Mackesy P. The War for America, 1775-1783

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

page_2

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_2.html[1/17/2011 2:24:46 PM]

< previous page page_2 next page >

Page 2

Little had been done to meet the storm. A few regiments were ordered to Boston early in 1775 to reinforce the

garrison, and with them sailed three active Major-Generals to inject some vigour into Gage's irresolute command.

But Gage himself had been writing for many months that nothing short of an absolute reconquest of New England

could end the mischief, and it would need 20,000 men. The Cabinet was reluctant to face the truth. Aware of

England's diplomatic isolation, it hesitated to disperse its exiguous forces beyond the Atlantic; and, committed as

the Ministers were to a policy of financial retrenchment, they were reluctant to face the expense of placing the

army on a war establishment. Violence in the Boston area seemed to have been the work of a rabble without

leadership or spirit, and they clung to the hope that a small force used quickly would open the way to a political

solution. Gage was encouraged to try to disarm the provincials and protect British cargoes arriving in American

ports, even if it forced the Americans to take up arms prematurely.1 But of reinforcements only a dribble had been

sent: now three guardships and 600 marines; next a regiment of cavalry and three of foot. An addition to

regimental establishments was authorised early in 1775; but in May the Admiralty asked Parliament for fewer

seamen and less money than in the previous estimates. When Gage struck his blow at the rebel armaments, as he

had been ordered, the British government was still unprepared for a serious struggle.

On 29 May a rumour of war ran through Whitehall and St James's. There had been fighting between armed

Americans and a detachment of troops which was marching to seize the magazines at Concord. The rebels seemed

to have been bolder than might have been expected; but the report came from an American source, and might be

exaggerated. 'Be that however what it may', wrote an official in the American Department, 'the die is cast, and

more mischief will follow.'2 A decade of dispute had ended in bloodshed.

The despatch from Gage arrived a fortnight later, and confirmed the seriousness of the affair. As he had long since

warned the Ministry, the King's enemies were not a Boston rabble, but the farmers and freeholders of the country,3

and they had turned out in strength. Another couple of weeks went by before further news confirmed the scale of

the insurrection. The forts of Crown Point and Ticonderoga on the boundary between New England and Canada

had been surprised and captured with all their cannon and stores.

For the moment little could be done to strengthen Gage. Four more frigates were ordered to America to isolate

New England, and the Black Watch stood by to embark in Scotland. No further reinforcements could

1 Gage Corr., II, 1745, 17983.

2 Knox, 118.

3 Gage Corr., I, 374.

< previous page page_2 next page >

page_3

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_3.html[1/17/2011 2:24:47 PM]

