McConnell С., Campbell R. Macroeconomics: principles, problems, and policies, 17th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

CHAPTER 11

Fiscal Policy, Deficits, and Debt

223

Last

Word

The Leading Indicators

One of Several Tools Policymakers Use to Forecast

the Future Direction of Real GDP Is a Monthly

Index of 10 Variables That in the Past Have Provided

Advance Notice of Changes in GDP.

The Conference Board’s index of leading indicators has historically

reached a peak or a trough in advance of corresponding turns in

the business cycle. * Thus changes in this composite index of 10

economic variables provide a clue to the future direction of the

economy. Such advance warning helps policymakers formulate

appropriate macroeconomic policy.

Here is how each of the 10 compo-

nents of the index would change if it

were predicting a decline in real GDP.

The opposite changes would forecast a

rise in real GDP.

1. Average workweek Decreases in the

length of the average workweek

of production workers in manufac-

turing foretell declines in future

manufacturing output and possible

declines in real GDP.

2. Initial claims for unemployment

insurance Higher first-time claims

for unemployment insurance are

associated with falling employment

and subsequently sagging real GDP.

3. New orders for consumer goods Decreases in the number of

orders received by manufacturers for consumer goods

portend reduced future production—a decline in real GDP.

4. Vendor performance Somewhat ironically, better on-time

delivery by sellers of inputs indicates slackening business

demand for final output and potentially falling real GDP.

5. New orders for capital goods A drop in orders for capital

equipment and other investment goods implies reduced

future spending by businesses and thus reduced aggregate

demand and lower real GDP.

6. Building permits for houses Decreases in the number of build-

ing permits issued for new homes imply future declines in in-

vestment and therefore the possibility that real GDP will fall.

7. Stock prices Declines in stock prices often are reflections of ex-

pected declines in corporate sales and profits. Also, lower

stock prices diminish consumer wealth, leading to possible

cutbacks in consumer spending. Lower stock prices also make

it less attractive for firms to issue new shares of stock as a way

of raising funds for investment. Thus, declines in stock prices

can mean declines in future aggregate demand and real GDP.

8. Money supply Decreases in the nation’s money supply are as-

sociated with falling real GDP.

9. Interest-rate spread Increases in short-term nominal interest

rates typically reflect monetary policies designed to slow the

economy. Such policies have much less effect on long-term

interest rates, which usually are higher

than short-term rates. So a smaller differ-

ence between short-term interest rates

and long-term interest rates suggests

restrictive monetary policies and poten-

tially a future decline in GDP.

10. Consumer expectations Less favorable

consumer attitudes about future

economic conditions, measured by

an index of consumer expectations,

foreshadow lower consumption

spending and potential future

declines in GDP.

None of these factors alone consis-

tently predicts the future course of the

economy. It is not unusual in any

month, for example, for one or two of

the indicators to be decreasing while the

other indicators are increasing. Rather, changes in the compos-

ite of the 10 components are what in the past have provided

advance notice of a change in the direction of GDP. The rule of

thumb is that three successive monthly declines or increases in

the index indicate the economy will soon turn in that same

direction.

Although the composite index has correctly signaled business

fluctuations on numerous occasions, it has not been infallible. At

times the index has provided false warnings of recessions that

never happened. In other instances, recessions have so closely

followed the downturn in the index that policymakers have not

had sufficient time to make use of the “early” warning. Moreover,

changing structural features of the economy have, on occasion,

rendered the existing index obsolete and necessitated its revision.

Given these caveats, the index of leading indicators can

best be thought of as a useful but not totally reliable signaling

device that authorities must employ with considerable caution

in formulating macroeconomic policy.

*The Conference Board is a private, nonprofit research and business

membership group, with more than 2700 corporate and other members

in 60 nations. See www.conferenceboard.org .

223

mcc26632_ch11_208-226.indd 223mcc26632_ch11_208-226.indd 223 8/21/06 4:35:15 PM8/21/06 4:35:15 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART THREE

Macroeconomic Models and Fiscal Policy

224

Summary

1. Fiscal policy consists of deliberate changes in government

spending, taxes, or some combination of both to promote

full employment, price-level stability, and economic growth.

Fiscal policy requires increases in government spending,

decreases in taxes, or both—a budget deficit—to increase

aggregate demand and push an economy from a recession.

Decreases in government spending, increases in taxes, or

both—a budget surplus—are appropriate fiscal policy for

dealing with demand-pull inflation.

2. Built-in stability arises from net tax revenues, which vary

directly with the level of GDP. During recession, the Fed-

eral budget automatically moves toward a stabilizing deficit;

during expansion, the budget automatically moves toward

an anti-inflationary surplus. Built-in stability lessens, but

does not fully correct, undesired changes in the real GDP.

