Gregersen E. (editor) The Britannica Guide to Statistics and Probability

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

7 The Britannica Guide to Statistics and Probability 7

280

of the state in the economy and touched on the labour

theory of value.

Petty studied medicine at the Universities of Leiden,

Paris, and Oxford. He was successively a physician; pro-

fessor of anatomy at Oxford; professor of music in London;

inventor, surveyor, and landowner in Ireland; and a mem-

ber of Parliament. As a proponent of the empirical

scientific doctrines of the newly established Royal Society,

of which he was a founder, Petty was one of the originators

of political arithmetic, which he defined as the art of rea-

soning by figures upon things relating to government. His

Essays in Political Arithmetick and Political Survey or Anatomy

of Ireland (1672) presented rough but ingeniously calcu-

lated estimates of population and of social income. His

ideas on monetary theory and policy were developed in

Verbum Sapienti (1665) and in Quantulumcunque Concerning

Money, 1682 (1695).

Petty originated many of the concepts that are still

used in economics today. He coined the term full employ-

ment, for example, and stated that the price of land equals

the discounted present value of expected future rent on

the land.

siMéon-denis poisson

(b. June 21, 1781, Pithiviers, France—d. April 25, 1840, Sceaux)

The French mathematician Siméon-Denis Poisson was

known for his work on definite integrals, electromagnetic

theory, and probability.

Poisson’s family had intended him for a medical career,

but he showed little interest or aptitude and in 1798 began

studying mathematics at the École Polytechnique in Paris

under the mathematicians Pierre-Simon Laplace and

Joseph-Louis Lagrange, who became his lifelong friends.

281

7

Biographies 7

He became a professor at the École Polytechnique in 1802.

In 1808 he was made an astronomer at the Bureau of

Longitudes, and, when the Faculty of Sciences was insti-

tuted in 1809, he was appointed a professor of pure

mathematics.

Poisson’s most important work concerned the applica-

tion of mathematics to electricity and magnetism,

mechanics, and other areas of physics. His Traité de méca-

nique (1811 and 1833; “Treatise on Mechanics”) was the

standard work in mechanics for many years. In 1812 he

provided an extensive treatment of electrostatics, based

on Laplace’s methods from planetary theory, by postulat-

ing that electricity is made up of two fluids in which like

particles are repelled and unlike particles are attracted

with a force that is inversely proportional to the square of

the distance between them.

Poisson contributed to celestial mechanics by extend-

ing the work of Lagrange and Laplace on the stability of

planetary orbits and by calculating the gravitational

attraction exerted by spheroidal and ellipsoidal bodies.

His expression for the force of gravity in terms of the

distribution of mass within a planet was used in the late

20th century for deducing details of the shape of the

Earth from accurate measurements of the paths of orbit-

ing satellites.

Poisson’s other publications include Théorie nouvelle de

l’action capillaire (1831; “A New Theory of Capillary Action”)

and Théorie mathématique de la chaleur (1835; “Mathematical

Theory of Heat”). In Recherches sur la probabilité des juge-

ments en matière criminelle et en matière civile (1837; “Research

on the Probability of Criminal and Civil Verdicts”), an

important investigation of probability, the Poisson distri-

bution appears for the first and only time in his work.

Poisson’s contributions to the law of large numbers (for

7 The Britannica Guide to Statistics and Probability 7

282

independent random variables with a common distribu-

tion, the average value for a sample tends to the mean as

sample size increases) also appeared therein. Although

originally derived as merely an approximation to the bino-

mial distribution (obtained by repeated, independent

trials that have only one of two possible outcomes), the

Poisson distribution is now fundamental in the analysis of

problems concerning radioactivity, traffic, and the ran-

dom occurrence of events in time or space.

In pure mathematics his most important works were a

series of papers on definite integrals and his advances in

Fourier analysis. These papers paved the way for the

research of the German mathematicians Peter Dirichlet

and Bernhard Riemann.

adolphe queTeleT

(b. Feb. 22, 1796, Ghent, Belg.—d. Feb. 17, 1874, Brussels)

The Belgian mathematician, astronomer, statistician, and

sociologist Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet was known

for his application of statistics and probability theory to

social phenomena.