< previous page page_3 next page >

Page 3

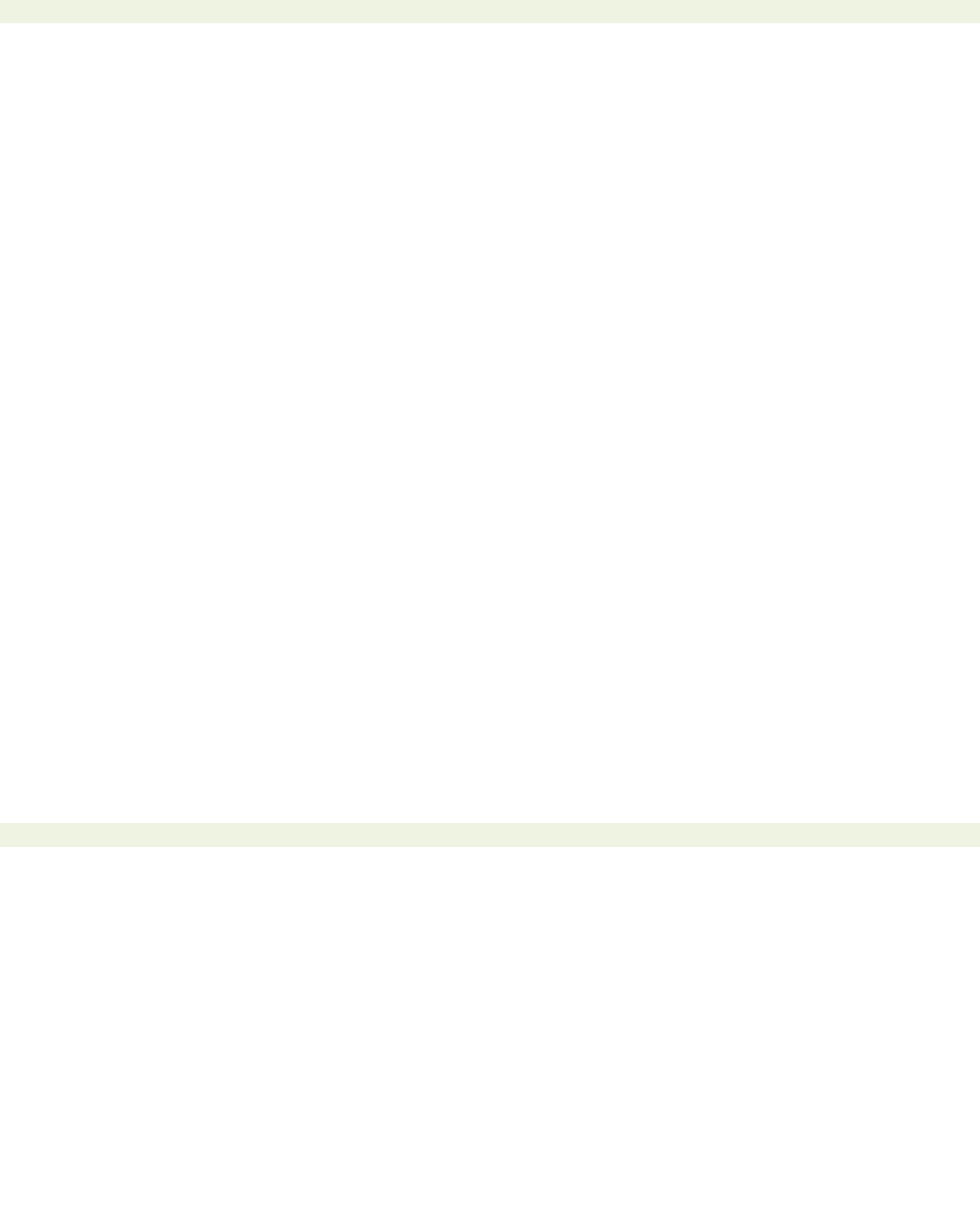

THE AMERICAN COLONIES, 1775

< previous page page_3 next page >

page_4

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_4.html[1/17/2011 2:24:48 PM]

< previous page page_4 next page >

Page 4

reach Boston from home during the present campaigning season; but seven battalions of infantry and a cavalry

regiment were on their way there, and the Ministers hoped to hear that Gage had broken out of the city and re-

opened his access to the countryside.1 The answer to their hopes was Bunker Hill.

Towards the end of June Gage had received his reinforcements, and resolved to dislodge the rebels from the

heights of Brede's Hill and Bunker Hill which commanded the town and upper harbour. The attack was launched

without reserves or any preparation for the wounded, in full confidence that it would achieve its object without

trouble. The works were stormed and the Americans forced to retreat; but in successive frontal assaults and bitter

fighting the British regiments were shattered. The soldiers' gallantry had cost them forty per cent of their strength.

The news of this Pyrrhic victory cast its shadow across Whitehall on 25 July, and it was clear beyond doubt that

New England was organised and determined. The Ministry had a foreign war on its hands.