3. The standardized budget measures the Federal budget defi-

cit or surplus that would occur if the economy operated at

full employment throughout the year. Cyclical deficits or

surpluses are those that result from changes in GDP. Changes

in the standardized deficit or surplus provide meaningful

information as to whether the government’s fiscal policy is

expansionary, neutral, or contractionary. Changes in the ac-

tual budget deficit or surplus do not, since such deficits or

surpluses can include cyclical deficits or surpluses.

4. Certain problems complicate the enactment and implementa-

tion of fiscal policy. They include (a) timing problems

associated with recognition, administrative, and operational

lags; (b) the potential for misuse of fiscal policy for political

rather than economic purposes; (c) the fact that state and

local finances tend to be pro-cyclical; (d) potential ineffective-

ness if households expect future policy reversals; and (e) the

possibility of fiscal policy crowding out private investment.

5. Most economists believe that fiscal policy can help move the

economy in a desired direction but cannot reliably be used

to fine-tune the economy to a position of price stability and

full employment. Nevertheless, fiscal policy is a valuable

backup tool for aiding monetary policy in fighting signifi-

cant recession or inflation.

6. The large Federal budget deficits of the 1980s and early

1990s prompted Congress in 1993 to increase tax rates and

limit government spending. As a result of these policies,

along with a very rapid and prolonged economic expansion,

the deficits dwindled to $22 billion in 1997. Large budget

surpluses occurred in 1999, 2000, and 2001. In 2001 the

Congressional Budget Office projected that $5 trillion of

annual budget surpluses would accumulate between 2000

and 2010.

7. In 2001 the Bush administration and Congress chose to re-

duce marginal tax rates and phase out the Federal estate tax.

A recession occurred in 2001, the stock market crashed, and

Federal spending for the war on terrorism rocketed. The

Federal budget swung from a surplus of $127 billion in 2001

to a deficit of $158 billion in 2002. In 2003 the Bush

administration and Congress accelerated the tax reductions

scheduled under the 2001 tax law and cut tax rates on capital

gains and dividends. The purposes were to stimulate a

sluggish economy. In 2005 the budget deficit was $318 bil-

lion and deficits are projected to continue through 2011

before surpluses again reemerge.

8. The public debt is the total accumulation of the govern-

ment’s deficits (minus surpluses) over time and consists of

Treasury bills, Treasury notes, Treasury bonds, and U.S.

savings bonds. In 2005 the U.S. public debt was nearly

$8 trillion, or $26,834 per person. The public (which here

includes banks and state and local governments) holds

49 percent of that Federal debt; the Federal Reserve and

Federal agencies hold the other 51 percent. Foreigners hold

25 percent of the Federal debt. Interest payments as a per-

centage of GDP were about 1.5 percent in 2005. This is

down from 3.2 percent in 1990.

9. The concern that a large public debt may bankrupt the

government is a false worry because (a) the debt needs only

to be refinanced rather than refunded and (b) the Federal

government has the power to increase taxes to make interest

payments on the debt.

10. In general, the public debt is not a vehicle for shifting eco-

nomic burdens to future generations. Americans inherit not

only most of the public debt (a liability) but also most of the

U.S. securities (an asset) that finance the debt.

11. More substantive problems associated with public debt

include the following: (a) Payment of interest on the debt

may increase income inequality. (b) Interest payments on

the debt require higher taxes, which may impair incentives.

(c) Paying interest or principal on the portion of the debt

held by foreigners means a transfer of real output abroad.

(d) Government borrowing to refinance or pay interest on

the debt may increase interest rates and crowd out private

investment spending, leaving future generations with a

smaller stock of capital than they would have otherwise.

12. The increase in investment in public capital that may result

from debt financing may partly or wholly offset the crowd-

ing-out effect of the public debt on private investment. Also,

the added public investment may stimulate private invest-

ment, where the two are complements.

mcc26632_ch11_208-226.indd 224mcc26632_ch11_208-226.indd 224 8/21/06 4:35:16 PM8/21/06 4:35:16 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 11

Fiscal Policy, Deficits, and Debt

225

Terms and Concepts

fiscal policy

Council of Economic Advisers (CEA)

expansionary fiscal policy

budget deficit

contractionary fiscal policy

budget surplus

built-in stabilizer

progressive tax system

proportional tax system

regressive tax system

standardized budget

cyclical deficit

political business cycle

crowding-out effect

public debt

U.S. securities

external public debt

public investments

Study Questions

1. What is the role of the Council of Economic Advisers

(CEA) as it relates to fiscal policy? Class assignment: Deter-

mine the names and educational backgrounds of the present

members of the CEA.

2.

KEY QUESTION Assume that a hypothetical economy with

an MPC of .8 is experiencing severe recession. By how much

would government spending have to increase to shift the

aggregate demand curve rightward by $25 billion? How

large a tax cut would be needed to achieve the same increase

in aggregate demand? Why the difference? Determine one

possible combination of government spending increases and

tax decreases that would accomplish the same goal.

