Luscombe D., Riley-Smith J. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 4: c. 1024-c. 1198, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

chapter 19

SCOTLAND, WALES AND IRELAND

IN THE TWELFTH CENTURY

Geoffrey Barrow

for all three of the countries whose development is reviewed in this chapter,

a leading theme was provided by the continuing after-effects of the Norman

Conquest of England, which made themselves felt far into the twelfth century

and beyond. The Norman conquerors and colonizers who flocked to England

in the forty years separating the battles of Hastings and Tinchebray hardly

raised their sights sufficiently to take in southern Scotland and showed almost

no interest in Ireland. There was already in 1066 a lengthy history of close

relations, friendly and unfriendly, between Wessex and Mercia on the one hand

and the Welsh kingdoms or principalities on the other. Even if the Norman

kings had been willing to stand aloof from the situation in Wales the aggressive

and acquisitive conduct of some of their closest followers would have compelled

them to intervene if only to prevent the creation of dangerously independent

lordships on their western frontier. The expansion policy pursued successfully

before 1100 in the north and mid-Wales, and only to a slightly lesser extent in the

south, meant that not only the incoming conquerors but also the Welsh princes

were brought ineluctably within the political segment of north-west Europe

which it is convenient to think of as Anglo-Norman. Moreover, by seizing

the English kingship Duke William automatically became heir to a tradition,

reaching back at least to the tenth century, of English claims to exercise some

kind of lordship over the kings of Scots. Ireland was a different matter, yet

although the Conqueror in 1081 stopped short at St David’s and demanded

no tribute from Irish kings or trading towns the fact that both Lanfranc and

Anselm, as archbishops of Canterbury, laid claim to an ecclesiastical hegemony

over the Irish bishops, together with the occasional freelance venture into Irish

affairs by Norman settlers in Wales such as Arnulf of Montgomery, lord of

Pembroke, kept Ireland in focus as it were, to remain until the 1170s the

greatest single imponderable in English royal policy.

The gradation of dependency in political and military matters set up by the

Norman Conquest, with Wales being brought most closely into the English

581

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

582 geoffrey barrow

ambit, Scotland somewhat less so and Ireland scarcely at all, was not reflected

in the social organization, languages and customs, or religious life of the

three countries under review. Despite the lightning military successes of the

first Normans to penetrate Wales, and the inextricable links forged between

Wales and England by Anglo-Norman settlement, the whole process of castle-

building and colonization suffered major setbacks of long duration, especially

in the reign of Stephen. There is little if any sign that the Welsh language, Welsh

law and custom, or the basic ways in which Welsh society was organized, were

seriously affected, still less threatened, by Anglo-Norman pressure and incur-

sion. Only in the structure, personnel and external relations of the church can

we see specifically English and continental influences being gradually brought

to bear. In Scotland, by contrast, a much more complex situation prevailed.

Wales, politically fragmented to an extraordinary degree, was culturally and

socially remarkably homogeneous. Scotland, politically speaking, formed a

recognizably single entity, a kingdom with a history of some three to four cen-

turies. This kingdom, which had not yet taken the geographical shape familiar

since 1266 (save for the important addition of the Northern Isles two centuries

later), was composed of elements diverse in language, law and social organiza-

tion, although not differing significantly in general culture. The south-east part

of Scotland, especially Lothian, Tweeddale and Teviotdale, together with cer-

tain districts of the middle south, notably Clydesdale, Annandale and Eskdale,

shared many features of social organization, as of basic pastoral economy, with

what are now the northernmost regions of England, especially Cumberland,

Westmorland, Northumberland and County Durham. As these northern ar-

eas were brought more firmly under the control of the English crown, feudal

nobility and church hierarchy, the common features which they shared with

southern Scotland to some extent diminished in importance. But at the same

time (essentially in the twelfth century) many of the innovative features of post-

Conquest English government and social order, especially military feudalism,

were deliberately introduced into Scotland by a line of strong kings. Conse-

quently we have the seeming paradox that c. 1200 Scotland was in important

respects less different from England than Wales was, despite the closer depen-

dence of the Welsh princes upon the English crown. Ireland, in comparison

with both Scotland and Wales, seems to pass from one extreme to the other.

