Hatano Y., Katsumura Y., Mozumder A. (Eds.) Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter - Recent Advances, Applications, and Interfaces

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

30 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

dΩ in the direction Ω(θ,ϕ), measured from the polar axis taken along the direction of the incident

electron,

can be written as

I =

NI d E

d

n

n

0

0 0

( )

( , )

Ω

σ Ω

Ω

0

(3.1)

The subscript 0n indicates a transition from the ground state 0 to an excited or ionized state n. The

quantity dσ

0n

(E

0

,Ω)/dΩ is called the differential cross section for the excitation 0 → n.

Theoretically, the DCS is expressed in terms of scattering amplitude f

0n

(E

0

, Ω), which is derived

from

the asymptotic behavior of the electron wave function, that is,

d E

d

=

k

k

f E

n n

n

σ Ω

Ω

Ω

0

0

( , )

,

0

0

0

( )

2

(3.2)

where

k

0

and k

n

are magnitudes of the electron momentum before and after collision, respectively.

160°

140°

120°

100°

80°

60°

40°

20°

10

4

10

3

10

2

Electron energy (eV)

10

1

10

–24

DDCS (cm

2

/eV sr molecule)

DDCS (cm

2

/eV sr molecule)

10

–23

10

–22

10

–21

10

–20

10

–19

10

–18

10

–24

10

–23

10

–22

10

–21

10

–20

10

–19

10

–18

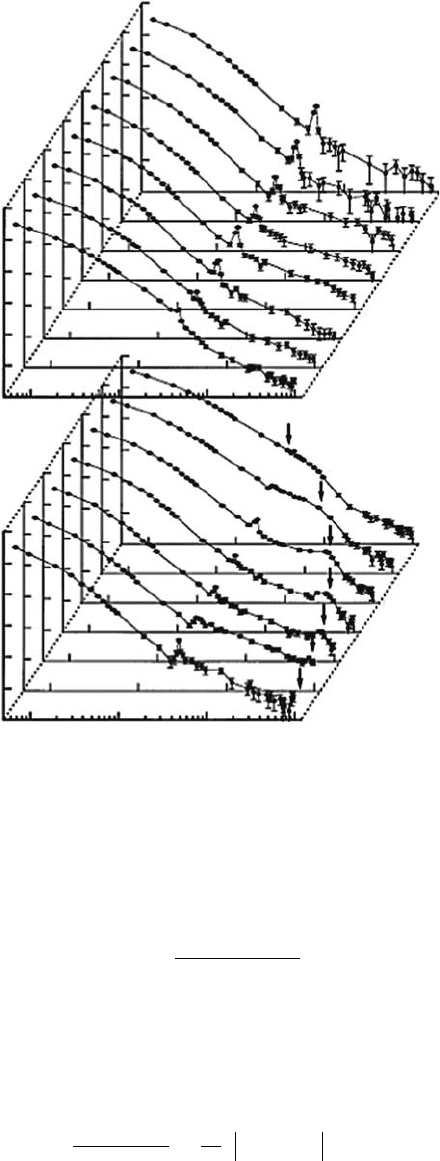

Figure 3.1 DDCS for 6.0MeV/u He

2+

impact on water vapor. The secondary electrons are measured at

7–10,000 eV and 20°–160°. Arrows indicate the binary-encounter peaks. (Reprinted from Ohsawa, D. etal.,

Nucl. Instrum. Methods B,

227, 431, 2005. With permission.)

Electron Collisions with Molecules in the Gas Phase 31

The integral of the DCS over all scattering angles, namely,

q E =

d E

d

d d

n

n

0 0

0

( )

( )

sin

0

σ Ω

Ω

θ θ φ

,

∫∫

(3.3)

is

called the (integral) cross section for the excitation 0 → n.

