Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Sieges

670

arm was lashed down, the men got out of the wheels, and the counter-

weight could be released.

Rocks are the best-known catapult payload, and they were the most

commonly used. A machine could deliver a series of rocks to the same spot

on a wall if the rocks were the same weight and the machine had not been

moved. This pounded the wall over and over, increasingly weakening it.

Iron shot was even better than stone shot, but it was more expensive.

As a siege went on, trebuchets were loaded with new payloads that were

intended to frighten or harm the people inside. The trebuchet was now

aimed to fl ing over the wall, not at it. Most often, armies threw dead ani-

mals or even dead human body parts. Severed heads were a common pay-

load. Corpses spread disease, a deadlier attack than any rock. An assault

with corpses was also a psychological terror weapon, especially if the heads

or other body parts belonged to the targets. Trebuchets could also fl ing

manure.

A shrapnel effect came from “beehives”—clay pots packed with rocks.

They burst open on contact, and the rocks fl ew into the town to smash win-

dows and injure people. Armies also threw incendiary mixes, such as hot tar

and quicklime. Incendiary mixes were often called naphtha; there are a few

existing recipes. Quicklime was the key ingredient, because water causes

combustion on contact. Other ingredients were fl ammable substances: pine

pitch, tar, oil, animal fat, and dung.

Greek fi re was the most famous incendiary compound of the time. The

name “Greek fi re” caught on because it was invented in Constantinople,

after they had lost territory to the invading Muslims. Byzantine soldiers

used catapults to fl ing pots of Greek fi re at besieging Muslim armies. It

caught fi re on contact, and even water did not put it out. They could pump

it at attacking ships and burn up whole fl eets; in this way, they saved Con-

stantinople in the seventh century when other cities were conquered by the

invading Arabs. The secret composition of Greek fi re was carefully guarded

for a long time, but eventually fi rst Muslims and then Christian Europeans

learned how to make it. It became a component of trebuchet attacks during

sieges. However, there is no surviving account of what was in Greek fi re.

Many scholars speculate that it must have contained quicklime or saltpeter,

and others believe it had to use petroleum as a main ingredient. The use of

petroleum in some form seems very likely, since Greek fi re was described as

a liquid that burned even on top of water.

After the introduction of gunpowder, cannons became the main siege-

breaking weapon. The largest cannons, called bombards, required large

trains of horses and oxen to move their parts and heaps of stone shot. They

had to be moved off their wagons with large cranes, and they were fi red

either from heavy wooden frames or from trenches dug into the ground.

The idea was not to fi re the stones or iron balls into the fortress, but to fi re

them straight at the defensive walls. A bombard that was placed lower to

Spices and Sugar

671

the ground could aim right at the ground level. It was most effective when

it was close to the wall, its operators defended with wooden walls.

See also: Armor, Castles, Gunpowder, Weapons.

Further Reading

Bennett, Matthew. Fighting Techniques of the Medieval World: Equipment, Combat

Skills, and Tactics . New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2005.

Carey, Brian Todd. Warfare in the Medieval World. Barnesly, UK: Sword and Pen,

2006.

Donnelly, Mark P., and Daniel Diehl. Siege: Castles at War. Dallas: Taylor Publish-

ing, 1998

Keen, Maurice. Medieval Warfare: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

1999.

Nossov, Konstantin. Ancient and Medieval Siege Weapons. Guilford, CT: Lyons

Press, 2005.

Partington, J. R. A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins University Press, 1999.

Payne-Gallwey, Ralph. The Book of the Crossbow: With an Additional Section on Cat-

apults and Other Siege Engines. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2009.

Rihll, Tracey. The Catapult: A History. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2010.

Wiggins, Kenneth. Siege Mines and Underground Warfare. Princes Risborough,

UK: Shire Publications, 2003.

