McConnell С., Campbell R. Macroeconomics: principles, problems, and policies, 17th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PART FIVE

Long-Run Perspectives and

Macroeconomic Debates

15 EXTENDING THE ANALYSIS OF

AGGREGATE SUPPLY

16 ECONOMIC GROWTH

16W THE ECONOMICS OF DEVELOPING

COUNTRIES

17 DISPUTES OVER MACRO THEORY

AND POLICY

mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 284mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 284 9/1/06 3:17:01 PM9/1/06 3:17:01 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

IN THIS CHAPTER YOU WILL LEARN:

• About the relationship between short-run

aggregate supply and long-run aggregate supply.

• How to apply the “extended” (short-run/long-run)

AD-AS model to inflation, recessions, and

unemployment.

• About the short-run tradeoff between inflation and

unemployment (the Phillips Curve).

• Why there is no long-run tradeoff between inflation

and unemployment.

• The relationship between tax rates, tax revenues,

and aggregate supply.

Extending the Analysis of

Aggregate Supply

During the early years of the Great Depression, many economists suggested that the economy would

correct itself in the long run without government intervention. To this line of thinking, economist

John Maynard Keynes remarked, “In the long run we are all dead!”

For several decades following the Great Depression, macroeconomic economists understandably

focused on refining fiscal policy and monetary policy to smooth business cycles and address the

problems of unemployment and inflation. The main emphasis was on short-run problems and policies

associated with the business cycle.

But over people’s lifetimes, and from generation to generation, the long run is tremendously impor-

tant for economic well-being. For that reason, macroeconomists have refocused attention on long-

run macroeconomic adjustments, processes, and outcomes. As we will see in this and the next three

15

mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 285mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 285 9/1/06 3:17:04 PM9/1/06 3:17:04 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART FIVE

Long-Run Perspectives and Macroeconomic Debates

286

From Short Run to Long Run

Until now we have assumed the aggregate supply curve

remains stable when the aggregate demand curve shifts.

For example, an increase in aggregate demand along the

upsloping short-run aggregate supply curve raises both

the price level and real output. That analysis is accurate

and realistic for the short run , which, you may recall from

Chapter 10, is a period in which nominal wages (and other

input prices) do not respond to price-level changes.

There are at least two reasons why nominal wages may

for a time be unresponsive to changes in the price level:

• Workers may not immediately be aware of the extent

to which inflation (or deflation) has changed their

real wages, and thus they may not adjust their labor

supply decisions and wage demands accordingly.

• Many employees are hired under fixed-wage contracts.

For unionized employees, for example, nominal wages

are spelled out in their collective bargaining agree-

ments for perhaps 2 or 3 years. Also, most managers

and many professionals receive set salaries established

in annual contracts. For them, nominal wages remain

constant for the life of the contracts, regardless of

changes in the price level.

In such cases, price-level changes do not immediately give

rise to changes in nominal wages. Instead, significant peri-

ods of time may pass before such adjustments occur.

Once contracts have expired and nominal wage adjust-

ments have been made, the economy enters the long run .

Recall that this is the period in which nominal wages are

fully responsive to previous changes in the price level. As

time passes, workers gain full information about price-level

changes and how those changes affect their real wages. For

example, suppose that Jessica received an hourly nominal

wage of $10 when the price index was 100 (or, in decimals,

1.0) and that her real wage was also $10 (⫽ $10 of nominal

wage divided by 1.0). But when the price level rises to, say,

120, Jessica’s $10 real wage declines to $8.33 (⫽ $10兾1.2).

As a result, she and other workers will adjust their labor

supply and wage demands such that their nominal wages

eventually will rise to restore the purchasing power of an

hour of work. In our example, Jessica’s nominal wage will

increase from $10 to $12, returning her real wage to $10

(⫽ $12兾1.2). But that adjustment will take time.

Short-Run Aggregate Supply

Our immediate objective is to demonstrate the relationship

between short-run aggregate supply and long-run aggregate

supply. We begin by briefly reviewing short-run aggregate

supply.

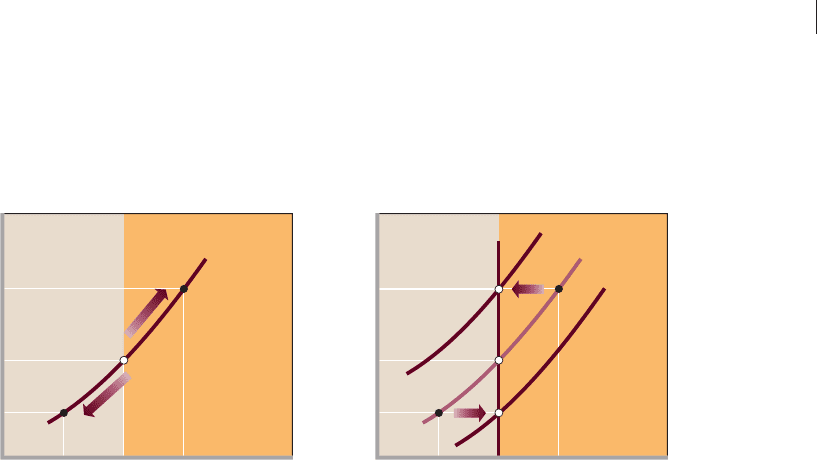

Consider the short-run aggregate supply curve AS

1

in

Figure 15.1 a. This curve is based on three assumptions:

(1) The initial price level is P

1

, (2) firms and workers have

established nominal wages on the expectation that this price

level will persist, and (3) the price level is flexible both up-

ward and downward. Observe from point a

1

that at price

level P

1

the economy is operating at its full-employment

output Q

f

. This output is the real production forthcoming

when the economy is operating at its natural rate of unem-

ployment (or potential output.).

Now let’s review the short-run effects of changes in the

price level, say, from P

1

to P

2

in Figure 15.1 a. The higher

prices associated with price level P

2

increase firms’ reve-

nues, and because their nominal wages remain unchanged,

their profits rise. Those higher profits lead firms to increase

their output from Q

f

to Q

2

, and the economy moves from

a

1

to a

2

on aggregate supply AS

1

. At output Q

2

the economy

is operating beyond its full-employment output. The firms

make this possible by extending the work hours of part-time

and full-time workers, enticing new workers such as home-

makers and retirees into the labor force, and hiring and

training the structurally unemployed. Thus, the nation’s

unemployment rate declines below its natural rate.

