Harman Oren Solomon. The Price of Altruism: George Price and the Search for the Origins of Kindness

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

preserved its nineteenth-century Hollerith punched-card six-space

markings—“those once-useful claws that are now diminished to useless toe

nails,”—Hamilton would queue along the old kitchen staff’s route to the

basement, roll of five-punched tape ready in hand, watch as the technician set the

toggles to guide the “magic monster” Mercury computer, walk across to collect

the spaghetti-like tape spewing chatteringly out the far side, and rush to an

adjacent room to view the results via a teletype. It was a far cry from sitting in

front of a laptop.

52

But despite the hassle and beneath the natural complications, the teletypes

disclosed a pristine river of logic. Whether you were an ant in a weevil egg, a

wasp in a wild fig, or a mite inside your own mother, there always existed an

optimal solution to the problem of the precise proportion of female to male eggs

to lay. Hamilton called it the “unbeatable strategy,” and discovered to his great

astonishment that, with no Mercury and toggles and teletype and FORTRAN, the

little critters always found it on their own.

It was mind-blowing. Mites “calculating” fractions as precise as 3/14ths?

Hamilton was godless, but this was as close to faith as anything. Now, he knew,

he’d discovered a powerful tool that would help to fathom nature’s wonders. Back

when he was a student at Cambridge he had idly read von Neumann’s great book,

never imagining that it might have anything to do with biology. But there was no

mistaking that here was an evolutionary analog to the prisoner’s dilemma: Fitness

was a “payoff,” the opposing sex-determining genes the “players.” In parasitic

wasps and sex ratios he was dealing in the theory of games.

53

No one seemed to notice at the time that extraordinary sex ratios provided the

very test that Williams had sought to apply to group selection.

54

Hamilton himself

contributed to the confusion: Extraordinary sex ratios couldn’t be an adaptation

for the good of the population, he wrote, since even a tiny bit of outbreeding

would destroy any “altruistic” genes.

55

No, once again this was a family affair;

small spaces like pupae, after all, were like isolated cottages. In line with the

times, parasitic wasps were interpreted as just another nail in the coffin of the

“greater good”: It was gene frequencies that were being maximized, after all, and

they could only do it by manipulating the behavior of related individuals.

Laying down his pencil, Hamilton might have smiled. First rB > C and now sex

ratios: The mathematics of the “gene’s-eye-view” was turning biology into a

“hard” predictive science. Fisher had been right: Selection was a mechanism for

generating an exceedingly high degree of improbability; even altruistic behavior

was fashioned by its unsentimental, ruthless cull. He ended his equation-filled

article, in the grand natural-history tradition of humble cooperation, by thanking a

Dr. Bevan “for information about bark beetles” and a Dr. Lewis “for information

about thrips.”

Group or Individual, Optimization or Chance: Where had true goodness come

from? Wright and Haldane and Fisher had begun the work, uniting Darwin and

Mendel, selection and genes, in a bold evolutionary synthesis. They had argued

among themselves over the relative role of mutation, drift and selection, but their

project had been one of foundation. Now, on the back of Wynne-Edwards and the

“greater good,” younger men like John Maynard Smith, George Williams, and

Bill Hamilton were penetrating further into Nature’s puzzles. Theirs had been a

thought experiment as audacious as Einstein’s, only from the point of view of the

gene rather than a man traveling on a beam of light. Finally, they thought, they

were solving the mysteries of behavior.

In the Amazonian jungle in 1964, Hamilton received a letter from a girlfriend in

London. She was breaking up with him. That week in the forest he had met two

Brazilian kids, Romilda and Godofredo. Alone and morose, he was having serious

doubts whether he’d ever marry or have children of his own. Turning to their

parents, he offered to educate and take care of them as a foster parent back in

England.

Now, four years later, his glum misgivings had proved premature. He was married

to a wonderful woman, Christine, and thinking of starting a family. But a promise

was a promise. The year after publishing “Extraordinary Sex Ratios” in Science

he and Christine were back again in the forest and would be taking Romilda and

Godofredo to Berkshire. Evolution hadn’t selected him to behave this way toward

nonkin, he was now more than ever certain. But lying in his hammock listening to

the beat of the wings of an iridescent dragonfly and a seriema pealing its dawn call

like cracked bells from the hills, he knew it was in his lonely heart, still.

56

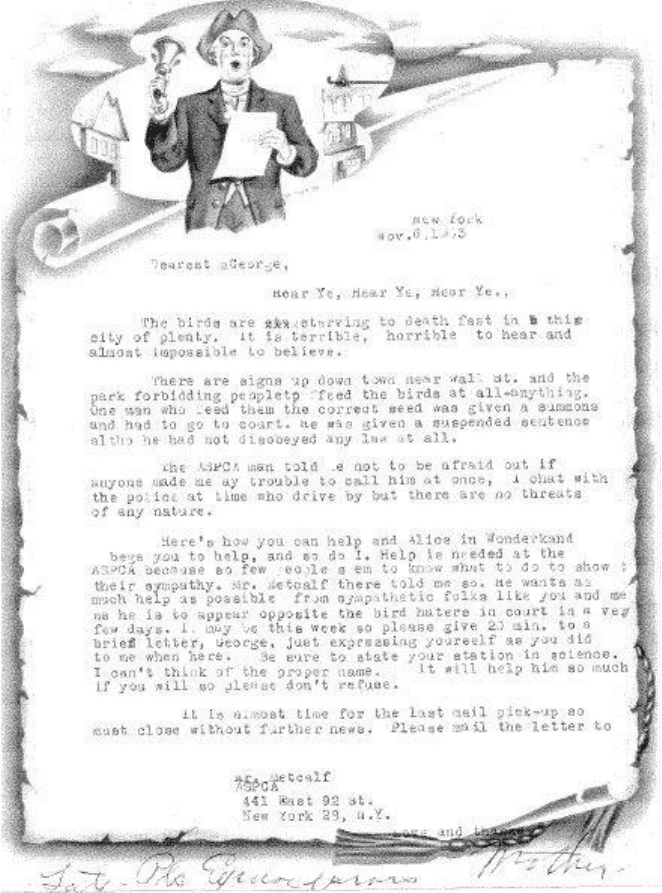

A letter from Alice Price to her son George, November 6, 1963

No Easy Way

In the spring of 1957 Senator Hubert Humphrey had introduced a bill offering

income tax credit for tuition paid to institutions of higher learning. George wrote a

letter of thanks. It was all about education, he thought, and the bill was a step in

the right direction. Still, really, intervention was needed much earlier. Why not

exempt the first six thousand dollars received for teaching in grade school? After

all, the greatest weapon against the Soviets was undoubtedly the first-grade

teacher. “I belong to the ‘as the twig is bent, the tree grows’ school,” George

explained.

1

He had struck up a correspondence with his old senator from Minnesota, and there

were further suggestions to help win the Cold War: Why not send every Russian

two pairs of shoes if their government would free Hungary? Or ten million dollars

worth of polio vaccine if the Hungarian police would stop torturing prisoners? Or

what about radio messages broadcast in Russian extolling the advantages of butter

over guns? And could the senator please send a copy of his “U.S. Foreign Policy

and Disarmament” speech to Congress in April? And the hearings of the Johnson

Preparedness Subcommittee? And had he seen the piece by Donald Harrington

yesterday in the Times? “Of course! Why didn’t I think of that myself?”: an

international court of law to help restrain the Chinese in Formosa. Could the

senator perhaps “plant the idea tactfully within Mr. Dulles’s mind?” George

would very much appreciate it.

2

The senator replied politely that he would welcome his advice and counsel.

George’s views were “eminently sane,” the idea about creating a strong UN

police force just along the lines he had imagined. Price’s overanxious manner

might have struck the senator as somewhat odd, but his replies made George

exceedingly proud. Nothing felt better than a man of stature recognizing his

potential.

Increasingly, writing popular science articles became the perfect vehicle for

gaining notoriety. It was the journalist’s prerogative, after all, to get in touch with

famous people. And so, between “The Physics of Bowling,” “U.S. Begins Search

for Beings in Other Worlds,” and “What We’re Learning from Animals” (all for

Popular Science Monthly), he drove to his old hero Claude Shannon’s home to

write a profile on him for IBM’s magazine, THINK—the two “paddling around”

his lake in “glorious” silence. Between “Achievements of American Science,”

“The Real Threat from Red China” (government brainwashing), and “How to

Hatch an Egghead” (motivate him), he contacted the Nobel laureate Hermann J.

Muller, to ask his views about evolution on other planets. On each occasion the

excuse developed into a conversation, with George trying his very best to impress.

Muller, who was considered by many to be the greatest living geneticist,

remembered “Science and the Supernatural” and complimented him on it; George

replied with quotes from Poe and Keats, and his thoughts about people reading

too much science fiction. Muller thanked him kindly, and the correspondence

ended at that. It was a pattern: the brushup, the exchange, the titillation.

3

If IBM had been stupid enough not to hire him, George was not about to give up

and roll over. On the strength of the piece in Life he had been offered a contract by

Harper & Brothers, and was hard at work on a book now that he hoped would help

to save the world.

It was right about then that Skinner came along.

Adored as a messiah and abhorred as a menace, Harvard professor Burrhus

Frederic Skinner was the most influential psychologist in America. He had an

elongated face and an unsettling smile. The leader of the “behaviorists,” who

likened man to machine, he was reviled by Freudians and humanists. Some called

him “totalitarian,” others “Orwellian” others thought his ideas man’s only hope.

4

George was intrigued. Early Christian thinkers thought it was the “soul” that set

man apart from animal: God-given, immaterial, impalpable, otherworldly. But

what if man were just an animal, firmly planted in the natural world? And what if

men and animals were not all that different from machines?

Such thoughts had been afoot since the Diderots and La Metries of the eighteenth

century, and even earlier, with Hobbes. Now, after Darwin and the rise of

psychology and genetics, Skinner was arguing that freedom and free will were no

more than comfortable illusions. For him autonomy was a “feel-good” invention,

morality a sinister sham. The belief in an “inner man” was like the belief in God, a

superstition, nothing but a symptom of humanity’s failure to understand a

complex world. Whether he liked it or not, man was already controlled by

external influences, some haphazard, others evil, others merely in step with

“convention.” Where things went bad was when man made a fetish of individual

freedom, seeking to give life to the internal “soul” at the expense of orderly

society. In reality, Skinner preached, it was environments and not people, actions

and not feelings, that needed to be changed. The “behavioral technology” called

“operant conditioning” was civilization’s hope for deliverance. Where moral

arguments had failed, it could create a world where man would refrain from

polluting, from overpopulating, from rioting, from hating, even from waging war.

George was a “as the twig bends” man. Visiting Skinner’s Harvard lab on the

pretext of writing a story, he soon befriended “Fred.”

5

The lab was a scene out of wild science fiction. Pigeons playing Ping-Pong, rats

balancing balls on their noses; there was even the pigeon-guided missile, the

“Pelican.” But these were animals. What about humans: Could they be similarly

programmed? And was it punishment or reward that would be more effective in

controlling behavior?

Skinner was convinced that it was reward, and had designed the “Teaching

Machine” to prove it. A question was posed on a screen: If the child answered

correctly he’d be immediately rewarded, not with a grain of corn but with a

printed statement of approval—just as satisfying and effective. Walking George

through the lab, Skinner claimed that kids could be taught arithmetic just as rats

were taught circus acts and pigeons Ping-Pong.

6

George was captivated. “Very quietly,” he wrote for THINK later that month,

“almost unnoticed amid the fanfare over thermonuclear weapons, earth satellites

and moon probes, an important new invention has made its appearance.” To

Skinner he offered: “No doubt the most immediate application for such machines

would be to teach reading and writing to the illiterate masses of Asia and Africa.”

For the last hour he had been sketching out a way to make “a very cheap machine

using an acoustic phonograph with spring motor, plus a paper disc, with controls

to automatically position the phonograph pick-up at the beginning of the question,

stop the phonograph at the end of questions, do the same for the answers, repeat

questions and answers when desired, and skip questions previously answered

correctly.” It could be mass-produced at just five dollars a pop.

7

However useful Skinner’s machines, they got George wondering about larger

questions. Was man in control of his destiny? Was freedom really just a fantasy,

or worse—a trick? Skinner argued that man believes in free will only so that he

can take credit for his “good” behavior. But George had been free to leave his

family, and was taking no credit for good behavior. Clearly there were traits

buried deep in his nature, things that had not necessarily been learned. The

problem was how to manage them, especially self-centeredness and egoism, the

most entrenched natural trait of all.

He translated personal deficiencies into public affairs, the easier, perhaps, to flee

them. Writing drafts of his book for Harper, George remembered Thucydides’

famous description of Athens falling to Sparta on account of selfishness. De

Tocqueville too, he recalled, had lamented how through vain self-absorption and

greed men “lose sight of the close connection that exists between the private

fortune of each of them and the prosperity of all.”

8

He might be a bad family man,

George thought, but he cared about his nation. True self-interest lay in

strengthening the community, in devotion to the country, in paying a personal

price for the good of all. Russia had done it. China had done it. Could America do

it too? Could limits be put in a democracy on the individual pursuit of happiness?

Skinner was hopeful, and George tended to agree. Americans just needed to be

taught that personal sacrifice meant communal reward.

Meanwhile, Harper had reneged on its contract, finding some of his suggestions

“brilliant” and “unexpected,” but the overall book unsalable. With a change of

title, and the help of a talented literary agent, George secured a new publisher and

advance. It was April 1958, and Doubleday would want No Easy Way no later

than July.

9

He was living now in the West Village in New York City. The small loft at 88

Bedford Street was just down the way from the historic town home of Edna St.

Vincent Millay, whose poetry Thomas Hardy called America’s second attraction,

after skyscrapers. Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs were

regulars in the coffeehouses. Dylan Thomas had collapsed and died a few years

earlier drinking at the White Horse Tavern, just a few blocks away, and in a few

years a young Bob Dylan would show up, playing “neo-ethnic” songs in the

coffeehouses in the style of Woody Guthrie. There were writers and poets and

artists and “beats,” and, dapper in his bow tie and crew cut, George was an

anomaly. But he liked the idea that he was an “ex-chemist.” In a strange way,

bohemia appealed to him. There was a kind of prurient satisfaction in being a

straight arrow in a world of chaos. Proudly he had “writer” stamped in his

passport.

10

Still, he could not escape his past. Julia was after him for alimony, and his money

was disappearing fast. He had taken another technical-editing job with IBM, this

time in Poughkeepsie, and was only getting home on weekends. The Doubleday

deadline was killing him. Besides, the world was changing faster than he could

write about it: He had started off calling for armament, but now Russia’s position

on disarmament seemed much more honorable. Should America compete?

Should it withdraw? Could the Russians be trusted? He was confused. He hardly

had time to eat. The world around him was spinning.

11

Loosening his bow tie he popped them in, one by one: iproniazid, Dexedrine,

ephedrine, Seconal; uppers, barbiturates, psychostimulants. Everyone else around

him seemed to be taking them, so what the hell? The effects, he soon learned,

were less than exhilarating. “I’ve spent most of the day so far lying down,” he

wrote to his psychiatrist, Dr. Nathan Kline. The drugs had taken away his panic

but had left him tranquil and sedate. He wasn’t getting anything done. He was

loafing. He felt neither pain nor joy. Worryingly, he was taking “some measures”

to try to release adrenaline from his adrenals; he just couldn’t quite remember

whether it gets through the blood-brain barrier. Did Kline?

12

Then, as the winter of 1960 rolled in, a tumor was discovered in his throat. At first

his internist thought, Hodgkins. But an old Manhattan Project friend who was

chief of X-ray at Memorial Sloan-Kettering sent him to a cancer expert who

diagnosed a nonmalignant thyroid tumor. Recovering from the operation in

March, George was handed a new type of medicine: He had a thyroid imbalance,

and would need to take tablets from now on if he wanted to stay alive and

healthy.

13

There was an instruction manual for a GE electricity and magnetism kit to finish,

and another one on gyros and accelerometers for Sperry-Marine. There was a new

love interest, Joan, a teacher at Bennington College for Women in Vermont.

There was Alice, still with her Japanese roomers, but growing old and infirm.

There was his estranged lighting-expert-inventor brother, Edison, who had taken

over Display, renaming it Edison Price Lighting Company Incorporated and

operating out of 409 East Sixtieth Street. There was Julia, seeking contested

alimony in domestic relations court. There were his daughters, whom he hadn’t

seen for quite some time. There were desperate letters to friends asking for loans.

There was his health. There were the drugs. And then, on April 10, 1960, there

was a letter from Fred Schneider of the Advanced Systems Development Division

at IBM. Regarding his old article in Fortune, IBM was beginning to invest in

computer-aided design (CAD). Would George be interested in joining the

project?

14

That fall a surgeon friend from his days in Minnesota wrote a kind note to say that

his wife had a bad thyroid, too. Don Ferguson was now at the University of

Chicago, and really, George, the thyroid was no big deal. He’d be fine. Still,

didn’t he think that he was wasting himself on those damn manuals? After all, he

had the kind of mind that needed to be applied to real scientific problems.

15

In fact George had been working on two scientific papers, with the hope of once

again gaining a university position. The first was about the fallacies of random

neural networks as they pertained to the organization of the brain, the second a

theory of the function of the hymen.

16

Of course he had absolutely no training in

either of these matters. But he had gone through the literature thoroughly and was

planning to send the papers to Science all the same. He needed one big

breakthrough—one truth, he thought, just one. IBM had toyed with him before,

and by now he had lost interest in his Design Machine. Still, until the papers were

accepted and made him a name, he’d need to take a job to settle his finances.

There could have been worse job opportunities. “The IBM company,” the Annual

Report of 1961 declared,

is engaged in the creation of machines and methods to help find solutions to the

increasingly complex problems occurring in business, government, science,

defense, education, space exploration and nearly every other area of human

endeavor.

17

Gross revenue from domestic operations alone amounted to $1,694,295,547, an

increase of more than $250 million from the previous year. His “unfortunate No

Easy Way,” George wrote to his editor, Dick Winslow, at Doubleday, would need

to be put aside for now. Almost four years after that fateful interview with Piore,

George was joining IBM.

18

A few months after he had become an “official IBMer,” Science wrote back

rejecting his papers. The hymen theory was way too speculative, and a damning

report had slammed “Fallacies” to the ground. “This crotchety, verbose diatribe

has no place in a scientific journal,” an anonymous reviewer had written. George

was “merely a biased reader of other people’s papers.”

19

The last thing he needed was another blow. His shoulder had been dislocated on a

recent climb (his friends called him “kinetic”) and again a few months later,

swimming in rough surf. It was the old injury, compounded by the polio, and it

would need to be taken care of. Recovering at home from the operation in the fall

of 1962, he was gloomy. The Science report was a humiliating rebuke, a slap in

the face from the professional to the impudent amateur. He hadn’t seen his girls in

more than five years. Joan was out of the picture. A Tatiana whom he had met in

the public library was in and then out again. He was almost forty. He had yet to

make his mark. He was starting to wonder about the merits of free will.

