Holford Matthew, Stringer Keith. Border Liberties and Loyalties in North-East England, 1200-1400 (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BORDER LIBERTIES AND LOYALTIES

166

On 10 February 1303, a er the community of the liberty had provided

men- at- arms and foot- soldiers to ght at the king’s wages, Edward wrote

to reassure it that such service would not be used as a harmful precedent,

and he repeated his assurance on 19 April.

143

In 1311 the local community

reiterated (apparently with success) the claim that service beyond Tyne or

Tees would be to ‘the damage of the liberty of St Cuthbert’, and the privilege

was repeatedly recon rmed.

144

So the liberty was o en asked to perform

military service; but it was usually acknowledged that such service was

being provided freely, and could not be exacted. Arguably, in the long run,

the claim established in 1300–3 was successful.

145

e question of military service, in May and (perhaps) February 1303,

had been among the disputed issues reserved for consideration in a future

session of Parliament.

146

In the end, however, events overtook any such

plans: no Parliament was held between October 1302 and February 1305,

and by the latter date further proceedings were being brought against

Bek, leading to another con scation of the liberty in December 1305.

Nevertheless Edward I’s gesture towards wider political consultation is

important. Decisions relating to the governance and customs of a liberty

as signi cant as Durham were not to be taken lightly. Edward showed no

such circumspection when the liberty of Tynemouthshire was con scated

between 1291 and 1299.

147

In general, the king’s attitude to the liberty during the dispute showed

more caution than might be expected. Historical consensus holds that

while Edward I took very seriously his duty to answer complaints from the

inhabitants of liberties, he had no objection to ‘franchises’ provided that

his overall control was recognised.

148

Edward’s respect for Durham was

rather greater than such an assessment suggests, even if the con scations

of the liberty le no doubt about the king’s ultimate mastery. As we have

noted elsewhere, he scrupulously maintained the independent functioning

of the liberty while it was under his control.

149

More striking, however, is

143

DCM, 2.2.Reg.12; CPR 1301–7, pp. 112, 134 (but cf. p. 426).

144

DCM, Loc.XXVIII.14, no. 15; Surtees, I, i, Appendix, no. 16 (printing DCM, 1.4.Reg.2).

145

Above, Chapter 1, pp. 42–3. Requests for military service from the liberty before 1327

are usefully listed in the digests in Parl. Writs, I; II, iii; see also RPD, i, pp. 16–17; ii, pp.

989–90, 1003–4, 1100–1. Examples of the reservation of the liberty’s privileges include

RPD, i, pp. 16–17; iv, pp. 512–13; Rot. Scot., i, pp. 169, 196; CPR 1321–4, p. 191; 1330–4,

p. 460; 1340–3, p. 348; C 81/280/14468.

146

RPD, iii, p. 46; CPR 1301–7, p. 149; above, p. 163, n. 133.

147

Below, Chapter 5, pp. 207, 219.

148

See, for example, Select Cases in the Court of King’s Bench, ed. G. O. Sayles (Selden Society,

1936–71), ii, p. lv; Prestwich, Edward I, pp. 258–64, 538–40; Davies, Lordship and Society,

pp. 257–69.

149

Above, Chapter 2, pp. 66–7, 75.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 166M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 166 4/3/10 16:12:554/3/10 16:12:55

DURHAM UNDER BISHOP ANTHONY BEK

167

Edward’s acknowledgement of the bishop’s prerogative wardship, all the

more so because the king was actively de ning and not simply con rm-

ing this privilege. No less remarkable was his respect for the community’s

exemption from military service. Both cases illustrate the arguments put

forward in an earlier chapter about the crown’s attitude to the liberty. e

power of Cuthbert, the liberty’s patronal saint, certainly encouraged Edward

to treat Durham with great circumspection: in the king’s own words, he

was simply the ‘minister and maintainer of the liberty of St Cuthbert’.

150

Furthermore, the privileges of wardship and exemption from military

service were both strongly associated with the liberty ‘between Tyne and

Tees’: the Haliwerfolk positioned themselves within the two rivers, and it

was similarly there that, according to Prerogativa Regis and other sources,

the bishop exercised his rights of prerogative wardship. As has been seen,

the distinctive status of the lands and people ‘between Tyne and Tees’ was

rmly established, well supported by powerful cultural and historical tradi-

tions.

151

It was these cultural and historical traditions, claimed as they were

by both bishop and local community, that ultimately enabled both parties

not only to retain, but to con rm and increase their privileges – privileges

that were not always compatible.

e dispute between Bek and his tenants, as we have seen, has some

parallels in the con ict between Bishop Langley and his tenants in 1433.

It also has analogues in various other liberties where the exploitation of

lordship led to collective resistance and, in some cases, to royal interven-

tion and to ‘charters of liberties’.

152

e Bek dispute, admittedly, allows

both collective activity and royal intervention to be followed in unusual

detail. But it was also distinctive in more signi cant ways, which re ected

the factors that made Durham unique among the north- eastern liberties.

Important above all was the historical culture explored in Chapter 1,

which lay behind many of the features that distinguished the ‘revolt’ of

1300–3 from that of 1433. e outbreak of opposition to Bek was made

possible because the protection and privileges St Cuthbert bestowed on

the liberty were claimed by the local community and by Durham Priory,

as well as by the bishop himself. A sense of traditional rights and freedoms

facilitated the emergence of collective action. e resolution of the dispute

by Edward I, similarly, re ected the king’s respect for the claims of these

various parties.

150

Above, Chapter 1, p. 37; C. M. Fraser, ‘Edward I of England and the regalian franchise of

Durham’, Speculum, 31 (1956), pp. 329, 336, 338, 342.

151

Above, Chapter 1, especially pp. 44–52.

152

Below, Conclusions, p. 428.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 167M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 167 4/3/10 16:12:554/3/10 16:12:55

BORDER LIBERTIES AND LOYALTIES

168

One e ect of the dispute was to cement the rights of these di erent

constituencies in the liberty. In extensive extracts from royal records and

other sources, the priory recorded its victories over the bishop and his

ministers.

153

King John’s charter to the Haliwerfolk of 1208 was copied

by the priory, and became newly important as a record of local privilege.

e Haliwerfolk themselves gained a new self- identi cation in the years

around 1300, and the dispute provided a crucial stimulus to the develop-

ment of collective action and institutions in the liberty, as ‘the community

of the liberty’ made its rst sustained appearance. One lasting result of the

dispute was that the rights of these constituencies became more clearly

de ned. Bek’s ‘charter of liberties’, which was also in places a royal a rma-

tion of the bishop’s own ‘liberties’, became something like an authoritative

statement.

154

On a broader view, what impact did the dispute have on the liberty’s

development in the longer term? Most profoundly, the shape and integrity

of the bishopric were fundamentally a ected by Edward I’s con scation

of Barnard Castle and Hartness when the liberty was in royal hands in

1306–7. It marked not only a theoretical challenge to the bishops’ powers

of prerogative, but a signi cant decrease in their in uence in the wapen-

take of Sadberge: Bishop Poore’s victories over Peter Bruce in Hartness

were considerably undermined a er its grant to the Cli ords. is sup-

ports the judgement that the liberty’s privileges were diminished by the

dispute. Such was the opinion of the Durham priory chronicler, writing a

little later, and his verdict – as well as being echoed by Lapsley and other

historians

155

– appears to have been shared by some contemporaries. Even

in the immediate a ermath of the dispute it may have seemed that, despite

Edward I’s scrupulous preservation of the liberty’s privileges in 1302–3, its

status was not secure. In March 1304, several months a er the liberty had

been restored to Bek, Peter Tursdale and Agnes his wife quitclaimed to

Durham Priory their common land in Ferryhill and the Merringtons. At

the same time, they agreed – if they should be so required – to levy a nal

concord before the bishop’s justices, ‘or before the justices of the king of

153

See in particular DCM, Loc.VII, passim.

154

Thus in DCM, 1.5.Pont.3, art. 12, of c. 1400, it is implied that the charter offered a defini-

tive ruling on prerogative wardship – although doubt was cast on whether this should

bind Durham Priory, which had not been party to the charter. Cf. Richardson, ‘Bek’, p.

193, n. 21.

155

Scriptores Tres, pp. 88–9; Lapsley, Durham, p. 42; J. W. Alexander, ‘The English palati-

nates and Edward I’, JBS, 22 (1983), p. 10. The re- establishment of Bek’s authority over

the liberty following its restoration in 1307 is examined in detail in Fraser, Bek, pp.

215–28.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 168M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 168 4/3/10 16:12:554/3/10 16:12:55

DURHAM UNDER BISHOP ANTHONY BEK

169

England if they should happen for any reason to hold pleas in the liberty of

Durham’.

156

e possibility of royal interference in the liberty was real; and it also

remained real because of the circumstances in which the dispute of 1300–3

had been resolved. Edward I assumed responsibilities which went beyond

the usual royal duty of doing justice to all subjects. When the liberty was

restored in July 1303 Edward threatened royal intervention if the ‘charter

of liberties’ was not observed; the charter itself was copied onto the close

roll in the royal chancery, and the original was given to William Green eld,

the king’s chancellor, for safe- keeping. When the bishop was later accused

of failing to honour the settlement, the community was forced to petition

Edward for the return of the original charter.

157

e local community thus

developed a habit of turning directly to the crown, and complaints against

the bishop continued to be made. Early in 1307 – while the liberty was in

royal hands – ‘the community’ complained in Parliament about the exac-

tions of the bishop’s o cers; and it did so again later the same year.

158

e

liberty’s direct relationship with the crown persisted in some sense until

1353. In this year, when ‘the community of the bishopric’ (for reasons that

are unclear) sought an exempli cation of Bek’s charter, it did not turn to

the current bishop, omas Hat eld, but to Edward III, who inspected and

con rmed the text on the royal close roll.

159

It must be emphasised that the liberty was returned, shortly a er Edward

II’s accession in 1307, with the privileges of the bishops of Durham largely

untouched, and in some ways even strengthened. Nevertheless Edward

I’s role in con rming these privileges does deserve emphasis, because the

dispute was a foretaste of the increasingly important role the crown was

to play in de ning the liberty. And by reviewing that growing role, we can

draw to a close the story of the dispute, and highlight the wider motifs

in the liberty’s later history that have emerged in the preceding chapters.

e scal and military demands of successive kings, and the increasingly

antiquated nature of the liberty’s legal system, all made negotiation with

the crown ever more necessary in the rst half of the fourteenth century.

Bishops of Durham were increasingly driven to petition kings of England

for clari cation or con rmation of their privileges, or to limit the activities

156

DCM, 4.12.Spec.13, 14.

157

PROME, ii, p. 106 (and cf. p. 194). For earlier events, see Fraser, Bek, pp. 190, 192–6. It

was perhaps the original charter, rather than the close roll text, which formed the basis of

two copies made at Durham in the early fourteenth century: BL, MS Lansdowne 397, ff.

266r–8r; RPD, iii, pp. 61–7.

158

Northern Pets, no. 179.

159

DCM, 2.4.Pont.13.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 169M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 169 4/3/10 16:12:554/3/10 16:12:55

BORDER LIBERTIES AND LOYALTIES

170

of royal o cials. It was thus apparently with the assent of Edward III and

Parliament that the liberty’s legal system was reformed around the 1340s.

160

But the growing role of the crown, and indeed of Parliament, in the de ni-

tion of the liberty by no means led to its diminution. e commons did

attack some of Durham’s privileges – notably, in the 1370s, its immunity

from taxation – but the overwhelming trend of parliamentary legislation

in the later fourteenth and the eenth centuries was to con rm and even

extend the liberty’s rights.

161

e Bek dispute also presaged the growing informal in uence of

the crown in the liberty’s social and political life. e development of the

dispute in 1300–1 owed something to personal links between Edward

I and the liberty’s magnates, especially John Fitzmarmaduke; and, not

surprisingly, the dispute strengthened their associations with the crown.

Fitzmarmaduke le for Scotland, where he had been in the king’s service at

intervals since 1301; by 1309 he was governor of Perth, and in 1310 Edward

II rewarded him for his services with lands worth £200 a year. Indeed he

was to die in Perth, although he did request burial in the bishopric.

162

Nor

was Fitzmarmaduke the only one to imagine that his best opportunities

lay outside the liberty, or who wished to keep a low pro le until the end of

Bek’s episcopate. Alan Teesdale, another representative of the local com-

munity, pursued a career in the service of Hugh Despenser the younger

and of Edward II, probably because he faced reprisals from Bek a er the

restoration of the liberty.

163

As we have seen, the growth of the crown’s indirect in uence within

the bishopric did not lead automatically to an undermining of the liberty’s

autonomy.

164

But it did mark a real change in the later medieval history of

the bishopric – in summary, ‘the growing importance of Westminster’.

165

is was something Durham shared with the other north- eastern liberties,

largely as a result of war with Scotland. In other ways, however, Durham

was distinctive. What Jean Scammell called ‘the static infertility of fran-

chise’ is far from universally evident in the North- East: witness the develop-

ment of justices of the peace in Hexhamshire and Tynemouthshire, as well

160

Above, Chapter 2, pp. 73, 81.

161

C. D. Liddy, ‘The politics of privilege: Thomas Hatfield and the palatinate of Durham,

1345–81’, Fourteenth Century England, 4 (2006), pp. 71–5; T. Thornton, ‘Fifteenth-

century Durham and the problem of provincial liberties in England and the wider ter-

ritories of the English crown’, TRHS, 6th ser., 11 (2001), p. 94.

162

CDS, v, nos. 2300, 2406, 2424, 2436, 2452, 2460, 2716, 2745; CCR 1307–13, pp. 182–3;

CPR 1307–13, pp. 226, 228; RPD, ii, pp. 1149–50; Fraser, Bek, pp. 104, 218, n. 1.

163

Fraser, Bek, p. 217; above, Chapter 3, p. 132.

164

Above, Chapter 3, pp. 134–5.

165

Liddy, ‘Politics of privilege’, p. 79.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 170M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 170 4/3/10 16:12:554/3/10 16:12:55

DURHAM UNDER BISHOP ANTHONY BEK

171

as in Durham itself.

166

But no other north- eastern liberty developed a er

the mid- fourteenth century in quite the same way as Durham. e liberty’s

administration was increasingly modelled on Westminster; men associated

with the royal courts played a greater role in the liberty’s courts, and the

liberty increasingly came to resemble royal government in miniature. At

the same time, and as a result, the bishops’ regalian jurisdiction became

increasingly elaborate, as was symbolised by Bishop Hat eld’s ostentatious

seal, directly modelled on the royal great seal.

167

Contrary to the arguments

of some earlier writers, it may well have been the century and a half a er

1345, and not the years around 1300, that marked the liberty’s greatest

development.

What this meant for the inhabitants of the liberty is not always clear. But

it is perhaps signi cant that it was the mid- 1340s – years of dramatic reform

in the liberty – that witnessed the refusal of the Haliwerfolk to carry out an

inquisition post mortem for royal commissioners.

168

Durham’s institutional

development may well have strengthened its inhabitants’ identi cation

with the liberty. Loyalties, of course, were complex, and could not always

be relied on, as Bishop Langley found to his cost in 1433.

169

But in general,

as Tim ornton in particular has shown, the liberty seems to have our-

ished in the eenth century.

170

is was in part the result of institutional

evolution in the liberty, which continued to keep pace with developments

in royal government such as the expansion of equity jurisdiction. It also,

perhaps, owed something to the vigorous defences of the bishopric’s privi-

leges mounted at Durham Priory. But we must not neglect the actions and

loyalties of the liberty’s inhabitants: ‘the people called Haliwerfolk’, as they

could still be described.

171

166

Scammell, ‘Origin and limitations’, p. 463; below, Chapter 5, pp. 193, 227.

167

Above, Chapter 2, p. 65.

168

Above, Chapter 1, pp. 51–2.

169

Storey, Langley, pp. 116–34.

170

Thornton, ‘Fifteenth- century Durham’, passim.

171

DCM, Cart. III, f. 1r.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 171M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 171 4/3/10 16:12:554/3/10 16:12:55

172

5

Hexhamshire and Tynemouthshire

Matthew Holford

I

n many respects the liberties of Hexhamshire and Tynemouthshire, held

respectively by the archbishop of York and the prior of Tynemouth, had

little in common. They were of contrasting geographical character, for

Hexhamshire was compact and Tynemouthshire dispersed. Hexhamshire’s

privileges were substantial and well established; Tynemouthshire’s rights,

on the other hand, especially from around the 1290s to the 1330s, faced

serious challenges from the crown and from the priory’s own tenants.

The lordship of the absentee archbishops of York was rarely oppressive or

resented, whereas successive priors of Tynemouth alienated many of their

more substantial tenants. The contrasts are great: but it is these contrasts

that justify analysis of the two liberties together. Above all, their divergent

stories show clearly how the impact of liberties on local society was deter-

mined by the complex interactions of lordship and jurisdictional privilege.

e outlines of these stories are not new, as both liberties have been

given considerably more scholarly attention than Tynedale or Redesdale.

Both – and Tynemouthshire in particular – received valuable coverage

in the Northumberland County History.

1

No apology, though, need be

made for a reconsideration of lordship and loyalties in both liberties that

draws on the full range of available evidence. And while neither liberty

is as well documented as Durham, each has its particular archival riches.

For Hexhamshire the key sources are the registers and cartularies of the

archbishops of York, although these vary considerably in the amount of

relevant material they contain. Unusually rich for the rst half of the thir-

teenth century, they provide a steady record of o cial appointments and

business from the late thirteenth until the mid- fourteenth century, when

entries concerning the liberty become much scarcer. For Tynemouthshire

the principal source is the register or cartulary compiled mostly under Prior

Robert Tewing (1315–40). is includes a wide range of material relating to

1

NCH, iii (by A. B. Hinds), and iv (by J. C. Hodgson); viii and ix (by H. H. E. Craster).

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 172M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 172 4/3/10 16:12:564/3/10 16:12:56

HEXHAMSHIRE AND TYNEMOUTHSHIRE

173

the liberty, particularly for the period between around 1290 and 1340: not

only formal grants and deeds, but manorial surveys, legal extracts, other

memoranda, and records of leases. Again, however, the sources become

relatively few a er the mid- fourteenth century. For both liberties, therefore,

the period to around 1350 lends itself to particularly detailed coverage; and

this period provides the focus of the following discussions.

Hexhamshire

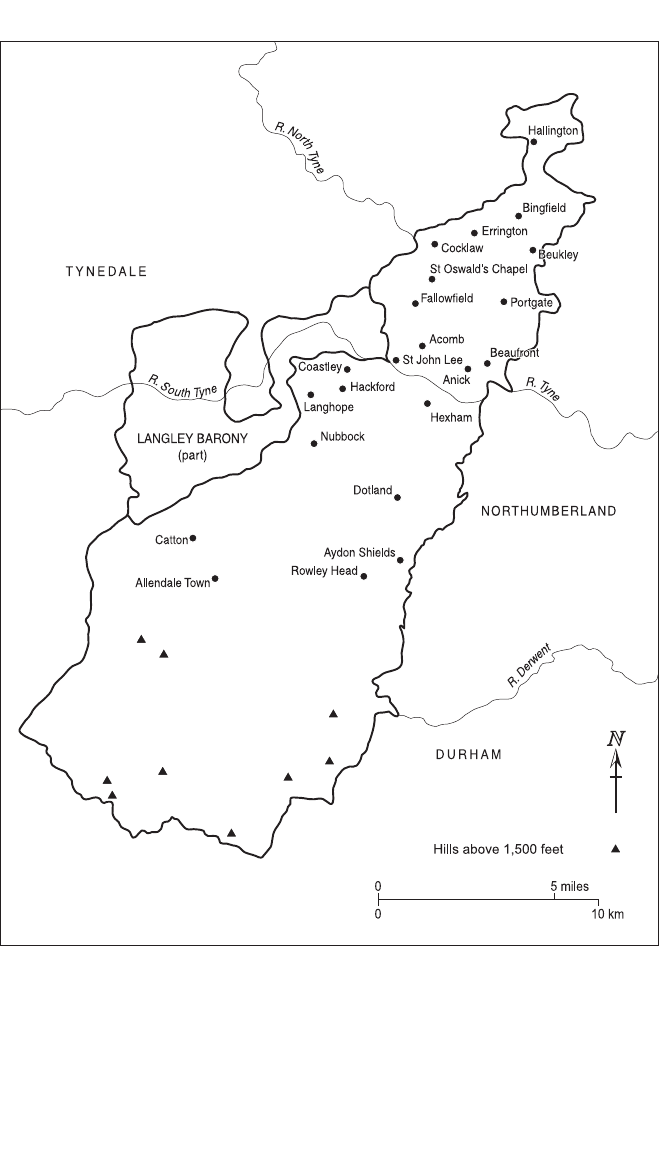

Compared with Durham or Tynedale, Hexhamshire was a relatively small

liberty, covering an area of just over ninety square miles. South of the

Tyne, its eastern border largely followed the Devil’s Water to the moor-

lands around Blanchland and Rookhope, where the watershed divided the

southern extremities of the liberty from Northumberland and Durham. To

the west the boundary followed the River West Allen, travelling north past

Staward and Langley until the junction of the North and the South Tyne.

A stretch of the North Tyne then separated Hexhamshire from Tynedale

until, south of Chollerton, the boundary followed the Erring Burn. e

remainder of the liberty’s border travelled east, south of Bavington, and

then south back to the Tyne west of Kirkheaton, Whittington and Halton.

Much of the liberty was not clearly de ned by major natural features,

and it is no surprise that there were disputes over common and bounda-

ries around Staward, Elrington, ockrington and Anick.

2

Nevertheless

Hexhamshire did occupy a contiguous and compact area: in contrast to

Tynemouthshire, geography posed few di culties for government or social

cohesion. Its ecclesiastical organisation, too, was coherent and uni ed, for

the liberty comprised a single parish, with chapelries at Allendale, Bing eld,

St Oswald in Cocklaw and St John Lee.

3

e liberty’s privileges, furthermore, provided a constitutional and insti-

tutional basis for the powerful exercise of lordship and – potentially – for the

development of a cohesive local community. Like Durham and Tynedale,

Hexhamshire was accepted as a ‘royal liberty’ where the king’s writ did not

run. As the jurors south of the Coquet put it in 1279, ‘the archbishop of

York holds Hexham and Allendale, and his writ runs there’.

4

As such, the

2

Reg. Gray, pp. 286–8, 290–1; NCS, ZSW/1/9; HN, II, iii, pp. 443–4; Northumb. Pets, no.

62. For a reference in 1269 to the bounds of the liberty ‘as they are observed on the day of

this agreement’, see NAR, pp. 160–1.

3

The modern civil parishes comprising the liberty are Allendale, West Allen, Acomb,

Bingfield, Hexhamshire, Sandhoe and Wall, and parts of Corbridge (Portgate) and

Whittington (Hallington).

4

NAR, p. 358; cf. RH, ii, p. 21.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 173M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 173 4/3/10 16:12:564/3/10 16:12:56

BORDER LIBERTIES AND LOYALTIES

174

Map 3 The Liberty of Hexhamshire

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 174M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 174 4/3/10 16:12:564/3/10 16:12:56

HEXHAMSHIRE AND TYNEMOUTHSHIRE

175

liberty gures only very rarely in the thirteenth- century records of royal

government – most notably during vacancies of the see of York, when it fell

into royal hands. And a er the episcopate of Walter Gray (1215–55) these

vacancies were rarely prolonged, although on a number of occasions the

temporalities of the see were in crown hands for periods of over a year.

5

As in the case of other liberties, of course, Hexhamshire’s privileges had

to evolve to keep pace with the developing organs and pretensions of royal

government – judicial, military and nancial. By at least the early thirteenth

century, the archbishop appointed his own justices to hear pleas in the

liberty during visitations of the royal eyre, and the liberty’s independence

from such eyres was respected throughout that century.

6

For most of this

period little is known of the liberty’s court outside sessions of eyre; but the

absence of Hexhamshire pleas from the records of the royal courts suggests

that the liberty served its inhabitants well.

7

It continued to keep abreast of

developments in royal justice in the later thirteenth and the fourteenth cen-

turies, as successive archbishops appointed justices of gaol delivery, oyer

and terminer, and the peace.

8

e challenge o ered to their judicial privi-

leges in the Quo Warranto proceedings of 1293 was perfunctory: although

the crown’s attorney argued that such royal rights as a chancery and justices

required explicit royal grant, the archbishop’s assertion of long usage was

soon accepted.

9

Hexhamshire’s privileges were more searchingly tested by the growing

demands of the ‘war- state’ for money, manpower and resources. Such

demands signi cantly curtailed the privileges of many other liberties else-

where in England. Almost all became subject to parliamentary taxation,

which royal writs and commissions instructed should be levied ‘within

and without liberties’; even jurisdictions as privileged as Bury St Edmunds

and the Isle of Ely might nd themselves unable to exclude the king’s

taxers.

10

And commissions of array that also contained the clause ‘within

and without liberties’ were o en similarly intrusive. It was rare for com-

missions to be issued to liberty- holders, and few joined the abbot of Battle

5

That is, in 1265–6, 1296–7, 1304–6, 1315–17, 1340–2 and 1405–7.

6

Hexham Priory, ii, p. 91; NAR, pp. 312, 357–9.

7

The references to liberty justices in Reg. Gray, pp. 227–8, 235, 248–9, all apparently relate

to 1227–8 and are to be associated with the 1227 Northumberland eyre. See otherwise

ibid., pp. 282–3; below, pp. 193–4.

8

For example, Reg. Giffard, no. 855; Reg. Romeyn, ii, no. 1225; Reg. Greenfield, i, no. 558;

NCH, iii, p. 30; and see also below, pp. 192–3.

9

PQW, p. 591; KB 27/137, m. 33d; cf. D. W. Sutherland, Quo Warranto Proceedings in the

Reign of Edward I, 1278–1294 (Oxford, 1963), pp. 109–10.

10

J. F. Willard, Parliamentary Taxes on Personal Property, 1290 to 1334 (Cambridge, MA,

1934), p. 31; E. Miller, The Abbey and Bishopric of Ely (Cambridge, 1951) p. 206.

M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 175M2107 - HOLFORD TEXT.indd 175 4/3/10 16:12:564/3/10 16:12:56