Harman Oren Solomon. The Price of Altruism: George Price and the Search for the Origins of Kindness

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

strategies,” to set “impossible goals,” and to reward engineers more handsomely.

But the Design Machine would be the true panacea. A machine to take over the

mathematical and mechanical operations of the drafting department and model

shop, it would revolutionize American industry. How it worked was simple:

An engineer will first describe the shape of a mechanical part, introducing this

information quickly by pressing keys and moving levers. The machine then

translates this into its own internal mathematical language, and within a few

seconds presents to the operator a stereoscopic picture of the part viewed from

any direction specified. Or, within minutes, it will machine the part from metal.

21

It was a system for dealing with models—models constructed out of mathematical

equations stored in the computer memory—and nothing like it yet existed. If

marshaled on a national scale, it could become a repository for all the design and

engineering information able to be programmed. And though intended for

mechanical design, analogs for electronics and for chemistry could easily be

imagined. Finally, here was an idea to make his old teachers at Stuyvesant proud.

Shown the proposal, a leading computer expert was skeptical. In reply George

quickly prepared a seventy-five-page, single-spaced supplementary

memorandum showing how an IBM 704 computer could be incorporated into a

Design Machine, how a complex part could be described to the machine, and how

the machine could display the part—in 3D. The skeptic conceded, and other IBM

experts did, too. Not only could it be done, but it could be done in three to five

years for less than 5 million dollars. The Russians, with their Bison bomber, took

only four years to go through the eight-year development cycle that Americans

needed for the B-52. “The tempo of U.S. technological progress,” George wrote,

“is not an academic matter.” Time was of the essence. No less than the “fate of the

non-communist world” was at stake.

22

George was growing nervous. The “Reds” had just launched Sputnik II, and

marched machines and men in an awesome celebration in Moscow to mark forty

years since the Bolshevik revolution. Russia was gaining on America. In a

strongly worded essay in Life magazine titled “Arguing the Case for Being

Panicky,” he now detailed the precise steps by which the United States would

become a member of the USSR by 1975—if it didn’t wake up and smell the kvass.

Americans were like the people in the Hans Christian Andersen tale “who stood

and watched their emperor parade naked though the streets, and then turned to one

another to praise the beauty of his clothing.” America was like Babylon, Baghdad,

Constantinople, and Rome: the rich, proud, luxuriant nation, smugly confident

and dangerously oblivious to the “tough barbarian adversary, poorly provisioned

and shabbily dressed but high spirited and strong in its drive to conquer.”

23

The article appeared interspersed by a full-page ad from Bell touting the “Seven

Ages of the Telephone.” There was a photo of a smiling mom holding the receiver

to her blond baby’s ear: “Hello, Daddy!” the caption read. Another, of a

“Dynamic Teen” resting on a sofa with plaid skirt and varsity letter, obviated the

footer: “Girls talk to girls. And boy talks to girl. And there are two happy hearts

when she says, ‘I’d love to go!’” And what about “Just Married,” with a brunette

in an office chair with phone and adoring hubby reclining above her?: “Two

starry-eyed young people starting a new life together. The telephone, which is so

much a part of courtship, is also a big help in all the marriage plans.”

What more did Americans want? George asked, indignant: “A Cadillac? A color

television? Lower income taxes?—or to live in freedom?” Would it be luxury or

liberty? The World Series or the Nobel Prize? And who would play the part of a

Franklin or a Hamilton? “Optimism talks” felt good but were confusing. If

America didn’t double its defense budget now, it wouldn’t be long before it

became a Soviet province.

24

He had parachuted from nowhere to the center of a debate about the foundations

of science. He had jumped into the fray over world economics. He had invented a

“Design Machine.” And now he had used a premiere stage to warn of impending

national disaster. With his crew cut, steel-framed round clear-rims, pursed lips,

and bow tie, the unknown thirty-four-year-old from Minnesota cut an original

figure. Whatever you said of him, he was hustling.

Still, there was a weird duality to these disparate interventions: What seemed like

genuine concern for the welfare of America and the world also had the panatela

reek of egotistic smugness. Was he a cocky chemist? A sober economist? A

restless engineer? A prophet? Somehow George Price was simultaneously all of

these—and none.

Whether this was altruism, patriotism, or diarrheic self-promotion, people were

beginning to take notice. “We are proud of you,” Minnesota senator Hubert

Humphrey wrote to him following a full-spread write-up of the Design Machine

in the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune. It was a welcome piece of encouragement:

George was supporting two apartments, two cars, two telephones, and two

attorneys. It was freezing. There were no women to meet, and he was sex starved.

His shoulder still bothered him. Already he considered himself an “ex-chemist,”

yet this was still his job. No, he wrote to Al, it wasn’t due to his usual

“masochism” that he had yet to leave Minnesota; it was due to his reluctance to

work as a chemist, and others’ reluctance to employ him “as a physicist,

economist, writer, or anything else for which I have little training.”

25

Finally he quit, in the winter of 1957, leaving porphyrins, Schwartz, a steady

salary, and his daughters, who had since moved with their mother to Marquette,

all behind. He was moving to Kingston, New York. A respected researcher at one

of America’s premier hospitals, he would now become a rather low-rung

subcontract technical “reviewer,” working for Stevens Engineering Company on

instruction manuals for IBM computers.

George brushed aside accusations of self-destruction. Whether others believed in

his reality meter or not, he was on his way to turning his fortunes around. He

hadn’t yet secured a “big” job, but prospects seemed encouraging. From IBM’s

headquarters at 590 Madison Avenue in New York City, Emanuel Piore had

expressed interest in his Fortune Design Machine. A Jewish immigrant from

Lithuania, Piore had risen to become the navy’s top-ranking scientist, winning its

Distinguished Civilian Service Award and serving on President Eisenhower’s

Science Advisory Committee. As IBM’s director of research, he was leading the

corporation into the era of digital computers. Would George mind coming down

to the offices, he wrote to him, to discuss some of his ideas?

26

The day before the meeting with Piore, on July 15, 1957, an old girlfriend from

the time he was breaking up with Julia appeared rather suddenly in town. Her

name was Anne, she was from the Midwest, and, like Julia, was a Roman

Catholic. He had thought of marrying her before he fell ill with polio, but she had

broken it off for another man. Now, she made it clear, she was once again for the

taking. Still jealous, George said he’d think about it.

The next day he settled into a large camel-colored sofa in a plush office on the

twenty-third floor of the IBM Building. It was still premature for the corporation

to start developing the Design Machine, Piore told him, smiling. But if he was

interested, George and his imaginative ideas would be welcome at Research and

Development. This was quite an offer to a subcontracting technical reviewer, and

from the director of research, no less. But unknown to Piore, George had already

contacted a fancy lawyer from midtown to inquire about a patent. If Piore was not

interested in developing his machine, George wasn’t going to bite. After all, if he

joined IBM he wouldn’t be able to work on a private patent, and millions of

dollars were at stake. They parted with a friendly handshake. George had to run to

make his vacation flight to Puerto Rico—his first trip ever outside America.

27

The following week George went down to the train station to pick up his girls,

who were living now with their mother in Washtenaw County, Michigan. Julia

was a frustrated woman who “never saw the beauty around her.” She considered

her marriage to George “unlucky” after all, she’d been a med-school prospect, and

worked on the Manhattan Project—now she was a third-grade teacher. These

days, when their mother’s dull schoolteacher friends came over for coffee and

cookies, she demanded good manners and hushed voices of her daughters, and,

under no circumstances, any talk of Daddy. When Annamarie and Kathleen

refused to go to church she gave them her untempered piece of mind. There were

rants about Daddy leaving because “they were so awful.” Worst of all, there were

Aunt Edith’s hideous boiled dinners, followed by dreaded stewed prunes. Life

was not exciting.

28

New York was a far cry from Ypsilanti. Quirky and fun and just the opposite of

in-lockstep, George was showing the girls the big world. Carefree and boundless,

they went for hot dogs and ice creams, climbed the Statue of Liberty, visited

Niagara Falls, and listened to Johnnie and Joe’s one-hit wonder, “Over the

Mountain, Across the Sea.” And then there was Yul Brynner starring in The King

and I on Broadway. When George waved good-bye at the end of the week as the

train pulled away from Grand Central, a crying nine-year-old Annamarie and

eight-year-old Kathleen couldn’t have known that it would be one of the last times

they’d spend a week with their father.

He was considering proposing to Anne that week, when he received a notice of

termination from Stevens. IBM was cutting ties to subcontractors, and he would

need to leave his office by Friday. Meanwhile, the Patent, Trade Marks and

Copyrights division at the law offices of William R. Lieberman at 551 Fifth

Avenue wrote to explain that a patent needed to be applied for before November,

when the Fortune piece would turn public domain. Since he didn’t have the

money for this or even a prospect that could promise collateral, it began to sink in

with George that his patent was slipping away. Frantic, he wrote to Piore, asking

to be considered again for the IBM job. But Piore was on a month’s vacation, and

his replacement showed no interest in a fired subcontractor technical editor of

whom he had never heard. George had made up his mind by this time—he wanted

to marry Anne. But he was out of work and in debt, and she was back in the

Midwest and drifting. If only he had proposed to her that day before he met Piore:

Surely he would have been focused on finding a stable job then, and grabbed the

offer handed to him so generously by the director. It was on that fateful day, he

would later claim—July 15, 1957—that his downward spiral began.

29

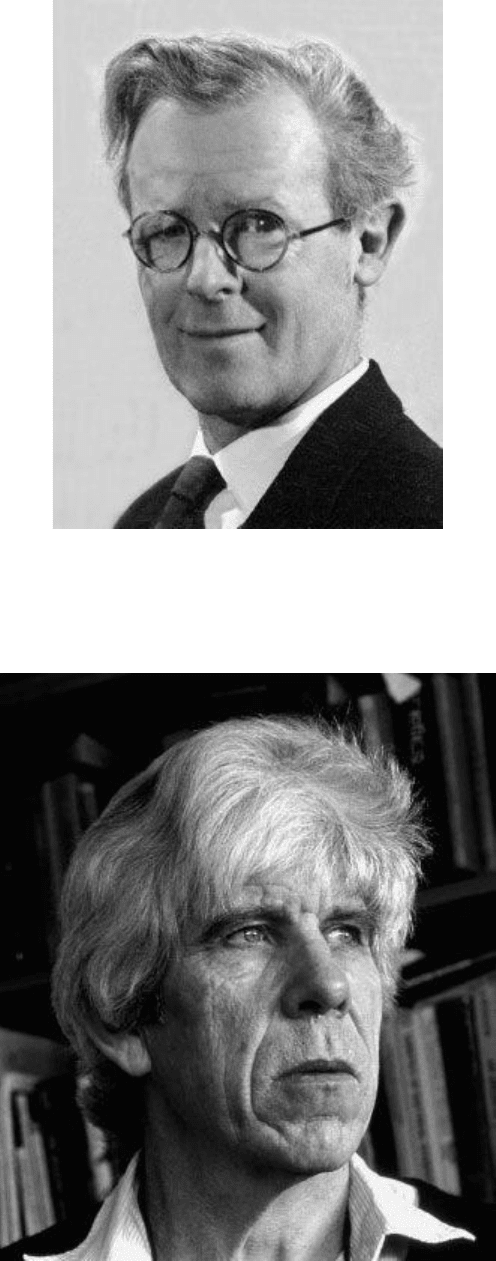

John Maynard Smith (1920–2004)

William D. Hamilton (1936–2000)

Solutions

JBS was in a London hospital bed. Rectal carcinoma, the doctors said. He was

back from India to get the very best treatment available, though the

“auto-obituary” he taped, sitting draped in a sari, wasn’t a very good sign.

Haldane was about to leave this earth, and he knew it. Meanwhile he asked his

student John Maynard Smith to go out to the bookshop to get him something to

read.

