Lewin Benjamin (ed.) Genes IX

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

lzL

sVNU eprng fq

pepar16

aE uel 6u$!pl

VNU

II'lZ

ilxo

erql

yo

aruanbas

aql

01 elrlplJJ

UrqsJrueJJ

e seq uraloJd

1

lrunqns

espprxo aurorqro]zb

er{1

Jo

aruanbas

Jqt

'pJJJAoJsrp

eq ot

JSef,

tsJrJ

Jql uI

'eupuoq)olrrrr

JrrrosouedL4;o

saua8

IeraAJS

yo

spnpord aqt ur a)uJnbas ur sa8ueqr

JrlerupJp Lq

papanar

sr Surlrpa

yo

ad,{1 JJqlouV

'ase6q

yp1

pue

'r{1mr1re

asere;suer11r{pr.ln

leululal

'aspallnuopua

1o

xalduor

e

r\q pazr{1e1er st 6ur1Lp3

o

'saulpun

1o

(uoqelep

'ua4o

ssal

to)

uorlr.ppe

ro;

a1e1due1 aq1 sapLnord

ypg

aprnb

eq1

o

'pa1pa

aq o1 uorbar oql

Jo

sapts

qloq

uo

ypg

eprn6 e

qluu

srred aspq

VNU

alerlsQns

e{f

r

'outpun

Jo

suoqalap.lo suoqJasur [q srnrro eupuoq]oltul

auosouedfi.r1 ur 6urlrpa

![!

aAtsua]xl r

svNU aplng

fiq

paparr6

aB uPl

6u!}tpl

vtrtu

'seleJlsqns

Jleql uI

.dtr;gtrads

aruanbas

JoJ

tuaruJrrnbar;o

sadfu

luaJaJJIp

J^eq

,{eru

sruals,{.s Surtrpa

lueJeJJrp

snql'uorttuSolar

rqoads ro1 zi:essarau sr uo6ar

xaldnp arp uIqlIM

Surrredsrru

Jo

uratted

v'uoJlur

rupansumop

aql

ur aluanbas ,{reluauralduroJ e

pup

uoxe

Jql uI

uor8ar

petpa

aql uJJMlJq

peuroJ

s1 atys

ta8rer

Jql

Jo

uopgSorar ro;

Lressarau sI

teqt

uor8ar

parred-aseq

e

'vNg

S-UnlC

er{t

Io

aseJ

aql

q

lpql

sMoqs

#ts"J.d *'it{'l*Ji

'le8Jel

IUJIJIJJnS

e sapnord

alts

Surlrpa aql Surpunorrns

(saseq

9g-)

aruanbas

gerus

.{lanrlplal

e

teqt

slsaSSns

luana

Sutltpa

g-ode

aqt

ro; rua1s,{.s oJitr ul ue

;o

tuarudolenep

aq1

'aruanbes

JprloalJnu e azruSorar

,{lnarlp

plnor

Jo

'sarudzua

SurLyrporu-yNgt

01 snoSo

-leue

rJuueur e ur eJnlf,nJls

Lrepuoras

yo

uor3ar

relnrrued e azruSolar Leru xaldruoJ

eqJ

'y1qg

roldarJr

uruol

-oJ3S

P Ur JnJJO S1UJAJ

relrurs

pue

'YNU

JOl

-dara:

aleruetnlS Jql

q

salrs

la8ret

Jql sJZIU

'uorbar

xaldnp

yp6

parred

l{lpayadur up ur auruapp

up uo sltp

aseu

-rurPop

P uoqM slnrlo

vNUru

to

6uL1rp3

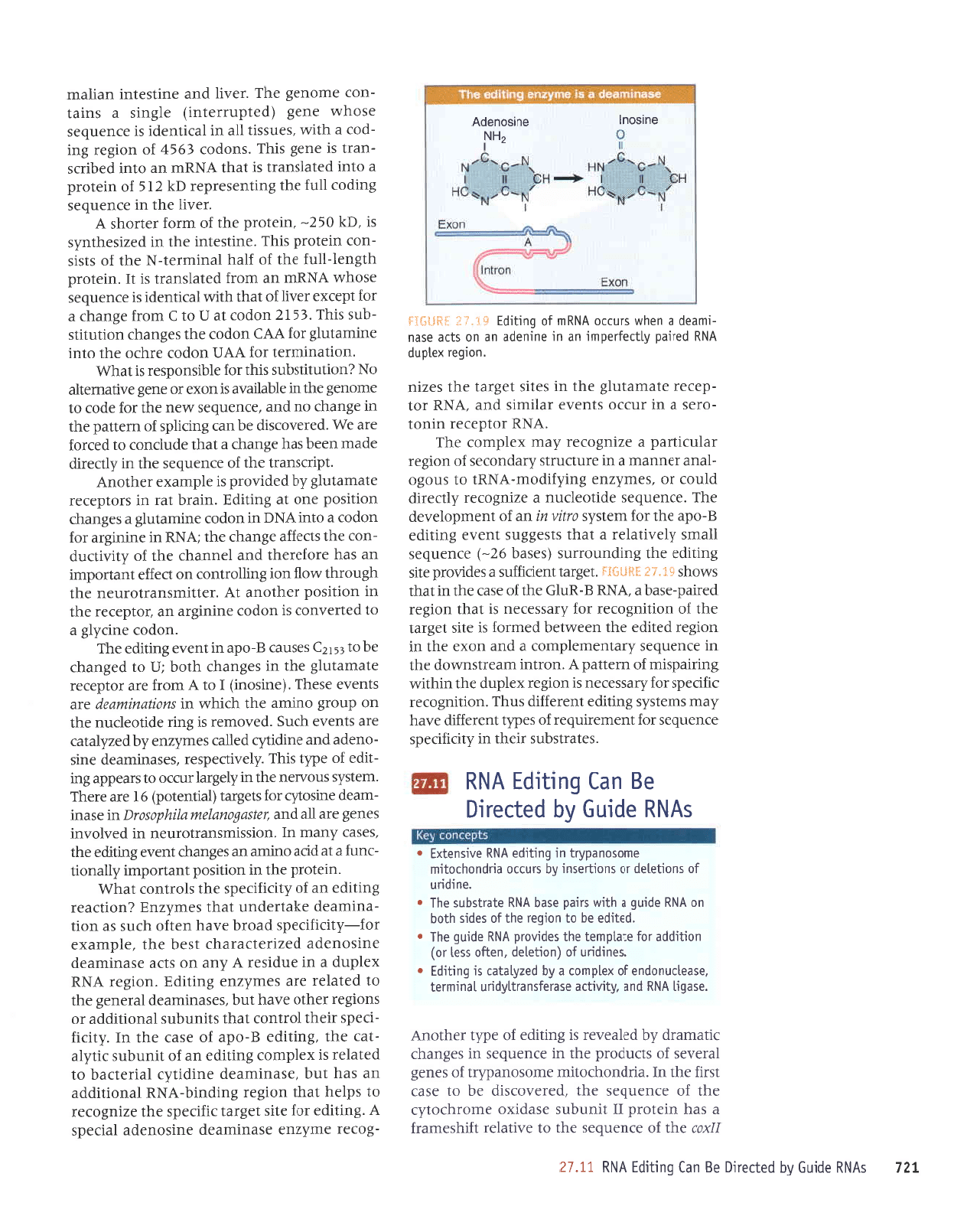

6'r-.14 *Hfi*Ec

-3orar

arur{zua

Jseulrupap

JuISouepP

lenads

y

'3ur1rpa

roJ J1IS

la8:el

rtyrads

aql aztuSolar

o1 sdlaq

lBql

uot8ar

Sutputq-ypg

leuolltppe

ue seq

tnq

'aseulueap

aurptlr{J

IPIJJDeq

ol

peleleJ

sr

xaldtuor SuIlIpa

ue

Jo

llunqns

lrtz(1e

-teJ

Jql

'3ur1rpa

g-ode

Jo

asp)

eqt uI

'^tpIJ

-nads

rraql

IoJtuoJ

lpqt

slpnqns

IPuoIlIppP

Jo

suorEar

raqto

elpq

]nq'ses€ulueap

prauaE

aq1

01

patplar are saru.{.zua

Sulrlpg

'uor8ar

ygg

xaldnp

e uI enplsJr

y

due uo sl)e

Jseulureap

Jursouapp

pezrJatf,erpqJ

rsaq

aql

'aldruexa

;oy-d1nr;trads

peorq JApq ualJo

qJns

se uoll

-Purlueap

J>lPuapun

leqt

seru,{zug

zuol}f,eJJ

Surlrpa

ue;o

z{ltrqtrads

aqt

sloJluo)

teqM

'uralord

Jq1 ut

uolllsod

lueuodrur

z(1euop

-)unJ

e

le

pDp

ourure

up saEueqt

luaura

Sql1pa aql

'saser

Lueru

uI

'uolsslursueJlornau

uI

pJAIoAUI

saua8

a.re

[e

pue

'ta1su6oua7aw

ap4dosotq

ur aseur

-ueep

arnsoft

roy sta3rur

(ppualod)

91

ale Jreql

'rualsk

snoAJJu

eql

rn,{.1a8re1rrnro

ol

sreadde 3rn

-llpa

Jo

ad,{1 srql

,{.1a.nuradsar

'sJseulureep

auIS

-ouape

pue

aurpp,{r

palpr

saru,{zua,{q

paz,{prer

aJe slualJ

q)ns

'pe^ouar

sr Surr

Jppoapnu

eql

uo dnor8

oulure

Jql

qllqM

ur

sultloutuffiap

Jte

sluJAJ

asaql

'(aursour)

