Luscombe D., Riley-Smith J. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 4: c. 1024-c. 1198, Part 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the twelfth century 591

in a new era in which the Scottish economy, backward as it might seem from a

continental European viewpoint, was ultimately money-based. The combina-

tion of small trading centres, whose inhabitants enjoyed ‘first-come first-served’

privileges of trading within carefully demarcated zones, with the regular issue

of silver pennies exchanging at par with English-minted sterlings, gave a boost

to Scottish economic activity which can scarcely be exaggerated. Wool clipped

from increased lowland flocks was sold to Flanders, cow-hides and deerskins

from the highlands went to Germany and France, pearls from Tay and Dee

were sought after by continental jewellers. The trading towns (‘burghs’ is the

Scottish version of English ‘boroughs’) attracted immigration from England,

the Low Countries and Germany as well as from the Scottish hinterland. Even

the highlands were involved in urban development, for although none of the

new burghs was strictly within the highland line, settlements such as Inverness,

Forres, Elgin, Perth, Stirling and Dumbarton lay along that invisible boundary

and served as centres for the exchange of highland produce for foreign man-

ufactures. By 1200, when upwards of thirty burghs had been created, mostly

by the crown, the urban trading centre, with its weekly market and quarterly

or half-yearly fair, had become an integral feature of the country’s social and

economic fabric.

Burghs played a political and administrative as well as an economic role.

It was normal for a royal castle to be sited beside a burgh, and for this castle

to serve as headquarters for a sheriff who acted as the chief agent of royal

government in the district associated with burgh and castle – the sheriffdom

or shire. Smaller and much more ancient districts known as shires, administered

by thanes or sheriffs, still persisted in many parts of twelfth-century Scotland,

but the grander and more powerful sheriffs established by David I were a

conscious imitation of the practice of Norman England. By 1200 the geography

of royal government bore a strong though perhaps superficial resemblance to

the English pattern, with sheriffdoms or ‘counties’ filling almost the whole

of southern and eastern Scotland as far north as Inverness. As yet Galloway

and the highlands were not ‘shired’, but royal authority and the crown’s role

in administering justice did not depend exclusively on the sheriff. David I’s

sheriffs and their successors were drawn mainly from the baronial class, the new

feudal nobility. It was from their ranks, but also from among the older territorial

aristocracy – earls and provincial lords – that the kings appointed their highest

administrative officers, the justiciars. Normally there was one justiciar for the

country north of Forth (Scotia) and one for the south (Lothian), but the

later practice of having a third justiciar for Galloway may have been briefly

anticipated in the 1190s.

In Scotland – contrasting markedly in this respect with twelfth-century

England – the king’s hand did not lie heavy on his lieges year after year in

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

592 geoffrey barrow

terms of taxation or military service or hunting reserves or judicial decrees.

Scottish royal government was no less real for being much less centralized,

much less bureaucratic, than English. It may be no coincidence that the major

officers of the royal household, derived from Anglo-Norman and Capetian

models, especially the steward, constable and marischal, quickly came to fill

a public position within the community of the realm as a whole, taking their

style (though not before the thirteenth century) from the country rather than

merely from the king.

The profound transformation undergone by government and society in

twelfth-century Scotland was matched by a far-reaching reform of the church.

In 1100 a tiny handful of Scottish clergy had attained to the grade of bishop and