How will the firms respond when the price level falls,

say, from P

1

to P

3

in Figure 15.1 a? Because the prices they

receive for their products are lower while the nominal

wages they pay workers are not, firms discover that their

revenues and profits have diminished or disappeared. So

they reduce their production and employment, and, as

shown by the movement from a

1

to a

3

, real output falls to

chapters (one is at our Internet site only), the renewed emphasis on the long run has produced

significant insights on aggregate supply, economic growth, and economic development. We will also

see that it has renewed historical debates over the causes of macro instability and the effectiveness of

stabilization policy.

Our goals in this chapter are to extend the analysis of aggregate supply to the long run, examine

the inflation-unemployment relationship, and evaluate the effect of taxes on aggregate supply. The

latter is a key concern of so-called supply-side economics .

286

mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 286mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 286 9/1/06 3:17:08 PM9/1/06 3:17:08 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 15

Extending the Analysis of Aggregate Supply

287

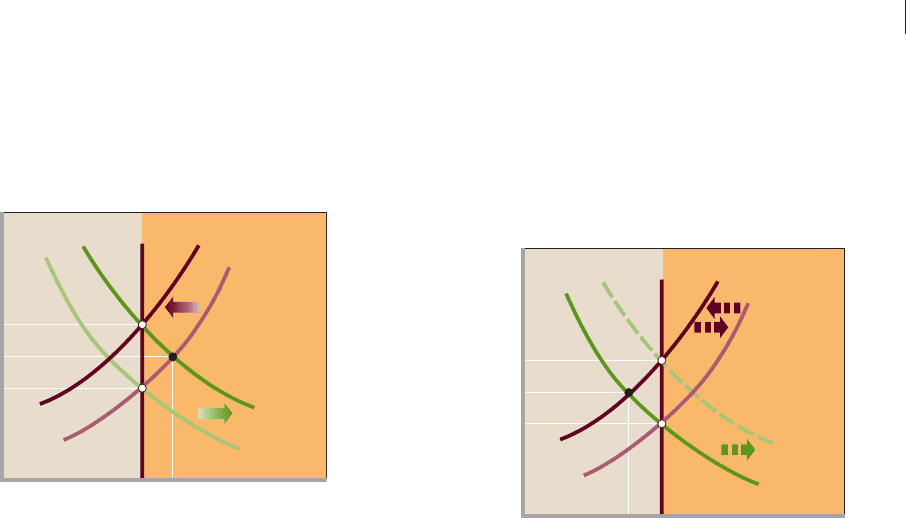

FIGURE 15.1 Short-run and long-run aggregate supply. (a) In the short run, nominal wages do not

respond to price-level changes and based on the expectation that price level P

1

will continue. An increase in the price level

from P

1

to P

2

increases profits and output, moving the economy from a

1

to a

2

; a decrease in the price level from P

1

to P

3

reduces profits and real output, moving the economy from a

1

to a

3

. The short-run aggregate supply curve therefore slopes

upward. (b) In the long run, a rise in the price level results in higher nominal wages and thus shifts the short-run aggregate

supply curve to the left. Conversely, a decrease in the price level reduces nominal wages and shifts the short-run aggregate

supply curve to the right. After such adjustments, the economy obtains equilibrium of points such as b

1

and c

1

. Thus, the

long-run aggregate supply curve is vertical at the full-employment output.

Q

3

AS

1

a

3

a

1

a

2

Q

2

Q

f

Real domestic output

0

(a)

Short-run a

gg

re

g

ate su

pp

l

y

P

1

P

3

P

2

Price level

AS

1

AS

2

AS

LR

AS

3

a

3

a

1

a

2

b

1

c

1

Q

f

Real domestic output

0

(b)

Lon

g

-run a

gg

re

g

ate su

pp

l

y

P

1

P

3

P

2

Price level

Q

3

. Increased unemployment and a higher unemployment

rate accompany the decline in real output. At output Q

3

the unemployment rate is greater than the natural rate of

unemployment associated with output Q

f

.

Long-Run Aggregate Supply

The outcomes are different in the long run. To see why,

we need to extend the analysis of aggregate supply to ac-

count for changes in nominal wages that occur in response

to changes in the price level. That will enable us to derive

the economy’s long-run aggregate supply curve.

By definition, nominal wages in the long run are fully

responsive to changes in the price level. We illustrate the

implications for aggregate supply in Figure 15.1 b. Again,

suppose that the economy is initially at point a

1

( P

1

and

Q

f

). As we just demonstrated, an increase in the price level

from P

1

to P

2

will move the economy from point a

1

to a

2

along the short-run aggregate supply curve AS

1

. In the

long run, however, workers discover that their real wages

(their constant nominal wages divided by the price level)

have declined because of this increase in the price level.

They restore their previous level of real wages by gaining

nominal wage increases. Because nominal wages are one of

the determinants of aggregate supply (see Figure 10.5 ), the

short-run supply curve then shifts leftward from AS

1

to

AS

2

, which now reflects the higher price level P

2

and the

new expectation that P

2

, not P

1

, will continue. The left-

ward shift in the short-run aggregate supply curve to AS

2

moves the economy from a

2

to b

1

. Real output falls back to

its full-employment level Q

f

, and the unemployment rate

rises to its natural rate.

What is the long-run outcome of a decrease in the price

level? Assuming eventual downward wage flexibility, a de-

cline in the price level from P

1

to P

3

in Figure 15.1 b works

in the opposite way from a price-level increase. At first the

economy moves from point a

1

to a

3

on AS

1

. Profits are

squeezed or eliminated because prices have fallen and nom-

inal wages have not. But this movement along AS

1

is the

short-run supply response. With enough time the lower

price level P

3

(which has increased real wages) results in a

drop in nominal wages such that the original real wages are

restored. Lower nominal wages shift the short-run aggre-

gate supply curve rightward from AS

1

to AS

3

, and real out-

put returns to its full-employment level of Q

f

at point c

1

.