The

elastic-scattering cross section, q

0

(E

0

), is dened similarly, by replacing the nal state n with

the ground state 0 in Equations 3.1 through 3.3. The effect of elastic scattering on electron transport

phenomena

is normally explained by the momentum-transfer cross section dened by

q E =

d E

d

d d

0 0

0

M

( )

( )

(1 )sin

0

σ Ω

Ω

θ θ θ φ

,

cos−

∫∫

(3.4)

Thesumofthe cross section(3.3) over all possibleexcitation processes(includingthe elastic one), namely,

Q q

n

( ) ( ) ( )E = q E E

0 0 0 0 0

+

∑

(3.5)

is called the total scattering cross section (TCS). From this denition, it is clear that the TCS gives

an

upper bound of the cross section for any individual process.

If

the incident particle has a velocity distribution given by F(v), then the reaction rate constant for

a

process with a cross section q

0n

is calculated as

κ

0

( )

n

v vdv=

∫

q F

n0

(3.6)

0.001

0.01

0.1

1

10

2 4 6 8

10

2 4 6 8

100

2 4 6 8

1000

Energy of secondary electron (eV)

SDCS (10

18

cm

2

eV

–1

)

50 eV

E

0

=100 eV

300 eV

e+H

2

O ionization

200 eV

500 eV

1000 eV

2000 eV

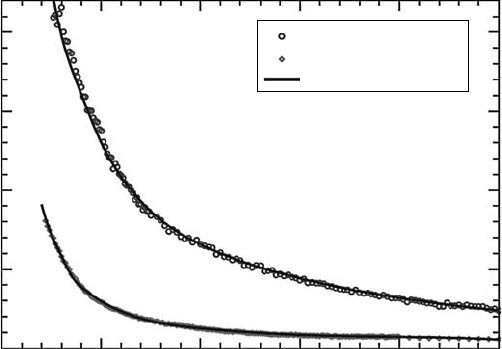

Figure 3.2 SDCS for electron collision with H

2

O measured by Bolorizadeh and Rudd (Bolorizadeh and

Rudd

1986). Incident electron energies (E

0

) are indicated.

32 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

Finally, an average energy loss per unit path length of the incident electron is given as

−

=

∑

dE

dx E

S E i

( )

( ) ( ); N i

(3.7)

S E i dE q E

if if

( ); ( ) ( )=

∑

(3.8)

where

N(i)

is the number density of the target molecule in its ith state

S(E;

i)

is called the stopping cross section

The

summation on the right-hand side of (3.8) is taken over all possible transitions i → f with an

energy loss (dE)

if

. Strictly speaking, elastic scattering also has a contribution to the stopping cross

section.

The contribution is given by

S E

m

M

Eq E

e

M

elas

( ) ( )=

2

0

(3.9)

Here, m

e

and M are masses of the electron and the molecule, respectively, while

q

M

0

is the momen-

tum-transfer cross section dened by Equation 3.4. When the energy of the incident electron is

above the threshold of the rst electronic excited state, the elastic stopping cross section can be

ignored in comparison with inelastic ones. But for subexcitation electrons, the elastic contribution

should

be considered in the evaluation of the energy-loss rate in Equation 3.7.

3.2.3 theory and itS role

Electron collisions with molecules have been studied theoretically for many years. Several elaborate

methods have been developed to calculate collision cross sections (Huo and Gianturco, 1995). This

section does not address the details of these theoretical methods. Instead, general aspects of the

theory

as a tool to complement experimental results are presented in the following text.

One

of the main objectives of theory is to prepare a framework to interpret the results obtained

experimentally (Schneider, 1994). In other words, theory provides the means with which we can

gain insight into the physics underlying collision processes. Furthermore, it is only with theory that

we can predict the results of future experiments. One of the typical examples is the interpretation of

the resonant structure in the energy dependence of the cross section (see Section 3.3). This structure

is thought to be caused by a temporary capture of the incident electron to the molecule. This inter-

pretation is conrmed only through theory. Whenever any structure is found in the experimental

cross section, it tends to be assigned to a resonance. But the assignment should be tested against

theory. Another example is the asymptotic form of the cross section in the limit of high impact

energy. The Born–Bethe theory shows that the cross section for any dipole-allowed transition has

the asymptote (ln E)/E as a function of collision energy, E (Inokuti, 1971). This is a universal law

and often used as a check of the validity of experimental data.

