Harman Oren Solomon. The Price of Altruism: George Price and the Search for the Origins of Kindness

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Since supply had been short, George was the only Price not to get his gamma

globulin. Away from his family now, he had contracted the disease and was in a

hospital bed, exhausted. Alice begged him to remember how much she loved him.

Hoping to pick up her boy’s spirits, she wrote of a lavish banquet at the Waldorf

thrown by her Japanese boarder Mr. Washio in honor of the imperial prince of

Japan. It gave him little comfort. He was thirty-one years old. His future was

uncertain. Depressed and alone, George Price was helplessly roaming.

58

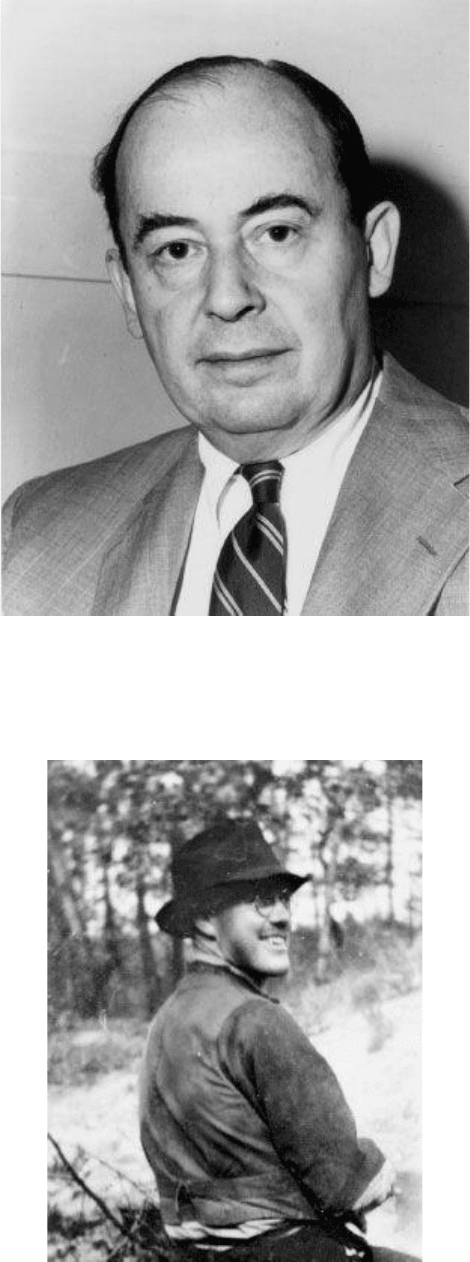

John von Neumann (1903–1957)

Warder Clyde Allee (1885–1955)

Friendly Starfish, Selfish Games

I am violently anti-Communist,” the man intoned in a low accented voice, “and a

good deal more militaristic than most.” It was January 1955, Capitol Hill, and not

a senator in the confirmation hearing room stirred. John von Neumann was going

to be sworn in as a new member of the Atomic Energy Commission, and John von

Neumann was a man to listen to.

1

The H-bomb was on everyone’s mind. Back in 1952 the “Ivy Mike” trial had

destroyed the Enewetok atoll. It was official: The bomb was terrible and viable.

But it would take years to build an arsenal, be massively expensive, and would

have to be accomplished under a veil of complete secrecy. Still, in possession of a

large stockpile, America would unequivocally rule the world. That is, if Russia

didn’t have its own program too. If it did, the arsenals would cancel each other

out, with the already costly expense and effort incurred. Should she “defect,”

then, and build the arsenal, or “cooperate” and hold off? Clearly each side would

prefer that no one stockpile, rather than both stockpiling for no net gain. But each

side might also decide to build its H-bombs either in the hopes of gaining the

upper hand or out of fear of being caught without them.

It was a prisoner’s dilemma, and for von Neumann the solution was clear. The

Soviets could not be trusted. To save itself and the world, America would need to

wage a preventive war, to become, as Secretary of the Navy Francis P. Matthews

had called it earlier in the decade, vicious “aggressors for peace.” But when? Von

Neumann was adamant. With the room hanging on his every word, he said: “If

you say why not bomb them tomorrow, I say why not today? If you say today at 5

o’clock, I say why not one o’clock?”

2

Why was a mathematician being asked by the U.S. Senate whether and when to

use the most destructive weapon in history? Surely he was one of the few people

who had the knowledge to make the crucial calculations that would make or break

the project. But the real reason was different. The H-bomb dilemma hinged on the

mystery of human nature. It had been a quest that traveled through economics and

biology. And John von Neumann, people said, had finally cracked the nut.

