Lerbinger O. Corporate Public Affairs. Interacting with Interest Groups, Media, and Government

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ideals of social justice, human rights, and environmental preservation—

ideals that resonate with the general public. Furthermore, some groups

are headed by strong popular leaders, such as Ralph Nader and Jesse

Jackson, and their causes are often endorsed by celebrities, as with

Meryl Streep’s support of the Alar campaign.

19

In contrast, business is

weakened by a lack of the kinds of core values that can win the minds

and hearts of Americans. Business is typically perceived as concentrat

-

ing too heavily on the bottom line and on increasing shareholder value

at the expense of the public interest.

Occasionally, the strong motivations that exist on the local level also

appear on the national level when specific issues, such as the environ

-

ment, are at stake. However, on a national level, public interest groups

are usually so diversified in their interests and causes they fail to present

a common political front. They also compete with one another in ob

-

taining government and private funding.

Internet Power. Added to the arsenal of activist groups is the power

of the Internet. It boosts the effectiveness of activist groups because it

enables them to mobilize their members and sympathizers much more

efficiently than they could in the days before websites and e-mail. “For

very, very little cost, you can have amazing effect, if you have real

grassroots power out there,” says Margaret Conway, managing direc-

tor of the Human Rights Campaign, the largest U.S. political organiza-

tion for gays and lesbians.

20

Andrew Kohut, director of the Pew Research

Center for the People & the Press, notes, “People are now bonded together

in communities that were very loosely knit or did not exist at all 10

years ago.”

21

Activists are supported by numerous websites. On Protest Net, Evan

Henshaw-Plath posts information about hundreds of protests, meet-

ings, and conferences, most of which are left-leaning in their politics.

Another site, E-The People, gives viewers hundreds of petitions to choose

from and 170,000 e-mail addresses of government officials. To learn

how to contact officials at the national, state, and local levels, people can

consult the Electronic Activist site.

22

BusinessWeek concludes that “in the Internet Age, it’s possible for a

handful of Web-savvy activists to exert pressure on policymakers work

-

ing out of their homes. The result may be a fundamental transforma

-

tion of the nature of politics.”

23

The Internet enables activist groups to

recruit members and volunteers, raise money, inform their members

about the organization’s position on issues, organize protests and ral

-

lies, and lobby lawmakers. Greenpeace is credited with having an e-mail

list of 5,000 activists “who join protests over everything from polyvinyl

chloride in Japanese toys to plutonium shipments in Britain.”

24

Corpo

-

rate public affairs professionals recognize that the Internet has in

-

creased the power of activist groups, making money a less important

factor in the political marketplace.

32 I PART II

Credibility Power. NGOs, such as Greenpeace and Amnesty Interna

-

tional, are generally more trusted and respected than governments, me

-

dia, and corporations. This contention was supported by a survey of 500

respondents aged 34 to 64 in several countries (United States, France,

Germany, Australia, and the United Kingdom) conducted by the Strategy

One unit of Edelman PR Worldwide. Steve Lombardo, president of Strat

-

egy One, said, “These [respondents] are two to three times more likely to

trust an NGO to do what is right compared to a large company because

they are seen as being motivated by morals rather than just profit.” Over

-

all, 64% said the influence of NGOs has increased significantly over the

decade, with 80% saying Greenpeace is highly effective and 78% saying

the same of Amnesty International. Only 11% saw governments or cor

-

porations making the world a better place. In the United Kingdom, 65% of

respondents rated the World Wildlife Fund favorably, as did 50% for

Greenpeace, 29% for British Airways, and 13% for Exxon-Esso.

25

Tactics Used by Social Action Groups

Over a quarter of Americans belong to “cause organizations,” according

to the Times Mirror Center for People and the Press.

26

The actions taken

by these members vary widely. Some engage in traditional lobbying ef-

forts, whereas others take direct action through the use of protests,

boycotts, and shareholder resolutions. A 1994 Gallup poll reveals some

relatively conservative political actions by Americans: 25% have “worn

a campaign button or displayed a campaign poster,” 25% have “asked

someone to vote for your candidate,” 22% have “gone to a political

meeting to hear a candidate speak,” and 14% have “worked for a politi-

cal party or candidate.”

27

An international study classified political activist groups into five

types: inactive, conformists, reformists, activists, and protesters. The

repertory of direct actions taken by them increases with each type. In

-

actives might do no more than glance at political news and sign a peti

-

tion if asked; reformists might engage in “moderate” levels of protest,

such as lawful demonstrations and boycotts; and protesters would

shun any conventional involvement in favor of aggressive protest

methods, including violence.