From 1819 Quetelet lectured at the Brussels Athenaeum,

military college, and museum. In 1823 he went to Paris

to study astronomy, meteorology, and the management

of an astronomical observatory. While there he learned

probability from Joseph Fourier and, conceivably, from

Pierre-Simon Laplace. Quetelet founded (1828) and

directed the Royal Observatory in Brussels, served as per-

petual secretary of the Belgian Royal Academy (1834–74),

and organized the first International Statistical Congress

(1853). For the Dutch and Belgian governments, he col-

lected and analyzed statistics on crime, mortality, and other

subjects and devised improvements in census taking. He

283

7

Biographies 7

also developed methods for simultaneous observations of

astronomical, meteorological, and geodetic phenomena

from scattered points throughout Europe.

In Sur l’homme et le développement de ses facultés, ou essai de

physique sociale (1835; A Treatise on Man and the Development

of His Faculties), he presented his conception of the homme

moyen (“average man”) as the central value about which

measurements of a human trait are grouped according to

the normal distribution. His studies of the numerical con-

stancy of such presumably voluntary acts as crimes

stimulated extensive studies in “moral statistics” and wide

discussion of free will versus social determinism. In trying

to discover through statistics the causes of antisocial acts,

Quetelet conceived of the idea of relative propensity to

crime of specific age groups. Like his homme moyen idea,

this evoked great controversy among social scientists in

the 19th century.

Jakob sTeineR

(b. March 18, 1796, Utzenstorf, Switz.—d. April 1, 1863, Bern)

The Swiss mathematician Jakob Steiner was one of the

founders of modern synthetic and projective geometry.

As the son of a small farmer, Steiner had no early

schooling and did not learn to write until he was 14. Against

the wishes of his parents, at 18 he entered the Pestalozzi

School at Yverdon, Switzerland, where his extraordinary

geometric intuition was discovered. Later, he went to the

University of Heidelberg and the University of Berlin to

study, supporting himself precariously as a tutor. By 1824

he had studied the geometric transformations that led

him to the theory of inversive geometry, but he did not

publish this work. In 1826 the first regular publication

devoted to mathematics, Crelle’s Journal, was founded,

7 The Britannica Guide to Statistics and Probability 7

284

giving Steiner an opportunity to publish some of his other

original geometric discoveries. In 1832 he received an hon-

orary doctorate from the University of Königsberg, and

two years later he occupied the chair of geometry estab-

lished for him at Berlin, a post he held until his death.

During his lifetime some considered Steiner the great-

est geometer since Apollonius of Perga (c. 262–190 BCE),

and his works on synthetic geometry were considered

authoritative. He had an extreme dislike for the use of

algebra and analysis, and he often expressed the opinion

that calculation hampered thinking, whereas pure geom-

etry stimulated creative thought. By the end of the century,

however, it was generally recognized that Karl von Staudt

(1798–1867), who worked in relative isolation at the

University of Erlangen, had made far deeper contributions

to a systematic theory of pure geometry. Nevertheless,

Steiner contributed many basic concepts and results in

projective geometry. For example, he discovered a trans-

formation of the real projective plane (the set of lines

through the origin in ordinary three-dimensional space)

that maps each line of the projective plane to one point on

the Steiner surface (also known as the Roman surface).

His other work was primarily on the properties of alge-

braic curves and surfaces and on the solution of

isoperimetric problems. His collected writings were pub-

lished posthumously as Gesammelte Werke, 2 vol. (1881–82;

“Collected Works”).

JaMes Joseph sylvesTeR

(b. Sept. 3, 1814, London, Eng.—d. March 15, 1897, London)

British mathematician James Joseph Sylvester, with Arthur

Cayley, was a cofounder of invariant theory, the study of

properties that are unchanged (invariant) under some

285

7

Biographies 7

transformation, such as rotating or translating the coordi-

nate axes. He also made significant contributions to

number theory and elliptic functions.