Until 1171 the Irish kings and the trading communities founded by the ‘Ostmen’

or Norse-speaking Scandinavians enjoyed somewhat restricted relations with

the new political forces east of the Irish Sea but were in no way subordinate to

them. After the Henrician conquest a large part of Ireland suddenly became an

Angevin province, more tightly controlled in the name of the English crown

than almost any part of Wales. Nevertheless, save in the towns such as Dublin,

Waterford and Limerick which had never known a predominantly Irish form

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the twelfth century 583

of society, the island as a whole had, like Wales, a remarkably homogeneous

social system. Despite an influx of Anglo-Norman – by 1171 it would be more

accurate to call them ‘English’ – settlers, barons, knights, esquires, freeholding

yet dependent tenants, as well as of vitally important merchants, craftsmen and

clergy, the vast majority of the population continued to owe their first loyalty

to kings of various grades whose power and prestige cemented the immemorial

kin-based character of Irish society. The strength of traditional custom and

the autonomous nature of Irish law, administered almost independently of

the kings by a hereditary caste of breamhan (judges), made Irish society even

more impervious to external influences than was Welsh society, although it

may readily be recognized that the systems of both countries had much in

common.

It has long been usual for historians to sum up and explain the common

features observable in Welsh, Irish and at least northern Scottish society by

classifying them as ‘Celtic’. This practice rests on a fundamental truth, namely

that the peoples who used one or other of the Celtic languages – Irish and

its Scottish derivative, in the twelfth century only just becoming distinctively

‘Scottish Gaelic’, the closely related Manx form of Gaelic, Cumbric (so far as

it still survived after c. 1100) and Welsh – did also hold fast to social customs

and modes of organization, and to legal concepts and practices, for which

there was almost a common Celtic vocabulary. Nevertheless, the blanket word

Celtic ought to be used with caution and discrimination. In the first place, the

use of a particular language or family of languages does not necessarily imply

adherence to any particular pattern of social customs. Secondly, there is the

implied assumption that the patterns of marriage, inheritance and landholding

familiar in Celtic kin-based society had been frozen at some remote period and

remained almost immutable throughout the middle ages. Finally, to explain

the persistent features of Welsh, Irish and Scottish society solely in terms of a

Celtic kin-based system is to underestimate the extent to which several of these

features – the importance of agnatic relationships, for example, or the concept

of the honour price and man-price (wergild ), or fosterage – were common to

many of the barbarian peoples of northern Europe. To adapt a phrase made

famous by F. W. Maitland, ‘We must be careful how we use our Celt.’ The

one certainty which may be affirmed is that, by comparison with Norman-

conquered England, Ireland, Wales and Scotland – especially the first two –

displayed a remarkable degree of social and legal conservatism.

scotland

Only five kings reigned over Scotland in the twelfth century, and the last three

of these ruled from 1124 to 1214.AsinEngland, long reigns made for political

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

584 geoffrey barrow

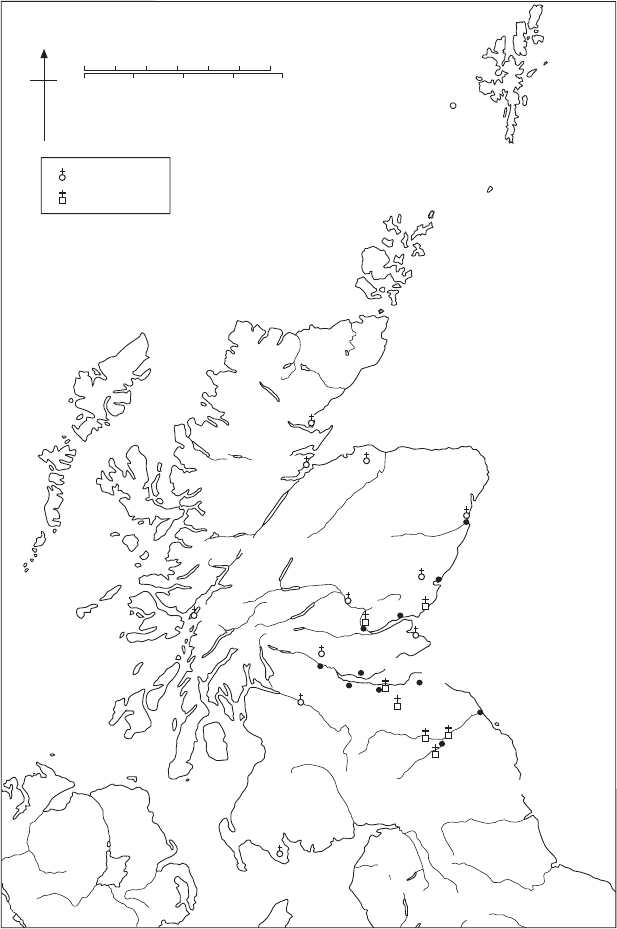

N

0255075 150 km

025 100 miles

100 125

50 75

Aberdeen

Montrose

Dundee

Perth

Stirling

Glasgow

Edinburgh

Dunfermline

Linlithgow

Berwick

Kelso

Jedburgh

Haddington

Melrose

C

l

y

d

e

T

w

e

e

d

T

e

v

i

o

t

S

T

R

A

T

H

C

L

Y

D

E

GALLOWAY

AY

R

S

H

I

R

E

ARGYLL

H

E

B

R

I

D

E

S

ORKNEY

SHETLAND

St Andrews

M

o

r

a

y

F

i

rt

h

S

o

l

w

a

y

F

i

r

t

h

ISLE

OF MAN

NORTHUMBERLAND

DURHAM

WEST-

MORLAND

YORKSHIRE

C

U

M

B

R

I

A

SCOTLAND

(ALBA)

Holyrood

A

N

N

A

N

D

AL

E

E

S

K

D

A

L

E

LO

Newbattle

Roxburgh

Bishoprics

Monasteries

Dunkeld

Scone

Elgin

(Moray)

Fortrose

(Ross)

Dornoch

(Caithness)

KINTYRE

Brechin

Dunblane

Whithorn

Arbroath

Lismore

(Argyll)

Map 13 Scotland

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the twelfth century 585

stability, strengthened by the fact that the five rulers represented only two differ-

ent generations. Three brothers, Edgar (1097–1107), Alexander I (1107–24) and

David I (1124–53), were followed by David’s two older grandsons, Malcolm IV

(1153–65) and William I ‘the Lion’ (1165–1214). The dynasty to which they

belonged was held to be in direct succession to the Cen

´

el nGabr

´

ain which

had held the kingship of Scottish Dalriada until the eighth century. Their un-

doubted ancestor was Kenneth Mac Alpin (d. 858). Rightly or wrongly he was

believed to have inherited the royal authority not only of Dalriada but also of

the old Pictish kingdom of Alba (Scotland north of the Forth–Clyde isthmus

and east of Argyll). Consequently, the twelfth-century kings enjoyed a native

and traditional prestige and respect which did not depend on the military

power at their disposal.

It was the royal house which imposed and encouraged such unity as ex-

isted in the Scottish realm. Alba, together with mainland Argyll, was relatively

homogeneous: Gaelic in speech and, largely, in culture, composed of ancient

territorial divisions ruled by mormaers (essentially provincial governors, yet

having some kingly quality attaching to them), served by a church which, in

spite of continental and English influences operating from the eighth to the

eleventh century, still possessed many features characteristic of the Irish church,

strongly kin-based in its social organization which (as in Ireland) penetrated

the clergy as well as the laity. Only in two important respects may any sign

of a fundamental break with tradition be seen before 1100 – both attributable

to continental and English influence. The older practice of royal succession

whereby an adult collateral – brother or cousin – was preferred to a son was

defied when a rebellion in favour of Donald B

´

an, Malcolm III’s brother, was

finally defeated in 1097 and the throne was taken by Edgar, Malcolm’s fourth

son. Native sensitivities may have been allayed by the succession in turn of

Edgar’s two younger brothers, but in 1153 the profoundly important switch

to linear parent-to-child succession was highlighted by the acceptance (with

seemingly only minor resistance) of David I’s eldest grandson, Malcolm IV.

HisGaelic name (the last ever borne by a king of Scots), and the fact that he

was followed by his brother, may again have appeased the conservative nobility,

who gave only half-hearted support to collateral rival claimants for the king-

ship under William the Lion; but some faint hankerings after the old custom

can still be seen even in the thirteenth century.

The second significant change discernible before 1100 was the advent of

military feudalism, that is to say the granting of land (in the first instance by

the crown) on privileged terms, usually with jurisdiction and the right to build

castles, in return for the performance of military service with horses trained

for warfare and with expensive armour and weaponry. Under Malcolm III

and Edgar the impact of feudal lordships held for knight-service was slight

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

586 geoffrey barrow

and chiefly confined to Lothian. But the process had come to stay and, quick-

ening appreciably under Alexander I, became the predominant fashion of land-

holding across much of southern Scotland in the reign of David I. Large estates

were created in this way in the period c. 1120– c. 1170, and although the impetus

behind feudalization hardly slackened before Alexander II’s reign the emphasis

shifted to smaller fiefs (parish or village sized) and towards the country north

of the Forth, at least as far as the Moray Firth.

