Fouracre P. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 1: c. 500-c. 700

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Mediterranean economy 633

civil war, the mutually destructive conflict with Persia, and the Arab conquests,

brought in its train a profound restructuring of the eastern Mediterraneanecon-

omy.

94

Its most significant effect was to impose the regionalisation of exchange

that was already characteristic of the West. In Byzantine-held territories this

seems to have coincided with widespread and relatively radical changes in the

organisation of production and perhaps also in the tastes of consumers. The

manufacture of PRS, for example, came to an abrupt end around the mid-

seventh century, superseded around Constantinople by Glazed White Wares;

these belong to a different ceramic tradition, and they initially enjoyed a more

limited distribution.

95

In the territories conquered by the Arabs, however, there

was no dramatic transformation of ceramic styles; in Palestine and Jordan, for

example, production of existing regional fine wares continued, and if anything

their quality improved. Indeed, the archaeological evidence for settlement and

production suggests that catastrophist interpretations of the Arab impact are

seriously misplaced.

96

As in the case of Vandal Africa in the fifth century,

there is no neat coincidence here between political and economic change, and

no necessary cessation of traffic between conquered and imperially held ter-

ritory. In his eye-witness account of his visit to the holy places in the 680s,

the pilgrim Arculf mentions an annual fair in Jerusalem attended by ‘a throng

beyond number of all races from almost everywhere’.

97

Even so, the various

regional varieties of Red Slip did eventually go out of production, and while

amphorae from these regions were still manufactured, they ceased to be widely

distributed overseas, and were very slowly superseded by alternative types of

container. Only in Egypt would the late antique ceramic tradition represented

by local Red Slip wares and late Roman amphora types persist for centuries

to come.

98

By the eighth century the polyfocal exchange-system of the east-

ern Mediterranean had disintegrated, leaving in its wake the series of regional

economies which had always existed. Some of these were well developed, espe-

cially those of Syria and Egypt, but there seems to have been much less over-

lap between them than before, and they were no longer oriented towards

the Mediterranean.

In the western Mediterranean,meanwhile, there was no such radical seventh-

century interruption to existing trends. The interregional tier of the economy

continued to dwindle away, and no new networks of overseas exchange were

yet emerging to replace it. But recent excavations have implied that its twilight

lingered far longer than had previously been thought. In Africa production

94

Haldon (1990) and (2000).

95

Hayes (1992), pp. 12–34.

96

Sodini and Villeneuve (1992); Watson (1992); Schick (1998); Walmsley (1996) and (2000).

97

Adomn

´

an, De Locis Sanctis i.7;cf. Arthur and Oren (1998) for the persistence of imports from Africa

and other eastern regions to Egypt through the seventh century, long after the Arab conquest.

98

Walmsley (2000), pp. 317–31, for slow change in Syria; Bailey (1998), pp. 8–58 for Egypt.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

634 s. t. loseby

of an attenuated range of pottery, lamps and amphorae continued up to and

beyond the Arab conquest.

99

Meanwhile, a select but increasing number of

western Mediterranean sites are now known to have gone on receiving imports

from both Africa and the East, in some cases throughout the seventh cen-

tury. In the south of France, for example, Marseilles had from the sixth cen-

tury resumed its pre-Roman role as an emporium mediating Mediterranean

exchange with north-western Europe. Although the port was clearly in decline

by the late seventh century, an assortment of African ceramics and a few east-

ern amphorae of various types were still arriving, showing not only that the

interregional circulation of pottery and foodstuffs persisted, but also that it

was by no means confined to the remaining western outposts of imperial

authority.

100

At Rome, two substantial and closely dated ceramic assemblages from the

Crypta Balbi, a site plausibly associated in this period with the monastery of

S. Lorenzo in Pallacinis, seem to mark the final eclipse of the ancient Mediter-

ranean economic system.

101

In the first, dating from c.690, ARS was almost

the only fine ware present, but the common wares, though mostly local, also

included a scatter of African and eastern imports.

102

The amphora assemblage

was also dominated by African models, but it also included a wide variety

of eastern imports, containers from southern Italy, and a significant number

and proportion of unknown types, which, whatever their origin, can only

imply greater diversity and complexity of exchange (Map 16). The second

deposit from the same site, dating from perhaps c.720, offers an immediate

and startling point of comparison. It contains neither ARS nor any of the stan-

dard African or eastern late antique amphora types. Instead, all the identifiable

amphorae were manufactured in southern and central Italy. Indeed, the overall

proportion of amphora sherds in the ceramic assemblage falls from 46 per cent

to 25 per cent, perhaps reflecting this decline in imports, or more likely increas-

ing resort to other forms of container.

103

Whereas around 80 per cent of the

ceramics in the late seventh-century deposit were imported from outside Italy,

hardly any of the pottery in the later assemblage came from further afield than

Sicily. It appears that while Rome still needed imports, it was acquiring them

99

Mackensen (1993), esp. pp. 493–4;Reynolds (1995), pp. 31–4, 57–60;BenAbed et al.(1997).

100

Bonifay and Pieri (1995); Bonifay et al.(1998), esp. pp. 357–8; Loseby (1998) and (2000). Cf.

Mannoni, Murialdo et al.(2001), for later seventh-century material at S. Antonino di Perti in

Liguria.

101

Sagu

`

ı, Ricci and Romei (1997); Sagu

`

ı(1998a); Bacchelli and Pasqualucci (1998); Ricci (1998).

102

For the low-level circulation of common wares around the Mediterranean in our period, a further

marker of economic integration, see e.g. Reynolds (1995), pp. 86–105.

103

Arthur (1989) and (1993) for observations on the decline of the amphora in Italy; Hayes (1992),

pp. 61–79, for later medieval amphora series at Constantinople.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Mediterranean economy 635

closer to home, and stimulating the regional economy into new and diverse

forms of production in the process.

104

It is obviously simplistic to place too much emphasis on a single site, or,

more generally, to suggest that the ramifications of the Mediterranean economy

can be entirely deduced from ceramic distributions. But the archaeological

evidence from the Crypta Balbi, and from the small but increasing number of

other sites where seventh-century deposits have been recovered, is increasingly

consistent with the conclusions about the timing of the end of the ancient

exchange-system drawn by some scholars from the more impressionistic, but

also more multifaceted indications of the written sources. Most famously, as

we saw at the beginning of this chapter, Henri Pirenne had argued that it was

not the barbarian invasions of the fifth century, but the Arab conquests of

the seventh which had destroyed the Roman economic legacy.

105

His use of

evidence was selective, and his reasoning seriously flawed, but his chronology

deserves to be taken seriously. Indeed, in his much more thorough analysis

of the documentary evidence for western Mediterranean trade in the early

Middle Ages, Dietrich Claude inclined cautiously towards a similar date for

the nadir of Mediterranean trade, in the period between the late seventh and

the middle of the eighth century.

106

ButPirenne’s monocausal explanation of

this phenomenon in terms of the rise of Islam will not do. It had certainly

not been business as usual in the West until the later seventh century. In

the East, meanwhile, the Arab conquests are but one element in a radical

transformation of the internal structures of the Byzantine Empire, now greatly

diminished in extent, and, with the loss of its richest provinces, even more

so in resources. The grip of the state on remaining surplus production was

tightened as a result and, once its links with Carthage were definitively broken,

Constantinople fell back upon the Black Sea and the northern Aegean for

supplies.

107

In the areas newly conquered by the Arabs, in contrast, change

was more evolutionary in character. Even so, evidence for the participation

of these regions in Mediterranean exchange does gradually diminish, whether

because of the nature of the Umayyad state, devolving power and taxation to

the regional level, or perhaps because of the reorientation of the main flows

of exchange eastwards towards Mesopotomia and the Indian Ocean.

108

The

Mediterranean never became a barrier, as Pirenne had claimed, but no longer

did it serve as the primary focus of interregional exchange for the Byzantine or

the Arab lands around it.

104

Marazzi (1998a).

105

Pirenne (1939).

106

Claude (1985), p. 303.

107

Haldon (2000), esp. pp. 255–60.