2

A War of the Ancien Régime

The struggle which opened at Lexington was the last great war of the ancien régime. In the American War there

first appeared the fearful spectacle of a nation in arms; and the odium theologicum which had been banished from

warfare for a century returned to distress the nations. As a civil war in America the struggle was often characterised

by atrocious cruelty between rebels and loyalists; and even between the rebels and the British the conventions of

warfare sometimes threatened to break down. But the European participants kept hatred within bounds and

observed the rules. Indeed Englishmen in France fared better than in the Seven Years War, when Gibbon's dry

phrase recorded how the seizure of French shipping before the declaration had 'rendered that polite nation

somewhat peevish and difficult'. In the war for America civilised amenities were better preserved. In the summer

of Yorktown a tourist at Chepstow saw miles of iron waterpipes on the quay for shipment to Paris. French artists

were given passports to collect drawings for a book of travels; and on the other side of the Channel George Selwyn

could still export the Paris gossip and another Member of Parliament find refuge from his creditors. The Master-

General of the Irish Ordnance spent the autumn of 1778 in Provence for the sake of his health. Englishmen were

banned from French ports; but an influential woman was able to arrange matters for Henry Ellis, the explorer and

colonial governor, and he passed the first winter of the French war very agreeably in Marseilles society. So

1 Sandwich, I, 62; Gage Corr., II, 2002.

< previous page page_4 next page >

page_5

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_5.html[1/17/2011 2:24:48 PM]

< previous page page_5 next page >

Page 5

agreeably, that he had to retire to Spa and take the waters in the spring of 1779. There the French and English were

mixing freely; and if his own government had not inconveniently stopped the DoverCalais packet after being at war

with France for a year, he might have imagined that the whole world was at peace. Even the absurdities were

preserved. At New York Lord Carlisle used an insulting phrase about France, and was rewarded with a challenge

sent through the lines by Lafayette.1

The amenities were preserved because France and England were not divided by fanaticism. They were fighting

over quantitative issues of wealth and power. The stakes were high, and the danger grave. Yet the challenge was

limited. The belligerents looked to a future when they would live together and the balance of power once more be

called into play. They knew, moreover, that social stability transcended frontiers. A decade later the doctrines of

the French Revolution brought a new intensity to warfare, and since that time almost every major conflict has led

to revolution on the losing side. But in 1778 England faced no threat to her social or political structure, but only to

her power and wealth. Wraxall's Memoirs struck the note: 'No fears of subversion, extinction, and subjugation to

foreign violence, or to revolutionary arts, interrupted the general tranquillity of society.'

Limited objects called forth limited efforts. There are bounds to the sacrifices which people will make for material

and measurable ends, and neither the wealth nor the man-power of the warring nations could be fully deployed.

Governments might totter into bankruptcy, but they were bankrupt while their countries' wealth lay untapped.

Armies might be raised at a price, but there was no conscript population to provide a cheap reservoir of

replacements. Nor did the princes and oligarchies of Europe wish it otherwise. A whole nation could not be called

to arms without at least the illusion of political partnership; and the ruling classes of the eighteenth century had no

intention of paying the price of total war.

With no threat to their domination, the ruling classes of England had no challenge to throw off the sloth of old

ways. England was not forced to re-examine her political life, to remould her institutions and administration, or to

overhaul her war machine. The war of 1793 was to have a very different effect. The revolutionary challenge was to

unite the propertied classes, and lead to the overhaul of much antiquated machinery and habits. But the war for

America left the country politically divided. Patronage raged without check. In every sphere of government the old

ways which had served in the past continued. It was not that the country lacked vigour. The year of the

1 Torrington Diaries, 41; G 3321; I. R. Christie, The End of North's Ministry, 302; Carlisle, 374, 422;

Lothian, 339; Knox, 158.

< previous page page_5 next page >

page_6

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_6.html[1/17/2011 2:24:49 PM]

< previous page page_6 next page >

Page 6

American Declaration of Independence saw the first publication of three masterpieces. Adam Smith's The Wealth of

Nations pointed the way towards a new concept of imperial and commercial relations. Bentham's Fragment on

Government was a first devastating assault on the English constitution and the assumptions on which it rested inert.