28

Philip Lesly, a public relations consultant, devised an equally useful

range of categories for opposition groups along with strategies to deal

with each:

• Advocates: Propose something they believe in; for example, busi

-

ness proposes lower taxes to help the economy. Use the strategy of

reason.

• Dissidents: Against something, or many things, because it’s their

character to be sour on things as they are. They use logic and se

-

lected emotions.

INTEREST GROUP STRATEGIES I 33

• Activists: Want to get something done or changed: “Don’t just

stand in the picket line—do something.” May push legislation,

stop construction of highway, or urge an amendment forbidding

abortion. They use logic and strategic actions.

• Zealots: Distinguished by overriding single-mindedness, absorbed

with one issue such as stopping a power plant or liberating a geo

-

graphic area of social groups. Egocentric, must run the show, con

-

sider moderates to be enemies. They use the strategy of creating

climate of opinion and understanding among the public, which

isolates zealots and may wither their zeal.

29

An extreme example of zealots are members of the Earth Liberation

Front (ELF), a furtive ecoterrorist group. To stop forest development, they

have claimed responsibility for burning two Vail, Colorado, lodges and

torching homes under construction in California. More recently they set

fire to three auto dealerships in the Los Angeles suburb of Duarte, char-

ring or damaging more than 40 SUVs, mostly gas-guzzling Hummer

H2s. The ELF website contains how-to manuals for setting fires and tips

on evading police. Attackers have evaded police because “It’s such a shad-

owy, loose-knit collection of cells that it’s hard to find them.”

30

Many business crises have been triggered by social action groups be-

cause one of their favorite strategies is to target large, visible corpora-

tions whose concern for their reputations makes them vulnerable. By

threatening to seek government intervention or further regulation, the

numerous social action groups have succeeded in pressuring corpora-

tions to accede to their demands. By classifying a specific group accord-

ing to this typology, a corporation can better decide how to deal with it

(e.g., whether to agree to a meeting).

ENDNOTES

1. Jeffrey M. Berry, The Interest Group Society, 3rd Edition (New York: Longman,

1997), p. xi.

2. Ibid., p. 4.

3. Ibid., pp. 6–8.

4. See table of contents in Foundation for Public Affairs, Public Interest Profiles,

1992–1993 (Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, 1992).

5. See Robert L. Rose, “New AFL-CIO President Seeks to Revitalize Old Federa

-

tion,” Wall Street Journal, October 29, 1996, p. B1.

6. These are discussed in Jarol B. Manheim, The Death of a Thousand Cuts: Corpo

-

rate Campaigns and the Attack on the Corporation (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates, 2001).

7. “Social Policy Themes,” Social Policy, Vol. 32, Winter 2001/2002, p. 2.

8. “After Seattle—Citizens’ Groups: The Non-governmental Order,” Economist,

December 11, 1999, p. 21.

9. Nature’s Voice, September/October 2004, p. 1.

10. Theodore Levitt, The Third Sector: New Tactics for a Responsive Society (New

York: AMACOM, 1973), p. 73.

34 I PART II

11. John M. Holcomb, “Citizen Groups, Public Policy, and Corporate Responses,”

in Practical Public Affairs in an Era of Change: A Communications Guide for

Business, Government, and College, ed. Lloyd B. Dennis. (Lanham, Md.: Uni

-

versity Press of America, 1996), p. 209.

12. Based on comment by Michael McDermott and Jonathan Wootliff in a ses

-

sion on “Building Relationships with Non-Government Organizations,” at

Public Relations Society of America Conference in Atlanta, Georgia, October

2001; also see pr reporter, November 5, 2001.

13. Yvonne Lo, editor, A Public Relations Guide to Nonprofits (Exeter, NH: PR Pub

-

lishing Company, 2003), p. vii.

14. Charlotte Ryan, Prime Time Activism: Media Strategies for Grassroots Organiz

-

ing (Boston, Mass.: South End Press, 1991), p. 29. Another source of infor

-

mation about the media practices of nonprofits and activists is Jason

Salzman, Making the News: A Guide for Nonprofits and Activists (Boulder, CO:

Westview Press, 1998). This handbook is based on interviews with media-

savvy activists and 25 professional journalists.

15. Carl Boggs, The End of Politics: Corporate Power and the Decline of the Public

Sphere (New York: Guilford, 2000), p. 258.

16. Groups with large geographically dispersed memberships, however, can du-

plicate and multiply the power of community groups. Members can

strongly identify with the often single-cause political and social goals of

their chosen organizations, especially in times of conflict with corporations

or government.