3.

KEY QUESTION What are government’s fiscal policy op-

tions for ending severe demand-pull inflation? Use the ag-

gregate demand–aggregate supply model to show the impact

of these policies on the price level. Which of these fiscal op-

tions do you think might be favored by a person who wants

to preserve the size of government? A person who thinks

the public sector is too large?

4. (For students who were assigned Chapter 9) Use the aggre-

gate expenditures model to show how government fiscal

policy could eliminate either a recessionary expenditure gap

or an inflationary expenditure gap (Figure 9.7). Explain how

equal-size increases in G and T could eliminate a recession-

ary gap and how equal-size decreases in G and T could elim-

inate an inflationary gap.

5. Explain how built-in (or automatic) stabilizers work. What

are the differences between proportional, progressive, and

regressive tax systems as they relate to an economy’s built-in

stability?

6.

KEY QUESTION Define the standardized budget, explain its

significance, and state why it may differ from the actual

budget. Suppose the full-employment, noninflationary level

of real output is GDP

3

(not GDP

2

) in the economy depicted

in Figure 11.3 . If the economy is operating at GDP

2

, in-

stead of GDP

3

, what is the status of its standardized budget?

The status of its current fiscal policy? What change in fiscal

policy would you recommend? How would you accomplish

that in terms of the G and T lines in the figure?

7. Some politicians have suggested that the United States en-

act a constitutional amendment requiring that the Federal

government balance its budget annually. Explain why such

an amendment, if strictly enforced, would force the govern-

ment to enact a contractionary fiscal policy whenever the

economy experienced a severe recession.

8.

KEY QUESTION Briefly state and evaluate the problem of

time lags in enacting and applying fiscal policy. Explain the

idea of a political business cycle. How might expectations of

a near-term policy reversal weaken fiscal policy based on

changes in tax rates? What is the crowding-out effect, and

why might it be relevant to fiscal policy? In view of your

answers, explain the following statement: “Although fiscal

policy clearly is useful in combating the extremes of severe

recession and demand-pull inflation, it is impossible to

use fiscal policy to fine-tune the economy to the full-

employment, noninflationary level of real GDP and keep

the economy there indefinitely.”

9.

ADVANCED ANALYSIS (For students who were assigned

Chapter 9) Assume that, without taxes, the consumption

schedule for an economy is as shown below:

GDP, Consumption,

Billions Billions

$100 $120

200 200

300 280

400 360

500 440

600 520

700 600

a. Graph this consumption schedule, and determine the

size of the MPC.

b. Assume that a lump-sum (regressive) tax of $10 billion

is imposed at all levels of GDP. Calculate the tax rate at

each level of GDP. Graph the resulting consumption

schedule, and compare the MPC and the multiplier

with those of the pretax consumption schedule.

mcc26632_ch11_208-226.indd 225mcc26632_ch11_208-226.indd 225 8/21/06 4:35:16 PM8/21/06 4:35:16 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART THREE

Macroeconomic Models and Fiscal Policy

226

c. Now suppose a proportional tax with a 10 percent tax

rate is imposed instead of the regressive tax. Calculate

and graph the new consumption schedule, and note the

MPC and the multiplier.

d. Finally, impose a progressive tax such that the tax rate

is 0 percent when GDP is $100, 5 percent at $200,

10 percent at $300, 15 percent at $400, and so forth.

Determine and graph the new consumption schedule,

noting the effect of this tax system on the MPC and the

multiplier.

e. Explain why proportional and progressive taxes contrib-

ute to greater economic stability, while a regressive tax

does not. Demonstrate, using a graph similar to

Figure 11.3 .

10.

KEY QUESTION How do economists distinguish between

the absolute and relative sizes of the public debt? Why is the

distinction important? Distinguish between refinancing the

debt and retiring the debt. How does an internally held

public debt differ from an externally held public debt? Con-

trast the effects of retiring an internally held debt and retir-

ing an externally held debt.

11. True or false? If false, explain why.

a. The total public debt is more relevant to an economy

than the public debt as percentage of GDP.

b. An internally held public debt is like a debt of the left

hand owed to the right hand.

c. The Federal Reserve and Federal government agencies

hold more than three-fourths of the public debt.

d. The portion of the U.S. debt held by the public (and

not by government entities) was larger as a percentage

of GDP in 2005 than it was in 1995.

e. In recent years, Social Security payments to retirees

have exceeded Social Security tax revenues from

workers and their employers.

12. Why might economists be quite concerned if the annual in-

terest payments on the debt sharply increased as a percent-

age of GDP?

13.