108

See note 96, above, with Kennedy (1995) for the Umayyad state.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

636 s. t. loseby

Back in the western Mediterranean,the contrast in the two assemblages from

the Crypta Balbi offers an unusually stark and late illustration of the breakdown

in the late antique exchange-network, which had progressively affected all com-

munities around its shores from the fifth century onwards. Within our period

the imported ceramics which representour clearest markers of engagement with

interregional exchange had receded first from the hinterlands of the Mediter-

ranean, then from some coastal regions, and ultimately even from Rome itself.

The reasons for this contraction are many and varied, but its gradual nature, the

absence of any clear indications of generalised technological or environmental

change, and the telling failure of any new networks of interregional exchange to

emerge over the period all suggest that the explanation is essentially structural.

In the third century, rural Italian peasants could both afford and acquire ARS;

in the seventh they could not. On the supply side, the absolute quantities of

ARS in circulation were almost certainly declining, political disaggregation had

ended or restricted the underpinning of distribution networks by the state, and

the integration of the regional market economy which permitted the circula-

tion inland of imported goods had in places been undermined by protracted

periods of warfare, most obviously in Italy. On the demand side, it is likely that

the needs of the state were greatly reduced, and that many private consumers

were increasingly impoverished, in some regions to such an extent that even

regional economic systems were undermined, and exchange contracted to a

rudimentary level.

109

The basic tax-and-spend dynamic of the Roman state

was primarily concerned with ensuring its own survival, but it had inciden-

tally provided mechanisms which both enabled and encouraged peasants to

convert tiny agricultural surpluses into profit, purchasing-power and material

wealth. The Roman economy was nowhere near as state-directed as has some-

times been supposed, but in some important respects it was state-inspired. This

meant that the collapse of imperial control in the West could not destroy the

economy, but it could gradually undermine it. The combination of reduced

production, an increase in the cost or difficulty of distribution, and declining

demand was corrosive; as consumers became poorer, so imports became scarcer

and more expensive. A mass-produced, widely diffused commodity like ARS

was progressively transformed into a luxury item.

Although the interregional tier of the exchange-network survived in some

form in the western Mediterranean until the end of our period, therefore, it

had become more of a cultural than an economic phenomenon. The reduction

in the range of available manufactures of African goods suggests that produc-

tion was in decline, but the distribution pattern confirms that they were still

notionally available around the Mediterranean well into the seventh century.

109

Wickham (1998) offers an alternative hierarchy of explanation, emphasising demand.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Mediterranean economy 637

The problem was that they were no longer so readily affordable. The reach of

the Mediterranean economy recedes, not just geographically, but also socially,

and perhaps politically. The Crypta Balbi excavations show that as long as

interregional exchange continued to exist, some people in Rome were served

by it. Their privileged access to imports is perhaps the result of state-directed

exchange, but the continuing availability of a wide range of overseas goods

in the Provenc¸al ports shows that such traffic was also commercial, and not

confined to Byzantine-held regions. Indeed, the determination of Merovingian

kings to organise the redistribution of the remarkable range of Mediterranean

imports mentioned in the Corbie diploma to their chosen beneficiaries, the

expense of inland transport notwithstanding, shows how the elites of the north-

ern world had remained almost touchingly devoted to certain deeply ingrained

habits derived from antiquity: churches illuminated by oil lamps rather than

wax candles, charters written on Egyptian papyrus rather than parchment, food

flavoured with exotic spices, and perhaps still washed down by the occasional

beaker of powerful Gaza wine. All this forms the material equivalent of, for

example, respect for Roman administrative practices, and illustrates the endur-

ing appreciation of late antique and Byzantine cultural norms among western

elites. In Francia all this was a matter of choice, not of economic necessity, and

it continued until the supply of such imports finally dried up.

110

In Rome, any

crisis the end of African and eastern imports caused was soon met by a rapid

restructuring of the economy to establish regular regional networks of supply.

Butnowhere in the West was demand sufficient to necessitate interregional

exchange. Only the Roman world-system had made a Mediterranean economy

essential, and only a community of taste had sustained it through to the end

of our period as a cultural phenomenon.

111

At privileged western sites like Rome and Marseilles,or Carthage and Naples,

the archaeological evidence suggests that the late antique exchange-network

persisted in an etiolated form through to the close of the seventh century. Until

then, indeed, many of the essential features of the Mediterranean economy −

the main exporting regions, the types of pottery and amphorae in overseas cir-

culation, some of the major flows of exchange − were still recognisably those of

500.But over the intervening period the whole system had relentlessly declined

in the West, such that participation in interregional exchange gradually became

the exception rather than the norm. In the East, the collapse of this tier of the

economy was both more sudden and more complex, but the outcome was

similar. Some trading-ships continued to ply the Mediterranean in the eighth

century, and some regional economies around its shores were thriving, although

110

Loseby (2000), pp. 189–93.For lighting practices, Fouracre (1995), pp. 68–78.

111

For the Roman Empire as world-system, Woolf (1990).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

638 s. t. loseby

others, for example those of southern Francia, parts of northern Italy and prob-

ably north Africa, were sunk deep in recession.

112

However, the interregional

Mediterranean economy described in this chapter ceased to exist in around

700, and the break was both real and profound. To this limited extent, Henri

Pirenne’s instincts were right. When an integrated, complex Mediterranean

economy (as opposed to a series of incidental exchanges) began slowly to re-

emerge in the Middle Ages, its organisation, its poles of activity and its currents

would be substantially different from those of antiquity.

113

112

Horden and Purcell(2000), pp. 153–72, for a recent assertion of continuing Mediterranean exchange,

but one which in my view goes too far in denying early medieval change. McCormick(2001) takes an

even more optimistic view of the ensuing period, not yet supported by the archaeological evidence.

Forregional variety, Wickham (1998) and (2000a).

113

Iamextremely grateful to Ruth Featherstone, Paul Fouracre, Brigitte Resl, Bryan Ward-Perkins and

Chris Wickham for comments on drafts of this chapter, and to all the members of the ‘Production,

Distribution and Demand’ working group of the ESF-funded Transformation of the Roman World

project, from whom I learnt a great deal.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

chapter 23

THE NORTHERN SEAS (FIFTH TO

EIGHTH CENTURIES)

St

´

ephane Lebecq

It is a well-known fact these days that the seas of northern Europe – from the

Atlantic to the Baltic, by way of the Channel and the North Sea – are amongst

the busiest and most used in the world. But at what point did they begin to play

a significant role in Europe’s system of communications and trade? Despite the

numerous claims handed down to us by Pytheas, Caesar, Strabo, Pliny, Tacitus,

Ptolemy and others in their travel memoirs or in their geographies, it is clear

that, in ancient times, northern Europe was a distant horizon. It was almost

the furthermost, just like certain of its inhabitants, such as the Morins of the

Pas-de-Calais, whom Virgil described as extremi hominum.

1

At that time, the

Mediterranean was the chief axis for trade and exchanges, not only between

East and West, but also between South and North. The Northern Seas were

then simply a distant destination in a communications system in which – to

take a single example – traffic between Roman Britain and the continent was

justified chiefly by the military requirements of the Empire and by its need for

supplies of metal. It is clear from studying written sources and archaeological

and numismatic artefacts that it was during the early Middle Ages that the

Northern Seas started to play an essential role in the communications system

and economy of the Western world.

Henri Pirenne, the founding father of the economic history of medieval

Europe, was the first to declare that it was in the eighth century that the

Western world’s political and economic centre of gravity moved away from

the South towards the North. This was when Islam’s lightning conquest had

succeeded in tying up a large section of the Mediterranean coasts and coastal

lands. It was then that the Northern Seas began to play an active role in the

European system of communications – even if only at a modest level until

the beginning of the eleventh century.

2

The most recent research, in which

archaeology and numismatics have, to some extent, begun to fill in the gaps in

1

Aeneid viii.727.

2

Pirenne (1939), passim.