there was no territorial diocesan system. There were monasteries north of the

Forthofadecidedly Irish type, in particular communities of c

´

elid

´

e (culdees),

‘clients of God’, who practised an asceticism derived from an eighth- and ninth-

century reformation of Irish monasticism. Ill-defined clerici, some probably in

priests’ orders, were attached to churches and chapels which served the spiri-

tual needs of widely scattered rural communities but were not parochial as that

word was understood in most of western Christendom. South of the Forth a

markedly Northumbrian situation prevailed, with quasi-parochial churches –

some of them classifiable in Anglo-Saxon terms as old minsters – served by

priests who were virtually hereditary proprietors; having succeeded their fa-

thers in the benefice they would in turn expect to pass it on to a chosen son

or grandson. In the view of this somewhat inward-looking and tenuously or-

ganized church the pope was little more than an object of vague and remote

veneration. By 1200 the self-consciously styled ecclesia Scoticana consisted of

eleven territorial dioceses each ruled by a bishop who since 1192 had had to

visit the papal curia to be confirmed in his office. The faithful were allocated

to parishes with fixed boundaries. Groups of parishes formed ‘deaneries of

Christianity’, and in each of the two largest bishoprics of St Andrews and

Glasgow groups of deaneries constituted two archdeaconries. Marriage among

the lesser clergy, and heritable livings, had not yet been eliminated, but the

end of these practices was in sight. Parochial incumbents were supposed to be

priests and the crown ensured the effectiveness of a parish system by enforcing

the payment of teinds or tithes, the tax of 10 per cent of the annual increase

of domesticated plants (corn, hay etc.) and animals. Already by the middle of

David I’s reign the pope’s commands were being taken seriously by clergy and

laity; by the 1160s Scottish bishops were being appointed papal legates; and

in 1192,bythe bull of Celestine III known as Cum universi Christi, the entire

Scottish church (save for the diocese of Galloway, attached by ancient tradition

to York) was uniquely made the ‘special daughter’ of the Roman see, with no

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the twelfth century 593

ecclesiastical authority holding an intermediate role between the pope and the

Scottish bishops.

Dramatic as these changes were – and they amounted to nothing less than

the gathering of isolated Scottish Christianity within the fold of the papal-

dominated western Catholic church – they probably came second in the popu-

lar mind to the introduction of Benedictine monasticism and other continental

forms of conventual life. This was overwhelmingly the work of the monar-

chy, inspired by the example of Queen Margaret who had brought the first

Benedictine monks to Scotland, from the cathedral monastery of Canterbury,

in the 1080s. The church she founded at Dunfermline, which became an abbey

in 1128, was the inspiration rather than the model for the religious communi-

ties established by Margaret’s sons Alexander I and especially David I. They

favoured newer ‘reformed’ orders such as the Augustinians, Tironensians and

Cistercians, and by the end of Malcolm IV’s reign (1165)ascore of monasteries

had been founded by the crown and a few great magnates from the English

border to the Moray Firth. Monks and canons regular acquired vast landed

estates and applied advanced techniques to their management and exploita-

tion. Arable cultivation, fisheries and the production of salt and coal were all

given a powerful boost by monastic enterprise. But what the Cistercians of

Melrose and Newbattle, the Tironensians of Kelso and the Augustinians of

Jedburgh and Holyrood especially excelled in was the breeding and rearing

of sheep whose fleeces were of sufficient quality to sell to advantage on the

Flemish market.

It can hardly be doubted that twelfth-century Scotland gained in peace and

stability from the good fortune of a largely undisputed succession of strong

kings. The shocks and strains consequent upon the Norman Conquest of

England were cushioned by the native Scottish dynasty, and more profoundly

it may be argued that the heterogeneity of Scotland even before the Norman

advent made it easier, not harder, for the dynasty to encourage so much drastic

innovation and at the same time keep its sights fixed steadily on the target of

a unified regnum Scotorum.However strange it may seem, William the Lion

died in the odour of sanctity. Thirty-five years later the canonization of his

great-grandmother Margaret set the seal of religious respectability upon the

labours of the twelfth-century monarchy.

