$1000. The interest yield on this bond is 5 percent:

$50

______

$1000

5% interest yield

Now suppose the interest rate in the economy rises to

7

1

_

2

percent from 5 percent. Newly issued bonds will pay

$75 per $1000 lent. Older bonds paying only $50 will

not be salable at their $1000 face value. To compete with

the 7

1

_

2

percent bond, the price of this bond will need to

fall to $667 to remain competitive. The $50 fixed annual

G 14.1

Equilibrium

interest rate

interest payment will then yield 7

1

_

2

percent to whoever

buys the bond:

$50

_____

$667

7

1

_

2

%

Next suppose that the interest rate falls to 2

1

_

2

percent from

the original 5 percent. Newly issued bonds will pay $25 on

$1000 loaned. A bond paying $50 will be highly attractive.

Bond buyers will bid up its price to $2000, at which the

yield will equal 2

1

_

2

percent:

$50

______

$2000

2

1

_

2

%

The point is that bond prices fall when the

interest rate rises and rise when the inter-

est rate falls. There is an inverse relation-

ship between the interest rate and bond

prices. (Key Question 3)

QUICK REVIEW 14.1

• People demand money for transaction and asset purposes.

• The total demand for money is the sum of the transactions

and asset demands; it is graphed as an inverse relationship

(downward-sloping line) between the interest rate and the

quantity of money demanded.

• The equilibrium interest rate is determined by money

demand and supply; it occurs when people are willing to hold

the exact amount of money being supplied by the monetary

authorities.

• Interest rates and bond prices are inversely related.

The Consolidated Balance

Sheet of the Federal

Reserve Banks

With this basic understanding of interest rates we can turn

to monetary policy, which relies on changes in interest

rates to be effective. The 12 Federal Reserve Banks to-

gether constitute the U.S. “central bank,” nicknamed the

“Fed.” (Global Perspective 14.1 also lists some of the

other central banks in the world, along with their

nicknames.)

The Fed’s balance sheet helps us consider how the

Fed conducts monetary policy. Table 14.1 consolidates

the pertinent assets and liabilities of the 12 Federal Re-

serve Banks as of March 29, 2006. You will see that some

of the Fed’s assets and liabilities differ from those found

on the balance sheet of a commercial bank.

W 14.2

Bond prices and

interest rates

mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 261mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 261 9/1/06 3:46:33 PM9/1/06 3:46:33 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART FOUR

Money, Banking, and Monetary Policy

262

Assets

The two main assets of the Federal Reserve Banks are se-

curities and loans to commercial banks. (Again, we will

simplify by referring only to commercial banks, even though

the analysis also applies to thrifts —savings and loans, mu-

tual savings banks, and credit unions.)

Securities The securities shown in Table 14.1 are gov-

ernment bonds that have been purchased by the Federal

Reserve Banks. They consist largely of Treasury bills

(short-term securities), Treasury notes (mid-term securi-

ties), and Treasury bonds (long-term securities) issued by

the U.S. government to finance past budget deficits. These

securities are part of the public debt—the money borrowed

by the Federal government. The Federal Reserve Banks

bought these securities from commercial banks and the

public through open-market operations. Although they are

an important source of interest income to the Federal

Reserve Banks, they are mainly bought and sold to influ-

ence the size of commercial bank reserves and, therefore,

the ability of those banks to create money by lending.

Loans to Commercial Banks For reasons that

will soon become clear, commercial banks occasionally

borrow from Federal Reserve Banks. The IOUs that com-

mercial banks give these “bankers’ banks” in return for

loans are listed on the Federal Reserve balance sheet as

“Loans to commercial banks.” They are assets to the Fed

because they are claims against the commercial banks. To

commercial banks, of course, these loans are liabilities in

that they must be repaid. Through borrowing in this way,

commercial banks can increase their reserves.

Liabilities

On the liability side of the Fed’s consolidated balance

sheet, we find three items: reserves, Treasury deposits, and

Federal Reserve Notes.

Reserves of Commercial Banks The Fed

requires that the commercial banks hold reserves against

their checkable deposits. When held in the Federal Re-

serve Banks, these reserves are listed as a liability on the

Fed’s balance sheet. They are assets on the books of the

commercial banks, which still own them even though they

are deposited at the Federal Reserve Banks.

Treasury Deposits The U.S. Treasury keeps de-

posits in the Federal Reserve Banks and draws checks on

them to pay its obligations. To the Treasury these deposits

are assets; to the Federal Reserve Banks they are liabilities.

The Treasury creates and replenishes these deposits by de-

positing tax receipts and money borrowed from the public

or from the commercial banks through the sale of bonds.

Federal Reserve Notes Outstanding As we

have seen, the supply of paper money in the United States

consists of Federal Reserve Notes issued by the Federal

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE 14.1

Central Banks, Selected Nations

The monetary policies of the world’s major central banks are

often in the international news. Here are some of their official

names, along with a few of their popular nicknames.

Australia: Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA)

Canada: Bank of Canada

Euro Zone: European Central Bank (ECB)

Japan: The Bank of Japan (“BOJ”)

Sweden: Sveriges Riksbank

United Kingdom: Bank of England

United States: Federal Reserve System

(the “Fed”) (12 regional Federal Reserve Banks)

Russia: Central Bank of Russia

Mexico: Banco de Mexico (Mex Bank)

Source: Federal Reserve Statistical Release, H.4.1, March 29, 2006, www.federalreserve.gov/.

TABLE 14.1 Consolidated Balance Sheet of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks, March 29, 2006 (in Millions)

Assets Liabilities and Net Worth

Securities $758,551 Reserves of commercial banks $ 14,923

Loans to commercial banks 19,250 Treasury deposits 4,663

All other assets 59,967 Federal Reserve Notes (outstanding) 754,567

All other liabilities and net worth 63,615

Total $837,768 Total $837,768

mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 262mcc26632_ch14_258-283.indd 262 9/1/06 3:46:34 PM9/1/06 3:46:34 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES