Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Tapestry

681

Tapestry

Tapestries are among the fi rst things people think of when they picture Eu-

rope in the Middle Ages. However, they were really an art form of the later

Middle Ages and were only found in churches and castles. The most famous

tapestry, the Bayeux Tapestry, is not even a tapestry. It is an embroidered

linen wall hanging. True tapestries were decorative cloth wall hangings; the

picture was woven into the fabric, not stitched onto it. They were made on

very large looms, with painstaking care, by trained professionals.

Tapestries before 1300 are scarce and primitive, perhaps produced in

home workshops or convents. Tapestry became a guild craft during the

12th century, and the 15th and 16th centuries were the peak of the tapestry

industry’s art. The workshops clustered in the cloth -producing regions of

Flanders and northern France. Paris and Arras led tapestry weaving in France,

and in Flanders, the most famous tapestry cities were Bruges, Ghent, Lille,

and Tournai. The trade spread into places like Italy only by the emigration

of Flanders-trained weavers.

Only the wealthiest patrons could afford tapestries. The price of a tap-

estry varied with the materials used (wool was the least expensive) and the

level of detail desired. When fi ner threads were denser, more detail was pos-

sible, but the weaving slowed, and the tapestry’s cost soared. On average,

a tapestry weaver did very well to produce 10 feet per year. The price of a

very large tapestry was astronomical. Less wealthy patrons had small tapes-

tries or mere imitations—fabric with painted pictures.

The church may have been the greatest customer for tapestries. A long

tradition going back into the early church of Roman times specifi ed that on

special feast days, churches had to hang decorative fabrics. Popes gave silk

and gold hangings to churches, and local donors gave money to be used

for hangings in their memory. Many of these altar cloths and banners were

embroidered, but as tapestry craftsmanship spread, large churches collected

woven hangings. Church offi cials such as wealthy canons, or royalty on the

church’s behalf, commissioned large tapestries to hang in the choir stalls,

completely covering the space. Some of these tapestries were very long, close

to 100 feet. They were usually about 6 feet tall, so they formed very long

strips of pictures.

Liturgical tapestries usually illustrated the lives of a church’s patron

saints, and they usually included text that explained the action. The scenes

of action were divided by decorative pillars or walls. As in other medieval art,

the costumes and buildings depicted in the saint’s story were contemporary;

Roman guards wore 15th-century hats and doublets, and every town had

a crenellated wall around it. The medieval love of the exotic brought uni-

corns, lions, and monkeys to the death of Saint Stephen or a newly invented

late medieval clock tower into the buildings of Rome.

Tapestry

682

Tapestry designs were busy. A picture for a tapestry had many human fi g-

ures, many animals, and wildfl owers scattered across the grass. Not all de-

signs were liturgical, of course. Secular tapestries showed hunting scenes

and gardens; men blew horns and tended dogs, while groups of ladies

walked, read, and sang in gardens. Some tapestries had ships, heraldic ani-

mals, kings, or castles. Unicorns were always popular.

The millefl eurs style was characteristic of 15th-century tapestries. They

displayed many small fl owers scattered on a solid background. The fl ow-

ers are always shown as whole fl owering plants, with as much variety as

possible. In the famous Unicorn Tapestry at the Cloisters of New York’s

Metropolitan Museum of Art, the white unicorn sits in a small enclosure,

surrounded by more than 80 different types of fl owers, most of which can

be identifi ed by naturalists: orchid, Chinese lantern, carnation, Madonna

lily, thistle, columbine, pansy, marigold, and many more. A millefl eurs tap-

estry typically had a central design—often an enclosure with an animal, but

sometimes a group of other fi gures. The background color was most often

green, to represent grass and make the tapestry appear to be a natural gar-

den, but some tapestries used other colors to good effect.

Making a Tapestry

The making of a tapestry began with sketches and proceeded to a full-

size cartoon. Sometimes the tapestry was fi rst painted onto a large piece of

cloth to see the full effect. Professional artists, not weavers, made these draw-

ings and cartoons. When the patron had approved the design, the cartoons

went to the weaving shop, where they became the shop’s property. Unless

the patron bought the cartoon or painted fabric test piece, the weaving

shop was free to make a copy and sell it. Sometimes the patron used the

painted fabric as a wall hanging while the tapestry was in production; the

less wealthy used nothing but painted fabric hangings.