wales

In many fundamental respects, Wales resembled Scotland. Innumerable kin-

dred groups governed by agnatic relationships composed the dominant class

to which the words ‘free’ and ‘noble’ could be applied indistinguishably. Along

with their slaves and dependent peasantry or bondmen, the communities of

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

594 geoffrey barrow

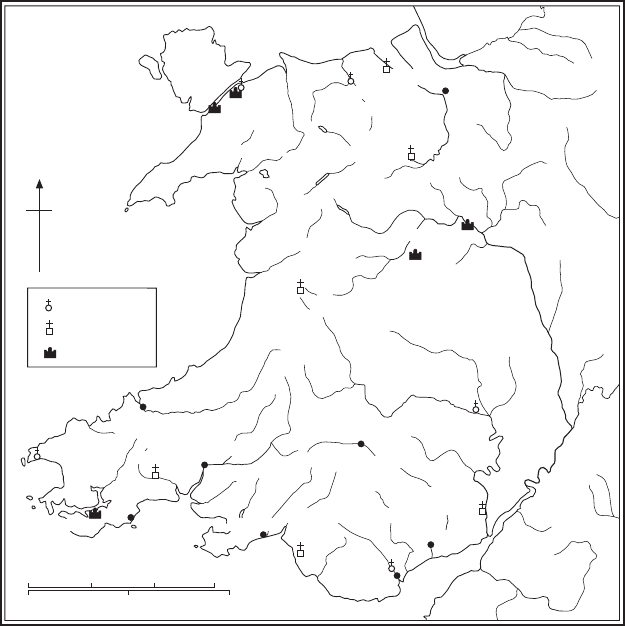

0255075 km

0 50 miles25

N

Hereford

Newport

Cardiff

Basingwerk

Dee

Tintern

Llandaff

St David's

Pembroke

Tenby

Carmarthen

Gower

Swansea

Whitland

Margam

Bangor

Caernarfon

Shrewsbury

Severn

Dee

S

e

v

e

r

n

Teifi

St Asaph

Brecon

BRECKNOCK

Chester

POWYS

BRYCHEINIOG

MEIRIONYDD

GWYNEDD

ANGLESEY

C

E

R

E

D

I

G

I

O

N

C

A

R

D

I

G

A

N

D

E

H

E

U

B

A

R

T

H

D

Y

F

E

D

GLAMORGAN

GWENT

S

e

v

e

r

n

FOUR

CANTREDS

Bishoprics

Monasteries

Castles

Cardigan

Montgomery

Valle

Crucis

Strata

Florida

Map 14 Wales

free kindreds lived in scattered townships established across the limited areas

of lowland plain (Anglesey, Glamorgan and parts of the south-western penin-

sula) and in the sheltered valleys of the hillier or mountainous country which

made up the rest of Wales. The typical basic unit of settlement was the tref

or homestead, usually consisting of a permanent nucleus of dwellings, byres, a

mill and perhaps a chapel sited on lower or sheltered ground, where humans

and stock would over-winter, together with an area of upland grazing occu-

pied, especially by women, children and older men, in the summer months

so that cattle, sheep and pigs could get the fullest benefit of the short growing

season for hill grass. The permanent valley settlement was the hendref (‘old

homestead’), while the hill shieling, where structures for habitation might be

temporary, was called hafod or hafoty.Alarger unit, implying lordship over

free and unfree was the maenol or maenor, composed of around a dozen trefi,

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the twelfth century 595

while a dozen maenolau would make up a cantref (Anglicized as cantred), the

standard district throughout most of Wales for the purposes of royal or princely

government. In the twelfth century, however, Wales did not form, and indeed

never had formed, a single kingdom. Wales, after all, was simply the largest

area (others were English and Scottish Cumbria and Cornwall) from which the

Anglo-Saxon invaders of the fifth and sixth centuries had failed to dislodge and

supplant the existing Brittonic population. The Welsh were acutely conscious

of constituting, with a few other groups, the last of the Britons, preserving and

handing down traditions of Christianity and even of romanitas which long an-

tedated the culture of the barbarian and hated Saeson or Saxon. But in reality

there was nothing in Wales of romanitas save the surviving remains of Roman

fortresses, towns and roads.

