Heine Bernd, Nurse Derek. A Linguistic Geography of Africa

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

to speak, sandwiched between the Atlantic Ocean and the Congo Basin in the

south and the Sahara and Sahel in the north, and spans the continent from the

Atlantic Ocean in the west to the escarpment of the Ethiopian Plateau in the east.

To a considerable extent, there are also linguistic correlates of the above

external boundaries. That is, the area excludes regions which are more

homogeneous in linguistic-genealogical terms, namely the Saharan spread

zone in the north covered today by Berber, Saharan, and Arabic; the spread

zone in the south colonized by Narrow Bantu; and finally the Ethiopian Plateau

in the east dominated by Cushitic and Ethio-Semitic (see chapter 7; see Nichols

1992 for the general concept of a ‘‘spread zone’’).

Regarding the internal profile of the area, o ne needs to distinguish between

different types of languages and language groups constituting it. That is, not

all linguistic lineages concerned are involved to the same degree in certain

distribution patterns of linguistic features.

The core of the area is formed by the following language families: Mande,

Kru, Gur, Kwa, Benue-Congo (excluding Narrow Bantu), Adamawa-Ubangi,

Bongo-Bagirmi,

1

and Moru-Ma ngbetu. The two easternmost families of

Niger-Congo, Benue-Congo and Adamawa-Ubangi, as well as the two Central

Sudanic families, Bongo-Bagirmi and Moru-Ma ngbetu, will be shown to hold

a particularly prominent position in the core group and form again a compact

geographical block.

Some lineages, which in geographical terms are all peripheral but still

adjacent to the core, display an ambiguous behavior regarding linguistic

commonalities with this area. These lineages are Atlantic, Dogon, Songhay,

Chadic, Ijoid, Narrow Bantu, and Nilotic.

The above remarks suggest that genealogical language groups to be

considered in this chapter are usually low-level units, called here ‘‘families,’’

ignoring the four super-groups proposed by Greenberg (1963). Reasons for

taking such smaller genealogical units as the reference of continental sampling

will be postponed until section 5.4.2. Suffice it to say here that my approach has

the advantage that a greater variety of languages will have to be included and

no relevant genealogical group for which data are available is unduly omitted.

Clearly, if this breakdown were to be transferred into a genealogical clas-

sification this would be a far more splitting one. The present schema, which

does not refer to groups like Khoisan, Nilo-Saharan, and Niger-Kordofanian,

2

should, however, not be viewed as an alternative classification proposal; to

develop such a classification woul d be an endeavor in its own right. Low-level

sampling is warranted by the particular topic of thi s chapter, which must

consider the possibility that certain types of linguistic commonalities, when

involving genealogical entities that are not yet based on solid evidence, may

well have an explanation other than common inheritance, inter alia, one in

terms of areal contact.

Tom Gu

¨

ldemann152

5.2 The linguistic features

The following section will discuss the linguistic features which are thought to

be relevant for establishing the linguistic area at issue. The methodology has

been to survey the presence/absence of a certain candidate feature in language

families across the entire African continent – this mostly in two steps: first,

relevant sources on a given feature have been consulted in order to assemble a

basic list of languages and families possessing it; when necessary, lineages not

mentioned there have been checked in a second phase as to the presence or

absence of the feature. The information here is based on group surveys;

3

my

own knowledge, particularly o f the various Khoisan groups; and last but not

least personal communication from family specialists.

4

Sometimes, descrip-

tions of individual languages have been consulted too.

A closer look at the languages and language groups surveyed will reveal that

several African lineages which would have to be considered according to the

family level chosen for this investigatio n are not included, generally or for

individual features. This is due to the lack of appropriate, relia ble data. Such

omissions concern in particular Kordofanian and a number of poorly docu-

mented groups commonly subsum ed under Nilo-Saharan. In geographical

terms, these languages cluster in three areas in the eastern domain of the

relevant part of Africa (indicated in the accompanying maps by means

of dotted areas), called here from east to west (a) ‘‘Ethiopian escarpment,’’

(b) ‘‘Nuba Mountains,’’ and (c) ‘‘Southwest Sudan border belt.’’ These are

‘‘fragmentation’’ zones in the sense that they display a considerable amount of

genealogical diversity.