The warp was a strong wool thread in a plain color. Weft threads were

usually fi ne wool and sometimes silk. Silk had a sheen that could be used for

a lightening effect. Gold and silver threads also were used for effect. Wool

dyes were simple, compared to artist’s painting tints. Using madder or brazil-

wood for red, weld for yellow, and woad or a type of indigo for blue, dyers

created the secondary and tertiary colors and many shades. Dyers added a

mordant, a chemical that fi xes the dye to the yarn; it was often a metal such

as aluminum or zinc. Even the most colorful medieval tapestries appear to

have no other substances but these few dyes and mordants.

Tapestry weavers worked on both upright and horizontal looms. The

vertical loom is called high warp, and the horizontal loom is low warp, but

the tapestries they produced were identical. The high warp technique came

fi rst. The weavers stood in front of a beam that wound up the fi nished fab-

Tapestry

683

ric as they worked. The warp was stretched tightly to an overhead beam that

unrolled the length of warp as the weavers moved upward. A simple draw-

string system, connected to a bar, lifted alternate threads to create a shed, a

space where the bobbin could be passed. On the low warp loom, the ar-

rangement was similar; a beam at the front rolled up the fabric as it was pro-

duced, and the warp was stretched and rolled around a back beam. With a

low warp loom, the drawstrings that raised or lowered alternate threads

were connected to overhead pulleys and foot pedals, leaving both hands

free to weave.

Up to six weavers, but on average three, worked side by side at these

large looms. On a low warp loom, each controlled a section of warp with a

set of foot pedals. The width of the tapestry was the desired height as it

hung in the room, and if a tapestry was not designed to be square, it was de-

signed to be longer against the wall than it was high. For this reason, the

weavers worked on the pattern sideways; the warp threads that stretched

in front of them would run horizontally when the fi nished tapestry was

mounted on a wall.

They worked with their fi ngers, pushing a bobbin of colored thread up

and down through the warp threads. Small details would use the width of

only a few warp threads, while large colored areas, such as blue sky, would

carry the bobbin across many warp threads before it came to another color

zone. Bobbins not in use hung or laid at rest on the fi nished fabric. At any

given stretch across the piece, anywhere from a few to a hundred different

bobbins could be in use. As they wove, the weavers used combs to pack the

weft to a tight, even density.

Sometimes, the artist’s cartoon was stretched under a horizontal loom so

the weavers could look down and see it. If they were working on a vertical

frame, the cartoon hung on a wall, but not immediately behind the vertical

loom. Weavers had to turn and look at the cartoon, then turn back to the

warp. They used charcoal or chalk to sketch the design onto their warp threads.

The design was worked facing away from the weavers, who saw only the

back of the tapestry picture. This way, they could secure threads in ways that

could not be seen from the front. On a high warp loom, the weavers could

walk to the back to see the front. On a low warp loom, they needed a mirror

on the fl oor to see the front as it developed. Weavers never saw the whole

picture until it was cut from the loom.

At points where colors joined, the weaver could wrap both colors around

a warp thread that formed the boundary, a technique called dovetailing.

Since two colors shared that thread, one to the left and one to the right, the

boundary was slightly blurred. Weavers could also interlock the colored

weft threads around each other as each color turned back; the join was in-

visible at the front. At points where the design required a crisp line between

colors, the weaver would leave a slit between them; one color turned back

Taverns and Inns

684

the way it came, not touching the other, which also turned back. Slits had

to be small because they weakened the fabric’s strength. The weaver then

stitched the slits closed on the back of the tapestry. The last step in fi nishing

the tapestry was to stitch on a protective linen backing.

Tapestry weaving was very dense; the weft threads were packed hard

against each other. Especially in late medieval tapestry technique, the pat-

terns were extremely detailed and used many shades of color. A man’s hair

was not a single brown; it was a fi ne pattern of dark and light browns that

created an illusion of hair strands with sun shining on them. Robes required

many colors to form the shadows and folds of cloth. Skies were not purely

blue but had shades of blue and white cloud. At the horizon, tiny houses

and castles were worked against the sky.

See also: Cloth, Embroidery, Painting.

Further Reading

Broudy, Eric. The Book of Looms. Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England,

1979.

Freeman, Margaret B. The Unicorn Tapestries. New York: Metropolitan Museum

of Art, 1983.

Quye, Anita, Kathryn Hallett, and Concha Herrero Carretero. “ Wroughte in Gold

and Silk”: Preserving the Art of Historic Tapestries. Edinburgh: National Mu-

seums Scotland, 2009.

Weigert, Laura. Weaving Sacred Stories: French Choir Tapestries and the Perfor-

mance of Clerical Identity. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004.