Another important role of collision theory is to supplement the cross-section data obtained

experimentally. In many cases, experimental data do not satisfy the trinity requirement mentioned

in Section 3.1. Normally, relative measurements are much easier than absolute ones. In some cases,

the

experimental cross section on the relative scale is normalized to an absolute value theoretically

obtained at some point of energy. Most of the measurements of the cross section are performed at

a limited number of independent parameters (e.g., incident energies and scattering angles). In this

sense, most experimental data are not comprehensive but fragmentary. Theoretical models have

been

proposed to make these data more comprehensive.

As

is mentioned in Section 3.2.1, a close collision between an electron and a molecule can be approx-

imately described by a binary-encounter theory for collision of the incoming electron and the molecular

Electron Collisions with Molecules in the Gas Phase 33

one. Kim and his colleagues (Kim and Rudd, 1994; Hwang etal., 1996; Kim etal., 1997) derived an

ionization cross section from the classical two-body collision theory. To make the resulting formula

more physically reasonable, they combined this ionization cross section with an asymptotic form of

the quantum mechanical cross section in the high-energy limit (i.e., the Bethe formula). To take into

account the characteristics of the molecule, they incorporated into the resulting formula the binding and

kinetic energies of the molecular electrons. They called this the binary-encounter-dipole (BED) model.

The practical application of this model is shown in Section 3.3.4.1. Kim (2007) also proposed a simple

model to produce cross sections for the excitation of the electronic state. This (called the BEf-scaled

Born cross section) is given in Section 3.3.3.3 in relation to the excitation of H

2

O.

For their Monte Carlo study, Garcia and his group (Muñoz etal., 2007, 2008) obtained elastic cross

sections (particularly DCS) with a theoretical model. First, they prepared a model optical potential for

an electron–atom collision. With this potential, they approximately took into account the effects of

inelastic processes on elastic scattering. Then they adopted the independent atom model (IAM), that

is, the elastic cross section for an electron–molecule collision was obtained by an incoherent sum of

the elastic cross sections for electron scattering from the constituent atoms. In so doing, they approxi-

mately included screening effects to consider the molecular nature of the target. They showed that, at

least for the integral cross section, their model reproduces the experimental data available.

In principle, theory can produce cross sections on an absolute scale. When no experimental data are

available, theoretical cross sections are used for application. However, it is very difcult to evaluate the

accuracy of these cross sections. The reliability of the theory used can be sometimes judged, but it is

generally impossible to numerically estimate the possible error of the cross sections calculated. Great

care should be taken when any theoretical values are adopted in the database for application.