KEY QUESTION Trace the cause-and-effect chain through

which financing and refinancing of the public debt might

affect real interest rates, private investment, the stock of

capital, and economic growth. How might investment in

public capital and complementarities between public capital

and private capital alter the outcome of the cause-effect

chain?

14. What would happen to the stated sizes of Federal budget

deficits or surpluses if the current annual additions or sub-

tractions from the Social Security trust fund were

excluded?

15. What is the index of leading economic indicators, and how

does it relate to discretionary fiscal policy?

Web-Based Questions

1. LEADING ECONOMIC INDICATORS—HOW GOES THE

ECONOMY? The Conference Board, at www.conference-

board.org/ , tracks the leading economic indicators. Check

the summary of the index of leading indicators and its indi-

vidual components for the latest month. Is the index up or

down? Which specific components are up, and which are

down? What has been the trend of the composite index over

the past 3 months?

2.

TEXT TABLE 11.1 , COLUMN 3—WHAT ARE THE LAT-

EST NUMBERS? Go to the Congressional Budget Office

Web site, www.cbo.gov , and select Historical Budget Data.

Find the historical data for the actual budget deficit or sur-

plus (total). Update column 2 of text Table 11.1 . Next, find

the historical data for the standardized (full-employment)

budget deficit or surplus as a percentage of potential GDP.

Update column 3 of Table 11.1 . Is fiscal policy more expan-

sionary or less expansionary than it was in 2005?

mcc26632_ch11_208-226.indd 226mcc26632_ch11_208-226.indd 226 8/21/06 4:35:16 PM8/21/06 4:35:16 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART FOUR

Money, Banking, and

Monetary Policy

12 MONEY AND BANKING

13 MONEY CREATION

14 INTEREST RATES AND MONETARY

POLICY

14W FINANCIAL ECONOMICS

mcc26632_ch12_227-243.indd 227mcc26632_ch12_227-243.indd 227 8/21/06 4:47:20 PM8/21/06 4:47:20 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

Money and Banking

Money is a fascinating aspect of the economy:

Money bewitches people. They fret for it, and they sweat for it. They devise most ingenious ways to

get it, and most ingenuous ways to get rid of it. Money is the only commodity that is good for nothing

but to be gotten rid of. It will not feed you, clothe you, shelter you, or amuse you unless you spend it

or invest it. It imparts value only in parting. People will do almost anything for money, and money will

do almost anything for people. Money is a captivating, circulating, masquerading puzzle.

1

In this chapter and the two chapters that follow we want to unmask the critical role of money and

the monetary system in the economy. When the monetary system is working properly, it provides

1

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, “Creeping Inflation,” Business Review, August 1957, p. 3.

IN THIS CHAPTER YOU WILL LEARN:

• About the functions of money and the components

of the U.S. money supply.

• What “backs” the money supply, making us willing

to accept it as payment.

• The makeup of the Federal Reserve and the U.S.

banking system.

• The functions and responsibilities of the Federal

Reserve.

12

mcc26632_ch12_227-243.indd 228mcc26632_ch12_227-243.indd 228 8/21/06 4:47:22 PM8/21/06 4:47:22 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 12

Money and Banking

229

The Functions of Money

Just what is money? There is an old saying that “money is

what money does .” In a general sense, anything that performs

the functions of money is money. Here are those functions:

• Medium of exchange First and foremost, money is a

medium of exchange that is usable for buying and

selling goods and services. A bakery worker does not

want to be paid 200 bagels per week. Nor does the

bakery owner want to receive, say, halibut in exchange

for bagels. Money, however, is readily acceptable as

payment. As we saw in Chapter 2, money is a social

invention with which resource suppliers and producers

can be paid and that can be used to buy any of the full

range of items available in the marketplace. As a

medium of exchange, money allows society to escape

the complications of barter. And because it provides a

convenient way of exchanging goods, money enables

society to gain the advantages of geographic and

human specialization.

• Unit of account Money is also a unit of account .

Society uses monetary units—dollars, in the United

States—as a yardstick for measuring the relative worth

of a wide variety of goods, services, and resources. Just

as we measure distance in miles or kilometers, we

gauge the value of goods in dollars.

With money as an acceptable unit of account,

the price of each item need be stated only in terms of

the monetary unit. We need not state the price of

cows in terms of corn, crayons, and cranberries.

Money aids rational decision making by enabling

buyers and sellers to easily compare the prices of

various goods, services, and resources. It also permits

us to define debt obligations, determine taxes owed,

and calculate the nation’s GDP.

• Store of value Money also serves as a store of value

that enables people to transfer purchasing power

from the present to the future. People normally do not

spend all their incomes on the day they receive them.

In order to buy things later, they store some of their

wealth as money. The money you place in a safe or a

checking account will still be available to you a few

weeks or months from now. Money is often the pre-

ferred store of value for short periods because it is the

most liquid (spendable) of all assets. People can obtain

their money nearly instantly and can immediately use

it to buy goods or take advantage of financial invest-

ment opportunities. When inflation is nonexistent or

mild, holding money is a relatively risk-free way to

store your wealth for later use.