5

In ascertaining the distribution of a feature within a family, I make a basic

distinction between three degrees of frequency, namely (a) absent, (b) present,

and (c) frequent. The empirical limitations of the available data affect what is

behind these three classificatory values. The value ‘‘frequent’’ is the most

straightforward in the sense that it is intended exclusively to mean a fairly

homogeneous distribution and frequent presence of the feature across the relevant

group. When assigning to a family the value ‘‘present,’’ this does not always

imply a frequency evaluation, because the available data may be insufficient;

usually it means that the feature is an occasional or even rather isolated phe-

nomenon in the family, but it could also be more frequent. Finally, the value

‘‘absent’’ stands in principle for the feature’s absence in a family; but sometimes

this is merely inferred from the fact that I did not come across a relevant language.

Given the great nu mber of African languages as well as their overall poor

state of description, it is clear that the data achieved in the analytical procedure

described above cannot be claimed to be complete. Hence, the distributional

patterns arising here are to a certain extent preliminary; at the same time, they

seem to be robust enough to be discussed from a wider African perspective.

The Macro-Sudan belt 153

Each feature survey is summarized in a table where the affected families

(mostly followed by a letter code) and/or languages are listed. The above three-

waysplitisrepresentedbysimplyrecordingthevalues‘‘present’’ and ‘‘frequent.’’

Hence, lineages which do not appear in these tables are assumed to lack the

property entirely. Where the value ‘‘frequent’’ is identified for a family, this is

marked by a grey cell in the table column ‘‘Language or group’’ instead of

giving the numerous possible attestations for such groups. In all other cases,

the individual languages which possess the respective feature, according to

reported data, appear in the relevant column.

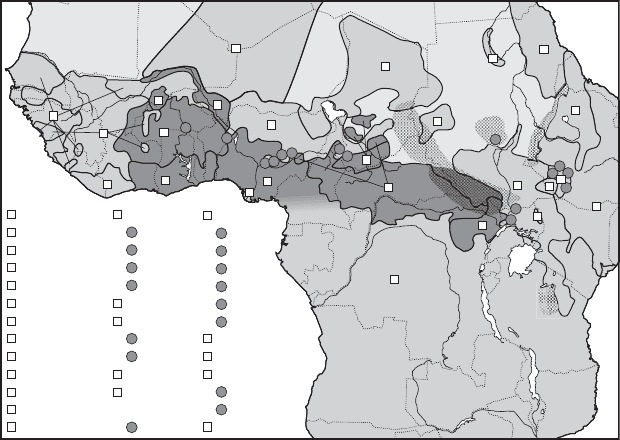

A survey is also accompanied by a map showing the rough distribution of

major language families in the wider area (smaller enclaves of a family are

indicated by a line connecting them with the respective letter code). The

families which have a given feature frequently are marked as a whole by dark

grey. While this may represent an oversimplification of a potentially more

heterogeneous picture in the family, I did not find any other solution that would

not have inhibited the map’s usability. The special pattern within Benue-

Congo, namely that a feature is present except in most of Narrow Bantu, is

reflected by the fading out of the grey shading. Where the occurrence of a

feature is restricted to a more moderate number of languages, I indicate this

both in the map and the legend by a numbered d ot, also in dark grey. Hence,

the continental distribution of a feature will be graphically discernible from the

contrast of light vs. dark grey.

5.2.1 Logophoricity

Gu

¨

ldemann (2003a) is an investigation of the distribution of so-called

‘‘logophoric’’ markers in Africa. They are defined there as grammatical

devices that indicate in non-direct reported discourse the corefer ence of a

quote-internal nominal to its source, the speaker, who is mostly encoded in the

construction accompa nying/signaling the presence of the quote. Logophoric

markers are mostly pronouns which contrast with other unmarked pronouns

indicating non-coreference, as in (1) from Kera (C hadic).

(1) a. w

@ mı

´

ntı

´

to

´

ko

´

ore

´

vs.

3M.Sx QUOT 3M.S.LOGx go.away

b. w

@ mı

´

ntı

´

w@ ko

´

ore

´

3M.Sx QUOT 3M.Sy go.away

‘Er sagte, daß er weggehe’ [he said he would go] (Ebert 1979: 260)

An essential criterion for diagnosing the presence of grammaticalized

logophoricicty in a language is that the marking device is regular or even

obligatory in this context; it does not mean that it is only used in this function,

in other words, that it is a dedicated marker. On this basis, the distribution of

Tom Gu

¨

ldemann154

logophoricity acro ss African languages and lineages has been determined as

far as possible. The results are given in table 5.1.

That logophoricity occurs only in a few languages or just one sub-branch of a

family holds, according to the available data, for Nilotic, Omotic, Chadic, and

Mande. The other pattern of logophoricity distribution, according to which the

feature is evenly distributed in the group, seems to apply to Songhay (Jeffrey

Heath, p.c.) and Dogon (Culy & Kodio 1995), but the information does not yet

allow a conclusive assessment. Two far larger groups can be identified with

more confidence as lineages rich in logophoric languages: Central Sudanic (both

member families affected) and Narrow Niger-Congo (all member families but

Kru being affected). An important observation, to come up also in later sections,

is that a considerable portion of Benue-Congo – a member of Narrow Niger-

Congo – does not show the feature, namely the great majority of Narrow Bantu

languages outside west-central Africa. These differ in this respect from the many

non-Bantu Bantoid languages, their closest relatives, and even some Bantu

languages in west-central Africa displaying logophoricity.

Table 5.1 Logophoricity across African lineages

Family Stock

Language or

group (branch) Area

Bongo-Bagirmi A Central Sudanic

Moru-Mangbetu B Central Sudanic

Adamawa-Ubangi C N. Niger-Congo

Benue-Congo D N. Niger-Congo except most of

Narrow Bantu

Kwa E N. Niger-Congo

Gur F N. Niger-Congo

Dogon G – Niger bend

Songhay H – Koyra Chiini, Niger bend

Koyraboro Senni

Omotic O Afroasiatic Gimira, Male, Southwest Ethiopia

Wolaitta,

Kafi-noono

Nilotic Q Eastern Acholi, Lango North Uganda

Sudanic (West)

Kado – Krongo Nuba Mountains

Chadic T Afroasiatic Mwaghavul, North Nigeria;

Angas, Southeast Chad

Tangale, Pero

(West); Kera, Lele

(East)

Mande W – Bisa, Boko-Busa

(East)

Ghana, Burkina Faso,

Benin, Nigeria

The Macro-Sudan belt 155

The geographical pattern in map 5.1 shows that African languages with a

logophoric system are concentrated in a fairly compact, broad belt stretching

from northern Uganda in the east up to the Niger River in the west. Only

Krongo in the Nuba Mountains and a few Omotic languages in Ethiopia are not

directly integrated in this area, but are still close to it. It must be stressed that

this area is not defined by any com plete coverage by the feature at issue, b ut

rather by its fairly consistent non-occurrence outside it.

In some lineages, member languages only possess logophoric marking when

they are located in or close to the area, but lack it when they are farther away.

This holds for Narrow Bantu, Chadic, Niloti c, and Mande; this can be dis-

cerned from the relevant languages listed in map 5.1 vis-a

`

-vis the general

position of their respective family. For Chadic, Frajzyngier (1985) has argued

that logophoricity cannot be reconstructed to the proto-language and is better

accounted for by contact-induced interference from non-Chadic languages.

The same interpretation is likely for Mande and Nilotic.

5.2.2 Labial-velar consonants

Another feature relevant for the discussion is the presence of labial-velar con-

sonants. Maddieson’s(1984: 215–16) data on a world sample of 317 languages

showed that these sounds are virtually restricted to Africa; outside this continent,

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Kado

Krongo

Mande

14

Bisa

15

Boko-Busa

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

X

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

J

K

L

M

Chadic

8

Mwaghavul

9

Angas

10

Tangale

11

Pero

12

Kera

13

Lele

T

U

V

W

X

M

Moru-Mangbetu

Bongo-Bagirmi

Adamawa-Ubangi

Benue-Congo

Kwa

Gur

Dogon

Songhai

Berber

Saharan

Nubian

Cushitic

N

Ethio-Semitic

Nilotic

Omotic

Acholi

Lango

Bench

Male

Wolaitta

Kaficho

O

P

Q

R

S

Surmic

Kuliak

Furan

Ijoid

Kru

Atlantic

1

3

2

4

5

6

7

D

Bantu

Map 5.1 Logophoricity across African lineages

Tom Gu

¨

ldemann156

this survey yielded only Iai from Austronesian as having voiced /gb/. Maddieson

(2005) presents a similar picture except that there are a few more cases of labial-

velars in the Pacific, namely in the eastern end of New Guinea, including one

language possessing a particularly elaborate system of such consonants.