Woolley, Linda. Medieval Life and Leisure in the Devonshire Hunting Tapestries.

London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2002.

Taverns and Inns

Taverns were a natural outgrowth of the ale home-brewing industry. Many

women in the town and the country brewed ale in quantities greater than

their families could drink before it spoiled. The simplest kind of tavern was a

private house that permitted customers to sit at a table in the front room

and drink the ale they had purchased. The traditional English symbol for a

public house was a pole, broom, or branch posted above the door.

As cities grew, some taverns became businesses separate from home brew-

ing. They named themselves “The Cock” or “The Vine” and had colorful

pictorial signs. Taverns that did not brew their own ale or beer became tied

to certain brewers with whom they kept purchasing accounts, especially in

Germany and the Netherlands. Taverns in wine-growing regions sold only

wine, but since wine was widely imported, London customers at large tav-

erns could buy sweet Greek malmsey or any of 50 French or Italian wines.

Taverns and Inns

685

Some taverns sold food, although many did not. When a tavern did sell

food, the fare was likely to be simple and not likely to spoil, such as salted

fi sh. Tavern keepers could also buy bread from a nearby bakery. Many taverns

were prevented from cooking on the premises, since guild regulations did

not include cooking. They could buy salted beef, bacon, pies, or other food

from cookshops; customers could also buy from cookshops or street vendors

and carry the snacks in. Cookshops sold small meat pies, often in trays car-

ried by street criers. They also offered pieces of roast meat (hot off the spit

or griddle) and hard-boiled eggs. Street vendors made some things right on

the street, over a small charcoal fi re. One such treat was the wafer, something

like waffl es, pizelles, and the funnel cakes of modern carnivals. Some vendor

foods were not cooked, such as cheese and apples or pears sold from trays.

Taverns fl ourished because they fi lled a community need. Because hous-

ing was so cramped, it was almost impossible for many medieval men or

women to invite friends to their houses. Wealthier people had larger homes,

so taverns belonged to the poorer classes. Neighbors and students gathered

in taverns regularly to meet each other. Many business transactions among

the middle and lower classes were settled at taverns. In some places, taverns

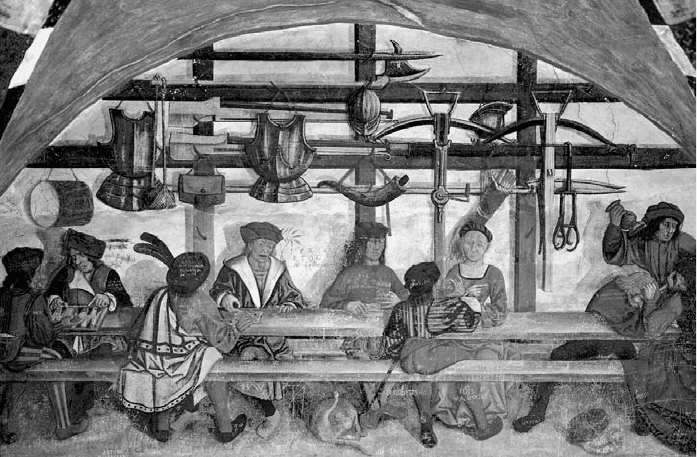

By the close of the Middle Ages, travel was fairly common, and inns had become

important hubs. In this Italian inn, the travelers appear to be storing their weapons on

wall and rafter hooks. A long table at an inn offered many places for strangers to meet

and mix, but at the same time, it mimicked feast tables where sitting in a certain place

indicated a man’s social importance. Some inns ordered round tables to keep guests from

arguing. (Castello di Issogne, Val d’Aosta, Italy/Giraudon/The Bridgeman Art Library)

Taverns and Inns

686

were also tax-collecting stations; in Poland, some taverns were managed by

law courts.

Because taverns were transient meeting places, they were frequented by

troublemakers. Fights broke out in taverns, sometimes spilling into the streets

and turning into riots. Students in university districts were infamous for

tavern fi ghts and riots. Playing games, with or without gambling, was very

common at tavern meetings; medieval people played dice, and cards came

into use by the 15th century. Public houses were good places to meet and re-

main anonymous, so prostitution was always close by a tavern, if not oper-

ating out of the tavern itself. Some tavern keepers were accused of hiring

out their servant girls as prostitutes.

Cities took an interest in regulating the tavern business. Paris imposed a

curfew on taverns to keep fi ghting and prostitution in check. London regu-

lations declared that tavern keepers had to permit customers to inspect their

barrels. Wine and ale sometimes soured or were served in dirty containers.