1

or

v

uorJ

a:B roldarar

aleurelnlS

eqt

ul saSueqt

qloq 1n

ot

pa8ueqr

aq

01

€EIzJ

sJsnpf,

g-ode

ur

lua,ra

Suntpa

"qJ-

--

'uopo)

JurJAIb e

01

pauJluoJ

sI

uopoJ

aurur8re

uP toldelJJ

eql

ur

uoplsod

Jer{toue

lV

'rJlllursueJloJneu

aql

qSnorqt,r,tog uot 8ut11o:luol

uo

peJJJ

lueuodrut

ue sPq eJoJeJaql

puP

IJuueqJ

:ql

;o

,(lr.tr1;np

-uo)

aq1 sDaJJe

a8ueqr

aql

IYNU ut

aurut3re

ro;

uopor

e otul

VNo

ul uopoJ

aunue1n13

e

sa8ueql

uoltrsod

auo

le

Sutrpg

'uIPJq

lPJ

ut sroldarar

ateurelnp

u(q

papr,lord

st aldruexa

JeqlouY

'ldtnsuerl

aql

Jo

JJuJnbas

aqt

ur ,{prarp

appur

uaeq

seq a8ueq;

p

lPqt

apnlJuo)

ol

peJJoJ

JJe e1,1

'pareloJslp

eq

uPJ Suortds;o

uralled aq]

ur a8ueqr

ou

pup

'atuanbas

,lrau

eql roJ apoJ

01

aruouaS

aql

rn alqelle^e

sI

uoxa ro

auaS anuerrrJ{e

oN

Zuountpsqns

slqr

roJ alqtsuodsar

q

lPqM

'uorleurrural

JoJ

wo

uopoJ

aJqJo

aq1 otul

aururelnlS

ro;

yy)

uopo)

aqt sa8ueqr

uonnllls

-qns

srqJ'€EIz

uopol

le

|l

01

)

IxorJ

aSueql

e

ro;

]datxa

JJAIT

Jo

teql

qll

^

IeJIluJpI

sI J)uJnbes

JsoqM

VNUrx

ue uroJJ

pelelsueJl

sl

U

'ulalord

qr3ua1-11ny aql

Jo

JIeq

l€ulurel-N

eqr

Jo

slsls

-uor

uralord

sIqJ

'eullselut

eql

ut

paztsaqlur(s

sl

'(I

gEZ-

'utatord

JI{t

Jo

IrrJoJ

Jauoqs

Y

_

'Je^rl

eql

uI eJuanDJS

Surpor

ilnJ

aql

Suuuasardar

q1{

Z

I

g

1o

utalord

e o1ul

pelPlsuPrl sI

leql

VNUIU

uP

olul

paqlrJs

-upr1

sI aua8

srql

'suopoJ

f.9SV

lo

uor8ar 3ut

-poJ

e

qlllvt

'sanssll

IIP

uI

IeJlluJpl

sl JJUJnbJS

JSoqm

aua8

(pardn;ra1ut) a13uts

e

sulel

-uol

JrrrouJ8

aql

'rarrg

pue eullsatul

ueIIPur

tur'j

eursoul

oulsouapv

gene.

The

sequences of the

gene

andprotein

given

in

iii,i:*l

:.;.**

are

conserved in

several try-

panosome

species. How

does this

gene

function?

The

coxll mRNA

has an insert

of an addi-

tional four

nucleotides

(all

uridines)

around the

site of frameshift.

The insertion

restores

the

proper

reading

frame;

it inserts

an extra amino

acid

and changes

the amino

acids on either

side.

No second

gene

with this

sequence can

be dis-

covered, and

we are forced

to conclude

that the

extra

bases are inserted

during

or after transcrip-

tion.

A similar

discrepancy

between nRNA

and

genomic

sequences is found

in

genes

of the SV5

and measles paramyxoviruses,

in these

cases

involving

the

addition of G residues

in

the

mRNA.

Similar

editing of RNA

sequences

occurs

for

other

genes,

and includes

deletions as

well

as additions

of uridine. The

extraordinary

case

of the coxIII

gene

of Trypanosoma

brucei is sum-

marized

in

ai*:iRl

iI.I:.

More than

half of

the residues

in the wRNA

con-

sist of uridines

that

are not coded

in the

gene

Com-

parison

between

the

genomic

DNA

and the

mRNA

shows

that no stretch

longer

than seven

nucleotides

is represented

in

the mRNA

with-

out alteration,

and runs

of

uridine up

to seven

bases long

are inserted.

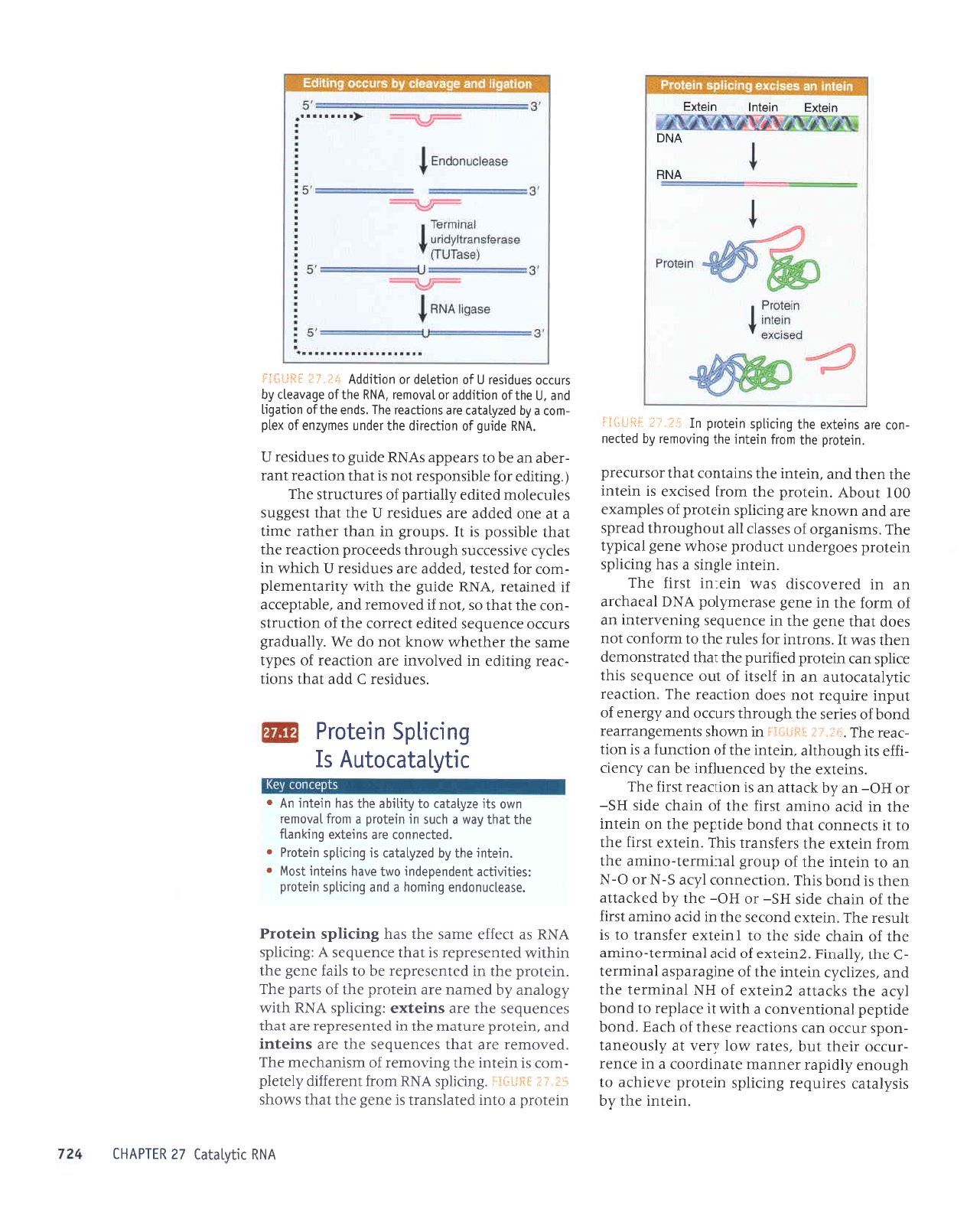

What provides

the information

for

the spe-

cific insertion

of

uridines? A

guide

RNA

con-

tains

a sequence

that is complementary

to the

correctly

edited

mRNA.

l'i*ijFlt

i,r.ii-i

shows a

model for its

action in the cytochrome

b

gene

of

Leishmania.

The sequence at

the top of the figure

shows

the original transcript,

or

preedited

RNA.

Gaps

show

where

bases will be inserted

in the

edit-

ing

process.

Eight uridines

must be inserted

into

this region to

create the valid mRNA

sequence.

The

guide

RNA is complementary

to the

mRNA for

a significant distance,

including

and

surrounding the edited region.

T\zpically

the

com-

plementarity

is more

extensive

on the 3'side

of

the

edited region and is rather

shon

on the 5'side.

Pairing

between

the

guide

RNA

and the

preed-

ited RNA leaves

gaps

where

unpaired

A residues

in the

guide

RNA do not find

complements

in

the

preedited

RNA. The

guide

RNA

provides

a tem-

plate

that

allows the missing

U residues

to

be

inserted

at these

positions.

When

the reaction

is

completed

the

guide

RNA

separates

from

the

mRNA,

which becomes available

for

translation.

Specification of

the

final

edited

sequence

can be

quite

complex.

