Henslin James M. Sociology: A Down to Earth Approach

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

heavily influenced by religion, but no longer retains much of that influence. The

United States provides an example.

Despite attempts to reinterpret history, the Pilgrims and most of the founders of

the United States were highly religious people. The Pilgrims were even convinced

that God had guided them to found a new religious community whose members

would follow the Bible. Similarly, many of the framers of the U.S. Constitution felt

that God had guided them to develop a new form of government.

The clause in the Constitution that mandates the separation of church and state

was not an attempt to keep religion out of government, but a (successful) device to

avoid the establishment of a state religion like that in England. Here, people were to

have the freedom to worship as they wished. The assumption of the founders was

even more specific—that Protestantism represented the true religion.

The phrase in the Declaration of Independence, “All men are created equal,” refers

to a central belief in God as the creator of humanity. A member of the clergy opened

Congress with prayer. Many colonial laws were based on principles derived explic-

itly from the Old and New Testaments. In some colonies, blasphemy was a crime,

as was failing to observe the Sabbath. Similarly, sexual affairs were a crime; in some

places adultery carried the death penalty. Even public kissing between husband and

wife was considered an offense, punishable by placement in the public stocks

(Frumkin 1967). In other words, religion permeated U.S. culture. It was part and

parcel of how the colonists saw life. Their lives, laws, and other aspects of the cul-

ture reflected their religious beliefs.

As U.S. culture secularized, the influence of religion on public affairs diminished.

No longer are laws based on religious principles. It has even become illegal to post

the Ten Commandments in civic buildings. Overall, ideas of what is “generally good”

have replaced religion as an organizing principle for the culture.

Underlying the secularization of culture is modernization, a term that refers to a

society industrializing, urbanizing, developing mass education, and adopting sci-

ence and advanced technology. Science and advanced technology bring with them

a secular view of the world that begins to permeate society. They provide explana-

tions for many aspects of life that people traditionally attributed to God. As a con-

sequence, people come to depend much less on religion to explain life’s events. Birth

and death—and everything in between, from life’s problems to its joys—are attrib-

uted to natural causes. When a society has secularized thoroughly, even religious

leaders may turn to answers provided by biology, philosophy, psychology, sociology,

and so on.

Although the secularization of U.S. culture means that religion has become less

important in public life, personal religious involvement among Americans has not di-

minished. Rather, it has increased (Finke and Stark 1992). About 86 percent believe

there is a God, and 81 percent believe there is a

heaven. Not only do 63 percent claim membership in

a church or synagogue, but, as we saw, on any given

weekend somewhere between 30 and 42 percent of all

Americans attend a worship service (Gallup 1990,

2008b).

Table 18.2 underscores the paradox. While the cul-

ture has secularized, church membership has increased.

The proportion of Americans who belong to a church

or synagogue is now about three and a half times higher

than it was when the country was founded. As you can

see, membership peaked in 1975. Church member-

ship, of course, is only a rough indicator of how signif-

icant religion is in people’s lives. Some church

members are not particularly religious, while many in-

tensely religious people—Lincoln, for one—never

joined a church.

Americans Who Belong to a Church or Synagogue

Percentage Who Claim

Year Membership

1776 17%

1860 37%

1890 45%

1926 58%

1975 71%

2000 68%

2007 62%

TABLE 18.2 Growth in Religious Membership

Sources: Finke and Stark 1992; Statistical Abstract of the United States 2002:Table 64;

Gallup Poll 2007b.

Note: The sources do not contain data on mosque membership.

Religion in the United States 551

The Future of Religion

Religion thrives in the most advanced scientific nations—and, as officials of Soviet

Russia were disheartened to learn—in even the most ideologically hostile climate.

Although the Soviet authorities threw believers into prison, people continued to

practice their religions. Humans are inquiring creatures. As they reflect on life, they

ask, What is the purpose of it all? Why are we born? Is there an afterlife? If so, where

are we going? Out of these concerns arises this question: If there is a God, what

does God want of us in this life? Does God have a preference about how we should

live?