By tracing a line between the long-run equilibrium

points b

1

, a

1

, and c

1

, we obtain a long-run aggregate supply

curve. Observe that it is vertical at the full-employment

level of real GDP. After long-run adjustments in nominal

wages, real output is Q

f

regardless of the specific price

level. (Key Question 3)

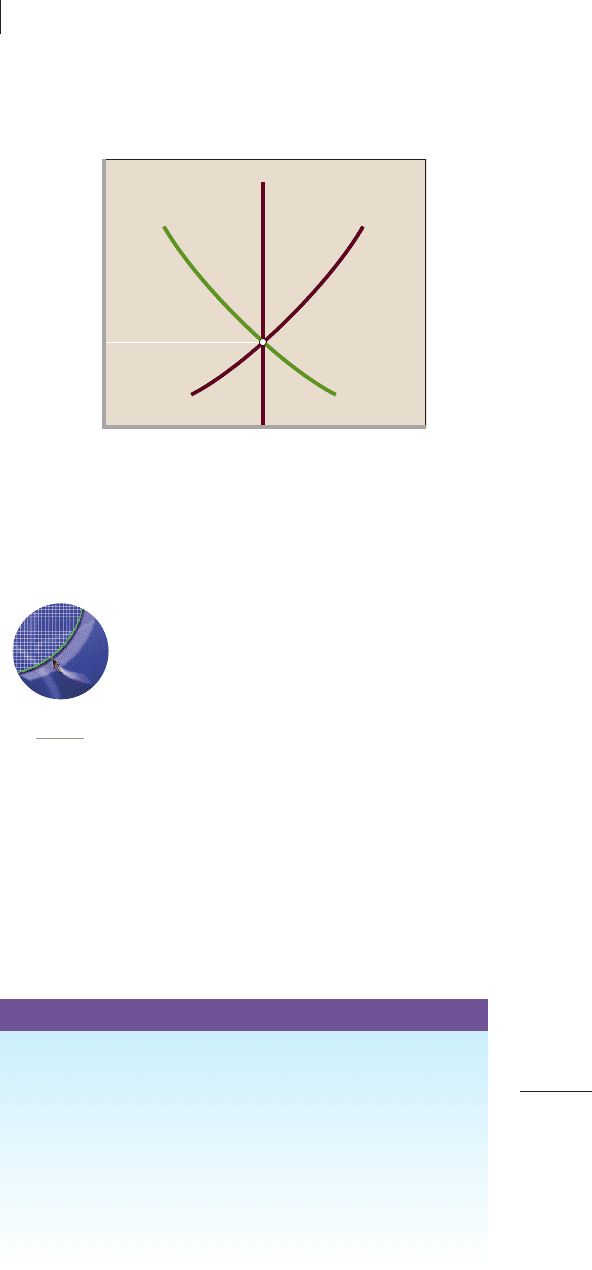

Long-Run Equilibrium in

the AD-AS Model

Figure 15.2 helps us understand the long-run equilibrium in

the AD-AS model, now extended to include the distinction

between short-run and long-run aggregate supply. (Hereaf-

ter, we will refer to this model as the extended AD-AS model,

mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 287mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 287 9/1/06 3:17:08 PM9/1/06 3:17:08 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART FIVE

Long-Run Perspectives and Macroeconomic Debates

288

with “extended” referring to the inclusion of both the short-

run and the long-run aggregate supply curves.)

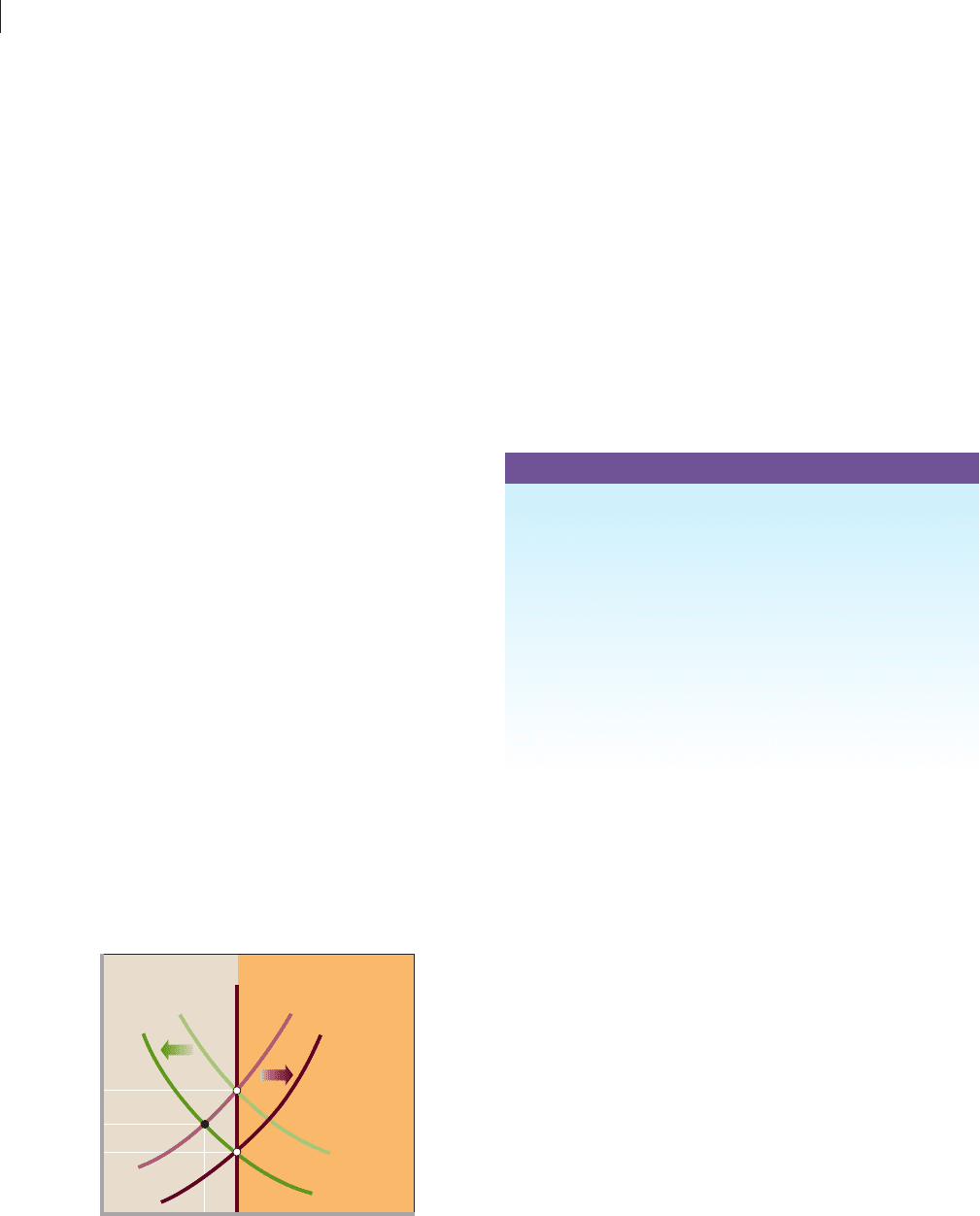

In the short run, equilibrium occurs wherever the

downsloping aggregate demand curve and upsloping

short-run aggregate supply curve intersect.

