Fouracre P. The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 1: c. 500-c. 700

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Mediterranean economy 613

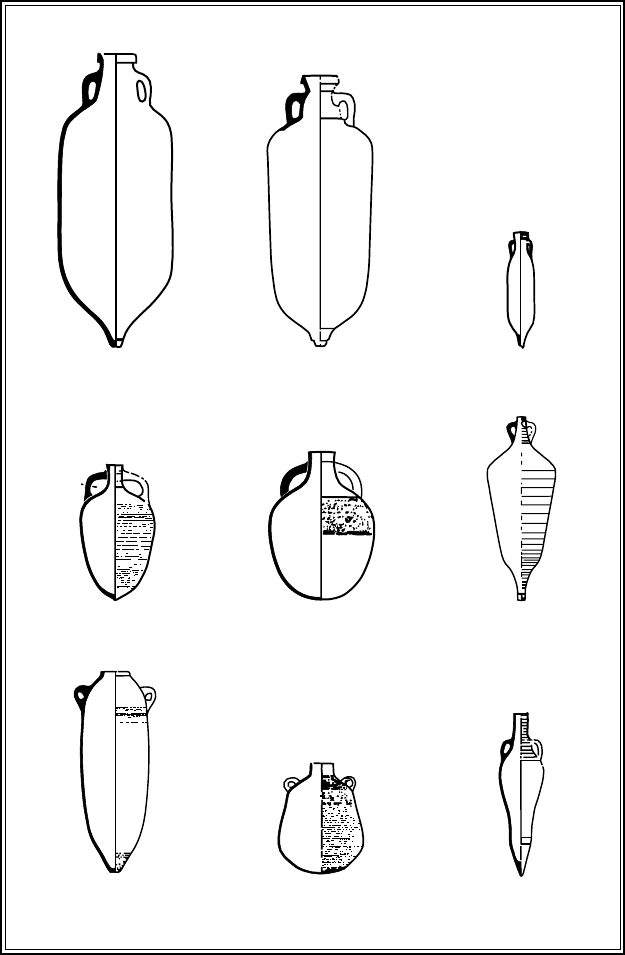

KEAY LXI KEAY LXII KEAY XXVI

LRA 1 LRA 2 LRA 3

LRA 4 LRA 5/6 LRA 7

Figure 8.Some of the principal classifications of African and eastern Mediterranean

amphorae in interregional circulation in the sixth and seventh centuries (African:

Keay xxvi (spatheion); Keay lxi;Keay lxii. Eastern Mediterranean: LRA 1–7)

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

614 s. t. loseby

dishes manufacturedin workshops in what is now Tunisia; this is the ubiquitous

African Red Slip ware (ARS), the dominant international pottery of the period,

and the most closely studied of all late antique ceramic types. But although

we can classify and date some of the material found on sites like St Blaise with

increasing precision, this does not help us to understand how it got there. It

seems reasonable to assume that its presence involves trade, but the nature and

number of the exchanges requiredto transport wine from producers in Palestine

to eventual consumers on a Provenc¸al hilltop is a matter of speculation. A

distinction between ceramics of ‘African’ and ‘eastern Mediterranean’ origin is

conventionally drawn in discussions of archaeological deposits of this period,

and it will be used faute de mieux as a heuristic device in what follows. But

the relative proportions of such material at any given site cannot confidently

be used as a reflection of the scale of direct exchange between producing and

consuming regions; much eastern material may, for example, have found its

way onto western markets via intermediate ports such as Carthage. The few

Mediterranean shipwrecks of this period to have been recovered also generally

carry heterogeneous cargoes, emphasising the diversity and complexity of the

exchanges underlying the ultimate distribution of finds.

13

These and other

similar problems ensure that the information provided by a ceramic assemblage

such as the one recovered from St Blaise is, like the story of Jacob the merchant,

evocative but incomplete. The archaeological material does, nevertheless, have

some advantages. Since it offers a picture of diachronic change, it is more like a

film than a snapshot. And although excavated finds can say little in themselves

about the social and economic bases of their production and distribution, they

can be much more readily compared with other contemporary assemblages to

reveal outcomes of exchange. At present, every major new excavation around

the Mediterranean which produces substantial stratified deposits from our

period – such as the various UNESCO projects in Carthage, Sarac¸hane in

Constantinople or the Crypta Balbi in Rome – involves a sharp twist of the

archaeological kaleidoscope, and the rearrangement of its slivers of material

into a slightly different pattern. But while the overall picture remains fluid

and its details sketchy, some broad outlines can be established with increasing

confidence; they can also be usefully compared with the variant perspectives

afforded by the texts.

One consequence of the increased availability of archaeological evidence has

been to transform perceptions of the workings of the ancient economy. Influ-

ential historians had been inclined to take a dim view of trade, emphasising

the primitivism of an economic system where the subsistence sector reigned

supreme over the commercial.

14

Any role for the market economy within

13

Parker (1992).

14

See esp. Jones (1964), pp. 824–58 and (1974); Finley (1985).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Mediterranean economy 615

this minimalist perspective was strictly local. Widespread poverty restricted

demand, while on the supply-side a lack of specialisation, investment and

innovation, prohibitive transport-costs, and the attitudes of an elite who prized

landownership and conspicuous consumption over the maximising of produc-

tion and profit, were all deemed to have conspired to stifle trade. Only the

state, faced with the necessity of supplying its vast personnel and the inflated

populations of its capitals, engaged in the circulation of foodstuffs over long

distances, but as far as possible this was achieved via the annona,inessence a

compulsory purchase and distribution system.

15

Much of the exchange which

did take place within the ancient world and on into our period was therefore

seen not in commercial terms, but as the redistribution of resources by the

state, elites, and latterly other wealthy institutions such as the church, without

recourse to a market economy.

16

This interpretation is text-based, but the archaeological evidence, by reveal-

ing the myriad outcomes of exchange, exposes both the limitations of our

sources and the excessively bleak assumptions of the minimalist viewpoint.

The vast quantities of ARS found on sites all around the Mediterranean in late

antiquity, even in relatively humble rural contexts, are indicative of the large-

scale manufacture of a high-quality product which was sufficiently affordable

to make its overseas distribution viable even where it had to compete with local

fine-ware production. The circulation of commodities such as ARS was almost

certainly influenced by the currents of exchange generated by the state, but it

can hardly have been dictated by them. Similarly, although the state sector was

directly responsible for a significant proportion of interregional traffic in food-

stuffs, the range of amphora manufactures and the fiendish complexity of their

distributions suggests that at least some of this traffic was responding to com-

mercial imperatives. Since the activities of these pottery industries have largely

escaped the notice of the written sources, it follows that the exchange of other

manufactured goods on a substantial scale, such as textiles, is equally possible,

even if it cannot be so readily confirmed archaeologically.

17

Some archaeolo-

gists have explicitly offered more commercially driven interpretations of the

ancient economy; others have been content to do so implicitly by routinely

describing the distributions of excavated material in terms of trade.

18

None of this is to deny, of course, that imperial interests were crucial to

the evolution and nature of interregional exchange within the ancient econ-

omy. Even if the archaeological evidence strongly suggests that the importance

15

Durliat (1990).

16

Whittaker (1983).

17

The surviving documentary evidence from Egypt is the exception: see e.g. Johnson and West (1949),

and Wipszycka (1965) and van Minnen (1986) for textiles.

18

Carandini (1981) and (1986), with the helpful historiographical commentary in Wickham (1988);

Panella (1993), the finest analysis of the archaeological evidence; Reynolds (1995).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

616 s. t. loseby

of the commercial sector has been underestimated, the requirements of the

Roman state did significantly distort the currents of such traffic. The founda-

tion of a new imperial capital at Constantinople in the fourth century had, for

example, generated new flows of exchange that bear some responsibility for

the unprecedented intensity of rural settlement and agricultural production in

several regions of the eastern Mediterranean in late antiquity.

19

In the West,

meanwhile, it has been plausibly argued that a crucial factor which under-

pinned the international distribution of ARS was the dominance of Africa

within the state sector of the economy. More generally, the Roman state had

indirectly stimulated commercial exchange in various ways. The taxes, which it

demanded from the peasantry, required them to commoditise their surplus to

turn it into coin. Those coins, minted primarily for fiscal purposes, offered an

empire-wide medium of exchange in the form of a single currency. The infra-

structural and financial underpinning of the annona system may have been in

the public interest, but, as we shall see, it also greased the wheels of the private

enterprise carried on alongside it.

