Hess Earl J. Field Armies and Fortifications in the Civil War: The Eastern Campaigns, 1861-1864

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

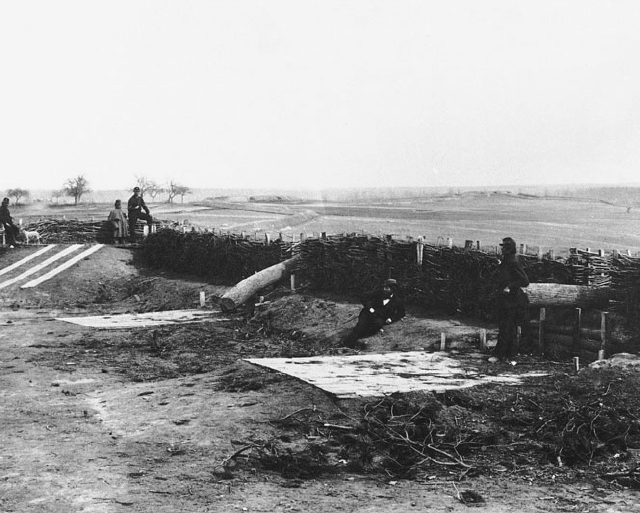

68 The Peninsula

Confederate fort, Centreville. Photographer George N. Barnard called this the prin-

cipal Rebel fort at Centreville. He exposed the view from atop the wide parapet.

Note the earthen banquette and artillery emplacement on the opposite face and the

loopholed stockade covering the gorge on the left of the view. Civilian houses and log

barracks can just be seen in the background. (Library of Congress)

The Confederate works at Manassas and Centreville haunted him for

months during the winter of 1861–62, and McClellan conceived of a strategic

advance that would take the positions in flank rather than approach them

from the front. The Federals would utilize their control of the Potomac River

and the Chesapeake Bay to land troops at Urbanna, fifty miles east of Rich-

mond on the Rappahannock River, and force the Confederates to evacuate

their works or lose their line of communications with the capital. McClellan

hesitated so long in setting this plan in motion that he gave the Rebels an

opportunity to decide, for their own reasons, that Manassas and Centreville

had to be evacuated. They were responding to a familiar problem: too few

troops to defend too much territory. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, commander of

Rebel forces in northern Virginia, was convinced that a position closer to the

Confederate capital would allow him to concentrate his limited manpower.

In a meeting between Johnston, President Davis, and the cabinet on Febru-

ary 19, 1862, everyone came to the conclusion that a withdrawal from Ma-

The Peninsula 69

nassas and Centreville was a foregone conclusion; the only question that

remained was when it should be conducted. Davis wanted it to be at the last

possible moment, but Johnston came out of the meeting believing it was

entirely at his discretion.

On March 5, Johnston received word of increased Federal activity and

immediately concluded it meant an advance on Manassas. He ordered an

evacuation of the troops and all supplies that could be taken. The Rebels

were gone by March 9. Johnston established a new defensive position on the

south side of the Rappahannock River on March 11.

The Federals were surprised by this sudden evacuation. The increased

activity that prompted Johnston to retreat was actually McClellan’s limited

moves to capture Rebel batteries along the Potomac River. A contraband

reported Manassas and Centreville empty soon after word arrived at Mc-

Clellan’s headquarters that the Rebels had abandoned the upper Potomac.

The general set his army out from Washington, D.C., on March 10 and oc-

cupied the railroad junction later that day. McClellan was suitably impressed

by the works at Manassas and Centreville. The latter were ‘‘formidable,’’ he

thought, ‘‘more so than Manassas,’’ even though ‘‘several dozen embrasures’’

were occupied by logs painted black. These ‘‘Quaker guns’’ caught the imagi-

nation of the public in a way that tended to belittle the danger of enemy

fortifications and the excessive caution displayed by the Union commander.

≥

With the Urbanna plan now moot, McClellan dusted off another proposal,

made as early as February 3, to outflank Richmond itself. He wanted to

land his army on the tip of the Yorktown Peninsula, formed by the near

convergence of the York River and the James River, and approach the capital

from the southeast. It would take advantage of Union control of the coast,

strike the enemy from an unexpected quarter, and avoid a lengthy overland

approach to Richmond.

∂

The plan was approved, and the first troop movements began on March

17. Over the next three weeks, some 400 ships transported 121,500 men, 44

batteries, more than 1,100 wagons, and more than 15,600 animals to the

Peninsula. The Union’s immense resources were demonstrated by Abraham

Lincoln’s insistence that large numbers of troops be left behind to guard the

approaches to Washington. Despite the huge army landed on the Peninsula,

there were enough men remaining to position more than 35,000 soldiers in

the Shenandoah Valley, over 10,000 at Manassas, more than 7,000 at War-

renton, and 18,000 to man the defenses of the capital.

∑

The Army of the Potomac also had a hefty engineer component, far

larger than that of any other Union force. In addition to Capt. James C.

Duane’s three-company U.S. Engineer Battalion, the 15th and 50th New York

70 The Peninsula

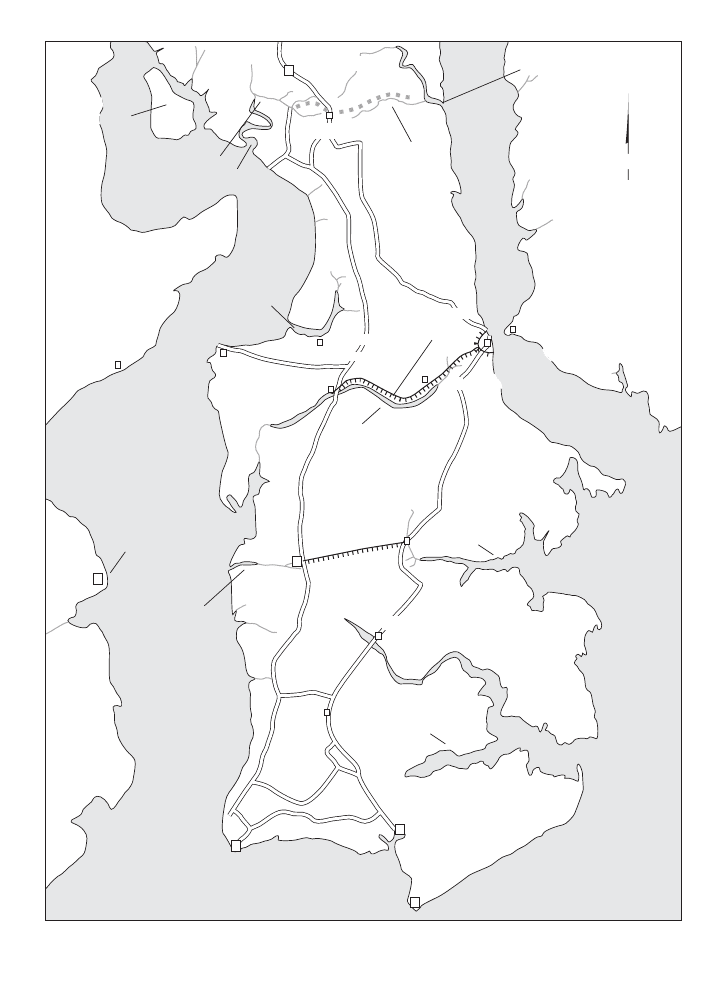

Quaker guns at Centreville. Painted black and stuck into embrasures, these logs could

easily be mistaken for cannon when viewed from a distance. This work has three

artillery platforms and a good hurdle revetment. Note the expansive countryside and

the large parapet that angles across the open space. (Massachusetts Commandery,

Military Order of the Loyal Legion and the U.S. Army Military History Institute)

Engineers constituted Brig. Gen. Daniel P. Woodbury’s Volunteer Engineer

Brigade. Thirty wagons carried entrenching tools for the engineers; tools for

the line infantry had to be supplied by McClellan’s quartermaster depart-

ment. The army carried trains of bridging equipment, with a total of 160

pontoons capable of spanning up to 1,500 yards of water. In addition to his

chief engineer, McClellan had the services of eight engineer officers of nearly

all ranks and levels of experience. Never again would the Army of the Poto-

mac have such lavish engineer assets for a campaign.

∏

McClellan landed this immense army on the Peninsula by utilizing a

Union toehold on its tip. Fortress Monroe was garrisoned by a small force

under Benjamin Butler, who had also fortified several points near the fort to

create a substantial area for the Army of the Potomac to deploy.

The area of McClellan’s operations was entirely in the Coastal Plain, or

Tidewater, of Virginia. Most of the land on the Peninsula is below 100 feet in

The Peninsula 71

elevation, rising to as much as 160 feet the closer one moves to Richmond.

The terrain is generally flat but cut by streams. What pass for hills and ridges

are really little more than irregularities or undulations in the landscape. The

Peninsula has a light and sandy soil that is easy to dig. A cover of mixed pines

and hardwoods with thick underbrush characterizes the vegetation. The

most serious obstacles in the landscape are sluggish, swampy rivers, such as

the Warwick and the Chickahominy. Even in dry weather these streams

could be a major impediment to an army; in wet weather, the entire land-

scape of the Peninsula turned into cloying mud and the sluggish streams

became deep, swift channels.

π

When McClellan was ready to advance in early April, he sent two columns

along the only good roads up the Peninsula. One paralleled the York River by

way of Howard’s Bridge to Yorktown, and the other skirted the James River

to Lee’s Mill on the lower reaches of the Warwick River opposite Yorktown.

The smaller roads were unpredictable. The general hoped to reach Yorktown

in ‘‘two rapid marches’’ and to use one column to cut off Rebel communica-

tions with Richmond and the other to invest the place. McClellan assumed

heavy works circled the small town. The retreating Rebels felled timber on

the roads north of Big Bethel, destroyed bridges, and abandoned a few small

earthworks.

∫

McClellan’s army moved almost imperceptibly through the first of three

Confederate lines on the Peninsula as it marched from Big Bethel to York-

town. The line was yet unfinished, and the Rebels never had a firm intention

to make their stand there. Known as the Poquosin River Line, it was the

shortest of the three defensive positions. Located four and a half miles north

of Big Bethel and five miles south of Yorktown, the Poquosin River Line had

two well-developed fortifications at Howard’s Bridge on the east and Young’s

Mill on the west. Howard’s Bridge lay near the head of the Poquosin River,

which starts nearly seven miles inland and flows into the York River. Young’s

Mill lay near the head of Deep Creek, which starts about two and a half miles

inland and flows into the James River. A space of nearly three miles, which

Maj. Gen. John B. Magruder called ‘‘wooded country’’ that was defended by

a very light line of works, lay between the two fortified posts. Magruder

toyed with the idea of defending this line, but he later admitted that, even

though anchored by substantial works on the flanks, the center was very

weak. He estimated it would take up to 25,000 men to hold it adequately,

and he had only 11,000 when he evacuated the line on April 5.

Ω

Young’s Mill had at least four small works for artillery located on the ends

of fingers of land that lay between the ravines that drained into Deep Creek.

The fortifications had been built by engineer Lt. Richard Lowndes Poor in

JAMES

RIVER

Y

O

R

K

R

I

V

E

R

College Creek

Tutter’s Neck

Skiff’s Creek

Warwick River

Deep Creek

N

o

r

t

h

w

e

s

t

B

r

a

n

c

h

Southwest

Branch

Poquosin

River

Queen’s Creek

B

a

c

k

R

i

v

e

r

Y

o

r

k

t

o

w

n

R

o

a

d

J

a

m

e

s

C

i

t

y

R

o

a

d

Jamestown

Island

Gloucester Point

Day’s

Point

Jones’s Mill

Pond

Mulberry

Island

Garrow’s

Point

Harden’s

Bluff

Williamsburg

Little

Bethel

Yorktown

Newport News

Hampton

Big Bethel

Young’s Mill

Lee’s Mill

Wynn’s Mill

Fort Huger

Fortress Monroe

Fort Boykin

Fort

Crafford

Fort Magruder

Skiff’s Creek

Redoubt

Howard’s

Bridge

N

Confederate Defense Lines on the Peninsula, April 1862

The Peninsula 73

October 1861. Poor was frustrated by the irregular terrain, for it allowed for

‘‘no regular system being used.’’ He had to fit the works to the fingers of land

and often was flustered by the troops assigned him as laborers. One infantry

officer had his men raise a parapet only half as high as Poor required. An-

other officer did not understand what a redan looked like. Poor staked out

the shape, explained it to the man, and then rode away to reconnoiter. When

he returned, he found that the officer ‘‘had played the old boy with the lines’’;

instead of a sharp chevron, the redan had an irregular U-shaped curve.

Despite these irritations, Poor managed to get the works into proper

shape. All were perched about twenty-five feet above the bottom of Deep

Creek and followed a general plan. None of them had embrasures, traverses,

or other flank protection for the field guns. There was a ditch in front of the

artillery emplacements and borrow pits behind the parapet as well, where

soldiers obtained more dirt to strengthen the parapet. The guns were placed

on the natural level of the earth, not dug down or built up. One of the four

works was semicircular, while the others were chevrons made by digging

two linear parapets.

Howard’s Bridge was defended by two redoubts on the north side of the

Poquosin River. The work to the west of the road had embrasures for four

guns, while the smaller work to the east had only one embrasure. South of

the river, the Confederates had constructed a curved infantry trench west of

the road. They cut down the timber within reach of all the works to form an

effective abatis. Drawings by topographic draftsman Robert Knox Sneden

show the works to be well made, with embrasures for the artillery and post-

and-board revetments for the parapets.

∞≠

Yorktown

Yorktown was already heavily fortified, and Magruder had the beginnings

of a good line that stretched across the Peninsula from that town and along

the north side of the Warwick River. This line surprised McClellan when the

head of his two columns encountered it. The cautious commander had no

thought of breaking through without reconnaissance, so his advance halted.

The presence of extensive fortifications on the east bank of the York River,

opposite Yorktown at Gloucester Point, prevented the navy from sailing up

the river to outflank the line. Thus, as McClellan informed Winfield Scott, ‘‘I

find myself with a siege before me.’’

McClellan played a bit loose with terms, for he really hoped to avoid what

he called ‘‘the tedious operations of a formal siege.’’ Instead, he planned to

bring up mortars and heavy artillery to batter his way through the Warwick

Line. He knew that he had immense superiority of numbers over Magruder,

74 The Peninsula

believing the Confederates had merely 15,000 men in line, but rather than

risk the lives of his soldiers, McClellan refused to act until he could use his

heavy ordnance. ‘‘Instant assault would have been simple folly,’’ he later

reported. Preparation and the accumulation of an avalanche of resources

was his plan. ‘‘The eclat of taking Yorktown will cover a delay of the few

days necessary to get everything in hand & ready for action,’’ he informed

his wife.

∞∞

McClellan’s preparations were hampered by his poor maps and the flat

landscape of the Peninsula, which made the Confederate positions difficult

to scout. His personal reconnaissance on April 6–7 convinced him that his

plan to overwhelm the Rebels with weight of ordnance was correct. Engineer

officers who were able to catch glimpses of the Rebel works confirmed Mc-

Clellan’s assumption that they were ‘‘formidable.’’ The Warwick River itself

was an effective obstacle, and the Confederates were rapidly reinforcing the

line. By April 7, McClellan was convinced there were 100,000 men facing his

85,000 troops, a gross error that he nevertheless continued to accept. Even

as his men went to work digging gun emplacements, McClellan began to call

for more troops.

∞≤

The Federals spent roughly ten days preparing the groundwork for their

operations against the Warwick Line, and McClellan was ready to begin

building gun emplacements by April 17. Initially, six batteries were planned,

situated from 1,500 to 2,000 yards from the Confederate works. Batteries

No. 1 and 2 were constructed in three days, but the others took much more

time and labor to complete. Connecting lines between these works were

begun on April 25. The lines were laid out by engineer officers, and enlisted

men dug them twelve feet wide and three feet deep. Most of the digging was

done at night; the Rebels could hear the noise but fired only randomly at the

workers.

∞≥

‘‘It seems the fight has to be won partially through the implements of

peace, the shovel, axe & pick,’’ commented a New Hampshire man as the

Federals dug into the sandy soil. The shape of things to come was apparent to

Robert Knox Sneden when he saw ‘‘Hundreds of new picks and shovels’’ de-

posited near the headquarters of the Third Corps. The enlisted men worked

in large groups. Ward Osgood of the 15th Massachusetts saw a gang of 100

soldiers building a gun emplacement behind a sheltering screen of trees. The

Rebels had failed to cut the timber very far in front of their line, so the

Yankees dug in on their side of the trees to obscure their work and cut

down the timber when finished. On the far right, where most of the dig-

ging was done, the Federals were excited when they realized they were

building works exactly where George Washington had entrenched during

The Peninsula 75

Federal Battery No. 1, Yorktown. The only one of McClellan’s batteries to open fire on

the Confederates, it was located on the Farinholt property. Note the use of sandbags

and gabions as revetment and the many ladders that gave access to the tops of the

traverses. (Massachusetts Commandery, Military Order of the Loyal Legion and the

U.S. Army Military History Institute)

the Yorktown siege. ‘‘The parallels which washington had built, eighty years

before, could be traced as easily as if erected only the day previous,’’ noted

the historian of the 2nd New Hampshire, ‘‘and oftentimes the same dirt

which had been thrown up by our forefathers to establish the Union was

shoveled over by us to perpetuate it.’’ They found numerous bullets, bones,

and other relics of the Revolution but carefully reburied the remains as they

were uncovered.

∞∂

McClellan’s engineer officers worked with a will, laying out battery em-

placements, scouting the Rebel lines, drawing maps, directing work details,

and sometimes placing themselves in danger. Lt. Orlando L. Wagner, an

engineer on the staff of the Third Corps, was laying out a new work near

Battery No. 7 when he was mortally wounded by enemy fire. Three enlisted

men had helped him use a steel tape to mark out the location of the work,

and Wagner had drawn sketches on a plane table shielded from the sun by a

76 The Peninsula

parasol. This probably drew Confederate attention, and a shell explosion so

damaged his arm that it had to be amputated. He died four days later.

Capt. William Heine, a Prussian observer who served as a topographical

engineer on the Third Corps staff, discovered long strips of freshly sawn

lumber nailed to trees. The Confederates had apparently placed them to

serve as artillery range markers. The boards, six inches wide, were nailed

vertically on the tree trunks and could be seen from quite a distance. Heine

and three enlisted men quickly tore them down.

∞∑

One of the reasons construction of the batteries was postponed until April

17 was McClellan’s need to organize supporting elements for the work. The

existing civilian roads were completely inadequate for the movement of sup-

plies, heavy guns, and men up to the line; also, planking had to be cut to

build revetments, and depots had to be established to feed and supply the

huge army. The Federals were helped greatly by the discovery of a working

sawmill less than two miles from the Rebel line along the Yorktown Road.

The same machinery that had recently been used to cut lumber for Rebel

barracks now was used to cut planks for Union earthworks. Other materials

essential for the construction of fortifications were gabions and fascines,

which made good revetments for gun embrasures or bulk for widening or

increasing the height of parapets.

∞∏

The military roads required a large expenditure of manpower, for they

had to be built for several thousands of yards in order to connect the new

battery emplacements with civilian roads. Michigan soldier Perry Mayo re-

ported that the roads ‘‘had to be graded as nice as a railroad’’ because guns

weighing as much as twenty tons had to be hauled over them. By the time the

artillery was ready to be emplaced, the spring rains had set in, turning the

Peninsula into a quagmire and negating much of the fine grading. The heavi-

est artillery presented the worst problem. It had to be transported up to

three miles from the landings to the batteries, and often the guns sank to

the axles of their carriages; they had to be manhandled out of the mire by

the unfortunate men of the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery and the 5th New

York Heavy Artillery. Supporting infantry had to build a corduroy road,

consisting of cut logs laid side by side, that was wide enough for two teams to

pass each other.

∞π

The Connecticut and New York artillerymen were responsible for Mc-

Clellan’s siege train, a special unit consisting of seventy heavy guns and mor-

tars. The biggest of these guns were two 200-pounder Parrotts and twelve

100-pounder Parrotts. The rest of the ordnance in the siege train consisted of

20- and 30-pounder Parrotts, a 4.5-inch Rodman, and forty-one mortars

ranging in caliber from eight to thirteen inches.

∞∫

The Peninsula 77

Most of the immense amount of labor that took place in the Union lines

throughout April was done willingly by the enlisted men, but a few Federals

began to balk toward the end of the month as they grew tired of the heavy

work. Sometimes the fault lay squarely with the officers, who did not take

the work seriously enough to supervise their men properly. An engineer

officer reported that some infantry officers in charge of work details pre-

ferred to lie in the shade of the trees rather than watch their men. Even when

the officers were willing, administrative foul-ups sometimes delayed the

work. If precise information about where the work parties were to go on a

given day was not conveyed, the parties appeared where the engineer of-

ficers were not, and vice versa.

∞Ω

But there was only one recorded instance of enlisted men refusing to dig.

Capt. Wesley Brainerd of the 50th New York Engineers was in charge of a

work detail at Battery No. 4 one rainy night when members of the 74th New

York went on strike. ‘‘The Officers used any means in their power to get the

men to work but to no purpose,’’ Brainerd recorded. He had to postpone the

planned work that night because the New Yorkers returned to their camp at

9:00 p.m. Brainerd reported the unit’s dereliction of duty to headquarters,

but nothing was done about it.

≤≠

Beyond this single instance of a refusal to dig, there were many cases of

soldiers putting only partial effort into their labor. Engineer Lt. Miles D.

McAlester reported near the end of the confrontation at Yorktown that ‘‘no

interest whatever in the work could be excited in the officers, and that there-

fore the men were generally idle.’’ At the same time, Barnard was forced to

report that ‘‘officers and men from Hooker’s division worked badly.’’ To give

them their due, the infantrymen were not used to such heavy labor, and it

was expected of these green soldiers in a concentrated form under a spring

sky that often deluged them with more rain than they needed. Robert Knox

Sneden noted how the heavy labor taxed the infantrymen. ‘‘Those who work

in the trenches grow thin,’’ he wrote, ‘‘and officers and men complain of

being overworked. The field hospitals show it.’’ Orders went out to issue

three gills of whiskey per day for the men, but the mud and rain often caused

sickness even with this internal fortification.

≤∞

McClellan’s management of the ‘‘siege’’ of Yorktown cannot be faulted.

Once he had decided to emplace batteries and bombard his way through the

Warwick Line, his men spent the right amount of time and labor preparing

the works to achieve that goal. Yet the general felt compelled to explain why

it was taking him so long to advance up the Peninsula. ‘‘I can’t go ‘with a rush’

over strong posts,’’ he wrote his wife. ‘‘I must use heavy guns & silence their

fire—all that takes much time & I have not been longer than the usual time