This can be at any level of output, not sim-

ply the full-employment level. Either a

negative GDP or a positive GDP gap is

possible in the short run.

But in the long run, the short-run ag-

gregate supply curve adjusts as we just de-

scribed. After those adjustments, long-run

equilibrium occurs where the aggregate de-

mand curve, vertical long-run aggregate supply curve, and

short-run aggregate supply curve all intersect. Figure 15.2

shows the long-run outcome. Equilibrium occurs at point a ,

where AD

1

intersects both AS

LR

and AS

1

, and the economy

achieves its full-employment (or potential) output, Q

f

. At

long-run equilibrium price level P

1

and output level Q

f

, there

is neither a negative GDP gap nor a positive GDP gap.

Applying the Extended

AD-AS Model

The extended AD-AS model helps clarify the long-run

aspects of demand-pull inflation, cost-push inflation, and

recession.

Demand-Pull Inflation in the

Extended AD-AS Model

Recall that demand-pull inflation occurs when an increase in

aggregate demand pulls up the price level. Earlier, we depicted

this inflation by shifting an aggregate demand curve right-

ward along a stable aggregate supply curve (see Figure 10.7).

In our more complex version of aggregate supply,

however, an increase in the price level eventually leads to

an increase in nominal wages and thus a leftward shift of

the short-run aggregate supply curve. This is shown

in Figure 15.3 , where we initially suppose the price level is

P

1

at the intersection of aggregate demand curve AD

1

,

short-run supply curve AS

1

, and long-run aggregate supply

curve AS

LR

. Observe that the economy is achieving its

full-employment real output Q

f

at point a.

Now consider the effects of an increase in aggregate

demand as represented by the rightward shift from AD

1

to

AD

2

. This shift might result from any one of a number of

factors, including an increase in investment spending and

a rise in net exports. Whatever its cause, the increase in

aggregate demand boosts the price level from P

1

to P

2

and

expands real output from Q

f

to Q

2

at point b . There, a pos-

itive GDP gap of Q

2

⫺ Q

f

occurs.

So far, none of this is new to you. But now the distinction

between short-run aggregate supply and long-run aggregate

supply becomes important. Once workers have realized that

their real wages have declined and their existing contracts

have expired, nominal wages will rise. As they do, the short-

run aggregate supply curve will ultimately shift leftward such

that it intersects long-run aggregate supply at point c.

1

There;

the economy has reestablished long-run equilibrium, with

the price level and real output now P

3

and Q

f

, respectively.

Only at point c does the new aggregate demand curve AD

2

intersect both the short-run aggregate supply curve AS

2

and

the long-run aggregate supply curve AS

LR

.

G 15.1

Extended AD-AS

model

QUICK REVIEW 15.1

• The short-run aggregate supply curve has a positive slope

because nominal wages do not respond to the price-level

changes.

• The long-run aggregate supply curve is vertical, because

nominal wages eventually change by the same relative

amount as changes in the price level.

• The long-run equilibrium GDP and price level occur at the

intersection of the aggregate demand curve, the long-run

aggregate supply curve, and the short-run aggregate supply

curve.

1

We say “ultimately” because the initial leftward shift in short-run aggre-

gate supply will intersect the long-run aggregate supply curve AS

LR

at

price level P

2

(review Figure 15.1b). But the intersection of AD

2

and this

new short-run aggregate supply curve (not shown) will produce a price

level above P

2

. (You may want to pencil this in to make sure that you un-

derstand this point.) Again nominal wages will rise, shifting the short-run

aggregate supply curve farther leftward. The process will continue until

the economy moves to point c, where the short-run aggregate supply curve

is AS

2

, the price level is P

3

, and real output is Q

f

.

FIGURE 15.2 Equilibrium in the extended

AD-AS model. The long-run equilibrium price level P

1

and

level of real output Q

f

occur at the intersection of the aggregate

demand curve AD

1

, the long-run aggregate supply curve AS

LR

,

and the short-run aggregate supply curve AS

1.

P

1

0 Q

f

Price level

AS

LR

Real domestic out

p

ut

a

AD

1

AS

1

mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 288mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 288 9/1/06 3:17:09 PM9/1/06 3:17:09 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 15

Extending the Analysis of Aggregate Supply

289

FIGURE 15.3 Demand-pull inflation in the

extended AD-AS model. An increase in aggregate

demand from AD

1

to AD

2

drives up the price level and increases

real output in the short run. But in the long run, nominal wages

rise and the short-run aggregate supply curve shifts leftward, as

from AS

1

to AS

2

. Real output then returns to its prior level, and

the price level rises even more. In this scenario, the economy

moves from a to b and then eventually to c.

P

3

P

2

P

1

Price level

Q

f

Q

2

Real domestic output

0

AS

2

AS

LR

a

b

c

AS

1

AD

2

AD

1

In the short run, demand-pull inflation drives up the

price level and increases real output; in the long run, only

the price level rises. In the long run, the initial increase in

aggregate demand has moved the economy along its verti-

cal aggregate supply curve AS

LR

. For a while, an economy

can operate beyond its full-employment level of output.

But the demand-pull inflation eventually causes adjust-

ments of nominal wages that return the economy to its

full-employment output Q

f

.

Cost-Push Inflation in the

Extended AD-AS Model

Cost-push inflation arises from factors that increase the cost

of production at each price level, shifting the aggregate sup-

ply curve leftward and raising the equilibrium price level.

Previously (Figure 10.9), we considered cost-push inflation

using only the short-run aggregate supply curve. Now we

want to analyze that type of inflation in its long-run context.

Analysis Look at Figure 15.4 , in which we again assume

that the economy is initially operating at price level P

1

and

output level Q

f

(point a ). Suppose that international oil pro-

ducers agree to reduce the supply of oil to boost its price by,

say, 100 percent. As a result, the per-unit production cost of

producing and transporting goods and services rises sub-

stantially in the economy represented by Figure 15.4 .

This increase in per-unit production costs shifts the short-

run aggregate supply curve to the left, as from AS

1

to AS

2

,

and the price level rises from P

1

to P

2

(as seen by comparing

points a and b ). In this case, the leftward shift of the aggre-

gate supply curve is not a response to a price-level increase, as

it was in our previous discussions of demand-pull inflation;

it is the initiating cause of the price-level increase.

Policy Dilemma Cost-push inflation creates a di-

lemma for policymakers. Without some expansionary stabi-

lization policy, aggregate demand in Figure 15.4 remains in

place at AD

1

and real output declines from Q

f

to Q

2

. Gov-

ernment can counter this recession, negative GDP gap, and

attendant high unemployment by using fiscal policy and

monetary policy to increase aggregate demand to AD

2

. But

there is a potential policy trap here: An increase in aggre-

gate demand to AD

2

will further raise inflation by increas-

ing the price level from P

2

to P

3

(a move from point b to c ).

Suppose the government recognizes this policy trap

and decides not to increase aggregate demand from AD

1

to

AD

2

(you can now disregard the dashed AD

2

curve) and

instead decides to allow a cost-push-created recession to

run its course. How will that happen? Widespread layoffs,

plant shutdowns, and business failures eventually occur.

At some point the demand for oil, labor, and other inputs

will decline so much that oil prices and nominal wages will

decline. When that happens, the initial leftward shift of the

short-run aggregate supply curve will reverse itself. That is,

the declining per-unit production costs caused by the reces-

sion will shift the short-run aggregate supply curve right-

ward from AS

2

to AS

1

. The price level will return to P

1

, and

the full-employment level of output will be restored at Q

f

(point a on the long-run aggregate supply curve AS

LR

).

FIGURE 15.4 Cost-push inflation in the

extended AD-AS model. Cost-push inflation occurs

when the short-run aggregate supply curve shifts leftward, as

from AS

1

to AS

2

. If government counters the decline in real

output by increasing aggregate demand to the broken line, the

price level rises even more. That is, the economy moves in steps

from a to b to c. In contrast, if government allows a recession

to occur, nominal wages eventually fall and the aggregate supply

curve shifts back rightward to its original location. The economy

moves from a to b and eventually back to a.

a

b

c

AS

1

AS

2

AD

2

AD

1

P

3

P

2

P

1

Price level

Q

f

Q

2

0

AS

LR

Real domestic output

mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 289mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 289 9/1/06 3:17:09 PM9/1/06 3:17:09 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART FIVE

Long-Run Perspectives and Macroeconomic Debates

290

This analysis yields two generalizations:

• If the government attempts to maintain full

employment when there is cost-push inflation, an

inflationary spiral may occur.

• If the government takes a hands-off approach to cost-

push inflation, a recession will occur. Although the

recession eventually may undo the initial rise in per-unit

production costs, the economy in the meantime will ex-

perience high unemployment and a loss of real output.

Recession and the Extended

AD-AS Model

By far the most controversial application of the extended

AD-AS model is its application to recession (or depres-

sion) caused by decreases in aggregate demand. We will

look at this controversy in detail in Chapter 17; here we

simply identify the key point of contention.

Suppose in Figure 15.5 that aggregate demand initially

is AD

1

and that the short-run and long-run aggregate supply

curves are AS

1

and AS

LR

, respectively. Therefore, as shown

by point a, the price level is P

1

and output is Q

f

. Now sup-

pose that investment spending declines dramatically, reduc-

ing aggregate demand to AD

2

. Observe that real output

declines from Q

f

to Q

1

, indicating that a recession has

occurred. But if we make the controversial assumption that

prices and wages are flexible downward, the price level falls

from P

1

to P

2

. The lower price level increases real wages for

people who are still working, since each dollar of nominal

wage has greater purchasing power. Eventually, nominal

wages themselves fall to restore the previous real wage; when

that happens, the short-run aggregate supply curve

shifts rightward from AS

1

to AS

2

. The negative GDP gap

evaporates without the need for expansionary fiscal or mon-

etary policy, since real output expands from Q

1

(point b ) back

to Q

f

(point c ). The economy is again located on its long-run

aggregate supply curve AS

LR

, but now at lower price level P

3

.

There is much disagreement about this hypothetical

scenario. The key point of dispute is how long it would

take in the real world for the necessary downward price and

wage adjustments to occur to regain the full-employment

level of output. For now, suffice it to say that most econo-

mists believe that if such adjustments are forthcoming, they

will occur only after the economy has experienced a rela-

tively long-lasting recession with its accompanying high

unemployment and large loss of output. Therefore, econo-

mists recommend active monetary policy, and perhaps fiscal

policy, to counteract recessions. (Key Question 4)

FIGURE 15.5 Recession in the extended AD-

AS model. A recession occurs when aggregate demand

shifts leftward, as from AD

1

to AD

2

. If prices and wages are

downwardly flexible, the price level falls from P

1

to P

2

. That

decline in the price level eventually reduces nominal wages, and

this shifts the aggregate supply curve from AS

1

to AS

2

. The price

level declines to P

3

, and real output increases back to Q

f

. The

economy moves from point a to b and then eventually to c.

Price level

Q

f

Q

1

Real domestic output

0

c

b

a

AS

2

AS

1

AD

1

AD

2

P

1

P

2

P

3

AS

LR

QUICK REVIEW 15.2

• In the short run, demand-pull inflation raises both the price

level and real output; in the long run, nominal wages rise, the

short-run aggregate supply curve shifts to the left, and only

the price level increases.

• Cost-push inflation creates a policy dilemma for the

government: If it engages in an expansionary policy to

increase output, an inflationary spiral may occur; if it does

nothing, a recession will occur.

• In the short run, a decline in aggregate demand reduces real

output (creates a recession); in the long run, prices and

nominal wages presumably fall, the short-run aggregate

supply curve shifts to the right, and real output returns to its

full-employment level.

The Inflation-Unemployment

Relationship

Because both low inflation rates and low unemployment

rates are major economic goals, economists are vitally in-

terested in their relationship. Are low unemployment and

low inflation compatible goals or conflicting goals? What

explains situations in which high unemployment and high

inflation coexist?

The extended AD-AS model supports three signifi-

cant generalizations relating to these questions:

• Under normal circumstances, there is a short-run

tradeoff between the rate of inflation and the rate of

unemployment.

• Aggregate supply shocks can cause both higher rates

of inflation and higher rates of unemployment.

• There is no significant tradeoff between inflation and

unemployment over long periods of time.