3.3 reCent advanCes in low-energy eleCtron

Collisions

with m

oleCules

3.3.1 overview of the croSS SectionS for electron colliSionS with MoleculeS

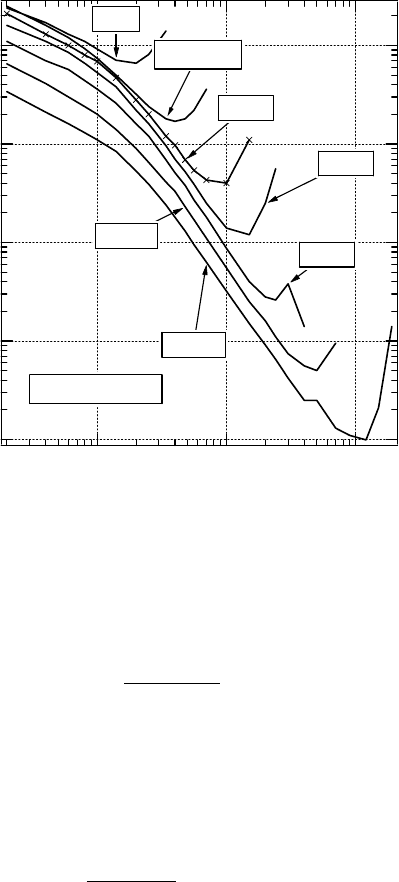

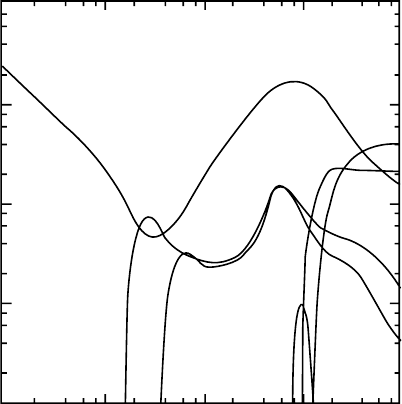

Two typical examples of the cross-section set are presented here: one for H

2

O (Figure 3.3) (Itikawa and

Mason, 2005) and the other for CH

4

(Figure 3.7) (Kurachi and Nakamura, 1990). The electron-impact

energy is covered from 0.1 to 1000eV for H

2

O, and from 0.01 to 100eV for CH

4

. As is described

in Section 3.2.2, collision is classied into two kinds, namely, elastic (0 → 0) and inelastic (0 → n)

processes. An elastic collision, in which internal energy of the molecule is not changed during the

collision, takes place at any energy. Strictly speaking, a small part, ΔE, of the kinetic energy of the

electron is transferred to the target molecule. The relative amount of energy transfer is given by ΔE/E ∼

m

e

/M ∼ 10

−4

, where m

e

is the electron mass and M is the mass of the molecule. In an inelastic collision,

internal energy is changed according to the processes, such as rotational, vibrational, and electronic

excitations; dissociation; ionization; and electron attachment. The relative amounts of energy transfer

to rotational, vibrational, and electronic degrees of freedom are roughly of the order of (m

e

/M)

1/2

:

(m

e

/M)

1/4

: 1. From this, it is clear that the adiabatic approximation holds for rotational and vibrational

motions. In the following text, some details of the cross-section set for H

2

O (Figure 3.3) are given.

Cross sections for CH

4

are discussed in Section 3.3.2.2 in relation to the swarm experiment.

Figure 3.3 shows the recommended values of the cross sections for total scattering, elastic scat-

tering, momentum transfer, rotational transition, vibrational excitations of bending and stretching

modes, and total ionization (Itikawa and Mason, 2005). The gure also shows cross sections for

several different processes of molecular dissociation. They are dissociative attachment to produce

H

−

, dissociative emissions to produce Ly alpha and Balmer alpha lines of H, and A-X emission of

OH, and nally the production of OH in its ground (X) state and O in

1

S state. Each inelastic cross

section

has a threshold and a specic shape of energy dependence.

To

determine a cross section of a certain process over a wide range of energies, several differ-

ent experimental methods described below (i.e., an attenuation method, a swarm technique, and a

34 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

crossed-beam method) must be used in combination. To obtain a reliable (though not necessarily

complete) set of the cross sections, there is no standard way to employ. As one can see in an exten-

sive data compilation, such as is shown in Figure 3.3, it takes efforts of many workers in many

different institutions to produce cross sections for one molecule. In spite of the efforts, some of the

data sets may be fragmentary. Furthermore, results from different laboratories are often discordant.

It is therefore necessary to collect as many sets of data as possible from the literature, to assess their

reliability and to determine the most trustworthy set of data for use in applications. Efforts toward

such data compilations and analysis are being made by various groups, as described in Section 3.4.

As for H

2

O, the cross-section set recommended by Itikawa and Mason (Figure 3.3) does not nec-

essarily satisfy every user. The most serious problem is the excitation of the electronic state. At the

time of compilation, no reliable experimental data were available for the process so that nothing was

recommended for the excitation of the electronic state, as is seen in Figure 3.3. However, the situa-

tion is now improved (see Section 3.3.3.3). Total and elastic-scattering cross sections and the ioniza-

tion process have been well studied. No experimental data are available for rotational excitation,

and values plotted in Figure 3.3 are the result of a theoretical calculation. Some of the other cross

sections are now being revised, which are discussed in the relevant sections below. Particularly for

dissociation

processes, a recent review by McConkey etal. (2008) is very informative and useful.

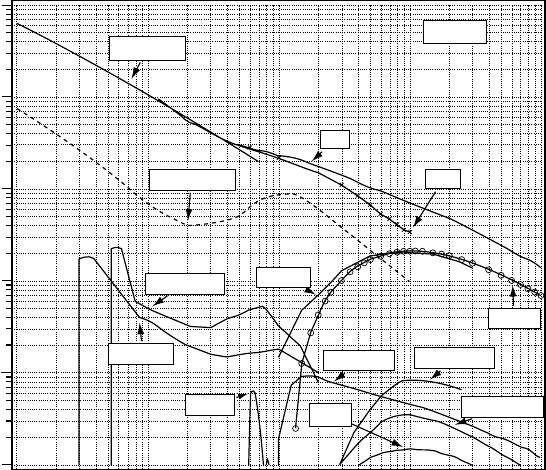

Once

the cross-section data set is determined, useful physical quantities like Equations 3.6 and 3.8

are evaluated. For instance, the stopping cross sections thus calculated are shown for H

2

O in Figure 3.4

(Itikawa, 2007). In thisgure, the stoppingcrosssections are presented only overthe energy region below

10eV. In this region, rotational transition is the most dominant process for stopping the electron. The two

curves for vibrational excitation correspond to the bending (vib2) and stretching (vib13) modes, respec-

tively. The stopping cross section for the excitation of the electronic state (designated as exc.) is based on

a theoretical cross section so that its quantitative accuracy is uncertain. For electron energies above 10eV,

ionization and electronic excitation dominate. We need more detailed information about these processes

(particularly about the excitation of electronic states) to evaluate the stopping cross section.

10

–13

10

–14

10

–15

10

–16

10

–17

10

–18

0.1 1 10

attach

OH A-X

H Lyman α

H Balmer α

ion tot

O(

1

S)

vib bend

vib stretch

tot

mom transf

rot J = 0–1

elas

e+H

2

O

OH(X)

Electron energy (eV)

Cross section (cm

2

)

100 1000

Figure 3.3 Summary of the recommended data on electron collision cross sections for H

2

O. (Reprinted

from

Itikawa, Y. and Mason, N.J., J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data, 34, 1, 2005. With permission.)

Electron Collisions with Molecules in the Gas Phase 35

3.3.2 MeaSureMentS by electron-beaM attenuation and tranSport MethodS

3.3.2.1 total scattering Cross section—an upper bound of Cross section

The TCS, Q, dened by Equation 3.5 is obviously an upper bound of any of the individual cross

sections. It is normally determined with a beam attenuation method. With this method, however,

no information is available for each q

0n

(E

0

) component on the right-hand side of Equation 3.5.

Each individual cross section has to be determined by the measurement of the crossed-beam type

described

in Section 3.3.3.

To

determine Q, one may use the Lambert–Beer law, commonly used in photoabsorption mea-

surements. Suppose that one sends an electron beam (having uniform velocity) of intensity I

0

per

unit area into a gas consisting of N molecules (of a single species) per unit volume. If one determines

the number I of these electrons passing through unit area at a distance L in the gas, then one may

write I/I

0

= exp(−NQL). This relation is valid under a condition of single collision during the pas-

sage of the electron in the gas cell. Such a measurement is feasible for electrons of kinetic energies

between

0.1 and 1000

eV

or higher.

The

apparatus for the attenuation experiment appears to be simple in principle, but a great deal of

ingenuity and care is required to achieve a precision of a few percent or better in the results. In this

experiment, the electrons are assumed to be lost from the beam once they collide with molecules.

Some of the electrons, however, move in the forward direction even after collision. The intensity,I,

should not include these forward-scattering electrons. The reliability of the measured value of Q

critically depends on the care taken about this point. Sometimes, a uniform magnetic eld is applied

in parallel to the electron beam so as to limit the spatial divergence of the electron beam. When a

magnetic eld is applied, its inuence on a transmitted beam must be compensated by a calculation.

10

–15

10

–16

10

–17

rot

elas

exc

10

–18

10

–19

10

–20

0.01

2 24 46 68 8 2 4 6 8

0.1 1 10

Electron energy (eV)

Stopping cross section (eV cm

2

)

vib 2

vib 13

H

2

O

stopping cross section

Figure 3.4 Stopping cross sections for electron collisions with H

2

O. Only those for low-energy electrons

are shown. (Reprinted from Itikawa, Y., Molecular Processes in Plasmas: Collisions of Charged Particles

with Molecules,

Springer, Berlin, Germany, 2007. With permission.)

