Luscombe D., Riley-Smith J. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 4: c. 1024-c. 1198, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the twelfth century 601

0204060 100 km

020 60 miles

80

40

N

UÍ

THUIRTRE

DÁL

N

ARAIDE

Ulfreksfiord

INIS

EÓGAIN

CIANNACHTA

CENÉL

CONAILL

CENÉL MOEN

MAG

N

ÍTHA

THE NORTH

TÍR EÓGAIN

CENÉL

FERADAIG

FIR

LUIRG

TUATH

RÁTHA

FIR MANACH

MUGDORNA

IND

AIRTHIR

UÍ

BRIUIN

BRÉIFNE

MAG

LUIRG

SÍL

MUIREDAIG

UÍ FIACHRACH

MUAIDE

FIR

UMAILL

LUIGNE

MAG

SEÓLA

IARCHONNACHT

CAIRPRE

DÁL

FIATACH

UÍ ECHACH

COBA

UÍ MÉITH

MACHAIRE

GAILENG

BREGA

FINE

GALL

CAIRPRE

TÍR

AILELLA

LETH

CONNACHT

TETHBA

UÍ MAINE

C

E

N

É

L

BRÉIFNE

CONMAICNE

RÉIN

MEATH

UÍ FAILGE

LÓEGAIRE

UÍ DÚNCHADA

FERNMAG

CUINN

AIRGIALLA

ULSTER

C

E

N

É

L

N

E

Ó

G

A

I

N

UÍ

FIACHRACH

AIDNE

CORCO

BAISCINN

CORCO

MRUAD

DÁL

CAIS

THOMOND

MUNSTER

DESMOND

CORCO

DUIBNE

CORCO

LOÍGDE

CENÉL LÓEGAIRE

EÓGANACHT

LOCHA

LÉIN

EÓGANACHT

GLENDAMNA

UÍ

FIDGENTE

CIARRAIGE

LUACHRA

LETH

ORMOND

DÉISE

MUMAN

UÍ

LIATHÁIN

ÉILE

UÍ

DEGA

LOÍGES

MOGA

LEINSTER

UÍ MUIREDAIG

FIACHACH

UÍ FÁELÁIN

UÍ

BAIRRCHE

OSRAIGE

FOTHAIRT

UÍ

CHENNSELAIG

Coleraine

Maghera

Derry

Aileach

Raphoe

Clogher

Clones

Armagh

Dromore

Downpatrick

Connor

Newry

Louth

Collooney

Drumcliffe

Mayo

Roscommon

Dunmore

Tuam

Ardagh

Clonard

Achonry

Killala

Galway

Tar a

Kells

Slane

Mellifont

Termonfeckin

Dublin

Clane

Naas

Athlone

Durrow

Rahan

Ballinasloe

Clonfert

Wicklow

Arklow

Castledermot

Ferns

Killenny

Leighlin

Baltinglass

Glendalough

Kildare

Monasterevin

Wexford

Waterford

Ter ryglass

Roscrea

Aghaboe

Kilcooley

Kilkenny

Cashel

Holycross

Killaloe

Ardmore

Fermoy

Lismore

Cork

Cloyne

Ross

Limerick

Mungret

Kilfenora

Kilmacduagh

Corcomroe

Ardfert

Emly

Inislounaght

B

a

n

n

o

w

B

a

y

Bangor

Drogheda

Clonmacnoise

Táiltiu

Elphin

Aghadoe

Scattery Is.