In this example,

a lengthy

stretch of

the transcript is

edited by

the insertion

of a total

of

l9

U residues,

which

appears

to

require

two

guide

RNAs

that act

at adjacent

sites.

The first

guide

RNA

pairs

at the

3'-most

site, and

the edited sequence

then becomes

a

substrate for

further

editing by the next

guide

RNA.

The

guide

RNAs

are encoded

as indepen-

dent transcription

units.

fg*LlFtfl

;,-:.i::

shows

a

map of the relevant

region

of

the Leishmania

r:'i:r-iii{

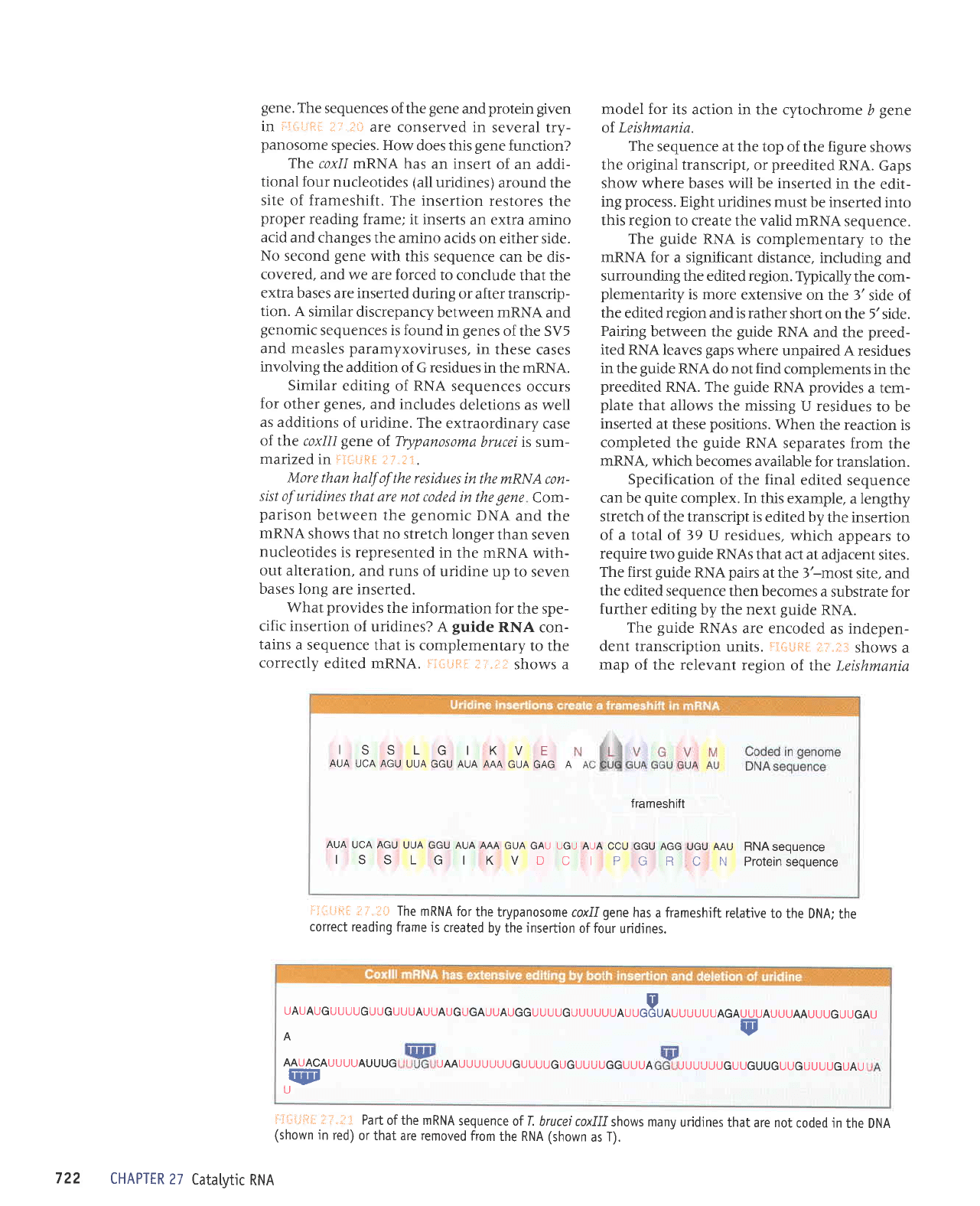

il,!li: The

mRNA for

the

trypanosome

coxll

gene

has

a

frameshift

retative

to

the DNA;

the

correct reading

frame is

created

by the insertion

of four

uridines.

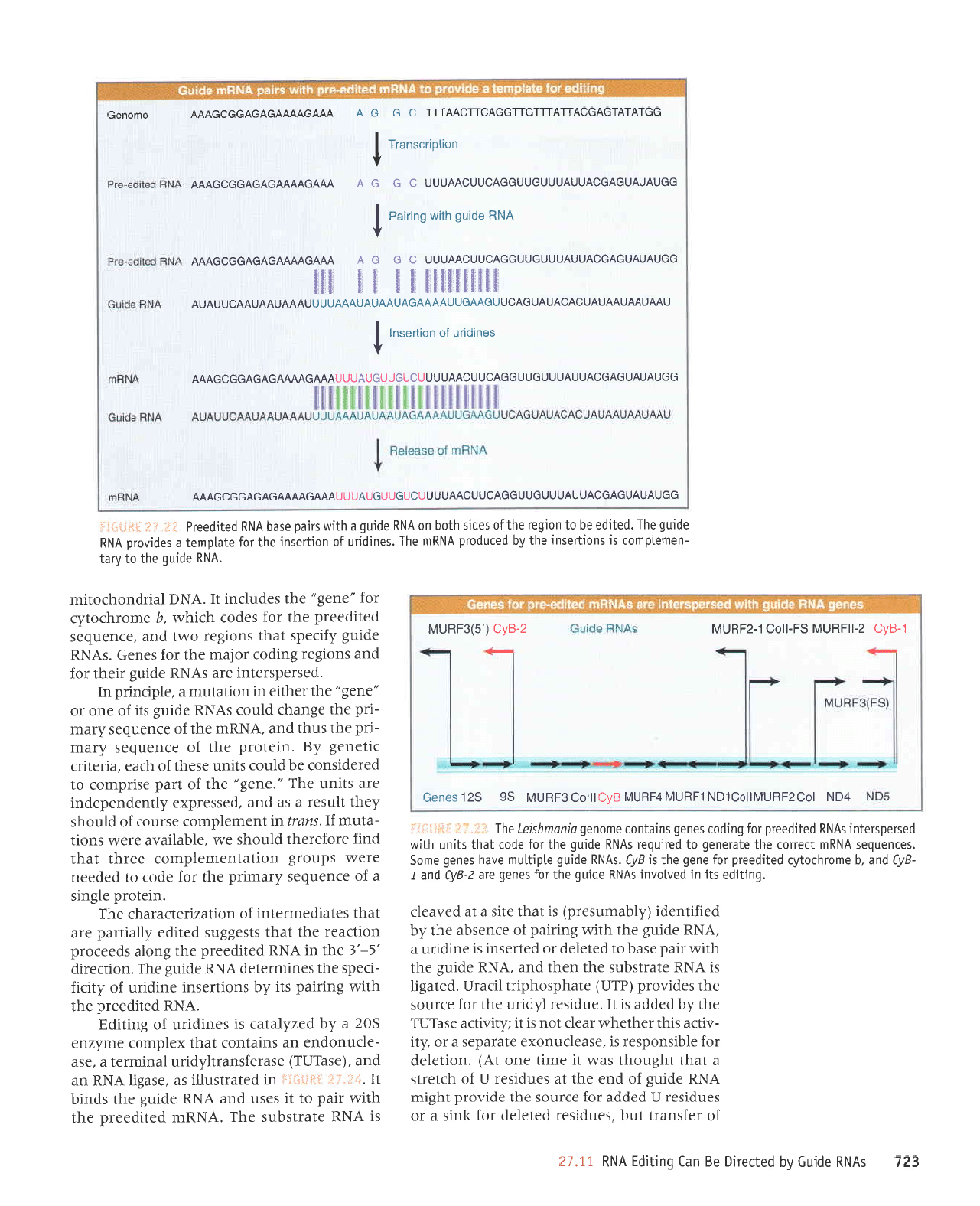

i;if;l.ifii;-:

rr

1'"1:1 Partof

themRNAsequence

of T.brucei

coxllf

showsmanyuridinesthatarenotcodedintheDNA

(shown

in

red)

or that are removed

from

the RNA

(shown

as

T).

