Klir G.J. Uncertainity and Information. Foundations of Generalized Information Theory

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

382 9. METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES

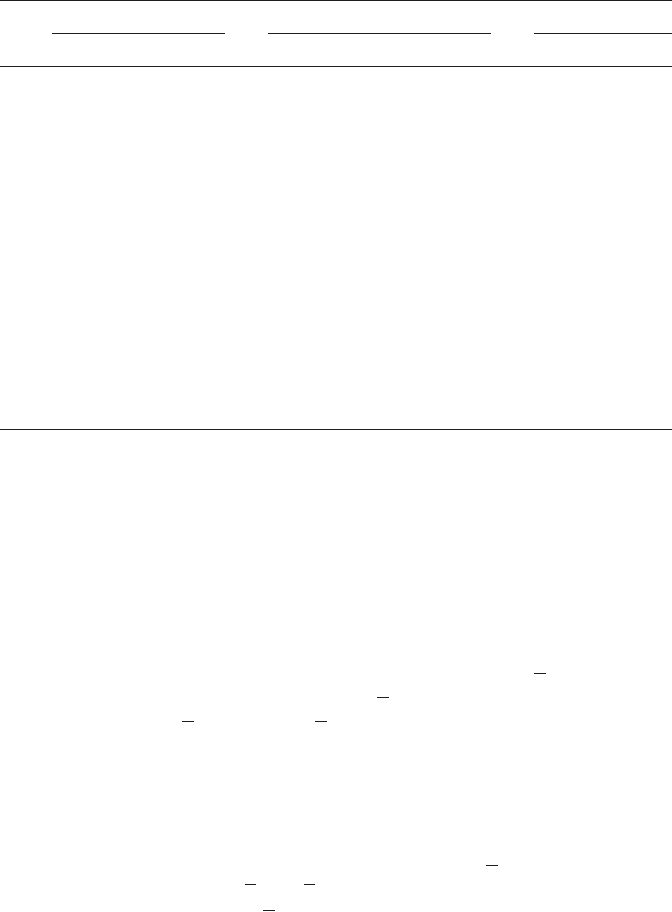

Table 9.7. Illustration to Example 9.9

States x

1

x

2

x

3

s

0

000

s

1

001

s

2

010

s

3

011

s

4

100

s

5

101

s

6

110

s

7

111

(a)

x

1

x

2

R

12

(x

1

, x

2

) x

2

x

3

R

23

(x

2

, x

3

) x

1

x

3

R

13

(x

1

, x

3

)

0 0 1.0 0 0 0.5 0 0 0.9

0 1 0.8 0 1 1.0 0 1 1.0

1 0 0.6 1 0 0.7 1 0 1.0

1 1 0.0 1 1 0.4 1 1 0.3

(b)

x

1

x

2

x

3

ER

12

x

1

x

2

x

3

ER

23

x

1

x

2

x

3

ER

13

0 0 0 1.0 0 0 0 0.5 0 0 0 0.9

0 0 1 1.0 1 0 0 0.5 0 1 0 0.9

0 1 0 0.8 0 0 1 1.0 0 0 1 1.0

0 1 1 0.8 1 0 1 1.0 0 1 1 1.0

1 0 0 0.6 0 1 0 0.7 1 0 0 1.0

1 0 1 0.6 1 1 0 0.7 1 1 0 1.0

1 1 0 0.0 0 1 1 0.4 1 0 1 0.3

1 1 1 0.0 1 1 1 0.4 1 1 1 0.3

(c)

x

1

x

2

x

3

Cyl

0 0 0 0.5

0 0 1 1.0

0 1 0 0.7

0 1 1 0.4

1 0 0 0.5

1 0 1 0.3

1 1 0 0.0

1 1 1 0.0

(d)

9.4. PRINCIPLE OF REQUISITE GENERALIZATION

GIT, as an ongoing research program, offers us a steadily growing inventory

of diverse uncertainty theories. Each of the theories is a formal mathematical

system, which means that it is subject to some specific assumptions that are

inherent in its axioms. If these assumptions are violated in the context of a

given application, the theory is ill-suited for the application.

The growing diversity of uncertainty theories within GIT makes it increas-

ingly more realistic to find an uncertainty theory whose assumptions are in

harmony with each given application. However, other criteria for choosing a

suitable theory are often important as well, such as low computational com-

plexity or high conceptual transparency of the theory.

Due to the common properties of uncertainty theories recognized within

GIT, emphasized especially in Chapters 4, 6, and 8, it is also feasible to work

within GIT as a whole. In this case, we would move from one theory to another

as needed when dealing with a given application. There are basically two

reasons for moving from one uncertainty theory to another:

1. The theory we use is not sufficiently general to capture uncertainty that

emerges at some stage of the given application. A more general theory

is needed.

2. The theory we use becomes inconvenient at some stage of the given

application (e.g., its computational complexity becomes excessive) and

it is desirable to replace it with a more convenient theory.

These two distinct reasons for replacing one uncertainty theory with

another lead to two distinct principles that facilitate these replacements: a

principle of requisite generalization, which is introduced in this section, and a

principle of uncertainty invariance, which is introduced in Section 9.5.

The following is one way of formulating the principle of requisite general-

ization:Whenever,at some stage of a problem-solving process involving uncer-

tainty, a given uncertainty theory becomes incapable of representing emerging

uncertainty of some type, it should be replaced with another theory, sufficiently

more general, that is capable of representing this type of uncertainty. As

suggested by the name of this principle, the extent of generalization is not

optional, but requisite, determined by the nature of the emerging uncertainty.

It seems pertinent to compare the principle of requisite generalization with

the principle of maximum uncertainty. Both these principles clearly aim at

an epistemologically honest representation of uncertainty. The difference

between them, a fundamental one, is that the former principle applies to GIT

as a whole, while the latter applies to each individual uncertainty theory within

GIT.

The principle of requisite generalization is introduced here for the first time.

There is virtually no experience with its practical applicability. At this point,

the best way to illustrate it seems to be to describe some relevant examples.

9.4. PRINCIPLE OF REQUISITE GENERALIZATION 383

EXAMPLE 9.10. Consider two variables, v

1

, v

2

, each of which has two possi-

ble states, 0 and 1. For convenience, let the joint states of the variables be

labeled by an index i, as defined in Table 9.8a. Assume that we work within

classical probability theory.Assume further that we have a record of an appre-

ciable number of observations of the variables. Some of the observations

contain a value of both variables, some of them contain a value of only one

variable due to some measurement or communication constraints (not essen-

tial for our discussion). When only one variable is observed, it is known that

this observation represents one of two joint states of the variable, but it is not

known which one it actually is. For example, observing that v

1

= 1 (and not

knowing the state of v

2

) means that the joint state may be i = 2 or i = 3, but

we do not know which of them is the actual joint state. There are basically

three ways to handle these incomplete data:

(i) We can just ignore all the incomplete observations. This means,

however, that we ignore information that may be useful, or even

crucial, in some applications.

(ii) We can apply the principle of maximum entropy to fill any gaps in the

data.This results in a particular probability measure, which is obtained

by uniformly distributing the uncertain observations in each pair of

relevant states. Using this principle allows us to stay in probability

theory (and it is epistemologically the best way to deal with incom-

384 9. METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES

Table 9.8. Three Ways of Handling Incomplete Data

(Example 9.10)

v

1

v

2

i

000

011

102

113

(a)

i:0123N(A) Pro

1

(A) Pro

2

(A) m(A) Bel(A) Pl(A)

A: 1 0 0 0 106 0.546 0.369 0.106 0.106 0.632

0 1 0 0 55 0.284 0.237 0.055 0.055 0.419

0 0 1 0 25 0.129 0.246 0.025 0.025 0.467

0 0 0 1 8 0.041 0.148 0.008 0.008 0.288

1 1 0 0 121 0.830 0.606 0.121 0.373 0.839

1 0 1 0 314 0.675 0.615 0.314 0.445 0.785

0 1 0 1 152 0.325 0.385 0.152 0.215 0.555

0 0 1 1 128 0.170 0.394 0.128 0.161 0.627

(b)

plete data within probability theory), but the use of the uniform dis-

tribution is totally arbitrary (imposed only by the axioms of probabil-

ity theory) and does not represent the actual uncertainty in this case.

(iii) We can apply the principle of requisite generalization and move from

probability theory to Dempster–Shafer theory (DST), which is suffi-

ciently general to represent the actual uncertainty in this case. Observ-

ing a state of one variable only is easily described in DST as observing

a set of two joint states. For example, observing that v

1

= 1 (and not

knowing the state of v

2

) can be viewed as observing the subset {2, 3}

of the four joint states. In this way, uncertainty is represented fully and

accurately.

A numerical example illustrating the three options is shown in Table 9.8b.

It is assumed that we have a record of 1000 observations of the variables, some

containing values of both variables and some containing a value of only one

of the variables. Listed in the table are only subsets A of joint states that are

supported by observations (these are also all focal elements of the represen-

tation in DST). Symbols in the table have the following meanings:

N(A): The number of observations of the relevant subsets A of the joint

sets.

Pro

1

(A): Values of the probability measure based on ignoring incomplete

observations.

Pro

2

(A): Values of the probability measure derived by the maximum

entropy principle.

m(A):Values of the basic probability assignment function in DST, based on

the frequency interpretation.

Bel(A) and Pl(A):Values of the associated belief and plausibility measures,

respectively.

We can see that DST is the right (or requisite) generalization in this

example. It is capable of fully representing both types of uncertainty that are

inherent in the given evidence. No further generalization is needed. The prob-

abilistic representation derived by the principle of maximum entropy is not

capable of capturing nonspecificity, and hence, it is not a full representation of

uncertainty in this case.

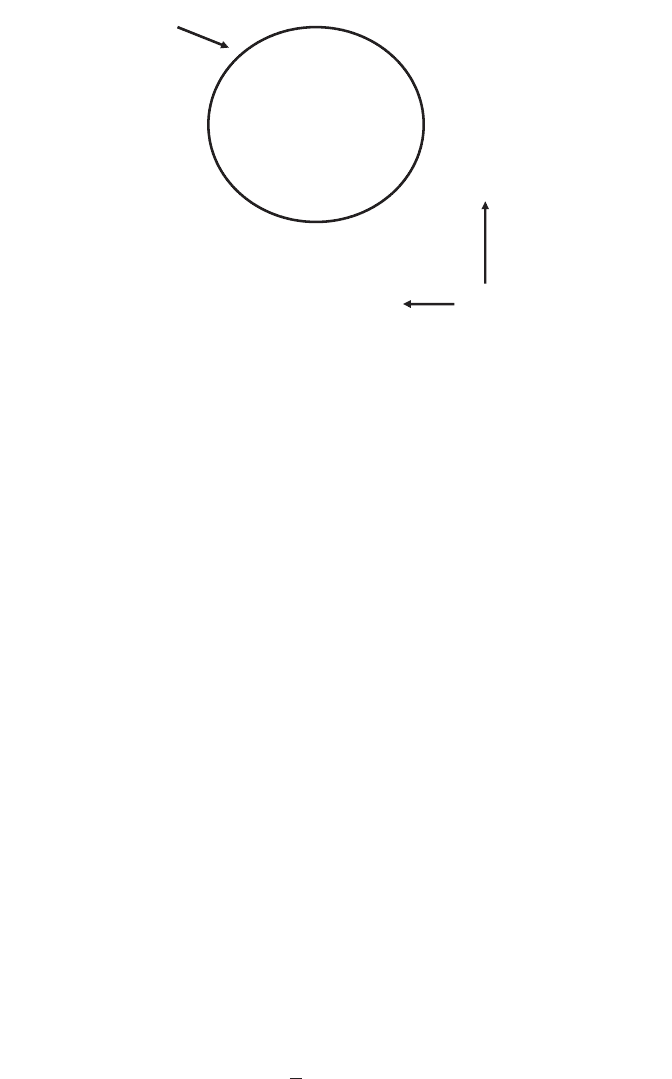

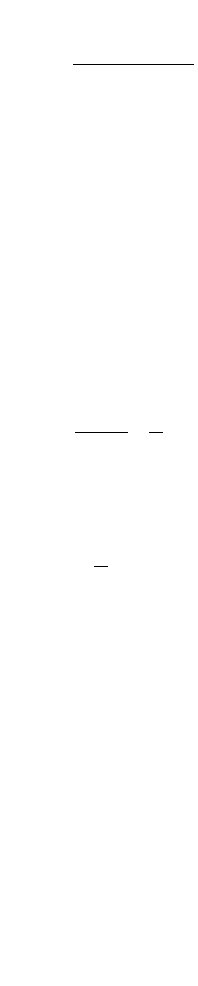

EXAMPLE 9.11. Consider the simplest possible marginal problem in proba-

bility theory, which is depicted in Figure 9.7: given marginal probabilities on

the two-element sets, what are the associated joint probabilities? This ques-

tion can be answered in two very different ways, depending on whether it is

required or not required to remain in probability theory. If it is required, then

we need to determine one particular joint probability distribution function.

The proper way to do that (as is explained in Section 9.3) is to use the prin-

9.4. PRINCIPLE OF REQUISITE GENERALIZATION 385

ciple of maximum entropy. From subadditivity and additivity of the Shannon

entropy, it follows immediately that the maximum-entropy joint probability

distribution function p is the product of the given marginal probability distri-

bution functions. That is, using the notation introduced in Figure 9.7,

For the numerical values given in Figure 9.7, we get p

11

= 0.48, p

12

= 0.32,

p

21

= 0.12, and p

22

= 0.08.

If it is not required that we remain in probability theory, we should apply

the principle of requisite generalization and move to another theory of uncer-

tainty that is sufficiently general to capture the full uncertainty in this problem.

The full uncertainty is expressed in terms of the set of all joint probability dis-

tributions that are consistent with the given marginal probability distributions.

Here we can utilize Example 4.3, in which this set is determined. The follow-

ing is its formulation for the numerical values in Figure 9.7:

From this set of joint probability distributions, we can derive the associated

lower and upper probabilities, and m

¯

, and the Möbius representation,

which are shown in Table 9.9. The monotone measure representing lower

m

p

pp

pp

pp

11

12 11

21 11

22 11

0406

08

06

04

Œ

[]

=-

=-

=-

.,.

.,

.,

..

ppxpy ij

ij j

=

()

◊

()

=

1

12for , , .

386 9. METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES

p

11

p

12

••

x

1

•

p

(

x

1

)

p

21

p

22

••

x

2

•

p

(

x

2

)

y

1

y

2

••

p

(

y

1

)

p

(

y

2

) Given

Example

:

p

(

x

1

) = 0.8,

p

(

x

2

) = 0.2

p

(

y

1

) = 0.6,

p

(

y

2

) = 0.4

?

Figure 9.7. The marginal problem in probability theory (Example 9.11).

probabilities is superadditive, but it is not 2-monotone (there are eight viola-

tions of 2-monotonicity pertaining to subsets with these elements). Hence, to

fully represent uncertainty in this example, we need to move to the most

general uncertainty theory. This is requisite, not a matter of choice.

9.5. PRINCIPLE OF UNCERTAINTY INVARIANCE

The multiplicity of uncertainty theories within GIT has opened a new area of

inquiry—the study of transformations between the various uncertainty theo-

ries. The primary motivation for studying these transformations stems from

questions regarding uncertainty approximations. How to approximate, in a

meaningful way, uncertainty represented in one theory by a representation in

another, less general theory? From the practical point of view, uncertainty

approximations are sought to reduce computational complexity or to make

the representation of uncertainty more transparent to the user. From the the-

oretical point of view, studying uncertainty approximations enhances our

understanding of the relationships between the various uncertainty theories.

In this section, all uncertainty approximation problems are expressed in

terms of one common principle, which is referred to as the principle of uncer-

tainty invariance.To formulate this principle,assume that T

1

and T

2

denote two

uncertainty theories such that T

2

is less general than or incomparable to T

1

.

Assume further that uncertainty pertaining to a given problem-solving situa-

tion is expressed by a particular uncertainty function u

1

, and that this function

is to be approximated by some uncertainty function u

2

of theory T

2

. Then,

9.5. PRINCIPLE OF UNCERTAINTY INVARIANCE 387

Table 9.9. Illustration of the Principle of Requisite Generalization (Example 9.11)

x

1

x

1

x

2

x

2

m

¯

(A) m

¯

(A) m(A) Pro(A)

y

1

y

2

y

1

y

2

A: 0 0 0 0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0

1 0 0 0 0.4 0.6 0.4 0.48

0 1 0 0 0.2 0.4 0.2 0.32

0 0 1 0 0.0 0.2 0.0 0.12

0 0 0 1 0.0 0.2 0.0 0.08

1 1 0 0 0.8 0.8 0.2 0.80

1 0 1 0 0.6 0.6 0.2 0.60

1 0 0 1 0.4 0.8 0.0 0.56

0 1 1 0 0.2 0.6 0.0 0.44

0 1 0 1 0.4 0.4 0.2 0.40

0 0 1 1 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.20

1 1 1 0 0.8 1.0 -0.2 0.92

1 1 0 1 0.8 1.0 -0.2 0.88

1 0 1 1 0.6 0.8 -0.2 0.68

0 1 1 1 0.4 0.6 -0.2 0.52

1 1 1 1 1.0 1.0 0.4 1.00

according to the principle of uncertainty invariance, it is required that the

amounts of uncertainty contained in u

1

and u

2

be the same. That is, the trans-

formation from T

1

to T

2

is required to be invariant with respect to the amount

of uncertainty.This explains the name of the principle. Due to the unique con-

nection between uncertainty and uncertainty-based information, the principle

may also be viewed as a principle of information invariance or information

preservation. It seems reasonable to compare this principle, in a metaphoric

way, with the principle of energy preservation in physics.

The following are examples of some obvious types of uncertainty approxi-

mations, some of which are examined in this section:

•

Approximating belief measures by probability measures, measures of

graded possibilities, l-measures, or k-additive measures.

•

Approximating probability measures by measures of graded possibilities

and vice versa.

•

Approximating measures of graded possibilities by crisp possibility

measures.

•

Approximating k-monotone measures (k finite) by belief measures.

•

Approximating 2-monotone measures by measures based on reachable

interval-valued distributions.

•

Approximating fuzzified measures of some type by their crisp

counterparts.

Observe that in virtually all these approximations, the principle of uncer-

tainty invariance can be formulated in terms of the total aggregated uncer-

tainty, S

¯

, or in terms of one or both on its components, GH and GS. These

variants of the principle lead, of course, to distinct approximations. Their

choice depends on what type of uncertainty we desire to preserve in each

application.

Preserving the amount of uncertainty of a certain type need not be the only

requirement employed in formulating the various problems of uncertainty

approximation. Other requirements may be added to the individual formula-

tions in the context of each application.A common requirement is that uncer-

tainty function u

1

can be converted to its counterpart u

2

by an appropriate

scale, at least ordinal.

In the rest of this section, only some of the approximation problems are

examined and illustrated by specific examples. This area is still not sufficiently

developed to warrant a more comprehensive coverage.

9.5.1. Computationally Simple Approximations

Assume that the measure of uncertainty employed in the principle of uncer-

tainty invariance is the functional S

¯

. Then, all uncertainty approximations in

which a given uncertainty function u

1

is to be approximated by a probability

388 9. METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES

measure u

2

are conceptually trivial and computationally simple. Just recall

that when we calculate S

¯

(u

1

) by Algorithm 6.1 (or in any other way), we obtain,

as a by-product, a probability distribution function for which the Shannon

entropy is equal to S

¯

(u

1

).This probability distribution function is thus the prob-

abilistic approximation of the uncertainty function u

1

based on the principle

of uncertainty invariance and the use of functional S

¯

.

EXAMPLE 9.12. Consider the lower and upper probabilities and m

¯

, defined

in Table 9.10. It can be easily checked that is a l-measure for l = 5. Apply-

ing Algorithm 6.1 to , we obtain S

¯

() = 1.971 and, as a by-product, the prob-

ability distribution

Probability measure Pro based on this distribution (also shown in Table 9.10)

thus can be viewed as a probabilistic approximation of for which

Although probabilistic approximations based on invariance of the aggregated

total uncertainty S

¯

are computationally simple, their utility is questionable due

to the notorious insensitivity of this uncertainty measure. When either GH or

GS is employed instead of S

¯

, then, clearly, these approximations must be

handled differently, as is illustrated in the next section.

SS Sm

()

=

()

=

()()

Pro p .

m

p =· Ò0 302 0 298 0 196 0 204.,.,.,. .

mm

m

m

9.5. PRINCIPLE OF UNCERTAINTY INVARIANCE 389

Table 9.10. Probabilistic Approximation of a Given l-Measure (Example 9.12)

X Given Approximated

abcdm

¯

(A) m

¯

(A) m(A) Pro(A) m(A)

A:00000.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000

10000.302 0.722 0.302 0.302 0.302

01000.119 0.447 0.119 0.298 0.298

00100.039 0.196 0.039 0.196 0.196

00010.051 0.244 0.051 0.204 0.204

11000.600 0.900 0.179 0.600 0.000

10100.400 0.800 0.059 0.498 0.000

10010.430 0.819 0.077 0.506 0.000

01100.181 0.570 0.023 0.494 0.000

01010.200 0.600 0.030 0.502 0.000

00110.100 0.400 0.010 0.400 0.000

11100.756 0.949 0.035 0.796 0.000

11010.804 0.961 0.046 0.804 0.000

10110.553 0.881 0.015 0.702 0.000

01110.278 0.698 0.006 0.698 0.000

11111.000 1.000 0.009 1.000 0.000

9.5.2. Probability–Possibility Transformations

Let the n-tuples p =·p

1

, p

2

,...,p

n

Ò and r =·r

1

, r

2

,...,r

n

Ò denote, respectively,

a probability distribution and a possibility profile on a finite set X with n or

more elements. Assume that these tuples are ordered in the same way and do

not contain zero components. Hence,

(a) p

i

Π(0, 1] and r

i

Œ (0, 1] for all i Œ ⺞

n

.

(b) p

i

≥ p

i+1

and r

i

≥ r

i+1

for all i Œ ⺞

n-1

.

(c) (probabilistic normalization).

(d) r

1

= 1 (possibilistic normalization).

(e) If n <|X|, then p

i

= r

i

= 0 for all i = n + 1, n + 2,...,|X|.

Assume further that values r

i

correspond to values p

i

for all i Œ ⺞

n

by some

scale, at least ordinal.

Assuming that p and r are connected by a scale of some type means that

certain properties (such as ordering or proportionality of values) are pre-

served when p is transformed to r or vice versa. Transformations between

probabilities and possibilities are thus very different under different types

of scales. Let us examine these fundamental differences for the five most

common scale types: ratio, difference, interval, log-interval, and ordinal scales.

1. Ratio Scales. Ratio-scale transformations p Æ r have the form r

i

= ap

i

for all i Œ ⺞

n

, where a is a positive constant. From the possibilistic normaliza-

tion (d), we obtain 1 = ap

1

and, consequently,

for all i Œ ⺞

n

. For the inverse transformation, r Æ p, we have p

i

= r

i

/a. From

the probabilistic normalization (c), we get 1 = (r

1

+ r

2

+ ···+ r

n

)/a and,

consequently,

for all i Œ ⺞

n

.

These transformations are clearly too rigid to preserve any other property

than the property of ratio scales, r

i

/p

i

= a or p

i

/r

i

= 1/a, for all i Œ ⺞

n

. Hence,

the principle of uncertainty invariance cannot for formulated in terms of the

ratio scales. Since there is no obvious reason why the ratios should be pre-

served, the utility of ratio-scale transformations between probabilities and

possibilities is questionable.

p

r

rr r

i

i

n

=

+ +◊◊◊+

12

r

p

p

i

i

=

1

p

i

n

=

=

Â

1

1

390 9. METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES

2. Difference Scales. Difference-scale transformations use the form r

i

= p

i

+ b for all i Œ ⺞

n

, where b is a positive constant. From the normalization

requirements (d) and (c), we readily obtain

for all i Œ ⺞

n

, respectively. These transformations are as rigid as the ratio-scale

transformations and, consequently, their utility is severely limited for the same

reasons.

3. Interval Scales. Interval-scale transformations are of the form r

i

= ap

i

+

b for all i Œ ⺞

n

, where a and b are constant (a > 0). Determining the value of

b from the possibilistic normalization (d), we obtain

(9.9)

for all i Œ ⺞

n

, and determining its value from the probabilistic normalization,

we obtain

(9.10)

for all i Œ ⺞

n

, where

is the average value of possibility profile r. To determine a, we can now apply

the principle of uncertainty invariance by requiring that the amounts of uncer-

tainty associated with p and r be equal. While the uncertainty in p is uniquely

measured by the Shannon entropy S(p), there are, at least in principle, three

options for r: GH(r), GS(r), S

¯

(r). The most sensible choice seems to be GH,

which is supported at least by the following three arguments: (1) GH is a

natural generalization of the Hartley measure, which is the unique uncertainty

measure in classical possibility theory; (2) in possibilistic bodies of evidence,

nonspecificity (measured by GH) is more significant than conflict (measured

by GS) and it dominates the overall uncertainty, especially for large sets of

alternatives; and (3) the remaining option, S

¯

, is overly insensitive. It is thus

reasonable to express the requirement of uncertainty invariance by the

equation

(9.11)

SGHpr

()

=

()

.

a

n

r

ri

i

n

=

=

Â

1

1

p

ra

n

i

ir

=

-

+

a

1

rpp

ii

=- -1

1

a()

rpp

pr

rr r

n

ii

ii

n

=- -

()

=-

+ +◊◊◊+

1

1

23

,

9.5. PRINCIPLE OF UNCERTAINTY INVARIANCE 391