Let’s examine each of these generalizations.

mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 290mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 290 9/1/06 3:17:09 PM9/1/06 3:17:09 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 15

Extending the Analysis of Aggregate Supply

291

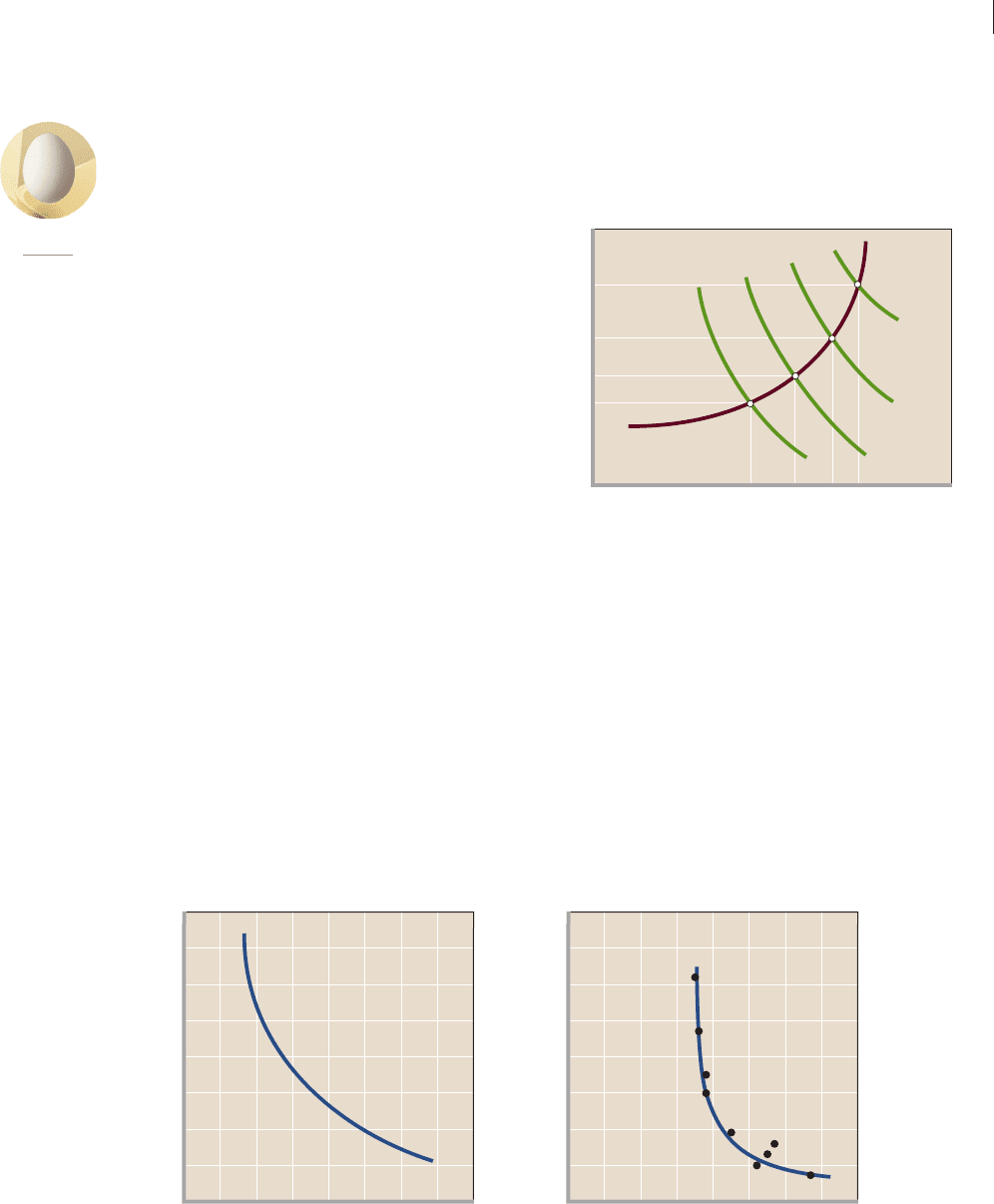

The Phillips Curve

We can demonstrate the short-run tradeoff between the rate

of inflation and the rate of unemployment

through the Phillips Curve , named after

A. W. Phillips, who developed the idea in

Great Britain. This curve, generalized in

Figure 15.6a , suggests an inverse relationship

between the rate of inflation and the rate of

unemployment. Lower unemployment rates

(measured as leftward movements on the

horizontal axis) are associated with higher rates of inflation

(measured as upward movements on the vertical axis).

The underlying rationale of the Phillips Curve be-

comes apparent when we view the short-run aggregate

supply curve in Figure 15.7 and perform a simple mental

experiment. Suppose that in some short-run period aggre-

gate demand expands from AD

0

to AD

2

, either because

firms decided to buy more capital goods or the govern-

ment decided to increase its expenditures. Whatever the

cause, in the short run the price level rises from P

0

to P

2

and real output rises from Q

0

to Q

2

. A decline in the un-

employment rate accompanies the increase in real output.

Now let’s compare what would have happened if the

increase in aggregate demand had been larger, say, from

AD

0

to AD

3

. The new equilibrium tells us that the amount

of inflation and the growth of real output would both have

been greater (and that the unemployment rate would have

been lower). Similarly, suppose aggregate demand during

the year had increased only modestly, from AD

0

to AD

1

.

Compared with our shift from AD

0

to AD

2

, the amount of

inflation and the growth of real output would have been

smaller (and the unemployment rate higher).

The generalization we draw from this mental experi-

ment is this: Assuming a constant short-run aggregate

supply curve, high rates of inflation are accompanied by

low rates of unemployment, and low rates of inflation are

accompanied by high rates of unemployment. Other things

equal, the expected relationship should look something

like Figure 15.6a.

O 15.1

Phillips Curve

FIGURE 15.7 The short-run effect of changes in

aggregate demand on real output and the price

level. Comparing the effects of various possible increases in

aggregate demand leads to the conclusion that the larger the increase

in aggregate demand, the higher the rate of inflation and the greater

the increase in real output. Because real output and the unemployment

rate move in opposite directions, we can generalize that, given short-

run aggregate supply, high rates of inflation should be accompanied by

low rates of unemployment.

P

2

P

3

P

1

P

0

Q

1

Q

0

Q

2

Q

3

0

AD

2

AD

1

AD

0

AD

3

AS

Real domestic output

Price level

FIGURE 15.6 The Phillips Curve: concept and empirical data. (a) The Phillips Curve relates annual rates

of inflation and annual rates of unemployment for a series of years. Because this is an inverse relationship, there presumably is a

tradeoff between unemployment and inflation. (b) Data points for the 1960s seemed to confirm the Phillips Curve concept.

(Note: Inflation rates are on a December-to-December basis.)