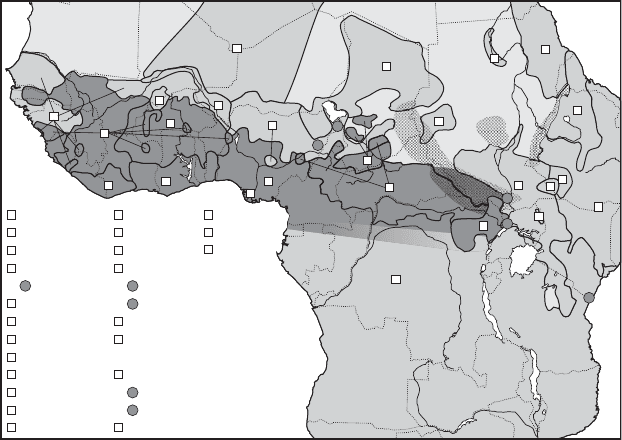

Of great importance for this chapter is the distribution of labial-velars within

Africa, because it resembles that of logophoricity. All African languages in

Maddieson’s sample with such conson ants are spoken in or near the logo-

phoricity area and establish a language set with a genealogical profile similar to

that in table 5.1. His languages with labial-velars come from the following

families: Moru-Mangbetu, Bongo-Bagirmi, Adamawa-Ubangi, Benue-Congo,

Kwa, Gur, Atlantic, Mande, Chadic, and Ijoid. Kru and Nilotic can be added to

this list, because they also have languages with these sounds, the former many,

the latter only a few. The survey is summarized in table 5.2.

In some languages, labial-velar consonants occur as a feature which is

untypical for the family; they are found in the geographical periphery of the

area, namely in the extreme south (Bantu), east (Nilotic) and north (Chadic).

Most of Narrow Bantu lacks labial-ve lar consonants, while its closest

relatives within and adjacent to the area frequently have them. According to

Clements and Rialland (this volume chapter 3), most Bantu languages with

labial-velars are spoken north of a line that stretches from northern Gabon in

the west, along the northern sector of the Congo River to half-way between

Lake Albert and Lake Edward.

6

Table 5.2 Labial-velar consonants across African lineages

Family Stock

Language or

group (branch) Area

Bongo-Bagirmi A Central Sudanic

Moru-Mangbetu B Central Sudanic

Adamawa-Ubangi C N. Niger-Congo

Benue-Congo D N. Niger-Congo except most of

Narrow Bantu

Kwa E N. Niger-Congo

Gur F N. Niger-Congo

Nilotic Q Eastern Sudanic Kuku (West), South Sudan,

Alur (East) North Uganda

Chadic T Afroasiatic Afade, Bacama Northeast Nigeria,

(Central) North Cameroon

Ijoid U –

Kru V N. Niger-Congo

Mande W –

Atlantic X – except North

The Macro-Sudan belt 157

The feature in Nilotic and Chadic is in all probability an innovation due to

contact with languages belonging to the core area. For Kuku and Alur from

Nilotic, linguistic interference from Moru-Mangbetu is explicitly stated by

Dimmendaal (1995b: 100–1, 103) to be responsible for the sound change. This

is parallel to the peripheral status of Nilotic with respect to logophoricity. Since

labial-velars are unusual in Chadic too, the contact explanation can also be

applied to the few Chadic languages concerned; at least Bacama is still today

the neighbor of Adamawa-Ubangi languages.