And a friend of Lord North's, soon to accept a minor place in his administration, had been at work on the greatest

of historical apologias for a rational liberty: the first volume of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire burst on

the world in February 1776, as England gathered her forces for the counterstroke in America. David Hume lived to

congratulate Gibbon on his masterpiece, and died in Edinburgh three days after Howe's landing on Long Island.

The tragedy of administrative apathy was revealed in horror wherever soldiers and seamen were collected. The

troops of Revolutionary France were to be allowed to die because they could be replaced; the fighting men of

England in the last war of the old Europe were killed by neglect. Of scurvy in the navy we shall have more to say;

but a microcosm of the system and its effects on the army can be found in Jamaica. There the waste of life was

more than a tragedy: it threatened the island's safety. The Governor was convinced by experience that the fever

could be controlled by building barracks and hospitals and providing skilled doctors. He declared that the loss of

life bordered on murder: 'seven out of ten of the soldiers who perish in this country might be saved, if due attention

was paid to them when sick'. But the Jamaican Assembly would not bear the cost; and the government at home

would not take over the expense which it was the Jamaicans' interest and duty to bear.1

Nor was cruel neglect excused by financial stringency.2 Though country gentlemen disliked heavy taxation, they

had no means whatever of controlling expenditure in detail; and in spite of Pitt and Shelburne matters continued

much the same throughout the Napoleonic Wars. The Estimates and Extra Estimates voted by Parliament bore no

relation to requirements. The real 'extraordinary' expenditure required by changing circumstances was not

authorised by Parliament at all: it was met simply by running up departmental debts, and at the time of Yorktown

the interest-bearing Navy Debt was above £11 millions. The spending of the money was unchecked. The Treasury

did not control departmental spending; and Parliament, unable to limit expenditure in advance, was equally

impotent to audit it

1 CO 137/75, ff. 2001; CO 137/76, f. 144; CO 137/78, ff. 58, 135. The years are 177980, the Governor the

otherwise deplorable Dalling.

2 Naval finances are examined in R. G. Usher's unpublished thesis, Civil Administration of the British Navy

during the American Revolution, pp. 2030; the subject in general in J.E.D. Binney, British Public Finance and

Administration, 177492.

< previous page page_6 next page >

page_7

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_7.html[1/17/2011 2:24:49 PM]

< previous page page_7 next page >

Page 7

afterwards. Auditing meant merely the checking of arithmetic. There was no check on excessive spending, or on

the delivery of what had been paid for. Nor did the Admiralty attempt to use parliamentary grants for the purposes

for which they had been voted; and Lord Mulgrave, a Lord of the Admiralty, said this had been the practice since

the reign of James II.

Such as it was, the auditing was yet twenty years in arrears. The Paymaster-General treated the balance in his hands

as his own until his accounts were finally passed; and Henry Fox was still enjoying an income of £25,000 at his

death in 1774 from his unaudited balances, though he had resigned in 1765: four years later his executors paid in

£200,000. Lord North's Paymaster, Richard Rigby, handled his funds so freely that he was threatened with

impeachment. It seems a miracle that the machine continued to revolve. But as a Napoleonic general was to

observe,1 the corruption of English life in itself imposed certain bounds; 'and generally speaking the thefts are not

so scandalous as they would be elsewhere under the aegis of so convenient a legislation'.

3

'John Will Wallow in Preferment'

Long after the years of his great victories, Lord Chatham recalled that there had been no party politics at that time,

and that conversations between Ministers had been the most agreeable he could remember in his long experience.

His son was to enjoy a similar immunity from faction when he fought the French Revolution. It was not so in the

time of North.

The rancour of George III had driven into opposition the ablest men in politics: the aristocratic Rockingham group,

who numbered one in seven of the House of Commons and commanded in Burke, Sheridan and Fox a peerless

team of orators; and Chatham's odd and brilliant political heir Lord Shelburne, with about ten votes in the House.

