McConnell С., Campbell R. Macroeconomics: principles, problems, and policies, 17th ed

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PART FIVE

Long-Run Perspectives and Macroeconomic Debates

314

A caution: Those who champion the idea of a New

Economy emphasize that it does not mean that the busi-

ness cycle is dead. Indeed, the economy slowed in the first

two months of 2001 and receded over the following eight

months of that year. The New Economy is simply one for

which the trend lin es of productivity growth and economic

growth are steeper than they were in the preceding two

decades. Real output may periodically deviate below and

above the steeper trend lines.

Skepticism about Permanence

Although most macroeconomists have revised their fore-

casts for long-term productivity growth upward, at least

slightly, others are still skeptical and urge a “wait-and-see”

approach. Skeptics acknowledge that the economy has ex-

perienced a rapid advance of new technology, some new

firms have experienced increasing returns, and global

competition has increased. But they wonder if these fac-

tors are sufficiently profound to produce a 15- to 20-year

period of substantially higher rates of productivity growth

and real GDP growth.

Skeptics point out that productivity surged between

1975 and 1978 and between 1983 and 1986 but in each

case soon reverted to its lower long-run trend. The higher

trend line of productivity inferred from the short-run

spurt of productivity could prove to be transient. Only by

looking backward over long periods can economists dis-

tinguish the start of a new long-run secular trend from a

shorter-term boost in productivity related to the business

cycle and temporary factors.

What Can We Conclude?

Given the different views on the New Economy, what should

we conclude? Perhaps the safest conclusions are these:

• The prospects for a continued long-run rapid trend

of productivity growth are good (see Global Per-

spective 16.2). Studies indicate that productivity ad-

vance related to information technology has spread

to a wide range of industries, including services.

Even in the recession year 2001 and in 2002, when

the economy was sluggish, productivity growth re-

mained strong. Specifically, it averaged about 3.3

percent in the business sector over those two years.

It rose by 4.1 percent in 2003, 3.5 percent in 2004,

and 2.7 percent in 2005, as the economy vigorously

expanded.

• Time will tell. Several more years must elapse before

economists can declare the recent productivity

acceleration a long-run, sustainable trend. (Key

Question 9)

QUICK REVIEW 16.3

• Over long time periods, labor productivity growth

determines an economy’s growth of real wages and its

standard of living.

• Many economists believe that the United States has entered

a period of faster productivity growth and higher rates of

economic growth.

• The productivity acceleration is based on rapid technological

change in the form of the microchip and information

technology, increasing returns and lower per-unit costs, and

heightened global competition that helps hold down prices.

• Faster productivity growth means the economy has a higher

“economic speed limit”: It can grow more rapidly than

previously without producing inflation. Nonetheless, many

economists caution that it is still too early to determine

whether the higher rates of productivity are a lasting long-

run trend or a fortunate short-lived occurrence.

Is Growth Desirable and

Sustainable?

Economists usually take for granted that economic growth

is desirable and sustainable. But not everyone agrees.

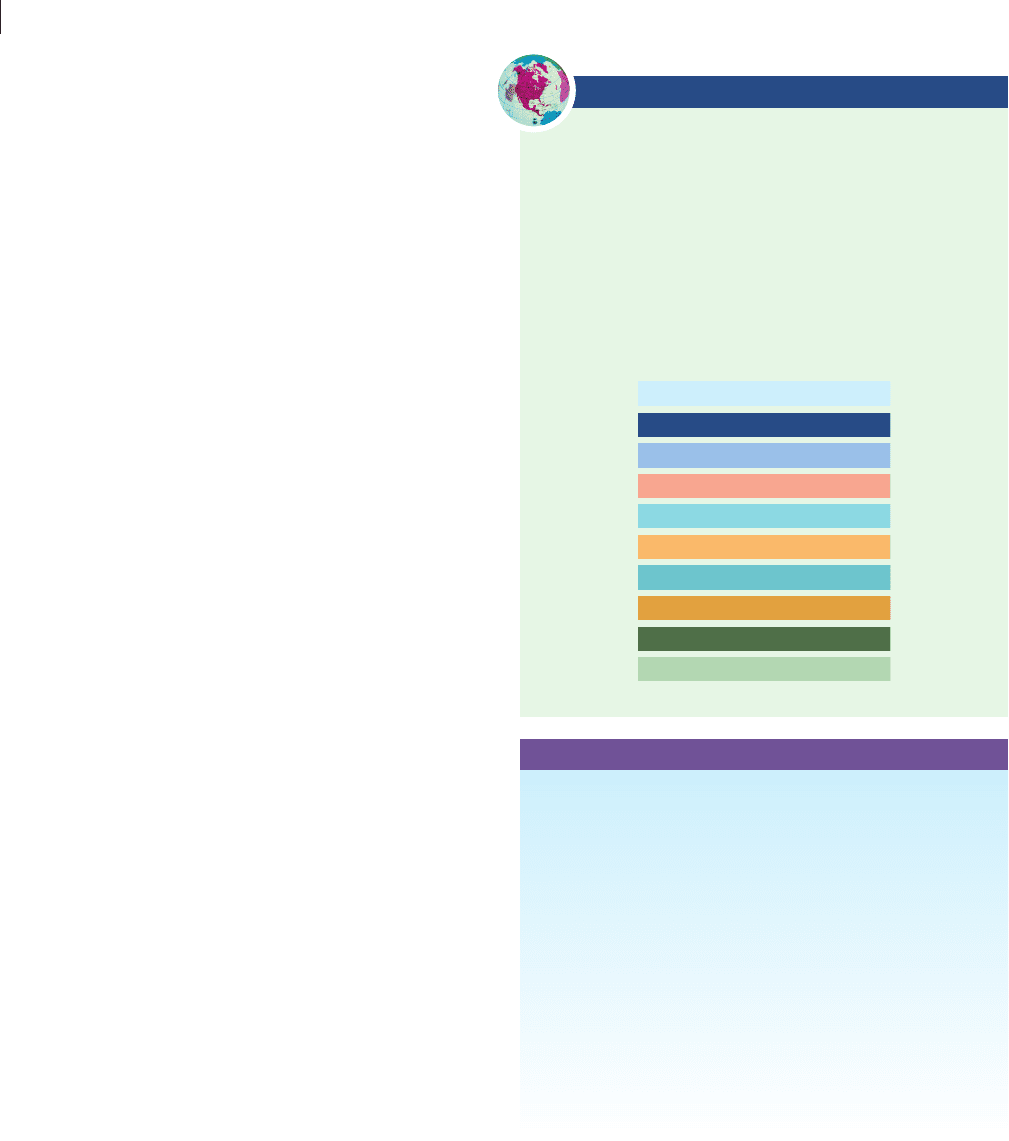

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE 16.2

Source: World Economic Forum, www.weforum.org/.

Growth Competitiveness Index

The World Economic Forum annually compiles a growth com-

petitiveness index, which uses various factors (such as innova-

tiveness, effective transfer of technology among sectors,

efficiency of the financial system, rates of investment, and de-

gree of integration with the rest of the world) to measure the

ability of a country to achieve economic growth over time.

Here is its top 10 list for 2005.

Growth

Competitiveness

Ranking, 2005

Country

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Finland

United States

Sweden

Denmark

Taiwan

Singapore

Iceland

Switzerland

Norway

Australia

mcc26632_ch16_302-319.indd 314mcc26632_ch16_302-319.indd 314 9/1/06 3:45:29 PM9/1/06 3:45:29 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 16

Economic Growth

315

The Antigrowth View

Critics of growth say industrialization and growth result

in pollution, global warming, ozone depletion, and other

environmental problems. These adverse negative exter-

nalities occur because inputs in the production process re-

enter the environment as some form of waste. The more

rapid our growth and the higher our standard of living,

the more waste the environment must absorb—or attempt

to absorb. In an already wealthy society, further growth

usually means satisfying increasingly trivial wants at the

cost of mounting threats to the ecological system.

Critics of growth also argue that there is little com-

pelling evidence that economic growth has solved socio-

logical problems such as poverty, homelessness, and

discrimination. Consider poverty: In the antigrowth view,

American poverty is a problem of distribution, not pro-

duction. The requisite for solving the problem is commit-

ment and political courage to redistribute wealth and

income, not further increases in output.

Antigrowth sentiment also says that while growth may

permit us to “make a better living,” it does not give us

“the good life.” We may be producing more and enjoying

it less. Growth means frantic paces on jobs, worker

burnout, and alienated employees who have little or no

control over decisions affecting their lives. The changing

technology at the core of growth poses new anxieties and

new sources of insecurity for workers. Both high-level and

low-level workers face the prospect of having their hard-

earned skills and experience rendered obsolete by an

onrushing technology. High-growth economies are high-

stress economies, which may impair our physical and

mental health.

Finally, critics of high rates of growth doubt that they

are sustainable. The planet Earth has finite amounts of

natural resources available, and they are being consumed

at alarming rates. Higher rates of economic growth sim-

ply speed up the degradation and exhaustion of the earth’s

resources. In this view, slower economic growth that is

environmentally sustainable is preferable to faster

growth.

In Defense of Economic Growth

The primary defense of growth is that it is the path to the

greater material abundance and higher living standards

desired by the vast majority of people. Rising output and

incomes allow people to buy

more education, recreation, and travel, more medical care,

closer communications, more skilled personal and profes-

sional services, and better-designed as well as more numerous

products. It also means more art, music, and poetry, theater,

and drama. It can even mean more time and resources de-

voted to spiritual growth and human development.

1

Growth also enables society to improve the nation’s in-

frastructure, enhance the care of the sick and elderly, pro-

vide greater access for the disabled, and provide more police

and fire protection. Economic growth may be the only real-

istic way to reduce poverty, since there is little political sup-

port for greater redistribution of income. The way to

improve the economic position of the poor is to increase

household incomes through higher productivity and eco-

nomic growth. Also, a no-growth policy among industrial

nations might severely limit growth in poor nations. For-

eign investment and development assistance in those nations

would fall, keeping the world’s poor in poverty longer.

Economic growth has not made labor more unpleas-

ant or hazardous, as critics suggest. New machinery is

usually less taxing and less dangerous than the machinery

it replaces. Air-conditioned workplaces are more pleasant

than steamy workshops. Furthermore, why would an end

to economic growth reduce materialism or alienation?

The loudest protests against materialism are heard in

those nations and groups that now enjoy the highest levels

of material abundance! The high standard of living that

growth provides has increased our leisure and given us

more time for reflection and self-fulfillment.

Does growth threaten the environment? The connec-

tion between growth and environment is tenuous, say

growth proponents. Increases in economic growth need

not mean increases in pollution. Pollution is not so much a

by-product of growth as it is a “problem of the commons.”

Much of the environment—streams, lakes, oceans, and the

air—is treated as common property, with no or insufficient

restrictions on its use. The commons have become our

dumping grounds; we have overused and debased them.

Environmental pollution is a case of negative externalities,

and correcting this problem involves regulatory legislation,

specific taxes (“effluent charges”), or market-based incen-

tives to remedy misuse of the environment.

Those who support growth admit there are serious

environmental problems. But they say that limiting growth

is the wrong solution. Growth has allowed economies to

reduce pollution, be more sensitive to environmental

considerations, set aside wilderness, create national parks

and monuments, and clean up hazardous waste, while still

enabling rising household incomes.

Is growth sustainable? Yes, say the proponents of

growth. If we were depleting natural resources faster

1

Alice M. Rivlin, Reviving the American Dream (Washington, D.C.:

Brookings Institution, 1992), p. 36.

mcc26632_ch16_302-319.indd 315mcc26632_ch16_302-319.indd 315 9/1/06 3:45:29 PM9/1/06 3:45:29 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART FIVE

Long-Run Perspectives and Macroeconomic Debates

316

Last

Word

Economic Growth in China

China’s economic growth rate in the past 25 years is

among the highest recorded for any country during

any period of world history.

Propelled by capitalistic reforms, China has experienced nearly

9 percent annual growth rates over the past 25 years. Real out-

put has more than quadrupled over that period. In 2004, China’s

growth rate was 10.1 percent and in 2005 it was 9.8 percent.

Expanded output and income have boosted domestic saving and

investment, and the growth of capital goods has further in-

creased productivity, output, and income. The rising income,

together with inexpensive labor, has attracted more direct for-

eign investment (a total of $150 billion between 2003 and 2005).

China’s real GDP and real income have grown much more

rapidly than China’s population.

Per capita income has increased

at a high annual rate of 8 per-

cent since 1980. This is particu-

larly noteworthy because

China’s population has ex-

panded by 14 million a year

(despite a policy which encour-

ages one child per family).

Based on exchange rates,

China’s per capita income is

now about $1390 annually. But

because the prices of many ba-

sic items in China are still low

and are not totally reflected in

exchange rates, Chinese per capita purchasing power is estimated

to be equivalent to $6300 of income in the United States.

The growth of per capita income in China has resulted from

increased use of capital, improved technology, and shifts of labor

away from lower-productivity toward higher-productivity uses.

One such shift of employment has been from agriculture toward

rural and urban manufacturing. Another shift has been from state-

owned enterprises toward private firms. Both shifts have raised the

productivity of Chinese workers.

Chinese economic growth had been accompanied by a

huge expansion of China’s international trade. Chinese exports

rose from $5 billion in 1978 to $752 billion in 2005. These exports

have provided the foreign currency needed to import consumer

goods and capital goods. Imports of capital goods from industrially

advanced countries have brought with them highly advanced tech-

nology that is embodied in, for example, factory design, industrial

machinery, office equipment, and telecommunications systems.

China still faces some significant problems in its transition

to the market system, however. At times, investment booms in

China have resulted in too much spending relative to production

capacity. The result has been some periods of 15 to 25 percent

annual rates of inflation. China has successfully confronted the

inflation problem by giving its central bank more power so that,

when appropriate, the bank can raise interest rates to damp down

investment spending. This greater monetary control has reduced

inflation significantly. China’s inflation rate was a mild 1.2 per-

cent in 2003, 4.1 percent in 2004, and 1.9 percent in 2005.

Nevertheless, the overall financial system in China remains

weak and inadequate. Many unprofitable state-owned enter-

prises owe colossal sums of money on loans made by the Chi-

nese state-owned banks (an estimate is nearly $100 billion).

Because most of these loans are not collectible, the government

may need to bail out the banks to keep them in operation.

Unemployment is also a

problem. Even though the tran-

sition from an agriculture-domi-

nated economy to a more urban,

industrial economy has been

gradual, considerable displace-

ment of labor has occurred.

There is substantial unemploy-

ment and underemployment in

the interior regions of China.

China still has much work

to do to integrate its economy

fully into the world’s system of

international finance and trade.

As a condition of joining the

World Trade Organization in

2001, China agreed to reduce its high tariffs on imports and re-

move restrictions on foreign ownership. In addition, it agreed to

change its poor record of protecting intellectual property rights

such as copyrights, trademarks, and patents. Unauthorized

copying of products is a major source of trade friction between

China and the United States. So, too, is the artificially low in-

ternational value of China’s currency, which has contributed to a

$200 billion annual trade surplus with the United States.

China’s economic development has been very uneven geo-

graphically. Hong Kong is a wealthy capitalist city with per capita

income of about $24,000. The standard of living is also relatively

high in China’s southern provinces and coastal cities, although

not nearly as high as it is in Hong Kong. In fact, people living in

these special economic zones have been the major beneficiaries of

China’s rapid growth. In contrast, the majority of people living

elsewhere in China have very low incomes. Despite its remark-

able recent economic successes, China remains a relatively low-

income nation. But that status is quickly changing.

316

mcc26632_ch16_302-319.indd 316mcc26632_ch16_302-319.indd 316 9/1/06 3:45:30 PM9/1/06 3:45:30 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 16

Economic Growth

317

than their discovery, we would see the prices of those

resources rise. That has not been the case for most natu-

ral resources; in fact, the prices of most of them have

declined. And if one natural resource becomes too ex-

pensive, another resource will be substituted for it.

Moreover, say economists, economic growth has to do

with the expansion and application of human knowledge

and information, not of extractable natural resources. In

this view, economic growth is limited only by human

imagination.

Summary

1. Economic growth—measured as either an increase in real

output or an increase in real output per capita—increases

material abundance and raises a nation’s standard of living.

2. The supply factors in economic growth are (a) the quantity

and quality of a nation’s natural resources, (b) the quantity

and quality of its human resources, (c) its stock of capital fa-

cilities, and (d) its technology. Two other factors—a suffi-

cient level of aggregate demand and economic efficiency—are

necessary for the economy to realize its growth potential.

3. The growth of production capacity is shown graphically as

an outward shift of a nation’s production possibilities curve

or as a rightward shift of its long-run aggregate supply

curve. Growth is realized when total spending rises suffi-

ciently to match the growth of production capacity.

4. Between 1950 and 2005 the annual growth rate of real GDP

for the United States averaged about 3.5 percent; the annual

growth rate of real GDP per capita was about 2.3 percent.

5. U.S. real GDP has grown partly because of increased inputs

of labor and primarily because of increases in the productiv-

ity of labor. The increases in productivity have resulted

mainly from technological progress, increases in the quantity

of capital per worker, improvements in the quality of labor,

economies of scale, and an improved allocation of labor.

6. Over long time periods, the growth of labor productivity

underlies an economy’s growth of real wages and its stan-

dard of living.

7. Productivity rose by 2.9 percent annually between 1995 and

2005, compared to 1.4 percent annually between 1973 and

1995. Some economists think this productivity acceleration

will be long-lasting and is reflective of a New Economy—

one of faster productivity growth and greater noninflation-

ary economic growth.

8. The New Economy is based on (a) rapid technological

change in the form of the microchip and information tech-

nology, (b) increasing returns and lower per-unit costs, and

(c) heightened global competition that holds down prices.

9. The main sources of increasing returns in recent years are

(a) use of more specialized inputs as firms grow, (b) the

spreading of development costs, (c) simultaneous consump-

tion by consumers, (d) network effects, and (e) learning by

doing. Increasing returns mean higher productivity and

lower per-unit production costs.

10. Skeptics wonder if the recent productivity acceleration is

permanent, and suggest a wait-and-see approach. They

point out that surges in productivity and real GDP growth

have previously occurred during vigorous economic expan-

sions but do not necessarily represent long-lived trends.

11. Critics of rapid growth say that it adds to environmental

degradation, increases human stress, and exhausts the earth’s

finite supply of natural resources. Defenders of rapid growth

say that it is the primary path to the rising living standards

nearly universally desired by people, that it need not debase

the environment, and that there are no indications that we

are running out of resources. Growth is based on the expan-

sion and application of human knowledge, which is limited

only by human imagination.

Terms and Concepts

economic growth

supply factors

demand factor

efficiency factor

labor productivity

labor-force participation rate

growth accounting

infrastructure

human capital

economies of scale

New Economy

information technology

start-up firms

increasing returns

network effects

learning by doing

mcc26632_ch16_302-319.indd 317mcc26632_ch16_302-319.indd 317 9/1/06 3:45:30 PM9/1/06 3:45:30 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

PART FIVE

Long-Run Perspectives and Macroeconomic Debates

318

Study Questions

1. KEY QUESTION What are the four supply factors of eco-

nomic growth? What is the demand factor? What is the ef-

ficiency factor? Illustrate these factors in terms of the

production possibilities curve.

2. Suppose that Alpha and Omega have identically sized work-

ing-age populations but that annual hours of work are much

greater in Alpha than in Omega. Provide two possible ex-

planations.

3. Suppose that work hours in New Zombie are 200 in year 1

and productivity is $8. What is New Zombie’s real GDP? If

work hours increase to 210 in year 2 and productivity rises

to $10, what is New Zombie’s rate of economic growth?

4. What is the relationship between a nation’s production pos-

sibilities curve and its long-run aggregate supply curve?

How does each relate to the idea of a New Economy?

5.

KEY QUESTION Between 1990 and 2005 the U.S. price

level rose by about 50 percent while real output increased

by about 56 percent. Use the aggregate demand–aggregate

supply model to illustrate these outcomes graphically.

6.

KEY QUESTION To what extent have increases in U.S. real

GDP resulted from more labor inputs? From higher labor

productivity? Rearrange the following contributors to the

growth of productivity in order of their quantitative im-

portance: economies of scale, quantity of capital, improved

resource allocation, education and training, technological

advance.

7. True or false? If false, explain why.

a. Technological advance, which to date has played a rela-

tively small role in U.S. economic growth, is destined to

play a more important role in the future.

b. Many public capital goods are complementary to private

capital goods.

c. Immigration has slowed economic growth in the United

States.

8. Explain why there is such a close relationship between

changes in a nation’s rate of productivity growth and changes

in its average real hourly wage.

9.

KEY QUESTION Relate each of the following to the New

Economy:

a. The rate of productivity growth

b. Information technology

c. Increasing returns

d. Network effects

e. Global competition

10. Provide three examples of products or services that can be

simultaneously consumed by many people. Explain why la-

bor productivity greatly rises as the firm sells more units of

the product or service. Explain why the higher level of sales

greatly reduces the per-unit cost of the product.

11. What is meant when economists say that the U.S. economy

has “a higher safe speed limit” than it had previously? If the

New Economy has a higher safe speed limit, what explains

the series of interest-rate hikes engineered by the Federal

Reserve in 2004 and 2005.

12. Productivity often rises during economic expansions and falls

during economic recessions. Can you think of reasons why?

Briefly explain. (Hint: Remember that the level of productiv-

ity involves both levels of output and levels of labor input.)

13.

LAST WORD Based on the information in this chapter, con-

trast the economic growth rates of the United States and

China over the last 25 years. How does the real GDP per

capita of China compare with that of the United States?

Why is there such a huge disparity of per capita income be-

tween China’s coastal cities and its interior regions?

Web-Based Questions

1. U.S. ECONOMIC GROWTH—WHAT ARE THE LATEST

RATES? Go to the Bureau of Economic Analysis Web site,

www.bea.gov , and use the data interactivity feature to find

National Income and Product Account Table 1.1. What are

the quarterly growth rates (annualized) for the U.S. econ-

omy for the last six quarters? Is the average of those rates

above or below the long-run U.S. annual growth rate of

3.5 percent? Expand the range of years, if necessary, to find

the last time real GDP declined in two or more successive

quarters. What were those quarters?

2.

WHAT’S UP WITH PRODUCTIVITY? Visit the Bureau of

Labor Statistics Web site, www.bls.gov . In sequence, select

Productivity and Costs, Get Detailed Statistics, and

Most Requested Statistics to find quarterly growth rates

(annualized) for business output per hour for the last six

quarters. Is the average of those rates higher or lower than

the 1.4 percent average annual growth rate of productivity

during the 1973–1995 period?

3.

PRODUCTIVITY AND TECHNOLOGY—EXAMPLES OF

INNOVATIONS IN COMPUTERS AND COMMUNICATIONS

Recent innovations in computers and communications tech-

nologies are increasing productivity. Lucent Technologies

(formerly Bell Labs), at www.lucent.com/minds/discoveries ,

provides a timeline of company innovations over the past

80 years. Cite five technological “home runs” (for example,

the transistor in 1947) and five technological “singles” (for

example, free space optical switching in 1990). Which single

innovation do you think has increased productivity the

most? List two innovations since 1990. How might they

boost productivity?

mcc26632_ch16_302-319.indd 318mcc26632_ch16_302-319.indd 318 9/1/06 3:45:31 PM9/1/06 3:45:31 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

16

WEB

Bonus Web Chapterwww.mcconnell17.com

The Economics of

Developing Countries

Chapter 16 Web is a bonus chapter found at the book’s Web site, www.mcconnell17.com. It ex-

tends the analysis of Part 5, “Long-Run Perspectives and Macroeconomic Dabates,” and may or may

not be assigned by your instructor.

CHAPTER 16W CONTENTS

The Rich and the Poor

Classifications / Comparisons / Growth, Decline, and Income

Gaps / The Human Realities of Poverty

Obstacles to Economic Development

Natural Resources / Human Resources / Capital

Accumulation / Technological Advance / Sociocultural and

Institutional Factors

The Vicious Circle

The Role of Government

A Positive Role / Public Sector Problems

Role of Advanced Nations

Expanding Trade / Foreign Aid: Public Loans and Grants / Flows

of Private Capital

Where from Here?

DVC Policies for Promoting Growth / IAC Policies for Fostering

DVC Growth

Last Word: Famine in Africa

mcc26632_ch16_302-319.indd 319mcc26632_ch16_302-319.indd 319 9/1/06 3:45:31 PM9/1/06 3:45:31 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

16

WEB

Bonus Web Chapterwww.mcconnell17.com

The Economics of Developing

Countries

It is difficult for those of us in the United States, where per capita GDP in 2005 was about $42,000,

to grasp the fact that about 2.7 billion people, or nearly half the world population, live on $2 or less a

day. And about 1.1 billion live on less than $1 a day. Hunger, squalor, and disease are the norm in many

nations of the world.

In this bonus Web chapter we identify the developing countries, discuss their characteristics, and

explore the obstacles that have impeded their growth. We also examine the appropriate roles of the

private sector and government in economic development. Finally, we look at policies that might help

developing countries increase their growth rates.

IN THIS CHAPTER YOU WILL LEARN:

• How the World Bank distinguishes between

industrial advanced countries (high-income

nations) and developing countries (middle-income

and low-income nations).

