Jan Lindhe. Clinical Periodontology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PERIODONTITIS AS A RISK FOR SYSTEMIC DISEASE • 373

Hujoel and co-workers evaluated the same popula-

tion cohort as DeStefano and colleagues but for a

longer 21-year follow-up. The Hujoel et al. study ex-

tensively adjusted for possible confounding factors,

and this may account for the lack of any detected

significant relationship after adjustment. It is also

likely that significant misclassification occurred in the

periodontal status over time, with those classified as

having no periodontal disease at baseline developing

periodontal disease over the 21 years of study. Lastly,

misclassification of those having periodontal disease

at baseline may have occurred over time as a result of

treatment and extractions (Hujoel et al. 2000).

Table 16-3 summarizes the strength and consis-

tency of associations for oral conditions as risk factors

for coronary heart disease. It is interesting to note the

consistency of the associations across studies that

used different study designs and a variety of measures

for both the exposure and outcome.

Specificity of the associations between

periodontitis and coronary heart disease

The specificity of the associations between oral condi-

tions and heart disease are summarized in Table 16-4.

The associations in these studies have been adjusted

for established risk factors for atherosclerosis and

coronary heart disease, indicating that the associa-

tions found are not confounded by those factors. The

student should remember that the criterion of speci-

ficity suggests that the condition being studied such

as periodontitis is more likely to be a risk factor if it is

specifically related to a single disease and not multiple

diseases. Data relating periodontitis as a risk for pre-

term low birthweight infants, diabetes and other sys-

temic conditions suggest that periodontitis does not

fully meet the criterion of specificity. However, it is the

combined weight of the evidence that is most impor-

tant. It is of course possible for an exposure to be a risk

factor for multiple conditions. Cigarette smoking is

one such example (Beck et al. 1998).

Correct time sequence

Table 16-5 presents data which examine the time se-

quence for an association between oral conditions and

atherosclerosis/coronary heart disease. Because the

reviewed case control studies conducted by Matilla

and co-workers (1989, 1993) selected subjects on the

basis of diagnosed coronary heart disease, they lack

information on whether periodontitis preceded the

cardiovascular diagnosis. The Matilla et al. (1995)

study is a follow-up of patients who were hospitalized

with myocardial infarction; therefore the disease was

present prior to oral status measurement. The DeSte-

fano et al. study is a cohort study so it is assumed that

any NHANES I subjects who had heart disease at

baseline were not included in the analysis. The Beck

and co-workers study enrolled only participants who

were systemically healthy, so oral disease present at

baseline did not precede the development of the car-

diovascular outcome. The outcome variable in the

Genco et al. study was new cardiovascular disease.

The outcome variable in the Joshipura et al. study was

new coronary heart disease. Thus there are at least a

few studies that meet the time sequence criterion for

establishing periodontitis as a risk for coronary heart

disease (Beck et al. 1998, Garcia et al. 2001).

Degree of exposure

The degree of exposure of the suspected risk factor is

considered important in establishing causation be-

cause increasing dose levels of the purported risk

factor or exposure should lead to increasing prob-

abilities for the disease.

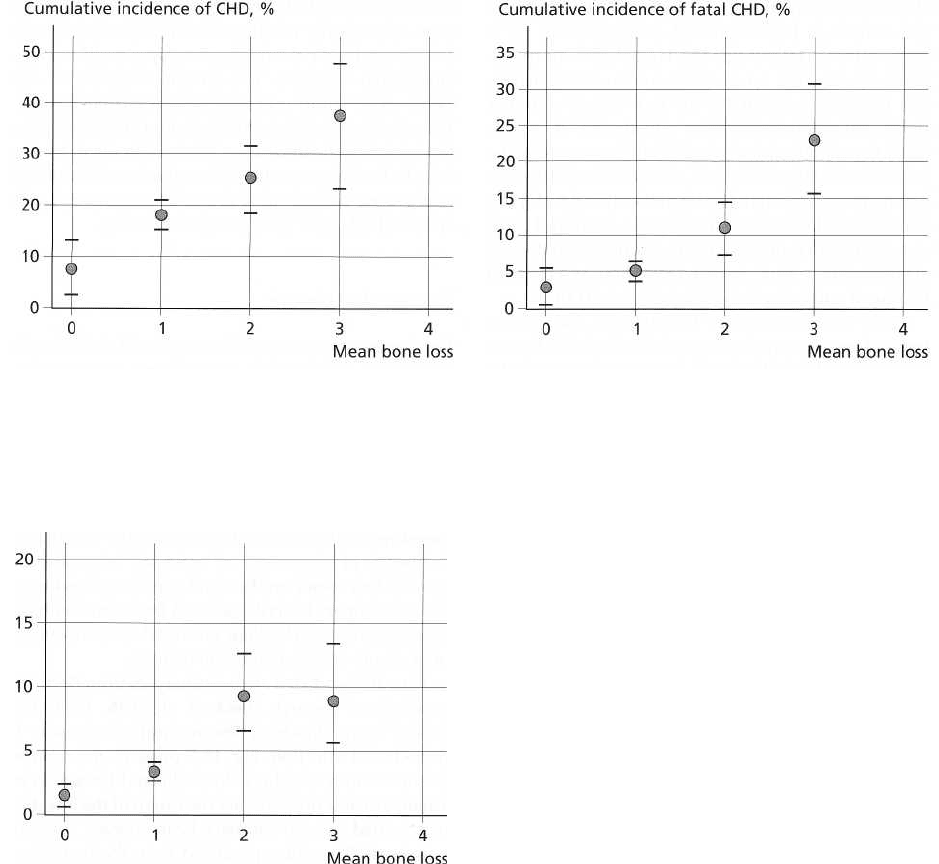

Figs. 16-4, 16-5 and 16-6 are taken from Beck and

co-workers' reports (Beck et al. 1996, 1998). One can

note that with increasing periodontitis severity as

measured with bone loss there is a higher cumulative

frequency of occurrence of coronary heart disease.

Levels of alveolar bone loss and cumulative incidence

of total coronary heart disease and fatal coronary heart

disease indicated a biologic gradient between severity

of exposure and occurrence of disease.