The eighteenth century Scottish economist Adam Smith had a simple message to

convey: Under certain conditions free economic competition will lead to the best

allocation of society’s resources. It sounded like a paradox, but it was

unequivocally true: Unfettered contest will by an “invisible hand” maximize

society’s benefits. The more ruthless the competition, the greater the social good;

individual selfishness leads to collective benefit and plenty.

3

By the time Thorstein Veblen arrived as a professor at the University of Chicago

when it opened its gates in 1892, this economic worldview was referred to as

“classical.” Welded now more strongly to the political theory of laissez-faire,

Adam Smith’s legacy beckoned a new name. Veblen called it “neoclassical

economics” and didn’t shy away from expressing his view: He absolutely hated

it.

4

It was said of Veblen—born in Cato, Wisconsin, to Norwegian immigrant

parents—that taking one of his classes was like “undergoing a vivisection without

anesthetic.” A notoriously bad teacher, he was also a formidable critic. The basic

assumption that individuals pursuing their own self-interest necessarily promote

the good of society was to him both insipid and false. Capitalism was leading to

“conspicuous consumption” and “conspicuous leisure.” Not only did this bring

waste and inefficiency, it suppressed fundamental human instincts:

acquisitiveness, workmanship, parenthood, and idle curiosity. Forms of social

control could be used to reawaken them, but this could only be accomplished with

the help of a broad science of human behavior. With its exclusive dependence on

price theory, neoclassical economics was nothing but a narrow “hedonistic

calculus.” Based on “immutable premises,” it had little to do with reality.

5

At Yale political economy was associated with social science, at Johns Hopkins

with political science, and at Columbia with politics. Chicago was the first

university in North America to create an independent department of economics.

Veblen had long been kicked out of the university for impropriety; girls liked him,

it was said, and he didn’t exactly object.

6

Gradually, a worldview almost directly

opposed to his own became dominant.

“All talk of social control is nonsense,” Frank Knight was often heard saying in

his deep, magisterial voice. The oldest of eleven children raised in religious

orthodoxy in McLean County, Illinois, Knight had grown up to become a Chicago

professor of economics and a notorious slayer of sacred cows. Clergy and medics

were quacks, the institutions of social order imposters, the prevailing moral

norms—slaves to fashion. Knight was suspicious of the political system and even

more of politicians. “The probability of the people in power being individuals

who would dislike the possession and exercise of power is on a level with the

probability that an extremely tender-hearted person would get the job of whipping

master in a slave plantation.” In Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit he provided the first

complete formulation of perfect competition—unfettered, unencumbered,

uncontrolled. Perfect competition was important not because it was always most

economically efficient, though it most certainly usually was. Perfect competition

was important because it guaranteed individual freedom, and nothing—not the

injustice of luck nor the trampling of acceptable standards of fairness—was more

important than that.

7

The way Knight saw things, societies have five economic problems: How to

decide which goods and services to produce and how much of them; how to

organize the available productive forces and materials among the various lines of

industry and coordinate their use; how to distribute the goods and services; how to

bring consumption in line with production; and how to ensure continued

economic growth and improvement of the social structure. All five of the

problems involve making choices, and there are two alternative mechanisms for

directing how such choices should be made: at one extreme, central planning

based on the command principle, at the other—a free-market system with

voluntary exchange. More and more people in the Economics Department at

Chicago had fewer and fewer doubts about which was the superior system.

Central planning inevitably became linked with political totalitarianism;

free-market went hand in hand with democracy.

8

“The theory and teaching that there is a God is a lie.”

The words hit Warder Clyde Allee on the head like an iron gavel hurled from a

heavenless sky. He had not been prepared for this. There was silence in the lecture

hall. He was confused, saddened. Most of all he was filled with a surge of pity. He

felt sorry for the misguided man, his animal evolution professor, a controversial

figure who would leave his post some years later on account of an ugly courtroom

divorce. He had often heard of such people—infidels, atheists and that sort—but

this was the first one he had met, and he planned to show him the error of his

ways.

9

It was the fall of 1908, Hull Court, University of Chicago. Allee had arrived that

summer from Indiana, a strapping, broad-faced twenty-three-year-old, his burly

frame and callused hands signs of years of labor on the family farm. Balding and

sporting round spectacles, he looked like an intellectual football player, which, in

fact, he had been as an undergraduate at Earlham College. Warder’s father, John

Wesley Allee, was the son of a Methodist minister from Parke County. When he

fell in love with and married Mary Emily Newlin, whose forefathers had

established the nearby Quaker settlement of Bloomingdale, he became a

“convinced Friend,” but still took the family to the Methodist church from time to

time. At eleven Warder was officially converted at a revival meeting. Earlham

was the pride of the old Quaker settlements south of Lake Michigan, which had

played a role in the Underground Railroad, sneaking black slaves on “Tracks to

Freedom” into Canada in the mid-1800s. When he graduated from high school it

was only natural that Warder enrolled, joining the football team and becoming a

“Hustlin’ Quaker.”

10

Now he was at Chicago, a graduate student in the Zoology Department. The

cloistered walkways, grass quads, and stone Gothic buildings were a far cry from

the open fields and broad woodlands of Indiana where, as a boy, he had fallen in

love with nature. Still, Oekologie had been a term invented by the German

biologist Ernst Haeckel back in 1866 to designate the study of the relations of

organisms to their environments, and Chicago was one of the few places in

America where ecology could be studied. Warder had arrived a traditional

believer. He was excited: Here he would study the nature God had instilled in all

His creatures. Wide-eyed, he did not yet know that science would soon fix all that.

Isopods are ugly little creatures. Leggy and segmented, they look like a

mysterious aquatic blend of scorpion and cricket. Allee was in love. Excited, he

determined he’d crack the mystery of the tiny crustacean, abundant in shallow

waters, the deep sea, and freshwater streams and ponds.

Creating artificial currents in the lab, he observed that stream isopods moved

toward the current more than pond ones, except when their metabolic rate was low

when they were breeding. Since oxygen and carbon dioxide affected metabolic

rate, and differed from streams to ponds, it had to be the gases that explained the

creatures’ behavior.

Using depression agents like low oxygen, chloretone, potassium cyanide, low

temperature and starvation, he could make stream isopods act like pond ones.

Conversely, with high oxygen, caffeine, and elevated temperatures, lazy pond

dwellers morphed into energized stream sprinters. Since all the isopods were from

the same species, differences in behavior could not be due to heredity. Clearly it

was all about interaction with the environment.

The discovery shook his religious foundations. Hadn’t the Deity instilled

behavior in His creations? If so, how could coffee be so powerful? The iron gavel,

he now saw, really did fall from a heavenless sky. There was no “hand of God” to

behold, only physics and chemistry. Science was winning out over the

supernatural.

11

After graduating with a doctorate, Allee was growing uneasy. Married now with a

child, he was increasingly disturbed by the war. Why, for heaven’s sake, this

horrific bloodshed and carnage? At Chicago science might have laid his

childhood belief in an all-powerful God to eternal rest, but at times like this roots

provided comfort. If he couldn’t pacify unbelief, he could sure as hell deify

pacifism. That March he was appointed chairman of the Quaker War Service for

civilian relief in Chicago, an outfit that had grown out of the Monthly Meeting of

Friends.

It was early 1917, and the United States still remained on the sidelines. Already

conscientious objectors were being humiliated and beaten in military training

camps and prisons. Couldn’t enlistment in the newly formed American Friends

Service Committee, aiding relief and reconstruction work abroad, qualify as

conscription, a form of noncombatant service during war? After all, liberal

pacifism held both the individual and the state responsible for the welfare and

rights of the citizen. Conscription to go kill and die in war was in direct violation

of this most holy of commitments. Individualism was the bedrock of democracy

because it meant the assertion of human freedom, not the vulgar triumph of

egoism. The least government could do in times of war was to allow pacifists to

provide their service in nonviolent currencies.

Allee had recently been appointed professor of biology at Lake Forest College.

He had read Kropotkin and in his gut knew that he must be right. But he had yet to

convince himself of the biological justification for peace and cooperation with an

original scientific discovery of his own.

In the college chapel he preached on the rights of conscientious objectors. When

the administration forbade him to preach in the chapel again, he spoke up in the

classroom. The college docked his salary. A few faculty and students were heard

murmuring the word “traitor” under their breath. Traitor? The local Springfield

News-Report wasn’t so inhibited: “Sometimes war is unavoidable, and college

professors are no more necessary to civilization than carpenters and cobblers.”