As always the only fixture in his life, Alice, came to his side. “You will succeed in

a big way before you know it,” she wrote to him, trying to be encouraging. She

had her own troubles. There was a Mr. Aramachi, thank God, renting the

southeast room, and a Mr. Ishida in the southwest. But then there were the “bird

haters” from the municipality who plastered signs across the park forbidding

feeding them. “The birds are starving to death fast in this city of plenty,” she

wrote to George, despondent. A diminutive octogenarian, she was already well

known to the authorities. Municipal fines and court subpoenas had failed to stop

her. Intransigent, at war with all the cruelty and lack of mercy in the world, Alice

was sneaking pigeons to her home to mend and feed them before releasing them

in Central Park.

20

Back at IBM George had worked a bit on CAD but quickly lost interest entirely. It

was hard for him to get excited about a brainchild he felt had now been stolen

from him in broad daylight. The New Product Line, on the other hand, was doing

a market survey concerning programmed instruction, and George figured he

could help with that. After all, it had to do with Skinner.

They had been friends, but George’s sympathy had soured; in a “market

requirements memorandum” he came down hard on his former pal. Falsely

analogizing from pigeons and dogs to humans, Skinner had presented a simplified

and therefore skewed theory of learning.

21

To him learning was a simple

stimulus-response (S-R) pattern, and any intervening steps should be analyzed

into the basic S-R components. But what if learning in humans really looked more

like this: S-A-B-C-D-E-F-R, and what if A-B-C-D-E-F could not be collapsed

into either stimulus or response? George was certain that this was the case:

Perception (A), attention (B), understanding (C), belief or acceptance (D),

memorization (E), recall (F), and performance (G) were distinguishable

components of learning, and reinforcement worked differently on each of them.

Skinner’s notion that reinforcement led to learning was simple-minded and

misleading. If teaching machines for programmed employee instruction were to

work, one would need a better understanding of how reinforcement affects each

of the components of learning. One would need to know what was innate in man,

and what could be acquired. There were many layers lurking beneath the mystery

of behavior. Free will was more complicated than Skinner thought.

22

In fact George already had ideas on the matter. So much so, he wrote to Winslow

at Doubleday, that he was thinking of writing a book. With No Easy Way not yet

dead and buried, he had risen again like a phoenix from the sand and turned, as

was his pattern, to a new project. “The Reformation of Psychology” seemed too

colorless a title, but he would come up with something better, he was sure. The

main thing was to explain how all the current theories in psychology were

unsupported by masses of current data. Such theories still abounded because a

replacement had not yet been formulated. Reviewing animal and human data

relating to brain function and anatomy, introspection, learning, motivation,

memory, love, and the nature-nurture controversy, George’s book would provide

the missing context. Here he could include the rejected papers on the fallacies of

random neural networks and the function of the hymen, as well as his thoughts

about everything from where memory resides in the brain to how mathematicians

can be useful to psychology. He had left the Village now, he told Winslow, and

was living in (and hating) Poughkeepsie. But the IBM job gave him a good salary

and an enormous amount of freedom, and, given the thumbs-up, he could set to

work on the book right away.

23

The more covetous he grew of his liberty at IBM, the more his coworkers became

suspicious. Who was this George Price: A journalist? A scientist? An inventor? A

quack? And why was he often working from home? Some suspected that he might

be trying to steal IBM secrets for further articles in Life or in Fortune, or maybe

even an “intelligence machine” of his own. Others wondered why he was working

on a book about psychology when he had been contracted to work on the

development of a new computer. Believing in his abilities, his boss, Fred Brooks,

was doing his best to cover for him. It wasn’t easy. Brooks’s own secretary forced

George to buy stationery supplies with his own money. On one of the rare

occasions that he had come in to the office, someone mentioned that there would

soon be a public announcement of the new System/360 computer. “What’s the

360?” George asked. “I never remember these machine numbers, you know.” The

people in the office shot incredulous glances at one another: George was working