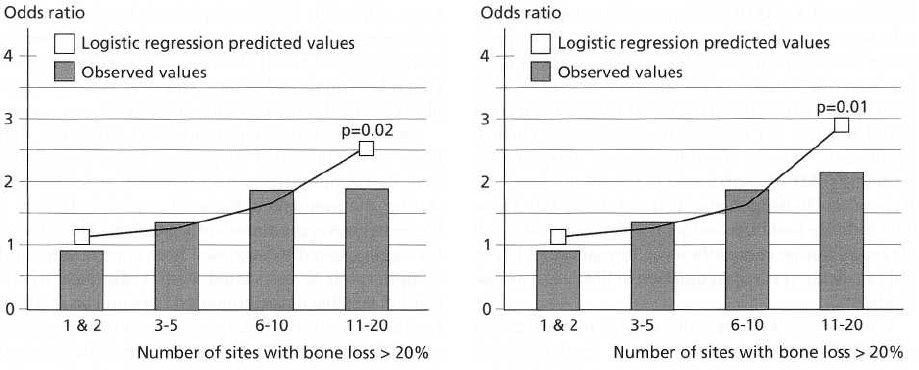

Figs. 16-7 and 16-8 are new analyses from Beck and

co-workers' research (Beck et al. 1996, 1998) that

looked more closely at the amount of exposure to

periodontal infection. Fig. 16-7 presents the number

of sites with > 20% bone loss adjusted for age in an

attempt to describe whether the extent of the infection

was related to total coronary heart disease. The line

represents the values predicted from the logistic re-

gression model, assuming a linear dose-response re-

lationship between increasing numbers of sites with

greater than 20% hone loss and total coronary heart

disease, adjusting for age. The model is significant

with a P value of 0.02 and shows that the predicted

odds ratios run from 1.04 for 1 or 2 sites up to 2.5 for

11 to 20 sites with bone loss greater than 20%.

Fig. 16-8 presents the same information, except that

the relationship between the number of sites of bone

loss and total coronary heart disease was adjusted for

all relevant risk factors. Both figures provide support

for a dose-response gradient between extent of peri-

odontal bone loss and coronary heart disease inde-

pendent of other known risk factors.

Arbes et al. (1999) recently evaluated the associa-

tion between periodontal disease and coronary heart

disease in the third National Health and Nutrition

Examination Survey (NHANES III) and found that the

odds for a history of heart attack increased with the

severity of periodontal disease. With the highest se-

verity of periodontal disease, the odds ratio was 3.8

(

95% confidence interval; 1.5-9.7) as compared to no

periodontal disease after adjustment for age, gender,

race, poverty, smoking, diabetes, high blood pressure,

374 • CHAPTER

16

None

20% 40% 60% 80%

N=74 N=812 N=199 N=31

N=2

Fig. 16-4. Age-adjusted level of bone loss and cumula

-

tive incidence of coronary heart disease.

Cumulative incidence of stroke, %

None

20% 40% 60% 80%

N=74 N=812 N=199 N=31

N=2

Fig. 16-6. Age-adjusted level of bone loss and cumula

-

tive incidence of stroke.

body mass index and serum cholesterol. This cross-

sectional study adds additional evidence for an asso-

ciation seen in the Beck et al. (1996) study, and shows

a dose response with high levels of periodontal dis-

ease associated with higher prevalence of reported

heart attack.

Biological plausibility

It has been particularly helpful in the ongoing study

of risk to try to understand the "biologic plausibility"

or scientific logic that would explain a link between

periodontitis and atherosclerosis/coronary heart dis-

ease. As noted earlier, for many years infection has

been suspected as a risk factor for atherosclerosis and

coronary heart disease (Thorn et al. 1992, Loesche

1994, Danesh et al. 1997). Other suspected etiologic

None

20% 40% 60% 80%

N=74 N=812 N=199 N=31

N=2

Fig. 16-5. Age-adjusted level of bone loss and cumula

tive incidence of fatal coronary heart disease.

infectious agents in atherogenesis include cytomega-

lovirus, herpes virus,

H. pylori

and C.

pneumonice.

The

inflammatory response to these infections, and the

large body of evidence on inflammatory pathways in

atherogenesis, certainly provide reasons to believe

that

the inflammation resulting from periodontal in-

fection and periodontitis may contribute to coronary

heart disease (Beck et al. 1998, Ross 1999).

Several investigators have suggested that there is

marked variability in individual host responses to

bacterial challenge with periodontitis (Offenbacher

1996, Beck et al. 1998, Page 1998a,b). Such variability

has been attributed to individual differences in T cell

and monocyte functions, with such differences in part

having a genetic basis. Some individuals may respond

to a microbial or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge

with an abnormally high inflammatory response, as

reflected in the release of high levels of pro-inflamma-

tory mediators such as PGE

2

, IL-1(3, and TNF-u. In

laboratory tests, peripheral blood monocytes from

these hyperinflammatory monocyte phenotype pa-

tients secrete three-fold to ten-fold greater amounts of

these mediators in response to LPS than those from

normal monocyte phenotype individuals. Such obser-

vations have led to the hypothesis that the variation

in inflammatory responses may be a direct conse-

quence of at least two factors: those genes that regulate

the T cell-monocyte response, and the host-microbial

environment, which can trigger and modulate the

response (Offenbacher 1996, Beck et al. 1998, Page

1998a,b).

Beck, Offenbacher and colleagues propose that the

natural histories of both periodontitis and coronary

heart disease/atherosclerosis may in fact be related to

a common hyper-reactive inflammatory phenotype or

response. They further list several pathogenic charac-

teristics shared by the two diseases (Beck & Offen-

bacher 1998, Beck et al. 1998, Offenbacher et al. 1999):

PERIODONTITIS AS A RISK FOR SYSTEMIC DISEASE • 375

Fig. 16-7. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for

number of sites with > 20% bone loss and total coro-

nary heart disease adjusted for age.

1.

Cells of the monocytic lineage and the attendant

cytokines play a critical role in initiating and propa

-

gating both atheroma formation and periodontitis.

2.

The hyper-inflammatory phenotype appears to be

under both genetic and environmental influence.

Monocytic hyper-responsiveness to LPS has been

genetically mapped tentatively to the area of HLA-

DR3/3 or -DQ which is the region where increased

susceptibility to Type 1 diabetes mellitus has been

proposed to reside. Furthermore, dietary-induced

elevation of serum low-density lipoprotein has

been shown to upregulate monocytic responses to

LPS, thereby providing a behavorial or environ-

mental influence on the macrophage phenotype.

Known risk factors for coronary heart disease such

as dietary fat intake may therefore enhance mono

-

cyte secretion of inflammatory and tissue destruc-

tive cytokines, and via this common mechanism,

may contribute to the severity of the expression of

coronary heart disease and periodontal disease.

3.

Periodontal infections may directly contribute to

the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and throm-

boembolic events by providing repeated systemic

challenges with LPS and inflammatory cytokines.

