Goldfarb D. Biophysics DeMYSTiFied

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

182 Biophysics DemystifieD

You should keep in mind, however, that these structures are not, by any

means, the only stuff inside the cell. In addition to the organelles listed below,

the inside of the cell is a densely populated environment with hundreds, if not

thousands, of different types of molecules. These include water, dissolved gasses

such as oxygen and carbon dioxide, structural proteins, enzymes, nucleic acids,

lipids, various ions (sodium, calcium, magnesium, potassium, chloride, phos-

phate, etc.), minerals, vitamins, sugars and other nutrients and all the building

blocks of these molecules, for example, nucleotides, small polypeptides, amino

acids, and a whole host of small organic molecules that are part of the thou-

sands of biochemical reactions and biophysical processes continually happening

inside the cell.

The amount of each type of molecule inside a cell varies widely, anywhere

from a few copies for some molecules to hundreds of millions for others. Alto-

gether, depending on the size and type of cell, a typical single cell may be made

up of anywhere from hundreds of billions to tens of trillions of molecules.

Taken together, everything inside the cell (other than the cell membrane) is

called the cytoplasm; this includes all of the structures listed in the following

sections, plus all of the molecules floating around inside the cell (some of which

were just listed).

DNA

DNA is perhaps the largest and certainly the most significant of structures

inside the cell. The cell’s DNA is its genetic material, the instructions passed

down from generation to generation for building all of the proteins in the cell,

which in turn do the work of building, mediating or getting involved in pretty

much everything else in the cell. The DNA in the cell is organized into struc-

tures called chromosomes. Each chromosome is a single DNA molecule that has

been packaged and organized in a specific way. Sometimes the DNA is orga-

nized into complexes with other molecules such as proteins. This is typically

the case with most DNA in eukaryotes. In prokaryotes the DNA may be pack-

aged by coiling it up tightly.

At certain stages of a cell’s life cycle, the DNA is more spread out, like a plate

of spaghetti, and individual chromosome structures are not apparent. In this state,

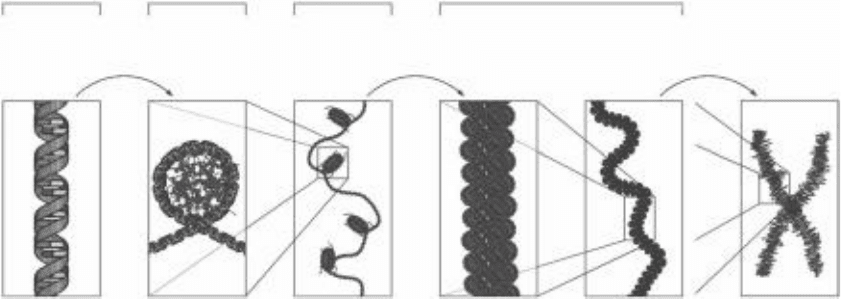

the DNA is referred to as chromatin. See Fig. 8-6. All of a cell’s chromosomes, or

all of a cell’s chromatin, taken together as a whole is called the cell’s genome.

Prokaryotes almost always contain only one chromosome, a single DNA mol-

ecule. That’s the entire prokaryotic genome, just one chromosome. In prokary-

otes, the ends of this single DNA molecule are covalently connected to one

chapter 8 The cell 183

another, making the chromosome one big DNA circle. This DNA circle is usually

so long and thin that, although it’s a circle, it still resembles a plate of spaghetti.

The Cytoskeleton

Cells contain many fibrous structures which together are called the cytoskeleton.

These tubelike and ropelike structures are often interconnected, and play a

number of roles in which they support, transmit, or apply forces, in much the

same way that bones support, transmit, and apply forces for the body (thus the

term skeleton). Among other things, the cytoskeleton helps to support and

maintain a cell’s shape, it transmits and applies forces for cellular movement,

and it helps anchor various organelles into place within the cell. Both eukary-

otes and prokaryotes have a cytoskeleton.

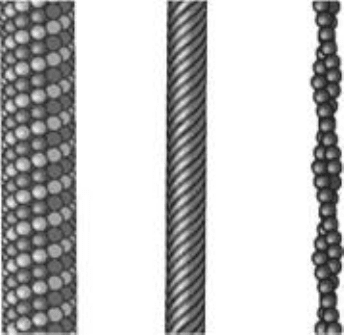

Cytoskeleton fibers are made of polymerized protein molecules. (Remember,

proteins are themselves polymers of amino acids, so the cytoskeleton fibers are

polymers where each residue is itself a folded up polymer.) There are three

types of cytoskeleton fibers, classified according to their size and shape: micro-

tubules, intermediate filaments, and microfilaments.

Microtubules are the largest, about 25 nm in diameter. They are long tubelike

structures made up from the protein tubulin. There are two types of tubulin:

a-tubulin and b-tubulin. One a-tubulin molecule and one

b-tubulin molecule

combine to form a dimer ( a polymer of two molecules). The tubulin dimers then

DNA The nucleosome

“Beads-on-a-String” The 30-nm fiber

Add further scaffold proteins.Add histone H1.Add core histones.

FIgure 8-6 • Structure of eukaryotic chromatin. A nucleosome is a DNA double helix wrapped around a cluster of

proteins called a histone. Since the DNA helix is itself wrapped into the shape of a coil or helix, this configuration is

called a supercoil or superhelix. Nucleosomes are then further packaged together with protein histone H1 to create

30-nm fibers of chromatin. These are further packaged with other scaffolding proteins to make a chromosome

structure. (Figure derived from Wikimedia Commons.)

184 Biophysics DemystifieD

polymerize end to end, with the a-tubulin from one dimer connecting to the

b-tubulin from the next. This creates what is called a protofilament. The protofila-

ments then bundle together, to form a strong tubelike structure. See Fig. 8-7.

Intermediate filaments and microfilaments are also polymers of proteins, just

different proteins, for example, the proteins actin or keratin. Also, as their names

imply, intermediate and microfilaments are not tubelike. Instead their protofila-

ments combine to form structures similar to a twisted cable or rope.

As mentioned, one of the roles of the cytoskeleton is in movement. The

cytoskeleton is involved both in moving things around inside the cell and in

moving the cell itself. This is a fascinating area of biophysics. The cytoskeleton

generates forces for movement through the polymerization (or depolymeriza-

tion) process. As residues are added to or removed from one end of a cytoskel-

eton fiber, then as the fiber grows or shrinks, it pushes or pulls whatever is

attached to the other end. So, for example, if a part of the membrane is attached

to the other end, the cytoskeleton can generate the forces needed to bend the

membrane during endocytosis.

Ribosomes

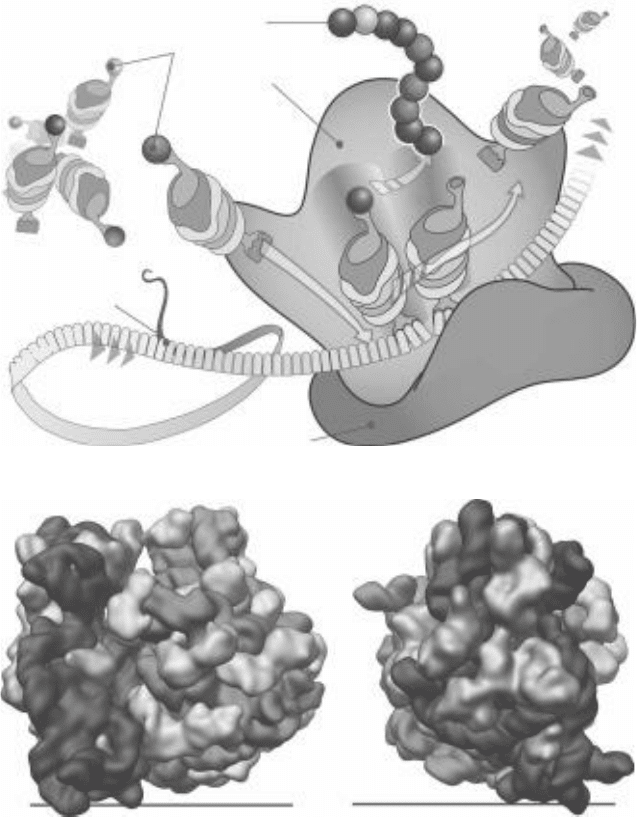

Both eukaryotes and prokaryotes contain large complex structures called ribosomes.

A ribosome is a complex of structural proteins, enzymes, and ribosomal RNA (rRNA).

Ribosomes are factories where protein synthesis takes place. (See Chap. 7, the section

Nucleic Acid Function, for a description of protein synthesis.) The ribosome is the

FIgure 8-7 • Illustration of cytoskeleton fibers,

from left to right: microtubules, intermediate

filaments, and microfilaments.

chapter 8 The cell 185

place where the messenger RNA, the transfer RNA, and the amino acid all get

together. The ribosome ensures that these three things work together in just the right

way needed to polymerize the amino acids according to the sequence specified by

the mRNA. See Fig. 8-8 for illustration. There is evidence that some of the catalytic

(enzymatic) activity needed to synthesize proteins comes not only from the ribo-

somal proteins but also from the ribosomal RNA.

Large subunit

tRNA

mRNA

Small subunit

A site

P site

Amino acids

Newly born protein

(a)

200 Å 200 Å

(b)

FIgure 8-8 • (a) Illustration of ribosome and its role in protein synthesis. (b) Computer-

generated front and side view of a ribosome, from the bacteria, Escherichia coli. (Courtesy

of Wikimedia Commons.)

186 Biophysics DemystifieD

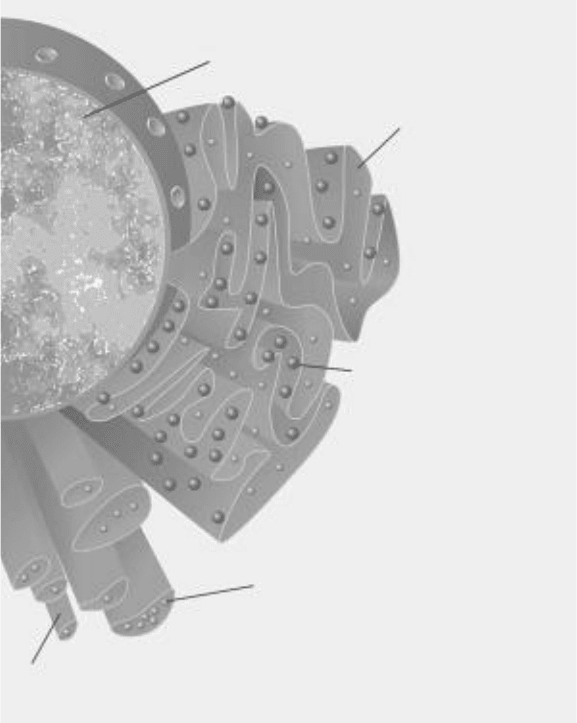

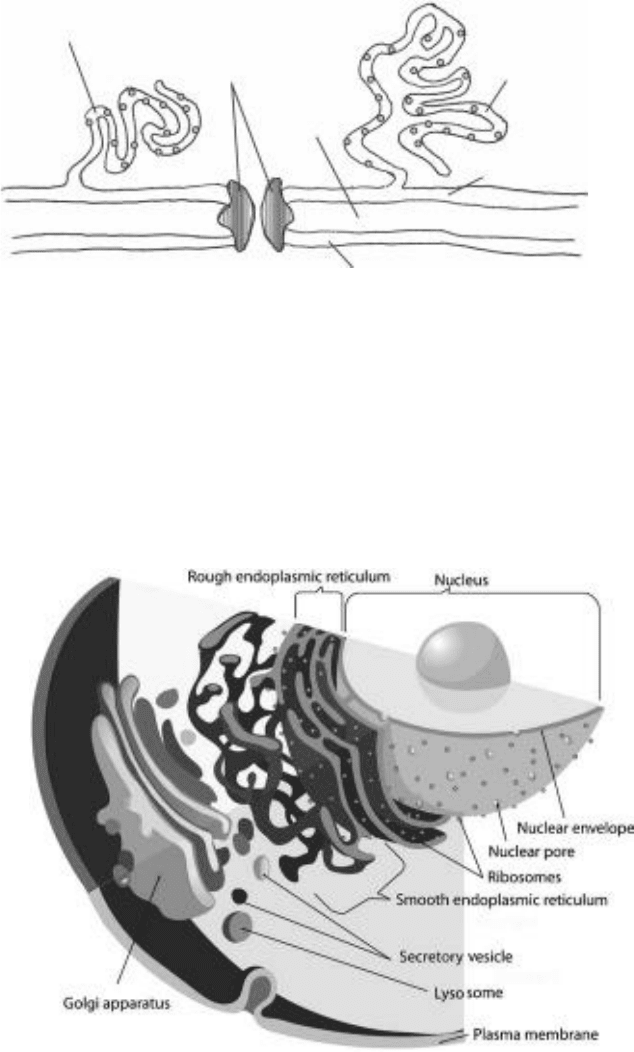

Endoplasmic Reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a network of folded membranes found inside

eukaryotic cells. The ER is similar to the plasma membrane in that it is a phos-

pholipid bilayer with various other molecules embedded within it. However,

the ER is a folded membrane that doesn’t actually surround anything. Rather it

provides a network of membrane surfaces and pathways between them. See

Fig. 8-9. In general in cells, wherever we find folded membranes, we find many

biophysical and biochemical processes associated with the membrane. The fold-

ing of the membrane creates a much larger membrane surface (for a given

amount of volume) to facilitate these processes.

Ribosome

Lipid vesicle

Smooth endoplasmic reticulum

Rough endoplasmic reticulum

Nucleus

FIgure 8-9 • Endoplasmic reticulum. (Derived from Wikimedia Commons.)

chapter 8 The cell 187

There are two types of endoplasmic reticulum, smooth and rough; the main

difference is that the rough ER has ribosomes on its surface. The rough ER is

involved in protein synthesis, whereas the smooth ER is involved in lipid and

steroid synthesis. Both types of ER are also involved to some extent in addi-

tional processing of molecules, for example, adding carbohydrates to proteins

to form glycoproteins, splicing and folding of polypeptide chains as part of

protein formation, and packaging of proteins and other molecules into lipid

vesicles for transport to other parts of the cell.

Nucleus

The nucleus is an approximately spherical membrane-bound (membrane-

surrounded) organelle near the center of eukaryotic cells. The nucleus contains

almost all of the cell’s genome. (Some genetic material is also found in mito-

chondria.) The main functions of the nucleus are gene expression (transcription

of genes into RNA to make proteins) and DNA replication (copying of the

genome just prior to cell division). The nucleus is often referred to as the con-

trol center of the cell. This is because the nucleus controls the expression of

almost all of the cell’s genes, which in turn control the manufacture of the cell’s

proteins, which in turn are involved in virtually every biochemical and bio-

physical process inside the cell.

The nucleus is surrounded by a double membrane called the nuclear envelope

or nuclear membrane. By double membrane, we mean that it consists of two

membranes, each of which is itself a lipid bilayer (with various other molecules

embedded in it). The space between the inner nuclear membrane and the outer

nuclear membrane is called the perinuclear space. The outer nuclear membrane

is contiguous (directly connected to) to the membrane of rough endoplasmic

reticulum. This connection helps facilitate protein synthesis which occurs on

the rough ER since it is directly dependent on the transcription of genes into

mRNA, tRNA, and rRNA in the nucleus. Along the nuclear membrane are

special proteins called nuclear pores. Nuclear pores are membrane transport

proteins that span both membranes of the nucleus and control the flow of mol-

ecules into and out of the nucleus. See Fig. 8-10. Just inside the inner nuclear

membrane is the nuclear lamina, a network of intermediate filaments that plays

a role similar to the cytoskeleton. The nuclear lamina provides mechanical sup-

port, aids in transport of molecules to and from nuclear pores, and is involved

in organizing chromatin. It also helps separate chromosome copies during cell

division to ensure that each daughter cell gets its own copy of each

chromosome.