5.2.3 ATR vowel harmony

The well-known vowel-harmony type based on advanced tongue root (ATR)

is another property of African languages with a distribution similar to the

previous ones; see Clements and Rialland (this volume, chapter 3) for a

characterization of this feature and more discussion. A survey of this feature,

emerging from a summary of Hall et al. (1974), Blench (1995: 89–91), Dim-

mendaal (2001a: 368–73), and Casali (2003), singles out the following

families: Moru-Mangbetu, Bongo-Bagirmi, Adamawa-Ubangi, Benue-Congo,

Kwa, Gur, Kru, Atlantic, Dogon, Mande, Ijoid, Chadic, Cushitic, Omotic,

Surmic, Nilotic, Nubian, and Kado. Hall et al. (1974) and Casali (2003) also

list languages from Saharan, Maban, Furan, and Koman in the northeast

(classified as Nilo-Saharan) as possibly having this vowel-harmony type, while

2

1

4

3

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

X

A

B

C

D

M

Moru-Mangbetu

Bongo-Bagirmi

Adamawa-Ubangi

Benue-Congo

E

F

G

H

J

K

L

Kwa

Gur

Dogon

Songhai

Berber

Saharan

Nubian

M

Cushitic

N

Ethio-Semitic

V

Kru

Mande

W

X

Atlantic

D

Bantu

Chadic

T

Omotic

O

Nilotic

Q

P Surmic

U

Ijoid

Kado

R

Kuliak

S

Furan

Kuku

Alur

Afade

Bacama

5

Mijikenda Bantu

5

1

2

3

4

Map 5.2 Labiovelar consonants across African lineages

Tom Gu

¨

ldemann158

Blench (1995: 90) explicitly excludes them; all sources lack a more detailed

discussion so that these cases remain open and are not listed in table 5.3.

In some families such as Chadic in the north and Nubian, Cushitic, and

Omotic in the east, the property is exceptional. Hall et al. (1974) and especially

Dimmendaal (2001a: 368–73) state that languages of some of these latter

groups as well as individual subgroups within Narrow Niger-Congo (are likely

to) have acquired the vowel-harmony type through contact with languages

where the feature is well entrenched. Such a contact-induced interference has

been treated more extensively for the Tangale group of Chadic by Kleine-

willingho

¨

fer (1990 ) and Jungraithmayr (1992/3); see also Drolc (2004) for

vowel-harmony phenomena in Ndut (Cangi n, Atlantic) induced by contact

with Wolof, another Atlantic language from the Senega mbian subgroup.

5.2.4 Word order S-(AUX)-O-V-X

At least since Heine (1976) it has become established that Africa hosts, besides

languages with more or less consistent word-orders of the types S-V-O,

S-O-V, and V-S-O, a considerable number of languages which have a kind of

Table 5.3 ATR vowel harmony across African lineages

Family Stock

Language or

group (branch) Area

Bongo-Bagirmi A Central Sudanic

Moru-Mangbetu B Central Sudanic

Adamawa-Ubangi C N. Niger-Congo

Benue-Congo D N. Niger-Congo except most of

Narrow Bantu

Kwa E N. Niger-Congo

Gur F N. Niger-Congo

Nubian L Eastern Sudanic Hill Nubian Nuba Mountains

Cushitic M Afroasiatic Somali (East) Horn of Africa

Omotic O Afroasiatic Hamer (South) Southwest Ethiopia

Surmic P Eastern Sudanic

Nilotic Q Nubian

Kuliak R – Ik, So North Uganda

Kado – Krongo Nuba Mountains

Chadic T Afroasiatic Tangale (West) Northeast Nigeria

Ijoid U –

Kru V N. Niger-Congo

Mande W – except West Co

ˆ

te d’Ivoire, Ghana,

Burkina Faso

Atlantic X – except most of South

The Macro-Sudan belt 159

inconsistent word order (his type B). It is characterized in particular by the

combination of S-V-O in the clause and by GEN-N in the noun phrase. This

‘‘mixed’’ type B is often associated with a second word-order pattern on the clause

level, namely S-AUX-O-V-X (X ¼ participant other than S and O). The possible

alternation between the two orders is exemplified by (2) from Akan (Kwa).

(2) a.

O-f

Em-

ma

`

bo

`

fra

´

no

´

sı

`

ka

´

3SG-lend-PAST child DEF money

‘She lent the child money’

b.