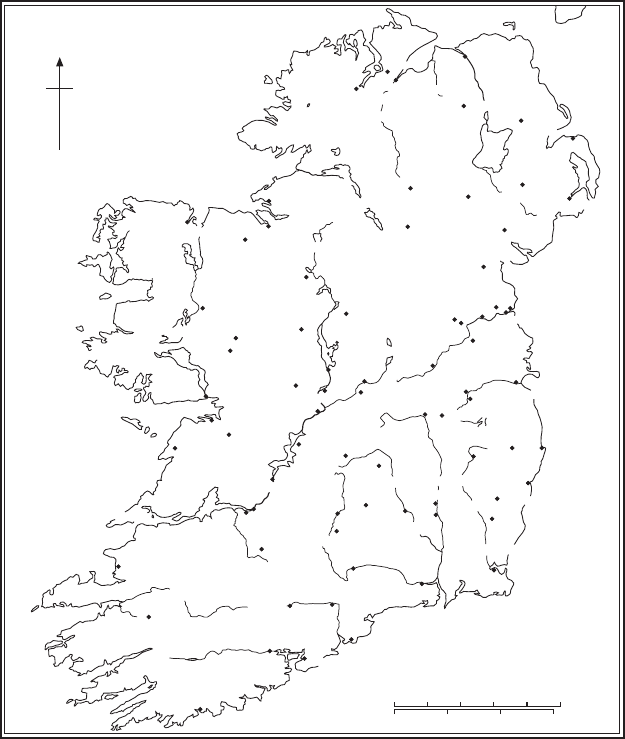

Map 15 Ireland, c. 1160

Ireland. This in turn led to the establishment by 1185 of an Angevin lordship

of Ireland, nominally held by Henry II’s youngest son John, and in principle

embracing the entire island. The Angevin or (as it would better be called)

English conquest of Ireland ought not to obscure the fundamental process of

reorientation which Irish society had begun to experience by the third quarter

of the eleventh century and which continued during the twelfth. The isolation

of Ireland must not be exaggerated. In the Viking era the island had been

plundered again and again by Scandinavian raiding parties. In the course of

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

602 geoffrey barrow

time a few carefully selected coastal sites at the mouths of important rivers –

Dublin, Wexford, Waterford, Cork and Limerick – were permanently settled

by ‘Ostmen’, Danes and Norwegians for the most part, whose careers as part-

time merchants, part-time pirates led them to establish small trading towns of a

type previously unknown in Ireland. The Ostmen communities represented a

significant element of foreign influence and provided an avenue through which

alien ideas, commodities, fashions and individuals could gain a foothold in a

country noted for its social conservatism.

Ireland, lying on the north-western edge of Christian Europe, was in many

respects favoured by nature. Abundance of pasture for cattle and sheep, abun-

dance of peat for fuel, abundance of oak and other woods to provide pannage

for pigs, abundance of game (even though wolves and foxes were not uncom-

mon), abundance of salmon and trout in lochs and rivers, a sufficiency in many

regions of land fit for tillage – all this, with a population scarcely pressing at the

margins of survival, made for an internally self-sufficient, prosperous economy.

Aprevailing mild climate admittedly went hand in hand with a high average

rainfall, and the country was certainly not free from visitations of disease af-

flicting humans and animals alike. But although luxuries such as wine, fine

cloth and precious metals had to be imported, Ireland possessed the resources

necessary to support comfortably, in most years, a simple and healthy way of

life. Human fertility seems to have been at a high level, the universal practice

of polygamy producing an endless supply of male and female offspring. It may,

indeed, be no exaggeration to say that the ruling order in Ireland, a warrior

aristocracy not far removed from the later Iron Age in its culture and outlook,

had too easy a time of it, and were too ready to indulge in inter-tribal warfare

and competition for cattle, slaves, land and prestige.

It was particularly in matters relating to the church and especially to ecclesi-

astical organization that Ireland became receptive to external influences by the

middle of the eleventh century. Irish notables had gone to Rome as pilgrims,

Irish clerics had corresponded with the churches of Canterbury and Worcester.

Significantly, there were links between Canterbury and the episcopal see estab-

lished at Dublin by one of the Ostmen kings who had travelled to Rome as a

pilgrim. A priest named Patrick had been consecrated bishop of Dublin in 1074

by Lanfranc, the archbishop appointed by William the Conqueror. His two

successors had been monks at English Benedictine monasteries, the second of

them consecrated by Archbishop Anselm. It is evident that as far as Britain and

Ireland were concerned the church of Canterbury, secure in its possession of

the primacy of ‘all Britain’, was more consciously and consistently imperialist

than the post-Conquest English monarchy. The church of York, with its claims

to supremacy over the Scottish sees, was hardly less imperialist in its outlook.

The problem for Irish bishops and other clergy who had personal experience

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the twelfth century 603

of the papacy and the church of western Christendom generally, including

England, was that they earnestly wished to carry through a drastic reform and

reorganization of their own church without simultaneously paving the way for

an intrusive domination by English archbishops.