ISSLGIKVE

AUA

UCA AGU

UUA GGU AUA

AAA GUA

GAG A

frameshift

AUA

UCA AGU

UUA GGU AUA

AAA GUA

GAU UGU AUA

CCU GGU AGG

UGU AAU

RNASEOUENCE

I

S S L

G I K V D

C I P

G R

C N Proternseouence

UAUAUGUUUUGUUGUUUAUUAUGUGAUUAUGGUUUUGUUUUUUAu,J,o,,,,,UAGAUUUAUUUAAUUUGUUGAU

A

AAUACAUUUUAUUUG

UAAUUUUUUUGUU

qEE

U

ru

UUGUGUUUUGGUUUA

UUUUUUGUUGUUGUUGUUUUGUAU

722

CHAPTER

27

Catatytic

RNA

EZL

sVNU aplng riq

paparr6

ag uel

6ulflpt

VNU

tI'lZ

Jo

JJJSuerl

lnq

'sanprsJJ

pJlalep

roJ >lurs

e ro

sanprsJJ

n

peppe

JoI J)Jnos aql apr.r.ord

rq8tu

y1qg

aprn8

Jo

pua

aqt

tp

sJnprsar

n

Jo

q)tals

e

tpql tq8noqr

seM

tr

Jurrt Juo

ty)

'uor1a1ap

roy

alqrsuodsJr sr

'Jseel)nuoxe

aleredas

e ro

Llt

-Arpe

srql JJqleqM JeJIJ

lou

sr

tr

:Ilr^rlJp

JSeJnI

aqt.{q

pappe

sl

tI

'enplser

1[prrn

Jqr JoJ

eJrnos

aqt sapno;d

(afn)

areqdsoqdrrl

prern

'pate311

sI

vNu

rtertsqns

Jqt uJql

pue

'vNu

aprn8

aql

qttl:red

eseq ol

pJlelep

Jo

pauJsur

sr

JurprJn

e

'y1..1g

aprn8 eqt

qtrm

SurrrBd

Jo

JJuJsqe

aqt r{q

pJrJrtuepr

(,{lqerunsard)

sl

teqt

Jtrs e

tp

pJ^palr

'6ur1Lpa

slr ur

po^lo^ur

sypX apLnb eq1 ro1 seuab

arc

7-9fi

pue

y

-g[j

pue'q

aurorqrolAr

palrpeard

rol

aueb aq1 s1

gfj

'sypX

aprnb a1dL11nu aneq

sauab

auo5

'seluanbas

VNUU

lrelor

aq1 elereueb

o1

perrnbar

sygX aprn6 aql lol apol

leql

slrun

qltM

pasradsrelursypgpalLpeerdrol

6urporsaua6sureluoreuouabDru?wqsLa].ogl_

l,l'r,:

1:tji!1,:ili

sl

vNu

alerlsqns aqJ

'YNutu

pallpeeJ0

Jql

qtp,r

rred 01

1r

sJsn

pue

YNU

aptnS

aqt sputq

1I

'r:,i]";..:l

:iiJi]l-11:i

uI

pJleJlsnl[

Se

'aseStl

vNu

uP

pue

'(ase1n1)

aseraysuenl.dpr.rn

IeuIIuJJl

e

'ase

-alJnuopua

ue suleluoJ

leql

xaldruor aruz{.zua

S0Z

e

Iq

paztrlewt sI seulplrn

;o

Sutltpg

'YNU

palparro

rql

qlpr,l Sur;red slr

Lq suoluasul

euIpIJn

;o

,{.1nt;

-nads

aql

sJuturJtrp

y1trg

aptn8 eqJ

'uopterlp

,s-,€

etfl ul

YNu

patrpaard

aql Suop

spaalord

uortleJr

Jqt

teqt

s1sa33ns

pJllpe .dlerued are

lPql

selelpJruJJluI

Jo

uollezlJelf,PJeqJ

eqI

'ura1o.rd

a13urs

e;o

aruanbas

.drerutrd

Jqt JoJ epoJ

ol

pJpaeu

a,raa,r sdnor8

uorleluarualdruot

eerqt

leq1

purJ

JJoleJJql

plnoqs J/!r

'elqelle^P

eJel!{ suoll

-plnru

lI'suau

ut

tuarualdruoJ

JSJnoJ

Jo

plnoqs

.daqt

11nsar

e

se

pue

'passardxa.dltuapuadaput

aJe slrun

aq1

,,'aua8,,

aql

Jo

lred

astrdruor

o1

psJeprsuoJ Jq

plnoJ

sllun JSJqI

JO

q)eJ

'PIJJIIJJ

rrtauaS

,(g

'ularord

eql

Jo

aruanbas

.,{.reru

-rrd

aqt snql

pup

'VNutu

Jql

Jo

JJuJnbas

ui.reut

-r,rd

aqt

a8ueqr

plnol

sVNU

aptn8

slt

Jo

euo Jo

,,aua?,,

JI{t

JJqlIa ul uollPlnlu

P

'aldnurrd

u1

'pasradsralul

Jre

syNU aprn8

rraql ro1

pue

suor8ar

3urpor

roleru

Jql JoJ

sJue5

'sVNU

aprn8

d;oads

leqt

suorSal

o,rtl

pue

'aruanbas

parpaard

aqt

roJ sJpoJ

qJIqM

'4

aruo.lqrolLr

ro;

,,aua8,,

aqt

sJpnlJul

tI

'VN11

Ielrpuoqlollu

'yp5

eprn6 aq1 o1

&e1

-uauralduor

sr suorlosur eq1 Aq

parnpotd

VNUur

aq1

'saurpun

Jo

uotilasut aq1

tol a1e1dLue1

e saptnord

yflg

aprnbeql'polrpaaqoluoLbaraqlJosaptsqloquoypXapLnEeqlrmsrLedaseqVNUpaltpoeld:li'l'it, Iil{:Lri:i

toN toczlunv{ilocf

oN HUnn

rlunu\

EASllloc elunt/\

s6

szt

sauae

t-s^c z-illHnu{

sJ-ltoc

t-zlunl/\

z-8^c

(,g)eJUnnl

eenvnvnevecvnnvnnn0n

noevcnncvvnnn

ncnen n0nvnn

nwvewwev9v99cevw

eenvnvnevecvnnvnnnenn

eevcnncwn

nn

ncnennenvnnnwvevwvevev00cewv

+

sourpun

1o

uotuesul

I

NWNWNWNVNCVCVNVNEVCNNEWENNVVVVEVNVVNVNVWNNNNVVVNVVNVVCNNVNV

flilf;fiilfriilfifltililf;frHfiil

9envnvnevocvnnvnnnenn9evcnncwnnn

3 3 e

v

vwewwevev99cewv

+

VNU

eplnb

qltlt

6uP;e3

|

egnvnvnevecvnnvnnnenne9vcnncwnnn

c e

e v

wveww9v9vecS9vvv

+

uotlducsuell

I

I

getvlvtevecvt-Lvlltel-]eevSl-tcvv-Ll-l

ce

e v

vwevwveveveeccvw

auouaS

'urJlur

JLII

^q

srs^lplpJ sJrrnbaJ

Suorlds

uratord

JAerqJe ol

q8noua

dlprder

-rJuueur

aleurprooJ

p

ur J)ue-r

-rnf,Jo

rrJqt

lnq

'salpt

.t,rol

Lra.L

le

.{1snoaue1

-uods

rnllo

uef,

suorlJpal

esJql

Jo

qteA

.puoq

JplldJd

IPuoIluaAuoJ

e

qll,11

1t

aleldar

ot

puoq

1'{re

aqf

s>lJelte

ZuretxJ

Jo

HN

IpuruJet

Jql

pue

'sazrpi{r

urelur

aql

1o

aurSeredse

leurrural

-)

aql Llleurg'Zurelxe

Jo

prJe

Ieururrel-ourrue

eql

Jo

ureqJ

aprs

Jql 01

IurelxJ

lJJSueJl

o1 sr

llnsJr

JqI

'urJlxJ

puof,Js

eql u

plf,p

ourue

lsJrJ

rql

Jo

urerlr

Jpls

HS-

ro

Ho-

aqr ,{q

pJ>lJelle

uar{t sr

puoq

srqJ

'uort)Juuo)

1,{re

5-p

ro

O-N

ue

ol uratur aql

1o

dnorS

lpu[uJel-oullue

eql

ruoJJ

urJlxa

aql sJJJSupJl

srql

'urelxJ

lsJrJ

aql

ot

tr

slJeuuoJ

leql

puoq

aprldJd

eqt

uo urJtur

eql ur

pr)e

ourue

lsrrJ

eq1

Io

ureqJ epls

HS-

ro

HO-

ue Lq

1re11e

ue sr uortJeal

tsrrJ

JqJ

'surJlxa

Jql

^q

pJJuJnlJur

eq upJ Lruao

-IJJa

sll

q8noqtle

'urJlur

Jql

Jo

uortJunJ

e sr uorl

-)eJJ

eqJ

'+l',:

i:

r,i*lil:;.

j

ur rruoqs

sluarua8uer.rear

puoq

Jo

sJrrJS

aqt

q8norqr

sJnJJo

pue

,{3raua yo

lndur

arrnbal

lou

seop

uorlf,pJJ

Jr{J

'uorlf,eJr

rrldlelerolnp

ue ur

JIJSIr

Jo

1no

aruanbas

srql

arr1ds uet

uralord

pagrrnd

aql

reql

peleJtsuorxap

uJql

sPM

1I

'SUOJlur

IOJ

SelnJ

aql o1 ruJoluoJ

lou

saop

leql

aua8 aqt

ur aruanbas

Suruanralur

ue

Io

ruJoJ

aql ur aua8

aseraru,i(1od

VNO

IeJeqJJp

ue ur

peJa^oJsrp

Se^l. urJlur

lsJrJ

JqJ

'urJtur

a13urs

e seq Sunrlds

uralord

sao8rapun

pnpord

JSoq,tr

aua8

lerrdz(1

aql'susrue8ro;o

sassep

1e

tnoq8norqt

peards

JJe

pue

u.lrou>l

a.re

Suoqds

uratord;o

saldruexa

00I

tnoqy

'uratord

aqt uoJJ pJSr)xJ

sr uratul

aql ueql

pue

'ulJlur

aql

sureluoJ

leql

rosrntard

'uLelord

aql

uo.lJ uralur

aql

burnouar r\q

papau

-uol

ale sutalxe

oql 6urcLlds

uralotd u1

!i.i

i _;iirit*i,j

vNu

lrl^lPlel

/z

ultdvHl

uleloJd

p

olur

pJlelsueJl

sr auaS aql

1eq]

sMoqs

*I'ir

$li**td

'SuDrIds

\/Nu

ruorJ

lurreJlrp

,{1a1a1d

-uroJ

sr urJlur

eqt Surnoruar

Jo

rrrsrueqJau

JqJ

'pa^oruer

ere

leql

saruanbas

Jqt Jrp sulelul

pue

'ura1o.rd

JJnleur

Jr{l ul

peluasa;dar

JJp

leql

saruanbas

Jql

aJp sulalxe

:Sunqds

yNU,ItW

.{3opue

Lq

paueu

rre ualoJd

aqt;o sued

aql

'utalord

Jqt

ur

pJtuasardar

eq ot

slleJ aua8 aql

ulqll1!\

paluasardar

sr

tPqt

aruanbas

y

:SuDqds

vNu

sP

DaJJe

arues eql spq

Sultqds

ulelord

'aspallnuopua

6uruoq

e

pue

6uoqds uralord

:saqtAtllP

luepua0aput

oMl aAPq sutelUt

]S0[4]

r

'uralur

aql [q

paz[1e1er

sr

6upLlds ura]ot/

o

'pallouuot

elp

sutolxa 6uo1ue1;

aql

leql

felln

e

qons

ur urelord

p

uo4

le^oue]

u/v\o

slr azr\ie1er o1 r\1qrqe

aql seq uroJur u!

o

lrl^lPtPlolnv

sI

6uortdS

uralold

'senprseJ

)

ppe

leq1

suorl

-rear

Surlrpa ur

pellolur

aJe uorlJeJr;o

sad,{1

rlues

eql rJqlJqM

Mou>l

tou

op e14'.{11enper8

srnJJo aruenbas pellpJ

lJaJroJ

Jql

Jo

uorDnJls

-uoJ

JI{t

teql

os

'tou

Jr

paloruJr

pue

'alqeldale

Jr

pJurelJr

'y1qg

aprn8 eql

qlrM

dlrreluaruald

-ruoJ

roJ

p31sJ1

'pJppp

JJe senprsal

n

q)rrlM

ur

sap.{r

anrssa>ns

q8norql

spaarord

uorlJeJr aql

reqt

alqlssod

sl

U

'sdnorS

ur ueql rJqtel

Jturl

e

le

auo

pJppe

JJe sJnprseJ

n

aqt

teql 1se33ns

selnleloru

pallpJ

.dgerued;o

saJntJnrts

aqJ

('3uppa

roy alqrsuodsar

1ou

sr

teql

uolpeJJ

tueJ

-Jaqp

ue aq

ot s:eadde sypg

aprn8 ot sJnprseJ

n

'ypX

aprnb

Jo

uorllalrp

oql.lapun sauAzue

1o

xald

-uor

e fq

pazfleler

ele suoqlpa.l

aql'spue aq11o

uoLlebrl

pue

'n

aqlJo uorlrppp

lo

lp^oruol

'VNU

oqlJo abenealr Aq

slnllo senptsal

n

J0

uotlolap

l0 uotltppv

?*'liJ

S#**:.:

VNH

VNO

ureuS

utolul

uteuS

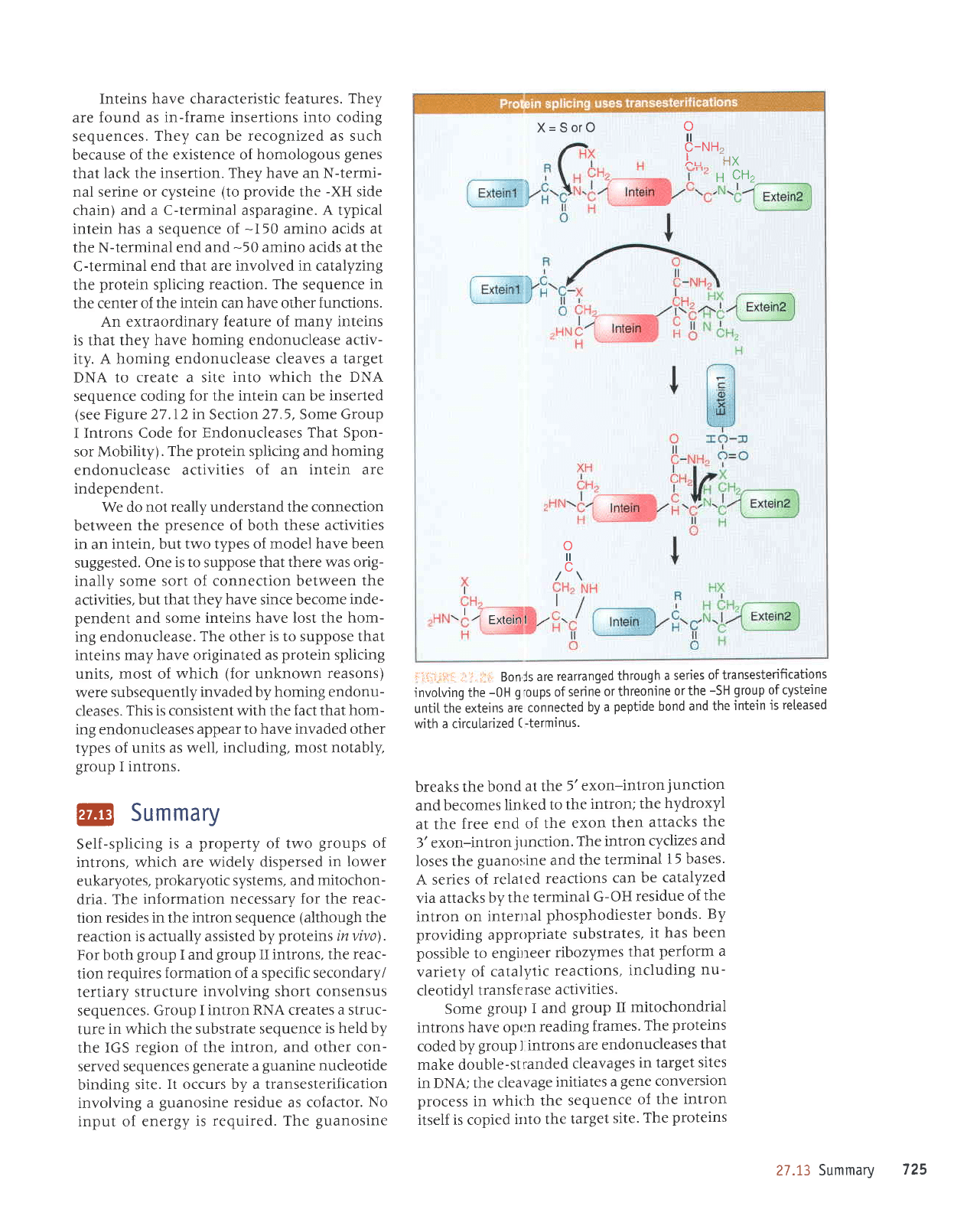

Inteins have characteristic leatures. They

are found as

in-frame insertions into coding

sequences.

They can be recognized as such

because

of the existence of

homologous

genes

that lack the

insertion. They have an N-termi-

nal serine or cysteine

(to provide

the

-XH

side

chain)

and a C-terminal asparagine.

A

typical

intein has a sequence

of

-I50

amino acids at

the N-terminal end and

-50

amino acids at the

C-terminal

end that are involved in catalyzing

the

protein

splicing

reaction. The

sequence

in

the center

of the intein can have other

functions.

An extraordinary

feature

of

many inteins

is that they

have homing endonuclease

activ-

ity. A homing

endonuclease cleaves a target

DNA to

create a site

into

which the

DNA

sequence

coding

for the intein can be inserted

(see

Figure

27.l2in

Section

27.5,

Some

Group

I Introns

Code for Endonucleases

That Spon-

sor Mobility).

The

protein

splicing and

homing

endonuclease

activities of an

intein are

independent.

We do not

really

understand the

connection

between

the

presence

of both these

activities

in an

intein, but two types of model

have been

suggested.

One

is to

suppose

that there was orig-

inally some

sort oI connection between

the

activities,

but that they

have

since become

inde-

pendent

and

some inteins have lost the

hom-

ing

endonuclease.

The

other

is to suppose that

inteins

may have originated as

protein

splicing

units, most of

which

(for

unknown

reasons)

were

subsequently

invaded by homing endonu-

cleases.

This is consistent with the

fact that hom-

ing endonucleases

appear to have invaded other

types of

units as well,

including, most notably,

group I introns.

l@

Summary

Self-splicing

is a

property

of two

groups

of

introns,

which are widely

dispersed in

lower

eukaryotes,

prokaryotic

systems, and

mitochon-

dria.

The

information necessary

for

the

reac-

tion

resides in the intron sequence

(although

the

reaction

is actually assisted by

proteins

in vivo)

.

For both

group

I and

group

II introns,

the reac-

tion

requires

formation of a specific secondary/

tertiary

structure

involving shott consensus

sequences.

Group

I intron RNA creates

a struc-

ture

in

which

the substrate

sequence

is held by

the

IGS region

of the intron, and

other con-

served sequences

generate

a

guanine

nucleotide

binding

site.

It occurs by a transesterification

involving

a

guanosine

residue as cofactor.

