Kristiansen Svein. Maritime Transportation: Safety Management and Risk Analysis

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Mackworth (1946) made one of the early studies of the temperature effect on

monitoring tasks as shown in Figure 11.6. It can be seen that the number of monitoring

mistakes starts to increase sharply above an effective temperature of 30

C. This

corresponds to the upper limit for what is experienced as comfortable.

Obviously the question of acceptable temperature is also related to the duration of

exposure. As shown in Figure 11.7, the duration of unimpaired mental performance

decreases quickly as the effective temperature rises above 30

C (Wing, 1965).

Finally, it should be mentioned that there seems to be a special combined effect of

warmth and sleep loss (Pepler, 1959). Observed phenomena are reduced performance in

tracking tasks and gaps in serial responses. Simply stated, the following mechani sms are

seen: ‘Warmth reduces accuracy’ whereas ‘Sleep loss reduces activity’.

Ta b l e 11 . 4 . Thermal climate factors on vessels

Section Situation Solution

Living quarters Reasonable control Ventilation and air conditioning is

standard

Navigation bridge Thermal control up to 22–28

C

Heat sources: large window panes,

electronic equipment and open

doors

Ventilation and air conditioning is

standard

Galley A number of heat sources: stove, etc. Improved isolation of heat sources

Long periods above thermal comfort

criteria

Engine rooms Air cooling of engines

Temperature often 10–20

higher

than outside temperature

Heat radiation from hot surfaces

Heavy repair and maintenance work

High relative humidity in smaller,

confined spaces

Work in engine rooms will in general

take place well outside thermal

comfort criteria

Under winter conditions large

temperature variations within

the same space

Cargo tanks Inspections and final cleaning

operations may be stressing in

hot outside climate. Protective

clothing may contribute to

the stress

Cleaning by permanently installed

equipment

On deck Both high and low temperatures

depending on time of the year

and geographical latitude

Sun radiation

Clothing and protection

Effect of wind (air speed) under

winter conditions

326 CHAPTER 11 HU MAN FA CT ORS

11.7.3 Noise

The primary noise sources onboard are: main engine, propeller, auxiliary engines and

engine ventilation. The noise (or unwanted sound) is measured in terms of sound intensity

and expressed as dB(A). Table 11.5 summarizes maximum recorded and recommended

noise levels for the main ship sections.

11 .7.4 Infrasound

Infrasound is acou stic waves below 20 Hz that are not audible by the human ear. It has,

however, been found that for high intensities infrasound has negative effects on the human

in terms of reduced well-being, tiredness and increased reaction time.

The relation between infrasound and possible negative effect is still only partly

understood. It has been suspected that even higher intensities (above 100 dB) may have

adverse effect on control of balance, disturbance of vision and choking.

Figure 11.6. Monitoring mistakes as a function of effective temperature. (Source: Mackworth,1946.)

Figure 11.7. Upper limit for unimpaired mental performance. (Source: Wing,1965.)

11 .7 PHYSICAL WORK ENVIRONMENT 327

Typical ranges for infrasound measured on vessels are 4 Hz (55 dB) to 16 Hz (95 dB).

The fact that infrasound is present both on the bridge and in the engine control room

may pose a problem to safe operation.

11.7. 5 Vibr ation

Vibration is seen by a significant part of the crew as one of the most disturbing

environmental factors onboard. This is partly explained by the fact that it is experienced

both at work and off-duty. This means that persons affected are given no opportunity

for restitution during free hours. Vibration is expressed by acceleration (m/s

2

)in

selected frequency bands (Hz). Vibrations are usually measured for a range from 0.5 Hz

to 125 Hz.

The main sources of vibration are the main engine and the propeller. The induced

vibrations are further transmitted through the steel hull and deck houses. High

superstructures are further subject to resonance phenomena. It is also experienced in

the aft part as an effect of the hogging–sagging movement of the hull girder, giving very

low frequency resonance (0.5 Hz).

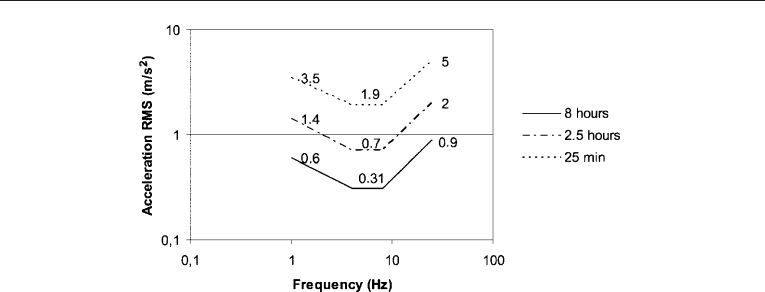

ISO has given norm values for exposure (time) versus vibration, both with respect

to ‘reduced work performance’ and ‘reduced comfort’. Figure 11.8 illustrates the

Ta b l e 11. 5 . Noise in vessels

Section Situation Solution

Living quarters Highest values: dB(A) ¼58–70

Depends mainly on the distance to

engine rooms

Variation with ship type

28% experienced the noise

as troublesome

Navigation bridge Highest values: dB(A) ¼65–73 Lowest noise levels on vessels with

bridge in the fore part

(passenger, Ro-Ro)

Some effect on direct communication

and use of internal communication

equipment

Galley Mean value: dB(A) ¼71–77

Recommended value 65 dB(A) is exceeded

due to the background noise

Engine rooms Highest values: dB(A) ¼93–113 Wear ear protection

Recommended value: 100 dB(A)

Factors: power, engine type

Sectioning of engine room

Risk of physiological damage

(reduced hearing)

50% of engine personnel report the

noise as troublesome

328 CHAPTER 11 HU MAN FA CT ORS

ISO norm for maintaining profiency. It can be seen that the most sensitive frequency

area is roughly 4–8 Hz. For longer durations the vertical acceleratio n should not exceed

0.31 m/s

2

.

Measurements of vibrations by Iverga

˚

rd et al. (1978) can be summarized as foll ows:

. Navigati on bridge: Most vessels have a vibration level below recommended values.

The exception is tankers. However, crew reports some discomfort.

. Engine room: Most observations lie between the comfort and performance curves.

Although the comfort limit is not exceeded, personnel reports problems due to the

reduced opportunity for restitution during the free watch.

. Cabin area: Vibration level coincides with comfort line in the critical area 8–16 Hz.

Confirms that restitution becomes a problem.

11. 8 EF F EC T OF SEA MOTION

One of the classical torments of life at sea is the so-called seasickness that may affect both

passengers an d crew. The more correct term is motion sickness as it is present in different

transport modes and in certain other situations. Motion sickness may be experienced

during anything from riding a camel, operating a microfic he reader to viewing an IMAX

movie. How strongly one may be affected differs, but it usually involves stomach

discomfort, nausea, drowsiness and vomiting, to mention a few.

The problem has recently been surveyed by Steven s and Parson s (2002) in a maritime

context. As the authors point out, one of the consequences of seasickness is less motivation

and concern for the safety critical tasks onboard. However, for the majority of persons

there will be an adaption to sea motion over time so that the sickness fades away after a

few days. There is also some comfort in the fact that susceptibility usually decreases with

increasing age. The effect of moti on appears sometimes in the form of the sopite syndrome,

which is less dramat ic and usually only experienced as drowsiness and mental depression.

Figure 11.8. Vibration tolerance limits as function of exposure time. (Adapted from ISO 2631,1985.)

11.8 EFFECT OF SEA MOTION 329

This affection may also be safety critical in the sense that it has an effect on performance

and is not always evident to the subject.

Various explanations of motion sickness have been proposed, but contemporary

theory points to the conflict or mismatch between the organs that sense motion:

. Vestibular system in the inner ear: semicircular canals that respond to rotation and

otoliths that detect translational forces.

. The eyes (vision system) that detect relative motion between the head and the

environment as the result of motion of either or both.

. The proprioceptive (somatosensory) system involves sensors in body joints and muscles

that detect movement or forces.

The theory assumes that under normal situations the three systems detect

the movements in an unambiguous way. However, under certain conditions the senses

give conflicting signals that lead to motion sickness. A typical maritime scenario is

experiencing sea motion inside the vessel without visual reference to sea, horizon or land

masses. In this case the vestibular detects motion in the absence of visual reference.

Watching the waves from the ship may give rise to conflict between vision and vestibular

system.

Extensive experiments in motion simulators found that subjects were primarily

sensitive to vertical motion (heave) and that maximum sensitivity occurred at a frequency

of 0.167 Hz (Griffin, 1990). Given the fact that the principal vertical frequency in the sea

motion spectre is 0.2 Hz, the occurrence of seasickness is understandable. There are

two methods for estimation of motion sickness: Motion Sickness Incidence (MSI) and

Vomiting Incidence (VI). Both methods are outlined by Stevens and Parsons (2002). There

are a number of effects of seasickness:

. Motivational: drowsiness and apathy

. Motion-induced fatigue (MIF): reduced mental capacity and performance

. Reduced physical capacity

. Added energy expenditure to counterbalance motion

. Sliding, stumbling and loss of balance

. Some interference with fine motor co ntrol tasks

The effect on cognitive tasks is more inconclusive as it has been difficul t to isolate the

effect of physical stress. Another problem is the fact that bridge tasks involve a number

of cognitive processes and skills which may be influenced differently by the sea motion

(Wertheim, 1998).

In order to minimize the risk of seasickness, it is necessary to establish operational

criteria. Baitis et al. (1995) point out that it is not the roll angle in itself that lim its the

operation but rather the vertical and lateral accelerations associated with them. Table 11.6

shows the criteria proposed by NATO (NATO STANAG 4154, 1997), which are based on

both earlier and recent principles. An alternative set of criteria make a distinction between

330 CHAPTER 11 HU MAN FA CT O RS

different ship types (NORDFORSK, 1987) as summarized in Table 11.7. It can, however,

be concluded that the two sets of criteria agree fairly well.

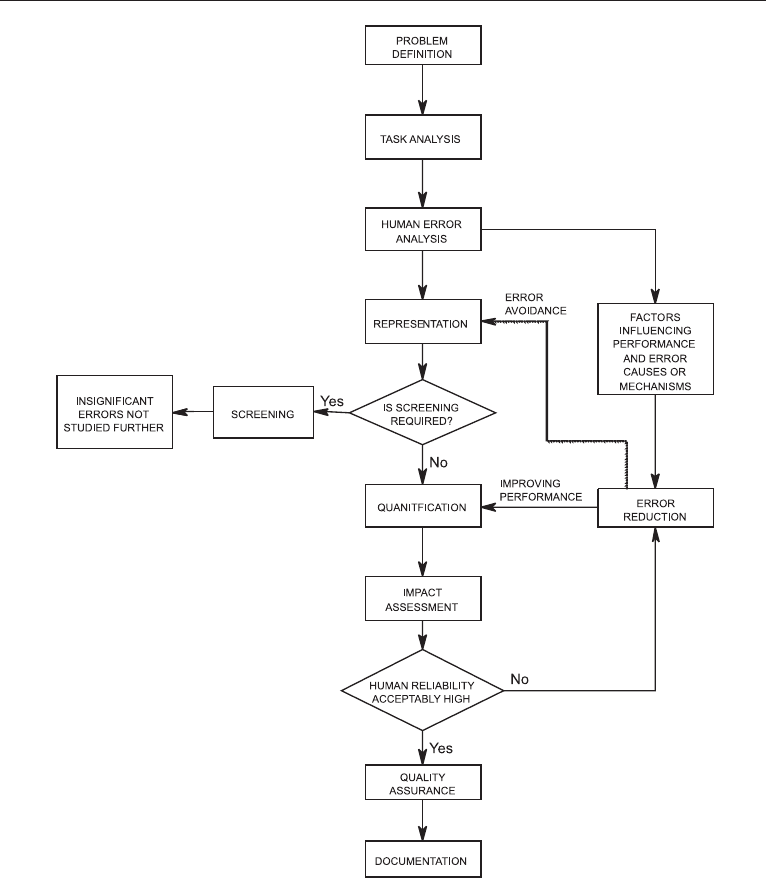

1 1.9 H UMAN RELIABILITY ASSESSMENT

Risk analysis involves making quantitative estimates of the risk associated with designs

and operations. Typical is estimation of the probability of having specified accident events

by means of fault tree analysis (FTA) or event tree analysis (ETA). In order to make

realistic estimates, human-error-related events must be incorporated. This is not a trivial

problem given our limited understanding of this phen omenon and lack of systematic data.

Despite this, various approaches have been developed and to some degree have also

been supplemented with quantitative data. The objective of human reliability assessment

(HRA) has been stated as follows by Kirwan (1992a, 1992b):

1. Human error identification: what can go wrong?

2. Human error qua ntification: how often will it occur?

3. Human error reduction: how can it be prevented or the impact reduced?

The key methodological steps are outlined in Figure 11.9.

Considerable experience has been accumulated with the so-called first-generation

HRA methods, primarily from applications in the process and nuclear industries.

However, they have come under increasing attack from cognitive scientists who point

to the fundamental lack of ability to model human behaviour in a realistic manner

(Hollnagel, 1998).

Ta b l e 11. 7. General bridge operability criteria for ships

Merchant ships Naval vessels Fast small craft

Vertical acceleration (RMS) 0.15 g 0.2 g 0.275 g

Lateral acceleration (RMS) 0.12 g 0.1 g 0.1 g

Roll (RMS) 6.0

4.0

4.0

Source: NORDFORSK (1987).

Table 11.6. Sea motion operability criteria

Motion sickness incidence (MSI) 20% of crew in 4 hours

Motion-induced interruption (MII) 1 tip per minute

Roll amplitude 4.0

RMS

Pitch amplitude 1.5

RMS

Vertical acceleration 0.2 g RMS

Lateral acceleration 0.1 g RMS

Source: NATO STANAG 4154 (1997). RMS, root mean square; g, acceleration of gravity.

11.9 H UMAN RELIABI L ITYASSESSM ENT 331

11.9.1 Th er p

The Technique for Human Error Rate Predict ion (THERP) is probably the best-known

and most widely used technique of human reliability analysis. The main objective of

THERP is to provide human reliability data for probabilistic risk and safety assessment

Figure 11.9. Human reliability assessment steps (Kirwan,1992a,1992b).

332 CHAPTER 11 HU MAN FA CT ORS

studies. The methods and underlying principles of THERP were developed by Swain and

Guttmann (1983) and are often referred to as the THERP Handbook.

The methodological steps are:

1. Identify system failures of interest: This stage involves identifying the system functions

that may be influenced by human errors and for which error probabilities are to be

estimated.

2. Analyse related human operations: This stage includes performing a detailed task

analysis and identifying all significant interactions involving personnel. The main

objective of this stage is to create a model that is appropriate for the quantification

in stage 3.

3. Estimate the human error probabilities: In this stage the human error probabilities

(HEPs) are estimated using a combination of expert judgements and available data.

4. Determine the effect on system failure events: Estimating the effect of human errors

on the system failure events is the main task of this stage. This usually involves

integration of the HRA with an overall risk/safety assessment (i.e. PRA/PSA).

5. Recommend and evaluate changes: In this stage changes to the system under

consideration are recommended and the system failure probability recalculated.

Possible solutions for various human factors problems include job redesign,

implementation of mechanical interlocks, administrative control s, and implementa-

tion of training and certification requirements.

The probability of a specific erroneous action is given by the following expression:

P

EA

¼ HEP

EA

X

m

k¼1

PSF

k

W

k

þ C

where:

P

EA

¼ Probability of an error for a specific action

HEP

EA

¼ Basic (nominal) operator error probability of a specific action

PSF

k

¼ Numerical value of kth performance shaping factor

W

k

¼ Weight of PSF

k

(numerical constant)

C ¼ Numerical constant

m ¼ Number of PSFs

The probability is a function of the error probability for a generic task modified

by relevant performance shaping factors. The basic HEPs can be looked up in 27

comprehensive tables in the THERP Handbook (Swain and Guttmann, 1983). The PSFs

are tabulated in the same fashion. The three sets of PSFs are shown in Table 11.8.

The modelling of relevant human actions in event trees is based heavily on the task

analysis performed in stage 1. In the present stage a more detailed analys is is carried out

11.9 H UMAN RELIABI L ITYASSESSM ENT 333

Ta b l e 11 . 8 . PSFs inTHERP

Situational

characteristics

Architectural features

Temperature

Humidity

Air quality

Lighting

Noise and vibration

Degree of general cleanliness

Work hours and work breaks

Availability of special equipment

Adequacy of special equipment

Shift rotation

Organizational structure

Adequacy of communication

Distribution of responsibility

Actions made by co-workers

Rewards, recognition and benefits

Job and task

instructions

Procedures required (written or not) Work methods

Cautions and warning Plant policies

Written or oral communication

Task and equipment

characteristics

Perceptual requirements Frequency of repetitiveness

Motor requirements (speed,

strength, etc.)

Control–display relationships

Anticipatory relationships

Interpretation

Decision-making

Complexity (information load)

Narrowness of task

Task criticality

Long- and short-term memory

Calculation requirements

Feedback (knowledge of results)

Dynamics vs. step-by-step activities

Team structure and communication

Man–machine interface

Psychological

stressors

Suddenness of onset Long, uneventful vigilance periods

Duration of stress Conflicts about job performance

Task speed Reinforcement absent or negative

High jeopardy risk Sensory deprivation

Threats (of failure, of losing

job, etc.)

Distractions (noise, flicker,

glare, etc.)

Monotonous and/or

meaningless work

Inconsistent cueing

Physiological

stressors

Duration of stress Atmospheric pressure extremes

Fatigue Oxygen insufficiency

Pain or discomfort Vibration

Hunger or thirst Movement constriction

Temperature extremes Lack of physical exercise

Radiation Disruption of circadian rhythm

G-force extremes

Organism factors Previous training/experience Emotional state

State of current practice or skill Sex differences

Personality and intelligence variables Physical condition

Motivation and attitudes

Knowledge required

Stress (mental or bodily tension)

Attitudes based on external

influences

Group identification

334 CHAPTER 11 HU MAN FA CT ORS

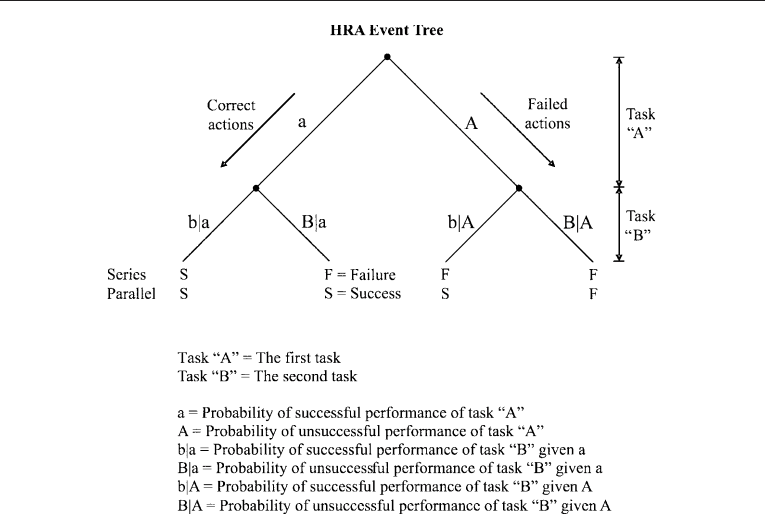

on each of the relev ant human actions identified and a comprehen sive description of the

performance characteristics is made. Each human/operator action is divided into tasks

and subtasks, and these are then represented graphically in a so-called HRA event tree

(Figure 11.10).

HRA event trees model performance in a binary fashion, i.e. as being either a success

or a failure. Branches in a HRA event tree show different human activities, and the

values assigned to all human activities represented by the branches (except those in the

first branching) are conditional probabilities. Figure 11.11 illustrates a simple HRA

event tree (Swain and Guttmann, 1983). As can be seen from this figure, it is common

to present the correct actions on the left-hand side of the tree and failures on the

right-hand side.

11.9. 2 Cri t icis m o f th e HR A A pp r o a c h e s

It was commented above that the binary categorization of human erroneous actions

used in HRA event trees may be too simple to make any claim on psychological realism

(Hollnagel, 1998). First of all there is an important difference between failing to

perform an action and failing to perform it correctly. Furtherm ore, the HRA event tree

approach fails to recognize that an action may happen in many different ways and for

different reasons.

Figur e 11.10. HRA event tree for two successive subtasks.

11.9 H UMAN RELIABI L ITYASSESSM ENT 335