As it was, both Lanfranc and Anselm urged reform upon high kings of

Ireland, respectively Toirdelbach (Turlough) Ua Briain and his son Muircher-

tach, of one of the royal lines of Munster. It was the latter who convened the

first of a series of councils intended to reform the Irish church along Gregorian

lines. It met in 1101 at Cashel, an ancient royal site which was solemnly handed

over to the church by King Muirchertach free of all secular burdens. Maol

´

ısu Ua

hAinmire ‘chief bishop of Munster’ presided over the council explicitly as papal

legate. The business embraced the liberation of the clergy from lay control,

clerical celibacy and privileges, the de-tribalizing of the ancient monasteries

and an attack, which was to prove quite unsuccessful, upon the immemorial

and clearly un-Christian Irish marriage customs, which permitted concubi-

nage, wife-swapping and easy divorce. A dramatic consequence of the council

of Cashel was the decision of Cellach, hereditary coarb (‘heir’ of St Patrick)

of the monastery of Armagh, to become ordained and consecrated as priest

and bishop in 1105–6.Because of its traditional associations with St Patrick,

Armagh had long enjoyed pre-eminence among Irish churches. The conver-

sion of its hereditary leader to the reform programme was thus of the greatest

significance.

Ostmen and purely Irish strains mingled when the Ua Briain dynasty of

Munster made Limerick their chief place about the turn of the century. A see

was established whose first holder, an Irishman named Gilla Espuic (englished

as Gilbert), threw himself vigorously into the cause of reform. He acted as papal

legate for over a quarter of a century and wrote a treatise on ecclesiastical order.

He was a friend of Anselm without allowing his church to become subordinate

to Canterbury. Under his direction the clergy of all Ireland, north and south,

met at Rathbreasail, near Cashel, in 1111, and promulgated legislation which

inaugurated a fundamental restructuring of the Irish church. Traditionally,

Ireland had been divided into two parts, north (‘Conn’s Half’, Leth Cuinn)

and south (‘Mogh’s Half’, Leth Moga), the notional boundary running approx-

imately from Galway Bay across to Dublin. Armagh was indisputably the chief

church of the northern province and Cashel now took the leading place in

the south. To Armagh were assigned twelve bishoprics, in addition to its own,

and to Cashel ten. Because of its close link with Canterbury the status of the

see of Dublin was left in the air. Twenty-five dioceses (soon to be twenty-six

when Clonmacnoise was added) were clearly too many, yet the figure repre-

sented a drastic reduction from the total in earlier times. Archbishop Cellach

of Armagh died in 1129 and was succeeded not by the candidate put forward by

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

604 geoffrey barrow

his own clan, Ui Sinaich, who had monopolized the church since 996, but by

the learned monk and teacher Maol Maodoc Ua Morgair (St Malachy), who

was passionately committed to the cause of reform. For almost twenty years,

till his death in 1148,Malachy steered the Irish church by example and exhor-

tation, introducing at Armagh the use of liturgical music, regular confession,

confirmation and marriage as a religious sacrament. As bishop of Down and

Connor before 1129 Malachy had already reformed the old monastery of Bangor

as an Augustinian house; in 1140 he paid a visit to Rome, travelling by way

of Clairvaux and becoming the firm friend of St Bernard. The introduction

of the Cistercian order into Ireland, of the utmost importance for the suc-

cess of church reform, resulted from this journey. Mellifont, beside Drogheda,

founded in 1142, was the first of a family of no fewer than twenty-one Cistercian

abbeys spread across Ireland mainly in Meath, Leinster and Munster, but also

appearing in Ulster and Connacht, all founded before 1230.Until the thir-

teenth century the order played a notable part in furtherance of ecclesiastical

reform. Mellifont itself, consecrated in 1157, when it was the largest church

so far to be built in Ireland, represented the outward and physical aspect of

reform and innovation. Malachy’s zeal for reform, however, did not confine

itself to Cistercian channels. He grasped the relevance of the Augustinian way

of life for Irish society, and under his auspices old churches were turned over

to communities of Augustinian canons, and new houses were founded, so that

over sixty monasteries of this order had come into existence before the English

invasion. All this reforming activity brought foreign influences into the island,

pointing church and clergy, if hardly yet the laity, in a markedly more Roman

direction. One fascinating example of foreign influence was the decision by

Irish monks in some of the Schottenkl

¨

oster (‘Irish monasteries’) in southern

Germany to come back to their homeland and bring Benedictine monachism

with them. Thus in the 1130s monks from W

¨

urzburg established a house at

Cashel.

The culminating point in the movement of church reform came in 1151–2,

some years after Malachy’s death but very much under his impetus. A papal

legate, Cardinal John Paparo, came to Ireland in response to a request sent

to the papacy by the kings and clergy, and convened a great synod which

held sessions in Meath at Kells and, probably, at Mellifont. A comprehensive

programme of reforming legislation was promulgated, addressed mainly to

the issues of simony, the law of marriage and sexual irregularities and the

payment of tithes, which was an essential precondition for an effective parochial

system. But the synod of Kells is chiefly remembered for establishing the

provincial and diocesan system which prevailed until the sixteenth century

and later. Cardinal Paparo brought no fewer than four pallia (the strips of

cloth symbolizing metropolitan authority). There were to be archbishops at

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the twelfth century 605

Armagh (for Ulster and Meath, but also, as primate, for all Ireland), Cashel

(for Munster), Tuam (for Connacht) and, somewhat controversially in view

of Armagh’s claim, Dublin (for Leinster). Altogether, some thirty-seven sees

were homologated by Kells, and although the next half-century saw a number

of modifications to the pattern, the diocesan structure of the Irish church

remained broadly that which the synod accepted. The addition of Tuam took

account of the power enjoyed by the Ua Conchobair dynasty in Connacht,

while Dublin’s promotion recognized the importance of the Ostman city and

the Leinster kingship, and was made more acceptable to conservative Irish

clergy by the consecration as second archbishop (1162)ofLorcan Ua Tuathail

(St Laurence O Toole) who has been called ‘a prelate in the Malachian mould’,

and who happened to be the king of Leinster’s brother-in-law.

A small number of highly placed clergy were sufficient to steer the Irish

church as a whole in the direction of the Gregorian reforms, in particular the

separation of the clerical from the lay elements in society, the liberation of the

church from secular control and the establishment of an orderly ecclesiastical

hierarchy. No parallel development of any significance took place within the

ruling orders of secular society. In the century following the Norman Conquest

of England the Irish warrior aristocracy remained largely impervious to external

influences. In Ireland (as in Wales) a large class of free or noble lineages, closely

bound by ties of agnatic kinship, competed for land, power and prestige. It has

been estimated that around 170–80 nobles in twelfth-century Ireland could

claim the style of righ, ‘king’. In the case of the vast majority this meant no

more than that individuals so styled were recognized as chiefs of their lineage,

at best exercising some political authority over a small district which might

represent the tuath or ‘tribe’ of more remote periods. Their own lineage did

not necessarily monopolize the territory of such a district, but every king was

expected to defend the interests of his own clan, and if a lineage expanded a

king’s grandsons and great-grandsons might well elbow out any rival freeholders

who did not belong to the clan, even if they were dependants and adherents.

A militarily successful king at the head of a rapidly growing clan might well

seize fresh territory from his neighbours or from further afield; and all the more

powerful kings were expected as a matter of course to undertake great ‘hostings’

or plundering raids, often traversing many miles of country and penetrating

deep into the territory of a rival ruler in search of cattle, pigs and slaves.

The ruling order was supported by an underclass, of indeterminate size,

consisting of peasants actually holding land, serfs living very much at the will

of their lords and outright slaves, often bought from markets such as Bristol.

Just as, in a society so highly compartmentalized as that of Ireland, there were

hereditary castes of kings, clerics, judges, learned poets and historians, so also

there were hereditary castes of bondmen, tied for ever to a monastic church or

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

606 geoffrey barrow

royal house. Some of these biataigh (‘food providers’), as they were known, were

substantial enough to have their own plough teams and to be burdened with

relatively light labour services in addition to the inevitable food renders and

forced hospitality. But the chief occupation of the peasantry must have been

the tending of cattle, pigs and sheep, the staple of Irish food production. The

biataigh survived recognizably until the fourteenth century, but long before that

the English invaders had brought in a peasant class from Wales and England,

whose function was to intensify the arable cultivation of large areas of Meath

and the lowland parts of Leinster and Munster.

At the summit of the shallow broad-based pyramid of kings were some

six or seven rulers whose lineages had acquired dominant positions in the

ancient provincial divisions of Ireland. Since there were traditionally five of

these provinces, Ulster, Connacht, Meath, Leinster and Munster, there should

have been no more than five provincial royal lineages, the ‘five royal bloods

(races)’ as they were known in later times. But splitting and rivalry had led to

two competing families claiming chief place in both Ulster and Munster, while

there were dynasties in kingdoms of somewhat less than provincial standing,

such as Breifne (Leitrim and north-west Cavan), Airgialla (Monaghan and

Armagh), or Tir Conaill (Donegal), which if opportunity offered might make

a bid for higher kingship. The relationship of these royal houses at the top of

Irish society might be said to have been characterized by a stable state of flux.

At the outset of the twelfth century a degree of supremacy throughout Ireland

was enjoyed by the Ui Briain (O Brian) kings of Munster, two of whom,

Toirdelbach (d. 1086) and his son Muirchertach, held the high kingship in

succession. After the latter lost his kingly power in 1116, the chief of the branch

of the Northern Ui Neill (O Neills) ruling over Aileach (north Donegal),

Domnall MacLochlainn, briefly became high king, but by 1122 the king of

Connacht, Toirdelbach Ua Conchobair (O Connor), rose to power after a

period of destructive raids against his neighbours both south and north and,

quite exceptionally, held the high kingship ‘without opposition’ for thirty-four

years. For the next ten years (1156–66) the position reverted to the Ui Lochlainn

of the north, in the person of Muirchertach MacLochlainn. On the eve of the

English invasions Muirchertach was brought low and finally slain as a result

of his own treachery and cruelty, and the chief of the Ui Conchobair, Ruaidri

(Rory), made himself high king, but only ‘with opposition’.

High kingship was essentially a matter of prestige; the position conferred

hardly any concrete powers on its holder, save that deference would be shown,

and if any decisions affecting the whole island were required (including its

defence from external attack) it would be expected that the high king would

take the initiative. Power was acquired by great ‘hostings’; it was maintained by

the immemorial custom of keeping hostages, usually the sons or other kindred

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the twelfth century 607

of potentially hostile kings. Rulers who persisted in being recalcitrant might

be blinded or otherwise mutilated, and the same cruelties were often practised

upon brothers or cousins of a reigning king. Traditionally, it was the high kings

who convened the famous Fair of T

´

ailtiu (Teltown in Meath), a great gathering

of all Ireland where bardic poetry and song mingled with barter and trade and

where important judgements were pronounced and irregular marriages were

entered into.

The elevation of MacLochlainn to the high kingship (consolidated in 1161)

strengthened the position of his ally the king of Leinster, Diarmaid MacMur-

chada (Dermot Macmurrough). Between them they established the saintly

Lorcan Ua Tuathail, Diarmaid’s brother-in-law, in the archdiocese of Dublin.

Dublin, under its own petty ruler, acknowledged Diarmaid as ‘over king’ and

MacLochlainn as even higher. Inspired by tales of ancestral prowess preserved

in the great story-cycles in whose collection Leinster’s learned men were espe-

cially active, Diarmaid sought to exalt the position of his kin and province. He

successfully attacked Ostmen seaports such as Waterford and rival but subor-

dinate kings in north Leinster. Aware that his strongest enemies were the kings

of Connacht and their dependants, the rulers of Breifne, he allied himself to

MacLochlainn: in 1152 the beautiful wife of the king of Breifne, Dervorguilla,

had arranged for Diarmaid to carry her off to Leinster as his mistress, a grave

affront to the dignity of her husband Tighernan Ua Ruairc (O Rourke).

The hatred which Muirchertach MacLochlainn aroused among lesser north-

ern rulers in Ulaidh or Ulidia (north-east Ulster) and Airgialla led to his over-

throw and death in battle in 1166. The Connacht star was now in the ascendant,

and although Dervorguilla had long since returned to Ua Ruairc, Tighernan

seized the opportunity to attack Leinster in force, assisted by Diarmaid Ua

Maelsechlainn (O Melaghlin) king of Meath. Diarmaid MacMurchada’s chief

seat at Ferns was devastated, and Diarmaid himself, despairing of finding any

allies in Ireland, fled to Bristol where he was befriended by the chief burgess

Robert fitz Harding. The king of Leinster sought out Henry II in Gascony,

did homage and requested assistance to recover his inheritance. Henry had

harboured thoughts of Irish conquest since the beginning of his reign when

Pope Adrian IV had authorized an English conquest of Ireland in the famous

bull Laudabiliter, accompanied by a symbolic emerald ring. In 1166,however,

Henry merely issued letters inviting his lieges to come to Diarmaid’s succour.