No

input of energy

is

required. The

guanosine

i:i{rilli:i

i:lr.r

l

Bonls

are

rearranged

through

a series

oftransesterifications

invotving the

-0H

g'oups

of

serine

or threonine

or

the

-SH

group

of cysteine

untjL

the exteins

ar€ connected

by

a

peptide

bond

and the

intein

is

reteased

with a circularized

(-terminus.

breaks the

bond

at the

5'exon-intron

junction

and

becomes

linked

to

the

intron;

the

hydroxyl

at the

free end

of the

exon

then

attacks

the

3'exon-intron

jtrnction.

The

intron

cyclizes

and

loses the

guanot;ine and

the

terminal

l5

bases'

A series

of relaled

reactions

can be

catalyzed

via

attacks

by the

terminal

G-OH

residue

of

the

intron

on intental

phosphodiester

bonds.

By

providing

appropriate

substrates,

it has

been

possible

to

engitreer

ribozymes

that

perform a

variety

of

catalytic

reactions,

including

nu-

cleotidyl

transferase

activities.

Some

group I and

group II

mitochondrial

introns

have opt:n

reading

frames.

The

proteins

coded by

group

J introns

ate endonucleases

that

make double-stranded

cleavages

in

target

sites

in DNA;

the cleavage

initiates

a

gene

converslon

process in whi<:h

the

sequence

of

the

intron

itself is copied

ilrto the

target

site.

The

proteins

X=SorO

o

tl

c-NH2

j.-

trx

H

CHz

I

\

/'

Exteinl

/

tl

27.13 Summarv

725

coded by

group

II introns

include

an endonu-

clease

activity

that initiates

the

transposition

process,

and

a

reverse

transcriptase

that

enables

an RNA

copy

of the intron

to

be copied into

the

target

site.

These

types of introns probably

orig-

inated

by insertion

events. The

proteins

coded

by both

groups

of

introns

may

include

maturase

activities

that assist

splicing

of the intron

by

sta-

bilizing

the formation

of the

secondary/tertiary

structure

of the active

site.

Catalytic

reactions

are

undertaken

by

fhe

RNA

component

of the RNAase

P ribonu-

cleoprotein.

Virusoid

RNAs

can undertake

self-cleavage

at a

"hammerhead"

structure.

Hammerhead

structures

can form

between

a

substrate

RNA

and a ribozyme

RNA, which

allows

cleavage

to be directed

at

highly

specific

sequences.

These

reactions

support

the view

that

RNA

can form

specific

active

sites that have

catalytic

activity.

RNA

editing

changes

the

sequence

of an

RNA

after

or during

its

transcription.

The

changes

are required

to create

a meaningful

coding

sequence.

Substitutions

of individual

bases

occur in

mammalian

systems;

they take

the form

of

deaminations

in

which

C is con-

verted

to

U or A is

converted

to L

A catalytic

subunit

related

to

cytidine

or adenosine

deam-

inase

functions

as

part

of

a larger

complex

that

has

specificity

for

a

particular

target

sequence.

Additions

and

deletions

(most

often

of uri-

dine)

occur

in trypanosome

mitochondria

and

in

paramyxoviruses.

Extensive

editing reactions

occur in

trypanosome

s in which

as many

as half

of the

bases in

an mRNA

are

derived

from

edit-

ing. The

editing

reaction

uses a

template

con-

sisting

of

a

guide

RNA

that

is complementary

to

the nRNA

sequence.

The reaction

is

catalyzed

by an

enzyme

complex

that includes

an endonu-

clease,

terminal

uridyltransferase,

and RNA li-

gase,

using free

nucleotides

as

the source

for

additions,

or releasing

cleaved

nucleotides

fol-

Iowing

deletion.

Protein

splicing

is an

autocatalytic

reaction

that

occurs

by bond

transfer

reactions

and input

of energy

is

not required.

The

intein

catalyzes

its

own

splicing

out

of the flanking

exteins.

Many

inteins

have

a homing

endonuclease

activity

that is

independent

of the

protein

splic-

ing

activity.

References

Group I Introns

Undertake

Setf-Spticing

by Transesterification

Reviews

Cech, T. R.

(1985).

Self-splicing

RNA: implicarions

for

evolution.

Int. Rev.

Cytol 91,

3-22.

Cech, T. R.

(

1987)

. The chemistry

of

self

-splicing

RNA

and RNA

enzymes.

Science

236,

t532-t5j9.

Resea rch

Been, M. D.

and Cech, T.

R.

(1986).

One

binding

site

determines

sequence

specificity

of

Te

tr ahymena

pre

-rRNA

self

-

splicing,

/rans-

splicing, and RNA

enzyme

activity.

Cell 47,

207-216.

Belfort,

M., Pedersen-Lane,

J., West,

D., Ehren-

man, K.,

Maley,

G., Chu, F.,

and Maley,

F.

(1985).

Processing

of the intron-containing

thymidylate

synthase (td) gene

of

phage

T4 is

at

the RNA level.

Cell 41,

)75-J82.

Cech, T.

R. et al.

(

I 981

).

In vitro

splicing

of

the

rRNA precursor

of Tetrahymena'.

involvement

of

a

guanosine

nucleotide

in

the

excision

of

the intervening

sequence.

Cell 27,

487-496.

I(ruger,

I(.,

Grabowski, P.

J.,

Zatg,

A.

J., Sands,

J.,

Gottschling,

D. E., and

Cech, T.

R.

(1982).

Self-splicing

RNA: autoexcision

and

autocy-

clization

of the ribosomal

RNA

intervening

sequence

of Tetrahymena

Cell 11,

147-1i7.

Myers,

C. A., I(uhla,

B., Cusack,

S., and

Lam-

bowitz,

A. M.

(2002).

tRNA-like

recognirion

of

group

I introns

by a tyrosyl-tRNA

syn-

thetase.

Proc

Natl. Acad.

Sci.

\JSA

99.

2630-26)5.

Group I Introns

Form

a Characteristic

Secondary

Structure

Resea rc

h

Burke,

J. M. et

al.

(1986).

Role

of

conserved

sequence

elements 9L

and 2 in

self-splicing

of

the Tetrahymena

ribosomal

RNA

precursor.

Cell 45,167-176.

Michel,

F. and

Wetshof, E.

(

I 990).

Modeting

of

the

three-dimensional

architecture

of

group

I

catalytic

introns

based on

comparative

sequence

analysis.

J. Mol

Biol. 216,

iB5-610.

Ribozymes

Have

Various

Catatytic

Activities

Cech, T.

R.

(1990).

Self-splicing

of

group

I introns.

Annu

Rev. Biochem

59,54)-568.

Review

726

CHAPTER

27

Catal.ytic

RNA

Re sea

rc h

Winkler, W. C., Nahvi,

A., Roth, A.,

Collins, J.

A.

and Breaker, R. R.

(2004).

Control of

gene

expre ssion by a natural metabolite-responsive

ribozyme. Nature 428, 281-286.

@

Some Group I Introns Code for

Endonucleases That Sponsor Mobil.ity

Review

Belfort, M. and Roberts, R. J.

(1997).

Homing

endonucleases: keeping the house in order.

Nucleic Acids Res. 25. J)79-)388.

Group

II Introns May Code

for Multifunction

Proteins

Reviews

Lambowitz, A. M. and Belfort, M.(1993).

Introns

as

mobile

genetic

elements. Annu- Rev.

Biochem. 62, 587-622.

Lambowitz, A.

M.

and

Zimmerly,

S.

(2004).

Mobile

group

II introns. Annu. Rev.

Genet

38,

l-35.

Resea

rc h

Dickson,

L., Huang, H. R., Liu, L., Matsuura,

M.,

Lambowitz,

A. M.,

and

Perlman, P. S.

(2001).

Retrotransposition of a

yeast group

II intron

occurs

by reverse splicing directly into ectopic

DNA

sites.

Proc Natl. Acad. Sci USA 98,

r)207-rj2r2.

Zimmerly, S. et

al.

(1995).

Group

II intron mobil-

ity occurs by target DNA-primed

reverse tran-

scription. Cell

82, 545-554.

Zimmerly, S. et

al.

(1995).

A

group

II intron

is

a

catalytic

component of a DNA endonuclease

involved

in intron mobility. Cell 8j,

529-5)8.

Some

Autosplicing Introns Require

Maturases

Resea rch

Bolduc et al.

(2003).

Structural

and biochemical

analyses of

DNA

and

RNA binding by a

bifunctional

homing endonuclease and

group

I

splicing

factor. Genes. Dev. 17, 2875-2888.

Carignani, G. et

al.

(1983).

An RNA maturase

is

encoded by the

first intron of the mitochon-

drial

gene

for

the subunit

I of cytochrome oxi-

dase in S. cerevisiae. Cell

]5, 7j3-7 42.

Henke, R. M., Butow,

R. A.,

and

Perlman, P. S.

(

1995

).

Maturase and endonuclease

func-

tions

depend on separate conserved

domains

of the bifunctional

protein

encoded by the

group

I intron aI4 alpha of

yeast

mitochon-

drial

DNA. EMBO J. 14, 5094-5099.

Matsuura, M., No;rh,

J. W.,

and Lambowitz,

A. M.

(200 l). Meclranism

o[

malurase-promoted

group

II intron splicing.

EMBO J

20,

7259-7270.

Viroids

Have Catatytic

ActivitY

Reviews

Doherty, E.

A.

ani

Doudna,

J.

A.

(2000).

Ribozyme strlrctures

and

mechanisms.

Annu Rev.

Biochem.

69,597-615.

Symons,

R. H.

(

I 992

).

Small

catalytic

RNAs.

Annu Rev.

Biochem. 61,641-671.

Resea rc h

Forster, A. C. and

Symons,

R.

H.

(1987). Self-

cleavage

of

virusoid

RNA is

performed

by

the

proposed

55-nucleotide

active site.

