Hugo W.B., Russel A.D.(ed). Pharmaceutical Microbiology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Another type of intrinsic resistance is shown by organisms that are capable of

producing constitutive enzymes which degrade biocide molecules. Heavy metal activity

is reduced by some strains of Sacch. cerevisiae which produce hydrogen sulphide;

this combines with heavy metals (e.g. copper, mercury) to form insoluble sulphides

thereby rendering the organisms less tolerant than non-enzyme-producing counterparts.

Inactivation of other fungitoxic agents has also been described, e.g. the role of formal-

dehyde dehydrogenase in resistance to formaldehyde and the degradation of potassium

sorbate by a Penicillium species. Degradation by fungi of biocides such as chlorhexidine,

QACs and other aldehydes does not appear to have been recorded.

2 Acquired resistance. This term is used to denote resistance arising as a consequence

of mutation or via the acquisition of genetic material. There is no evidence linking the

presence of plasmids in fungal cells and the ability of the organisms to acquire resistance

to fungicidal or fungistatic agents. The development of resistance to antiseptic-type

agents has not been widely studied, but acquired resistance to organic acids has been

demonstrated, presumably by mutation.

7 Sensitivity and resistance of protozoa

Several distinct types of protozoa (e.g. Giardia, Cryptosporidium, Naegleria, Entamoeba

and Acanthamoeba) are potentially pathogenic and may be acquired from water. A

resistant cyst stage is included in their life cycle, the trophozoite form being sensitive

to biocides. Little is known about mechanisms of inactivation by chemical agents and

there appear to have been few significant studies linking excystment and encystment

with the development of sensitivity and resistance, respectively.

From the evidence currently available, it is likely that the cyst cell wall acts in

some way as a permeability barrier, thereby conferring intrinsic resistance to the cyst

form.

8 Sensitivity and resistance of viruses

An important hypothesis was put forward in the USA by Klein and Deforest in 1963

and modified in 1983. Essentially the original concept was based on whether viruses

could be classified as:

1 'lipophilic', i.e. those, such as herpes simplex virus, which possessed a lipid

envelope; and

2 'hydrophilic', e.g. poliovirus, which did not contain a lipid envelope.

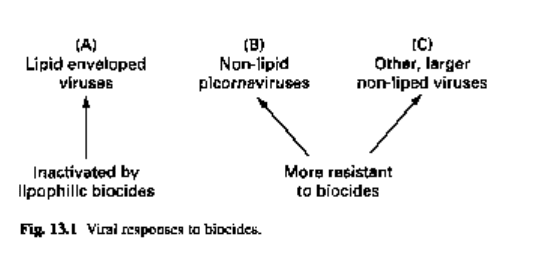

In the later (1983) modification, three groups were considered (Fig. 13.1):

1 lipid-enveloped viruses, which were inactivated by lipophilic biocides;

2 non-lipid picomaviruses (pico = very small, e.g. polio and Coxsackie viruses all of

which are RNA viruses);

3 other, larger, non-lipid viruses, e.g. adenoviruses.

Viruses in groups 2 and 3 are much more resistant to biocides.

Although many papers have been published on the virucidal (viricidal) activity of

biocides there is little information available about the uptake of biocides and their

penetration into viruses of different types, or of their interaction with viral protein and

nucleic acid.

Resistance to non-antibiotic antimicrobial agents 275

9 Activity of biocides against prions

Prions are responsible for the so-called 'slow virus diseases', a distinct group of

unusual neurological disorders. They are believed to be markedly resistant to

inactivation by many chemical and physical agents but because they have not been

purified, it is at present difficult to state whether this is an intrinsic property of prions

or whether it results from the protective effect of host tissue present. Certainly very

high concentrations of a biocide acting for long periods may be necessary to produce

inactivation.

10 Pharmaceutical and medical relevance

The inherent variability in biocidal sensitivity of microorganisms has several important

practical implications. For example, the population of bacteria making up the normal

flora of organisms contaminating the working surfaces, floor, air or water supply in an

environment such as a hospital pharmacy will probably contain a very low number of

naturally resistant organisms. These might be resistant to the agent used as a disinfectant

because they have acquired additional genetic information or lost, by mutation, genes

involved in controlling the expression of other genes. In the absence of the antimicrobial

agent, the resistant strains would have no competitive advantage over the sensitive

strains, and in fact they might grow more slowly and would not predominate in the

population. Under the selective pressure introduced by continual use of one kind of

disinfectant, resistant strains would predominate as the sensitive strains are eliminated.

Eventually the entire population would be resistant to the disinfectant and a serious

contamination hazard would arise. This fact is of significance in the design of suitable

hospital disinfection policies.

Tuberculosis is on the increase in developed countries such as the USA and

UK; furthermore, MAI may be associated with AIDS sufferers. Hospital-acquired

opportunistic mycobacteria may cause disseminated infection and also lung infections,

endocarditis and pericarditis. Transmission of mycobacterial infection by endoscopy

is rare, despite a marked increase in the use of flexible fibreoptic endoscopes, but

bronchoscopy is probably the greatest hazard for the transmission of M. tuberculosis

and other mycobacteria. Thus, biocides used for bronchoscope disinfection must be

chosen carefully to ensure that such transmission does not occur.

276 Chapter 13

11 Further reading

Bloomfield S.F. & Arthur M. (1994) Mechanisms of inactivation and resistance of spores to chemical

biocides. JAppl Bact Symp Suppl, 76, 91S-104S.

Brown M.R.W. & Gilbert P. (1993) Sensitivity of biofilms to antimicrobial agents. JAppl Bact Symp

Suppl, 74, 87S-97S.

Klein M. & Deforest A. (1983) Principles of viral inactivation. In: Disinfection, Sterilization and

Preservation (ed. S.S. Block), 3rd edn, pp. 422-434. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

Nikaido H., Kim S.-H. & Rosenberg E.Y. (1993) Physical organization of lipids in the cell wall of

Mycobacterium chelonae. Mol Microbiol, 8, 1025-1030.

Nikaido H. & Vaara M. (1985) Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol

Rev, 49, 1-32.

Russell A.D. (1995) Mechanisms of bacterial resistance to biocides. Int Biodet Biodeg, 36, 247-265.

Russell A.D. & Chopra I. (1996) Understanding Antibacterial Action and Resistance, 2nd edn.

Chichester: Ellis Horwood.

Russell A.D. & Day M.J. (1996) Antibiotic and biocide resistance in bacteria. Microbios, 85, 45-65.

Russell A.D. & Furr J.R. (1996) Biocides: mechanisms of antifungal action and fungal resistance. Sci

Progr, 79, 27-48.

Russell A.D. & Russell N.J. (1995) Biocides: activity, action and resistance. In: Fifty Years of

Antimicrobials: Past Perspectives and Future Trends (eds P.A. Hunter, G.K. Derby & NJ. Russell)

53rd Symposium of the Society for General Microbiology, pp. 327-365. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Russell A.D., Hugo W.B. & Ayliffe G.A.J, (eds) (1998) Principles and Practice of Disinfection,

Preservation and Sterilization, 3rd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Setlow P. (1994) Mechanisms which contribute to the long-term survival of spores of Bacillus species.

JAppl Bact Symp Suppl, 76, 49S-60S.

Stickler D.J. & King J.B. (1998) Intrinsic resistance to non-antibiotic antibacterial agents. In: Principles

and Practice of Disinfection, Preservation and Sterilisation (eds A.D. Russell, W.B. Hugo & G.A.J.

Ayliffe), 3rd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Taylor D.M. (1998) Inactivation of unconventional agents of the transmissible degenerative

encephalopathies. In: Principles and Practice of Disinfection, Preservation and Sterilization (eds

A.D. Russell, W.B. Hugo & G.A.J. Ayliffe), 3rd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Resistance to non-antibiotic antimicrobial agents 277

Fundamentals of immunology

Introduction

The science of immunology is one of the most rapidly expanding sciences and represents

a vast area of knowledge and research; thus, in a short chapter it is impossible to deal in

depth with its theory and application and a list of further reading is given at the end of

the chapter.

Historical aspects of immunology

From almost the first written observations by man it was recognized that persons who

had contracted and recovered from certain diseases were not susceptible (i.e. were

immune) to further attacks. Thucydides, over 2500 years ago, described in detail an

1 Introduction 4.5.2 The alternative pathway

1.1 Historical aspects of immunology 4.5.3 Regulation of complement activity

1.2 Definitions 4.6 Cell-mediated immunity (CMI)

4.6.1 Helper T cells (TH cells)

2 Non-specific defence mechanisms 4.6.2 Suppressor T cells (Ts cells)

(innate immune system) 4.6.3 Cytotoxic T cells (Tc cells)

2.1 Skin and mucous membranes 4.7 Immunoregulation

2.2 Phagocytosis 4.8 Natural killer (NK) cells

2.2.1 Role of phagocytosis 4.9 Immunological tolerance

2.3 The complement system and other 4.10 Autoimmunity

soluble factors

2.4 Inflammation 5 Hypersensitivity

2.5 Host damage 5.1 Type I (anaphylactic) reactions

2.5.1 Exotoxins 5.2 Type II (cytolytic or cytotoxic) reactions

2.5.2 Endotoxins 5.3 Type III (complex-mediated) reactions

5.4 Type IV (delayed hypersensitivity)

3 Specific defence mechanisms (adaptive reactions

immune system) 5.5 Type V (stimulatory hypersensitivity)

3.1 Antigenic structure of the microbial cell reactions

4 Cells involved in immunity 6 Tissue transplantation

4.1 Humoral immunity 6.1 Immune response to tumours

4.2 Monoclonal antibodies

4.2.1 Uses of monoclonal antibodies 7 Immunity

4.3 Immunoglobulin classes 7.1 Natural immunity

4.3.1 Immunoglobulin M (IgM) 7.1.1 Species immunity

4.3.2 Immunoglobulin G (IgG) 7.1.2 Individual immunity

4.3.3 Immunoglobulin A (IgA) 7.2 Acquired immunity

4.3.4 Immunoglobulin D (IgD) 7.2.1 Active acquired immunity

4.3.5 Immunoglobulin E (IgE) 7.2.2 Passive acquired immunity

4.4 Humoral antigen-antibody reactions

4.5 Complement 8 Further reading

4.5.1 The classical pathway

14

epidemic in Athens (which could have been typhus or plague) and noted that sufferers

were 'touched by the pitying care of those who had recovered because they were

themselves free of apprehension, for no-one was ever attacked a second time or with a

fatal result'.

Many attempts were made to induce this immune state. In ancient times the process

of variolation (the inoculation of live organisms of smallpox obtained from diseased

pustules from patients who were recovering from the disease) was practised extensively

in India and China. The success rate was very variable and often depended on the skill

of the variolator. The results were sometimes disastrous for the recipient. The father of

immunology was Edward Jenner, an English country doctor who lived from 1749 to

1823. He had observed on his rounds the similarity between the pustules of smallpox

and those of cowpox, a disease that affected cows' udders. He also observed that

milkmaids who had contracted cowpox by handling the diseased udders were immune

to smallpox. Deliberate inoculation of a young boy with cowpox and a later subsequent

challenge, after the boy had recovered, with the contents of a pustule taken from a

person who was suffering from smallpox failed to induce the disease and subsequent

rechallenges also failed. The process of vaccination (Latin, vacca, cow) was adopted

as a preventative measure against smallpox, even though the mechanism by which this

immunity was induced was not understood.

In 1801, Jenner prophesied the eradication of smallpox by the practice of vaccination.

In 1967 the disease infected 10 million people. The World Health Organization (WHO)

initiated a programme of confinement and vaccination with the object of eradicating

the disease. In Somalia in 1977 the last case of naturally acquired smallpox occurred,

and in 1979 the WHO announced the total eradication of smallpox, thus fulfilling

Jenner's prophecy.

The science of immunology not only encompasses the body's immune responses

to bacteria and viruses but is extensively involved in: tumour recognition and subsequent

rejection; the rejection of transplanted organs and tissues; the elimination of parasites

from the body; allergies; and autoimmunity (the condition when the body mounts a

reaction against its own tissues).

1.2 Definitions

Disease in humans and animals may be caused by a variety of microorganisms, the

three most important groups being bacteria, rickettsia and viruses.

An organism which has the ability to cause disease is termed a. pathogen. The term

virulence is used to indicate the degree of pathogenicity of a given strain of

microorganism. Reduction in the normal virulence of a pathogen is termed attenuation;

this can eventually result in the organism losing its virulence completely and it is then

termed avirulent. Conversely, any increase in virulence is termed exaltation.

The body possesses an efficient natural defence mechanism which restricts

microorganisms to areas where they can be tolerated. A breach of this mechanism,

allowing them to reach tissues which are normally inaccessible, results in an infection.

Invasion and multiplication of the organism in the infected host may result in a

pathological condition, the clinical entity of disease.

Fundamentals of immunology 279

2

Non-specific defence mechanisms (innate immune system)

The body possesses a number of non-specific antimicrobial systems which are operative

at all times against potentially pathogenic microorganisms. Prior contact with the

infectious agent has no intrinsic effect on these systems.

2.1 Skin and mucous membranes

The intact skin is virtually impregnable to microorganisms and only when damage

occurs can invasion take place. Furthermore, many microorganisms fail to survive on

the skin surface for any length of time due to the inhibitory effects of fatty acids and

lactic acid in sweat and sebaceous secretions. Mucus, secreted by the membranes lining

the inner surfaces of the body, acts as a protective barrier by trapping microorganisms

and other foreign particles and these are subsequently removed by ciliary action linked,

in the case of the respiratory tract, with coughing and sneezing.

Many body secretions contain substances that exert a bactericidal action, for example

the enzyme lysozyme which is found in tears, nasal secretions and saliva; hydrochloric

acid in the stomach which results in a low pH; and basic polypeptides such as spermine

which are found in semen.

The body possesses a normal bacterial flora which, by competing for essential

nutrients or by the production of inhibitory substances such as monolactams or colicins,

suppresses the growth of many potential pathogens.

2.2 Phagocytosis

Metchnikoff (1883) recognized the role of cell types (phagocytes) which were

responsible for the engulfment and digestion of microorganisms. They are a major line

of defence against microbes that breach the initial barriers described above. Two types

of phagocytic cells are found in the blood, both of which are derived from the totipotent

bone marrow stem cell.

1 The monocytes, which constitute about 5% of the total blood leucocytes. They

migrate into the tissues and mature into macrophages (see below).

2 The neutrophils (also called polymorphonuclear leucocytes, PMNs), which are the

professional phagocytes of the body. They constitute >70% of the total leucocyte

population, remaining in the circulatory system for less than 48 hours before migrating

into the tissues, in response to a suitable stimulus, where they phagocytose material.

They possess receptors for Fc and activated C3 which enhance their phagocytic ability

(see later in chapter).

Another group of phagocytic cells are the macrophages. These are large, long-

lived cells found in most tissues and lining serous cavities and the lung. Other

macrophages recirculate through the secondary lymphoid organs, spleen and lymph

nodes where they are advantageously placed to filter out foreign material. The total

body pool of macrophages constitutes the so-called reticuloendothelial system (RES).

Macrophages are also involved with the presentation of antigen to the appropriate

lymphocyte population (see later).

280 Chapter 14

Role of phagocytosis

The microorganism initially adheres to the surface of the phagocytic cell, and this is

then followed by engulfment of the particle so that it lies within a vacuole (phagosome)

within the cell. Lysosomal granules within the phagocyte fuse with the vacuole to form

a phagolysosome. These granules contain a variety of bactericidal components which

destroy the ingested microorganism by systems that are oxygen-dependent or oxygen-

independent.

When a microorganism breaches the initial barriers and enters the body tissues, the

phagocytes form a formidable defence barrier. Phagocytosis is greatly enhanced by a

family of proteins called complement.

The complement system and other soluble factors

Complement comprises a group of heat-labile serum proteins which, when activated,

are associated with the destruction of bacteria in the body in a variety of ways. It is

present in low concentrations in serum but, as its action is linked intimately with a

second (specific) set of defence mechanisms, its composition and role will be dealt

with later in the chapter.

Proteins produced by virally infected cells have been shown to interfere with viral

replication. They also activate leucocytes that can recognize these infected cells and

subsequently kill them. These leucocytes are known as natural killer (NK) cells and the

proteins are termed interferons (see also Chapters 3, 5 and 24).

The serum concentration of a number of proteins increases dramatically during

infection. Their levels can increase by up to 100-fold compared with normal levels.

They are known collectively as acute phase proteins and certain of them have been

shown to enhance phagocytosis in conjunction with complement.

Inflammation

One early symptom of injury to tissue due to a microbial infection is inflammation.

This begins with the dilatation of local arterioles and capillaries which increases the

blood flow to the area and causes characteristic reddening. Fluid accumulates in the

area of the injury due to an increase in the permeability of the capillary walls and this

leads to localized oedema, which creates a pressure on nerve endings resulting in pain.

This early oedema may actually promote bacterial growth. Fibrin is deposited which

tends to limit the spread of the microorganisms. Blood phagocytes adhere to the inside

of the capillary walls and penetrate through into the surrounding tissue. They are attracted

to the focus of the infection by chemotactic substances in the inflammatory exudate

originating from complement.

Inflammation is a non-specific reaction which can be induced by a variety of

agents apart from microorganisms. Lymphokines and derivatives of arachidonic acid,

including prostaglandins, leukotrienes and thromboxanes are probable mediators of

the inflammatory response. The release of vasoactive amines such as histamine and

serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) from activated or damaged cells also contribute to

inflammation.

Fundamentals of immunology 281

Fever is the most common manifestation. The thermoregulatory centre in the

hypothalamus regulates body temperature and this can be affected by endotoxins

(heat-stable lipopolysaccharides) of Gram-negative bacteria and also by a monokine

secreted by monocytes and macrophages called interleukin-1 (IL-1) which is also

termed endogenous pyrogen. Antibody production and T-cell proliferation have been

shown to be enhanced at elevated body temperatures and thus are beneficial effects of

fever.

2.5 Host damage

Microorganisms that escape phagocytosis in a local lesion may now be transported to

the regional lymph nodes via the lymphatic vessels. If massive invasion occurs with

which the resident macrophages are unable to cope, microorganisms may be transported

through the thoracic duct into the bloodstream. The appearance of viable microorganisms

in the bloodstream is termed bacteraemia and is indicative of an invasive infection and

failure of the primary defences.

Pathogenic organisms possess certain properties which enable them to overcome

these primary defences. They produce metabolic substances, often enzymic in nature,

which facilitate the invasion of the body. The following are examples of these.

1 Hyaluronidase and streptokinase are produced by the haemolytic streptococci and

enable the organism to spread rapidly through the tissue. Hyaluronidase dissolves

hyaluronic acid (intercellular cement), whereas streptokinase (Chapter 25) dissolves

blood clots.

2 Coagulase is produced by many strains of staphylococci and causes the coagulation

of plasma surrounding the organism. This can act as a barrier protecting the organism

against phagocytosis. The presence of a capsule outside the cell wall serves a similar

function. The production of coagulase (Chapter 1) is used as an indication of the

pathogenicity of the strain.

3 Lecithinase is produced by Clostridium perfringens. This is a calcium-dependent

lecithinase whose activity depends on the ability to split lecithin. Since lecithin is present

in the membrane of many different kinds of cells, damage can occur throughout the

body. Lecithinase causes the hydrolysis of erythrocytes and the necrosis of other tissue

cells.

4 Collagenase is also produced by CI. perfringens and this degrades collagen, which

is the major protein of fibrous tissue. Its destruction promotes the spread of infection in

tissues.

5 Leucocidins kill leucocytes and are produced by many strains of streptococci, most

strains of Staphylococcus aureus and likewise most strains of pathogenic Gram-negative

bacteria, isolated from sites of infection.

Damage to the host may arise in two ways. First, multiplication of the micro-

organisms may cause mechanical damage to the tissue cells through interference with

the normal cell metabolism, as seen in viral and some bacterial infections. Second, a

toxin associated with the microorganism may adversely affect the tissues or organs of

the host. Two types of toxins, called exotoxins and endotoxins, are associated with

bacteria.

282 Chapter 14

2.5.1

Exotoxins

These are produced inside the cell and diffuse out into the surrounding environment.

They are produced by both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. They are

extremely toxic and are responsible for the serious effects of certain diseases; for

example, the toxin produced by CI. tetani (the causal organism of tetanus) is neurotoxic

and causes severe muscular spasms due to impairment of neural control. Examples of

other toxins identified are necrotoxins (causing tissue damage), enterotoxins (causing

intestinal damage) and haemolysins (causing haemolysis of erythrocytes). Gram-positive

bacteria producing exotoxins are certain members of the genera Clostridium,

Streptococcus and Staphylococcus whilst an example of a Gram-negative bacterium is

Vibrio cholerae (the causal organism of cholera). Several exotoxins consist of two

moieties: one aids entrance of the exotoxin into the target cell whilst the toxic activity

is associated with the other fraction.

2.5.2 Endotoxins

These are lipopolysaccharide-protein complexes associated mainly with the cell

envelope of Gram-negative bacteria (see Chapter 1). They are responsible for the general

non-specific toxic and pyrogenic reactions (Chapters 1 and 18) common to all organisms

in this group. The specific toxic reactions for different pathogenic Gram-negative

bacteria are due to the production of a toxin in vivo. Organisms of interest in this group

are those causing cholera, plague, typhoid and paratyphoid fever, and whooping-cough.

3 Specific defence mechanisms (adaptive immune system)

Microorganisms which successfully overcome the non-specific defence mechanisms

then have to contend with a second line of defence, the specific defence mechanisms.

These involve the stimulation of a specific immune response by the invading

microorganism and are evoked by what are termed immunogens. These may cause

the appearance in the serum of modified serum globulins called immunoglobulins.

The term antigen is given to a substance that stimulates immunoglobulins that have

the ability to combine with the antigen that stimulated their production. These

immunoglobulins are then termed antibodies. All antibodies are immunoglobulins but

it is not certain that all immunoglobulins have antibody function. Antigens associated

with microorganisms consist of proteins, polysaccharides, lipids or mixtures of the

three and invariably have a high molecular weight. The antigen-antibody reaction is a

highly specific one and this specificity is due to differences in the chemical composition

of the outer surfaces of the organism. Bacteria, rickettsia and viruses all have the ability

to induce antibody formation. The synthesis and release of free antibody into the blood

and other body fluid is termed the humoral immune response.

Antigens, however, can induce a second type of response which is known as the

cell-mediated immune response. The antigenic agent stimulates the appearance of

'sensitized' lymphocytes in the body which confer protection against organisms that

have the ability to live and replicate inside the cells of the host. Certain of these

lymphocytes are also involved in the rejection of tissue grafts.

Fundamentals of immunology 283

3.1

Antigenic structure of the microbial cell

The microbial cell surface constitutes a multiplicity of different antigens. These antigens

may be common to different species or types of microorganisms or may be highly

specific for that one type only.

Three groups of antigens are found in the intact bacterial cell.

H-antigens. These are associated with the flagella and are therefore only found

on motile bacteria (H, Hauch, a film, and refers to the film-like swarming seen

originally in cultures of flagellated Proteus). The precise chemical composition of

flagella can vary between bacteria, resulting in a range of different antibodies being

produced and use is made of these differences in the typing of different strains of

Salmonella.

O-antigens. These are associated with the surface of the bacterial cell wall and are

often referred to as the somatic antigens (O, ohne Hauch, without film, and refers to

non-swarming cultures, i.e. absence of flagella). The specificity of the reaction between

these antigens and the corresponding antibodies in Gram-negative bacteria is due to

the nature and number of the type-specific polysaccharide side-chains attached to the

lipid A and core polysaccharide portion of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (see Chapter

1). This group of organisms is, however, very liable to mutate during cultivation in

artificial media and the resultant mutant may lose the O-specific side-chain antigens,

resulting in the exposure of the more deep-seated core polysaccharide, the R (rough)

antigens, which may share a common structure with other unrelated Gram-negative

bacteria and so are no longer type-specific. This change is known as the S —> R change

and is so called because of an alteration in the appearance of the colonies of the organism

from the normal, smooth, glistening colony to a rough-edged, matt colony. This S —> R

change represents a loss of the type-specific O-antigens with a concomitant loss in the

specificity of the antigen-antibody reaction.

The major type-specific antigens of Gram-positive bacteria are the teichoic acid

moieties associated with the cell wall (see Chapter 1).

Surface antigens. Many bacteria possess a characteristic polysaccharide capsule external

to the cell wall and this too has antigenic properties. Over 80 serological types of the

Gram-positive Pneumococcus group have been differentiated by immunologically

distinct polysaccharides in the capsule. Certain Gram-negative organisms of the enteric

bacteria, e.g. salmonellae, may possess a polysaccharide microcapsule which is also

antigenic and is thought to be responsible for the virulence of the bacteria. It is termed

the Vi antigen and its presence is important in relation to the production of the typhoid

vaccines.

4 Cells involved in immunity

The cells that make up the immune system are distributed throughout the body but are

found mainly in the lymphoreticular organs, which may be divided into the primary

lymphoid organs, i.e. the thymus and bone marrow, and the secondary or peripheral

284 Chapter 14