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

Unemployment rate (percent)

(a)

The concept

0 1234567

Annual rate of inflation

(percent)

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

Unemployment rate (percent)

(b)

Data for the 1960s

0 123456

61

7

Annual rate of inflation

(percent)

62

63

64

65

66

68

69

67

Phillips

Curve

mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 291mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 291 9/1/06 3:17:10 PM9/1/06 3:17:10 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART FIVE

Long-Run Perspectives and Macroeconomic Debates

292

Figure 15.6 b reveals that the facts for the 1960s nicely

fit the theory. On the basis of that evidence and evidence

from other countries, most economists concluded there

was a stable, predictable tradeoff between unemployment

and inflation. Moreover, U.S. economic policy was built on

that supposed tradeoff. According to this thinking, it was

impossible to achieve “full employment without inflation”:

Manipulation of aggregate demand through fiscal and

monetary measures would simply move the economy along

the Phillips Curve. An expansionary fiscal and monetary

policy that boosted aggregate demand and lowered the un-

employment rate would simultaneously increase inflation.

A restrictive fiscal and monetary policy could be used to

reduce the rate of inflation but only at the cost of a higher

unemployment rate and more forgone production. Society

had to choose between the incompatible goals of price sta-

bility and full employment; it had to decide where to locate

on its Phillips Curve.

For reasons we will soon see, today’s economists reject

the idea of a stable, predictable Phillips Curve. Neverthe-

less, they agree there is a short-run tradeoff between unem-

ployment and inflation. Given aggregate supply, increases

in aggregate demand increase real output and reduce the

unemployment rate. As the unemployment rate falls and

dips below the natural rate, the excessive spending produces

demand-pull inflation. Conversely, when recession sets in

and the unemployment rate increases, the weak aggregate

demand that caused the recession also leads to lower infla-

tion rates.

Periods of exceptionally low unemployment rates and

inflation rates do occur, but only under special sets of

economic circumstances. One such period was the late

1990s, when faster productivity growth increased aggre-

gate supply and fully blunted the inflationary impact of

rapidly rising aggregate demand (review Figure 10.10).

Aggregate Supply Shocks and the

Phillips Curve

The unemployment-inflation experience of the 1970s and

early 1980s demolished the idea of an always-stable

Phillips Curve. In Figure 15.8 we show the Phillips Curve

for the 1960s in blue and then add the data points for 1970

through 2005. Observe that in most of the years of the 1970s

and early 1980s the economy experienced both higher infla-

tion rates and higher unemployment rates than it did in the

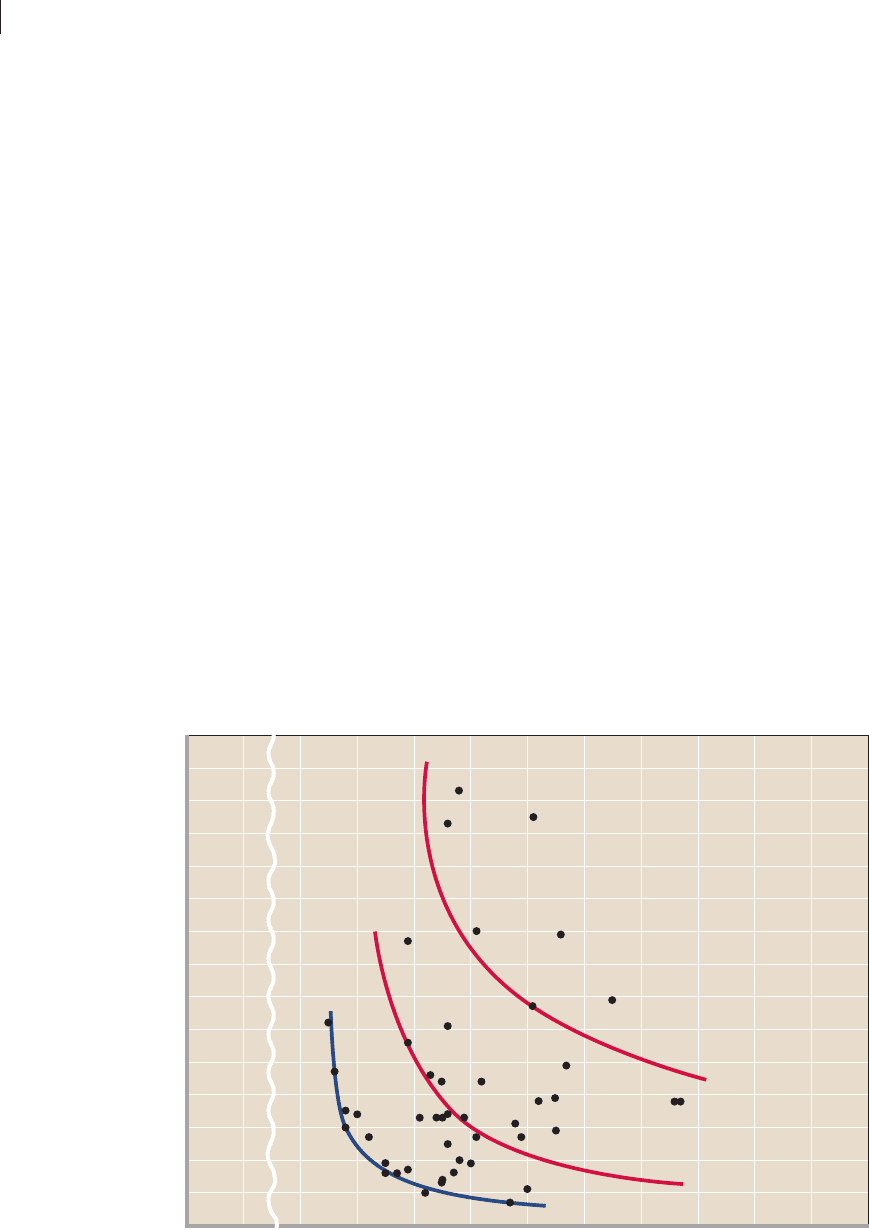

FIGURE 15.8 Inflation rates and unemployment rates, 1960–2005. A series of aggregate supply shocks

in the 1970s resulted in higher rates of inflation and higher rates of unemployment. So data points for the 1970s and 1980s

tended to be above and to the right of the Phillips Curve for the 1960s. In the 1990s the inflation-unemployment data points

slowly moved back toward the original Phillips Curve. Points for the late 1990s and 2000s are similar to those from the earlier

era. (Note: Inflation rates are on a December-to-December basis.)