The patchy advance of military feudalism underlines the geographical di-

visions which retained both social and political importance at least until the

thirteenth century. South-eastern Scotland still bore many traces of its earlier

history as part of Bernicia or northern Northumbria. The northernmost ver-

sion of English speech was standard from Annandale eastward to Berwickshire,

and had long since obtained a firm hold upon Mid and East Lothian, where it

had been marginally challenged by Gaelic since the mid-tenth century. Below

the crown, whose demesne lands were very extensive, a native aristocracy of

service and status (‘thegns’ or ‘thanes’) held sway over a semi-free or even free

peasantry whose obligations to their lords took the not notably onerous form

of occasional labour service, especially at harvest time, seasonal renders of food

and hospitality and here and there money rents. Below this class of substantial

‘husbandmen’ there were poorer but not invariably less free ‘cottars’ and graz-

ing tenants (‘gresmen’) whose name reminds us of the strongly pastoral nature

of even south-eastern Scotland.

West of Lothian and the border river systems, the twelfth-century Scottish

kingdom embraced the Clyde valley – politically an important remnant of the

old Cumbric kingdom of Strathclyde, and thoroughly feudalized by the crown

in the period 1150–70 – the Ayrshire littoral, of which the two northern districts

(Cunningham and Kyle) were either royal demesnes or feudal tenancies by 1165,

and the highly distinctive region of Galloway, consisting of the southernmost

district of Ayrshire (Carrick) and the valleys flowing into the Solway Firth,

especially those of Bladnoch, Cree, Dee and Nith. Before 1162 Galloway was

recognized, at least by its own ruling dynasty, as a kingdom, owing only the

most tenuous obedience to the king of Scots. The prevailing Gaelic language

and culture of twelfth-century Galloway was in no sense a contradiction of this

fact, for multiplicity of kingship was the norm throughout Ireland and at least

the western seaboard of Scotland. The reduction of Galloway to the status of

political, though never feudal, subordination was to take the Scottish crown

many years and cost it much in terms of military expeditions, abortive experi-

ments in feudalization and recognition of Gallovidian separateness. The whole

process began in earnest under Malcolm IV and was not completed till 1235.

Of the remaining regions making up modern Scotland the northern isles of

Orkney and Shetland, subject to dense Norwegian settlement since the early

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the twelfth century 587

ninth century, did not become part of the Scottish realm until 1468–9. The

western isles and the westernmost districts of the mainland (including what

medieval people called the ‘Isle of Kintyre’) formed a complex area in which

cultures clashed and intermingled and political claims were a bone of con-

tention between Scottish and Norwegian rulers. An agreement between Edgar

and Magnus ‘Barelegs’ stipulated that the western isles (including Man but per-

haps excluding the islands in the Firth of Clyde) should be subject to Norwegian

rule while the mainland seaboard acknowledged Scottish sovereignty. Although

not unworkable (the agreement was only cancelled by the treaty of Perth in

1266), it was unsatisfactory because actual lordship – often seen as ‘kingship’

in the Irish sense – in the west crossed interregnal boundaries and embraced

both mainland and insular territories. Thus many local lords, and particularly

the powerful family of Somerled ‘king’ of Argyll, held sway, with the help of

fast galleys, over groups of islands where they were nominally lieges of a remote

Norwegian king and districts such as Lorn and Cowal where, again somewhat

nominally, they were subjects of the king of Scots. David I exercised some

measure of royal authority in the west and could even call out troops from this

region in time of emergency. Malcolm IV’s forces repulsed an invasion by west

highlanders and islesmen in 1164 in which Somerled was slain. During the long

reign of William the Lion the west remained comparatively peaceful, yet there

is little doubt that dynastic rebellions against William’s rule, notably in 1187

and 1212,drew their military support from the isles and the western seaboard.