The Components of the

Money Supply

Money is a “stock” of some item or group of items (unlike

income, for example, which is a “flow”). Societies have

used many items as money, including whales’ teeth, circu-

lar stones, elephant-tail bristles, gold coins, furs, and

pieces of paper. Anything that is widely accepted as a me-

dium of exchange can serve as money. In the United States,

certain debts of government and of financial institutions

are used as money, as you will see.

Money Definition M1

The narrowest definition of the U.S. money supply is

called M1 . It consists of:

• Currency (coins and paper money) in the hands of

the public.

• All checkable deposits (all deposits in commercial

banks and “thrift” or savings institutions on which

checks of any size can be drawn).

2

Government and government agencies supply coins and

paper money. Commercial banks (“banks”) and savings

institutions (“thrifts”) provide checkable deposits. Figure

12.1 a shows the amounts of each category of money in the

M 1 money supply.

Currency: Coins ⫹ Paper Money From copper

pennies to gold-colored dollars, coins are the “small

change” of our money supply. All coins in circulation in

the United States are token money . This means that the

2

In the ensuing discussion, we do not discuss several of the quantitatively

less significant components of the definitions of money in order to avoid

a maze of details. For example, traveler’s checks are included in the M1

money supply. The statistical appendix of any recent Federal Reserve Bulletin

provides more comprehensive definitions.

the lifeblood of the circular flows of income and expenditure. A well-operating monetary system

helps the economy achieve both full employment and the efficient use of resources. A malfunctioning

monetary system creates severe fluctuations in the economy’s levels of output, employment, and

prices and distorts the allocation of resources.

229

mcc26632_ch12_227-243.indd 229mcc26632_ch12_227-243.indd 229 8/21/06 4:47:24 PM8/21/06 4:47:24 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART FOUR

Money, Banking, and Monetary Policy

230

intrinsic value, or the value of the metal contained in the

coin itself, is less than the face value of the coin. This is to

prevent people from melting down the coins for sale as a

“commodity,” in this case, the metal. If 50-cent pieces

each contained 75 cents’ worth of silver metal, it would be

profitable to melt them and sell the metal. The 50-cent

pieces would disappear from circulation.

Most of the nation’s currency is paper money. This

“folding currency” consists of Federal Reserve Notes ,

issued by the Federal Reserve System (the U.S. central

bank) with the authorization of Congress. Every bill car-

ries the phrase “Federal Reserve Note” on its face.

Figure 12.1 a shows that currency (coins and paper

money) constitutes 54 percent of the M 1 money supply in

the United States.

Checkable Deposits The safety and convenience

of checks has made checkable deposits a large component

of the M 1 money supply. You would not think of stuffing

$4896 in bills in an envelope and dropping it in a mailbox to

pay a debt. But writing and mailing a check for a large sum is

commonplace. The person cashing a check must endorse it

(sign it on the reverse side); the writer of the check subse-

quently receives a record of the cashed check as a receipt at-

testing to the fulfillment of the obligation. Similarly, because

the writing of a check requires endorsement, the theft or loss

of your checkbook is not nearly as calamitous as losing an

identical amount of currency. Finally, it is more convenient

to write a check than to transport and count out a large sum

of currency. For all these reasons, checkable deposits (check-

book money) are a large component of the stock of money in

the United States. About 46 percent of M 1 is in the form of

checkable deposits, on which checks can be drawn.

It might seem strange that checking account balances

are regarded as part of the money supply. But the reason is

clear: Checks are nothing more than a way to transfer the

ownership of deposits in banks and other financial institu-

tions and are generally acceptable as a medium of ex-

change. Although checks are less generally accepted than

currency for small purchases, for major purchases most

sellers willingly accept checks as payment. Moreover, peo-

ple can convert checkable deposits into paper money and

coins on demand; checks drawn on those deposits are thus

the equivalent of currency.

To summarize:

Money, M 1 ⫽ currency ⫹ checkable deposits

Institutions That Offer Checkable Deposits

In the United States, a variety of financial institutions allow

customers to write checks in any amount on the funds they

have deposited. Commercial banks are the primary depos-

itory institutions. They accept the deposits of households

and businesses, keep the money safe until it is demanded via

checks, and in the meantime use it to make available a wide

variety of loans. Commercial bank loans provide short-term

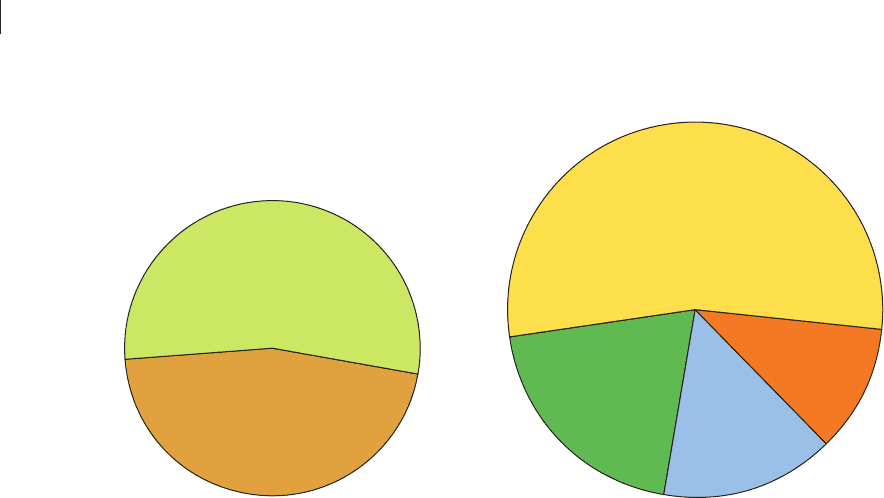

FIGURE 12.1 Components of money supply M1 and money supply M2, in the United States. (a) M1

is a narrow definition of the money supply that includes currency (in circulation) and checkable deposits. (b) M2 is a broader definition

that includes M1 along with several other relatively liquid account balances.

Currency

54%

Checkable

deposits*

46%

Money supply, M1

$1375 billion

Money supply, M2

$6758 billion

Savings deposits, including

money market deposit accounts

54%

M1

20%

Small

time

deposits*

15%

Money market

mutual funds held

by individuals

11%

(a) (b)

*These categories include other, quantitatively smaller components such as traveler’s checks.

Source: Federal Reserve System, www.federalreserve.gov. Data are for February 2006.

mcc26632_ch12_227-243.indd 230mcc26632_ch12_227-243.indd 230 8/21/06 4:47:25 PM8/21/06 4:47:25 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 12

Money and Banking

231

financial capital to businesses, and they finance consumer

purchases of automobiles and other durable goods.

Savings and loan associations (S&Ls), mutual savings

banks, and credit unions supplement the commercial banks

and are known collectively as savings or thrift institutions ,

or simply “thrifts.” Savings and loan associations and mutual

savings banks accept the deposits of households and businesses

and then use the funds to finance housing mortgages and to

provide other loans. Credit unions accept deposits from and

lend to “members,” who usually are a group of people who

work for the same company.

The checkable deposits of banks and thrifts are known

variously as demand deposits, NOW (negotiable order of

withdrawal) accounts, ATS (automatic transfer service)

accounts, and share draft accounts. Their commonality is

that depositors can write checks on them whenever, and in

whatever amount, they choose.

A Qualification We must qualify our discussion in an

important way. Currency and checkable deposits owned by

the government (the U.S. Treasury) and by Federal Reserve

Banks, commercial banks, or other financial institutions are

excluded from M 1 and other measures of the money supply.

A paper dollar in the hands of, say, Emma Buck obvi-

ously constitutes just $1 of the money supply. But if we

counted dollars held by banks as part of the money supply,

the same $1 would count for $2 when it was deposited in a

bank. It would count for a $1 checkable deposit owned by

Buck and also for $1 of currency resting in the bank’s till

or vault. By excluding currency resting in banks in deter-

mining the total money supply, we avoid this problem of

double counting.

Excluding government financial holdings from the

money supply allows for better assessment of the amount

of money available to firms and households for potential

spending. That amount of money and potential spending is

of keen interest to the Federal Reserve in conducting its

monetary policy (a topic we cover in detail in Chapter 14).

Money Definition M2

A second and broader definition of money includes M 1

plus several near-monies. Near-monies are certain highly

liquid financial assets that do not function directly or fully

as a medium of exchange but can be readily converted into

currency or checkable deposits. There are three categories

of near-monies included in the M2 definition of money:

• Savings deposits, including money market deposit

accounts A depositor can easily withdraw funds from

a savings account at a bank or thrift or simply re-

quest that the funds be transferred from a savings ac-

count to a checkable account. A person can also

withdraw funds from a money market deposit

account (MMDA) , which is an interest-bearing

account containing a variety of interest-bearing

short-term securities. MMDAs, however, have a

minimum-balance requirement and a limit on how

often a person can withdraw funds.

• Small (less than $100,000) time deposits Funds from

time deposits become available at their maturity. For

example, a person can convert a 6-month time deposit

(“certificate of deposit,” or “CD”) to currency without

penalty 6 months or more after it has been deposited.

In return for this withdrawal limitation, the financial

institution pays a higher interest rate on such deposits

than it does on its MMDAs. Also, a person can “cash

in” a CD at any time but must pay a severe penalty.