1

It wasn’t easy for Maynard Smith to see his mentor in such a state. He was born in

1920 in Wimple Street, London, and childhood had been a lonely affair. He was

eight when his stern and distant ex-military physician father died; an absent

mother provided little comfort beyond the winter home in Berkshire and summer

home in Exmoor, the means for which her wealthy Edinburgh stockbroker family

could afford. Endless hours watching birds in the countryside confirmed both his

love for nature and his isolation.

At Eton, by way of lore, he soon learned that there was one graduate who had

attracted the particular hatred of some of his teachers by betraying his class and

religion. There was a noxious blend of privilege and prejudice at the school, but to

its credit

153

J. B. S. Haldane’s writings were in the library, and seeking them out, John was

captivated. Haldane’s blend of atheism and reason, he thought, “never left you

wallowing in a sense of misty profundity.” Almost naturally, scientific and

political commitments blended: John requested Capital for a school prize he had

won, delved into mathematics, and made peace with the absence of God in his

life. He would be a “puzzle-solver,” he hoped, and a socialist. Shirking his

maternal grandfather’s wish that he join the family’s stockbroker firm, he read

engineering at Trinity College, Cambridge, and joined the Communist Party in

1939.

2

After spending the war years making stress calculations for Miles Aircraft near

Reading, John was ready for a change. Poor eyesight meant he’d never be able to

fly the planes he designed, so he could never really love them either. As for

politics, it was either that or science; one’s heart could be in two places, perhaps,

but the brain was more demanding. Since theoretical physics seemed too difficult

and chemistry a chore, it was to biology and his old love for nature that Maynard

Smith now turned. When he discovered in October 1947 that his hero Haldane

was professor of genetics at UCL, he applied forthwith. “Dear Comrade,” his

letter began,

My interest is mainly in evolution and genetics. My main existing qualification is

that I am a competent mathematician, and in so far as I have shown any ability as

an engineer, it has been in expressing physical problems in terms of mathematics.

I read Huxley’s “Evolution: the New Synthesis,” and there seemed to be plenty of

scope for a mathematical approach to the subject of natural selection, the origin

of species, and so on.

3

Whether he was in a good mood that day or genuinely impressed, JBS fired back a

letter of acceptance. It proved a smart decision: As an aircraft engineer John had

learned to trust models and the necessary simplifications they demanded. After

all, if RAF fighter planes could stay in the sky even though dry calculations on

land assumed incompressible air (refuted by the pneumatic tires and inflated life

jackets), simplifying assumptions could be valuable.

4

Of course, JBS had known

this ever since he set foot in biology.

Maynard Smith made his way to the bookshop. Please don’t die, he thought. Not

yet.

He returned from Dillon’s with a big fat book, Animal Dispersion in Relation to

Social Behaviour, by an author with a long name. The son of the headmaster of

Leeds Grammar School, who retired to become rector of the picturesque country

parish of Kirkland in the Vale of York, Vero Cope Wynne-Edwards had grown up

chasing rabbits in the Pennine hills. At Rugby his buddies called him “Wynne”

and together, he’d remember, they “collected plants and Lepidoptera, found

birds’ nests, hunted for fossils in the local cement pits, ‘fished’ in ponds for

aquatic life, made drawings of ‘scratch dials’ on medieval church walls, and

‘excavated’ for pottery in a Roman camp on Watling Street.”

5

By the time he

arrived as an undergraduate at New College, Oxford, in 1924, his heart was set on

zoology. His teachers were giants: E. S. Goodrich for comparative anatomy,

Gavin de Beer for experimental embryology, E. B. Ford for genetics, Julian

Huxley for general zoology, Charles Elton for ecology. When Huxley left for

King’s College, London, in 1925, it was Elton who loomed large in his education.

Elton was now systematically trapping voles and wood mice in Bagley Wood near

Oxford, trying to figure out their dynamics. Does the size of wild populations of

animals fluctuate in a periodic cycle, he wanted to know, and if so, what was the

cause?

6

Elton saw that size did fluctuate, but he never solved the mystery: Was it due to

weather, the food supply, migration, predator-prey oscillations? No one seemed

to know. It was just around then that he gave Wynne-Edwards a book to read, The

Population Problem. Written in 1922 by a former student of Huxley’s who would

go on to become the director of the London School of Economics and be knighted

for public service, it made a revolutionary claim. Contrary to Malthus, Alexander

Carr-Saunders argued, humans could do without disaster. Neither plagues nor war

nor famine nor any form of “natural corrective” was necessary to provide the

perfect fit between what the world can feed and the number of hungry mouths.

When there was plenty, man procreated generously; when there was dearth, he

procreated less. Neither a slave to the elements nor a victim of the earth, he was

perfectly attuned to his environment. This much evolution had taught us: The

primitive tribes that survived into modernity were exercising population control.

And density was always at its optimum.

7

Forty years later, when Wynne-Edwards was writing the book Maynard Smith

now brought to the dying Haldane, he suddenly understood. He was a professor at

Aberdeen, an Englishman with a Welsh name who had lived half his life in

Scotland. Like Kropotkin, he had made expeditions to northern lands, where the

harsh elements had driven animals to cooperate.

8

If competition existed in nature,

the Arctic taught him, it was directed at the environment, and animals had

developed a myriad of social mechanisms to cope. Already in 1937, on the Baffin

Islands’ coastline, he observed that only between one-third and two-fifths of the

fulmars in the breeding colony mated while the rest were pushed into marginal

territories and often died.

9

What a clever way to prevent overexploitation! Even

more ingenious was the chorus of singing accompanying each breeding season:

Short of using a calculator, it was the best way for the flock to assess its size and,

surveying its resources, reproduce accordingly. Now, in 1962, as he sat down to

explain such phenomena after years of thought, he fathomed his debt to

Carr-Saunders. Birds, just like primitive man, were regulating their numbers.

10

It was an idea, some thought, that flew smack in the face of Darwinism. Man

might exercise birth control, but birds? Surely their brains were no match for the

inexorable natural imperative to procreate, the ultimate arbiter of the survival of

the strong. In the 1930s Julian Huxley had sent another of his students to the

tropics to study Darwin’s old finches. What David Lack saw there was that

competition for food was rampant, but that slight differences between

geographically isolated groups might reduce it.

11

Each group of finches

specializing in a particular food in a particular habitat made for a wonderful

mechanism to get out of the others’ way; gradually, genetically, the populations

became distinct. Nature, in other words, would go to great lengths to avert

conflict, even to the end of divining new species. But as powerful as the force of

competition, more powerful—since more fundamental—was the instinct to

procreate. Individuals were out to maximize their fitness, to sire just as much as

they could. The idea of altruistic birds passing up a number for the greater good

made absolutely no sense.

12

Unless, of course, natural selection was operating on the group, which was

exactly what Wynne-Edwards was arguing. Drawing on Wright’s model of group

selection, Wheeler’s superorganism, Emerson’s homeostasis, and Allee’s fowl

hierarchies, he made a nonmathematical case for the collective. Individuality was

important but subordinate: When the physiology of the singleton came up against

the “viability and survival of the stock or race as a whole,” group selection was

bound to be the victor and individual reproductive restraint the result. It was just

like with fishing: If every fisherman set his net to catch just as many fish as he

could, the village folk would quickly find themselves “entering a spiral of

diminishing returns.” If, however, an agreement was reached over the maximum

catch for each, depletion of the villagers’ maritime food source could be happily

avoided.

13

As with fishermen and their catch, so with fulmars (and red grouse and

many other birds) and their environment: To prevent exhausting limited

resources, numbers could be regulated by social convention for the benefit of

all.

14

Wynne-Edwards was certain that he was walking in the path of a giant. Darwin

had translated Malthus back into nature as he had translated Carr-Saunders.

Darwin had used the analogy of artificial selection to explain natural selection as

he had used fishing to explain population regulation. But Darwin had also written:

Whatever the cause may be of each slight difference in the off spring from their

parents—and a cause for each must exist—it is the steady accumulation, through

natural selection, of such differences, when beneficial to the individual, that gives

rise to all the more modifications of structure, by which the innumerable beings

on the face of this earth are enabled to struggle with each other, and the best

adapted to survive.

15

Now Wynne-Edwards felt, after more than a century, that he’d understood what

even the great master had failed to fathom: Adaptations work for the good of

populations, not of individuals.

On his deathbed JBS just chuckled. “Smith, do you know what this book says?”

he asked his devoted student, with his usual mischievous air:

Well, there are these blackcock, you see, and the males are all strutting around,

and every so often, a female comes along, and one of them mates with her. And

they’ve got this stick, and every time they mate with a female, they cut a little

notch in it. And when they’ve cut twelve notches, if another female comes along,

they say, “Now, ladies, enough is enough!”

16

When it became clear that the best medicine in the world wouldn’t save him,

Haldane returned to India. Clearly he hadn’t been impressed by the biological

argument for the greater good, a fact that did not stop him from dying a devoted

Marxist on December 1, 1964.

Maynard Smith was less of a mule than his teacher. The Lysenko affair, the

purges, and the invasion of Hungary in the fall of 1956 had been enough for him.

Without giving up the sentiment, he gave up the Party, increasingly turning to

model evolution and nature. It wasn’t easy: “Why do theory when Haldane is

sitting in the room next door?”

17

In the beginning he stuck to fly genetics. But

gradually, with Haldane’s move to India in 1957, John’s confidence had grown.

He was ready to take on evolution on his own.

John hadn’t read Wynne-Edwards’s book before he brought it to Haldane, but

now decided to pay attention. Reviews of the tome had been mixed. Lack, of

course, hated it. So did Wynne-Edwards’s beloved teacher Elton who judged it

“messianic” and “rather wooly.”

18

Many, however, found the notion of a “balance

of nature” plausible, and, more importantly, deeply relevant to man.

Wynne-Edwards himself egged them along. That summer he had written an

article for Scientific American that began: “In population growth the human

species is conspicuously out of line with the rest of the animal kingdom.”

19

Man

was virtually alone in showing a long-term upward trend in numbers. It was a

bright red warning sign: However highly he thought of himself, compared to

fulmars and red grouse his social skills were retarded. Modern individual

freedom, alas, had trampled tribal homeostatic wisdom.

Just like Darwin, he was trying to bring animals and man closer together; he had

shown convincingly, an anonymous reviewer in the Times Literary Supplement

wrote, that “social life in man…is no unique affair, but the culmination of a very

widespread biological phenomenon.”

20

The trouble was that they were drifting

apart. This much, at least, was clear to the anxious reviewer in The Nation:

In Wynne-Edwards’ proofs we can see reflected the breakdown of relations

between parents and children, the male’s and female’s diminished attachment,

the constant migration of peoples, the female’s objection to being just a breeder,

the male’s resentment of being just a provider, smaller families, divorces,

desertions, minorities escaping from “ghettos,” elites struggling to keep out the

invaders, the increase of homosexuality and neuroticism, alcohol and drugs, and

above all, the evidence that young people, the group most sensitive to social

stress, desire violence, especially if it is unprofitable and senseless: in all this we

see that human society is reacting just as Wynne-Edwards says a crowded society

should. It is giving a warning which nobody heeds; even when they see the Sunday

cars jamming the highways, as in a dance of gnats, or a swarming of locusts.

21

Maynard Smith took a cool look at the data. Despite the vogue of

population-explosion hysteria there was no need to get excited. Theoretically,

though, if group selection worked, short of decreasing homosexuality and

clearing up traffic jams, it could be an important mechanism in evolution.

He himself had been contemplating the phenomenon of aging. Why, for heaven’s

sake, would evolution select for the degrading of the body: Wouldn’t it be better

to be able to reproduce indefinitely? The nineteenth-century giant August

Weismann had considered the conundrum and thought the answer lay with the

collective: Evolution pushed individuals into old age to make room for the next