Neither geographical and cultural diversity nor lingering provincial sep-

aratism should obscure the strong currents flowing throughout the twelfth

century in the direction of political and national unity. The introduction of

feudalism at the crown’s behest proceeded apace from c. 1120 to c. 1220, and

with remarkably little friction. In origin partly functional and partly social,

the Scottish brand of feudalism promoted by David I and his grandsons laid

the foundations not only of the dominant class of ‘lairds’ (tenants-in-chief

of the crown or substantial tenants of the greatest feudatories), who were to

wield decisive power in Scotland until the eighteenth century, but also of

Scottish land law, which remains markedly ‘feudal’ to the present day. The

crown also encouraged the concept of the regnum Scotorum,akingdom of the

Scots which embraced an extent of territory much wider than Alba or Scotia,

taking in Lothian, Strathclyde and Galloway and until 1157 including the coun-

try stretching south from the Solway Firth as far as Stainmore on the northern

edge of Yorkshire. On occasion (e.g. in the later 1130s, in 1163, between 1174

and 1189, and again in 1209 and 1212) the relationship between the Scots and

the English crowns was challenged by English rulers who sought to reestablish

the hegemony which William the Conqueror and his sons had appeared to

enjoy in respect of the Scottish monarchy. David I refrained during Henry I’s

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

588 geoffrey barrow

lifetime from striking an independent pose save in the matter of ecclesiastical

autonomy – he would not allow his bishops to acknowledge the supremacy

of either York or Canterbury. On the accession of Stephen David refused

any kind of homage involving his kingdom, while allowing his son Henry to

swear fealty for the earldom of Northumberland and honour of Huntingdon.

Henry II may have attempted in 1163 to impose some degree of lordship over

Malcolm IV, but it was not until William the Lion was captured by the English

eleven years later, having ill-advisedly supported the Young King’s unsuccessful

revolt, that the king of Scotland, by the treaty of Falaise, was forced to become

the liege man of the English crown ‘for Scotland and his other lands’. This

explicit feudal subjection lasted till 1189, when on Henry II’s death William

bought his release, and restoration of the king of Scots’ position to what it

had been under Malcolm IV, from Richard I. Friendly relations prevailed until

John succeeded his brother in 1199; for the remaining fifteen years of William’s

reign there was mutual suspicion and mistrust between the realms, accompa-

nied by two attempts by John (1209 and 1212)torevert to something like the

Henrician overlordship. Paradoxical as it may seem, the lengthy period dur-

ing which William the Lion was either formally subject to the English crown

or at least under threat from aggressive English royal policy saw the Scottish

king strengthen his political grip upon the more outlying regions, especially

in the highlands and Galloway. The high-handed manner in which Henry II

and John treated William may actually have excited some sympathy among

his own lieges, and there is no doubt that the concept of a Scottish kingdom

whose people owed a special, overriding loyalty to the crown had grown into

areality by the end of the twelfth century.

The population of Scotland, perhaps approaching 350,000 by the end of

the twelfth century, earned its living chiefly by pastoralism and fishing. Cattle

and pigs were owned by all but the poorest families, and the herds kept by the

greatest magnates, for example the lord of Galloway, the earls north of the Forth

or the bishops of St Andrews and Glasgow, would be counted in many hun-

dreds. Sheep too were reared, and their numbers must have increased steadily

through the century as newly founded religious houses began to specialize in

meeting the needs of the Flemish wool markets and the fleece became more

valuable than the flesh. Both cows and ewes were of course bred for their milk

and the butter and cheese to be made from it. Goats were common, valued

for their milk and their skins. Horses – to judge from Pictish sculpture – must

have been familiar long before the Norman adventurers rode into Scotland on

their war-trained destriers, but as with sheep, equine numbers would surely

have risen markedly between 1100 and 1200, and Clydesdale’s reputation for

breeding versatile horses may well date from this period. As for fishing, the

species most frequently appearing in contemporary record are salmon, herring

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the twelfth century 589

and eels. Herring in particular was an estuarine fish in this period (and for

many centuries longer), and fishermen from as far afield as the Low Countries

were visiting the Firth of Forth by the 1150s. A pastoral way of life, with fish-

eries forming a significant supplement to food supplies along the sea shore, as

well as by the numerous rivers and lochs, seems to go naturally hand in hand

with hunting. Much of the land above 400–500m was either too rugged or

too remote for the summer pasturing in ‘shielings’ (transhumance) which was

standard practice throughout Scotland. Nevertheless, such areas carried in the

summer months a sizeable population of red deer, which could normally find

adequate winter shelter in lower-lying woodland, considerably more extensive

than in later centuries. Although in later Scots law, following Justinian, wild

animals were regarded as res nullius, fair game for all, in medieval practice the

pursuit of red deer was a jealously guarded royal right which was extended,

not over-generously, to the higher nobility. Earls and certain of the bishops

enjoyed hunting preserves, as did such notable magnates as the hereditary

steward (Stewart) and constable or the lord of Annandale (head of the Scottish

branch of the Bruce family). Many tracts of upland and well-wooded ground

in the south and middle parts of Scotland, especially along the ‘highland line’,

were designated forest, in which hunting was controlled and through which

passage was restricted to permitted routes, probably sign-posted. A corollary

of the protection of wild game was the prohibition of tree-cutting and de-

struction of undergrowth and of the eyries of falcons and other birds of prey.