It is conceivable that in one or two places (e.g. Old Carmarthen, east of the

medieval borough) the site of a Roman town had continued as a place for trade

or seasonal fairs. But in general the organization of Welsh society was hostile

to the formation of genuinely urban communities. Such settlements, formally

definable as boroughs, inhabited by burgesses enjoying trading privileges and

the protection afforded by a castle and perhaps an earthwork or stone enceinte,

can only be seen to emerge in Wales from the end of the eleventh century. They

were the work of ‘English’ invaders and colonizers, and for long were regarded

with suspicion and even hatred by the Welsh, even though in periods of peace

they took advantage of the trading opportunities provided. Thus in the south

such boroughs as Brecon and Newport, both on the River Usk, Cardiff on the

Taff, Swansea on the Tawe, Carmarthen on the Tywi and (probably) Tenby

came into being through the deliberate planning of incoming Anglo-Norman

feudatories such as Braose, fitz Hamo, Beaumont or Clare. The urban element

in twelfth-century Wales should not be underestimated, although for long the

boroughs remained small, inward-looking and markedly on the defensive.

The Welsh, united culturally by their use of a P-Celtic version of the com-

mon Celtic family of languages, were a pastoral people organized in clans, recog-

nizing the superior chiefship or lordship of a number of warring dynasties each

of which would claim the right to provide a king or prince over a distinct gwlad

(‘country’), a term difficult to define but most easily understood when applied

to the best-known and longest enduring of such territories, Mon (Anglesey),

Gwynedd, Powys, Brycheiniog (Brecknock), Morgannwg (Glamorgan),

Ceredigion (Cardigan) and Dyfed. These geographical divisions reflected the

fact that Wales is composed of big mountain massifs, hill plateaux and spiny

ridges intersected by many river valleys and long tidal estuaries. A ruler power-

ful enough to command a gwlad or group of gwladoedd in the north – Anglesey,

Gwynedd and the ‘Four Cantreds’ further east, for example – could seldom

hope to assert any permanent lordship over the south of Wales, with which his

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

596 geoffrey barrow

lines of communication were very poor. And vice versa: a warlord dynasty might

rise to power in Deheubarth (‘the southern part’) but could make no impres-

sion on the north. The most that northern or southern princes could normally

hope to achieve was to exert control over the middle countries of Meirionydd,

Ceredigion or Powys, and for this control they were frequently rivals.

Toamuch greater degree than Scotland, Wales had felt the impact of

the Norman invasion of England. Within ten years of the battle of Hastings

Norman warriors had established powerful lordships and built massive castles

along the uncertain border between Wales and England and had penetrated

far into indisputably Welsh territory. By 1102, the three buffer-states created

by William the Conqueror to guard against Welsh attacks – and also as spring-

boards from which a Norman advance into Wales could be launched – had been

reduced to one: Hereford and Shrewsbury had been eliminated, leaving only

Chester as the principal bastion of English royal aggression. On the southern

march of Wales, in Gwent and Glamorgan, lesser barons and feudatories held

lordships below the level of earldom, and pushed on steadily and unobtrusively

with foreign settlement. Robert fitz Hamo laid claim to Glamorgan, Bernard

of Neufmarch

´

etoBrycheiniog, and Gilbert fitz Richard of Clare to Ceredigion

far in the west. In mid-Wales the lesser followers of the great family of

Montgomery, disgraced and dispossessed in 1102, held fast to their frontier cast-

leries and penetrated into Welsh cantreds on the upper Severn and Dee. From

Chester Hugh of Avranches (d. 1101) followed up the pioneering conquests

of his cousin Robert ‘of Rhuddlan’ and built castles as far west as Bangor and

Caernarfon. At the outset of the twelfth century it must have seemed that Wales

was poised on the brink of a thoroughgoing and permanent Norman conquest.