Cell 50,

9-t6.

Guerrier-Takada,

tl.,

Gardiner,

K., Marsh,

T., Pace,

N., andAltman,

S.

(1983).

The RNAmoiety

of

ribonuclear;e

P is the

catalytic

subunit

of the

enzyme.

Cell )5,

849-857.

Scott, W. G.,

FinclL,

J. T.,

and

ICug, A.

(I995).

The

crystal

structrtre

of an

all-RNA

hammerhead

ribozyme:

a

proposed mechanism

for

RNA

catalytic

cleavage.

Cell

81, 991-1002.

RNA

Editing

Occurs

at

IndividuaI

Bases

Resea

rc h

Higuchi, M. et al.

(19931.

RNA

editing

of AMPA

receptor subunit

GluR-B:

a

base-paired

intron-exon

structure

determines

position

and

efficiency. CeU

75, l)61-l)70.

Navaratnam,

N e:.

al.

(

I 995

).

Evolutionary

origins

of apoB

mRNA editing:

catalysis

by a cytidine

deaminase

that

has acquired

a

novel

RNA-

binding

motit at

its active

site. Cell

81,

r87-195.

Powell. L.

M.. Wattis,

S. C.,

Pease,

R. J.,

Edwards,

Y. H., Knott,

'f.

J., and

Scott,

J.

(1987). A

novel form ol

tissue-specific

RNA

processing

produces

apolipoprotein-B48

in

intestine.

Cell

50,83I-840.

Sommer,

B. etal.

(1991).

RNAeditinginbrain

controls

a delerminant

of ion

flow

in

gluta-

mate-gated

c.eannels.

Cell

67

,

ll-19.

RNA Editing

Can

Be

Directed

bv

Guide

RNAs

Aphasizhev

R.,

Slticego,

S.,

Peris,

M., Jang,

S.

H.,

Aphasizheva,

I., Simpson,

A.

M., Rivlin,

A',

and Simpson ,

L.

l2OO2).

Ttlpanosome

mito-

chondrial

3'

lerminal

uridylyl

transferase

(TUTase):the

key enzyme

in U-insertion/

deletion

RN,a.

editine.

Cell

108,

637-648.

Researc

h

References

727

Benne,

R., Van

den Burg J., Brakenhoff,

J. P.,

Sloof, P., Van Boom,

J. H.,

and Tfomp, M.

C.

(I986).

Major

transcript

of the frameshifted

coxll

gene

from

trypanosome

mitochondria

contains four

nucleotides

that are not

encoded

in

the DNA.

CeU 46,819-826.

Blum,

B., Bakalara,

N., and

Simpson, L.

(1990).

A

model for RNA

editing in kinetoplastid

mito-

chondria:

"guide"

RNA

molecules

transcribed

from

maxicircle

DNA

provide

the edited infor-

mation.

Cell 60, 189-198.

Feagin,

J. E., Abraham,

J. M.,

and Stuart, K.

(1988).

Extensive

editing

of the cytochrome

c

oxidase III

transcript in Trypanosoma

brucei.

Cell

51,4I)422.

Seiwert,

S. D., Heidmann,

S.

and

Sruarr, K.

(1996).

Direct

visualization

of

uridylate deletion

in

vilro

suggests

a mechanism for

kinetoplastid

editing.

Cell

84,831-841.

Protein

Spticing Is Autocatalytic

Review

Paulus,

H.

(2000).

Protein

splicing

and related

forms of

protein

autoprocessing.

Annu Rev.

Biochem. 69,447496.

Research

Derbyshire, V.,

Wood, D.

W., Wu, W.,

Dansereau,

J. T., Dalgaard,

J.2., andBelfort,

M.

(1997).

Genetic definition

of a

protein-splicing

domain: functional

mini-inteins

support

structure

predictions

and

a model for

intein

evolution.

Proc. Natl. Acad.

Sci.

USA 94.

tt466-tt47t.

Perler,

F. B.

et al.

(L992).

Intervening

sequences in

an Archaea

DNA

polymerase

gene.

Proc. Natl.

Acad

Sct. USA 89, 5577-5581.

Xu, M.

Q.,

Southworth, M.

W., Mersha,

F. B.,

Hornstra,

L. J., and Perler,

F. B.

(19931

. in

vitro

prorcin

splicing

of

purified

precursor

and

the identification

of a branched

intermediate.

Cell

75,

liTl-1377.

728

CHAPTER

27

Catatytic

RNA

6ZL

aODd

lrau

uo

panuquoJ

'solnqnlorrrru

0l uorllauuol aql

apr^old

Aeu saxaqduor

oMl asaql

lrouuol 1eq1

suralold eq1

r

'uorllunJ

luoruorluor r0J

lprtuassa

s!

III-lCl

ol spurq

1eq1

xaldLuor

urelord

gg93

aq1

r

'II-l0l

]P

pau.loJ

sr alnllnrls urlPurolql

lPnsn

aql

ol anrlpurallp up sr

1eq1

xaldLuor uralord

pazrlerrads

y

o

xalduol uralord

p

spur.€ alauorluel eqf

'11-363

uorbar Llrp-I-V aql

)uplJ

tpq]

III-I0l

pue

I-l0l

soluonbos

pa^rasuol

iloqs

oql

lo

lslsuol

sluauala

Nll

o

'srsolrru

1e

[1e1elnrre ale6erEas o1

pruseld

e rvrolle

o1

fi1L1Lqe eq1

f,q

aostaatals u!

pagquepr

a.lp sluouala

[!]l

r

anLst^dil

's

ur saluanbas

vNo

iloqs

a^eH salauollual

'uMoul

lou

sr

yp6

enrlLladar oql

Jo

uor]lunJ aLlf

o

'yp6

enqLladar

lo

slunoue abrel

uleluol

seuosouro.lql rrlofile4na raq6rq uL se]euor]uol

o

vN0

a^qqaoau ureluol APhl salau.lorlual

'salu0n00s

vN0

alrtleles

ur

qlu

sr.

leql

urleur0rql0ralaq a^Pq uolJo s0.r0ruo.llu0l

o

'uorDal

lueuorlual slr ur suuoJ

lPql

eroqrolauq aql ol salnqnlo.llrur

Jo

luauqrPlle

oql

r\q

elpuLds

lrlolru aql uo

plaq

sr auosorxo.lql rrlofire1na

y

o

alnao uoqe6ar6as e sI aurosoruolql lqo^rPln3 aql

,,'sgnd,.

e,rLb o1

puedxe

sauos

-ourolql

euefiod uo

uoLssardxa auab

1o

salrs ale

]p{}

spuefl

r

uorssaldxl

auag

Jo

salrs

le

puedxl

sauosourolLll

eual^lod

'deu

1err6o1o1Ar

e se

pasn

oq upl

1eq1

spupq

lo

soues e eneq suereldLp

Jo

sauosoruo.lql ouolnlod

.

spuPg rulol saurosoruorql aual,{lod

'srxp

leu0s0ul0rql

aql ulorJ

popualxa

ale

leql

s00ol

MOqS seuosouroiqr

qsnlqduel

uo uoLsserdxa auab

Jo

solr$

r

papuaul

arv sauosouorql

LlsnlqouPl

'spueqlolut

qlP-l-9

aql ut

polellualuol

alP sOUO!

r

'spuPqlalut

aql ueql

}uolu0l

l-!

ut iaMol elP spuPq oql

r

'spueq-9

pallpr

ale

qlrqM

'suorlpuls

Jo

sauas

p

Jo

oluereadde aql

a^pq ol sauosoruo.lql

aq] asnPl sanbruqlal 6ururels ur.P|.lol

I

sulailed 6uLpueg a^eH sauosorxorql

'asPq0lelut

ln0

-qbnorql

palred Alasuap utPual

ugeuolqlolaloq;o

suor6eX

.

's0ruosou0rql

llloltul

upql

pelred A11q6q ssel

st

qrtqM

'utlsuolqlna

Jo

ulloJ

aql

ur sr. urleuorlll

Jo

sseu

lelauab

aql

'asPqdlalut

6uun6

r

'srsolrur

6uunp

r{1uo uaes

oq uPl

seuosouto.l!r

lPnpLnLpul

r

u tlPtuoJ

LllolalaH

pue

utlPtx0lqlnl

olut

papl^]o sI ullPtu0lql

'0luenDos

sns

-uesuol

llJDads

fiue aneq

lou

op

]nq

ql!-.l-V

ore

sl!fi otlf

r

'suvs

ro suvt/\l

pollPl

sesuanbes

llJt]eds

lP

xllleu .lPallnu

eql 01

poqrPne

s!

vNo

r

xulew aseqdralul

ue

o1

vNo

qlPnv

saluanbas

llJllads

'peqrellP

aie

vN0

paltoriadns

1o

sdool eq1

qrtq/v\

01

ploljels utalold P

aAeq sauosotllo.ltll

ose{oP}e}rl

o

'qI

98-

Jo

sutPulop

luepuadoput

olur

palrolradns [1art1e6au st

utlPtuo.lq]

asPqdra]ut

J0

vN0

.

plo#Prs

e

o]

paqlP]lv suteuo0

puP

sdool sPH

vN0

lqo,{rP)nl

'dq

gg1/rorredns

I-

sr. butttor.redns

;o

flrsuap

a6erane

aq1

r

'sureu0p

polrolladns [1anL1e6au

]uapuedaput

ool-

sPq

ptoellnu

0q1

.

paltolredns

{

auiouo!

leuape8

aqt

'polJquapt

uaoq

lou

e^eq

VN6

eql 6uLsuepuor

loJ alqtsuodsal

ale

lPql

suralotd

aql

r

'uralold

lo

VNU

uo

llP leql

sluabe

^q

paploJun

oq uel

pue

ssPu

nq

vNo

%08-

st

ptoallnu

lPua]leQ

aLll

o

ptoallnN

e sI auoua9

lPuellP8

otll

'llaqs

ut010lo

polquasseald P olut

vNo

oql

uesul

sasnlt^

vNo

lsluoqds

.