Ayear after fleeing Ireland Diarmaid returned with a mere handful of Flemish

adventurers from Pembrokeshire. But he had made a fateful bargain with the

earl of Pembroke, Richard fitz Gilbert of Clare, known as ‘Strongbow’, whereby

the earl would bring an army to conquer Leinster, receiving Diarmaid’s daugh-

ter Aoife (Eva) to wife and with her – quite improperly in terms of Irish law –

the succession to the kingdom of Leinster.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

608 geoffrey barrow

Another year passed before Diarmaid’s plans began to mature. In May 1169 a

substantial force of ‘Norman’ feudatories from south Wales, led by Maurice of

Prendergast and Robert fitz Stephen, sailed to Bannow Bay between Waterford

and Wexford, promptly capturing the latter town. They then secured most of

Leinster for Diarmaid but had to confront a great hosting by Ua Conchobair,

who was anxious to assert his overlordship and also to rid Ireland of the dan-

gerous foreigners. The high king made Diarmaid promise to bring over no

additional troops and to repatriate those already in Ireland as soon as Leinster

was fully under Diarmaid’s control. Thus matters rested until the spring of 1170,

when Maurice fitz Gerald (fitz Stephen’s half-brother) and Raymond ‘le Gros’

of Carew came over with reinforcements, as an advance party for Strongbow.

The earl himself, with a much larger force of knights, men-at-arms and archers,

landed near Waterford in August, took the city by storm and soon afterwards

married King Diarmaid’s daughter. The English conquest may be dated from

these events, although it still had a long way to go. Dublin was seen by the

invaders as an essential goal. Not only was it the chief urban settlement of

Ireland, it had acquired some of the characteristics of a capital; and it has been

remarked that no one made himself high king without securing the loyalty

and support of the men of Dublin. Strongbow and Diarmaid (aspiring to the

high kingship) accordingly laid siege to Dublin, evading the sprawling, undis-

ciplined army brought to its rescue by Ruaidri Ua Conchobair. The city fell to

a surprise attack (21 September 1170) and in the following summer the tables

were turned as an immense host, drawn by the king of Connacht from almost

every part of the island, encamped to the west of Dublin, awaiting a sea-borne

attack upon the English garrison by Scandinavians from the isles rallying to the

cause of their Ostmen kindred. Against all the odds Strongbow’s knights and

archers put the Irish host to flight with great slaughter and also destroyed the

much better-disciplined and better-equipped Norse army. With these victories

the earl of Pembroke and his followers had effectively conquered Ireland, not

for Diarmaid, who died in May 1171, and not even for themselves, but for their

lord, Henry II.

The king crossed to Waterford on 17 October 1171 with some 4,000 troops,

including 500 cavalry. No native Irish host could have withstood such a

force, but Henry’s purpose seems rather to have been a public assertion of

sovereignty. Many kings and lesser chiefs submitted, following the lead given

by the two kings of Munster, MacCarthy of Desmond and Ua Briain (O Brien)

of Thomond. Strongbow had prudently surrendered all his conquests. He re-

ceived Leinster back as a fief, not a kingdom, to be held for 100 knights’

service, and without the Ostmen cities of Dublin, Wexford and Waterford

which with their hinterlands were kept as crown demesne. Meath was given to

Hugh of Lacy for fifty knights, along with the office of justiciar. No attempt

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the twelfth century 609

was made to enforce the submission of Ua Conchobair the high king, or of

the north-western potentates Ua Neill of Aileach, and Ua Domhnaill of Tir

Conaill (Donegal). In 1175 Ua Conchobair agreed to the treaty of Windsor,

which placed him in a clearly subordinate position, holding Connacht for an-

nual tribute. He was allowed an ill-defined lordship over such Irish kings as

were not already subject to English rule, making himself responsible for the

regular payment of their tribute.