36 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

Care is needed also in the correction for the effective cell length, because some gas leaks from both

the

entrance and the exit orice of the cell.

Assessing

the total scattering cross-section data available in the literature, Itikawa and Mason

determined the recommended values for H

2

O, as shown in Figure 3.3, which is reproduced in

Figure 3.5. Due to the permanent dipole moment of H

2

O, the TCS increases steeply with decreasing

electron energy. For a comparison, the TCS for CH

4

(collected from a data compilation by Karwasz

etal., 2003) is also plotted in Figure 3.5. In the energy region below about 10 eV, the two sets of

cross sections differ very much from each other. The minimum in the Q of CH

4

at around 0.5eV

corresponds

to the Ramsauer–Townsend minimum, discussed in Section 3.3.2.2.

The

beam attenuation method has been recently extended to extremely-low-energy electrons

(Field etal., 2001). By using photoelectrons, instead of electrons from hot laments, electron beams

of ∼10meV of energy are successfully produced with a very high resolution of a few meV. A beam

of monochromatized light of 786.5 Å from a synchrotron radiation source is used to excite Ar to an

autoionizing state, Ar

+

(

2

P

3/2

), and emit electrons of 5 meV to 4.0eV, with a resolution of about 5meV.

However,

the beam intensity is as weak as about

10

−10

A. Great care is necessary to account for the

contact potential of the analyzer material, and to prevent the leakage of the electric eld outside the

electrode region. Until now, only one laboratory has produced the TCSs in this way, and it has been

suggested

to conrm their result with other experiments.

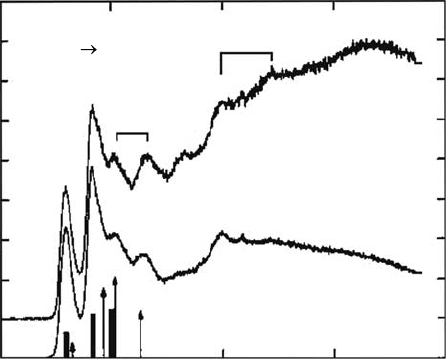

Figure

3.6 shows the TCS measured by Field and his group using their very-low-energy electron

beams (C

ˇ

urík etal., 2006). It should be noted that the electron energy goes down to about 0.02eV,

where the cross section has a value as large as 10

−13

cm

2

. One also should note that the measured

cross section is not the real value of the TCS. Actually, the measured value corresponds to the cross

section excluding a certain part of the forward-scattering electrons. In this sense, the values shown

Total scattering cross section

5

4

3

2

10

–14

10

–15

10

–16

2

3

4

5

6

2

3

4

5

6

6

5

0.1 1 10

Electron energy (eV)

Cross section (cm

2

)

100 1000

H

2

O

CH

4

Figure 3.5 TCSs for electron collisions with H

2

O and CH

4

. The values for H

2

O are the same as those

shown

in Figure 3.3.

Electron Collisions with Molecules in the Gas Phase 37

in Figure 3.6 do not exactly correspond to the ones in Figure 3.5. Further experimentation is needed

for

the TCS of H

2

O at very low energies.

3.3.2.2 the

s

warm

m

ethod

to d

etermine

a Cross-

section

s

et

When electrons are emitted from a source and ow through a gas under an applied uniform elec-

tric eld, they undergo many collisions with gaseous molecules. Macroscopic properties of this

electron swarm can be measured. These properties are the drift velocity, the diffusion coefcient,

and other transport coefcients, as well as the rate constants for excitations, ionization, and elec-

tron attachment. These are functions of the ratio of the electric-eld strength to the gas density,

and determined by the electron energy distribution function (EEDF). Thus, the measured values

of the transport properties can be related to electron–molecule collision cross sections through

the EEDF, which is obtained by solving the Boltzmann equation. The swarm method provides a

set of cross sections, especially at low electron energies (down to 0.01eV), where the electron-

beam method is difcult to apply.