In 1837 Sylvester came second in the mathematical tri-

pos at the University of Cambridge but, as a Jew, was

prevented from taking his degree or securing an appoint-

ment there. The following year he became a professor of

natural philosophy at University College, London (the

only nonsectarian British university). In 1841 he accepted

a professorship of mathematics at the University of

Virginia, Charlottesville, U.S., but resigned after only

three months following an altercation with a student for

which the school’s administration did not take his side.

He returned to England in 1843. The following year he

went to London, where he became an actuary for an insur-

ance company, retaining his interest in mathematics only

through tutoring (his students included Florence

Nightingale). In 1846 he became a law student at the Inner

Temple, and in 1850 he was admitted to the bar. While

working as a lawyer, Sylvester began an enthusiastic and

profitable collaboration with Cayley.

From 1855 to 1870 Sylvester was a professor of mathe-

matics at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich. He

went to the United States once again in 1876 to become a

professor of mathematics at Johns Hopkins University in

Baltimore, Maryland. While there he founded (1878) and

became the first editor of the American Journal of

Mathematics, introduced graduate work in mathematics

into American universities, and greatly stimulated the

American mathematical scene. In 1883 he returned to

England to become the Savilian Professor of Geometry at

the University of Oxford.

Sylvester was primarily an algebraist. He did brilliant

work in the theory of numbers, particularly in partitions

7 The Britannica Guide to Statistics and Probability 7

286

(the possible ways a number can be expressed as a sum of

positive integers) and Diophantine analysis (a means for

finding whole-number solutions to certain algebraic equa-

tions). He worked by inspiration, and frequently it is

difficult to detect a proof in his confident assertions. His

work is characterized by powerful imagination and inven-

tiveness. He was proud of his mathematical vocabulary

and coined many new terms, but few have survived. In

1839 he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society, and he

was the second president of the London Mathematical

Society (1866–68). His mathematical output includes sev-

eral hundred papers and one book, Treatise on Elliptic

Functions (1876). He also wrote poetry, although not to crit-

ical acclaim, and published Laws of Verse (1870).

John von neuMann

(b. Dec. 28, 1903, Budapest, Hung.—d. Feb. 8, 1957, Washington,

D.C., U.S.)

Hungarian-born American mathematician John von

Neumann grew from a child prodigy to one of the world’s

foremost mathematicians by his mid-twenties. He pio-

neered game theory and, along with Alan Turing and

Claude Shannon, was one of the conceptual inventors of

the stored-program digital computer.

Von Neumann showed signs of genius in early child-

hood: He could joke in Classical Greek and, for a family

stunt, he could quickly memorize a page from a telephone

book and recite its numbers and addresses. Upon comple-

tion of von Neumann’s secondary schooling in 1921, his

father discouraged him from pursuing a career in mathe-

matics, fearing that there was not enough money in the

field. As a compromise, von Neumann simultaneously

studied chemistry and mathematics. He earned a degree

287

7

Biographies 7

in chemical engineering (1925) from the Swiss Federal

Institute in Zürich and a doctorate in mathematics (1926)

from the University of Budapest.

Von Neumann commenced his intellectual career

when the influence of David Hilbert and his program of

establishing axiomatic foundations for mathematics was

at a peak, working under Hilbert from 1926 to 1927 at the

University of Göttingen. The goal of axiomatizing math-

ematics was defeated by Kurt Gödel’s incompleteness

theorems, a barrier that Hilbert and von Neumann imme-

diately understood. The work with Hilbert culminated in

von Neumann’s book The Mathematical Foundations of

Quantum Mechanics (1932), in which quantum states are

treated as vectors in a Hilbert space. This mathematical

synthesis reconciled the seemingly contradictory quan-

tum mechanical formulations of Erwin Schrödinger and

Werner Heisenberg.