• Some of the obstacles to economic development.

• About the vicious circle of poverty that afflicts low-

income nations.

• The role of government in promoting economic

development within low-income nations.

• How industrial nations attempt to aid low-income

countries.

mcc26632_ch16w.indd 1mcc26632_ch16w.indd 1 10/4/06 7:22:36 PM10/4/06 7:22:36 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 16W

The Economics of Developing Countries

16W-2

The Rich and the Poor

Just as there is considerable income inequality among

families within a nation, so too is there great income

inequality among the family of nations. According to the

United Nations, the richest 20 percent of the world’s pop-

ulation receives more than 80 percent of the world’s in-

come; the poorest 20 percent receives less than 2 percent.

The poorest 60 percent receives less than 6 percent of the

world’s income.

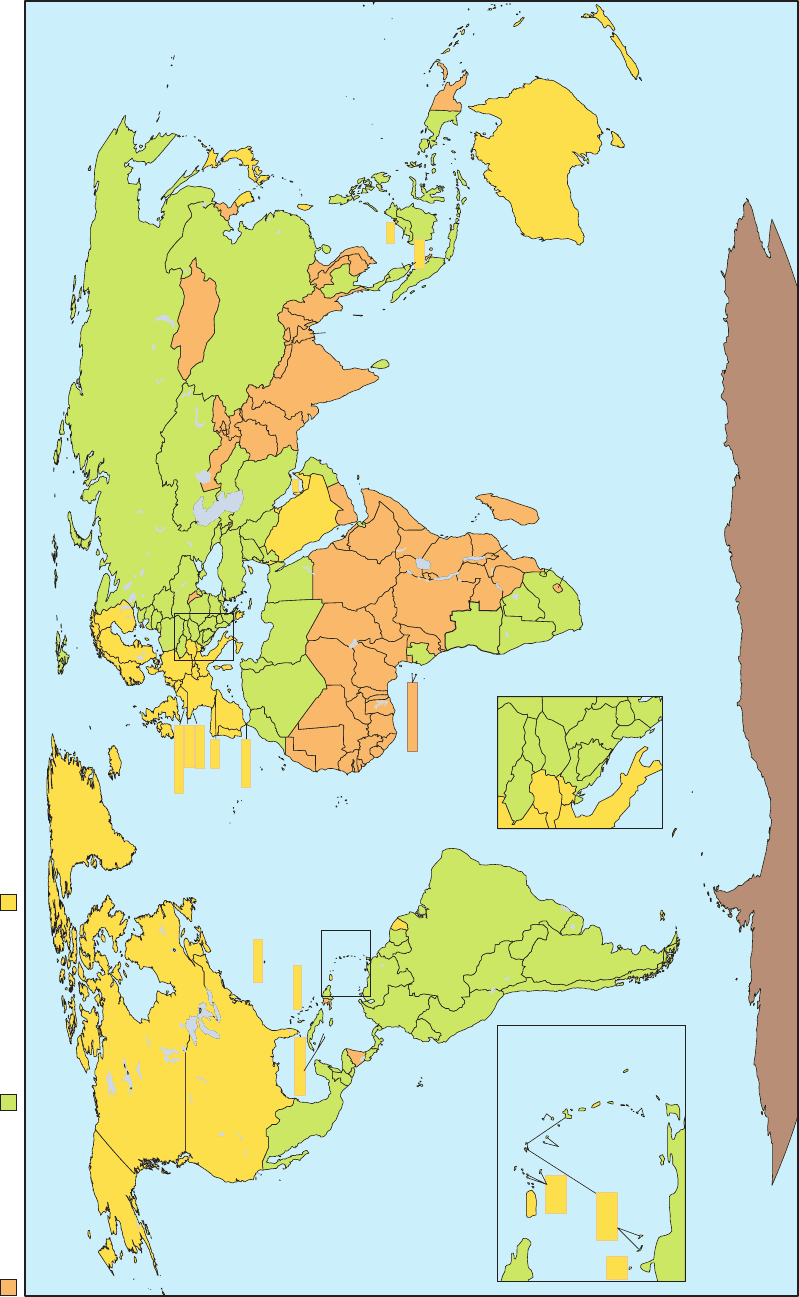

Classifications

The World Bank classifies countries into high-income,

medium-income, and low-income countries on the basis

of national income per capita, as shown in Figure 16W.1 .

The high-income nations, shown in gold, are known as the

industrially advanced countries (IACs) ; they include

the United States, Japan, Canada, Australia, New Zealand,

and most of the nations of western Europe. In general,

these nations have well-developed market economies

based on large stocks of capital goods, advanced produc-

tion technologies, and well-educated workers. In 2004

these economies had a per capita income of $32,040.

The remaining nations of the world are called devel-

oping countries (DVCs) . They have wide variations of

income per capita and are mainly located in Africa, Asia,

and Latin America. The DVCs are a diverse group that

can be subdivided into two groups:

• The middle-income nations, shown in green in Figure

16W.1 , include such countries as Brazil, Iran, Poland,

Russia, South Africa, and Thailand. Per capita output

of these middle-income nations ranged from $826 to

$10,065 in 2004 and averaged $2190.