Science, including sociology, cannot answer such questions. By its very nature, science

cannot tell us about four main concerns that many people have:

1. The existence of God. About this, science has nothing to say. No test tube has either

isolated God or refuted God’s existence.

2. The purpose of life. Although science can provide a definition of life and describe

the characteristics of living organisms, it has nothing to say about ultimate purpose.

3. An afterlife. Science can offer no information on this at all, for it has no tests to

prove or disprove a “hereafter.”

4. Morality. Science can demonstrate the consequences of behavior, but not the

moral superiority of one action compared with another. This means that science

cannot even prove that loving your family and neighbor is superior to hurting

and killing them. Science can describe death and measure consequences, but it

cannot determine the moral superiority of any action, even in such an extreme

example.

There is no doubt that religion will last as long as humanity lasts, for what could re-

place it? And if something did, and answered such questions, would it not be religion

under a different name?

To close this chapter, let’s try to glimpse the cutting edge of religious change.

A basic principle of symbolic

interactionism is that meaning is

not inherent in an object or event,

but is determined by people as

they interpret the object or event.

Does this dinosaur skeleton

“prove” evolution? Does it

“disprove” creation? Such “proof”

and “disproof ” lie in the eye of the

beholder, based on the

background assumptions by which

it is interpreted.

552 Chapter 18 RELIGION

The Future of Religion 553

MASS MEDIA In

SOCIAL LIFE

God on the Net:The Online

Marketing of Religion

You want to pray right there at the Holy Land, but

you can’t leave home? No problem. Buy our special

telephone card—now available at your local 7-11.

Just record your prayer, and we’ll broadcast it via the

Internet at the site you choose. Press 1 for the holy

site of Jerusalem, press 2 for the holy site of the Sea

of Galilee, press 3 for the birthplace of Jesus, press 4

for . . . (Rhoads 2007)

This service is offered by a company in Israel. No

discrimination. Open to Jews and Christians alike. Maybe

with expansion plans for Muslims. Maybe to anyone, as

long as they can pay $10 for a two-minute card.

You left India and now live in Kansas but you want

to pray in Chennai? No problem. Order your pujas

(prayers), and we’ll have a priest say them in the

temple of your choice. Just click how many you want.

Food offerings for Vishnu included in the price. All

major credit cards accepted (K. Sullivan 2007).

Erin Polzin, a 20-year-old college student, listens

to a Lutheran worship service on the radio, con-

fesses online, and uses PayPal to tithe.“I don’t like

getting up early,” she says.“This is like going to

church without really having to” (Bernstein 2003).

You can go to church in your pajamas, and you don’t

even have to comb your hair.

Muslims in France download sermons and join an in-

visible community of worshippers at virtual mosques.

Jews in Sweden type messages that fellow believers in

Jerusalem download and insert in the Western Wall.

Christians in the United States make digital donations

to the Crystal Cathedral. Buddhists in Japan seek en-

lightenment online. The Internet helps to level the pul-

pit: On the Net, the leader of a pagan group can

compete directly with the Pope.

There are also virtual church services. Just choose an

avatar, and you can walk around the virtual church. You

can sing, kneel, pray, and listen to virtual sermons.You

can talk to other avatars if you get bored (Feder 2004).

And, of course, you can use your credit card—a real

one, not the virtual kind.

The Internet is also making it harder for religious

groups to punish their rebels. Jacques Gaillot is a French

Roman Catholic bishop who marches in public demon-

strations for the poor. He also takes theological posi-

tions that upset the church hierarchy: The clergy should

marry, women should be ordained, and homosexual

partnerships should be blessed. Pope John Paul II took

Gaillot’s diocese away from him and gave him a nonex-

istent diocese in the Saharan desert of North Africa.

This strategy used to work well to silence dissidents,

but it didn’t stop Gaillot. He uses the Internet to publi-

cize his views (Huffstutter 1998; Williams 2003).