There is also evidence that some of the bacteria found

in dental plaque may have a direct effect on

atherosclerosis and thromboembolic events. Herzberg

and co-workers have reported that the oral Gram-

positive bacterium S.

sanguis

and the Gram-negative

periodontal pathogen

P.

gingivalis

have been shown to

induce platelet aggregation and activation through

the

expression of collagen-like platelet aggregation-

associated proteins. The aggregated platelets may

then play a role in atheroma formation and throm-

boembolic events (Herzberg et al. 1983, Herzberg &

Meyer 1996, 1998).

A recent study by Haraszthy et al. identified peri-

odontal pathogens in human carotid atheromas

Fig. 16-8. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for

number of sites with > 20% bone loss and total coro

-

nary heart disease adjusted for age and other relevant

risk factors.

(Haraszthy et al. 2000). Fifty carotid atheromas ob-

tained at endarterectomy were analyzed for the pres-

ence of bacterial 16-S rDNA by PCR using synthetic

oligonucleotide probes specific for the periodontal

pathogens A.a.,

B. forsythus, P. gingivalis

and

P.

interme-

dia.

Thirty per cent of the specimens were positive for

B. forsythus,

26% positive for

P.

gingival is,

18% positive

for A.

a.

and 14% positive for

P.

intermedia. Chlamydia

pneumoniae

DNA was detected in 18% of the athero-

mas. These and other studies suggest that periodontal

pathogens may be present in atherosclerotic plaques,

where, like other infectious organisms, they may play

a

role in atherogenesis (Genco et al. 1999).

Experimental evidence

There is ongoing research to see if well-controlled

prospective studies in animal models and in human

subjects can confirm or extend the evidence for a role

for periodontitis as a risk for systemic disease. Beck

and co-workers (1998) have studied the effects of P.

gingivalis

infection and high-fat diets in atheroma for-

mation in mice. Using a knock-out mouse model ge-

netically susceptible to cardiovascular disease (het-

erozygotic APOE), animals were given a high-fat or

low-fat diet. Small steel coil chambers were implanted

subcutaneously and the rejection of the chambers after

inoculation with

P.

gingivalis

HG405 was examined.

The animals were first immunized with a dose of

heat-killed

P.

gingivalis

and 21 days later challenged

with live

P.

gingivalis.

The sloughing of the chamber

would represent an intense inflammatory reaction to

the infectious agent. Initial findings suggest that a

high-fat diet in the susceptible mouse strain was asso

-

ciated with a tendency to exhibit increased risk of

serious inflammation. This initial study at least links

dietary fat intake in a susceptible mouse to an inflam

-

matory response to a periodontal pathogen,

P.

gingi-

376 • CHAPTER 16

valis.

Geva et al. (2000) in this group have reported that

infection of mice with a more virulent P.

gingivalis

strain leads to increased atheroma size and calcifica-

tion with the amount of calcification increasing with

the length of exposure. In no instance was calcification

found in mice not exposed to

P.

gingivalis.

Further,

significantly greater amounts of bone morphogenic

protein-2 (BMP-2) were found in the atheromas of the

P.

gingivalis

challenged mice (Chung et al. 2002). These

data indicate that infection with a virulent strain of P.

gingivalis

can promote atheroma formation and arte-

rial calcification via up-regulation of BMPs in a mouse

model.

When one looks at the collective evidence gathered

so far, it seems clear that, at least from historical

epidemiological data, there is a compelling link be-

tween periodontitis and coronary heart disease. There

are also emerging data which strongly suggest that

period ontitis may be a risk for pregnancy complica-

tions such as preterm low birthweight infants.

PERIODONTITIS AS A RISK FOR

PREGNANCY COMPLICATIONS

Beginning around 1996, with a landmark report by

Offenbacher and colleagues (Offenbacher et al. 1996),

there has been an increasing interest and much re-

search into whether periodontitis may be a possible

risk factor for preterm low birthweight infants.

Preterm infants who are born with low birth-

weights represent a major social and economic public

health problem, even in industrialized nations. Al-

though there has been an overall decline in infant

mortality in the US over the past 40 years, preterm low

birthweight remains a significant cause of perinatal

mortality and morbidity. Accordingly, a 47% decrease

in the infant mortality rate to a level of 13.1 per 1000

live births occurred between 1965 and 1980, but the

mortality rate and the incidence of preterm delivery

have not significantly changed since the early 1990s

(

Offenbacher et al. 1996, 1998, Champagne et al. 2000).

Preterm low birthweight deliveries represent ap-

proximately 10% of annual births in industrialized

nations and account for two-thirds of overall infant

mortality. Approximately one-third of these births are

elective while two-thirds are spontaneous preterm

births. About a half of the spontaneous preterm births

are due to premature rupture of membranes and the

other half are due to preterm labor. For the spontane-

ous preterm births, 10-15% occur before 32 weeks

gestation, result in very low birthweight (< 1500 g) and

often cause long-term disability, such as chronic respi

-

ratory diseases and cerebral palsy (Offenbacher et al.

1996, 1998, Champagne et al. 2000).

Among the known risk factors for preterm low

birthweight deliveries are young maternal age (< 18

years) drug, alcohol and tobacco use, maternal stress,

genetic background, and genitourinary tract infec

tions. Although 25-50% of preterm low birthweight

deliveries occur without any known etiology, there is

increasing evidence that infection may play a signifi-

cant role in preterm delivery (Hill 1998, Goldenberg et

al. 2000, Sobel 2000, Williams et al. 2000).

One of the more important acute exposures that

have been implicated in preterm birth is an acute

maternal genitourinary tract infection at some point

during the pregnancy. Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a

Gram-negative, predominantly anaerobic infection of

the vagina, usually diagnosed from clinical signs and

symptoms. It is associated with a decrease in the

normal lactobacillus-dominated flora and an increase

in anaerobes and facultative species including

Gard-

nerella vaginalis, Mobiluncus curtsii, Prevotella bivia

and

Bacteroides ureolyticus.

Bacterial vaginosis is a rela-

tively common condition that occurs in about 10% of

all pregnancies. It may ascend from the vagina to the

cervix and even result in inflammation of the mater-

nal-fetal membranes (chorioamnionitis). Extending

beyond the membranes, the organisms may appear in

the amniotic fluid compartment that is shared with the

fetal lungs and/or may involve placental tissues and

result in exposure to the fetus via the bloodstream.

Despite the observed epidemiological linkage of bac-

terial vaginosis with preterm birth, the results from

randomized clinical trials to determine the effects of

treating bacterial vaginosis with systemic antibiotics

on incident preterm birth are equivocal (Goldenberg

et al. 2000). Still, there are compelling data linking

maternal infection and the subsequent inflammation

to preterm birth. It appears that inflammation of the

uterus and membranes represents a common effector

mechanism that results in preterm birth, and thus,

either clinical infection or subclinical infection is a

likely stimulus for increased inflammation.

In the early 1990s, Offenbacher and his group hy-

pothesized that oral infections, such as periodontitis,

could represent a significant source of both infection

and inflammation during pregnancy. Offenbacher

noted that periodontal disease is a Gram-negative

anaerobic infection with the potential to cause Gram

-

negative bacteremias in persons with periodontal dis

-

ease. He hypothesized that periodontal infections,

which serve as reservoirs for Gram-negative anaero-

bic organisms, lipopolysaccharide (LPS, endotoxin)

and inflammatory mediators including PGE

2

and

TNF-a, may be a potential threat to the fetal-placental

unit (Collins et al. 1994a,b).

As a first step in testing this hypothesis, Offen-

bacher and colleagues conducted a series of experi-

ments in the pregnant hamster animal model. It had

been noted earlier by Lanning et al. (1983) that preg-

nant hamsters challenged with E.

coli

LPS had malfor

-

mation of fetuses, spontaneous abortions and low

fetal weight. The work by Lanning and co-workers

clearly demonstrated that infections in pregnant ani-

mals could elicit many pregnancy complications in-

cluding spontaneous abortion, preterm labor, low

birthweight, fetal growth restriction and skeletal ab-

PERIODONTITIS AS A RISK FOR SYSTEMIC DISEASE • 377

normalities. It was not clear however if these findings

from E. coif endotoxin would be similar if endotoxin

from oral anaerobes was studied. First of all, LPS from

Gram-negative enteric organisms differs in structure

and biological activity from oral LPS. Thus, Offen-

bacher needed to demonstrate that LPS from oral

organisms had similar effects on fetal outcomes when

administered to pregnant animals. Secondly, the oral

cavity represents a distant site of infection. Although

pneumonia has been a recognized example of a dis-

tant site of infection triggering maternal obstetric

complications, it was important to demonstrate that

distant, non-disseminating infections with oral patho

-

gens could elicit pregnancy complications in animal

models. Thirdly, oral infections are chronic in nature.

Increased obstetric risk is generally associated with

acute infections that occur during pregnancy. Thus, in

concept, maternal adaptation to a chronic infectious

challenge was assumed to afford protection to the

fetus, even during acute flare-ups that may occur

during pregnancy.

Offenbacher's landmark hamster studies (Collins

et

al. 1994a,b) demonstrated that chronic exposure to

oral pathogens like

P. gingivalis

in a chamber model

(

Genco & Arko 1994) does not in fact afford protection,

but actually enhances the feto-placental toxicity of

exposure during pregnancy. Thus during pregnancy

the mother does not become "tolerant" of infectious

challenge from oral organisms. Offenbacher also

wanted to demonstrate that the low-grade infections

with low numbers of oral pathogens were not of suf-

ficient magnitude to induce maternal malaise or fever.

He noted however a measurable local increase of PG

E

2

and TNF-a in chamber fluid with

P. gingivalis

infection

as well as a 15-18% decrease in fetal weight. Further,

the magnitude of the PGE

2

and TNF-a response was

inversely related to the weight of the fetuses, mimick-

ing the intra-amniotic changes seen in humans with

preterm low birthweight. LPS dosing experiments

demonstrated that higher levels of LPS could induce

fever and weight loss in pregnant animals and re-

sulted in more severe pregnancy outcomes including

spontaneous abortions and malformations. These

more noteworthy outcomes were not seen in the low

challenge-oral infection models, but rather resulted in

a consistent decrease in fetal weight. Previous sensiti-

zation or exposures to these pathogens prior to preg-

nancy enhanced the severity of the fetal growth re-

striction when a secondary exposure occurred during

pregnancy.

Offenbacher and colleagues then went on to study

infection and pregnancy in the hamster by experimen

-

tally inducing periodontal disease in the animal

model (Collins et al. 1994b). Four groups of animals

were fed either control chow or plaque-promoting

chow for an 8-week period to induce experimental

periodontitis prior to mating. Two additional groups

of animals (i.e. one control chow and one plaque-pro-

moting chow) received exogenous

P. gingivalis

via oral

gavage. Animals fed the plaque-promoting diet begin-

ning 8 weeks prior to mating developed periodontitis.

These animals also had litters with a mean fetal weight

of 1.25 ± 0.07 g that was 81% of the weight of the

control groups. Animals receiving both plaque-pro-

moting diet and

P. gingivalis

gavage also had signifi-

cantly smaller fetuses. The mean fetal weight for this

group was 1.20 ± 0.19 g which represented a signifi-

cant 22.5% reduction in fetal weight compared to

controls. Exogenous

P. gingivalis

challenge by gastric

gavage did not appear to promote either more severe

periodontal disease or more severe fetal growth re-

striction. This experiment indicated that experimen-

tally induced periodontitis in the hamster could also

alter fetal weight in the hamster.

Other factors appear also to be involved in the

findings of low fetal weight in the hamster study.

There was a statistically significant elevation of intra-

amniotic fluid levels of both PGE

2

and TNF-a. This

finding suggests that periodontal infection can result

in a change in the fetal environment. It is possible that

both PGE

2

and TNF-a are produced by the periodon-

tium and appear in the systemic circulation to even-

tually cross the chorioamniotic barrier and finally

appear in the fluid. It is more likely, however, that

blood-borne bacterial products such as endotoxin tar

-

get the chonoamniotic plexus to trigger local PG

E

2

and

TNF-a synthesis. These animal studies by Offen-

bacher and colleagues provided important proof-of-

concept experiments and raised the possibility that

distant, low grade oral infections might also trigger

inflammation of the human maternal-fetal unit in a

manner analogous to that seen with reproductive tract

infections (Collins et al. 1994a,b).

In a subsequent landmark study, Offenbacher and

colleagues conducted a case-control study on 124

pregnant or postpartum women (Offenbacher et al.

1996). Preterm low birthweight cases were defined as

a mother whose infant had a birthweight of less than

2500 g and also had one or more of the following:

gestational age < 37 weeks, preterm labor or preterm

premature rupture of membranes. Controls were all

mothers whose infant had a normal birthweight. As-

sessments included a broad range of known obstetric

risk factors such as tobacco usage, drug use and alco

-

hol consumption, level of prenatal care, parity, geni-

tourinary tract infections and weight gain during

pregnancy. Each subject received a full-mouth peri-

odontal examination to determine clinical attachment

levels. Mothers of preterm low birthweight cases and

first birth PLBW cases had significantly more ad-

vanced periodontal disease as measured with attach-

ment loss than the respective mothers of normal birth

-

weight controls. Multivariate logistic regression mod-

els, controlling for other known risk factors and co-

variates, demonstrated that periodontitis was a statis

-

tically significant risk factor for preterm low birth-

weight, with adjusted odds ratios of 7.9 and 7.5 for all

PLBW cases and primiparous PLBW cases respec-

tively. This research by Offenbacher and colleagues

was the first to demonstrate an association between

378 • CHAPTER

16

periodontal infection and adverse pregnancy out-

comes in humans (Offenbacher et al. 1996).

Jeffcoat and Hauth have recently confirmed this

association in a larger case-control study. Gathering

data on 1313 mothers, Jeffcoat and Hauth reported

that maternal periodontitis was an independent risk

factor for preterm birth. With increasing severity of

periodontal disease as an exposure, there was an in-

creased risk for preterm birth with odds ratios ranging

from 4.45 to 7.07 for moderate to severe periodontitis,

adjusting for age, race, smoking and parity (Jeffcoat et

al. 2001a,b).

Offenbacher's group at the University of North

Carolina has been conducting a large prospective mo-

lecular epidemiological study designed to examine

the

role of maternal periodontal infections on abnor

mal

pregnancy outcomes. The principal goal of the

study

is to determine whether the presence of mater

nal

periodontal disease represents a significant inde-

pendent risk factor for preterm birth and low birth-

weight in the context of other established risk factors.

Maternal periodontal disease was assessed at baseline

(prior to 26 weeks gestation) and at postpartum to

examine for periodontal disease progression during

pregnancy. This group measured periodontal disease

as an exposure in three ways: (1) clinical signs — by

assessment of disease extent and severity (Carlos et al.

1986), (2) inflammatory response — by concentrations

of inflammatory mediators (PGE

2

and IL-1(3) within

the gingival crevicular fluid (GCF), and (3) microbial

burden — by determining levels of periodontal patho-

gens. Serum antibody responses to specific oral organ

-

isms were also measured. Extensive maternal obstet-

ric data were collected including medical, social and

clinical OB histories. The presence of bacterial vagi-

nosis as a potential covariate or confounder was as-

sessed by clinical exam, history and quantitative ex-

amination of the composition of the vaginal flora by

wet mount, Gram stain and whole chromasomal DNA

macroarray for specific indicator vaginal and cervical

organisms. Neonatal exposures and outcomes were

determined including fetal cord blood measures of

antibody to oral organisms and levels of inflammatory

mediators. Data have to date been collected in over

1200 mothers.

The findings from this large prospective cohort

study very nicely confirm and extend the case-control

observations that Offenbacher reported earlier. At

baseline, periodontal disease independently enhances

the risk of preterm birth, e.g. for moderate-severe

disease adjusted odds ratio = 3.0 for GA< 37 weeks

and odds ratio of 7.9 adjusting for race, age, socio-eco

-

nomic status, smoking, parity, bacterial vaginosis and

chorioamnionitis (Lieff et al. 2000). In addition, peri-

odontal disease increased the relative risk for fetal

growth restriction (decreased weight for gestational

age, adjusting for parity, race and baby sex) as well as

pregnancy-induced hypertension, preeclampsia and

neonatal death.

Of particular interest in this ongoing study is the

finding that not only does the presence of periodontal

disease early in pregnancy appear to confer risk, but

also if periodontal disease becomes more severe dur-

ing pregnancy, this periodontitis worsening inde-

pendently enhances the risk of preterm birth. When

periodontal disease is present both at baseline and

also progressing during pregnancy the odds ratio for

preterm birth is 10.9 adjusting for age, race, previous

preterm births, parity, smoking and social status (Lieff

et al. 2000). Clinical diagnosis of vaginosis or subclini

-

cal vaginosis chorioamnionitis did not confound the

relationship between periodontal disease and preterm

birth. Complementing these recent epidemiologic

findings, Madianos et al. (2002) have presented initial

findings of fetal immunoglobulin (IgM) specific for

periodontal pathogens. Although they detected IgM

specific to

P.

giiigivalis

and

B. fobs/thus,

among others,

in

fetal cord blood samples from both low and normal

birthweight infants, these preliminary data at least

confirm that the fetus can be challenged by maternal

periodontal bacteria and can mount an independent

host response.

PERIODONTITIS AS A RISK FOR

DIABETIC COMPLICATIONS

Similar to cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus is

a

common, multifactorial disease process involving

genetic, environmental and behavioral risk factors.

Affecting up to 5% of the general population and over

124 million persons worldwide (King et al. 1998), this

chronic condition is marked by defects in glucose

metabolism that produce hyperglycemia in patients.

Diabetes mellitus is broadly classified under two ma-

jor types (American Diabetes Association Expert

Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Dia

-

betes Mellitus 1997). In patients with Type 1 diabetes,

(formerly called insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus),

the defect occurs at the level of the pancreatic beta cells

that are destroyed. Consequently Type 1 diabetics

produce insufficient levels of the hormone insulin for

homeostasis. In contrast, patients with Type 2 diabetes

(formerly called non-insulin-dependent diabetes mel-

litus), exhibit the defect at the level of the insulin

molecule or receptor. Cells in Type 2 diabetics cannot

respond or are resistant to insulin stimulation. Diabe

-

tes mellitus is usually diagnosed via laboratory fast-

ing blood glucose levels that are greater than 126

mg/dL. Additionally, casual or non-fasting blood glu-

cose values are elevated above 200 mg/dL. Thirdly,

diabetic patients exhibit abnormal glucose tolerance

tests (i.e. blood glucose levels greater than 140 mg/dL

at 2 hours following a 100 g glucose load). Elevated

glycated hemoglobin levels (HbAI and HbA1c) com-

prise a fourth laboratory parameter and one that pro-

vides a 30 to 90-day record of the patient's glycemic

status. Classic signs and symptoms of diabetes in-

clude polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, pruritis,

PERIODONTITIS AS A RISK FOR SYSTEMIC DISEASE •

379

weakness and fatigue. End-stage diabetes mellitus is

characterized by problems with several organ systems

including micro and macro-vascular disease (athero-

sclerosis), retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy and

indeed periodontal disease.

Although environmental exposures, viral infection,

autoimmunity and insulin resistance are currently

considered to play principal roles in the etiology of

diabetes mellitus (Yoon 1990, Atkinson & Maclaren

1990), pathogenesis of the disease and end-organ

damage relies heavily on the formation and accumu-

lation of advanced glycation end products (AGES)

(

Brownlee 1994). Accordingly, the chronic hyperglyce-

mia in diabetes results in the non-enzymatic and irre

-

versible glycation of body proteins. These AGES, in

turn, bind to specific receptors for advanced glycation

end products (RAGEs) on monocytes, macrophages

and endothelial cells, and alter intracellular signaling

(

transduction) pathways (Esposito et al. 1992, Kirstein

et al. 1992). With AGE-RAGE binding, monocytes and

macrophages are stimulated to proliferate, up-regu-

late pro-inflammatory cytokines and produce oxygen

free radicals (Vlassara et al. 1988, Yan et al. 1994, Yui

et al. 1994). While oxygen free radicals directly dam-

age host tissues, pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1,

IL-6 and TNF-a exacerbate this damage via a cascade

of catabolic events and the recruitment of other im-

mune cells (T and B lymphocytes). Patients with dia-

betes exhibit elevated levels of AGES in tissues includ

-

ing those of the periodontium (Brownlee 1994,

Schmidt et al. 1998). Diabetics also present with ele-

vated serum and gingival crevicular fluid levels of

pro-

inflammatory cytokines (Nishimura et al. 1998, Salvi

et al. 1998). Furthermore, monocytes isolated

from

diabetics and stimulated with LPS secrete higher

concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines and

Prostaglandins (Salvi et al. 1998). Chronic hyperglyce

-

mia, the accumulation of AGEs and the hyper-inflam

-

matory response may promote vascular injury and

altered wound healing via increased collagen cross-

linking and friability, thickening of basement mem-

branes and altered tissue turnover rates (Weringer &

Arquilla 1981, Lien et al. 1984, Salmela et al. 1989,

Cagliero et al. 1991). Lastly, diabetic patients exhibit

impairments in neutrophil chemotaxis, adherence

and phagocytosis, (Bagdade et al. 1978, Manoucherhr

-

Pour et al. 1981, Kjersem et al. 1988) and thus are at

high risk for infections like periodontitis.

Numerous epidemiologic surveys demonstrate an

increased prevalence of periodontitis among patients

with uncontrolled or poorly controlled diabetes mel-

litus. For example, Cianciola et al. (1982) reported that

13.6% and 39% of Type 1 diabetics, 13-18 and 19-32

years of age respectively, had periodontal disease. In

contrast, none of the non-diabetic sibling controls and

2.5% of the non-diabetic, unrelated controls exhibited

clinical evidence of periodontitis. In a classic study,

Thorstensson and Hugoson (1993) examined the se-

verity of periodontitis in patients with diabetes melli-

tus and compared severity of periodontitis with the

duration a patient had been diagnosed with diabetes.

In looking at three age cohorts, 40-49 years, 50-59 years

and 60-69 years, the 40-49 years age group diabetics

had more periodontal pockets >_ 6 mm and more ex-

tensive alveolar bone loss than non-diabetics. In this

same age group, there were also more subjects with

severe periodontal disease experience among the dia-

betics than among the non-diabetics. In noting that the

younger age diabetics had more periodontitis than the

older age diabetics, these authors reported that early

onset of diabetes is a much greater risk factor for

periodontal bone loss than mere disease duration.

Safkan-Seppala & Ainamo (1992) conducted a cross-

sectional study of 71 Type 1 diabetics diagnosed with

the condition for an average of 16.5 years. Diabetics

identified with poor glycemic control demonstrated

significantly more clinical attachment loss and radio-

graphic alveolar bone resorption as compared to well-

controlled diabetics with the same level of plaque

control. Two longitudinal cohort studies monitoring

Type 1 diabetics for 5 and 2 years respectively docu-

mented significantly more periodontitis progression

among diabetics overall and among those poorly con-

trolled (Sappala et al. 1993, Firath 1997). Investigators

from the State University of New York at Buffalo have

published a number of landmark papers document-

ing the periodontal status of Pima Indians, a popula-

tion with a high prevalence of Type 2 diabetes melli-

tus. Shlossman et al. (1990) first documented the peri

-

odontal status of 3219 subjects from this unique popu

lation. Diagnosing Type 2 diabetes with glucose toler-

ance tests, the investigators found a higher prevalence

of clinical and radiographic periodontitis for diabetics

versus non-diabetics independent of age. This inves-

tigative group next focused on a cross-sectional analy

-

sis of 1342 dental subjects (Emrich et al. 1991). A

logistic regression analysis indicated that Type 2 dia-

betics were 2.8 times more likely to exhibit clinical

attachment loss and 3.4 times more likely to exhibit

radiographic alveolar bone loss indicative of perio-

dontitis relative to non-diabetic controls. In a larger

study of 2273 Pima subjects, 60% of Type 2 diabetics

were affected with periodontitis versus 36% of non-

diabetic controls (Nelson et al. 1990). When a cohort

of 701 subjects with little or no evidence of periodon-

titis at baseline were followed for approximately 3

years, diabetics were 2.6 times more likely to present

with incident alveolar bone resorption as compared to

non-diabetics. Taylor et al. (1998a,b) similarly re-

ported higher odds ratios of 4.2 and 11.4 for the risk of

progressive periodontitis among diabetic Pima Indi-

ans in general and poorly controlled diabetics (i.e.

with glycated hemoglobin levels > 9%) respectively.

The studies cited above reiterate diabetes as a modi

fier or risk factor for periodontitis. Recently, new data

have emerged indicating that the presence of perio-

dontitis or periodontal infection can increase the risk

for diabetic complications, principally poor glycemic

control. Taylor et al. (1996) first tested this hypothesis

using longitudinal data on 88 Pima subjects. Severe

38o •

CHAPTER

16

periodontitis at baseline as defined clinically or ra-

diographically was significantly associated with poor

glycemic control (glycated hemoglobin > 9%). Other

significant covariates in the regression modeling in-

cluded subject age, smoking, and baseline severity

and duration of Type 2 diabetes. Given these findings

the next logical question is whether periodontal treat-

ment can improve glycemic control. Several investiga-

tors have sought to answer this question using peri-

odontal mechanical treatment as the intervention

(

Seppala & Ainamo 1994, Aldridge et al. 1995, Smith

et al. 1996, Christgau et al. 1998, Stewart et al. 2001).

These studies in general have failed to detect an im-

provement in glycated hemoglobin level with scaling

and root planing alone. Grossi et al. (1997) reported

more compelling findings from an intervention trial

featuring 113 Pima Indians with Type 2 diabetes and

periodontitis who received both mechanical and an-

timicrobial treatment. At baseline, participants were

treated with scaling and root planing plus one of five

antimicrobial regimens: (1) water (placebo) rinse and

peroral doxycycline (100 mg q.d. for 2 weeks), (2)

0.

12`% chlorhexidine rinse and peroral doxycycline, (3)

povidone-iodine rinse and peroral doxycycline, (4)

0.

12% chlorhexidine rinse and peroral placebo, or (5)

povidone-iodine rinse and peroral placebo. Subjects

were evaluated using clinical, microbiological and

laboratory parameters prior to therapy and at 3 and 6

months. All treatment groups on average demon-

strated clinical and microbiological improvements;

however, those groups treated with adjunctive peroral

tetracycline exhibited significant and greater reduc-

tions in pocket depth and subgingival detection rates

for

P.

Ring=ivalis

as compared to the groups receiving

peroral placebo. Most strikingly, diabetic subjects re-

ceiving mechanical therapy plus peroral tetracycline

demonstrated significant, 10% reductions in their gly

-

cated hemoglobin levels. Two small, uncontrolled co-

hort studies with nine Type 1 diabetic-periodontitis

patients each similarly reported improvements in gly-

cemic control with combination mechanical-antimi-

crobial therapy (Williams & Mahan 1960, Miller et al.

1992). These limited lines of evidence suggest that

untreated periodontal infections may increase a dia-

betic patient's risk for poorer glycemic control and

subsequent systemic complications.

PERIODONTITIS AS A RISK FOR

RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS

There is lastly emerging evidence that in certain at risk

populations, periodontitis and poor oral health may

be associated with several respiratory conditions. Res

-

piratory diseases contribute considerably to morbid-

ity and mortality in human populations. Lower respi-

ratory infections were ranked as the third most com-

mon cause of death worldwide in 1990, and chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease was ranked sixth

(

Scannapieco 1999).

Bacterial pneumonia is either community-acquired

or hospital-acquired (nosocomial). Community-ac-

quired pneumonia is usually caused by bacteria that

reside on the oropharyngeal mucosa, such as

Strepto-

coccus

puculuouia

and

Haernophilus influenza.

Alterna-

tively, hospital-acquired pneumonia is often caused

by bacteria within the hospital or health care environ

-

ment, such as Gram-negative bacilli,

Pseudomonas

aeruginosa

and

Staphylococcus aureus

(Scannapieco

1999). As many as 250 000 to 300 000 hospital-acquired

respiratory infections occur in the US each year with

an estimated mortality rate of about 30%. Pneumonia

also contributes to a significant number of other

deaths by acting as a complicating or secondary factor

with other diseases or conditions.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is

another common severe respiratory disease charac-

terized by chronic obstruction to airflow with excess

production of sputum resulting from chronic bronchi

-

tis and/or emphysema. Chronic bronchitis is the re-

sult of irritation to the bronchial airway causing an

expansion of the propagation of mucus-secreting cells

within the airway epithelium. These cells secrete ex-

cessive tracheobronchial mucus sufficient to cause

cough with expectoration for at least 3 months of the

year over two consecutive years. Emphysema is the

distention of the air spaces distal to the terminal bron

-

chiole with destruction of the alveolar septa (Scan-

napieco 1999).

Beginning in 1992 with a report by Scannapieco's

group at SUNY-Buffalo (Scannapieco et al. 1992), sev

-

eral investigators have hypothesized that oral and/or

periodontal infection may increase the risk for bacte-

rial pneumonia or COPD.

It seems quite plausible from all the evidence re-

viewed in this chapter that the oral cavity may also

have a critical role in respiratory infections. For exam

-

ple, oral bacteria from the periodontal pocket can be

aspirated into the lung to cause aspiration pneumo-

nia. The teeth may also serve as a reservoir for respi-

ratory pathogen colonization and subsequent noso-

comial pneumonia. Typical respiratory pathogens

have been shown to colonize the dental plaque of

hospitalized intensive care and nursing home pa-

tients. Once established in the mouth, these pathogens

may be aspirated into the hung to cause infection. Also,

periodontal disease-associated enzymes in saliva may

modify mucosal surfaces to promote adhesion and

colonization by respiratory pathogens, which are then

aspirated into the lungs. These same enzymes may

also destroy salivary pellicles on pathogenic bacteria

to hinder their clearance from the mucosal surface.

Lastly, cytokines originating from periodontal tissues

may alter respiratory epithelium to promote infection

by respiratory pathogens (Scannapieco 1999).

At present, cross-sectional epidemiologic studies

from Frank Scannapieco's group in Buffalo and Cath-

erine Hayes's group in Boston are pointing to a sig-

PERIODONTITIS AS A RISK FOR SYSTEMIC DISEASE • 381

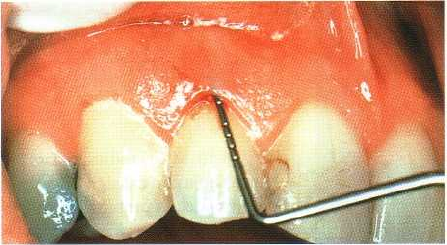

Fig. 16-9. Mean probing depth measurements of 4-5

mm have been customarily used in epidemiology stud

ies to designate a subject as being healthy or having

pe

riodontitis.

nificant association between poor oral health such as

periodontitis and pulmonary conditions. In a recent

report examining data from the third National Health

and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III),

Scannapieco and Ho reported that patients with a

history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had

significantly more periodontal attachment loss (1.48 ±

1.35 mm) than subjects without COPD (1.17 ± 1.09

mm) p = 0.0001 (Scannapieco & Ho 2001).

SUMMARY

This chapter has examined the evidence, gathered by

many investigators since the early 1990s, which sug

-

gests that periodontitis may be a risk for certain sys-

temic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, pre

-

term low-birthweight infants, diabetes mellitus and

pulmonary disease. Collectively, the findings gath-

ered for the most part from large epidemiological data

sets, are very compelling. It would certainly appear

that at the least, in a diverse group of study subjects,

periodontitis is strongly associated with systemic con

-

ditions. But there is much yet to be done to elucidate

and understand the exact nature of the relationship of

periodontitis to a person's overall risk for systemic

disease.

The student of dentistry will note that in this chap

-

ter the measures of periodontal disease used in the

epidemiological data sets were "all over the board".

Most of the studies tried to relate some type of clinical

sign of periodontitis such as pocket depth, attachment

loss or bone loss on radiographs to a systemic condi-

tion (Fig. 16-9). Two studies used self-reported disease

and asked the subject if he/she had periodontitis with

a yes/no answer. And as was noted in this chapter,

while one study might distinguish between health

and periodontitis if pocket depths were < 4mm

(

health) or >_ 4 mm (periodontitis), another study

might use 5 mm to distinguish between health and

periodontitis. Thus in one study subjects having

pocket depths of >_ 4 mm would be diagnosed with

periodontitis while in another study that subject

would have been called healthy. Further, "self-re-

ported" periodontal disease with a yes/no answer is

likely to have considerable error such that those data

may be of limited use. Still, collectively, the epidemiol

-

ogical data point to a strong and noteworthy relation

-

ship between periodontitis and systemic conditions.

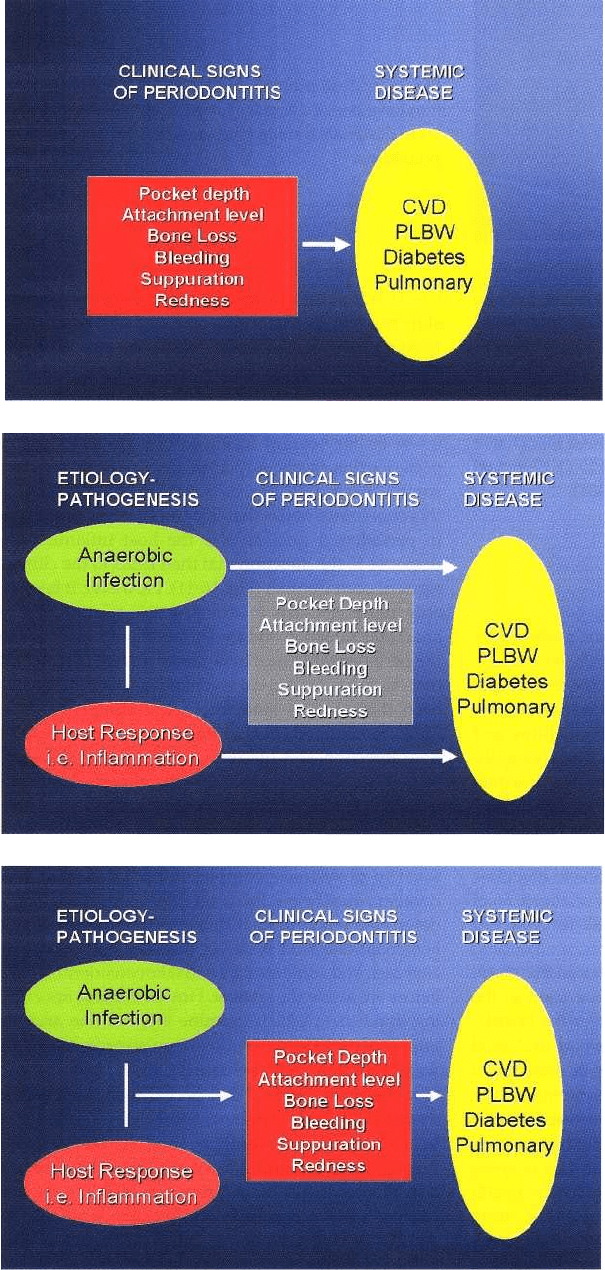

In April 2001, an AAP-NIDCR Conference was held in

Bethesda, MD, which focused on "The periodontitis-

systemic connection". One of the major points made

at this conference focused on the need for future stud

-

ies to go far beyond trying to link clinical signs of

periodontitis (such as pocket depth) with systemic

complications (Fig. 16-10). Scientists and clinicians at

this conference noted that it is the anaerobic infection

in periodontal pockets and the host inflammatory

response to the infection that then leads to the clinical

signs of periodontitis (Fig. 16-11). However, it is prob

-

ably more relevant to examine the relationship of

anaerobic infection and the inflammatory response in

the periodontal tissues to systemic disease (Fig. 16-12)

than to focus on clinical signs of periodontitis as has

been done in the epidemiological studies to date.

Thus, research workers in the future need to explore

how infection and inflammation in the periodontal

pocket may better explain the role of periodontitis as

a

risk for systemic disease.

Lastly, students of dentistry will ask, "if you treat

periodontitis, do you prevent the onset or reduce the

severity of systemic complications?" It is clear that

dentistry must now focus on intervention studies to

determine whether treating periodontitis will have a

beneficial effect on systemic diseases. This is not an

easy task and some studies will take considerable time

before we know the answer. However, there are excit

-

ing initial data which examine intervention and the

impact of periodontal treatment on preterm low birth

-

weight infants. In a preliminary study, Lamster and

his colleagues reported that periodontal intervention

decreased the risk of preterm low birthweight infants.

In a study of 195 young women at the School of

Pregnant and Parenting Teens in Central Harlem, the

overall prevalence of preterm low birthweight was

14.

6%. PLBW occurred in 18.8% of the women who

did

not receive periodontal intervention but in only

6.7%

of the women who received periodontal therapy

(

Mitchell-Lewis et al. 2000). Lopez and co-workers, in

a

noteworthy abstract, have recently reported that

periodontal therapy significantly reduces the risk of

preterm low birthweight in a study of 351 pregnant

women. The total incidence of PLBW in this cohort of

subjects was 6.26%. In women treated for periodonti

-

tis, the incidence of PLBW was only 1.84% while this

382 • CHAPTER

16

Fig. 16-10. Most studies to date

have used a clinical sign of perio-

dontitis such as probing depth to

relate periodontitis to systemic

complications.

Fig. 16-11. In addition to clinical

measures of disease severity, the

anaerobic bacterial burden and

the inflammatory response must

be taken into account in linking

periodontitis to systemic disease.

Fig. 16-12. Studying the anaerobic

bacterial burden and the inflam-

matory response may be more

critical than measures of pocket

depth in finding a relationship be-

tween periodontitis and systemic

complications.

incidence was 10.11% in untreated women. Lopez

concluded that periodontitis was an independent risk

factor for PLBW and that periodontal treatment sig-

nificantly reduced the risk of PLBW. These two studies

are compelling findings indeed and suggest that at

least

for preterm low birthweight babies, reducing

periodontal infection and disease can be very benefi

cial.

There are also studies being designed to look at

the

effect of intervention on cardiovascular disease.

Our

group, along with colleagues at Boston Univer

sity,

SUNY-Buffalo, University of Maryland and Ore

gon

Health Science University, have initiated plans for