639

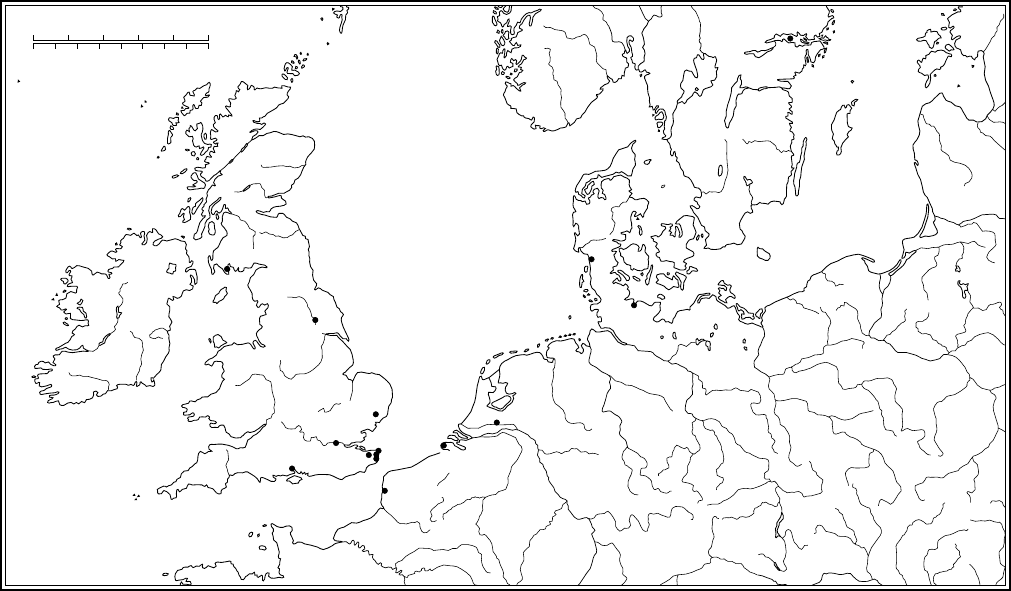

0

0

50

250 miles

100

400 km

100 150 200

200 300

Whithorn

Eorforwich

(York)

Hamwih

Lundenwich

(London)

Ipswich

Fordwich

Dorestad

Walcheren/

Domburg

Quentovic

Sarre

Canterbury

S

a

n

d

w

i

c

h

Ribe

Sliaswich/

Haithabu

Helgo/Birka

Bornholm

NORTH

SEA

E

n

g

l

i

s

h

C

h

a

n

n

e

l

T

h

a

m

e

s

W

e

s

e

r

E

l

b

e

R

h

i

n

e

B

A

L

T

I

C

S

E

A

IRISH

SEA

Map 18

North Sea emporia

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Northern Seas (fifth to eighth centuries) 641

the rather fragmentary written evidence, has largely confirmed Henri Pirenne’s

overall chronology, but has challenged his explanations.

3

In fact, it appears, first,

that it was between the end of the sixth century (when the major Celtic and

Germanic migrations in the Northern Seas basin came to an end) and the course

of the ninth century (when increasing Viking piracy began to disrupt Western

communications) that a real maritime economy developed in northern Europe

for the very first time. Secondly, this phenomenon cannot be explained as a

result of the transformation of the Mediterranean world. Thirdly, it can be

explained by reasons peculiar to the coastal lands of the Northern Seas, and in

particular to changes in their ethnic, political and social environment and to

their own economic development. But before discussing the emergence of this

new maritime economy, it is appropriate to recall just what was happening in

the Northern Seas at the end of the sixth century.

the legacy of late antiquity

Since the end of the third century, communications in the northern seaways,

especially between the British Isles and the continent, had been interrupted

by maritime migrations and concomitant piracy. This was to be rampant for

two or three centuries, even though an important part of these movements had

been undertaken and controlled by the Roman Empire itself for the purpose of

its coastal defence.

4

However, the movements of Celtic peoples in the western

seas (from Ireland to western Britain; from Scotland to southern Britain; from

south-western Britain to Brittany) began to slow down during the second half

of the sixth century.