• The low-income nations, shown in orange, had a per

capita income of $825 or less in 2004 and averaged

only $510 of income per person. India, Indonesia,

and the sub-Saharan nations of Africa dominate this

group. These DVCs have relatively low levels of in-

dustrialization. In general, literacy rates are low, un-

employment is high, population growth is rapid, and

exports consist largely of agricultural produce (such

as cocoa, bananas, sugar, raw cotton) and raw materi-

als (such as copper, iron ore, natural rubber). Capital

equipment is minimal, production technologies are

simple, and labor productivity is very low. About

37 percent of the world’s population lives in these

low-income DVCs, all of which suffer widespread

poverty.

Comparisons

Several comparisons will bring the differences in world in-

come into sharper focus:

• In 2004 U.S. GDP was nearly $12 trillion; the com-

bined GDPs of the DVCs in that year came to only

$5.5 trillion.

• The United States, with only 5 percent of the

world’s population, produces 31 percent of the

world’s output.

• Per capita GDP of the United States is 207 times

greater than per capita GDP in Sierra Leone, one of

the world’s poorest nations.

• The annual sales of the world’s largest corporations

exceed the GDPs of many of the DVCs. Wal-Mart’s

annual world revenues are greater than the GDPs of

all but 19 nations.

Growth, Decline, and

Income Gaps

Two other points relating to the nations shown in Figure

16W.1 should be noted. First, the various nations have

demonstrated considerable differences in their ability to

improve circumstances over time. On the one hand, DVCs

such as China, Malaysia, Chile, and Thailand achieved

high annual growth rates in their GDPs in recent decades.

Consequently, their real output per capita increased sev-

eral fold. Several former DVCs, such as Singapore,

Greece, and Hong Kong (now part of China), have

achieved IAC status. In contrast, a number of DVCs in

sub-Saharan Africa have recently been experiencing de-

clining per capita GDPs.

Second, the absolute income gap between rich and poor

nations has been widening. Suppose the per capita incomes

of the advanced and developing countries were growing at

about 2 percent per year. Because the income base in the

advanced countries is initially much higher, the absolute in-

come gap grows. If per capita income is $400 a year in a

DVC, a 2 percent growth rate means an $8 increase in in-

come. Where per capita income is $20,000 per year in an

IAC, the same 2 percent growth rate translates into a $400

increase in income. Thus the absolute income gap will have

increased from $19,600 (⫽ $20,000 ⫺ $400) to $19,992

(⫽ $20,400 ⫺ $408). The DVCs must grow faster than the

IACs for the gap to be narrowed. (Key Question 3)

The Human Realities of Poverty

Development economist Michael Todaro points out that

mere statistics conceal the human implications of the ex-

treme poverty in the low-income DVCs:

Let us examine a typical “extended” family in rural Asia. The

Asian household is likely to comprise ten or more people,

including parents, five to seven children, two grandparents,

mcc26632_ch16w.indd 2mcc26632_ch16w.indd 2 10/4/06 7:22:39 PM10/4/06 7:22:39 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

FIGURE 16W.1 Groups of economies. The world’s nations are grouped into industrially advanced countries (IACs) and developing countries (DVCs). The IACs (shown in gold) are high-income

countries. The DVCs are middle-income and low-income countries (shown respectively in green and in orange).

Austria

Italy

Germany

Hungary

Romania

Bulgaria

Poland

Ukraine

Czech Republic

Slovak Republic

Greece

Albania

Serbia

and

Montenegro

Bosnia

Croatia

Slovenia

Macedonia

Venezuela

Dominican

Republic

Trinidad

and Tobago

Martinique (Fr)

Guadeloupe (Fr)

St. Lucia

Dominica

St. Kitts

and Nevis

Antigua and Barbuda

St. Vincent and

the Grenadines

Barbados

Grenada

Puerto Rico

(US)

U.S. Virgin

Islands (US)

Netherlands

Antilles (Neth.)

Aruba

(Neth.)

Australia

Russian Federation

Finland

Italy

Spain

Sweden

Norway

Germany

France

Portugal

Romania

Bulgaria

Turkey

Denmark

Poland

Belarus

Ukraine

Greece

Cyprus

Neth.

Belgium

Ireland

Moldova

Lithuania

Latvia

Estonia

Luxembourg

Channel Islands (UK)

Switz.

Greenland

(Den)

Iceland

United States

Canada

Low-income economies Middle-income economies High-income economies

Mexico

The Bahamas

Bermuda (UK)

Cayman Islands (UK)

Cuba

Panama

El Salvador

Guatemala

Belize

Honduras

Nicaragua

Costa Rica

Jamaica

Haiti

Argentina

Bolivia

Colombia

Venezuela

Peru

Brazil

French Guiana (Fr)

Suriname

Guyana

Chile

Ecuador

Paraguay

Uruguay

Antarctica

Kenya

Ethiopia

Eritrea

Sudan

Egypt

Niger

Mauritania

Mali

Nigeria

Somalia

Namibia

Libya

Chad

South Africa

Tanzania

Zaire

Angola

Algeria

Madagascar

Mozambique

Botswana

Zambia

Gabon

Central African

Republic

Tunisia

Morocco

Uganda

Swaziland

Lesotho

Malawi

Burundi

Rwanda

Togo

Benin

Ghana

Ivory

Coast

Liberia

Sierra Leone

Guinea

Burkina

Gambia

Cameroon

Sao Tome & Principe

Zimbabwe

Congo

Equatorial Guinea

Western

Sahara

Djibouti

Senegal

Guinea Bissau

Canary Islands

Jordan

Israel

Lebanon

Armenia

Azerbaijan

Georgia

Kyrgyzstan

Tajikistan

Kuwait

Qatar

U.A.E.