17. Doug Nurse, “Professor Fertilizes Grassroots; Sociologist Has studied Com-

munity Activism for a Quarter of a Century,” Atlanta Journal, November

27, 1997, p. 22E.

18. Activist groups devote a lot of their efforts to organizing their members. In

his recent book, Corporations Are Gonna Get Your Mama (Monroe, Maine:

Common Courage Press, 1996), Kevin Danaher, an activist, proclaims, “De-

mystify the system and teach ourselves how to organize alternatives” (p.

199). He cites several training sources that provide help, among which are

the Center for Third World Organizing, ACORN (Association of Community

Organizations for Reform Now), and the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF).

Stating the goal of developing ways to control the behavior of corpora-

tions, Danaher says that “Government and citizens’ movements have been

pushing on many fronts to codify rules on how corporations can treat

their workers, customers, and the environment. Extending his reach inter

-

nationally, he credits the National Labor Committee in New York for suc

-

ceeding in forcing The Gap to improve working conditions in its El

Salvador factories. NLC had generated widespread publicity about dismal

working conditions of girls as young as 13 “who toil in Central American

sweatshops up to seventy hours a week earning less than 60 cents an

hour.” The Gap signed an agreement with (NLC) on December 15, 1995,

that establishes new standards for health and safety and protection of hu

-

man rights, subject to independent monitoring of its contractors. Gayle

Liles, “The U.S.-Salvador Gap,” op. cit., p. 177.

19. See “How a PR Firm Executed the Alar Scare,” Wall Street Journal, October 3,

1989, p. A22.

20. Ibid., p. 9.

21. Ibid., p. 11.

22. Edward Harris, “Web Becomes a Cybertool for Political Activists,” Wall Street

Journal, August 5, 1999, p. B11.

INTEREST GROUP STRATEGIES I 35

23. Pete Engardio, “Activists Without Borders,” BusinessWeek, October 4, 1999,

p. 144.

24. Ibid., p. 150.

25. O’Dwyer’s PR Service Report, February 2001, pp. 1, 26.

26. Holcomb, op. cit., p. 211.

27. “Election Preview,” American Enterprise, Vol. 7, January/February 1996, p.

88.

28. Alan Marsh, “The New Matrix of Political Action,” Futures, Vol. 11, April

1979, p. 98.

29. Philip Lesly, Managing the Human Climate, May–June 1978.

30. Ronald Grover, “Burning to Save the Planet,” BusinessWeek, September 8,

2003, p. 41.

36 I PART II

Chapter 2

Interest Group Strategies

and Forms of Opinion Leader

Communication

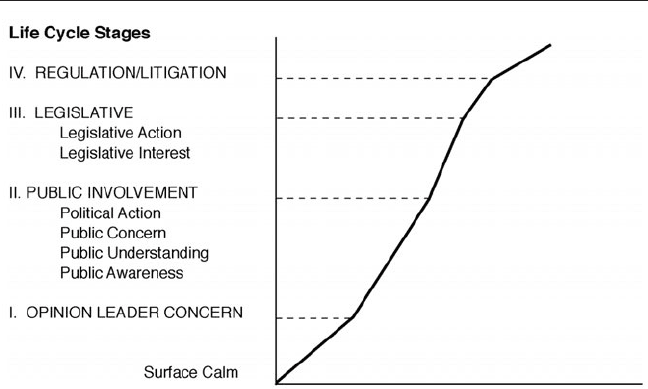

Societal issues are rooted in people’s dissatisfaction with their experi-

ence as consumers, employees, members of cause organizations, or vic-

tims of dislocation or crises. In addition, some people in the activist

third-sector groups have deeper resentments and want to change the

status quo. In both cases, people in these groups form interest groups,

or, alternatively, existing groups may take up their dissatisfactions. So-

cietal issues also arise from the initiative of so-called public interest

groups whose thought leaders and opinion leaders conceive and develop

issues for which they seek public support. In both situations, the life cy-

cle of an issue begins with an emerging issue.

As with all ideas and issues, months and usually years are needed for

them to become widely accepted and adopted. Furthermore, when ideas

concern public policy, they are, because of their controversial nature,

contested by a variety of political participants. Thus, the proponents of

an issue face an uphill struggle to build up enough “social energy”—

enough highly motivated people—to convince the public that their issue

deserves priority.

1

An emerging issue goes through several life cycle

stages, as shown in Fig. 2.1.