• Money market mutual funds held by individuals By

making a telephone call, using the Internet, or writ-

ing a check for $500 or more, a depositor can redeem

shares in a money market mutual fund (MMMF)

offered by a mutual fund company. Such companies

use the combined funds of individual shareholders to

buy interest-bearing short-term credit instruments

such as certificates of deposit and U.S. government

securities. Then they can offer interest on the

MMMF accounts of the shareholders (depositors)

who jointly own those financial assets. The MMMFs

in M 2 include only the MMMF accounts held by in-

dividuals, not by businesses and other institutions.

All three categories of near-monies imply substantial

liquidity. Thus, in equation form,

Money, M 2 ⫽

M 1 ⫹ savings deposits,

including MMDAs ⫹ small

(less than $100,000) time deposits

⫹ MMMFs held by individuals

In summary, M 2 includes the immediate medium-

of-exchange items (currency and checkable deposits) that

constitute M 1 plus certain near-monies that can be easily

converted into currency and checkable deposits. In Figure

12.1 b we see that the addition of all these items yields an

M 2 money supply that is about five times larger than the

narrower M 1 money supply.

Money Definition MZM

There are other definitions of money, each including or

excluding various categories of near-money. One definition

of increasing importance is MZM (money zero maturity),

reported by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. MZM

focuses exclusively on monetary balances that are immedi-

ately available, at zero cost, for household and business

transactions. Economists make two adjustments to M 2 to

obtain MZM . They

mcc26632_ch12_227-243.indd 231mcc26632_ch12_227-243.indd 231 8/21/06 4:47:25 PM8/21/06 4:47:25 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART FOUR

Money, Banking, and Monetary Policy

232

• Subtract small time deposits because the maturity

(time length until repayment) on deposits is

6 months, 1 year, or some other length beyond in-

stant (zero) maturity. Withdrawal prior to maturity

requires the payment of a substantial financial penalty.

• Add money market mutual fund (MMMF) balances

owned by businesses. Businesses can write checks on

these MMMFs and can move funds to checkable

deposits from them without penalty. Like the

MMMFs held by individuals, the MMMFs held by

businesses are immediately available for purchases.

In equation form,

M 2 ⫺ small ($100,000 or less)

Money MZM ⫽ time deposits ⫹ MMMFs held

by businesses

The advantage of the MZM definition is that it includes

the main items—currency, checkable deposits, MMDAs,

and MMMFs—used on a daily basis to buy goods, services,

and resources. It excludes time deposits, which are nor-

mally used for saving rather than for immediate transac-

tions. In February 2006 MZM was $6934 billion, slightly

larger than M 2 of $6758 billion.

Each of the three definitions of money is useful. The

narrowest definition, M 1, is easiest to understand and is

often cited. But economists generally use the broader

measures M 2 and MZM to measure the nation’s money

supply. Unless stated otherwise, we will dispense with the

M 1, M 2, and MZM distinctions in our subsequent analysis

and simply designate the supply of money as M

s

. Keep in

mind that the M 1 components of the money supply—

currency and checkable deposits—are base items in the

broader M 2 and MZM definitions. Monetary actions that

increase currency and checkable deposits also increase M 2

and MZM , or simply M

s

. (Key Question 4)