For kings and nobles hunting was undoubtedly a sport, but venison probably

made a significant contribution to the general diet, and it would be naive to

suppose that unprivileged folk, especially in the remoter hill country, did not

poach the occasional salmon or deer. Foxes, wild cat, wild boar and wolves were

also hunted, the last two species to the point of extinction in the sixteenth or

seventeenth centuries.

The predominance of pastoralism in highlands and lowlands alike did not

mean that cereal growing was unimportant. Across much of the flatter or

lower-lying territory of south-eastern Scotland, and along the eastern littoral

as far north as Stonehaven, agriculture in the strict sense had been practised

immemorially. In the course of the twelfth century the area of land brought

into cultivation by ox-drawn ploughs and harrows increased very substantially.

In this period the valley of the Clyde, the Ayrshire coastal strip and sizeable

pockets of favourable terrain along the shores of the Moray Firth witnessed

an extension of arable or its introduction for the first time. The customary

manner of quantifying land in Lothian and Tweeddale was by the ploughgate

(carucata)of104 acres, made up of eight 13-acre oxgangs (bovatae). This usage

was shared with the northernmost part of England, indicating perhaps an

Anglian origin. Whatever its roots, the system emphasized the vital role of the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

590 geoffrey barrow

plough and plough-team of eight oxen in the rural economy. North of Forth

and Clyde, and in earlier periods in the far south-west also, habitable land

was generally divided into davochs (Gaelic dabhach,‘vat’,‘tub’), terminology

which may suggest delving with a spade rather than ploughing, or which might

possibly point to a levy of corn for purposes of rent or tax. Again, the cereal

element is important, yet the emphasis is not on the plough. Crops were

cultivated whenever soil and climate allowed, but the share of rural income

derived from corn was obviously larger in the more favoured lands of southern

and eastern Scotland, smaller in the north and west. Some wheat was grown,

for example in East Lothian and the Carse of Gowrie, but the standard cereals

were rye (perhaps winter sown) and the spring-sown oats and bere, the six-

rowed northern barley preferred until modern times. There is no record of peas

or beans before the thirteenth century, but here and there some flax may have

been cultivated. The typical peasant farmer of the south, the husbandman or

bonder, held a ‘husbandland’ consisting of 26 acres of arable (two oxgangs),

together with a proportional share of hay meadow and pasture in the common

grazing possessed by every permanent settlement. In good years such a holding

might provide a reasonable livelihood for a peasant upper class, but below the

husbandmen were numerous cottars and landless families from whom either

permanent or seasonal labour could be recruited. It is harder to discern a typical

peasant in northern Scotland, yet safe to assume that he kept cattle or pigs and

held only a modicum of arable. Although servitude of a fairly thoroughgoing

nature was by no means unknown in southern Scotland, it seems clear that the

peasantry of Alba were subject to even more oppressive restrictions upon their

freedom than their southern counterparts.

Self-sufficient as the rural communities of twelfth-century Scotland were in

many respects, they needed to sell some of their surplus production and import

goods made in other parts of Scotland or imported from England, Ireland and

the continent of Europe. The aristocracy required fine cloth, jewels, weaponry

and wine, none of which could be produced at home. In times of dearth the

common people might need corn. Trade must have been immemorial, yet the

twelfth century saw two innovations which gave a revolutionary boost to mer-

cantile activity and to general prosperity. The twelfth-century kings – perhaps

beginning with Edgar and Alexander I, certainly maturing with David I –

instituted the earliest explicitly privileged trading communities or ‘burghs’ in

Scotland. Most of the early burghs were on or close to the east coast – Berwick,

Roxburgh, Haddington, Edinburgh, Linlithgow, Stirling, Dunfermline, Perth,

Dundee, Montrose and Aberdeen. Secondly, David I, around 1136,authorized

the first issue of Scottish silver coins, pennies modelled precisely on the sterlings

of English kings but bearing the name and image of the king of Scots. Even

though these new coins were insufficient for Scottish needs their issue ushered

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008