Even home-business taverns were inspected for fair prices. There were reg-

ulation quarts and gallons, and every alewife, even in small towns, had to

bring her containers in for inspection periodically. Even so, taverns remained

crowded, dirty places of very dubious reputation.

Taverns did not offer lodging. In the early Middle Ages, few people trav-

eled. Aristocrats stayed at friends’ castles and manors, and lodging for poor

people was very limited. In some places, private houses offered lodging for

a fee but either did not mark their buildings as inns or used a simple signal

like the branch that indicated a tavern. The lodgings in these early inns varied

greatly, but most travelers could expect nothing better than a cot or a shared

space in bed with other travelers or family members. Some monasteries of-

fered guest lodgings, especially for pilgrims.

The 12th century saw an increase in pilgrim traffi c, after the Crusades

established hostels to protect pilgrims. Roads improved during the 12th

and 13th centuries. The fi rst real inns were along international pilgrim

routes, but as more regional and local shrines developed, more inns devel-

oped. The medieval term for a place of lodging was more often a hostel or

hostelry. Some hostels rented horses, and others just provided a stable for a

traveler’s horse. A full-service, large hostelry on a pilgrim route required a

large house with a hall for communal dining, chambers and beds, a courtyard

with latrines, and a stable.

An innkeeper lived in the same house and literally shared his rooms, beds,

and supper with travelers. Most inns were run by a married couple with a

small staff of servants. Supper was a communal affair, as depicted in the Can-

terbury Tales. The host ate with the clients; he had a legal interest in remain-

ing with them as much as possible. An English law of 1285 made the hosts

of taverns and inns responsible for what their clients did. It was in the inn’s

interest to keep everyone calm and friendly, to see that everyone was in bed

Tools

687

at a good hour, and to watch for suspicious behavior. Robbery, especially of

horses, was common at inns.

When the guests went to bed, they were still in communal quarters. While

some inns had private rooms, many medieval inns expected guests to share

beds. A traveler could expect to sleep with at least one other person, and

some inns prided themselves on very large beds that could be packed with

whole groups. Some guests could even sleep crosswise along the feet. Since

discrimination on the basis of wealth and social standing was normal in the

Middle Ages, a higher-status traveler could expect the only private room,

while a poor man was lucky to have space at the foot of a crowded bed.

The character of the host made the inn’s reputation. The Host in the Can-

terbury Tales, Harry Bailly, was a respectable man who knew how to size up

the needs and social standing of each guest. He took a leading role in di-

recting conversation and preventing fi ghts. An inn was considered good if it

had no more fl eas than usual, provided decent food, and still had the same

number of horses stabled in the morning. In a bad inn, the food was dirty

or spoiled, the beds were obviously dirty, and the innkeeper worked with a

theft ring to make the better horses disappear.

See also: Beverages, Cities, Food, Games, Pilgrims.

Further Reading

Hanawalt, Barbara A. Of Good and Ill Repute: Gender and Social Control in Medi-

eval England . New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Henisch, Bridget. The Medieval Cook. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 2009.

Reeves, Compton. Pleasures and Pastimes in Medieval England. New York: Oxford

University Press, 1998.

Roux, Simone. Paris in the Middle Ages. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania

Press, 2009.

Thatch. See Houses

Tools

Basic hand tools have not changed much since antiquity. A few new tools

were invented during the Middle Ages, and all were improved and special-

ized for various crafts. European workmen liked to tinker with and improve

their traditional tools.

The development of tools followed the development of the blacksmith’s

art. Most farm tools were made of wood during the Carolingian era; only

cutting blades were iron, because it was still very expensive. Iron-edged

tools included spades, axes, scythes, and plowshares. Blacksmiths were gen-

erally located on estates, where they made weapons and horseshoes for the

Tools

688

knights. Making tools was a sideline. During the 12th century, there was

a growing demand for tools as population and cities grew. Blacksmiths set

up in towns and began focusing on civil uses of iron. In the later Middle

Ages, iron became more plentiful, and more common tools, such as rakes,

pitchforks, and shovels, could be metal.

Every profession had its specialized tools, and some tools, such as em-

broidery scissors, have left little evidence in the archeological or pictorial re-

cord. Scissors were in use, along with other specialized cutting tools like

surgeon’s instruments. Pictures of shoemakers and goldsmiths show some of

the specialized knives, scales, and chisels particular to each profession. The

greatest number of pictures through several centuries was devoted to the

tools of the building trade. Many Bibles and prayer books chose to illustrate

the story of how the Tower of Babel was built, and these pictures always

showed lively construction sites fi lled with contemporary workers. Because

of this, we have detailed knowledge of the tools used in construction.