It was not to be. In some ways the twelfth century may be seen as an

heroic age for Wales, and in respect of cultural and national identity it was

unquestionably an age of great achievements. At least three Welsh rulers of the

century, Gruffydd ap Cynan and his son Owain (Owain Gwynedd) in north

Wales and Rhys ap Gruffydd (usually known as the Lord Rhys) in the south,

achieved a measure of independence vis-

`

a-vis English kings and Anglo-Norman

marcher lords. Their kingly status was admittedly not to be compared with

that of Henry I or Henry II, or even with the status of the kings of Scots in

this period. Yet the ascendancy they established in Gwynedd and Deheubarth

pointed the way for the more spectacular achievements of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth

(‘the Great’) and Llywelyn ap Gruffydd in the thirteenth century. At the very

least they made it clear that in the absence of notable advances in technology

no English conquest of Wales would succeed without a massive concentration

of energy and resources.

Although Henry I spent much time and effort in order to assert his authority

over the border lordships initiated by his father and over the Welsh princes,

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the twelfth century 597

he achieved little more than an uneasy peace. The fall of the house of Bellˆeme

or Montgomery in 1102 created a dangerous vacuum in mid-Wales (Powys)

which was filled partly by the promotion of the native ruling dynasty to a short-

lived ascendancy, partly by appointing an able Norman administrator, Richard

of Belmeis, as, in effect, warden of the Middle March – supported, rather

oddly, by appointment as bishop of London. In southern Wales English power

was exerted even more effectively, partly because of the persistent pressure

of Anglo-Norman, Flemish and Breton adventurers, partly because Henry I

took care to appoint men of outstanding military ability such as Gerald of

Windsor to key positions, among which was the custody of Pembroke Castle,

first built by Arnulf of Montgomery in the later eleventh century. On the

west coast, the gwlad of Ceredigion was in 1110 bestowed by the English king

upon Gilbert fitz Richard of Clare, who proceeded to allocate the constituent

cantreds to ‘Norman’ followers, each securing his position as settler in hostile

territory by building his own castle. Gilbert himself built the earliest motte-

type fortresses near Llanbadarn (Tanycastell, south of Aberystwyth) and at Din

Geraint (Cardigan), at the mouth of the Teifi. He was succeeded in 1117 by his

son Richard who held Ceredigion until the death of Henry I prompted the

most successful Welsh revolt since 1094.

Even a strong king such as Henry I could not impose calm upon the Welsh

situation for more than a few months at a time. In 1114 Henry found it necessary

to lead an expedition to north Wales where Gruffydd ap Cynan, scion of the

ancient dynasty of Rhodri Mawr (d. 878), was steadily building up a kingship

to rival that of his great eleventh-century namesake Gruffydd ap Llywelyn. The

English king himself advanced through Powys while the earl of Chester and

Alexander I of Scotland (clearly acting on this occasion as Henry’s vassal) led a

force along the northern coastal route. Although there were no open hostilities,

the Welsh rulers submitted and Gruffydd was forced to pay a heavy fine to be

restored to Henry I’s peace. Seven years later Henry again invaded mid-Wales

and subdued Maredudd ap Bleddyn upon whom the English king imposed

the severe penalty of 10,000 head of cattle. By dint of maintaining peaceable

relations with the English crown while at the same time taking advantage of

strife and rivalries among the neighbouring Welsh rulers, Gruffydd, who died

in 1137, was able to hand over a substantially enlarged kingdom of Gwynedd to

his heirs, especially to his eldest son Owain, known simply (to distinguish him

from a contemporary prince of Powys of the same name) as Owain Gwynedd.

The English (by 1135 it makes little sense to call them ‘Normans’ or even

‘Anglo-Normans’) seem to have been completely unprepared for what hap-

pened in Wales as soon as the news came of Henry I’s death. On New Year’s

day 1136 a native prince from Brycheiniog inflicted a startling defeat upon the

English settlers in Gower. This was a signal for a general uprising. The ruler of