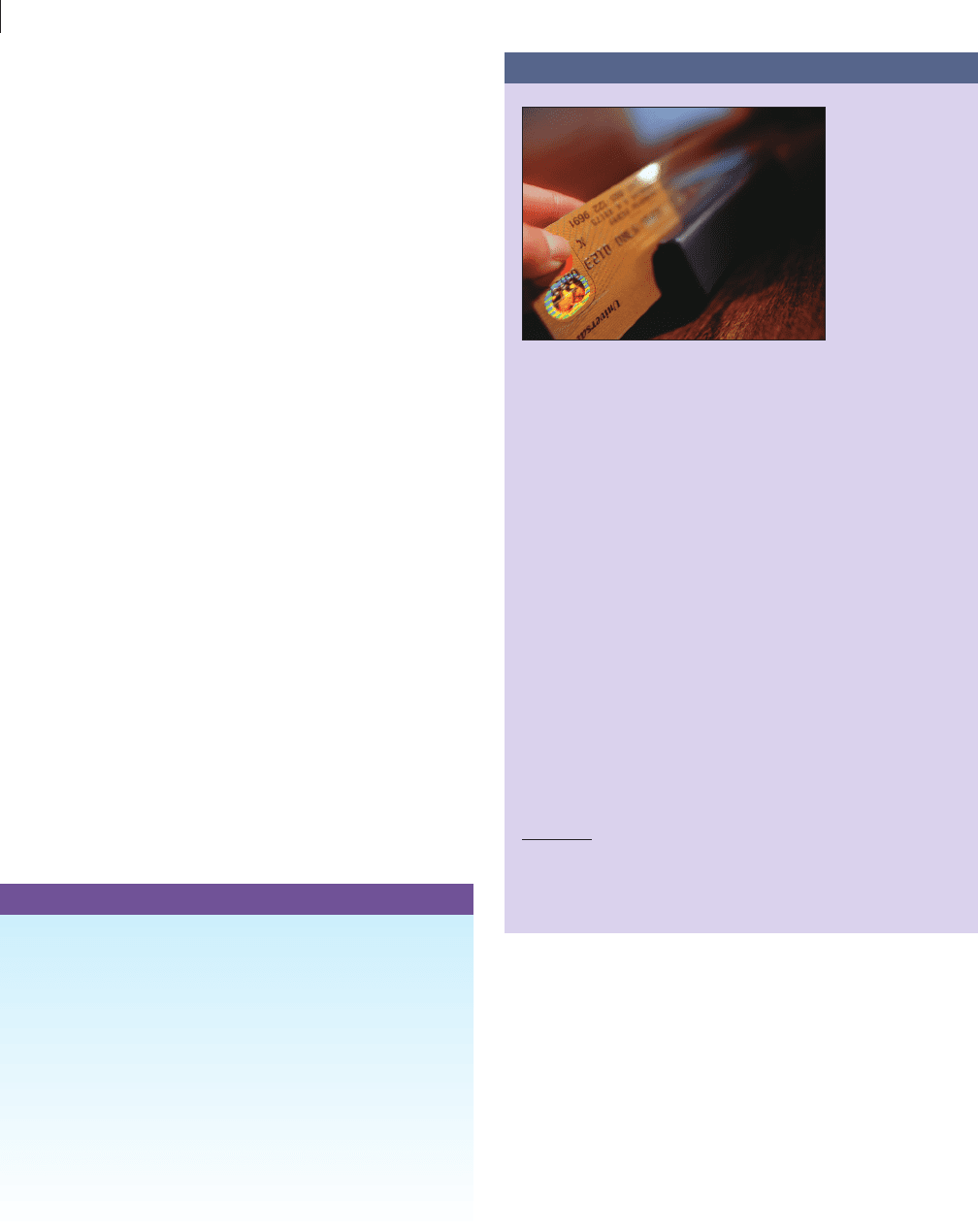

CONSIDER THIS . . .

Are Credit

Cards

Money?

You may wonder

why we have ig-

nored credit

cards such as Visa

and MasterCard

in our discussion

of how the

money supply is

defined. After all, credit cards are a convenient way to buy things

and account for about 25% of the dollar value of all transac-

tions in the United States. The answer is that a credit card is

not money. Rather, it is a convenient means of obtaining a short-

term loan from the financial institution that issued the card.

What happens when you purchase an item with a credit

card? The bank that issued the card will reimburse the store,

charging it a transaction fee, and later you will reimburse the

bank. Rather than reduce your cash or checking account with

each purchase, you bunch your payments once a month. You

may have to pay an annual fee for the services provided, and if

you pay the bank in installments, you will pay a sizable interest

charge on the loan. Credit cards are merely a means of defer-

ring or postponing payment for a short period. Your checking

account balance that you use to pay your credit card bill is

money; the credit card is not money.*

Although credit cards are not money, they allow individuals

and businesses to “economize” in the use of money. Credit

cards enable people to hold less currency in their billfolds and,

prior to payment due dates, fewer checkable deposits in their

bank accounts. Credit cards also help people coordinate the

timing of their expenditures with their receipt of income.

*A bank debit card, however, is very similar to a check in your check-

book. Unlike a purchase with a credit card, a purchase with a debit card

creates a direct “debit” (a subtraction) from your checking account

balance. That checking account balance is money—it is part of M1.

QUICK REVIEW 12.1

• Money serves as a medium of exchange, a unit of account,

and a store of value.

• The narrow M1 definition of money includes currency held

by the public plus checkable deposits in commercial banks

and thrift institutions.

• Thrift institutions as well as commercial banks offer accounts

on which checks can be written.

• The M2 definition of money includes M1 plus savings

deposits, including money market deposit accounts, small

(less than $100,000) time deposits, and money market mutual

fund balances held by individuals.

• Money supply MZM (money zero maturity) adjusts M2 by

subtracting small (less than $100,000) time deposits and adding

money market mutual fund balances held by businesses.

What “Backs” the Money

Supply?

The money supply in the United States essentially is

“backed” (guaranteed) by government’s ability to keep the

value of money relatively stable. Nothing more!

Money as Debt

The major components of the money supply—paper

money and checkable deposits—are debts, or promises to

pay. In the United States, paper money is the circulating

mcc26632_ch12_227-243.indd 232mcc26632_ch12_227-243.indd 232 9/8/06 5:54:54 PM9/8/06 5:54:54 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES