Fouracre P. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 1: c. 500-c. 700

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Kings and kingship 603

the Old Testament offered the best ideological underpinning for an integra-

tion of Christian principles with martial priorities. Their kings were the first

to be anointed when inaugurated, perhaps already in 631, certainly by 672.

185

Especially notable was the Church’s liturgical commitment to Visigothic royal

victory. Carl Erdmann found Spain ‘out of line’ with the rest of Europe in its

precocious development of the crusading ideal.

186

As at Byzantium, a biblical model had more attractive facets. It was pre-

sumably its harping on the duty to provide for the down-trodden that induced

King Oswald to break up the silver dish from which he had been consuming

his Easter banquet to supply largesse for beggars. Frankish contemporaries of

Justinian built xenodochia.

187

St Denis was already the ‘special patron’ of the

Merovingian dynasty, and kings were mainly buried in his abbey. But Clovis II

was said to have scandalised his monks by stripping silver from the apse of the

church so as to benefit the poor.

188

A paradox of late Roman rule thus recurred

in the sub-Roman West: kings whose power increasingly distanced them from

the run of their people (not that they were so far removed as in Constantinople’s

palace) were brought closer in principle to their least privileged subjects.

conclusion: dolittle kingship

In the winter of 749–750, the pope was visited by the abbot of St Denis and an

English bishop from the Bonifatian circle. They had been sent by an uniden-

tified but hardly mysterious authority to ask whether it was a good thing

that Frankish kings should not have ‘kingly power’? One of history’s most

famous leading questions duly produced the right answer: ‘Pope Zacharias

instructed Pippin that it was better to call him king that had power than

him who remained without royal power.’ Pippin was accordingly ‘elected

king according to Frankish custom, anointed by the hand of Archbishop

Boniface . . . and elevated by the Franks to the kingdom . . . while Childeric,

who was falsely called king, was tonsured and sent to a monastery’.

189

Zacharias’ answer has ever since seemed the only one possible. But this was

because it led to the masterful rule of the Carolingians, and still more per-

tinently to Einhard’s Life of Charlemagne, where the last Merovingians were

unforgettably reduced to laughing-stocks. The circumstances have ensured

that the pre-750 period’s best-remembered legacy was not the formidable force

185

King (1972), pp. 48–9 (n. 5).

186

Erdmann (1935/1977), pp. 6, 22, 30, 39, 43, 82 (which made it a backwater to his Francocentric

view); contrast the powerful discussion by McCormick (1986), pp. 304–12.

187

Bede, HE iii.6:Wood (1994), p. 184.

188

Wood(1994), p. 157: for ‘peculiaris patronus noster’ and the more normal Merovingian reciprocation

of his favours, see Diplomata Regum Francorum 48, 51, 61, 64, etc.

189

Annales Regni Francorum, s.a. 749–50,pp.8, 10.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

604 patrick wormald

Germanic kingship had become, but the notion of a ‘shadow-king’, a roi

fain

´

eant, kingship in decline. Yet at least one Frankish aristocrat might not

have agreed with the pope.

190

The author of the Liber Historiae Francorum,

writing in the 720s, gloried in past Frankish triumphs. He was not hostile to

Carolingian military achievement, nor was he contemptuous of the position

the Merovingians by then occupied. So far as he was concerned, at least one

recent king, Childebert III, had done a good job. The job was to ‘do justice’,

which apparently meant to mediate in the feuds of his greater nobles without

excess commitment to any one faction, and to dispense what was left of his

patronage to its most deserving (i.e. already privileged) recipients. There is

not the least hint that kingship in this style was set upon the path to its own

destruction. Further afield, the papal view would not have been the one taken

by the Liber author’s Old Saxon contemporaries. The fierce resistance they put

up to Charlemagne’s campaign of Christian conquest is partly explained by

attachment to a system where rulers took ‘kingly power’ temporarily and by

casting lots.

191

Even Bede, another contemporary, who deplored the dissipa-

tion of his native Northumbria’s royal resources as forcefully as any Einhard,

had learned from Augustine and (it may be) from the Irish that the summum

bonum was not the rule in this world. He could not withhold his admiration

for strong kings like Ine who forsook all to seek St Peter’s threshold.

192

In 700,

European kingship was still hedged about with the ambiguities bequeathed by

its Hebrew and Roman models, and perhaps by abiding barbarian traditions,

both Celtic and Germanic.

Butitwas the sort of answer to be expected of a Greek-speaking inhabi-

tant of Byzantine Calabria like Zacharias, and one whose office embodied the

‘Ghost of the old Roman Empire, sitting crowned upon the ruins thereof’ (in

Hobbes’ classic phrase). It was the answer expected not only by the Frankish

nobles whose support the Carolingians had assiduously cultivated but also by

Boniface, a regular correspondent of Zacharias, who went on to play Samuel

to Pippin’s Saul. He had recently welcomed the kingly power of his fellow-

Englishman, Æthelbald of Mercia, while earnestly threatening him (the fate of

Islam’s Spanish victims on his mind) with what would come of failing to exer-

cise it in accordance with God’s law.

193

The western European future did now

lie with kings who, like basileis in Constantinople and khalifah in Baghdad,

were God’s agents on earth.

190

For what follows, see Gerberding (1987).

191

Cf. Mayr-Harting (1996).

192

Bede, Epistola ad Ecgbertum Episcopum 10–13,pp.413–17; HE v.7.19.Cf. Stancliffe (1983); Thacker

(1983).

193

Bonifatii Epistolae,no.73.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

chapter 22

THE MEDITERRANEAN ECONOMY

S. T. Loseby

contexts: evidence and antecedents

Tw o issues that shape any general interpretation of the Mediterranean economy

of the sixth and seventh centuries are the problems of the available evidence

and the question of the nature of the ancient economy that preceded it. The

limitations of the written sources are well known. In particular, no documen-

tary data survive of a type that permits any serious attempt at quantitative

analysis. Instead of the records which are the stuff of economic history, we

usually have only stories. There are a handful of short texts that are wholly

or partly concerned with economic matters. For the most part, however, we

depend upon anecdotal indications afforded by a host of authors united by

little more than their indifference to economic affairs, in whose writings the

fleeting appearances of merchants or traded goods are almost invariably tan-

gential. Gregory of Tours, for example, reports how a ship from Spain put in

at Marseilles in 588, carrying the ‘usual cargo’. He tells us this to provide the

context for an outbreak of the plague, disseminated through the port via the

purchase of this merchandise, but in the absence of any other direct references

to Mediterranean exchange between Spain and Francia in this period, its nature

remains a matter for speculation.

1

Even Leontius of Naples’ Life of St John the

Almsgiver, which offers an exceptional series of insights into the commercial

relationships of the church of Alexandria in the early seventh century, does so

less from any sense of their intrinsic importance than because of their value as

illustrations of the charitable behaviour of its main protagonist.

2

The economic history of this period has necessarily been constructed

through the prising of such jewels of information from their various settings,

but also their intricate rearrangement in the service of more ornate general argu-

ments. The classic and most ambitious example is the thesis of Henri Pirenne,

1

Gregory, Hist. ix.22.

2

Leontius, Life of St John the Almsgiver.

605

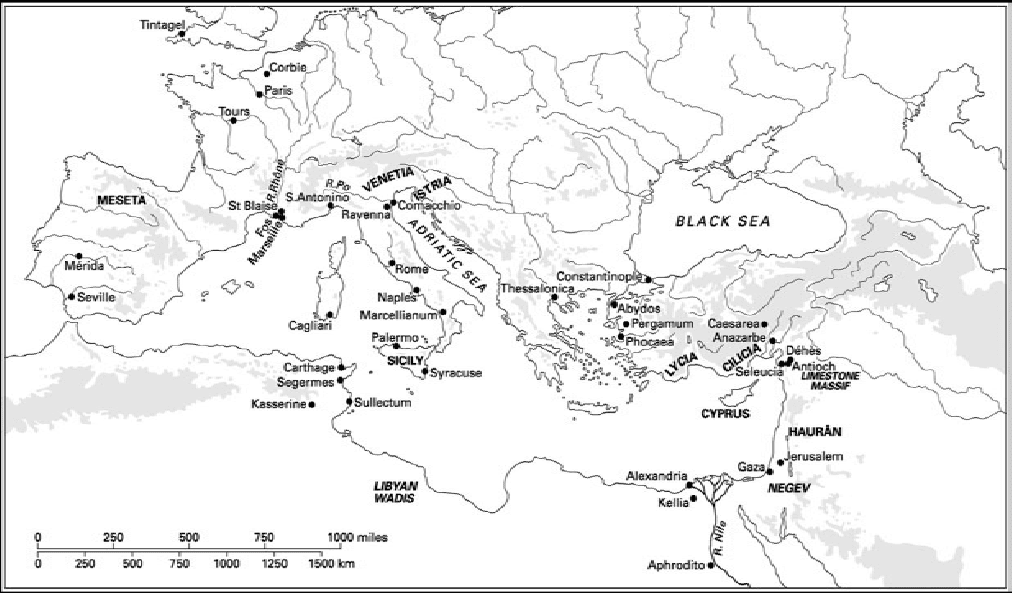

Map 15

The Mediterranean economy: sites and regions mentioned in the text

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Mediterranean economy 607

whose shadow has loomed large over the subject ever since the posthumous

publication of his provocative work Mahomet et Charlemagne. There he argued

that the ancient economy survived the barbarian invasions of the fifth cen-

tury unscathed, but was destroyed by the rise of Islam in the seventh, which

ruptured the unity of the Mediterranean. This established the framework of

the historiographical debate about the post-Roman Mediterranean economy

for decades, even as his numerous critics demonstrated the fragility of many

of Pirenne’s assertions.

3

A less impressionistic approach has been to organise

the fragmented data thematically in the hope of identifying general patterns, a

method which reached its apogee in the compendium of references to western

Mediterranean trade in the early Middle Ages assembled by Dietrich Claude;

this has the twofold merit of being both more comprehensive, and more cau-

tious in its conclusions, than many of its predecessors.

4

Works such as this

provide an invaluable (and virtually fixed) canon of the available evidence, but

cannot alter the fact that its deficiencies remain considerable, and in some

cases frankly insurmountable. In part this is a function of familiar imbalances

in the early medieval documentary tradition; we have far more data from some

regions than from others. More generally, the limited quantity and relent-

lessly anecdotal nature of the evidence that does survive makes it decidedly

hazardous to elucidate general economic circumstances from the specifics of

any given story. Our knowledge of the whys and wherefores of early medieval

exchange is a composite, pieced together from assorted snippets of informa-

tion, which are neither necessarily typical nor readily comparable, and virtually

never comprehensive.

To take just one example, a Jewish merchant named Jacob set off from Con-

stantinople in around 632 on a commission from a distinguished inhabitant of

the city to sell illicitly textiles worth two pounds of gold, receiving an annual

retainer of around 10 per cent of the value of the goods for his pains.

5

Jacob had

considered the possibility of finding buyers in Africa or Gaul, but eventually

managed to dispose of all his stock on the quiet to customers in Carthage.

Shorn of the many complications involving Jacob’s conversion from Judaism

to Christianity (the latter being the main point of this probably fictional nar-

rative), the commercial mise en sc

`

ene seems highly plausible, but many of its

details remain exceptional or enigmatic.

6

It is, for example, the only recorded

instance from our period of a Mediterranean merchant working on commis-

sion for a member of the secular elite, and the only explicit statement of a

3

Pirenne (1939). The critiques and sequels Pirenne inspired are too many to list, but see especially

Riising (1952), and Hodges and Whitehouse (1983).

4

Claude (1985).

5

Doctrina Jacobi v.20, with the commentary in Dagron and D

´

eroche (1991).

6

Other data on the activities of merchants in this period are collected in Claude (1985), pp. 167–244.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

608 s. t. loseby

conscious awareness of alternative markets. It is left unstated whether Jacob

was acting solely on behalf of his patron, whether he was paid in cash or kind,

and whether he might also have intended to exploit the possibilities of the

voyage on his own account, for example by bringing back a cargo for sale

in Constantinople. Fascinating though Jacob’s story is, without comparable

information its value as evidence of normal commercial practice is extremely

difficult to assess. The necessity of accumulating such anecdotes from different

times and places, with their diverse emphases and omissions, encourages the

plugging of the gaps in one singular story with equally unique details from

another. The written sources enable us to see what was possible; the idea of

Jacob undertaking such a voyage early in the 630sisinitself intriguing. But

the information they provide is too meagre to show what was typical.

The somewhat sterile debate about the nature of the early medieval Mediter-

ranean economy, long structured around an inadequate corpus of documentary

evidence and a conceptual framework bequeathed by Pirenne, has since the

1970s been reinvigorated by continuous transfusions of new archaeological

data. Changing patterns of urban and rural settlement offer numerous insights

into economic relationships, whether through case-studies of particular sites,

or by the exploration of more extensive areas via field-survey and even, in

privileged areas such as the limestone massif of northern Syria, examination of

standing structures.

7

The analysis of archaeological finds yields more explicit

information concerning the production and distribution of certain manufac-

tured goods. In particular, the recovery of thousands upon thousands of sherds

of pottery (useless to its owners once broken, but invaluable to archaeolo-

gists because it is virtually indestructible in the ground) allows the detailed

study both of pottery as a traded commodity in its own right, and also of the

exchange of those foodstuffs which in antiquity were routinely transported

in ceramic amphorae, including such Mediterranean dietary staples as olive

oil, wine and fish-sauce. Much painstaking research now makes it possible to

assign a lot of this ceramic material to a specific region of production, and

to classify and date the most common and widely exchanged ceramic types

with ever-increasing precision.

8

Ceramic assemblages can then be analysed in

various ways, for example to show the patterns of consumption implicit in the

range of amphorae recovered from a given site (Map 16), or the distribution

of a certain form of pottery (Maps 17a and 17b). All this offers the mass of

serial data and the possibilities for statistical analysis conspicuous only by their

absence from the written record. Ceramic distributions can be used to reveal

7

Foranoverview, Ward-Perkins (2000a).

8

Among a vast literature one should single out the pioneering work of John Hayes (1972) and (1980)

on African Red Slip ware, and the widely used classifications of the most common amphora types

established by Riley (1979) and Keay (1984).

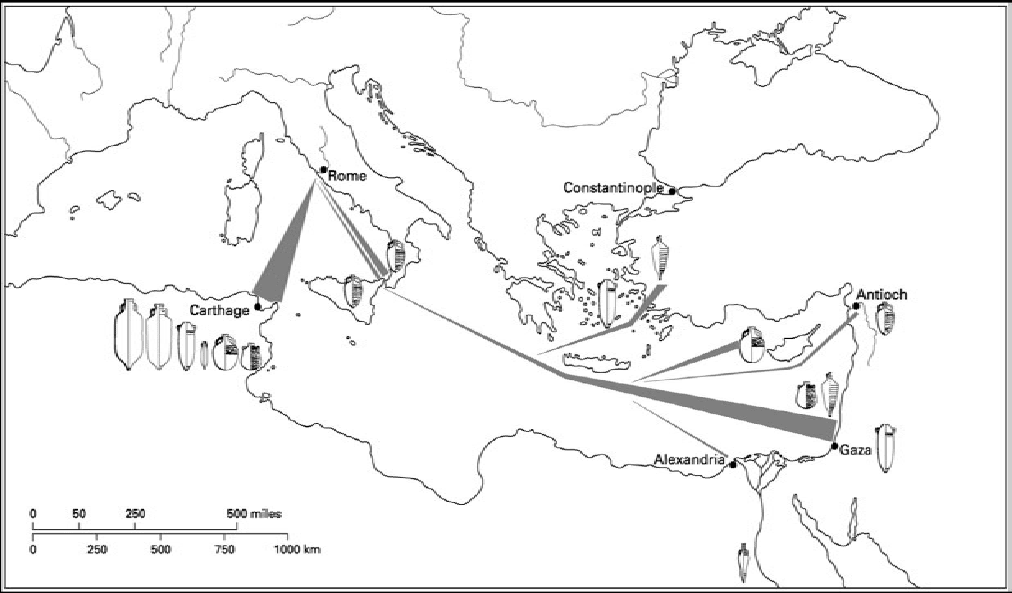

Map 16

Imported amphorae (see Figure

8)inalate seventh-century deposit at the Crypta Balbi, Rome;

the arrows represent import volumes calculated on the basis of amphorae

capacities (after Panella and Sagu

`

ı(2000), fig.

4)

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

610 s. t. loseby

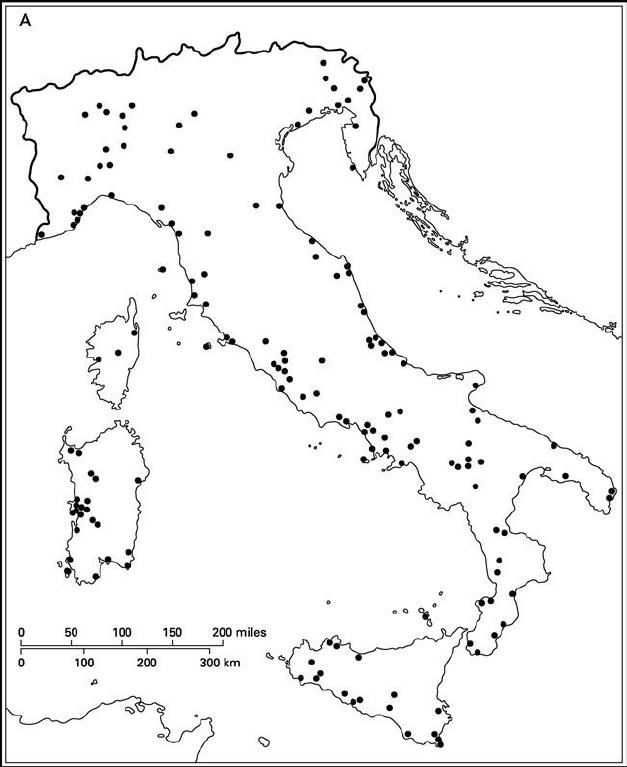

Map 17AFindspots of African Red Slip ware in Italy: c.450–570/580

(after Tortorella (1998), fig. 7)

not merely the existence of exchange networks, but also their evolution over

time.

The problem remains that the archaeological evidence is as restricted in

scope, and potentially as open to interpretation, as the written sources. Many

of the items of early medieval exchange most commonly mentioned in the

texts, from spices to slaves, are not archaeologically retrievable. Nor do the

types of container that circulated alongside amphorae, such as barrels, sacks

and skins, normally survive in the ground. Closer analysis of the production

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Mediterranean economy 611

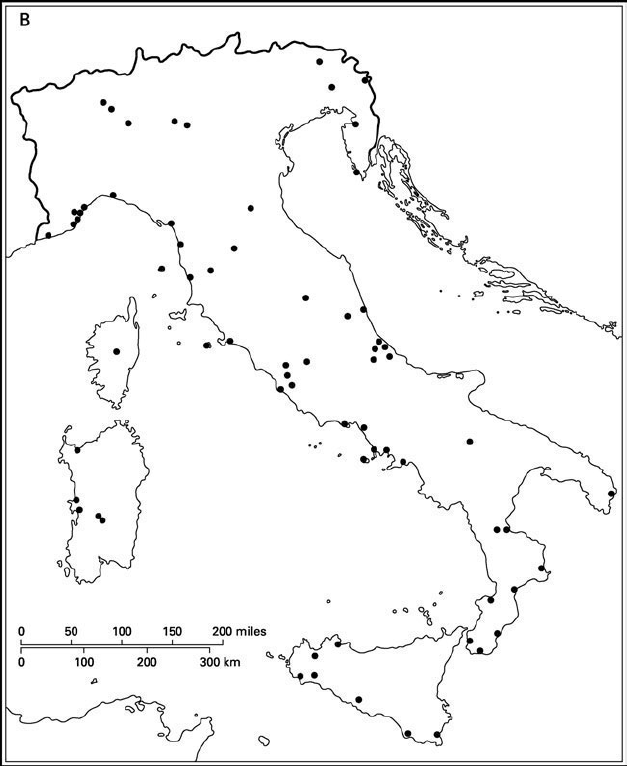

Map 17BFindspots of Red Slip ware in Italy: c.550–seventh century (after Tortorella

(1998), fig. 8)

and distribution of other materials which can be recovered, such as glass, or

building-stone, may in time prove possible, but our archaeological percep-

tion of the post-Roman Mediterranean economy will remain overwhelmingly

dominated by the ceramic evidence.

9

This is far from ideal, but the impres-

sion it gives is nevertheless likely to be broadly representative of the wider

9

Such analysis is currently only possible for the production and distribution of one easily distinguish-

able, but particularly valuable and so atypical building-stone, marble: see e.g. Sodini (1989).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

612 s. t. loseby

economic picture.

10

Pottery is an everyday commodity that was manufactured

throughout the late antique world to a range of specifications extending from

standardised fine wares disseminated in vast quantities from North Africa to

basic hand-shaped vessels produced within the household for domestic use.

Patterns of ceramic production and distribution can therefore shed light upon

all tiers of the economy from the international to the local. The relative sophis-

tication of the pottery industry is probably also a reliable index of the general

complexity of the contemporary economy. In periods where high-quality pot-

tery could be mass-produced and widely distributed, it seems reasonable to

assume that other industries specialising in everyday items, such as textiles or

timber, were capable of operating on a similar level. A reliance upon basic

local manufactures, on the other hand, would suggest an absence either of

demand, or of the transport and marketing structures required for regional

pottery distribution, and so imply simpler economic systems. The widespread

use of amphorae as containers in our period, together with the tendency to

ship pottery as a convenient space-filler alongside other more valuable cargoes,

also means that ceramic distributions are likely to be indicative of general pat-

terns of exchange, not merely of networks peculiar to the pottery industry.

11

Ourarchaeological perception of early medieval Mediterranean production for

export is irrevocably biased in favour of those regions which produced widely

distributed ceramics, such as African fine-ware pottery or Syrian amphorae.

Even so, this distortion is unlikely to be entirely misleading because it was the

very significance of these regions within the interregional tier of the economy

that enabled them to sustain the production and distribution of wine, oil and

pottery on an industrial scale.

A more serious difficulty is that, as desirable as findspot distribution maps

and accumulations of statistical evidence are, they can never in themselves

reveal how the early medieval Mediterranean economy worked. The written

sources at least tell us stories; archaeologists have to supply their own. Despite

remarkable advances in recent years in the identification and dating of par-

ticular types of pottery, it remains a matter of interpretation precisely how,

why and for whose benefit such items were transported around the Mediter-

ranean. Excavations have shown, for example, that the inhabitants of St Blaise,

aProvenc¸al hillfort reoccupied in late antiquity, were able to acquire imports

from distant regions of the Mediterranean until at least the late sixth century.

12

They drank Gaza wine, one of the grands crus of the day, shipped in distinctive

elongated chestnut-coloured amphorae known to specialists as Late Roman

Amphora (LRA) type 4 (Map 16 and Fig. 8). They ate from fine bowls and

10

Peacock (1982).

11

Peacock and Williams (1986).

12

D

´

emians d’Archimbaud et al.(1994).