188 Biophysics De mystifieD

Endomembrane System

In addition to the endoplasmic reticulum, there are a number of membranous organ-

elles that work together in eukaryotic cells. Together, these organelles are called the

endomembrane system. Figure 8-11 illustrates the endomembrane system.

Nucleus

Inner nuclear membrane

Outer nuclear membrane

Rough

endoplasmic

reticulum

Perinuclear

space

Rough

endoplasmic

reticulum

Nuclear pore

FIgure 8-10 • Nuclear envelope.

FIgure 8-11 • Endomembrane system.

chapter 8 The cell 189

Golgi Apparatus

One of the larger organelles in the endomembrane system is the Golgi appara-

tus, also called the Golgi complex or Golgi body. The Golgi apparatus is very

similar to smooth ER in that it is a folded membrane involved in processing and

packaging of large molecules such as proteins and lipids. Many molecules man-

ufactured and processed in the ER are later passed on to the Golgi apparatus

for further processing and for packaging to be transported outside the cell. In

addition, Golgi bodies are involved in the breakdown of carbohydrates and

lipids so that the parts can be used in other processes inside the cell. The Golgi

apparatus is named for Camillo Golgi who discovered it in 1898.

Vesicles

Vesicles are small, approximately spherical lipid bilayer containers. They typically

result from a portion of some larger membrane structure budding out and being

pinched off. In the process of budding out and being pinched off, various mole-

cules (proteins, etc.) become trapped inside the vesicle. The contents of the ves-

icle can then be transported to other locations. Vesicles also commonly reverse

the process, by fusing with other membrane structures and releasing their con-

tents at the same time. When the vesicles fuse with or bud from the plasma

membrane, these processes are called endocytosis and exocytosis (see earlier in this

chapter). However, vesicle budding and vesicle fusion also occur frequently with

other membranous structures such as the ER and Golgi apparatus.

Some types of vesicles are given specific names related to their contents and

function. For example, lysosomes are vesicles that contain enzymes (called lysozymes)

that specialize in breaking down or digesting larger molecules. In this way the

somewhat harsh environment needed to digest larger molecules is isolated inside

the lysosome to protect other molecules inside the cell. Peroxisomes are similar to

lysosomes, but specialize in the breakdown of long chain fatty acids.

Vacuoles

Vacuoles are, in a sense, giant vesicles. They are often made from many vesicles

that have fused together. Vacuoles have no particular shape. They are found in

all plant cells and in some animal and bacteria cells. They serve a variety of

functions, but are most commonly involved in isolating things that might oth-

erwise be harmful for the cell and in containing and eliminating waste products

(i.e., exporting waste from the cell via exocytosis). They are also involved in

maintaining correct hydrostatic pressure inside the cell and using that pressure

to support plant structures such as flowers and leaves.

190 Biophysics DemystifieD

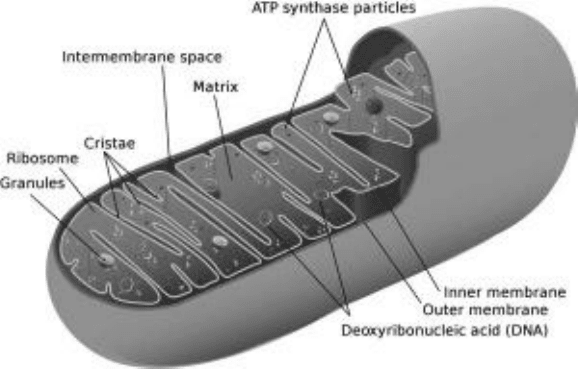

Mitochondria

Mitochondria (singular mitochondrion) are membrane-bound organelles in most

eukaryotic cells. Their main job is the synthesis of ATP (adenine triphosphate)