Henry II spent the winter of 1171–2 in Ireland, entering Dublin at Martinmas

(11 November) and lodging in a ‘palace’ built of wattle and thatch in the

Irish style. He was open-handed towards the Irish kings and suspicious of the

free-lance adventurers who had preceded him. Delayed by stormy weather, he

eventually returned to Britain on 17 April 1172.His most enduring achievement

had been to give a decisive change of direction to the reform movement in

the church. A synod assembled at Cashel while Henry was still in Ireland.

It reiterated and confirmed reform measures agreed by earlier councils, but

significantly concluded with an undertaking to adopt the church in England

as the model for Irish religious life. From 1181 the archbishops of Dublin were

invariably English and the see itself, though unable to oust Armagh from its

primacy, came increasingly to assume an ecclesiastical status parallel to the

secular role of Dublin as the seat of Angevin royal government. A series of

powerfully worded letters from Pope Alexander III reinforced Laudabiliter and

set the church’s seal of approval on the Henrician conquest.

Three themes predominated in Irish history from the Conquest till the end

of the twelfth century and, indeed, till the end of King John’s reign (1216). First,

the Angevin monarchy sought to establish an administration for Ireland, based

on Dublin and modelled on English (rather than continental) lines. In 1177

Henry II’s youngest son John was made ‘lord of Ireland’. Hugh of Lacy would

govern in his name, as justiciar, supported by Meath which he was now to hold

feudally for 100 knights’ service. John visited his lordship in person in 1185,

replacing Hugh of Lacy by John of Courcy and making many land grants to his

followers. After John succeeded Richard I on the throne Ireland was assimilated

more decisively to the English model. Dublin Castle was built as government’s

headquarters, royal courts and a fiscal and financial system were established,

while a reproduction of English law came into force, soon to be known as the

‘Customs of Ireland’. A second theme, closely connected with the first, was

provided by the crown’s suspicion and jealousy of the nobler English settlers,

towards whom it pursued an ambivalent policy of encouragement by land

grants and discouragement through confiscation or overt support for native

Irish rulers against their would-be supplanters. Certainly the English conquest

proceeded inexorably despite the treaty of Windsor. In Munster MacCarthy

of Desmond and Ua Briain of Thomond were displaced with the English

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

610 geoffrey barrow

crown’s connivance. In eastern Ulster the whole structure of native kingship

was toppled by the startlingly rapid free-lance conquest carried out in 1177 by

John of Courcy, who held on to his huge gains till 1205 and showed some signs

of turning himself into a potentate of thoroughly indigenous type. To offset

these private conquests (of which John of Courcy’s was merely the largest and

most dramatic), the crown appointed a series of non-settler officials, justiciars,

sheriffs and the rest, who were intended to counterbalance the power of settled

feudatories. The flaw in this policy lay in the fact that officials who spent

more than a brief period in Ireland became effectively settlers themselves and

quickly developed settler interests. The final and, as it proved, perpetual theme

to dominate the history of Ireland in this period was provided by the Irish, and

especially by the survivors of the ruling lineages. In the earlier 1170s the tribal

kings failed to grasp the implications of Angevin overlordship. Foreigners in

mail hauberks could be absorbed and assimilated, and the English crown would

defend the Irish kings against further encroachment. After Strongbow’s death

in 1176 came severe disillusionment, as Ulster was overrun and the newcomers

took over large areas of Munster, while the lower-lying and more fertile parts

of Leinster and Meath become intensively feudalized. Even Connacht was

attacked, though here – for almost the first time – the English were defeated

and driven back. Ruaidri Ua Conchobair lived until 1199 and was buried at the

monastery of Cong, near Tuam, for which the great craftsman Maelisa son of

Bratan had fashioned the beautiful cross of Cong on the orders of his father

Toirdelbach Ua Conchobair. At the time of Ruaidri’s death, the old highly

privileged, easy-living, warrior aristocracy of Ireland survived intact only in

Connacht, Tir Conaill and parts of Tyrone (Cen

´

el Eoghan). Elsewhere, power

at the top had passed to foreigners, who imported their own freeholders from

England and Wales, and even, in Leinster and Meath, their own peasantry.

The kin-based Irish tribal groupings lived on in Leinster, Munster and eastern

Ulster, but in a depressed condition and confined largely to the hillier or

less fertile districts. As in Wales, so now in Ireland, Plantagenet England had

succeeded only in bringing into existence two societies and cultures in the same

country.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008