So does the Vatican at its Web site, which also offers

virtual tours of its art galleries. But the real sign of

changing times occurred in 2009 when the pope

launched his own YouTube channel (Winfield 2009).

Some say that the Net has put us on the verge of a

religious reformation as big as the one set off by Guten-

berg’s invention of the printing press. This sounds like

an exaggeration, but perhaps it is true.We’ll see.

For Your Consideration

We are gazing into the future. How do you think that

the Internet might change religion? How can it replace

the warm embrace of fellow believers? Do you think it

can it bring comfort to someone who is grieving for a

loved one?

Some people have begun to “attend” church as avatars.

Percentage of Americans claiming

membership in a church or synagogue

17 76

17

NOW

62

%%

554 Chapter 18 RELIGION

SUMMARY and REVIEW

What Is Religion?

Durkheim identified three essential characteristics of reli-

gion: beliefs that set the sacred apart from the profane,

rituals, and a moral community (a church). Pp. 524–525.

The Functionalist Perspective

What are the functions and dysfunctions of religion?

Among the functions of religion are answering questions

about ultimate meaning; providing emotional comfort, so-

cial solidarity, guidelines for everyday life, social control, help

in adapting to new situations, support for the government;

and fostering social change. Nonreligious groups or activities

that provide these functions are called functional equiva-

lents of religion. Among the dysfunctions of religion are re-

ligious persecution and war and terrorism. Pp. 525–528.

The Symbolic Interactionist Perspective

What aspects of religion do symbolic

interactionists study?

Symbolic interactionists focus on the meanings of religion

for its followers. They examine religious symbols, rituals,

beliefs, religious experiences, and the sense of commu-

nity that religion provides. Pp. 528–531.

The Conflict Perspective

What aspects of religion do conflict theorists study?

Conflict theorists examine the relationship of religion to

social inequalities, especially how religion reinforces a so-

ciety’s stratification system. Pp. 531–534.

Religion and the Spirit of Capitalism

What does the spirit of capitalism have

to do with religion?

Max Weber saw religion as a primary source of social

change. He analyzed how Calvinism gave rise to the

Protestant ethic, which stimulated what he called the

spirit of capitalism. The result was capitalism, which

transformed society. Pp. 534–535.

The World’s Major Religions

What are the world’s major religions?

Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, all monotheistic reli-

gions, can be traced to the same Old Testament roots. Hin-

duism, the chief religion of India, has no specific founder,

but Judaism (Abraham), Christianity (Jesus), Islam

(Muhammad), Buddhism (Gautama), and Confucianism

(K’ung Fu-tsu) do. Specific teachings and history of these

religions are reviewed in the text. Pp. 536–540.

Types of Religious Groups

What types of religious groups are there?

Sociologists divide religious groups into cults, sects,

churches, and ecclesias. All religions began as cults. Those

that survive tend to develop into sects and eventually into

churches. Sects, often led by charismatic leaders, are

unstable. Some are perceived as threats and are perse-

cuted by the state. Ecclesias, or state religions, are rare.

Pp. 541–544.

Religion in the United States

What are the main characteristics of religion

in the United States?

Membership varies by social class and race–ethnicity. The

major characteristics are diversity, pluralism and freedom,

competition, commitment, toleration, a fundamentalist

revival, and the electronic church. Pp. 545–548.

What is the connection between secularization

of religion and the splintering of churches?

Secularization of religion, a change in a religion’s focus

from spiritual matters to concerns of “this world,” is the

key to understanding why churches divide. Basically, as a

By the Numbers: Then and Now

Summary and Review 555

cult or sect changes to accommodate its members’ upward

social class mobility, it changes into a church. Left dissat-

isfied are members who are not upwardly mobile. They

tend to splinter off and form a new cult or sect, and the

cycle repeats itself. Cultures permeated by religion also

secularize. This, too, leaves many people dissatisfied and

promotes social change. Pp. 549–551.

The Future of Religion

Although industrialization led to the secularization of

culture, this did not spell the end of religion, as many so-

cial analysts assumed it would. Because science cannot an-

swer questions about ultimate meaning, the existence of

God or an afterlife, or provide guidelines for morality, the

need for religion will remain. In any foreseeable future,

religion will prosper. The Internet is likely to have far-

reaching consequences on religion. Pp. 552–553.

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT Chapter 18

1. Since 9/11, many people have wondered how anyone can

use religion to defend or promote terrorism. How does the

Down-to-Earth Sociology box on terrorism and the mind of

God on page 529 help to answer this question? How do

the analyses of groupthink in Chapter 6 (pages 169–170)

and dehumanization in Chapter 15 (pages 450–452) fit into

your analysis?

2. How has secularization affected religion and culture in the

United States (or of your country of birth)?

3. Why is religion likely to remain a strong feature of U.S. life—

and remain strong in people’s lives around the globe?

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

What can you find in MySocLab? www.mysoclab.com

• Complete Ebook

• Practice Tests and Video and Audio activities

• Mapping and Data Analysis exercises

• Sociology in the News

• Classic Readings in Sociology

• Research and Writing advice

Where Can I Read More on This Topic?

Suggested readings for this chapter are listed at the back of this book.

Medicine and Health

19

Chapter

decided that it was not enough to just study

the homeless—I had to help them. I learned that

a homeless shelter in St. Louis, just across the river from

where I was teaching, was going to help poor people save on

utilities by installing free wood stoves in their homes. When their

utilities are cut off, the next

step is eviction and being

forced onto the streets. It

wasn’t exactly applied sociol-

ogy, but I volunteered.

I was a little anxious

about the coming training session on how to install stoves, as I had

never done anything like this. Sociology hadn’t trained me to be

“handy with my hands,” but with the encouragement of a friend,

I decided to participate. As I entered the homeless shelter on that

Saturday morning, I found the building in semidarkness. “They

must be saving on electricity,” I thought. Then I was greeted with

an unnerving scene. Two police officers were chasing a naked man,

who was running through the halls. They caught him. I watched as

the elderly man, looking confused, struggled to put on his clothing.

From the police, I learned that this man had ripped the wires out of

the shelter’s main electrical box; that was why there were no lights on.

I asked the officers where they were going to take the man, and

they replied, “To Malcolm Bliss” (the state hospital). When I said,

“I guess he’ll be in there for quite a while,” they replied, “Probably

just a day or two. We picked him up last week—he was crawling

under cars at a traffic light—and they let him out in two days.”

The police then explained that the man must be a danger to

himself or to others to be admitted as a long-term patient. Visualiz-

ing this old man crawling under stopped cars at an intersection,

and considering how he had risked electrocution by ripping out the

electrical wires with his bare hands, I marveled at the definition of

“danger” that the psychiatrists must be using.

I

He was crawling under cars

at a traffic light—and they

let him out in two days.

557

Utah

Sociology and the Study

of Medicine and Health

This incident points to a severe problem in the delivery of medical care in the United

States. In this chapter, we will examine why the poor often receive second-rate medical care

and, in some instances, abysmal treatment. We’ll also look at how skyrocketing costs have

created ethical dilemmas such as the discharge of patients from hospitals before they are well

and the potential rationing of medical care.

As we consider these issues, the role of sociology in studying medicine—a society’s stan-

dard ways of dealing with illness and injury—will become apparent. For example, because

medicine in the United States is a profession, a bureaucracy, and a big business, sociologists

study how it is influenced by self-regulation, the bureaucratic structure, and the profit mo-

tive. Sociologists also study how illness and health are much more than biological matters—

how, for example, they are related to cultural beliefs, lifestyle, and social class. Because of

these emphases, the sociology of medicine is one of the applied fields of sociology. Many

medical schools and even hospitals have sociologists on their staffs.

The Symbolic Interactionist Perspective

Let’s begin, then, by examining how culture influences health and illness. This takes us

to the heart of the symbolic interactionist perspective.