O-de

`

sı

`

ka

´

f

Em-

ma

`

bo

`

fra

´

no

´

3SG-AUX mone y lend-PAST child DEF

‘She lent [the] money to the child’ (Manfredi 1997: 109)

The clause structure S-AUX-O-V-X, in which the object and another non-

subject participant are separated from each other by the main verb, is in fact in

some languages the only option (i.e. there is no S-V-O alternative); this holds

particularly for the Mande family, as shown in example (3) from Koranko.

(3) u

`

sı

´

wo

`

la

´

-bu

`

ı

`

yı

´

r

O

1SG PROSPECTIVE that.one CAUS-fall water in

‘I’m going to throw her into the water’ (Kastenholz 1987: 117)

1

2

4

5

6

7

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

X

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

J

K

L

Chadic

Tangale

T

M

Moru-Mangbetu

Bongo-Bagirmi

Adamawa-Ubangi

Benue-Congo

Kwa

Gur

Dogon

Songhai

Berber

Saharan

Nubian

M

Cushitic

N

Ethio-Semitic

Nilotic

Omotic

O

P

Q

Surmic

Mande

U

V

W

Ijoid

Kru

X

Atlantic

Kado

Krongo

R

S

Kuliak

Furan

D

Bantu

1

2

3

4

5

Hill Nubian

Somali

Hamer

6

7

Ik

So

3

Map 5.3 ATR vowel harmony across African lineages

Tom Gu

¨

ldemann160

It is thus an empirically salient and robust word-order type in Africa, which

contrasts with the fact that it is crosslinguistically very rare (see Gensler 1994,

1997; Gensler & Gu

¨

ldemann 2003). Nevertheless, a continental survey of the

feature turns out to be problematic, because it remains to be determined what

the exact criteria are to view a lang uage-specific structure as an instance of it.

Several properties of S-AUX-O-V-X can be focused on: (a) the syntagmatic

split within the predicate since the object intervenes between auxiliary and

main verb; (b) the syntagmatic split between non-subject participants sepa-

rated from each other by the main verb; and (c) the paradigmatic split within a

language between S-AUX-O-V-X and S-V-O. The rationale for the following

survey is not to view the involvement of an auxiliary as a necessary criterion

and to consider languages which have either S-AUX-O-V-X or S-O-V-X as a

major or the only word-order type.

The data are based on Gensler and Gu

¨

ldemann’s(2003) survey, supple-

mented by information that was mad e available in connection with the

workshop ‘‘Distributed predicative syntax’’ held at WOCAL 4, including

Elders (2003) and Childs (2004). According to this material, S-(AUX)-O-V-X

does not occur throughout the continent, but is restricted to languages of the

following families: Songhay, Mande, Atlantic, Kru, Gur, Kwa, Benue-Congo,

parts of Adamawa-Ubangi, and Moru-Mangbetu; it is also a possible structure

in Ju (¼ Northern Khoisa n) and the southern branch of Cushitic.

Heine and Claudi (2001: 43) claim that S-(AUX)-O-V-X ‘‘is neither a matter

of common origin (¼ genetic relationship) nor of language contact (¼ areal

relationship).’’ Instead, they exclusively entertain a grammaticalization

explanation whose basic precondition is that a language combines S-V-O order

in the clause with GEN-N order in the noun phrase (see the above article and

Claudi 1993 for more details). This would suggest that the co-occurrence of

these two word-order features is the ultimate common denominator of lan-

guages with S-(AUX)-O-V-X. However, this is not the case, inter alia because

there are quite a few Benue-Congo and Adamawa-Ubangi languages with the

pattern, but which have N-GEN. Therefore, the proposed functional explan-

ation is unlikely to be an exhaustive account for the emerge nce and the geo-

graphical distribution of S-(AUX)-O-V-X in Africa (see also Gensler 1997 for

some discussion).

In fact, there is no apriorireason why the marked word order should be a

unitary phenomenon and thus have a single explanation for all its attested cases.

Accordingly, a geographically isolated occurrence, as in Ju of southern Africa

and South Cushitic of eastern Africa, does not rule out that the feature can be

explained to a considerable extent in terms of genealogical and areal factors.

With respect to genealogical patterns, Gensler (1994, 1997) makes a case for

reconstructing S-(A UX)-O-V-X to Proto-Niger-Congo (in Greenberg’s Niger-

Kordofanian sense), besides unmarked S-V-O. This becomes even more

The Macro-Sudan belt 161