10 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Unemployment rate (percent)

Annual rate of inflation (percent)

97

02

03

0405

61

62

60

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

71

72

96

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

70

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

89

88

80

92

94

95

00

01

98

99

93

90

91

mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 292mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 292 9/1/06 3:17:10 PM9/1/06 3:17:10 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 15

Extending the Analysis of Aggregate Supply

293

1960s. In fact, inflation and unemployment rose simultane-

ously in some of those years. This condition is called stag-

flation —a media term that combines the words “stagnation”

and “inflation.” If there still was any such thing as a Phillips

Curve, it had clearly shifted outward, perhaps as shown.

Adverse Aggregate Supply Shocks The

Phillips data points for the 1970s and early 1980s support

our second generalization: Aggregate supply shocks can

cause both higher rates of inflation and higher rates of un-

employment. A series of adverse aggregate supply

shocks —sudden, large increases in resource costs that jolt

an economy’s short-run aggregate supply curve leftward—

hit the economy in the 1970s and early 1980s. The most

significant of these shocks was a quadrupling of oil prices

by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries

(OPEC). Consequently, the cost of producing and distrib-

uting virtually every product and service rose rapidly.

(Other factors working to increase U.S. costs during this

period included major agricultural shortfalls, a greatly de-

preciated dollar, wage hikes previously held down by

wage-price controls, and declining productivity.)

These shocks shifted the aggregate supply curve to

the left and distorted the usual inflation-unemployment

relationship. Remember that we derived the inverse

relationship between the rate of inflation and the unem-

ployment rate shown in Figure 15.6a by shifting the

aggregate demand curve along a stable short-run aggre-

gate supply curve ( Figure 15.7 ). But the cost-push infla-

tion model shown in Figure 15.4 tells us that a leftward

shift of the short-run aggregate supply curve increases the

price level and reduces real output (and increases the

unemployment rate). This, say most economists, is what

happened in two periods in the 1970s. The U.S. unem-

ployment rate shot up from 4.9 percent in 1973 to 8.3 per-

cent in 1975, contributing to a significant decline in real

GDP. In the same period, the U.S. price level rose by

21 percent. The stagflation scenario recurred in 1978,

when OPEC increased oil prices by more than

100 percent. The U.S. price level rose by 26 percent over

the 1978–1980 period, while unemployment increased

from 6.1 to 7.1 percent.

Stagflation’s Demise Another look at Figure 15.8

reveals a generally inward movement of the inflation-

unemployment points between 1982 and 1989. By 1989

the lingering effects of the early period had subsided. One

precursor to this favorable trend was the deep recession of

1981–1982, largely caused by a restrictive monetary policy

aimed at reducing double-digit inflation. The recession

upped the unemployment rate to 9.5 percent in 1982.

With so many workers unemployed, those who were

working accepted smaller increases in their nominal

wages—or, in some cases, wage reductions—in order to

preserve their jobs. Firms, in turn, restrained their price

increases to try to retain their relative shares of a greatly

diminished market.

Other factors were at work. Foreign competition

throughout this period held down wage and price hikes in

several basic industries such as automobiles and steel. De-

regulation of the airline and trucking industries also

resulted in wage reductions or so-called wage givebacks. A

significant decline in OPEC’s monopoly power and a

greatly reduced reliance on oil in the production process

produced a stunning fall in the price of oil and its deriva-

tive products, such as gasoline.

All these factors combined to reduce per-unit pro-

duction costs and to shift the short-run aggregate supply

curve rightward (as from AS

2

to AS

1

in Figure 15.4 ). Em-

ployment and output expanded, and the unemployment

rate fell from 9.6 percent in 1983 to 5.3 percent in 1989.

Figure 15.8 reveals that the inflation-unemployment

points for recent years are closer to the points associated

with the Phillips Curve of the 1960s than to the points in

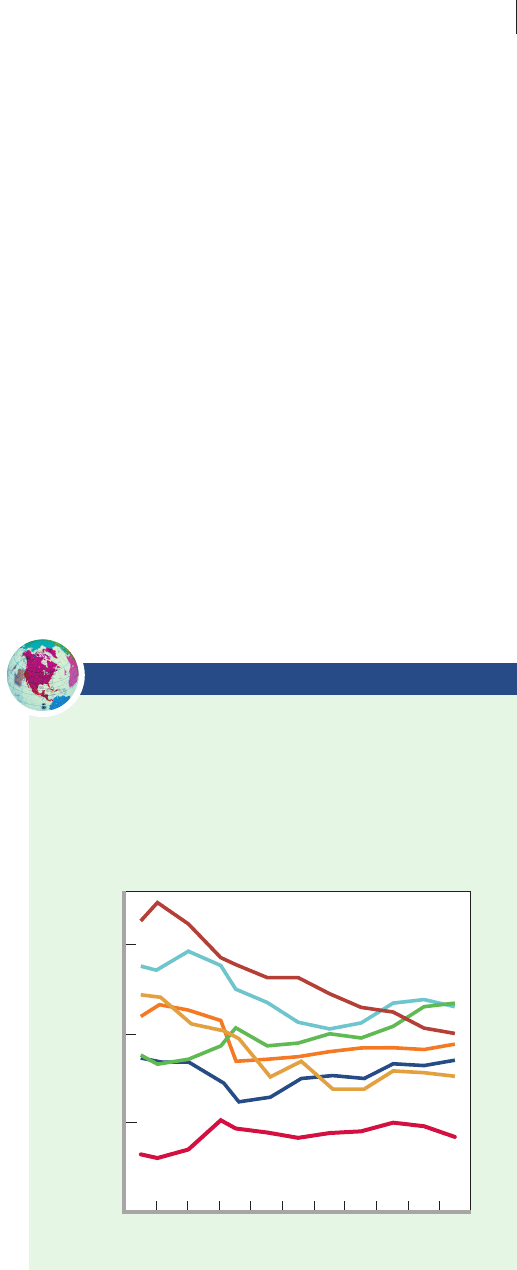

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE 15.1

15

10

5

Misery Index

Japan

20051995 1997 1999 2003

France

Germany

U.S.

U.K.

Italy

Canada

2001

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, stats.bls.gov.

The Misery Index, Selected Nations, 1995–2005

The misery index adds together a nation’s unemployment rate

and its inflation rate to get a measure of national economic

discomfort. For example, a nation with a 5 percent rate of un-

employment and a 5 percent inflation rate would have a misery

index number of 10, as would a nation with an 8 percent un-

employment rate and a 2 percent inflation rate.

mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 293mcc26632_ch15_284-301.indd 293 9/1/06 3:17:10 PM9/1/06 3:17:10 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES