Henslin James M. Sociology: A Down to Earth Approach

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

to increase the sales of the product? Some drug companies even ghostwrite articles for

medical journals that present research about how good their drugs are—and then look for

doctors to list as authors (Ross et al. 2008). With conflict of interest so powerful, new laws

are being passed to curb these practices (Meier 2009).

At Harvard University, the conflict of interest with drug companies has taken an in-

teresting turn. Medical students have protested that when their professors are receiving

money from a pharmaceutical company, what they teach is no longer objective. In re-

sponse to their protest, teachers in the medical school must now inform their students of

all ties they have with drug companies (Wilson 2009).

Medical Fraud

One doctor billed Medicare for treatment of a

patient’s eye—the only problem was that the

patient was missing that eye (Levy 2003). A

dentist charged Medicare for 991 procedures

in a single day. In a typical workday, that

would come to one every 36 seconds (Levy and

Luo 2005). A psychiatrist in California had sex

with his patient—and charged Medicaid for

the time. (Geis et al. 1995)

These are not isolated incidents—they are just

some of the most outrageous. With 3 million

Medicare claims filed every day, physicians are

not likely to be audited (Johnson 2008). Many

doctors have not been able to resist the tempta-

tion to cheat.

Do you recall the section on white collar crime

in Chapter 8, where I pointed out that some

white-collar crime goes far beyond money, that it

harms and kills people? So it is with this white-collar crime. A pharmacist in Kansas City was

so driven by greed that he diluted the drugs he sold for patients in chemotherapy (Belluck

2001). And what do you think Guidant Corporation did when it discovered that its heart de-

fibrillators, which are surgically implanted in patients, could short-circuit and kill patients?

Tell the patients and doctors? You would think so. Instead, the company kept selling the de-

fective model while it developed a new one. Several patients died when their defibrillators

short-circuited (Meier 2005, 2006).

Then there is Bayer, that household name you trust when you reach for aspirin. Bayer

also makes Trasylol, a drug given after heart surgery. Bayer found that its drug had a few

slight side effects—it could increase the risk of strokes, damage kidneys, and cause heart

failure and death. Did Bayer warn doctors that they might be killing their patients? Not

at all. In Bayer’s own words, it “mistakenly did not inform” the Federal Drug Adminis-

tration of the study (Harris 2006). In the same vein that Bayer made its statement, I will

assume that the $200 million annual sales of this drug had nothing to do with Bayer

making this mistake.

Greed can be so enticing that it ensnares even outstanding individuals, distorting their

ethics and sense of reality. A top medical researcher at Harvard who was also the head of

pediatric research at Massachusetts General Hospital told the drug company, Johnson &

Johnson, that if they funded his research, his findings would benefit the company (Harris

2009). No honest researcher knows in advance what research findings will be.

Sexism and Racism in Medicine

In Chapter 11 (pages 310–311), we saw that physicians don’t take women’s health com-

plaints as seriously as they do those of men. As a result, surgeons operate on women after

the women’s heart disease has progressed farther, which makes it more likely that the

women will die from the disease. This sexism is so subtle that the physicians are not even

Issues in Health Care 571

Today’s medical fraud is more sophisticated than this Specto-Chrome of years

past, a machine that could cure anything with colored lights, but the goal is

always the same, money.

aware that they are discriminating against women. Some sexism in medicine, in contrast,

is blatant. One of the best examples is the bias against women’s reproductive organs that

we reviewed in Chapter 11 (page 312).

Racism is also an unfortunate part of medical practice. In Chapter 12, we reviewed

racism in surgery and in health care after heart attacks. You might want to review these

materials on page 339.

The Medicalization of Society

As we have seen, childbirth and women’s reproductive organs have come to be defined as

medical matters. Sociologists use the term medicalization to refer to the process of turn-

ing something that was not previously considered a medical issue into a medical matter.

“Bad” behavior is an example. If a psychiatric model is followed, crime becomes not will-

ful behavior that should be punished, but a symptom of unresolved mental problems that

were created during childhood. These problems need to be treated by doctors. The human

body is a favorite target of medicalization. Characteristics that once were taken for

granted—such as wrinkles, acne, balding, sagging buttocks and chins, bulging stomachs,

and small breasts—have become medical problems, all in need of treatment by physicians.

As usual, the three theoretical perspectives give us contrasting views of the medicalization

of such human conditions. Symbolic interactionists would stress that there is nothing inher-

ently medical about wrinkles, acne, balding, sagging chins, and so on. It is a matter of def-

inition: People used to consider such matters as normal problems of life; now they are

starting to redefine them as medical problems. Functionalists would stress that the medical-

ization of such conditions is functional for the medical establishment. It strengthens the

medical establishment by broadening its customer base. Conflict sociologists would argue

that such medicalization indicates the growing power of the medical establishment: The

more conditions of life that physicians can medicalize, the greater their profits and power.

Medically Assisted Suicide

To consider medically assisted suicide takes us face to face with controversial issues that

are both disturbing and difficult to resolve. Should doctors be able to write lethal prescrip-

tions for terminally ill patients? Some take the position that this will relieve suffering and

help people to die with dignity. Others say that such laws would simply legalize murder.

Let’s explore these issues in the following Thinking Critically section.

572 Chapter 19 MEDICINE AND HEALTH

medicalization the transfor-

mation of a human condition

into a matter to be treated by

physicians

euthanasia mercy killing

Thinking CRITICALLY

Should Doctors Be Allowed to Kill Patients?

Except for the name, this is a true story:

Bill Simpson, in his 70s, had battled leukemia for years. After his spleen was removed, he devel-

oped an abdominal abscess. It took another operation to drain it.A week later, the abscess filled

and required more surgery.Again the abscess returned. Simpson began to go in and out of con-

sciousness. His brother-in-law suggested euthanasia.The surgeon injected a lethal dose of mor-

phine into Simpson’s intravenous feeding tubes.

At a medical conference in which euthanasia, mercy killing, was discussed, a cancer

specialist who had treated thousands of patients announced that he had kept count of the

patients who had asked him to help them die.“There were 127 men and women,” he said.

He paused, and then added,“And I saw to it that 25 of them got their wish.” Thousands of

other physicians have done the same (Nuland 1995).

When a doctor ends a patient’s life, such as by injecting a lethal drug, it is called active eu-

thanasia. To withhold life support (nutrients or liquids) is called passive euthanasia. To re -

move life support, such as disconnecting a patient from oxygen falls somewhere in between.

The result, of course, is the same.

Issues in Health Care 573

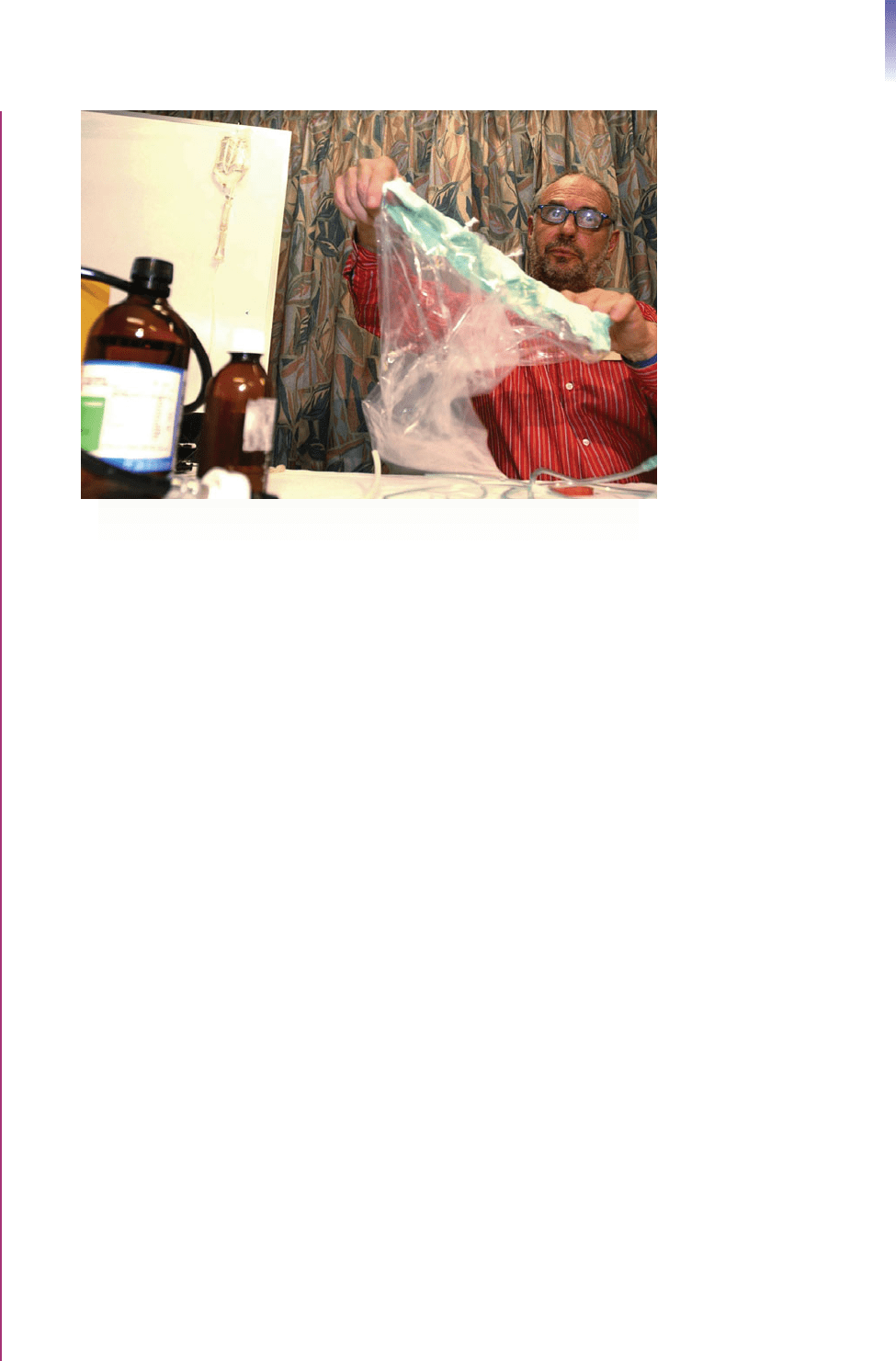

Dr. Phillip Nitschke (“Dr. Death”) showing his euthanasia items at a “Killing Me Softly”

conference in Sidney, Australia. The bag he is holding is connected by a hose to a generator and

placed over someone’s head. The individual dies by carbon dioxide poisoning.

Two images seem to dominate the public’s ideas of euthanasia: One is of an individual

devastated by chronic pain. The doctor mercifully helps to end that pain by performing

euthanasia. The second is of a brain-dead individual—a human vegetable—who lies in a

hospital bed, kept alive only by machines. How accurate are these images?

We have the example of Holland. There, along with Belgium, euthanasia is legal. Incredi-

bly, in about 1,000 cases a year, physicians kill their patients without the patients’ express

consent. In one instance a doctor ended the life of a nun because he thought she would

have wanted him to do so but was afraid to ask because it was against her religion. In an-

other case, a physician killed a patient with breast cancer who said that she did not want

euthanasia. In the doctor’s words,“It could have taken another week before she died. I

needed this bed” (Hendin 1997, 2000).

Some Dutch, concerned that they could be euthanized if they have a medical emergency,

carry “passports” that instruct medical personnel that they wish to live. Most Dutch, how-

ever, support euthanasia. Many carry another “passport,” one that instructs medical person-

nel to carry out euthanasia (Shapiro 1997).

In Michigan, Dr. Jack Kevorkian, a pathologist (he didn’t treat patients—he studied dis-

eased tissues) decided that regardless of laws, he had the right to help people commit sui-

cide. He did, 120 times. Here is how he described one of those times:

I started the intravenous dripper, which released a salt solution through a needle into her vein,

and I kept her arm tied down so she wouldn’t jerk it. This was difficult as her veins were fragile.

And then once she decided she was ready to go, she just hit the switch and the device cut off

the saline drip and through the needle released a solution of thiopental that put her to sleep in

ten to fifteen seconds. A minute later, through the needle flowed a lethal solution of potassium

chloride. (Denzin 1992)

Kevorkian taunted authorities. He sometimes left bodies in vans and dropped them off at

hospitals. Although he provided the poison, as well as a “death machine” that he developed

to administer the poison, and he watched patients pull the lever that released the drugs,

Kevorkian never touched that lever. Frustrated Michigan prosecutors tried Kevorkian for

murder four times, but four times juries refused to convict him. Then Kevorkian made a

fatal mistake. On national television, he played a videotape showing him giving a lethal injec-

tion to a man who was dying from Lou Gehrig’s disease. Prosecutors put Kevorkian on trial

again. This time, he was convicted of second-degree murder and was sentenced to 10 to 25

years in prison. Kevorkian was released after 8 years. To get out, he had to promise not to

kill anyone else (Wanzer 2007).

Curbing Costs: From Health Insurance

to Rationing Medical Care

We have seen some of the reasons why the cost of medical care in the United States has

soared: advanced—and expensive—technology for diagnosis and treatment, a growing

elderly population, tests performed as defensive measures rather than for medical reasons,

malpractice insurance, and health care as a commodity to be sold to the highest bidder.

As long as these conditions exist, the price of medical care will continue to outpace infla-

tion. Let’s look at some attempts to reduce costs.

Health Maintenance Organizations. Some medical companies—health maintenance

organizations (HMOs)—charge an annual fee in exchange for providing medical care to

a company’s employees. Prices are lower because HMOs bid against one another. What-

ever money is left over at the end of the year is the HMO’s profit. While this arrangement

eliminates unnecessary medical treatment, it can also reduce necessary treatment. The re-

sults are anything but pretty.

Over her doctor’s strenuous objections, a friend of mine was discharged from the hospi-

tal even though she was still bleeding and running a fever. Her HMO representative said

he would not authorize another day in the hospital. After suffering a heart attack, a man

in Kansas City, Missouri, needed surgery that could be performed only at Barnes Hospi-

tal in St. Louis, Missouri. The HMO said, “Too bad. That hospital is out of our service

area.” The man died while appealing the HMO decision (Spragins 1996). Some doctors

also have HMOs. One doctor, who works for a hospital, noticed a lump in her breast.

She went to the x-ray department to get a mammogram, but her own hospital said she

couldn’t have one. Her HMO allowed one mammogram every two years, and she had had

one 18 months before. After a formal appeal, she was granted an exception. She had breast

cancer. (“What Scares Doctors?” 2006)

The basic question, of course, is: At what human cost do we reduce spending on med-

ical treatment?

Diagnosis-Related Groups. To curb spiraling costs, the federal government has classified all

illnesses into diagnosis-related-groups (DRGs) and has set an amount that it will pay for the

574 Chapter 19 MEDICINE AND HEALTH

The cartoonist has captured

an unfortunate reality of U.S.

medicine.

Only in Oregon (since 1997) and Washington (since 2008) is it legal for doctors to assist

in suicide, and only under strict rules. If Kevorkian had lived in Oregon or Washington, and

he hadn’t begun killing patients until those years, he would never have been convicted.

For Your Consideration

Do you think Oregon and Washington are right? Why? In the future, do you think other

states will approve medically assisted suicide?

In addition to what is reported here, Dutch doctors also kill newborn babies who have

serious birth defects (Smith 1999;“Piden en Holanda . . .” 2004).Their justification is that if

these children live they would not have “quality of life.” Would you support this?

treatment of each illness. Hospitals make a profit if they move patients through the system

quickly—if they discharge patients before the allotted amount is spent. As a consequence,

some patients are discharged before they have recovered. Others are refused admittance be-

cause they appear to have a “worse than average” case of a particular illness: If they take longer

to treat, they will cost the hospital money instead of bringing them a profit.

National Health Insurance

The van from Hollywood Presbyterian Hospital pulled up to the curbside in the center of skid

row in Los Angeles, California. The driver got out and walked to the passenger side. As several

people watched, she opened the door and helped a paraplegic man out. As she drove away, leav-

ing the befuddled man, people shouted at her, “Where’s his wheelchair? Where’s his walker?”

Someone called 911. The police found the man crawling in the gutter, wearing a flimsy,

soiled hospital gown and trailing a broken colostomy bag.

“I can’t think of anything colder than that,” said an L.A. detective. “It’s the worst area of

skid row.” (Blankstein and Winton 2007)

This is a blatant example of dumping, hospitals discharging unprofitable patients. Seldom

is dumping as dramatic as in this instance, but dumping is not unusual. Dumping is one

consequence of a system that puts profit ahead of patient care. With 47 million Ameri-

cans uninsured (Statistical Abstract 2009:Table 147), pressure has grown for the govern-

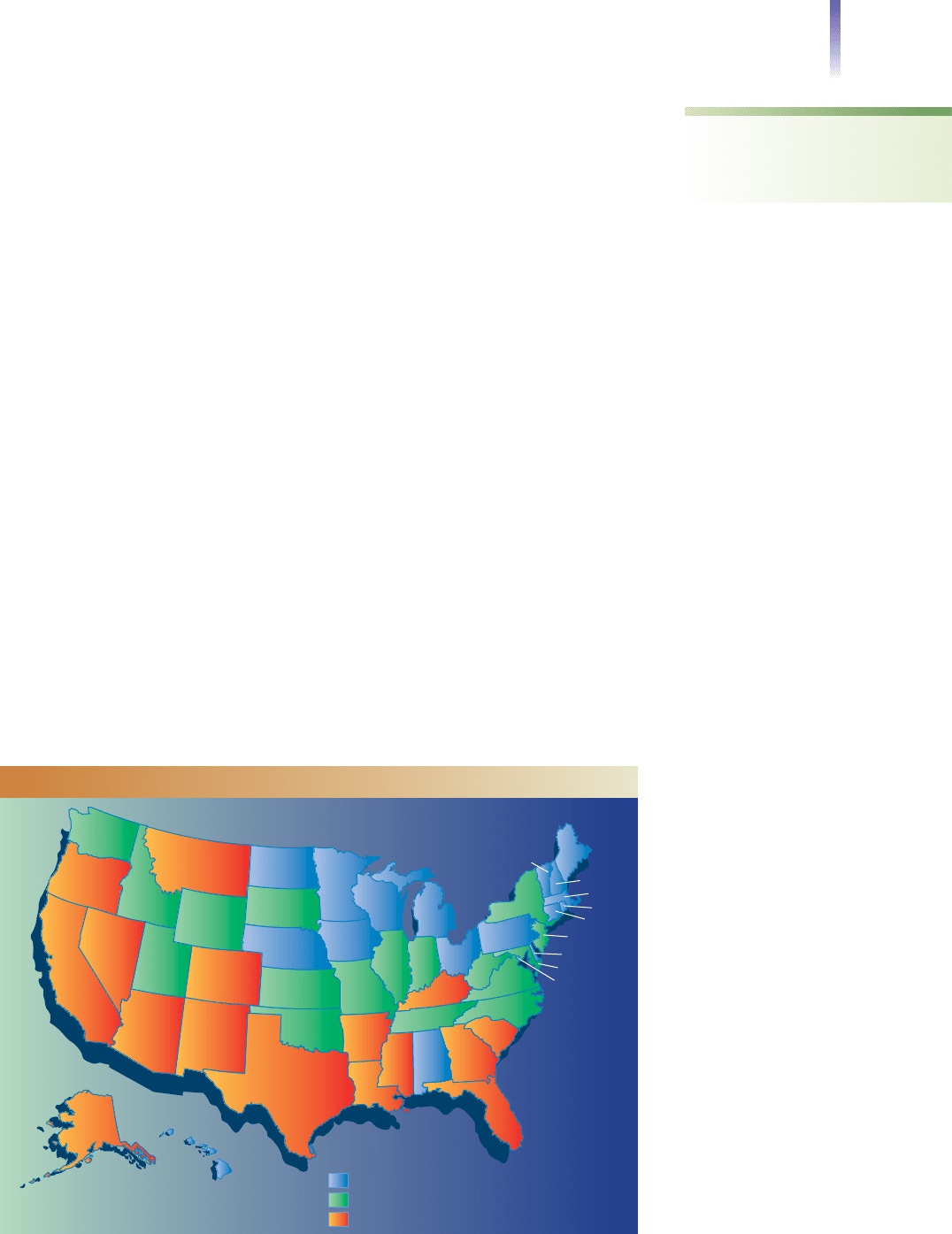

ment to provide national health insurance. What patterns do you see in the Social Map

below, which shows how the uninsured are distributed among the states?

Advocates of national health insurance point out that centralized, large-scale purchases

of medical and hospital supplies will reduce costs. They also stress that national health in-

surance will solve the problem of the poor receiving inferior medical care. Opponents

stress that national health insurance will bring expensive red tape. They also ask why any-

one would think that federal agencies—such as those that run the post office—should be

entrusted with administering something as vital as the nation’s health care. Proponents

reply that right now no one is in charge of it. This debate is not new, and even if some

form of national health insurance is adopted, the arguments will continue.

Issues in Health Care 575

Less than average: 5.5 to 11.9

Average: 12.1 to 15.6

Higher than average: 15.8 to 25.1

The percentage of a state’s

residents who have no medical insurance

AK

SC

NC

VA

WA

OR

CA

NV

ID

MT

WY

AZ

NM

CO

ND

SD

NE

KS

OK

TX

MN

IA

MO

AR

LA

WI

IL

KY

TN

MS

AL

GA

FL

IN

MI

WV

PA

NY

ME

NH

MA

RI

CT

NJ

DE

MD

DC

HI

VT

UT

OH

FIGURE 19.6 Who Lacks Medical Insurance?

Source: By the author. Based on Statistical Abstract of the United States 2011:Table 152.

dumping the practice of

sending unprofitable patients to

public hospitals

Note: The range is broad, from 8.6 percent who lack medical insurance in Rhode Island to

24.5 percent in Texas.

Maverick Solutions

Single ear infections $40

Simple cuts with suture removal $95

Ingrown toenail corrections $150

The Tennessee doctor who put this billboard up outside his clinic had grown tired of hav-

ing to hire people to fill out and submit insurance claims, and then waiting to get paid,

or having the forms rejected and having to resubmit them (Brown 2007). To avoid these

frustrations and the cost of dealing with insurance companies, this doctor, like a few oth-

ers, opened a pay-as-you-go clinic. No insurance allowed. Payments only by cash or credit

card. With no billing costs, the doctors can charge less.

Other doctors are lowering costs by replacing individual consultations with group care.

They meet with a group of patients who have similar medical conditions. Eight or ten

pregnant women, for example, go in for their obstetrics checkup together. This allows

the doctor more time to discuss medical symptoms and treatments, and, at the same time,

to charge each patient less. The patients also benefit from the support and encourage-

ment of people who are in their same situation (Bower 2003).

Rationing Medical Care. The most controversial suggestion for how to reduce medical

costs is to ration medical care. The argument is simple: We cannot afford to provide all the

available technology to everyone, so we have to ration it. No easy answer has been found for

this dilemma, the focus of the Sociology and the New Technology box on the next page.

Threats to Health

Let’s look at major threats to health, both in the United States and worldwide.

HIV/AIDS

In 1981, the first case of AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) was documented.

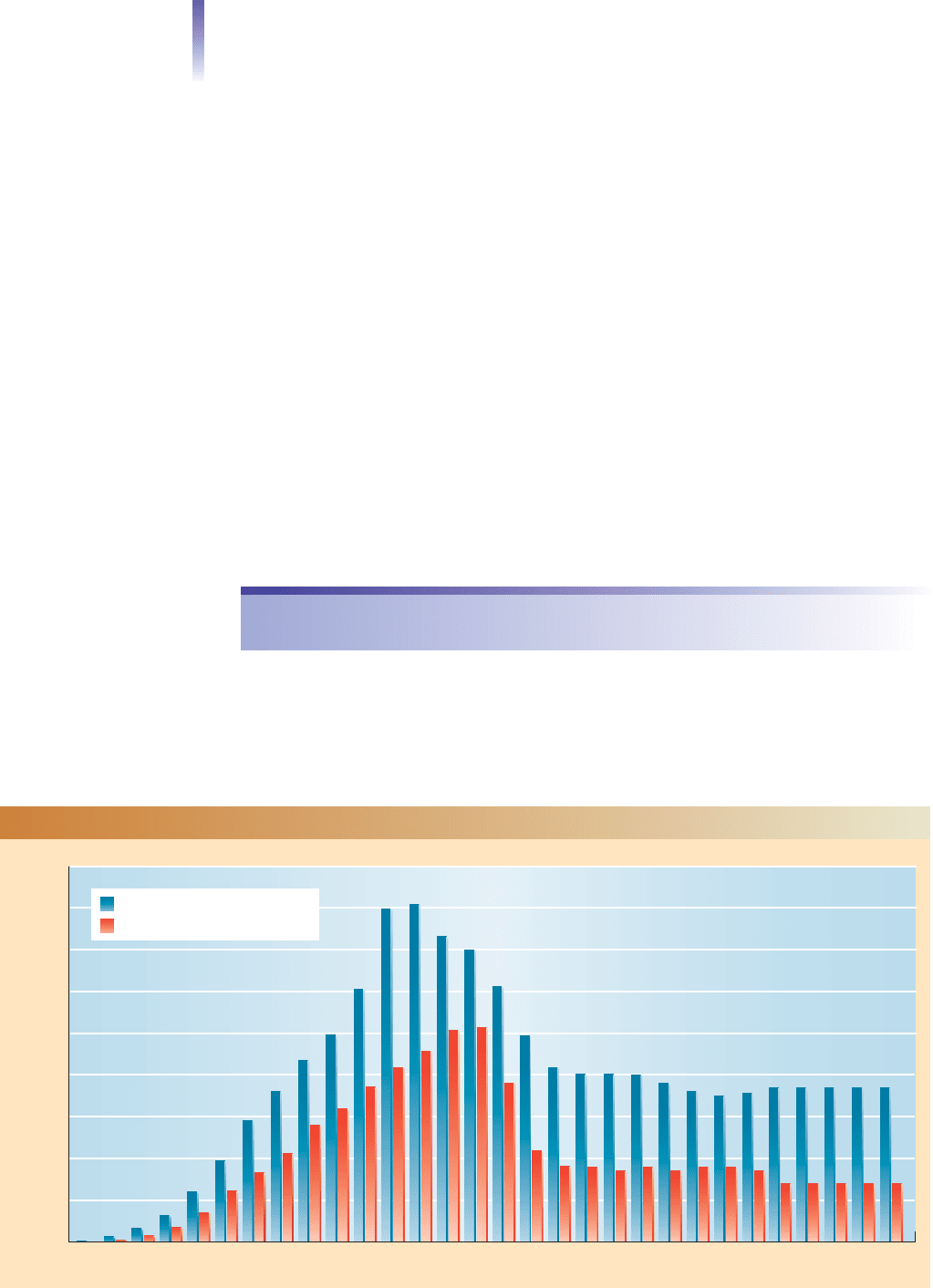

Since then, about 600,000 Americans have died from AIDS. As you can see from Figure 19.7,

576 Chapter 19 MEDICINE AND HEALTH

0

40,000

30,000

20,000

10,000

50,000

60,000

70,000

80,000

90,000

Year

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007*

2009*

2010*

2008*

New cases reported that year

Deaths reported that year

FIGURE 19.7 The Path of AIDS in the United States

Note: Alternative estimates indicate a higher incidence of new cases of HIV (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2008c).

*Indicates the author’s projections.

Sources: By the author. Based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2003:Table 21; 2008a:Tables 1, 7.

Threats to Health 577

SOCIOLOGY and the

NEW TECHNOLOGY

Who Should Live, and Who Should

Die? The Dilemma of Rationing

Medical Care

A 75-year old woman enters the emergency

room, screaming and in tears from severe pain.

She is suffering from metastatic cancer (cancer that

has spread through her body). She has only weeks to

live, and she needs immediate admittance to the

intensive care unit.

At this same time, a 20-year old woman, severely

injured in a car wreck, is wheeled into the emer-

gency room.To survive, she must be admitted to the

intensive care unit.

As you probably guessed, there is only one unoccu-

pied bed left in intensive care.What do the doctors do?

This story, not as far-fetched as you might think, distills a

pressing situation that faces U.S. medical health care.

Even though a particular treatment is essential to care

for a medical problem, there isn’t enough of it to go

around to everyone who needs it. Other treatments are

so costly that they could bankrupt society if they were

made available to everyone who had a particular med-

ical problem.Who, then, should receive the benefits of

our new medical technology?

In the situation above, medical care would be ra-

tioned. The young woman would be admitted to inten-

sive care, and the elderly person would be directed

into some ward in the hospital. But what if the elderly

woman had already been admitted to intensive care?

Would physicians pull her out? That is not as easily

done, but probably.

Consider the much less dramatic, more routine

case of dialysis, the use of machines to cleanse the

blood of people who are suffering from kidney disease.

Dialysis is currently available to anyone who needs it,

and the cost runs several billion dollars a year. Many

wonder how the nation can afford to continue to pay

this medical bill. Physicians in Great Britain act much

like doctors would in our opening example. They ra-

tion dialysis informally, making bedside assessments of

patients’ chances of survival and excluding most older

patients from this treatment (Aaron et al. 2005).

Modern medical technology is marvelous. People walk

around with the hearts, kidneys, livers, lungs, and faces of

deceased people. Eventually, perhaps, surgeons will be

able to transplant brains. The costs are similarly astound-

ing. Look again at Figure 19.4 on page 566. Our national

medical bill runs more than $2 trillion a year (Statistical

Abstract 2011:Table 130). Frankly, I can’t understand what

a trillion of anything is. I’ve tried, but the number is just

too high for me to grasp. Now there are two of these

trillions to pay each year.Where can we get such fantastic

amounts? How long can we continue to pay them? These

questions haunt our medical system, making the question

of medical rationing urgent.

The nation’s medical bill will not flatten out. Rather,

it is destined to increase. Medical technology, including

new drugs, continues to advance—and to be costly.

And we all want the latest, most advanced treatment.

Then there is the matter we covered in Chapter 13,

that people are living longer and the number of elderly

is growing rapidly. It is the elderly who need the most

medical care, especially during their last months of life.

The dilemma is harsh: If we ration medical treat-

ment, many sick people will die. If we don’t, we will in-

debt future generations even further.

For Your Consideration

At the heart of this issue lie questions not only of cost

but also of fairness. If all of us can’t have the latest, best,

and most expensive medical care, then how can we dis-

tribute medical care fairly? Use ideas, concepts, and prin-

ciples from this and other chapters to develop a proposal

for solving this issue. How does this dilemma change if

you view it from the contrasting perspectives of conflict

theory, functionalism, and symbolic interactionism?

If we ration medical care, what factors would be fair

to consider? If age is a factor, for example, should the

younger or the older get preferred treatment? Why? If

you are about 20 years old, your answer is likely to be

a quick,“the younger.” But is the matter really that

simple? What about a 40-year old who has a 5-year old

child, for example? Or a 55-year old nuclear physicist?

Or the U.S. president? (OK, why bring that up? He or

she will never get the same medical treatment as we

get. But, wait, isn’t that the point?)

The high cost of some medical treatments, such as dialysis,

shown here, has led to the issue of rationing medical care.

in the United States this disease has been brought under control. New

cases peaked in 1993, and deaths peaked in 1995. This disease is far

from conquered, however. Each year about 35,000 Americans are in-

fected with the HIV virus, and about 14,000 die from it. For the

500,000 Americans who receive treatment, HIV/AIDS has become a

chronic disease that they live with (Centers for Disease Control

2008a:Table 8).

Globally, in contrast, the epidemic is exploding, with 2.7 mil-

lion new HIV infections a year (UNAIDS 2008). Every minute of

every hour of every day, about 5 people become infected with HIV.

Over 40 million people have died from AIDS, but the worst is yet

to come. The most devastated area is sub-Saharan Africa. Although

this region has just 10 percent of the world’s population, it ac-

counts for 67 percent of all people living with HIV and 72 percent

of the world’s deaths from AIDS. The death toll in this region is so

high that the average person dies at age 50. The lowest life ex-

pectancy in the world is in Swaziland. There, the average person is

dead by age 33 (Haub and Kent 2008). As Figure 19.8 illustrates,

Africa is the hardest-hit region of the world.

Let’s look at some of the major characteristics of this disease.

Origin. The question of how HIV/AIDS originated baffled sci-

entists for two decades, but they finally traced its genetic sequences

back to the Congo (Kolata 2001). Apparently, the virus was pres-

ent in chimpanzees and was somehow transmitted to humans.

How this crossover occurred is not known, but the best guess is

that hunters were exposed to the animals’ blood as they slaugh-

tered them for meat.

The Transmission of HIV/AIDS. The only way a person can become infected with the

HIV virus is if bodily fluids pass from one person to another. HIV is most commonly

transmitted through blood, semen, and vaginal secretions, but nursing babies can also get

HIV through the milk of their infected mothers. Since the HIV virus is present in all bod-

ily fluids (including sweat, tears, spittle, and urine), some people think that HIV can also

be transmitted in these forms. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control, however, stresses that

HIV cannot be transmitted by casual contact in which traces of these fluids would be ex-

changed. Figure 19.9 on the next page compares how U.S. men and women get infected.

Gender, Circumcision, and Race–Ethnicity.

In the United States, AIDS hits men the hard-

est, but the proportion of women has been

growing. In 1982, only 6 percent of AIDS cases

were women, but today it is 26 percent (Centers

for Disease Control 1997; 2008b). In sub-

Saharan Africa, AIDS is more common among

women (UNAIDS 2008). Researchers have

found that circumcision reduces a man’s chance

of getting infected with HIV by about half (Mc-

Neil 2006). Because circumcision is not widely

practiced in sub-Saharan Africa, to help stem

the epidemic Israel is sending in circumcision

teams (Kraft 2008).

HIV/AIDS is also related to race–ethnicity.

One of the most startling examples is this:

African American women are 19 times more

likely to come down with AIDS than are white

women (Centers for Disease Control 2008b).

Figure 19.10 on the next page summarizes

578 Chapter 19 MEDICINE AND HEALTH

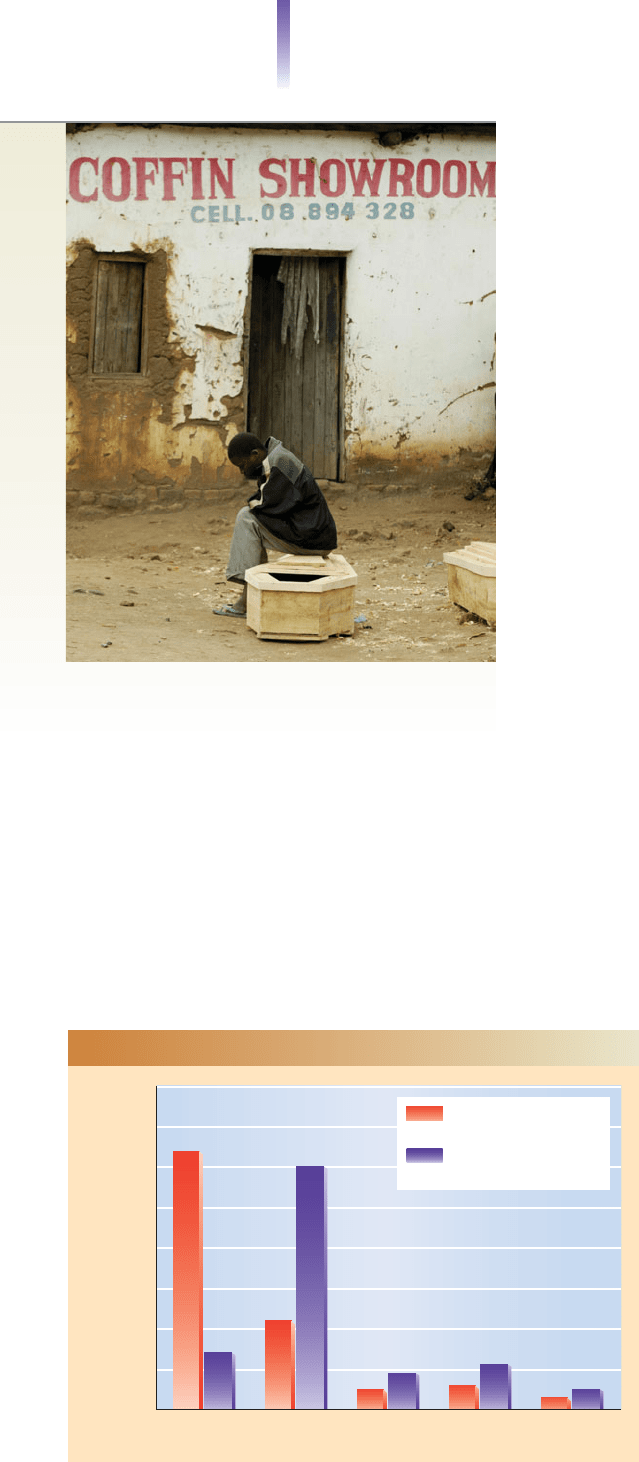

Africa

64%

14%

22%

5%

9%

60%

11%

3%

5%

6%

Asia Central and

South America

Europe North

America

Percentage

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0

80

%

Percent of the worlds

AIDS cases

Percent of the world’s

population

FIGURE 19.8 AIDS: A Global Glimpse

Source: By the author. Based on UNAIDS 2006; Haub and Kent 2008.

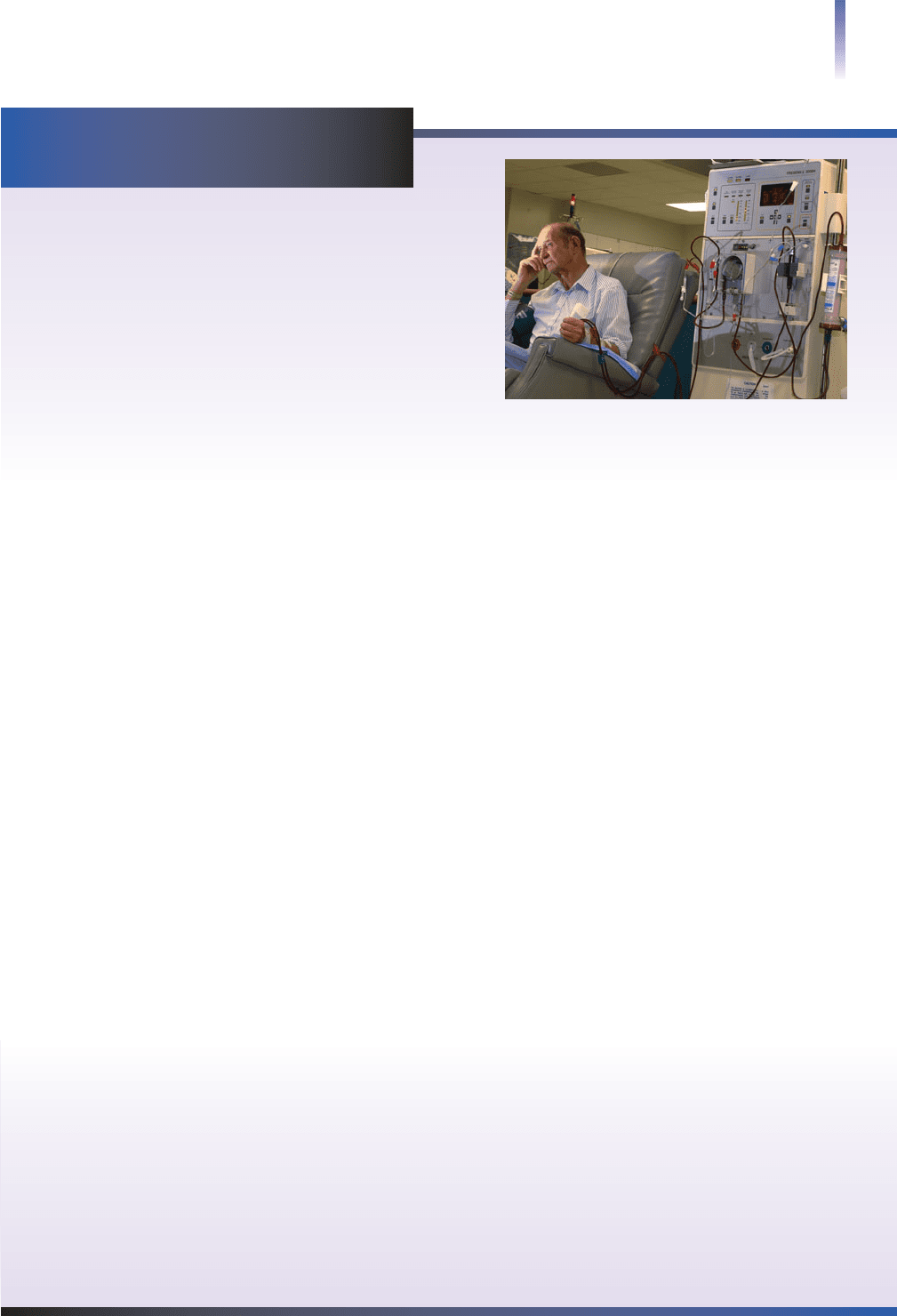

With AIDS devastating Malawi and other areas of Africa,

“coffin shops” have become a common sight.This one is in

Blantyre, Malawi.

racial–ethnic differences in this disease. The reason for the differences

shown on this figure is not genetic. No racial–ethnic group is more sus-

ceptible to AIDS because of biological factors. Rather, risks differ be-

cause of social factors, such as the use of condoms and the number of

drug users who share needles.

The Stigma of AIDS. Recall how I stressed at the beginning of this

chapter how social factors are essential to understanding health and ill-

ness. The stigma associated with AIDS is a remarkable example. Some

people refuse even to be tested because they fear the stigma they would

bear if they test HIV-positive. One unfortunate consequence is the con-

tinuing spread of AIDS by people who “don’t want to know.” Even some

governments have put their heads in the sand. Chinese officials, for ex-

ample, at first refused to admit that they had an AIDS problem, but

now they are more open about it. If this disease is to be brought under

control, its stigma must be overcome: AIDS must be viewed like any

other lethal disease—as the work of a destructive biological organism.

Is There a Cure for AIDS? As you saw on Figure 19.7 (page 576),

the number of AIDS cases in the United States increased dramatically,

reached a peak, and then declined. With such a remarkable decline,

have we found a cure for AIDS?

With thousands of scientists doing research, the media have her-

alded each new breakthrough as a possible cure. The most promising

treatment, the one that lies behind the drop in deaths shown in Fig-

ure 19.7, was spearheaded by David Ho, a virologist (virus re-

searcher). If patients in the early stages of the disease take a “cocktail”

of drugs (a combination of protease, fusion, and integrase inhibitors),

their immune systems rebound. Antiretroviral therapy, as it is called,

is not a cure, however. The virus remains, ready to flourish if the

drugs are withdrawn.

While most praise this new treatment, some researchers warn that

the cocktail could become this decade’s penicillin. When penicillin was

introduced, everyone was ecstatic about its effectiveness. However, over the years, the

microbes that penicillin targets mutated, producing “super germs” against which we have

Threats to Health 579

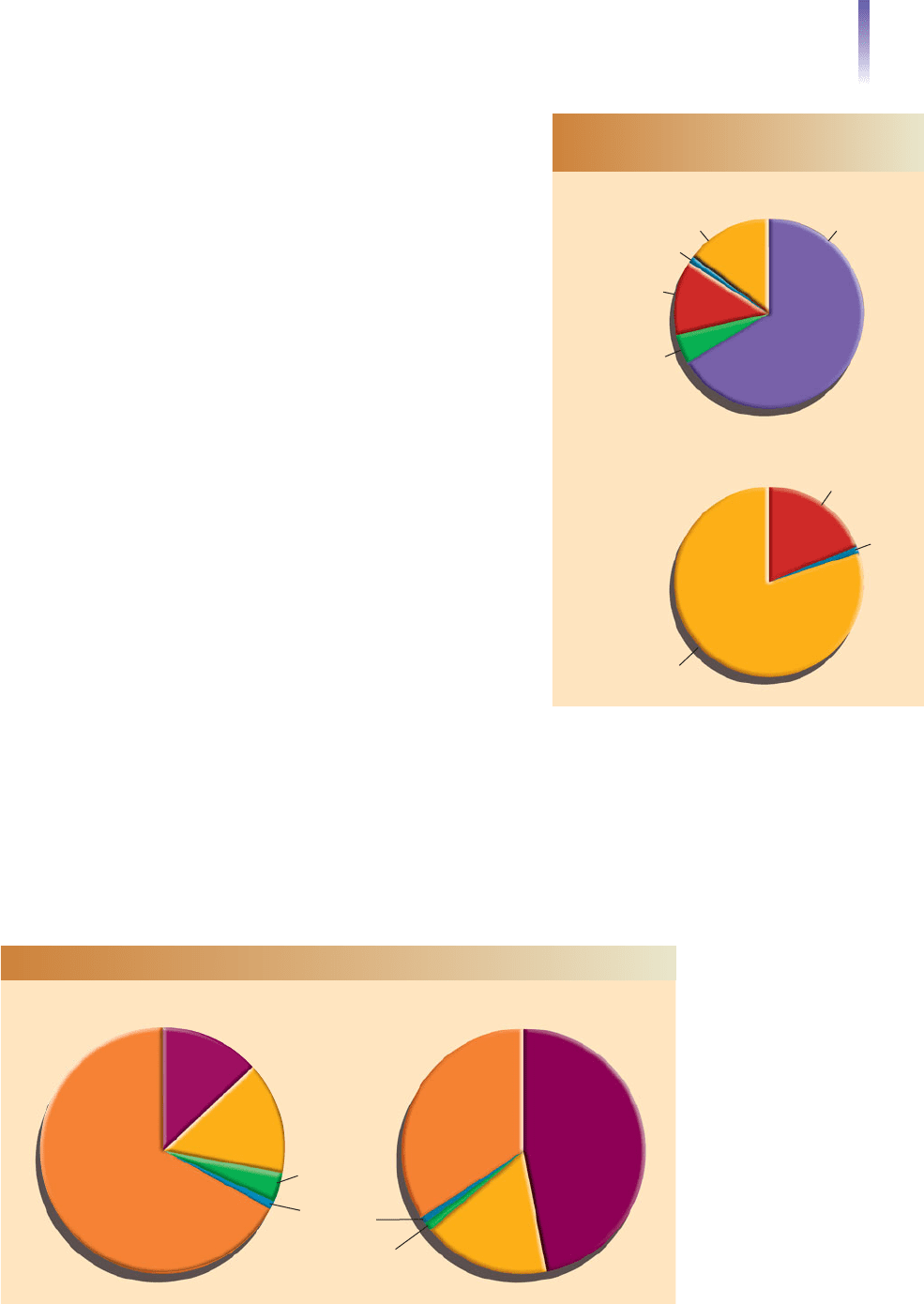

Females

80%

19%

Drug injection

Other

1%

Heterosexual sex

Males

67%

5%

12%

16%

Heterosexual sex

Other 1%

Homosexual

sex

Homosexual

sex and

drug injection

Drug injection

FIGURE 19.9 How Americans

Get AIDS

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

2008b.

Percentage of AIDS cases

Percentage of U.S. population

African

Americans

47%

Latinos

17%

Whites

34%

Whites

67%

African

Americans

13%

Latinos

15%

4%

Asian

Americans

Native

Americans

1%

Asian

Americans 1%

FIGURE 19.10 People Living with HIV/AIDS by Race–Ethnicity

Source: By the author. Based on Figure 12.5 of this text and Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention 2008b.

Note: “Other” includes unknown and blood

transfusion.

Note: To total 100 percent for the U.S. population and distribute the “claim two or more

race–ethnicities,” I rounded the totals for whites and African Americans up.

little protection. If this happens with AIDS, a tsunami of a “super-AIDS” virus could hit

the world with more fury than the first devastating wave.

Despite their frustrations, medical researchers remain hopeful that they will develop an

effective vaccine. If so, many millions of lives will be saved. If not, this disease will con-

tinue its global death march.

Weight: Too Much and Too Little

When a friend from Spain visited, I asked him to comment on the things that struck him

as different. He mentioned how surprised he was to see people living in metal houses. It

took me a moment to figure out what he meant, but then I understood: He had never seen

a mobile home. Then he added, “And there are so many fat Americans.”

Is this a valid perception, or just some twisted ethnocentric observation by a foreigner? The

statistics bear out his observation. Americans have added weight—and a lot of it. In 1980,

one of four Americans was overweight. By 1990, this percentage had jumped to one of

three. Now about two-thirds (67 percent) of Americans are overweight (Statistical Abstract

1998:Table 242; 2011:Table 207). We have become the fattest nation on earth.

Perhaps we should just shrug our shoulders and say, “So what?” Is obesity really anything

more than someone’s arbitrary idea of how much we should weigh? It turns out that obe-

sity has significant costs. The first is quite unexpected: Obese high school girls are less likely

to go to college (but there is no difference for overweight boys) (Crosnoe 2007). The sec-

ond is health: Obese people are more likely to come down with diabetes, kidney disease,

and some types of cancer (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009a). Obesity’s

health toll is high, accounting for about 112,000 deaths a year (Flegal et al. 2007).

A surprising side-effect of being overweight is that it helps some people live longer.

Evidently, being either seriously overweight (obese) or underweight increases people’s

chances of dying, but being a little overweight is good. No one yet knows the reason for

this, but some suggest that having a few extra pounds reduces bad cholesterol (Centers for

Disease Control 2005).

Alcohol and Nicotine

Many drugs, both legal and illegal, harm their users. Let’s examine some of the health

consequences of alcohol and nicotine, the two most frequently used legal drugs in the

United States.

Alcohol. Alcohol is the standard recreational drug of Americans. The average adult

American drinks 25 gallons of alcoholic beverages per year—about 22 gallons of beer,

3 gallons of wine, and almost 2 gallons of

whiskey, vodka, or other distilled spirits.

Beer is so popular that Americans drink

more of it than they do tea and fruit juices

combined (Statistical Abstract 2011:Table

211).

As you know, despite laws that ban alco-

hol consumption before the age of 21, un-

derage drinking is common. Table 19.1

shows that two-thirds of all high school stu-

dents drink alcohol during their senior year.

If getting drunk is the abuse of alcohol,

then, without doubt, among high school

students abusing alcohol is popular. As this

table also shows, almost half of all high

school seniors have been drunk during the

past year, with 28 percent getting drunk

during just the past month. From this table,

you can also see what other drugs high

school seniors use.

580 Chapter 19 MEDICINE AND HEALTH

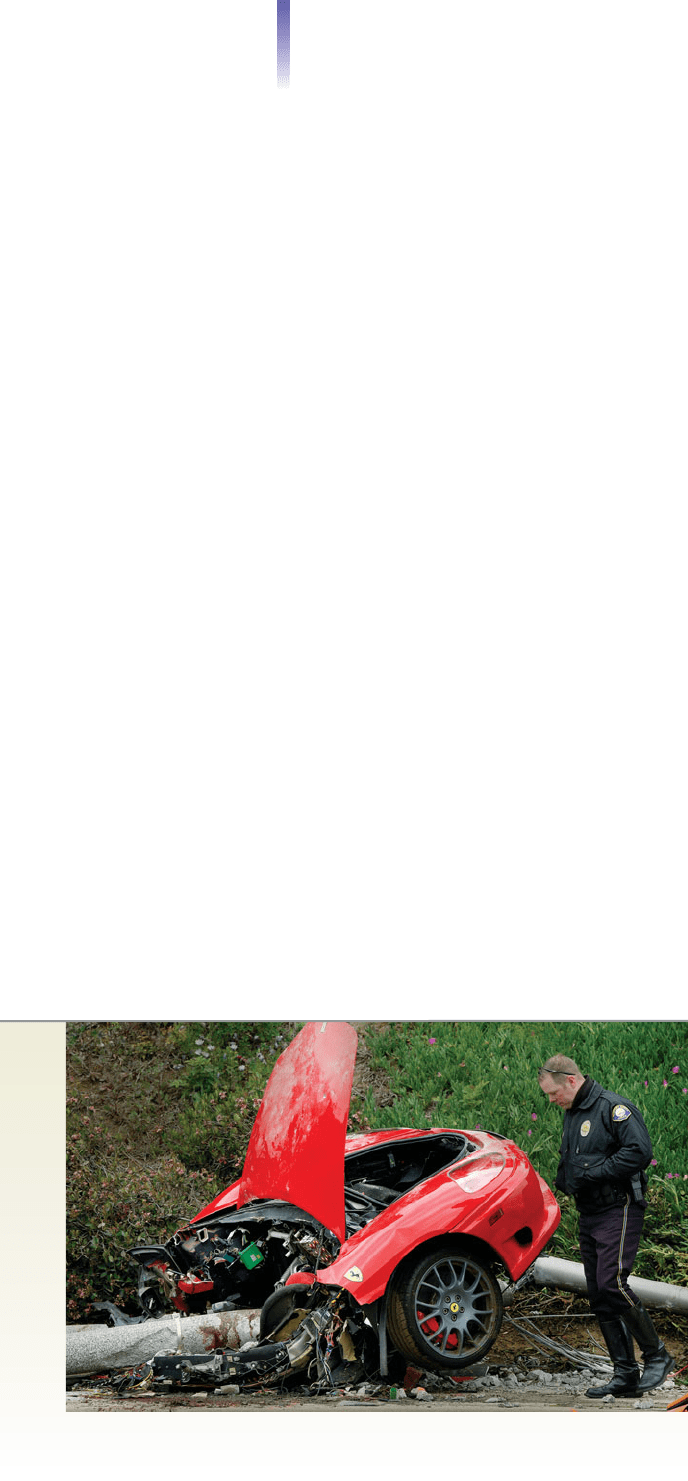

Everyone knows that drinking and driving don’t mix. Here’s what’s left of a Ferrari in

Newport Beach, California.The driver of the other car was arrested for drunk driving

and vehicular manslaughter.