Johnston R.A. All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Salt

620

gradually form and fall to the bottom of shallow water, where they can be

raked up. During the Middle Ages, salt was both mined and harvested from

salty brine.

In Europe, the premedieval Celts mined and sold large quantities of salt

for several centuries. Their Roman conquerors also made large amounts of

salt by boiling seawater in pottery until a solid block of salt was formed

(they smashed the pot to get the salt) and by building shallow ponds along

the Mediterranean to let the sun and wind evaporate seawater until salt

crystals formed. At the start of the Middle Ages, people in Europe contin-

ued to use the many saltworks the Romans had established along the shores

of the Mediterranean and Adriatic seas.

Venice became rich as a leading salt exporter, thanks to an important in-

novation. Instead of using a single pond, salt makers constructed a series of

shallow ponds. The fi rst was a large open tank into which seawater fl owed.

The tank had sluices that kept additional seawater from entering the pond

while the sun and wind did the fi rst part of the evaporation. When the brine

reached a certain degree of salinity, pumps sent it on into a second pond for

further evaporation, and the sluices were opened to allow more seawater

into the fi rst pond. When water in the second pond reached a higher level

of salinity, the water went to a third pond, and the process was repeated,

and so on, until coarse salt crystals formed and could be raked up and dried.

Over the course of a year, this method produced a large quantity of salt

while requiring very little manpower. The salt produced by this long, slow

evaporation process was a coarse salt, very suitable for salting fi sh, which

was an important local industry.

The amount of salt a city could make and sell was limited only by the

space it had available. The Venetian method spread through the Mediter-

ranean during the eighth and ninth centuries. The best salt came from the

Bay of Biscay, where the Loire River empties into the ocean. It was called

Bay Salt, and it commanded a high price in other parts of Europe.

The shallow pond method worked well in a warm, sunny climate but not

in cooler and cloudier northern areas. In early medieval times, the English

made salt by boiling brine in shallow lead pans laid over a fi re—known as

the open pan process. The temperature of the brine and the rate of evapo-

ration could be controlled to produce fi ner or coarser salt for different uses.

Salt makers also used the pot process, pouring brine into ceramic or metal

pots hung over a fi re. A saltwork was called a wich house, a term that per-

sists in English place names. The brine came from lagoons or from the sea

itself.

The English also used sand from the seashore. Waves washed over the

beach, depositing salt in the sand. In a medieval technique called sleeching,

sand was air-dried and put into a pit (a kinch). Water (either sea or fresh)

was poured over it until brine fl owed out. The process was repeated until

Salt

621

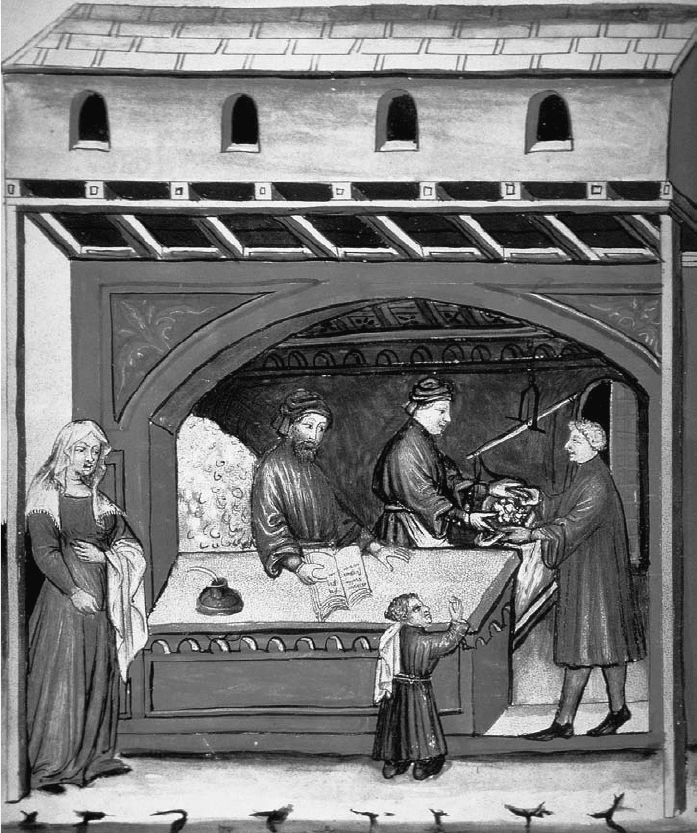

Salt was one of the few necessities of life that was almost always produced some distance

away; even common people had to buy salt at times. A salt merchant sold it by weight;

he probably measured it into a container that the customer brought from home. The

cost per pound was greater for cleaner, purer kinds of salt. (Osterreichische

Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Austria/Alinari/ The Bridgeman Art Library)

the brine was salty enough that an egg would fl oat in it. Then it could be

used as brine or dried for salt.

Brine springs and brine wells were another source of salt. Springs fl owed

in areas that had rock salt or in underground streams. To access the brine,

brine wells were equipped with machinery to haul bucketfuls up to the

Schools

622

surface. Men (often prisoners) walked treadmill-fashion on a giant slatted

wheel, which turned a shaft that wrapped ropes around itself, lifting buck-

ets of brine to the surface. The brine was boiled to make salt.

Rock salt underlies much of central Europe. The ancient Celts dug long

sloping tunnels into the mountain, used pickaxes to break up the salt, and

hauled it to the surface in leather bags. In the late 700s, rock salt mining

started again under the leadership of the Catholic Church. In the mid-13th

century, removing salt from a mine was made easier when water was piped

into the dug-out rock salt; the water quickly became brine and was piped

out of the mountain to a village, where it was boiled down. Income from

the salt helped support the church and many monasteries that were built

over brine areas. Salt was shipped via riverboats to other parts of Europe.

Southern Poland has deep deposits of rock salt. In the middle of the

13th century, miners began to dig out the rock salt that had hardened at

ancient brine springs. The fi rst miners were prisoners of war who were liter-

ally worked to death. In the 14th century, free men began to do the min-

ing. The mines became deep enough that the salt was hauled to the surface

by a huge pulley system worked by teams of eight horses.

Salt crystallizes in various sizes, depending mostly on the rapidity of the

evaporation process: the faster the evaporation, the smaller the crystals. The

fi nest salt is called fl eur de sel, a light salt that was skimmed off the water’s

surface during evaporation. The next fi nest crystals are salt for dairy use

(making butter and cheese); then come common salt, a coarser salt for cur-

ing ham, and the coarsest grades for salting fi sh, one of the most important

uses for salt. Coarser salt usually had minerals and dirt mixed into it.

See also: Fish and Fishing, Food.

Further Reading

Fielding, Andrew, and Annelise Fielding. The Salt Industry. Princes Risborough,

UK: Shire Books, 2006.

Kurlansky, Mark. Salt: A World History. New York: Penguin Books, 2002.

Schools

While most medieval people did not learn to read, many did—more as the

centuries passed. By the end of the Middle Ages, literacy was common,

though not yet universal. England’s literacy rate may have been higher

from the start, since reading and scholarship were prized by some Anglo-

Saxon kings, most notably King Alfred. Parents who could read were able

to teach children, and many parishes had priests who could read and were

willing to teach a few motivated pupils.

Schools

623

The children of country serfs met several obstacles to attending school.

In the countryside, it was harder to fi nd a teacher, let alone a school. If they

did, they needed the permission of their feudal lords to learn to read; the

feudal lord could even be the local abbot, if a monastery owned the land.

Whether the lord was a knight or a clergyman, he often charged the peas-

ant family a fee to let the boy go to school. It may be that this fee purchased

the boy’s freedom, allowing him to go to town not only to study, but also

to stay there and fi nd work.