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

598 geoffrey barrow

Deheubarth, Gruffydd ap Rhys, appealed to Gwynedd for aid to rid the south

of foreign oppressors. Richard fitz Gilbert lord of Ceredigion was slain in am-

bush and the forces of Gwynedd over-ran Richard’s lordship and razed the

castles of himself and his supporters. Stimulated by these successes the Welsh

from almost every gwlad joined the revolt. The decisive engagement took place

at Crug Mawr north of Cardigan early in October. A well-armed English army

recruited from south Wales and led by the sons of Gerald of Windsor was

routed with great slaughter by the native levies under Owain Gwynedd. Inept

fumbling by Stephen and those he deputed to restore English royal authority

allowed the Welsh to consolidate the gains they had made. Gruffydd ap Rhys

died in 1137 leaving young sons. In consequence the initiative passed to Owain

Gwynedd who took Ceredigion into a northern ambit. From north to south

the marcher lords who represented the front line of English settlement fell

back, losing castles and territory. The outbreak of war in England towards the

end of 1139 did not complicate matters as much as might have been expected.

Most of the marcher lords took their cue from the most powerful magnate

among them, Robert earl of Gloucester, who was the Empress Matilda’s half-

brother and principal supporter. In the later 1140s there had been some modest

recovery of English positions, especially in the middle marches and in Dyfed

(the region around Carmarthen). But by and large a revived Welsh ascendancy,

under the aegis of Owain Gwynedd, prevailed throughout much of Wales –

save for Glamorgan and the south-east – until the early years of Henry II’s

reign.

In some respects the spirit of independence which swept through the Welsh

ruling classes in 1136 also took hold among the clergy. Claims were put forward

vigorously in the 1140s for St David’s, the oldest of the Welsh bishoprics and

the principal church of south-west Wales, to be recognized by the papacy as

metropolitan, on a footing of equality with Canterbury and York. The efforts

of Bishop Bernard (1115–48) failed, but claims for Demetian primacy were to

be revived at the end of the twelfth century by Gerald of Wales (Giraldus

Cambrensis), a direct descendant of Gerald of Windsor. Welshmen were ap-

pointed as bishops in the dioceses of Bangor and even Llandaff, but the newly

created see of St Asaph, serving north-east Wales, may be seen as a deliber-

ate extension of English influence. The Cistercian Order took root in Wales

during the period when national revival was at its height. Although several of

the Order’s houses, for example Tintern, founded from L’Aumˆone as early as

1131,orBasingwerk (also 1131 and originally Savignac), were always very closely

under marcher influence, many others, especially the family branching out

from Whitland (1140), a daughter house of Clairvaux, quickly became iden-

tified with Welsh culture and aspirations. The family of Whitland was the

most widely ramified throughout Wales, offshoots being established at Cwm

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the twelfth century 599

Hir, Strata Florida, Strata Marcella, Cymer, Llantarnam, Aberconwy and Valle

Crucis, while Margam (1147) was Whitland’s sister house.

The second half of the twelfth century saw the establishment of a north

Welsh dominance which was to persist until the overthrow of independent

Welsh rule in the later thirteenth century. The pre-eminence of the southern

prince Rhys ap Gruffydd (‘the Lord Rhys’) from 1170 to 1197 may appear

to contradict this statement. Rhys’s power, however, was personal and owed

much to the trust placed in him by Henry II. After his death the marcher

lords were able to reassert their domination of Gwent, Glamorgan, Gower and

Pembroke. In so far as Welsh national aspirations had a focus it was to be found

in Gwynedd and specifically in the dynasty of Gruffydd ap Cynan.

Northern Welsh power had been built up during the ‘Anarchy’, helped by

avacillating English king and an earl of Chester far more interested in his

English ambitions than in his Welsh frontier. With Henry of Anjou firmly in

the saddle Owain Gwynedd was forced to adopt a different strategy. It is true

that the English royal expedition against him in 1157 went badly wrong, but

Owain prudently did homage, surrendered hostages and, more seriously, gave

up his control of Tegeingl (Flint). Henry’s next attempt to assert English author-