In 1928 von Neumann published “Theory of Parlor

Games,” a key paper in the field of game theory. The

nominal inspiration was the game of poker. Game theory

focuses on the element of bluffing, a feature distinct from

the pure logic of chess or the probability theory of rou-

lette. Though von Neumann knew of the earlier work of

the French mathematician Émile Borel, he gave the sub-

ject mathematical substance by proving the mini-max

theorem. This asserts that for every finite, two-person

zero-sum game, there is a rational outcome in the

sense that two perfectly logical adversaries can arrive

at a mutual choice of game strategies, confident that

they could not expect to do better by choosing another

strategy. In games like poker, the optimal strategy incor-

porates a chance element. Poker players must bluff

occasionally—and unpredictably—to avoid exploitation

by a savvier player.

7 The Britannica Guide to Statistics and Probability 7

288

In 1933 von Neumann became one of the first professors

at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), Princeton, N.J.

The same year, Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany, and

von Neumann relinquished his German academic posts.

Although Von Neumann once said he felt he had not

lived up to all that had been expected of him, he became a

Princeton legend. It was said that he played practical jokes

on Einstein and could recite verbatim books that he had

read years earlier. Von Neumann’s natural diplomacy

helped him move easily among Princeton’s intelligentsia,

where he often adopted a tactful modesty. Never much

like the stereotypical mathematician, he was known as a

wit, bon vivant, and aggressive driver—his frequent auto

accidents led to one Princeton intersection being dubbed

“von Neumann corner.”

In late 1943 von Neumann began work on the Manhattan

Project, working on Seth Neddermeyer’s implosion design

for an atomic bomb at Los Alamos, N.M. This called for a

hollow sphere containing fissionable plutonium to be sym-

metrically imploded to drive the plutonium into a critical

mass at the centre. The implosion had to be so symmetri-

cal that it was compared to crushing a beer can without

splattering any beer. Adapting an idea proposed by James

Tuck, von Neumann calculated that a “lens” of faster- and

slower-burning chemical explosives could achieve the

needed degree of symmetry. The Fat Man atomic bomb

dropped on Nagasaki used this design.

Overlapping with this work was von Neumann’s mag-

num opus of applied math, Theory of Games and Economic

Behavior (1944), cowritten with Princeton economist

Oskar Morgenstern. Game theory had been orphaned

since the 1928 publication of “Theory of Parlor Games,”

with neither von Neumann nor anyone else significantly

developing it. The collaboration with Morgernstern

289

7

Biographies 7

burgeoned to 641 pages, the authors arguing for game

theory as the “Newtonian science” underlying economic

decisions. The book invigorated a vogue for game theory

among economists that has partly subsided. The theory

has also had broad influence in fields ranging from evolu-

tionary biology to defense planning.

Starting in 1944, he contributed important ideas to the

U.S. Army’s hard-wired Electronic Numerical Integrator

and Computer (ENIAC) computer. Most important,

von Neumann modified the ENIAC to run as a stored-

program machine. He then lobbied to build an improved

computer at the Institute for Advanced Studies (IAS). The

IAS machine, which began operating in 1951, used binary

arithmetic (the ENIAC had used decimal numbers) and

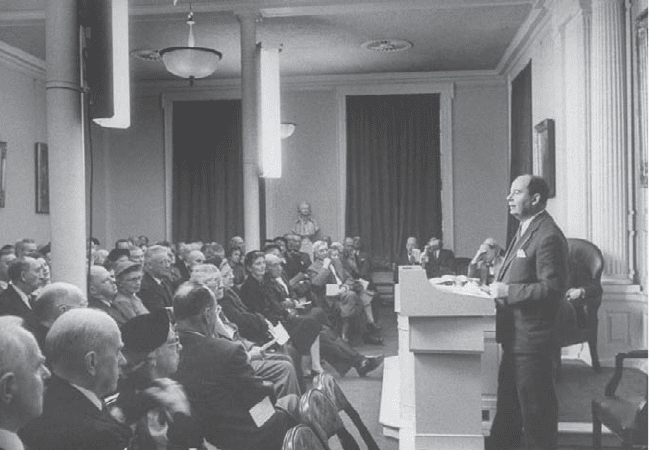

John von Neumann pioneered game theory, contributed to the infamous

Manhattan Project, and was one of the conceptual inventors of the stored-

program digital computer. Alfred Eisenstaedt/Time & Life Pictures/

Getty Images