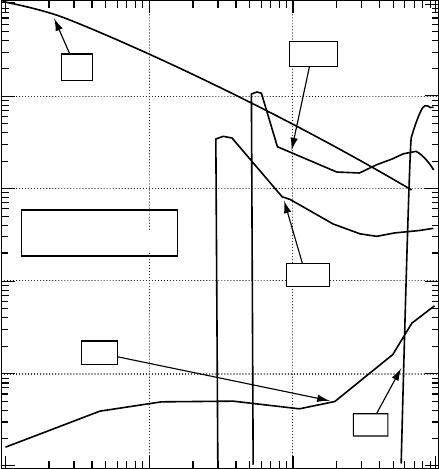

As is easily understood, electron transport involves various kinds of collision processes. It is

difcult to derive cross sections without any ambiguity. Consequently, an analysis of swarm data

usually takes into account some information from other measurements and determines a full set of

cross sections in such a way that the set is consistent with all the available data. Figure 3.7 shows a

set of cross sections thus determined for CH

4

(Kurachi and Nakamura, 1990). Methane is a proto-

type of the single-bond hydrocarbon molecules and is used in many applications, such as radiation

counters. The momentum-transfer cross section,

q

M

0

, dened by Equation 3.4 dominates over all the

electron

energies

shown. In the case of CH

4

,

q

M

0

has a minimum at around 0.34eV. This means that

at the energy around the minimum, electrons pass through the gas almost freely. This minimum

arises from the Ramsauer–Townsend effects, observed also for heavier rare gases (Ar, Kr, and Xe).

To be specic, the phase shift of the s wave (l = 0) of the scattered electron is an integral multiple

of π at this energy, whereas higher partial waves have negligible contributions at such a low energy.

Cross sections for inelastic processes are also obtained, as is shown in Figure 3.7. They are excita-

tions

of vibrational modes, dissociative electron attachment (DEA), dissociation to produce neutral

fragments,

and ionization. Details of vibrational excitation are discussed in Section 3.3.3.3.

2000

1500

1000

Integral cross section

Backward cross section

Fit of the data

500

0

0 50 100

Collision energy (meV)

Cross section (10

–20

m

2

)

150 200 250

Figure 3.6 Results of attenuation experiment with very-low-energy electrons in H

2

O. The upper curve

is the TCS, but with a part of forward scattering excluded (see Section 3.3.2.1). The lower curve is a cross

section for total backward scattering. (Reprinted from C

ˇ

urík, R. etal., Phys. Rev. Lett., 97, 123202-1, 2006.

With permission.)

38 Charged Particle and Photon Interactions with Matter

3.3.3 croSSed-beaM MethodS for the MeaSureMent of croSS Section

3.3.3.1 Crossed-beam methods and the measurement of dCs

In a crossed-beam method, one sends a well-collimated beam of electrons of a xed kinetic

energy, E

0

, into a molecular target (normally in a beam), and analyses the kinetic energy (i.e.,

the so-called residual energy, E

r

) of the scattered electrons. This method provides much more

detailed information than that provided by the attenuation method and certainly reects the

dynamics of the collision process. The electron energy analyzers commonly used are the 127°

electrostatic cylinder and the 180° electrostatic hemisphere (Celotta and Huebner, 1979). These

are also used as monochromators of the energy of the incident electron beams. A hot lament is

commonly used as a source of electrons, with an energy spread of 0.3–0.5 eV. After energy selec-

tion with a monochromator, a resolution of about 30meV and a beam of intensity of about 10

−9

A

(∼17 meV and ∼10

−10

A at best) are usually obtained. In order to maintain the single-collision

condition, the pressure of a gas target must be kept at about 10

−3

torr. This limits the scattering

intensity available. This situation is in sharp contrast with the electron spectroscopy of a solid

surface, which has a much higher atomic density, and hence readily accomplishes an energy

resolution of several meV.