Large towns had grammar schools for boys. In England, they were more

common after about 1200. At fi rst, most schools, whether run by a ca-

thedral, monastery, or private master, charged fees. There were both day

schools and boarding schools; in towns with day schools, some students

who came from a distance boarded with families. These schools primarily

taught Latin to prepare boys for careers in the church or as clerks. They

varied in size; most schools were restricted in size by their charter, either

to maintain quality of education or to protect the competition. A grammar

school held in a learned man’s home usually had no more than 6 pupils, but

large town schools could easily have 50 or more.

The Lateran Council of 1215 mandated that bishops must maintain free

schools for training future priests. After this, all cathedrals had schools at-

tached, often coordinated with their need for a boys’ choir. The cathedral

school of Notre Dame in Paris became one of the leading schools of music

where innovations were tested. Cathedral schools treated their pupils as

This picture decorated the cover of a

13th-century Latin book. It shows a

small monastery school of the time.

The teacher is seated on a stool, with a

stand to hold his book. The students sit

on the fl oor. Some have books, while

others must gather around to look on a

shared copy. If the students could read

along after the teacher, memorizing

what was on the page, the teacher

believed that they could read it. The

mechanics of decoding letters and

sounds were not of interest in the

Middle Ages. (Erich Lessing/Art

Resource, NY)

Schools

624

though they were part of the monastic community; the boys were pres-

ent at many church services, often singing, and they lived on the monastic

schedule. Bishops usually required their pupils to be tonsured like monks,

with their hair cut very short and a bald patch shaved on top. The students

did not have to take monastic vows, but they were counted as minor clergy

and often did become monks.

During the 14th century, some wealthy patrons endowed secular schools

that did not charge tuition. A secular school still ran according to reli-

gious methods, but it was not formally under the oversight of the bishop.

In England, Winchester College was endowed by a wealthy secular canon,

William of Wykeham, who later became bishop, but the school was not a

cathedral school. It was founded as a school, rather than as a charity or choir

of the cathedral. King Henry IV founded Battlefi eld School in 1409 at the

town of Shrewsbury, near where he had won a victory over a rebellious earl.

This small college was typical of privately endowed secular schools. It sup-

ported a teaching staff of only six, and it included an almshouse to care for

the poor, probably including its own poor students.

Next, town governments through Europe began endowing schools, es-

pecially in the Netherlands and Germany. Some of these secular schools

were entirely tuition free, funded by tax money. By the 15th century, large

cities like Paris had as many as 50 small schools, mostly for boys, but some

were for girls. Towns in Italy were organized as self-governing communes,

and, by the 14th century, the town governments ran more schools than the

churches did. While most schools remained private and charged fees, some

were directly supported by taxes. Higher-level schools were geared for the

needs of the Italian commercial empires, emphasizing accounting and doc-

ument writing.

The word college could mean either a preparatory school before univer-

sity or a division within a university. A medieval English college was often a

school for boys between the ages of 10 and 17. Students from all different

social ranks met at the school to learn, but the school honored their ranks

even as children. The sons of noblemen ate at a higher table than the sons

of tradesmen, and the poorest charity students served at table and ate with

the servants. It is likely that the difference in rank did not greatly bother

the students; the poor boys were used to hard work, and their status was

a kind of work-study program. In some schools, poor students who re-

ceived full scholarships to study without working had a high status because

it marked them as particularly intelligent.

Colleges that boarded a large number of students had to maintain a

large staff. Staff positions were the warden and the headmaster at the top,

with a team of instructors often known as fellows in medieval England

and an usher, whose job it was to mind the door to catch latecomers and

to instruct the youngest students. The college also needed support staff,

Schools

625

beginning with a steward and the warden’s clerk and descending through

the barber, cook, brewer, baker, laundress, valet, and servant boy. The serv-

ing staff was, of course, supplemented by the poor students who worked for

their tuition. They sang in the choir, served at table, and served the wealth-

ier students in their rooms, and they were not fed as well.