Yemen

Syria

Iraq

Iran

Oman

Saudi Arabia

Afghanistan

Pakistan

India

China

Kazakhstan

Turkmenistan

Uzbekistan

Myanmar

Thailand

Cambodia

Nepal

Bhutan

Vietnam

Sri Lanka

Laos

Bangladesh

Malaysia

Papua

New Guinea

Brunei

Singapore

Philippines

Palau

Taiwan

Indonesia

Japan

Mongolia

South Korea

North Korea

New Zealand

U. K.

New Caledonia

Vanuatu

Liechtenstein

Gibralter (UK)

Andurra

Source: World Bank data, www.worldbank.com/ .

mcc26632_ch16w.indd 3mcc26632_ch16w.indd 3 10/4/06 7:22:39 PM10/4/06 7:22:39 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES

CHAPTER 16W

The Economics of Developing Countries

16W-4

and some aunts and uncles. They have a combined annual

income, both in money and in “kind” (i.e., they consume a

share of the food they grow), of $250 to $300. Together they

live in a poorly constructed one-room house as tenant farm-

ers on a large agricultural estate owned by an absentee land-

lord who lives in the nearby city. The father, mother, uncle,

and the older children must work all day on the land. None

of the adults can read or write; of the five school-age chil-

dren, only one attends school regularly; and he cannot ex-

pect to proceed beyond three or four years of primary

education. There is only one meal a day; it rarely changes

and it is rarely sufficient to alleviate the childrens’ constant

hunger pains. The house has no electricity, sanitation, or

fresh water supply. There is much sickness, but qualified

doctors and medical practitioners are far away in the cities

attending to the needs of wealthier families. The work is

hard, the sun is hot and aspirations for a better life are con-

stantly being snuffed out. In this part of the world the only

relief from the daily struggle for physical survival lies in the

spiritual traditions of the people.

1

Table 16W.1 contrasts various socioeconomic indica-

tors for selected DVCs with those for the United States

and Japan. These data confirm the major points stressed in

the quotation from Todaro.

Obstacles to Economic

Development

The paths to economic development are essentially the

same for developing countries as for the industrially ad-

vanced economies:

• The DVCs must use their existing supplies of re-

sources more efficiently. This means that they must

eliminate unemployment and underemployment and

also combine labor and capital resources in a way

that will achieve lowest-cost production. They must

also direct their scarce resources so that they will

achieve allocative efficiency.

• The DVCs must expand their available supplies of

resources. By achieving greater supplies of raw mate-

rials, capital equipment, and productive labor, and by

advancing its technological knowledge, a DVC can

push its production possibilities curve outward.

All DVCs are aware of these two paths to economic devel-

opment. Why, then, have some of them traveled those

paths while others have lagged far behind? The difference

lies in the physical, human, and socioeconomic environ-

ments of the various nations.

Natural Resources

No simple generalization is possible as to the role of natu-

ral resources in the economic development of DVCs be-

cause the distribution of natural resources among them is

so uneven. Some DVCs have valuable deposits of bauxite,

tin, copper, tungsten, nitrates, and petroleum and have

been able to use their natural resource endowments to

achieve rapid growth. The Organization of Petroleum Ex-

porting Countries (OPEC) is a standard example. In other

instances, natural resources are owned or controlled by

the multinational corporations of industrially advanced

countries, with the economic benefits from these resources

largely diverted abroad. Furthermore, world markets for

many of the farm products and raw materials that the

DVCs export are subject to large price fluctuations that

contribute to instability in their economies.

1

Michael P. Todaro, Economic Development in the Third World, 7th ed.

(New York: Addison Wesley Longman, 2000), p. 4.

TABLE 16W.1 Selected Socioeconomic Indicators of Development

(3) (4) (5) (6)

(1) (2) Under-5 Mortality Adult Personal Per Capita Energy

Per Capita Life Expectancy Rate per 1000, Illiteracy Rate, Computers per Consumption,

Country Income, 2004 at Birth, 2003 2003 Percent, 2004 1000, 2003 2002*

United States $41,400 77 years 8 1 658.9 7943

Japan 37,180 82 5 1 382.2 4058

Brazil 3090 69 35 12 74.8 1093

Mauritania 420 51 107 49 10.8 103

China 1290 71 37 9 27.6 960

India 620 63 87 39 7.2 513

Bangladesh 440 62 69

59 7.8 155

Ethiopia 110 42 169 58 2.2 297

Mozambique 250 41 147 54 4.5 436

*Kilograms of oil equivalent.

Source: World Development Indicators, 2005; World Development Report, 2006.

mcc26632_ch16w.indd 4mcc26632_ch16w.indd 4 10/4/06 7:22:40 PM10/4/06 7:22:40 PM

CONFIRMING PAGES