The electron spectrometer can be operated in several different ways. One of the standard ways of

measurement (called the energy-loss mode, EL) is to derive an energy-loss spectrum. In this spectrum,

one plots the intensity of electrons scattered into a xed angle as a function of the energy loss, ΔE

(i.e., ΔE = E

0

− E

r

), for a xed incident electron energy. The location of the energy-loss peak indicates

the excited state of the target molecule, and the height of the peak is proportional to the correspond-

ing cross section for the excitation of the state. Figure 3.8 (Dillon etal., 1989) shows energy-loss

spectra of one of the DNA bases, adenine. Other ways to operate the spectrometer are as follows:

(1) Detecting only the electrons with a specied energy loss with the analyzer, and then sweeping

the incident energy, to observe the energy dependence of a specic excitation process (the excitation

10

–14

10

–15

10

–16

0.01

q

v24

q

m

q

v13

q

v13

q

v24

q

dn

q

i

100q

a

0.1 1 10 100

Electron energy (eV)

Cross section (cm

2

)

10

–17

10

–18

Figure 3.7 A set of electron collision cross sections for CH

4

, determined with a swarm method. (Reprinted

from Kurachi, M. and Nakamura, Y., Electron collision cross sections for SiH

4

, CH

4

, and CF

4

molecules, in

Proceedings of the 13th Symposium on Ion Sources and Ion-Assisted Technology (ISAT’90), Tokyo, Japan,

pp.205–208,

1990. With permission.)

Electron Collisions with Molecules in the Gas Phase 39

function mode, EF, see Figure 3.15). The resulting intensity distribution can reveal the structure due

to resonance. (2) Keeping the residual energy of the scattered electron constant and changing both

the incident energy and the energy loss, to detect the excitation function (the constant residual energy

mode, CRE). With this method, each energy-loss feature is recorded at the same energy above thresh-

old. Thus, it can avoid the effect of different efciencies, if possible, of the detector for different-energy

electrons. (3) Optimizing the spectrometer to detect scattered electrons with near-zero kinetic energy

and sweeping the incident energy (the threshold electron spectroscopy mode, TES [see Figure 3.17]).

Electron scattering from molecules of biological signicance, or biomolecules, is an area that

has been actively studied in line with the recent trends in science and technology. Crossed-beam

methods have been employed for these studies, because these biomolecules are now available com-

mercially and have sublimation characteristics that make a molecular beam easily producible. These

molecules are, however, often in a condition different from the circumstances of real biomolecules.

For example, the target molecules in the experiment are not hydrated and are at a high temperature.

Therefore, there have been serious discussions among atomic physicists, radiation scientists, and

biologists as to how such elementary collision processes can be effective in understanding the radia-

tion effect. As frequently repeated in this book, it is obvious that the OH radical dissociated from

H

2

O is an essential reactant for the radiation damages. But, in this chapter, an electron scattering

from biomolecules is descried as an example of the general study of electron–molecule collisions,

although

it may contribute little to the actual radiation damage.

Typical

examples of the DCS measurement are presented in Figures 3.8 (Dillon etal., 1989) and

3.9 (Vizcaino etal., 2008). The rst measurement of an electron collision with a gas-phase DNA-

base molecule was performed for adenine by Dillon etal. (1989). The electron energy-loss spectrum

was recorded over a range of excitation energy of 3–22eV for scattering angles of 3° and 6°. In

addition to observing accurate positions of the energy-loss peaks, the data solved the long-held con-

tention that the group of peaks in the 6–10eV range belong to transitions originating from valence

πorbitals. In the vapor-phase spectrum, a Rydberg transition corresponding to an n → 3s excitation

is readily observed with a term value of 3.45eV relative to the rst lone-pair ionization potential.

Since early 1990, the bond-breaking process in the molecular constituents of DNA has been

extensively studied by the dissociative attachment method, as described in Section 3.3.4.3.

2 7 12

θ=3°

θ=6°

σ σ

*

π π

*

?

π π

*

π π

*

n 3s

W (eV)

I (rel)

17 22

Figure 3.8 Electron energy-loss spectra for adenine. The incident electron energy is 200eV. Data for two

scattering angles (3° and 6°) are shown. See Dillon etal. (1989) for details. (Reprinted from Dillon, M.A. etal.,

Radiat. Res.,

117, 1, 1989. With permission.)