5

And in the East, after two centuries of a so-called ‘Saxon’

migration and piracy (where, in fact, Saxons were accompanied, or followed, by

Jutes from northern Denmark, Angles from Schleswig-Holstein, Frisians from

the Netherlands, and even Franks from the Rhine and Meuse delta area),

6

the

raid of Danus rex Chlochilaichus (probably the Hygelac of the poem Beowulf )

around 525 to the northern shores of Gaul was the last maritime movement of

aGermanic people to be explicitly recorded in written sources.

7

Of course, insecurity made peaceful communications along the northern

and western seaways more difficult, but not necessarily impossible, and some

ancient shipping routes remained busy. For instance, we know that, during the

period 450–650, there was a relatively important connection from the eastern

Mediterranean to far north-western Europe, which passed along the Spanish

and Gaulish coasts. The Life of John the Almsgiver (a patriarch of Alexandria,

who died in 619) tells us of a merchant ship which sailed from Alexandria to

3

Hodges and Whitehouse (1983).

4

Higham (1992); Jones (1996); James (2001).

5

Thomas (1986); McGrail (1990).

6

Myres (1989); Jones (1996).

7

Gregory, Hist. iii.3.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

642 st

´

ephane lebecq

‘the Isles of Britain’ (i.e. probably the islands known during antiquity as the

Cassiterides – the Isles of Scilly and the south-western British mainland) in

twenty days and nights with a cargo of corn, and returned with a cargo of

gold and tin.

8

So long after the collapse of the Roman Empire and the end

of the pax Romana, the reader might easily dismiss this account as a fable.

However, the discovery of a significant quantity of fifth- and sixth-century

jars, bowls and amphorae (the so-called ‘A’ and ‘B’ wares of the archaeologists)

from the eastern, central and western Mediterranean in several aristocratic

and/or princely sites in Ireland (Garranes and Clogher) and the British far

west (Tintagel in Cornwall, Dinas Powys in Wales) and north (Dumbarton

Rock) proves that such connections lasted during the Dark Ages.

9

But such a well-documented (in a manner of speaking) example is rare,

because usually the written sources are very sketchy. Except for a few rare,

late and sometimes doubtful allusions in some Irish saints’ Lives to the rela-

tions between Atlantic Gaul and the distant Celtic countries of north-western

Europe,

10

the sources of the sixth century tell us nothing about any commercial

traffic between the continent and the British Isles. The most important Roman

ports (like Gesoriacum-Bononia (Boulogne) on the continent, or like Dubris

(Dover) or Rutupiae (Richborough) in Britain) are no longer mentioned. These

were military ports connected, during a first period (the first to third centuries),

with the Classis Britannica, the fleet which controlled imperial relations with

the province of Brittania, and, later (the fourth to fifth centuries), with the

defensive coastal system of the Litus saxonicum.

11

And if the names of ancient

cities like Rotomagus (Rouen), Namnetas (Nantes), Londinium (London) or

Eboracum (York) still appear in sources, they are no longer referred to as ports.

Of course, this does not mean that all types of relations ceased to exist

between the Isles and the continent – far from it, because the migrations

resulted in the settlement of actively maritime peoples in all the coastal areas of

north-western Europe. Henceforth (say from the middle of the sixth century),

there was an almost continuous Celtic settlement along the western seaways.

There were more and more Scotti (Irish) from Hibernia (Ireland) in Caledonia

(Scotland) – particularly in D

´

al Riada (the south-west of Scotland) – and

in Cambria (Wales) – especially in Dyfed;

12

more and more Brittones from

Cambria and Dumnonia (Cornwall and the south-western peninsula) were to

be found in ancient Armorica, which began to be called Brittania (Brittany) in

the second half of the sixth century.

13

As for the maritime Germans, they settled

not only in the east and south of Britain where, in spite of recent arguments to

8

Leontius of Naples, Life of John the Almsgiver, ed. Festugi

`

ere, pp. 353–4 and 452–3.

9

Thomas (1988) and (1993), pp. 93–6;Fulford (1989).

10

James (1982), pp. 375–8;Johanek (1985), pp. 227–8.

11

Johnson (1976) and (1977).

12

Thomas (1986).

13

Fleuriot (1980); Cassard (1998), pp. 15–57.