Corporations practicing modern public affairs begin the issues man

-

agement process by constantly monitoring their external environ

-

ments for early warning signals of emerging issues initiated by

interest groups that might affect them. They thus begin the issues

management process. After identifying, prioritizing, and analyzing an

issue, a company engages in strategy formulation to decide what ac

-

tions to take or not take.

37

As part of their political strategies, corporations can also be the initi-

ators of issues of concern to them. Regulations that deal with price, en-

try, and trade practices have often been sought by business because

they provide industry with such benefits as stability and protection

against competitors. Much uncertainty, disliked by business, is thus

reduced.

2

Therefore some companies may seek new laws and regula-

tions or a change in existing ones; for example, Enron Corporation lob-

bied hard for deregulation in the energy industry. For many years the

federal regulation of transportation through the Interstate Commerce

Commission (ICC) was actively supported by the regulated industries.

There was no stronger protector of the ICC against threats of deregula

-

tion than the trucking industry.

3

Support or opposition to regulations

is one way a public affairs strategy contributes to a firm’s marketing

strategy. The main thrust of this chapter, however, is to examine the

strategies used by corporations in response to initiatives taken by non

-

business interest groups.

INTEREST GROUPS DEVELOP CAMPAIGNS

TARGETING CORPORATIONS

In recent decades, nonbusiness interest groups have developed sophisti

-

cated strategies and tactics to confront corporations. Borrowing some

ideas from the Far Left (e.g., from Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals

4

) and

several social movements, labor unions developed the strategy of the

corporate campaign. In his The Death of a Thousand Cuts, Jarol B.

38 I CHAPTER 2

FIG. 2.1. Build-up of social energy: four stages in life cycle of an issue.

Manheim of George Washington University defines and describes it as

“an assault on the reputation of a company that has somehow offended

a union or some other interest.”

5

Manheim points out that although or

-

ganized labor became the principal initiator of corporate campaigns

from the mid-1970s, other groups—notably environmentalists, human

and civil rights advocates, and feminists—have also employed the strat

-

egy. Some of these other groups often have a much stronger anticorpo

-

rate ideological basis than the typical labor campaign by relying for

their motivation and approach on philosophical opposition to the cor

-

poration per se. Manheim calls their efforts “anticorporate campaigns.”

In contrast, unions have a more obvious self-interest-based economic

motivation and should not be viewed as anticorporate.

6

Union Faces Off With Farah and J. P. Stevens

The union corporate campaign strategy was launched when the Amal-

gamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA) sought to unionize

workers in Farah Manufacturing Company’s new plant in El Paso in

1972. Seeing that the usual tactic of a strike was ineffective—largely be-

cause so many Mexican replacement workers were available—the

ACWA launched a nationwide boycott, which was the first time a labor

organization had used that tactic to organize a workforce. Mass picket-

ing became a natural for TV news coverage. On December 11, 1972,

called “Don’t Buy Farah Day,” 175,000 pickets marched nationwide.

7

An important feature of a corporate campaign is the link between la-

bor and other interest groups. Because most of ACWA’s members were

Catholics, support was easily obtained not only from the pastor of El

Paso’s largest parish, but from the Most Reverend Sidney M. Metzger,

bishop of El Paso. A letter addressed by him “to all Catholic Bishops in

the United States,” which recommended the boycott of Farah slacks,

was part of a full-page ad placed by ACWA in newspapers in the 13 larg

-

est advertising markets to call attention to what it called unfair labor

practices at Farah. Cardinal Mederios of Boston reflected the views of

many religious leaders when he said, “the internal affairs of business be-

come the concern of religious leadership when violations of social justice

and human dignity are at stake.”

8

Farah capitulated on February 24,

1974, by ratifying an agreement with the union. The use of prominent

leaders and placement of ads in support of the national boycott were

instrumental in the union’s success.

Union corporate campaign tactics were soon extended in the union’s

conflict with J. P. Stevens, a diversified corporation, primarily concen

-

trated in the textile industry with the majority of its plants located in

North and South Carolina. The main issue was the company’s refusal to

bargain collectively with plants where workers had accepted a union—

even after condemnation by the National Labor Relations Board and a

federal appeals court, which stated that “never has there been such an

INTEREST GROUP STRATEGIES I 39

example of such classic, albeit crude, unlawful labor practices.”

9

Besides

declaring a national boycott on a scale greater than that ever under

-

taken by the American labor movement, the union began the campaign

in earnest in 1976 by employing the strategy of embarrassing the offi

-

cers of the company or of the banks it did business with—as well as us

-

ing the economic power of pension funds.

10

The campaign was partly designed and organized with the help of

Roy Rogers, a new type of consultant who takes credit for developing

the concept of the corporate campaign. “In effect, Rogers began by iden

-

tifying all of the key stakeholder relationships of the target company,

assessing the strengths and weaknesses of each, and devising ways to

exploit the weaknesses.”

11

For example, one tactic was to force the resig

-

nation of some of J. P. Stevens’s directors. Among them were James

Finley, Stevens’s chairman, who resigned from the board of New York

Life, and the chairman of Avon Products, who resigned from both the

Manufacturers Hanover board and the board of Stevens. Another tactic

was the use of shareholder resolutions and demonstrating at Stevens’s

annual meeting.

Anticorporate Campaigns

Labor unions were not the only adversaries of corporations. As Manheim

documents, nonlabor entities launched 29 anticorporate campaigns be-

tween 1989 and 1999. Some better known ones are these:

• BP Amoco: Greenpeace seeks to halt offshore oil development on

Alaska’s North Slope.

• Conoco: Rainforest Action Network pressured the company to

cease operations in the Amazon region.

• DuPont: Greenpeace wanted the company to stop using ozone-de-

stroying chemicals.

• Freeport-McMoRan: Rainforest Action Network and Project Un

-

derground launched an effort to force the company to stop opera

-

tions said to threaten indigenous Indonesian tribes.

• Hoechst/Rhone Poulenc: Fund for the Feminist Majority sought to

speed U.S. availability of RU-486, the day-after birth control pill.

• Monsanto: Greenpeace attempted to dissuade the company from

engaging in genetic engineering.

• Shell: Targeted by Project Underground for doing business in Nigeria.

• Siemens: Global 2000 and Friends of the Earth aimed to force the

company to cease upgrading and operating nuclear power facili

-

ties in Russia, Eastern Europe, and elsewhere.

12

This list can be vastly extended when a broader range of confronta

-

tions between social action groups and corporations are considered. A

chapter on confrontation crises refers to the more than 200 national

40 I CHAPTER 2

boycotts held in 1990 alone and reviews such confrontations as the Nat

-

ural Resources Defense Council’s crusade against McDonald’s use of

hard-to-recycle plastic foam food containers and the long-lasting boy

-

cott of South Africa during the apartheid era. Case studies include the

PUSH (People United to Save Humanity) boycott of Nike for not doing

more to help the African American community and the classic demand

from FIGHT (Freedom, Integration, God, Honor—Today) of Eastman

Kodak to train and hire more African Americans.

13

When a corporation is targeted by a labor union or social action

group, it has two major choices: (a) seek to contain the issue, which is

the traditional approach; and (b) seek to engage the challenging group,

an option that is gaining in acceptance.

CONTAINMENT STRATEGIES

The most compelling strategy for a company facing an emerging issue is

to contain it—to prevent it from building up social energy and progress-

ing to the next life cycle stage where it receives media and public sup-

port. To contain or resolve an issue, a company limits its target to

individuals and groups that present or promote an idea, or air a griev-

ance and press demands. To use mass communication media would be

counterproductive because the public would become aware of the issue

in question and support for it would thereby grow. If this were to occur,

the issue would have reached the second stage of the life cycle—the stage

of public involvement—and be on the public agenda.

This containment strategy is analogous to the handling of a rumor.

Assuming that a rumor is not widespread, efforts to counter it are re-

stricted to people who presumably already have heard it. To hold a news

conference, send out news releases, or place an advocacy ad would sim-

ply spread the rumor further and do even more damage. Thus, when

McDonald’s heard a rumor that it ground red worms into its ham-

burger meat, the company limited its response to the store where the

rumor started. It took out an ad in the local paper, saying only that Mc

-

Donald’s hamburgers are made of 100% beef, implying that worms

could not possibly be part of that 100% beef product.

14

In a rumor situation, the mass media should be avoided entirely.

This may not be possible, however, if a local newspaper or broadcast

station has reported the rumor. In such an eventuality, factual infor

-

mation should be supplied only to those specific media. Management

runs the risk, of course, that the wire services or alert national media

may pick up the story. A prudent organization will, therefore, prepare

a news release for such a contingency but not send the news release or

hold a news conference. The case study in Box 2.1 adapted from the

Harvard Business Review illustrates the factors that must be considered

in such a situation.

Both judgment and research are required to determine whether a con

-

tainment strategy will succeed. Reporters and editors, as well as public re

-

INTEREST GROUP STRATEGIES I 41