Allee’s was a “most convenient theory.” If a choice had to be made, “we should

prefer to give up the professors.”

12

In April, Congress voted to enter the Great War. The requests of the American

Friends’ Service had been rejected. At Lake Forest, Allee waited for more

peaceful times. If he wanted to find scientific proof to combat the folly of human

warfare, he would need to go someplace else.

On the afternoon of December 28, 1917, the delegates shuffled into the Animal

Morphology Building at the University of Minnesota blowing into their freezing

hands. The newly established National Research Council could easily envision

how physicists and mathematicians, chemists and geologists, might lend a hand to

the war effort. But what about biologists? At the annual meeting of American

Society of Zoologists, a special session on “The Value and Service of Zoological

Science” had been hurriedly convened. The delegates settled quietly in their

chairs.

13

Darwinism had become about as German as liverwurst. Back in 1859, when he

was under attack in England for The Origin of Species, Darwin wrote to a

colleague: “The support which I receive from Germany is my chief ground for

hoping that our views will ultimately prevail.” And although he himself had

carefully avoided any political implications for man, in Germany, Darwinism was

interpreted as having repercussions for the future of civilization. It was Ludwig

Woltmann, a German, who first gave the enterprise its name. Amounting to a

revolt against Judeo-Christian and neo-Kantian ethics, “social Darwinism”

advanced a set of biologized beliefs: The moral sense is a biological instinct, not a

spiritual endowment; human races are unequal; biology is destiny; the welfare of

the individual is subservient to the health of the group; the struggle for existence

renders war and death necessary to progress; progress and biological purification

are one and the same. It was this distortion of Darwin’s theory, many American

zoologists claimed, that was blowing wind into Germany’s war sails.

14

No one made this clearer than the Stanford entomologist Vernon Kellogg.

Published earlier that year, Headquarters Night was an account of his war

experiences as the chief liaison of the Commission for Relief of Belgium to the

German high command in France. “The creed of the Allmacht of a natural

selection based on violent and fatal competition is the gospel of the German

intellectuals,” Kellogg wrote; “all else is illusion and anathema.” Former

president Theodore Roosevelt agreed. In the preface to the book, he broadcast:

“The man who reads Kellogg’s sketch and yet fails to see why we are at war, and

why we must accept no peace save that of overwhelming victory, is neither a good

American nor a true lover of mankind.” Formerly a pacifist, Kellogg had now

changed his colors. Only a “war to end all wars” could save civilization.

15

The delegates perked their ears in attention. If they could defeat German

Darwinism on the scientific battlefield, they’d be lending their shoulders to the

war effort. One by one, the big guns were paraded to make the cooperatist case:

Did not Herbert Spencer argue that evolution led life from the simple to the

complex, from the homogeneous to the heterogeneous? Had he not explained how

the ensuing specialization of function necessitates cooperation, the better to bring

about an integrated whole? And wasn’t society just like an organism, comprised

of individual parts each contributing to the community? Sure, he had later

abandoned such ideals to paint a picture of a cutthroat struggle for survival, but he

had been more insightful as a young man. And what about Kropotkin, that stellar

exemplar of humanity: Had he not defeated Huxley’s “gladiator” in Nature’s

glorious arena? Weren’t the fittest, after all, not the fiercest or the strongest but

those who acquired the habit of mutual aid and cooperation for the benefit of all?

16

Answering such questions in the affirmative, they suddenly felt like physicists.

They left freezing Minneapolis immeasurably more important than when they’d

arrived just two days before.

“How much is sixty million, five hundred and fifty-three thousand, eight hundred

and ninety-one divided by twenty-seven?”

“Two million, five hundred and one thousand, nine hundred and ninety-five point

ninety-six.”

“Good boy!”

Johnny von Neumann could divide eight-digit numbers in his head by the time he

was six. Visitors to the Budapest family home of the successful Jewish banker

Max Neumann were as stunned by his son’s ability to memorize phone books as

by the jokes he told in classical Greek. When he grew older he studied chemical

engineering, physics, and mathematics at Europe’s finest universities: Berlin,

Zurich, Budapest, Göttingen. Soon the word was out: Von Neumann was a

genius. By 1930, at twenty-six, he was sitting in the room next to Albert

Einstein’s at the Institute of Advanced Studies in Princeton. Einstein’s mind, they

said, was “slow and contemplative. He would think about something for years.

Johnny’s mind was just the opposite. It was lightning quick—stunningly fast. If

you gave him a problem he either solved it right away or not at all.”

17

Unsolvable problems were rare, though. Living with his wife, daughter, and an

Irish setter, Inverse, at a Princeton mansion on 26 Westcott Road, von Neumann

was famous for hosting lavish weekly alcohol-fuming parties, and even more for

scribbling mathematical formulas with pencil and paper in the middle of it

all—“the noisier,” his wife said, “the better.” He wore prim, vested suits with a

white handkerchief in the pocket, “an outfit just enough out of place to inspire

pleasantries.” Von Neumann was balding and porky; his diet consisted of yogurt

and hard-boiled eggs for breakfast and anything he wanted for the rest of the day.

He loved fast cars, hard liquor, classical music, and dirty jokes. He was a

prankster. Once he offered to take Einstein to the Princeton train station and then

put him on a train in the opposite direction. He was known for scribbling

equations on the blackboard in a frenzy, erasing them before students could get to

the end. Klara, his wife, claimed that he wouldn’t remember what he had for

lunch, but could recall word for word books he had read twenty years before. He

had produced groundbreaking papers in logic, set theory, group theory, ergodic

theory, and operator theory. He had described the single-memory architecture of

the modern computer, and performed the crucial calculation on the implosion

design of the atom bomb. Along side these accomplishments, he loved toys and

was observed unaffectedly scrapping with a five-year-old over a set of building

blocks on a carpet. Though he was charming and witty in public, few felt that they

really knew him well. People joked that John von Neumann was not human but a

demigod who could imitate humans precisely.

18

Above all he was fascinated by games, especially the kind, like poker, based on

bluffing and deceit. “It takes a Hungarian to go into a revolving door behind you

and come out first,” he used to say. In fact John von Neumann loved games so

much that he had decided to study them, seriously, as a mathematician. What he

discovered amazed him: In games where two opponents were in absolute conflict,

where the loss of one is the gain of the other and only one side can ever win; in

such “zero-sum” games there is always an optimal strategy for both players to

pursue. Tic-tac-toe is the simplest example, but here is an illustration from life:

Imagine two sweet-toothed kids being given a cake and told to share it. When a

grown up carefully divides the cake down the middle, one side always feels

slighted, even by a crumb. It is best for one of the kids to divide the cake, knowing

that the other can choose which piece he wants. Since both kids know that the

other wants as big a part of the cake as possible, cutting the cake precisely down

the middle is the optimal solution.

It was mathematically airtight. It applied to games that involved perfect

information (both kids know that the cake must be divided), complete self-interest

(both kids want as big a piece of the cake as possible), and rational decision

making based on a calculation of the other side’s agenda (the kid cutting the cake

understands that the other kid wants as big a piece as possible, and vice versa, and

both act accordingly). The issue was always how to maximize the minimum the

other side strove to leave you with, or, in other words, to minimize maximal

losses. The “minimax theorem” proved that there was always a best way to do

this. With the relevant information, the right strategy could be known.

19

The economists at Chicago had picked a hard time to wage their battle. In Europe

the Great War was now over, but Adolf Hitler had risen to become führer of

Germany, and Mussolini ruled with an iron fist in Italy. The Great Depression had

taken hold. Reeling citizens looked to their governments for salvation.

Enter John Maynard Keynes. “I have called this book the General Theory of

Employment, Interest and Money,” he wrote, Cambridge-style, in his magnum

opus in 1936,

placing the emphasis on the prefix general. The object of such a title is to contrast

the character of my arguments and conclusions with those of the classical theory

of the subject, upon which I was brought up and which dominates the economic

thought, both practical and theoretical, of the governing and academic classes of

this generation, as it has for a hundred years past. I shall argue that the

postulates of the classical theory are applicable to a special case only and not to

the general case, the situation which it assumes being a limiting point of the

possible positions of equilibrium. Moreover, the characteristics of the special

case assumed by the classical theory happen not to be those of the economic

society in which we actually live, with the result that its teaching is misleading

and disastrous if we attempt to apply it to the facts of experience.

20

If government didn’t intervene in the economy it would be betraying its citizens.

Since employment was not determined by the price of labor but by the spending

of money (what is called “aggregate demand”), the assumption that competition

will deliver full employment in the long run was patently false. On the contrary,

underemployment and underinvestment were the likely natural state of

competition; unless active measures were taken, that is. Lack of competition,

Keynes was arguing, was not the fundamental problem; the reduction of