Silk. See Cloth

Silver. See Gold and Silver

Slaves. See Servants and Slaves

Spices and Sugar

Medieval cooks considered anything used for fl avor to be a spice. Their

spices included the ones we are familiar with: cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger,

cloves, and pepper. They also included what we call herbs: thyme, sage, mint,

and parsley. But medieval spices included a range of ingredients that we

would not think of, such as dates, fi gs, almonds, and even grape juice. Sugar

was a spice. Anything that could change the fl avor of a meat dish was a spice,

and medieval cooks used all these ingredients in all dishes on the table.

The use of spices was often a matter of conspicuous display of wealth. Im-

ported spices were in the top rank, because they were the most expensive.

Imported sugar may have been the most expensive of all. Saffron, a spice

native to Europe, was also extremely expensive, so it too was favored by

cooks for the aristocracy. Herbs native to Europe were considerably down

Spices and Sugar

672

the scale of fashion and did not fi gure much in the most luxurious recipes.

Cooks knew that their diners wanted expense and display.

The spices imported from the Far East were pepper, cloves, nutmeg,

mace, cinnamon, cardamom, and ginger. These had been imported since

Roman times, shipped to Middle Eastern ports and then into the Mediter-

ranean Sea, but the supply dwindled to an expensive trickle during the years

of barbarian invasions. After Muslim Arabs conquered most of the Medi-

terranean, shipping and travel became more dangerous, and spices were

scarcer and more expensive. Only the richest could afford the few spices

that still entered Europe. But in 1099, the First Crusade set up a king-

dom in Palestine and its surrounding fortress cities, such as Antioch. For

the next 200 years, knights, masons, merchants, and other workers fl owed

back and forth to support this kingdom. Trade in spices soared. Venice,

Genoa, and other maritime cities obtained exclusive trade contracts for cer-

tain routes and places, while those places became wealthy by charging fees.

Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the main hubs of the spice trade.

The most popular imported spice of the Middle Ages was pepper, and

Europe was never entirely without pepper even during the years of most

privation. Pepper’s use was restricted to the aristocracy, though. It took a

greater supply and a lowered price for pepper and other spices to become

part of commoners’ lives. When the spice trade was reestablished follow-

ing the Crusades, spices became more common and were available to some

well-to-do merchants and craftsmen. In the later Middle Ages, after 1350,

as pepper became more available to the common man, it lost fashion among

the rich. Fewer recipes used pepper. By the close of the Middle Ages, pep-

per was viewed as the spice of the poor.

Medieval recipes were generously spiced. Sauces for meat included not

only salt and pepper, but also ginger, cinnamon, cloves, mace, cardamom,

and saffron, and often all at once. The wealthy, whose households kept

records still in existence today, purchased spices in staggering quantities.

Their cooks used upward of a pound of assorted spices a day to make their

stockpots of stews and sauces for the castle’s household. While some meat

and fi sh were eaten fresh, much of it had been salted, and this saltiness was

probably the driving force behind recipes that chopped meat fi ne, mixed

it with other ingredients, and drowned its taste in spices. Fresh meat, too,

such as venison or pork, was stewed or dipped into sauces seasoned with

cinnamon and ginger.

Many history books say spices were used to cover the taste of spoiled

meat or fi sh, but this does not hold up in a closer examination. Medieval

cooks and diners were aware that eating spoiled meat made people sick,

although their ideas of the mechanisms of food spoiling seem quaint and

were too heavily focused on the smells and bad air. Spices were probably

used as preservatives, and spoiled meat could be a problem, but merchants

Spices and Sugar

673

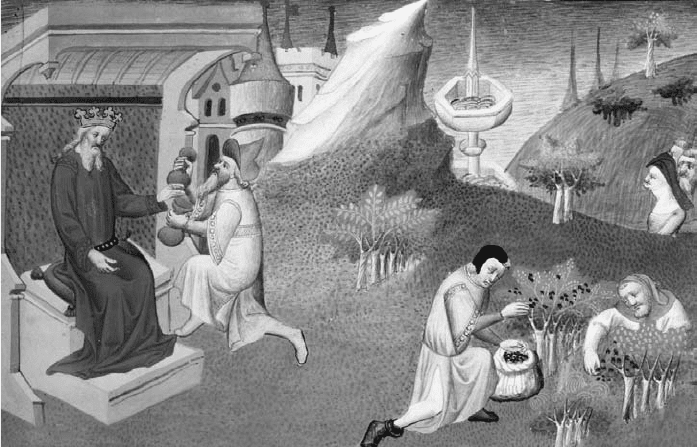

A 15th-century painter imagined the pepper harvest in the exotic, distant, unknown East

Indies. To the right, natives were hard at work picking pepper corns from bushes. To the

left, a merchant offered the results to a European king. Trade in pepper and other Indian

spices drove Europeans to explore the oceans, each trying to fi nd a way to corner this

lucrative market. (Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris/The Bridgeman Art Library)

who sold spoiled meat were subject to harsh punishment, such as time in

the public stocks.

A wide variety of herbs and spices were native to Europe. Some were

very common and were used only by the poor, who might gather them or

buy them for pennies at the market. Mustard grew wild all over Europe; the

yellow condiment we call mustard today began as a medieval sauce made

from vinegar, honey, and mustard seed. Sage, basil, fennel, mint, parsley,

rosemary, cumin, coriander, and thyme grew wild in various regions. Crab

apples, too, were gathered for their sour fl avor. Garlic, chives, and onions

were the most common seasoning for the poor.

Saffron is made from the dust on the stamens of crocus fl owers. These

fl owers, imported from Persia, were grown all over Europe, but it took

hundreds of crocus stamens to make any amount of saffron. The sheer time

and work required to make an ounce of saffron made it one of the most

expensive spices, and therefore it was much valued for its bright color and

distinctive taste. Other fl owers had scents valued as fl avoring in confections:

roses, violets, and the fl owers of the elderberry bush and hawthorn trees.

Spices also formed the basis of many medicines. Physicians believed that

the four humors of the body—hot, cold, wet, and dry—must be kept in

balance. They believed that disease was an imbalance of these humors and

Spices and Sugar

674

that fever was the body’s attempt to rebalance a system that had dropped

toward being too cold and wet. The remedy was to ingest or apply some-

thing that was hot and dry. Spices like cinnamon and pepper were con-

sidered the hottest, driest substances, so they formed the basis of many

medicines and poultices. Ginger was hot and wet, a rare combination, and

a much-valued medicine for some diseases. Spices had the additional value

of being expensive, so only the rich could have such medicine.

Sugar entered medieval Europe as an expensive import from the Middle

East, although sugar cane had originally come from the Far East. Around

the year 1000, the Arab empire set up a sugar refi nery on the island of

Crete, which they called Qandi, meaning “crystallized sugar.” The English

word candy clearly comes from this Arabic word.

Crusaders withdrawing from Palestine in 1291 established a kingdom in

Cyprus and grew sugar there. The republic of Venice shipped sugar from

Cyprus to the rest of Europe; so did Genoa and the Hanseatic League. As

the distance from sugar producers grew, the price went up, because each

port it passed through imposed a toll or tax. The price of a loaf of sugar in

France or England was as much as its weight in silver.

The most common “candy” was candied whole spice, whether ginger,

nutmeg, or even pine nuts. Nougat, a confection of sugar and nuts, was in-

vented during the Middle Ages, probably in Spanish-Arab Andalusia. The

Arabs also invented caramel, kurat al milh, meaning “ball of sweet salt.”

Caramel was sometimes used to remove unwanted hair, the way we now

use wax. Ordinary medieval Europeans never saw or imagined these sweets;

their availability to the public would only come with the New World trade

in the next era.