Ditches, foundations, and all kinds of earth barricades and mounds were

dug with shovels and spades. This was unskilled labor and could be done

by peasants hired as day laborers. They used simple baskets and wheelbar-

rows to cart away the earth. Wheelbarrows shown in 13th-century pictures

are similar to modern ones; they have a platform with a slight basket shape,

a single wheel, two handles, and legs to rest the barrow on when stationary.

Another carrying device was the pannier, which consisted of two long bars

with a sheet of leather fastened between them. Two men carried the pan-

nier heaped with stones or earth. For the heaviest loads, they used carts with

two or even four wheels.

The signature building material of the Middle Ages was stone, although

relatively few buildings actually used stone. Castles and cathedrals aimed

at permanency and could afford the expense in materials, workmen, and

time. Masons were general contractors for working with stone, from archi-

tects to rough-hewing in quarries.

Masons in quarries mainly used heavy mallets and hammers with strong

chisels. The chisels were tempered by being reheated many times so that

they would be stronger than any material they came against, but, even so,

they had to be sharpened daily. Hammers could be pointed, a cross between

mallet and ax. There were also stone axes, used to smooth rough-cut stone.

Mallets and mauls beat against iron chisels and could have beechwood

heads. Punches were like smaller chisels with pyramidal ends and were used

to cut stone into fi ner shapes. For fi ner stone carving, masons used a variety

of chisels, punches, and hammers.

Masons used squares and plumb bobs to make sure that lines were

straight and edges were truly vertical. The plumb bob was a piece of lead

shaped with a point and hung from a string; it always pointed to the earth

and created a perfectly vertical line. Masons used compasses to draw true

Tools

689

circles on the stone and measuring staffs to get the correct rough sizes.

They often sat on three-legged stools, measuring stone and fi tting it with

their wooden templates to get the right shapes.

Next to stone, brick was a favored material for castles, churches, guild-

halls, and town buildings. Bricklayers relied even more heavily on the plumb

bob to keep their wall straight; they also kept a straightedge and a level. A

medieval level was a fl at board with a wooden triangle built over it. A plumb

bob hung from the apex of the triangle. When it pointed straight down at

the mark, the level was sitting perfectly horizontal; if the plumb bob pointed

to either side of the mark, the wall was not level. The bricklayers’ other tools

were for applying mortar between bricks. They had a mortar-mixing bin and

a pick for mixing the mortar, a shovel, and a smaller bin for carrying the

amount needed to the wall. Bricklayers used a trowel that was identical to

modern mortar trowels and a hammer for knocking the bricks into better

alignment. For carrying bricks, mortar, or stones, a carpenter’s helper used

a hod. The hod was a shallow wooden dish with handles; because it was car-

ried on the shoulder, it was often fi lled while placed on a tall stool so that

the carrier could easily stoop under to lift it up.

Although castles and cathedrals were usually built of stone, most houses

and other buildings in England and France were made of timber. Carpen-

try was skilled work and was carried out with hand tools similar to those in

modern times, before the use of electric tools. One notable omission is the

screwdriver; screws were not yet in use.

Carpenters used at least four different axes, beginning with the basic ax

for felling trees and a hatchet for smaller cutting. Broad axes were slightly

curved and set their blades perpendicular to the handle, like hoes; they were

used for shaping trees into square beams. Roofi ng axes were similar but

smaller and were used to cut gutters into roof beams and do other tasks that

required gouging out a hollow. The smaller adze resembled these but was

used to cut mortices into beams.

Drills were also called augers or bores. They were operated with a long

cross bar at the top, so the carpenter could turn the drill bit with two hands.

A cranked drill brace was not invented until the 15th century.

Blacksmiths made saws by cutting teeth into a plate of hot metal. There

were handsaws, chiefl y with thin blades held in tension in a frame, with a

torsion rope at the top to keep the blade taut. These came in small or large

versions for two men to use. Carpenters often used very long two-man saws

with handles on both sides, especially when cutting a log into boards. Saw-

horse trestles were part of their usual sawing kit.

Carpenters used a few more miscellaneous tools. Planes smoothed the

square beams after they had been rough shaped by broad axes. There were

fi les, made by striking a stick of iron with a sharp hammer to create ridges.

Mallets and other hammers could be made of all wood or could have iron