ity in Wales, in 1163, was directed against mid- and south Wales. By 1155, one

son alone, Rhys, survived of the offspring of Gruffydd ap Rhys of Dyfed, and

he had succeeded in expanding the lordship of southern Wales until it reached

from the Bristol Channel to the River Dovey. But in 1158 he had accepted

English overlordship and surrendered much conquered territory, including

Ceredigion which was reclaimed by the house of Clare. In 1163 Henry advanced

through south Wales to the borders of Ceredigion where Rhys ap Gruffydd

submitted and was led into England virtually as Henry’s prisoner. In July he did

homage to Henry at Woodstock, along with Owain of Gwynedd and Malcolm

IV of Scotland. The long quarrel between Henry and Thomas Becket allowed

the Welsh to throw off Angevin control. In 1165 Gwynedd and Deheubarth

combined in a full-scale revolt against crown and marcher lords alike. Henry

II’s army entered Wales in early August north of the Severn valley and struck

westward towards the Berwyn range. The weather proved appalling, the heav-

ily armed horse and more lightly equipped infantry floundered in impassable

bogs and ran perilously short of food. The king withdrew with his host to

Shrewsbury and never again attempted to subdue the Welsh by military force.

Until his death in 1170 Owain Gwynedd pursued a statesmanlike policy,

acknowledging Angevin overlordship yet keeping it at a distance by refusing

to carry out provocative strikes against the English crown or sensitive marcher

baronies. The full measure of his achievement was only to show itself at the end

of the century, when his grandson Llywelyn ab Iorwerth (‘Llywelyn the Great’)

successfully asserted his claim to rule over the enlarged Gwynedd built up by

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

600 geoffrey barrow

Owain and went on to create the closest approximation to a native kingdom of

Wales which there was ever to be. For almost thirty years after Owain’s death,

however, ascendancy among the Welsh passed to the south. In the later 1160s

Rhys ap Gruffydd was shrewd enough to take full advantage of the situation

unfolding in Ireland. The king of Leinster’s appeal to Henry II for military help

against his Irish enemies opened the way for many marcher lords in southern

Wales to try their luck across the sea. They hoped to compensate themselves for

the loss of territory they had suffered in Wales since the beginning of Stephen’s

reign. For his part Henry II was content to make an apparently loyal Rhys

the English crown’s chief supporter in south Wales. On his way to Ireland in

autumn 1171 Henry confirmed Rhys in possession of the extensive territories

(especially Ceredigion) which the Welsh had recovered in 1165.Onhis return to

Britain, in 1172,heappointed Rhys ‘justiciar of south Wales’ effectively placing

him in charge of all the lesser princes of Deheubarth. The Lord Rhys repaid the

king’s favour by supporting him loyally in the great rebellion of 1173–4. The

relative peacefulness of Wales was demonstrated at Christmas 1176 when an

eisteddfod was held at Rhys’s newly built castle at Aberteifi (Cardigan) to which

poets, singers and musicians were invited not only from Wales but also from

England, Scotland and Ireland. Rhys’s ascendancy was to last for another two

decades, but his last years were darkened by strife among his own sons and by a

marked deterioration in his relations with the English crown. Nevertheless, it

has to be said that in Wales, scarcely less than in Scotland, the twelfth century

saw the arrest, and in some important ways the reversal, of a major historical

process. From 1066 individuals and families of continental (especially Norman)

origin had penetrated far into the island of Britain, acquiring kingship, lordship

and land. From 1169 they were to repeat the process in Ireland. In Scotland

the development of a strong feudally organized kingdom had retarded and

radically modified this process. In Wales a succession of outstandingly able

native rulers, supported by a powerful and articulate resurgence of national

feeling and culture, had likewise been able to apply a brake to the ‘Norman’

tide. The result was to be two countries, marcher Wales and Welsh Wales ( pura

Wallia), producing consequences which have lasted to our own times.

ireland

In Irish history the twelfth century must always be the age of conquest, the mo-

mentous turning-point when English adventurers, mostly belonging to families

of Norman, Flemish, Breton or other continental background, exploited their

military skills and techniques to acquire kingdoms and trading towns in the

south of Ireland. Their freelance attempts gave the monarchy of Henry II the

opportunity, seized without delay, to assert an explicit claim to suzerainty in

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008