The Role of Culture in Defining Health and Illness

Suppose that one morning you look in the mirror and you see strange blotches covering

your face and chest. Hoping against hope that it is not serious, you rush to a doctor. If the

doctor said that you had “dyschromic spirochetosis,” your fears would be confirmed.

Now, wouldn’t everyone around the world draw the conclusion that your spots are

symptoms of a disease? No, not everybody. In one South American tribe, this skin con-

dition is so common that the few individuals who aren’t spotted are seen as the un-

healthy ones. They are even excluded from marriage because they are “sick” (Ackernecht

1947; Zola 1983).

Consider mental “illness” and mental “health.” People aren’t automatically “crazy” be-

cause they do certain things. Rather, they are defined as “crazy” or “normal” according to

cultural guidelines. If an American talks aloud to spirits that no one else can see or hear,

he or she is likely to be defined as insane—and, for everyone’s good, locked up in a

mental hospital. In some tribal societies, in contrast, someone who talks to invis-

ible spirits might be honored for being in close contact with the spiritual world—

and, for everyone’s good, be declared a shaman, or spiritual intermediary. The

shaman would then diagnose and treat medical problems.

“Sickness” and “health,” then, are not absolutes, as we might suppose. Rather,

they are matters of cultural definition. Around the world, each culture provides

guidelines that its people use to determine whether they are “healthy” or “sick.”

The Components of Health

Back in 1941, international “health experts” identified three components of

health: physical, mental, and social (World Health Organization 1946). They

missed the focus of our previous chapter, however, and I have added a spir-

itual component to Figure 19.1. Even the dimensions of health, then, are

subject to debate.

Even if we were to agree on the components of health, we would still

be left with the question of what makes someone physically, mentally, so-

cially, or spiritually healthy. Again, as symbolic interactionists stress, these

558 Chapter 19 MEDICINE AND HEALTH

medicine one of the social

institutions that sociologists

study; a society’s organized

ways of dealing with sickness

and injury

shaman the healing specialist

of a tribe who attempts to

control the spirits thought to

cause a disease or injury; com-

monly called a witch doctor

health a human condition

measured by four components:

physical, mental, social, and

spiritual

We define health and illness

according to our culture. If

almost everyone in a village had

this skin disease, the villagers

might consider it normal—and

those without it the unhealthy

ones. I photographed this infant

in a jungle village in Orissa, India,

so remote that it could

be reached only by

following a foot

path.

are not objective matters. Rather, what is considered “health” or “illness” varies from culture

to culture and, in a pluralistic society, even from group to group.

As with religion in the previous chapter, then, the concern of sociologists is not to de-

fine “true” health or “true” illness. Instead, it is to analyze how people’s experiences affect

their health, how people’s ideas about health and illness affect their lives, and even how

people determine that they are sick.

The Functionalist Perspective

Functionalists begin with an obvious point: If society is to function well, its people need

to be healthy enough to perform their normal roles. This means that societies must set up

ways to control sickness. One way they do this is to develop a system of medical care.

Another way is to make rules that help keep too many people from “being sick.” Let’s look

at how this works.

The Sick Role

Do you remember when your throat began to hurt, and when your mom or dad took your

temperature the thermometer registered 102°F? Your parents took you to the doctor, and

despite your protests that tomorrow was the first day of summer vacation (or some other

important event), you had to spend the next three days in bed taking medicine.

Your parents forced you to play what sociologists call the “sick role.” What do they mean

by this term?

Elements of the Sick Role. Talcott Parsons, the functionalist who first analyzed the sick

role, pointed out that it has four elements—you are not held responsible for being sick,

you are exempt from normal responsibilities, you don’t like the role, and you will get com-

petent help so you can return to your routines. People who seek approved help are given

sympathy and encouragement; those who do not are given the cold shoulder. People who

don’t get competent help are considered responsible for being sick, are refused the right

to claim sympathy from others, and are denied permission to be excused from their nor-

mal routines. They are considered to be wrongfully claiming the sick role.

Ambiguity in the Sick Role. Instead of a fever of 102°F, suppose that the thermometer

registers 99.5°F. Do you then “become” sick—or not? That is, do you decide to claim the

sick role? Because most instances of illness are not as clear-cut as, say, a limb fracture, de-

cisions to claim the sick role often are based more on social considerations than on phys-

ical conditions. Let’s also suppose that you are facing a midterm, you are unprepared for

it, and you are allowed to make up the test if you are ill. The more you think about the

test, the worse you are likely to feel—which makes the need to claim the sick role seem

more legitimate. Now assume that the thermometer still shows 99.5, but you have no

test and your friends are coming over to take you out to celebrate your twenty-first birth-

day. You are not likely to play the sick role. Note that in both cases your physical condi-

tion is the same.

Gatekeepers to the Sick Role. For children, parents are the primary gatekeepers to the

sick role. That is, parents decide whether children’s symptoms are sufficient to legit-

imize their claim that they are sick. Before parents call the school to excuse a child

from class, they decide whether the child is faking or has genuine symptoms. If they

determine that the symptoms are real, then they decide whether the symptoms are se-

rious enough to keep the child home from school or even severe enough to take the

child to a doctor. For adults, the gatekeepers to the sick role are physicians. Adults can

bypass the gatekeeper for short periods, but employers will eventually insist on a “doc-

tor’s excuse.” This can come in such forms as a “doctor’s appointment” or insurance

forms signed by the doctor. In sociological terms, these are ways of getting permission

to play the sick role.

The Functionalist Perspective 559

Health

Excellent Functioning

Poor Functioning

Illness

P

H

Y

S

I

C

A

M

E

N

T

A

L

S

O

C

I

A

L

L

S

P

I

R

I

T

U

A

L

FIGURE 19.1 A

Continuum of Health

and Illness

sick role a social role that ex-

cuses people from normal obli-

gations because they are sick

or injured, while at the same

time expecting them to seek

competent help and cooperate

in getting well

Gender Differences in the Sick Role. Women are more willing than men to claim the

sick role when they don’t feel well. They go to doctors more frequently than men, and they

are hospitalized more often than men (Statistical Abstract 2011:Tables 162, 165, 172).

Apparently, the sick role does not match the macho image that most boys and men try to

project. Most men try to follow the cultural ideal that they should be strong, keep pain

to themselves, and “tough it out.” The woman’s model, in contrast, is more likely to in-

volve sharing feelings and seeking help from others, characteristics that are compatible

with the sick role.

The Conflict Perspective

As we stressed in earlier chapters, the primary focus of the conflict perspective is people’s

struggle over scarce resources. Health care is one of those resources. Let’s first take a global

perspective on medical care and then, turning our attention to the United States, we will

analyze how one group secured a monopoly on U.S. health care.