'1r

punole

llaqspeeq

aql alquassP

Aeql se

euouab

VNU

aqt

asuapuol

sasur^

VNU

sno]ueulelll

r

'pasuapuol

filaualya

st

lleqspPaq

aql uttlltM

plle

ltelrnI

o

'lloqspPaq

eq]

Jo

alnllnlls

oql

fq

paltultl

sr snlh

P olut

polPlod.lolu!

eq uPl

lPql

vNo;o

q16ua1 eql

r

sleol

ltaql olut

pabellPd arv

sauoua!

lPlL^

u0qlnpollul

3Nrtrn0

u3l-dvH3

rflfir

wm

Telomeres

Have

Simpte Repeating

Sequences

o

The

te[omere is required

for

the stabitity

of the

chromosome end.

r

A

tetomere consists

of a simpte repeat

where

a C + A-rich

strand

has

the seouence

cr(A/r)F4.

Te[omeres

Sea[ the

Chromosome Ends

.

The

protein

TRF2

catalyzes

a

reactjon

in

which

the 3'

repeating

unit of the G

+

T-

rich

strand

forms

a

loop by disptacing its

homotog

in an

upstream region

of the

telomere.

Telomeres Are

Synthesized

by a

Ribonucteoprotein Enzyme

o

Tetomerase

uses the 3'-0H

of the G + T

telomeric strand to

prime

synthesis of tan-

dem

TTGGGG reoeats.

.

The RNA component

of telomerase has

a

sequence that

pairs

with the

C

+

A-rich

repeats.

r

One of the

protein

subunits

is

a reverse

transcriptase

that uses the RNA

as temptate

to synthesize

the G

+ T-rich

sequence.

Te[omeres Are

EssentiaI for

SurvivaI

Summarv

@

Introduction

A

general

principle

is

evident in

the organiza-

tion of all

cellular

genetic

material. It

exists as

a compact

mass that is

confined

to a limited vol-

ume,

and its various

activities,

such as replica-

tion and

transcription,

must

be accomplished

within

this space. The

organization

of this mate-

rial

must accommodate

transitions

between

inactive

and

active states.

The

condensed

state of nucleic

acid results

from its

binding

to basic

proteins.

The

positive

charges

of these

proteins

neutralize

the nega-

tive

charges

of the nucleic

acid. The

structure

of

the nucleoprotein

complex

is determined

by

the interactions

of the

proteins

with the DNA

(or

RNA).

A common problem

is

presented

by the

packaging

of DNA

into

phages,

viruses,

bacre-

rial

cells, and

eukaryotic

nuclei. The

length

of

the DNA

as an extended

molecule

would vastly

exceed the

dimensions

of the

compartment

that

contains

it. the DNA

(or

in

the case

of some

viruses,

the RNA) must

be compressed

exceed-

ingly

tightly to fit into

the

space avallable.

Thus

in contrastwith

the customary

picture

of DNA

as an

extended doubk helix,

structural deformation

of DNA

to bend or

fold

it into

a mlre clmpact

form

is the rule

rather than

exceotion.

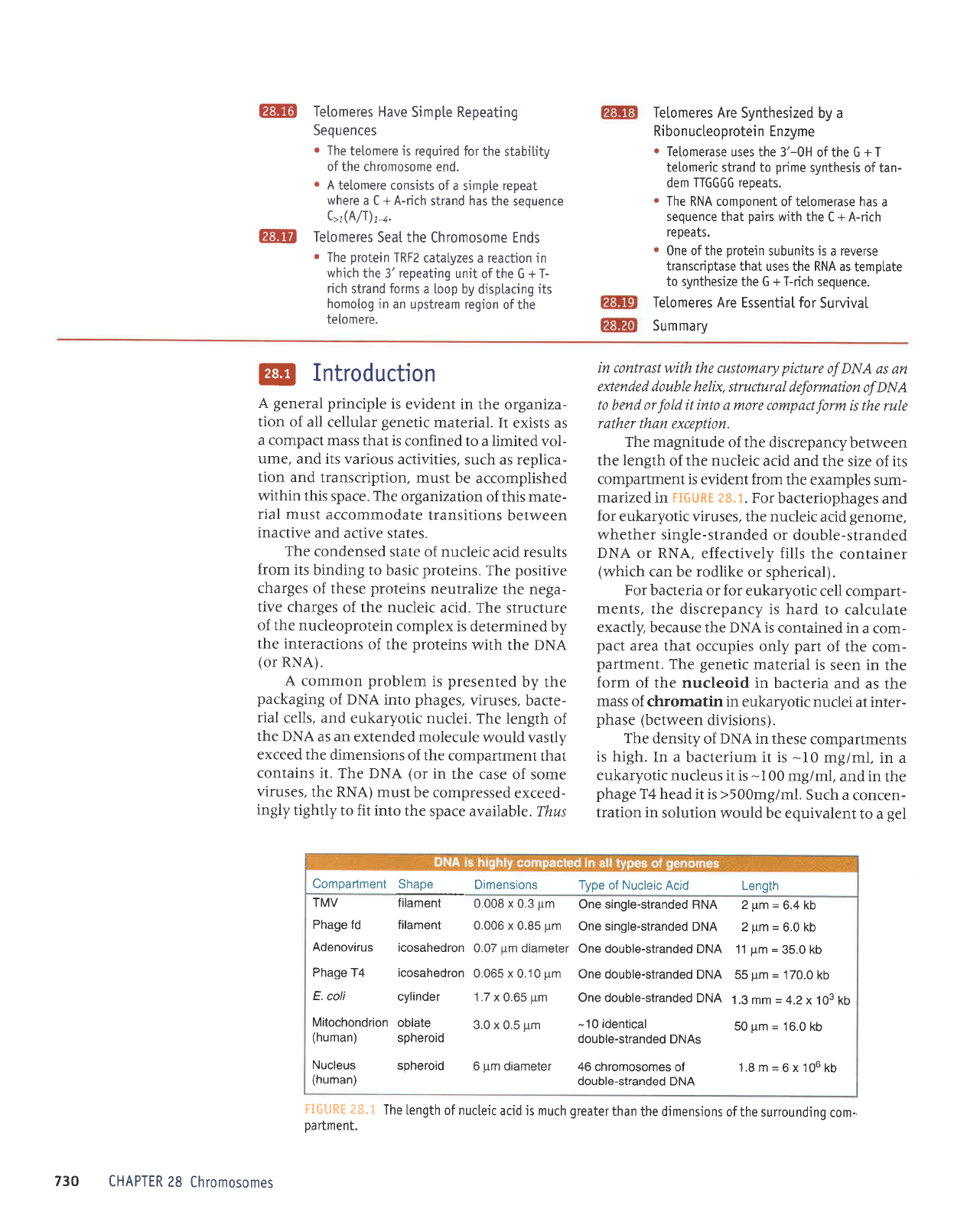

The magnitude

of the

discrepancy

between

the

length

of the nucleic

acid and

the size

of

its

compartment

is evident ftom

the examples

sum-

marized

in

FIGUHt

eS.1.

For bacteriophages

and

for eukaryotic viruses,

the nucleic

acid

genome,

whether

single-stranded or

double-stranded

DNA

or

RNA,

effectively fills

the

container

(which

can be rodlike

or spherical).

For

bacteria or for

eukaryotic

cell compart-

ments, the

discrepancy is hard

to calculate

exactly,

because the DNA is

contained in

a com-

pact

area

that occupies

only

part

of the com-

partment.

The

genetic

material

is

seen in

the

form

of the nucleoid

in bacteria

and

as the

mass

of chromatin in eukaryotic

nuclei

at inter-

phase (between

divisions).

The density

of DNA in these

compartments

is

high. In a

bacterium it is

-10

mg/ml,

in

a

eukaryotic

nucleus it is

-100

mg/ml,

and in

the

phage

T4 head

it is

>5O0mg/ml.

Such

a concen-

tration

in solution

would be equivalent

to a

gel

ftfi'-lHHf;S.t

TheLengthofnucleicacidismuchgreaterthanthedjmensionsofthesurroundingcom-

Dartment.

Compartment

TMV

Phage fd

Adenovirus

Phage T4

E.

coli

Mitochondrion

(human)

Nucleus

(human)

Shape

filament

filament

icosahedron

icosahedron

cylinder

oblate

spheroid

spheroid

0.008 x

0.3

pm

0.006 x 0.85

pLm

0.07

pm

diameter

0.065 x

0.10

pm

1.7 x

0.65

pm

3.0 x

0.5

pm

6

pm

diameter

Dimensions Type

of Nucleic

Acid

Length

One single-stranded RNA

One single-stranded

DNA

One

double-stranded DNA

One

double-stranded DNA

One double-stranded

DNA

-10

identical

double-stranded

DNAs

46 chromosomes

of

double-stranded

DNA

2pm=6.4kb

2pm=6.0kb

11

pm

=

35.0 kb

55

pm

=

170.0

kb

1.3mm=4.2x103kb

50

pm

=

16.9 16

1.8 m

=

6 x 1Oo kb

730

CHAPTER

28

Chromosomes