Some students at colleges did not continue to a university; as many as

half went into trades. Apprenticeships also seem to have included a fair

amount of general business education, such as how to write letters and con-

tracts and how to keep accounts. Some apprenticeship contracts stipulated

that the master would send the boy to school for a year or two as part of his

training. This was seen in trades that required some knowledge of reading

and arithmetic.

The age that most people considered ready for school was seven years

old. Before that, boys were considered babies and not fully male. For those

who were not taught at home, the school day began early, at dawn. Like

other medieval workers, teachers had to make use of daylight to save money

on lighting. Students were not expected to have breakfasted before they ar-

rived; in some schools, there was a meal break in the morning after the boys

had studied for a few hours. Boarding schools served a noon meal, while

schools in towns allowed the pupils to go home at noon. The boys returned

to school by about two in the afternoon, and the school day continued

until about six in the evening . The day was not devoted only to silent read-

ing or class recitations. Teachers also led the boys in prayers, in some cases

prayers for the souls of the men who had endowed the school or its indi-

vidual scholarships in exchange for these prayers.

School facilities were simple; they were not always buildings devoted to

the purpose. Sometimes they were rented from a guild, church, or trades-

man. At the beginning level, they did not use chairs and desks. Students

sat on the fl oor and learned their letters from wooden tablets with handles

that resembled ping-pong paddles. Some illustrations show small children

standing in front of either their father or their teacher, holding the alpha-

bet tablet so the instructor could look over their shoulders and point to

the letters as they read. Basic writing at this instructional level was often on

wooden tablets or slates that could be rubbed down and reused.

Early reading began with the alphabet and syllables and proceeded di-

rectly to the most important text, the prayer book. These prayers were in

Latin, and they were merely memorized by the pupils. Those who could

continue education beyond this level turned next to the psalter, often learn-

ing to sing as well as read. In England, the fi rst stage of real schooling

was called “music school.” Some young pupils never learned to understand

what they were singing but could sing in the church choir. Learning to read

in English may have been a lesser activity, a side benefi t of learning to read

Latin syllables.

Schools

626

The next step was to learn Latin by memorizing words, and then mem-

orizing the ways words could combine. This was “grammar school,” and

most grammar schools required students to prove basic reading skills for

entrance. Grammar schools were more likely to have dedicated classrooms;

some were boarding schools with dormitories. Cathedral schools were

usually boarding schools. The classrooms that grammar schools used were

simple, with benches along the sides, an open area in the center, and a

head desk for the teacher. Some had writing desks, but most required stu-

dents to rest books and writing materials on their laps. Most schools had

outdoor privies as latrines, but some expected students to use a nearby

riverbank.

Students at a grammar school needed to have some basic equipment be-

sides suitable clothing. They had their own pens, pen sheaths, penknives,

and inkhorns. They had to buy paper notebooks, and, at higher levels of

instruction, they also bought or rented a few hand-copied books. Their

school fees also contributed to purchasing fi rewood, hay for the fl oors, and

candles. Some schools required the students to bring a supply of beeswax

candles.

Learning heavily emphasized memorization, so a student who had mem-

orized a prayer was said to “read” it. Students memorized many things,

including poems, speeches, and psalms. Older students who aimed at uni-

versity study or clerical work learned to write at dictation; the teacher read

out loud, and the students copied. From the 15th century, we still have

paper notebooks students made as they learned Latin. They copied Latin

texts, did translations between Latin and English, and composed narratives

in Latin. Teachers seem to have used some riddles and rhymes, as well as

texts about everyday life, to teach Latin vocabulary and keep the work in-

teresting. Some of the extant notebooks suggest the teachers included vo-

cabulary the boys were interested in learning, including insults.

Mid-level students studied Latin intensively and often “parsed” words.

This meant that the teacher pointed out a word in a Latin text, and the

student had to state its part of speech and everything else that could be

known about the word’s form and use. Upper-level students were ex-

pected to speak nothing but Latin in the classroom, since at the univer-

sity, all classes would be conducted in Latin. A mark of having mastered

Latin was the ability not only to read and speak it but to write verses in

Latin.

The liberal arts, as defi ned in the Middle Ages, were grammar, dialec-

tic, and rhetoric, and after these, the higher arts of arithmetic, geometry,

music, and astronomy. While grammar schools often taught basic arith-

metic, they were mostly expected to teach only the fi rst three arts. An upper-

level student at a large grammar school could expect to begin to learn

Schools

627

dialectic and rhetoric in Latin. In dialectic, students posed questions to

each other and answered them according to basic logical propositions pro-

vided by the teacher. Rhetoric was the art of composition and speaking (in

Latin, of course).

Medieval treatises on mathematics required students to memorize tables

of addition and multiplication. Once students had memorized multiplica-

tion tables through 20 times 20, they could learn to solve problems of ap-

plied mathematics that they might face in everyday life, having to do with

prices, time, and distance. Arithmetic training also taught the use of the

abacus. Arabic numbers did not become widely used until after the close

of the Middle Ages, but especially within Italy’s strong commercial tradi-

tion, 14th-century students were taught accounting using these much sim-

pler numbers. In Italy, the abacus was the subject most taught after basic

reading.

Grammar schools in England often taught French before 1350. French

was the native language of the aristocracy for as long as 100 years after the

Norman conquest in 1066. As long as the English kings still ruled sections

of France, such as Aquitaine, they needed to speak French well, and some-

times they were raised on the Continent. They commonly married French

princesses, which refreshed the supply of native French speakers at the En-

glish court. Boys who wanted to work in any capacity at court needed to

speak French passably well. French teachers could be natives of France or

Englishmen who had been taught in French monastery schools. Some later

French teachers wrote beginning lesson books, perhaps as an advertisement

for their services. But after the Black Death plague, teaching French fell

off sharply. It became very diffi cult to fi nd teachers, and all but the highest-

class schools gave up.

Masters whipped boys for being late, not paying attention, or making

mistakes. They used thin rods of birch and other pliant wood. Most school-

ing involved a great deal of whipping, although reformers like Saint Anselm

wrote educational tracts that recommended kindness.

Schools, both grammar schools and colleges, observed the liturgical cal-

endar with its many holidays, both fasts and feasts. English schools appear

to have followed a schedule of four terms, modifi ed to three by eventually

dropping the summer term. The fall term began at Michaelmas, the winter

term after Christmas, and the spring term after Easter. It is likely that boys

went home for a few weeks between terms. Christmas included a holiday

that was exclusively for the boys at cathedral schools. They elected a boy

bishop and enjoyed making parodies of the church’s rites and presiding

over parties. Schoolboys were usually in school when Lent began and could

celebrate Shrove Tuesday their own way. In England, in addition to eating

up the meat and dairy, schoolboys held cockfi ghts.