which is used as the energy currency for many biophysical processes inside the

cell. In this way mitochondria convert the energy stored in food into high-energy

phosphate bonds of ATP. It is because of this role of mitochondria that they are

sometimes called the power plants of the cell. Figure 8-12 illustrates the struc-

ture of a mitochondrion. There is an outer membrane and a folded inner mem-

brane. The membrane folds that reach in toward the center of the mitochondrion

are called cristae. The folded inner membrane supports the synthesis of ATP.

Mitochondria also contain DNA. The DNA molecules in mitochondria

are small circular molecules. By small, we mean approximately 15 thousand

base pairs long (as compared to about 1 million base pairs for a typical bac-

terial genome and about 3 billion base pairs in the human genome). There

are typically 2 to 10 DNA molecules per mitochondrion. Mitochondrial

DNA (mtDNA) replicates independently of the DNA in the nucleus. While

the vast majority of proteins found in mitochondria are coded for by nuclear

DNA, some of the proteins and RNA found in mitochondria are coded for

by the mtDNA. For example, there are 37 genes in human mtDNA. Of

these, 22 code for transfer RNA, 13 genes code for proteins, and 2 code for

ribosomal RNA.

FIgure 8-12 • Mitochondrion.

chapter 8 The cell 191

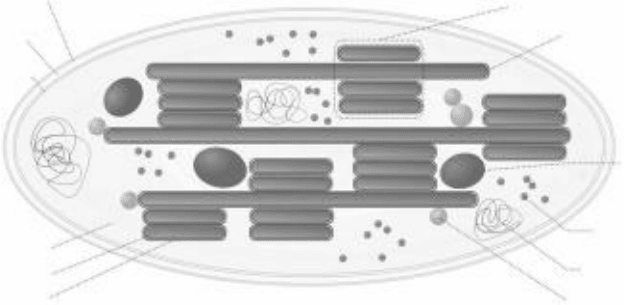

Chloroplasts

Chloroplasts are organelles found in the cells of plants and a few other eukary-

otes. They are found mostly in the cells of leaves and other green portions of

plants. Chloroplasts carry out the process of photosynthesis, which is the capture

of energy from light and the conversion of that energy into the chemical bond

energy of carbohydrates. This is how plants manufacture food from light and

carbon dioxide. (Some bacteria also carry out photosynthesis, but they do so

without chloroplasts which are only found in eukaryotes.)

Chloroplasts contain an outer membrane and an inner folded membrane. See

Fig. 8-13.

The inner folded membrane forms a series of disklike or cylindrical struc-

tures called thylakoids. It is within the membranes of the thylakoids where

photosynthesis takes place. As we saw with other organelles, membrane folding

increases the surface area over which biophysical processes can take place. In

the case of chloroplasts, this increases absorption of light for photosynthesis.

Membrane proteins in the thylakoids form a complex with a class of molecules

called chlorophylls. Chlorophylls absorb light and, together with the membrane

proteins in the thylakoids, convert the light energy into the high-energy bonds in

ATP and the chemical bond energy of carbohydrates (sugars and starches). The

process requires that a magnesium ion be bound to the chlorophyll (as shown in

Fig. 8-14). Several different types of chlorophylls are known. The most common

and universal is chlorophyll a. Others include chlorophyll b, c1, c2, and d. The dif-

ferent chlorophylls absorb light of different wavelengths, but for the most part they

DNA

Lipid vesicle

Ribosome

Thylakoid (lamella)

Starch

Granum (stack of thylakoids)

Outer membrane

Intermembrane

space

Inner membrane

Stroma

(aqueous fluid)

Thylakoid

Thylakoid

membrane

(carbohydrate)

FIgure 8-13 • Chloroplast. (Derived from Wikimedia Commons.)