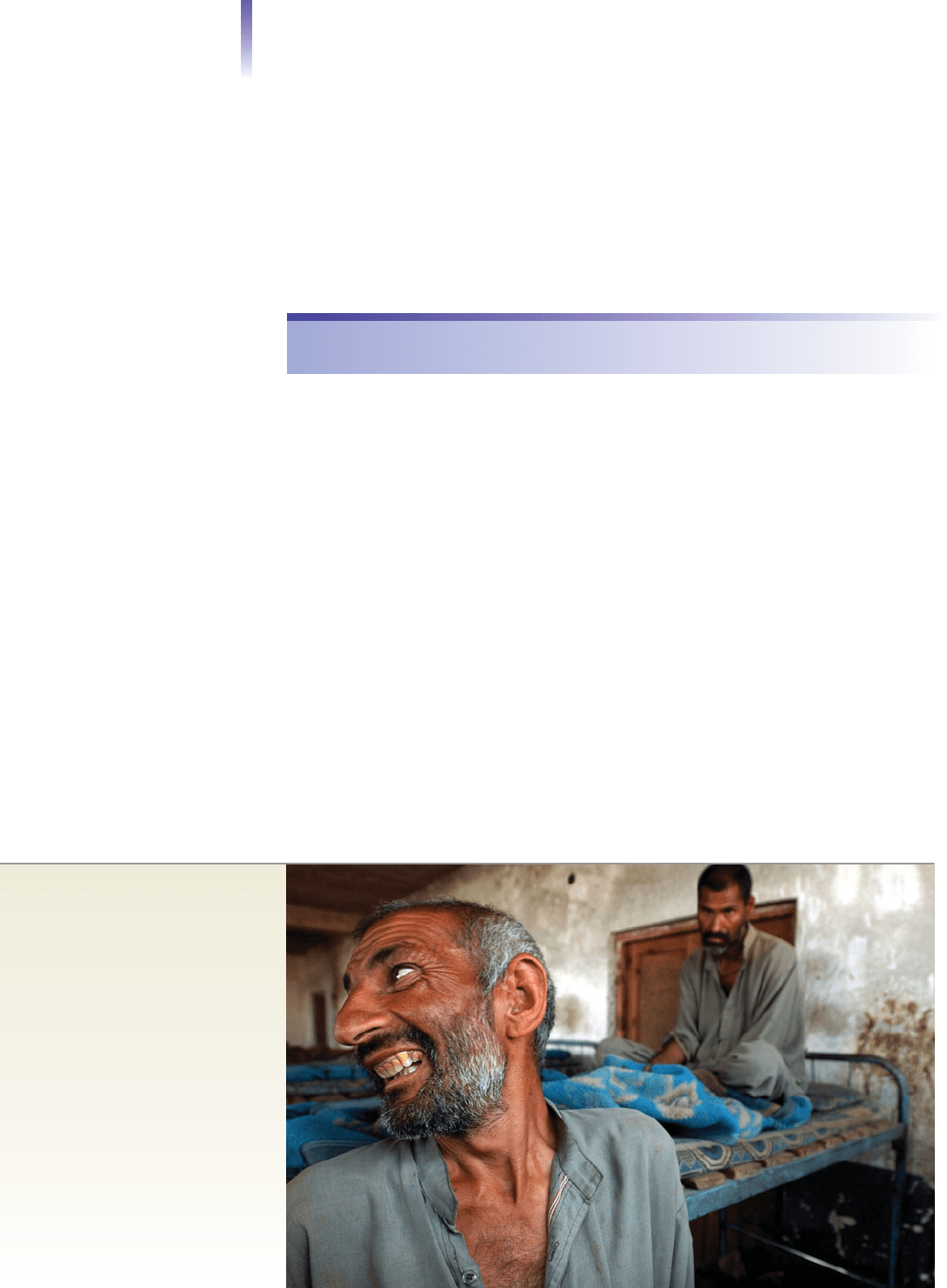

Effects of Global Stratification on Health Care

In Chapter 9 (pages 252–253), we saw how the first nations to industrialize obtained the

economic and military power that brought them riches and allowed them to dominate

other nations. This eventually led to a global stratification of medical care, starkly evi-

dent in the photo below. For example, open heart surgery has become routine in the Most

Industrialized Nations. The Least Industrialized Nations, in contrast, cannot afford the

technology that open heart surgery requires. So it is with AIDS. In the United States and

other rich nations, costly medicines have extended the lives of those who suffer from

AIDS. Most people with AIDS in the Least Industrialized Nations can’t afford these med-

icines. For them, AIDS is a death sentence.

Life expectancy and infant mortality rates also tell the story. Most people in the indus-

trialized world can expect to live to about age 75, but most people in Afghanistan, Nige-

ria, and South Africa don’t even make it to 50. Look at Figure 19.2 on the next page,

which shows countries in which fewer than 7 of every 1,000 babies die before they are a

560 Chapter 19 MEDICINE AND HEALTH

Global stratification in health

care is starkly evident in this

photo of patients in the

Marastoon mental hospital in

West Kabul, Afghanistan.