The committed Opposition in 1780 numbered about a hundred in a House of five hundred and fifty-eight

members.2 Against them Lord North ranged a typical eighteenth-century coalition, bound together by the desire for

office: more stable than many, because it had the King's confidence and a leader who was a brilliant manager of

the House of Commons; yet the more bitterly assailed because its monopoly of power seemed so impregnable.

Lord North himself had one of the largest followings in the House, held together by their leader's position at the

Treasury. Lord Gower and Weymouth led the old Bedford group with about a dozen followers held together by

family and electoral interest. Lord Sandwich, once a member of the Bedfords, was by now the leader of his own

1 Foy, Peninsular War, I, 189.

2 The composition of the parties in 1780 is analysed by I. R. Christie, in his The End of North's Ministry, esp.

pp. 198 ff., 218 ff.

< previous page page_7 next page >

page_8

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_8.html[1/17/2011 2:24:50 PM]

< previous page page_8 next page >

Page 8

faction, based on the patronage which he controlled at the Admiralty and East India House. The survivors of the

old Grenville group were led by Lord Suffolk. With a scattering of other leaders controlling a vote or two, and the

steady support of the court and administration votes, Lord North could count on about 220 members in the House

of Commons.

The Ministry's majority of committed supporters did not guarantee a majority in a division. An absolute majority

of the House required another sixty votes; so that like all eighteenth-century governments it depended on the

goodwill of a body of independents. Conversely, the Opposition could succeed only by persuading enough

independents that the Ministers were leading them to disaster. Unlike many Oppositions of the century, the

Rockinghams had a programme to offer, which they developed during the course of the war: to end the American

War, and to break the power of the King's political patronage. But neither object commanded much support outside

the group. The attack on patronage could too easily be interpreted as a desperate expedient of self-interested men

who had once been happy to use the same royal influence for their own purposes. Still less was the American War

an effective issue, till its failure alienated the country. The Rockinghams were divided from the Shelburne group on

the question of peace terms, for the heirs of Chatham were not willing to surrender the sovereignty of America;

and from the country at large, or from the country gentlemen who represented it, by their attacks on the policy of

coercion. The spectacle of politicians avid for office crowing at the nation's disasters disgusted the ordinary

backbencher. 'The parricide joy of some at the losses of their country makes me mad', wrote a member after

Yorktown, though he was by no means an admirer of the Ministry. Nor, in spite of their intellectual brilliance, did

Charles Fox and his friends command confidence. 'Such farceurs as are in opposition, or such a desperate rantipole

vagabond as our Charles' were not likely to proselytise. The country had a long road to travel before the House

would vote Fox 'from a Pharo table to the head of the Exchequer'. Year after year Lord North held his own in his

lonely forensic battle against a battery of great orators. Through seven disastrous years of war he rode out the

storms, because there was no alternative Ministry to continue the struggle. Mediocre the Ministers might be,

unfortunate they certainly were; but their 'principles respecting America were agreeable to the people, and those of

Opposition offensive to them'.1

Nevertheless the Ministers' majority was often precarious. And in 1775, as the crisis in America approached, they

continued to give priority to the political game at home, and treated the American problem as an embarrassment to

be shed at the lowest cost. From this stemmed their reluctance to

1Life and Letters of Sir Gilbert Elliot, I, 74, 77; Carlisle, 553, 584.

< previous page page_8 next page >

page_9

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_9.html[1/17/2011 2:24:50 PM]

< previous page page_9 next page >

Page 9

strengthen the armed forces and increase expenditure. Even when the war was fairly launched, the government

continued in its political chains; chains which the Elder Pitt in his great Ministry had shaken off. Perhaps the most

pernicious of the pressures exerted by political weakness was on the appointment of generals and admirals.