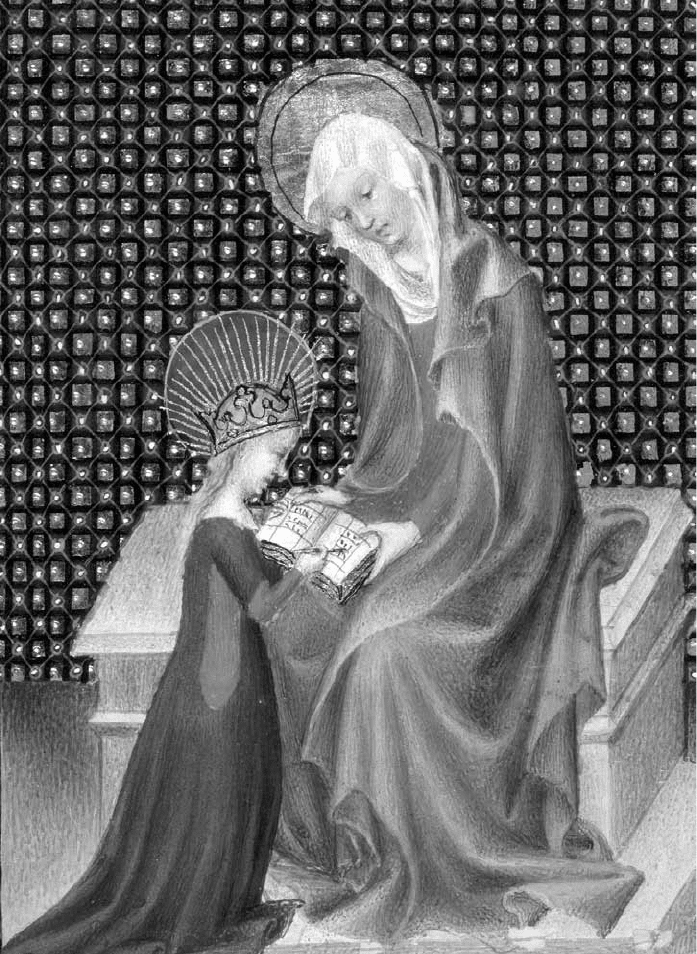

The image of the Virgin Mary as a child, learning to read at her mother’s knee, was a

popular devotional and domestic scene. Although the Bible story made it clear that

Mary was not from a wealthy family, medieval people assumed that her mother, Saint

Anne, must have been in the literate upper class. The mother and child were always

shown wearing fi ne clothes and reading from a real book. As was typical in a time of

limited seating, the little child Mary must stand while her mother sits. While it tells us

nothing about the childhood of the historical Mary, it shows what an aristocratic

medieval mother did to teach her daughter to read. Daughters rarely went to school, so

learning was handed down within the family. (The British Library/StockphotoPro)

Schools

629

Schools frequently put on plays, especially in England, but also in other

European countries. Since the schools were often under the oversight of

the church, the plays were usually miracle or mystery plays. The most pop-

ular plays illustrated the lives or miracles of saints, particularly the patron

saint of the church or town. These plays were often fi lled with gory martyr-

dom and could have been genuinely popular with the boys. Choirboys were

also part of the liturgical drama of Mass on special holidays, acting parts

like the women visiting the tomb of Jesus on Easter.

Girls did not as commonly learn to read their spoken language and even

less commonly learned Latin. Nuns may have taught some girls, singly or

in groups. Many convents had small schools for orphans under their care

and for upper-class girls who were placed there for schooling or future

entrance into the convent. Most English or French girls who learned to

read were taught at home by their mothers. It was a mark of higher social

class to have a mother who could read; in some medieval illustrations, the

Virgin Mary is shown learning her letters with her mother, Anne, who is

dressed as a noble lady. By the 15th century, a family of small landowners

expected to teach their girls to read and write. The Paston family, whose

collection of medieval letters is a resource for scholars, had several genera-

tions of women who corresponded in good English. The few women who

could read and write in French and Latin were always from noble families.

Italy’s schools were an exception to this rule. Florence records schools

for girls as well as for boys, and there are women teachers on the pay

records.

Among Jews, there was a strong tradition of fathers teaching their sons

to read Hebrew, which was used as a universal correspondence language

among Jews in different countries. In a town with a signifi cant number of

Jews, the synagogue often sponsored a school. The records of Jewish syna-

gogue schools show that they did not use punishment with young children,

but rather gave out sweets as rewards for learning. Older students were sub-

jected to beatings like their Christian peers. Some Jewish students learned

Latin as well as Hebrew and the local language.

See also: Alphabet, Babies, Jews, Music, Universities, Women.

Further Reading

Cook, T. G., ed. History of Education in Europe. New York: Routledge, 2008.

Hanawalt, Barbara A. Growing Up in Medieval London: The Experience of Child-

hood in History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Miner, John N. The Grammar Schools of Medieval England: A. F. Leach in Historio-

graphical Perspective. Montreal: McGill University Press, 1990.

Newman, Paul B. Growing Up in the Middle Ages. Jefferson, NC: McFarland,

2007.