Very few sweet desserts were part of the medieval European table. Al-

most all the cookies, cakes, and pies that we consider part of traditional

European cuisine were developed later. However, toward the end of the

Middle Ages, some cooks developed gingerbread. The earliest gingerbread

was millet gruel boiled with honey, with spices added. Poured into a mold,

it cooled and solidifi ed, then was baked. The fi rst true gingerbread came

from Reims in the 1420s, when a bakery invented a spice bread made from

rye fl our, dark buckwheat honey, and spices. Sometimes this bread was cut

into cubes and dipped into the spicy meat sauces at dinner.

See also: Food, Gardens, Medicine.

Further Reading

Adamson, Melitta Weiss. Food in Medieval Times. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press,

2004.

Freedman, Paul. Food: The History of Taste. Berkeley: University of California Press,

2007.

Stone and Masons

675

Freedman, Paul. Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination. New Haven,

CT: Yale University Press, 2009.

Tannahill, Reay. Food in History. New York: Three Rivers Press, 1988.

Turner, Jack. Spices: The History of a Temptation. New York: Knopf, 2004.

Stained Glass. See Glass

Stone and Masons

Stone was the high-tech building material of the Middle Ages. Wooden

buildings predominated in the early centuries because stone was so expen-

sive. Only palaces and churches were stone, at fi rst. By the 12th century,

castles had to be stone, as did city walls. By the end of the Middle Ages,

many bridges, some roads, and many houses were stone. Estimates sug-

gest that more stone was quarried in medieval France than in ancient Egypt

to build the pyramids.

Stone was used for other purposes than just building blocks. Italian mar-

ble was carved into monuments; marblers were very specialized stonecut-

ters. Slate broke into fl at slabs to make roof tiles. Limestone and chalk were

burned to produce quicklime, an element of mortar. Large limestone kilns

used acres of forest as fuel; they were among the fi rst to convert to coal

when it was discovered in the 13th century.

Stone building was planned and overseen by master masons, the archi-

tects of the Middle Ages. They signed a contract with the owner and acted

as general contractor to hire other skilled workers to carry it out, under the

stipulated budget. They drafted the plans and drawings, inspected build-

ings, and supervised stonecutting and actual building. Other masons were

rough masons who hacked out rough shapes at the quarry, stonecutters

who made precision blocks, and freemasons who could carve anything in

stone, including window tracery and other sculpture.

Some stone quarries were owned by the king or by monasteries, others

by private owners. France was the region most heavily quarried for build-

ing stone; much of it came from Caen, in Normandy. It was fantastically

expensive to have stone moved far, so builders usually searched for places

to quarry it locally. When only Caen limestone would do, the stone had to

be moved by boat. In a few cases, it was best to dig a canal just to transport

the stone to the building site.

Medieval quarries tunneled into the hillside, creating long galleries that ran

parallel to each other or branched off in mazes. The tunnels were propped

up with rock pillars, or the stonecutters left natural pillars. Paris has tunnels

where the stone quarries dug down under the city. There are more kilome-

ters of medieval quarry tunneling than of the modern Paris subway.

Stone and Masons

676

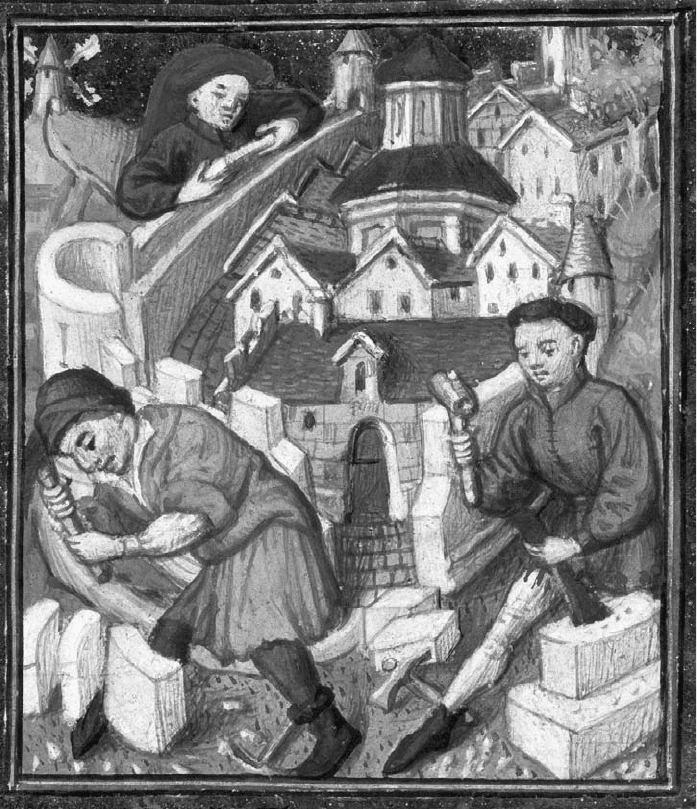

A 15th-century artist represented the importance of stone by showing masons

towering over their building project. Each is working with typical masons’ tools

on a different phase of cutting, shaping, and placing blocks. In the far upper

left corner, there is a windmill against the horizon. (The British Library/

StockphotoPro)

Rough masons used stonecutting tools in the quarry, such as picks, mal-

lets, and chisels. These had to be sharpened frequently. When possible,

stones were cut to order at the quarry. Master masons sent written orders

with sticks marked to the size of the stones to be cut or canvas cut into pat-

terns. In the quarry or in their lodge workshops, the rough masons cut the

Stone and Masons

677

stones of a building to precise patterns. Sometimes stone pieces interlocked

to form a weight-bearing pillar. Many stones had carved patterns; dressed

stone like this was called ashlar. The stones were marked to show where

they fi t into the fi nished wall.

After 1300, architectural drawings were more common, and many have

survived into the present. The earliest are on parchment, later ones on

paper. Some were very large, drawn on several parchments stitched to-

gether. Some show several elevations superimposed on each other, in two

dimensions. A tower that grew narrower at the top could be drawn as if

it were a series of walls inside each other, showing their relative size and

shape. Much of the mason’s art and training was in understanding these

drawing conventions and knowing how to interpret them. By the master

mason’s directions, the patterns were drawn full-size on a tracing fl oor that

had a fi ne plaster coating that was easy to mark. Carpenters used the shapes

on the drawing fl oor to make wooden forms that the stonecutters used to

shape the stone pieces into replicas of the shapes laid out by the master

mason. Accurate replicas were especially important in assembling Gothic

arches and tracery.

Foundations were laid out with pegs and strings, and until the 11th cen-

tury, walls were not always perfectly straight or perpendicular, but from

the 12th century on, they were very geometrical. Master masons were very

aware of the importance of good foundations and shored up soft ground

with driven piles.

To build a wall, masons used only the classic trowel, identical to those

used by bricklayers today, and a simple level. The level consisted of a fl at

piece of wood with a triangle built onto its surface; from the apex of the

triangle hung a short line with a weight. When the base was on a perfectly

level surface, the weight hung down to point at a mark directly under it.

Any deviation from this level caused the weight to hang to the right or left

of this central mark.

Builders used scaffolding similar to the modern kind, consisting of strong

but temporary poles and shelving. The shelves in a medieval scaffold were

made of wattle (woven branches) rather than solid boards, and the frame

was tied together with rope. Builders often built round towers by insert-

ing poles into holes built into the wall as they went and raising a spiraling

walkway as they built. Ladders often connected levels, but they also made

walkways by weaving fl exible splints into the ladders’ spaces.

See also: Cathedrals, Tools.

Further Reading

Coldstream, Nicola. Masons and Sculptors. Toronto: University of Toronto Press,

1991.

Stone and Masons

678

Gimpel, Jean. The Medieval Machine: The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages.

New York: Penguin, 1976.

Harvey, John. Mediaeval Craftsmen. New York: Drake Publishers, 1975.

Hislop, Malcolm. Medieval Masons. Botley, UK: Shire Archaeology, 2009.

Sugar. See Spices and Sugar

T