Who were the wartime commanders? Most of the generals had been born in the seventeen-twenties, had grown up

in the era of Walpole and the Pelhams, and were around their fiftieth year when the war began; rather younger than

the admirals who were nearer sixty. Almost all were men of social rank and connection. The generals were sons of

peers, cousins and neighbours of dukes, school friends of earls. The admirals' backgrounds were more varied, for

the sons of peers and baronets were mixed with the sons of simple naval officers, and occasionally with lucky men

like Arbuthnot, of obscurer pedigree. Nevertheless the nobility predominated in the higher ranks of both services.

Lord Howe was an Irish peer, by the death of his elder brother at Ticonderoga. Keppel, Barrington and Byron were

sons of peers, Digby a grandson, Pye and Rodney related to the nobility. Drake, Hotham and Ross were sons of

baronets (the latter also a peer's grandson); Hyde Parker was the heir to a baronetcy.

Social ties clashed with military heirarchy. The aristocratic structure of the services affected their discipline.

Military subordination among officers may be strictest in an egalitarian society where no superiority but rank is

acknowledged. The violent quarrels between generals, admirals and governors which characterised the war might

have taken a more inhibited form in a society where social and military rank did not compete. Their chief cause, of

course, was the spoils system which still ruled supreme in every walk of life. Mere rank was not enough. As

courtiers sought places and the clergy rich livings, so a seaman hoped for a station or a ship to command, with a

share of prize money and the control of promotions; a soldier for the colonelcy of a regiment, the sinecure

governship of a fortress, or the perquisites of a command. Hard work and ability might help, but favour counted

most; and a seat in the House of Commons was an instrument for obtaining it. Lord Hardwicke had long ago

deplored the number of men of quality in the army as an obstacle to efficiency and a cloak for failure; and the

Elder Pitt had unsuccessfully promoted a bill to exclude junior officers of the two services from the House. The

twenty-three generals in the House in 1780, who included Howe, Clinton, Burgoyne, Cornwallis and Vaughan,

shared between them twenty-one colonelcies, nine governorships, and six or seven staff appointments. Any failure

which the Ministry dared to notice was likely to send the perpetrator into opposition.1

1 Namier, Structure of Politics . . ., 73; Whitworth, Ligonier, 194; Christie, 1789.

< previous page page_9 next page >

page_10

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_10.html[1/17/2011 2:24:51 PM]

< previous page page_10 next page >

Page 10

The system was as harmful to military efficiency as to the peace of the Ministry. The hunt for profitable places

might have placed the army at the mercy of politics had it not been for the royal family. Like his father, George III

took his military prerogative seriously. He at least, as Captain-General, was sufficiently above the crowd of

petitioners to defy their importunity. Where military and political considerations did not conflict, he was ready to

manipulate the army for the sake of the government's majority: for he regarded military sinecures as a fair prey.

But invariably he placed military interests above political calculations, and sheltered the army from the worst

effects of the spoils system. He resisted the raising of new regiments to confer rank on the Ministers' friends; and

when votes in the House were at issue his hand was light on the reins. Even the King's aides-de-camp could not be

relied on to vote with the government. Of the seven Generals in the House of Commons who voted with the

Opposition in 1780, only Burgoyne had no regiment, having lost it when he quarrelled with the Ministry after

Saratoga.1

In peacetime and in the absence of a Commander-in-Chief, the direct patronage of the army rested in the hands of

the Secretary at War, Lord Barrington; but when Amherst was made Commander-in-Chief on the outbreak of the

French war, Barrington relinquished the patronage to him. When Jenkinson, a Treasury man of business, succeeded

Barrington, he introduced a vigorous political supervision; but his powers were circumscribed. He could canvas

voters, and grant them leave at election-time; but in Amherst he found a drag on political action. 'Incapable of

doing a favour to his nearest connections', Amherst obstinately opposed political promotions. Jenkinson could only

refer applicants to him; and he in turn found shelter in the formula of 'putting names before his Majesty'.2

The system for naval appointments was more invidious. Naval patronage was not controlled by the sovereign or the

professional head of the service, but by the First Lord of the Admiralty, who was usually a leading politician.

During the American War faction and indiscipline were rife in the fleets; and Lord Sandwich, much hated by those

whose claims to employment he passed over, has been branded as the source of the trouble. His fortune was

rumoured to be below his station, which exposed him to damaging insinuations; and as the leader of a political

faction he had strong inducements to misuse his control of appointments. His power rested on the seventeen votes

1 Pares, George III and the Politicians, 19; Christie, 1789.

2 Add. MSS. 38306, ff. 136, 138, 149; Olive Anderson, 'Army and Parliamentary Management in the

American War' (J. Soc. Army Hist. Research, 1956, pp. 1469). Amherst's reference of applicants to the King's

will is habitual throughout his correspondence (WO 34/22641). For his opposition in later life to political

promotions, see Clode, Military Forces of the Crown, II, 94.

< previous page page_10 next page >

page_11

file:///C:/Users/User/AppData/Local/Temp/Rar$EX01.335/The%20War%20for%20America%20%201775-1783/files/page_11.html[1/17/2011 2:24:51 PM]

< previous page page_11 next page >

Page 11

which he controlled in the House of Commons, a private empire of patronage which made him formidable to his

colleagues and a wayward and independent force in the Cabinet.1

With friends to be fed and a majority to be kept up, the temptations were strong. Ministers faced a barrage of

fawning flattery alternating with outraged denunciation. 'My Lord', wrote a naval Commander-in-Chief to Lord

George Germain, 'the very idea in having thought my conduct worthy of your notice and approbation transports me

almost to a frenzy.'2 The importunities to which Sandwich was exposed are astonishing. His patronage papers are

full of them: of Collier's complaint on being sent to sea just before a parliamentary election; Captain Cornwallis's

untimely remonstrance and hasty apology; Gambier's growing brood of infants and flattery of Sandwich's mistress;

Samuel Graves's innumerable nephews. One is led to ask whether a professional First Lord like Anson would have

tolerated such insolence; and, indeed, whether it was Sandwich's resistance to private importunity rather than his

compliance with it which caused the feeling against him. Royal patronage might have saved him much

unpleasantness, though it would have reduced his influence.

Against the ravening hordes of suitors it was not easy to hold out. Yet on the whole Sandwich withstood the

pressure well. His appointment books reveal how few appointments were available to satisfy the torrent of

applications, and how seldom influence prevailed. Even Middleton's complaints of political appointments in the

dockyards do not stand up to scrutiny. The real source of trouble in the navy did not lie in Sandwich's general

handling of appointments.3

Some of the trouble lay in the characters of naval officers. As the urbane Rodney observed, sea officers were a

censorious lot. Living together in seaport towns, they knew little of the world: hence their violence in party, their

partiality to those who had sailed with them, their gross injustice to others.4 Combined with a spleen strained by

heavy eating and drinking in the confinement of a ship, it was a formidable recipe to nourish faction. These

footballs of fortune5 were ill-equipped to do justice even to the most scrupulous of civil administrators.

1 Christie, 2036; Sutherland, East India Company in Eighteenth-Century Politics, 271, 2779; Wraxall

Memoirs, II, 507; Sandwich, III, 17981.

2 CL, Germain, 13 Sept. 1780, Arbuthnot to Germain.

3 Mr M.J. Williams has analysed the Appointment Books and produced remarkable figures in defence of the

disinterestedness of Sandwich's practice (pp. 233, 2667, 2734). For Middleton, see ibid., 2812.

4 Mundy, Life of Rodney, II, 358.

5 Admiral Lord Shuldham: 'I have been made the football of fortune my whole life' (William Transcripts, 28?

Aug. 1777).

< previous page page_11 next page >