20

In the eastern basin of the Mediterranean, the intertwining of the state and

commercial sectors of the economy created complex networks of interregional

exchange, which would persist for much of our period, until they were even-

tually dislocated by the near-collapse of the Byzantine Empire.

21

In the West,

however, the disintegration of the imperial fiscal and military machine in the

fifth century perpetuated an existing pattern of decline which the reincorpo-

ration of some regions of the western Mediterranean – notably Africa – into

the eastern system as a result of Justinian’s reconquests would do little to arrest.

Here the sixth and seventh centuries are marked not by any radical break with

the past, but by the relentless contraction of the economic networks inherited

from antiquity. On the one hand, this supports the view that the commercial

sector of the Mediterranean economy had always been important, and, as such,

could continue with or without an empire; the hegemony of African ceramics

on overseas markets, for example, survived both the supposed disruption of

the Vandal conquest and the restoration of imperial authority from the east.

22

On the other hand, it is striking that no wholly new networks of interregional

exchange emerge from the wreckage of the Western Empire. As a result, the

grand narrative of the sixth- and seventh-century Mediterranean economy, in

so far as such a thing exists, is about the impact which the disintegration of

19

Abadie-Reynal (1989).

20

Hopkins (1980) and (1983); Mattingly (1988); Wickham (1988); McCormick (1998).

21

Kingsley and Decker (2001).

22

Panella (1993), esp. pp. 641–54.Various efforts have been made to interpret the ceramic evidence

in the specific light of these political changes (e.g. Fulford (1980) and (1983)), but these are not

compelling (Tortorella 1986).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Mediterranean economy 617

the military, political and (not least) cultural authority of the Roman Empire,

gradual in the West and more dramatic in the East, had upon the contin-

ued functioning of the ancient exchange-system. But the Mediterranean is a

complex of seas, and as such has always nurtured a complex of economies.

23

So before embarking upon that grand narrative, some attention must first be

paid to the local and regional orbits of exchange which lurk beneath the sur-

face of the pan-Mediterranean economy, and to the commodities which were

circulating within these subsidiary systems.

contents: orbits and objects

Oneofthe defining characteristics of pre-industrial economics is the consider-

able differential in the respective costs of land- and water-transport. Although

precise information from the Roman period is in short supply, it is compati-

ble with the better data which survive from later centuries in suggesting that

transport overland was about five times more expensive than by river, and

well over twenty times more expensive than by sea. Jones put this briskly

into perspective by using the authorised carriage-tariffs in Diocletian’s price

edict to show how it was cheaper to ship grain from Syria to Spain than to

cart it just 120 kilometres.

24

In normal circumstances it made no commercial

sense to transport overland low-value or bulk items such as grain; the state

would do so to secure essential supplies, but here the inflated expense was not

the main concern. Moreover, transport by sea was much quicker, given a fair

wind, although the Mediterranean was considered too hazardous for sailing

for almost half the year, and the dangers involved are frequently highlighted

by the written sources.

25

During the patriarchate of John the Almsgiver, for

example, at least thirteen vessels belonging to the church of Alexandria were

hit by a storm in the Adriatic and forced to jettison their entire cargoes; the

Alexandrine sea-captains who were in the habit of sprinkling their ships with

holy water from the River Jordan before setting out were taking a reasonable

precaution.

26

The risks, however, were well worthwhile, since the Mediter-

ranean opened up commercial possibilities for coastal centres, or those with

access to a navigable waterway, which were denied to communities inland. In

recounting the problems in times of famine of a landlocked city like Caesarea

in Cappadocia, set amid the mountains some 200 kilometres from the coast,

Gregory of Nazianzus offered a succinct summary of the structural constraints

23

Braudel (1972), p. 17.

24

Jones (1964), pp. 841–2;cf. Durliat (1998), pp. 92–3.For a not altogether convincing attempt to play

down this differential, see Horden and Purcell (2000), p. 377.

25

Claude (1985), pp. 31–2.

26

Leontius, Life of St John the Almsgiver c.28; Antonini Placentini Itinerarium 11.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

618 s. t. loseby

which continued to apply throughout our period: ‘coastal cities support such

shortages without difficulty, as they can dispose of their own products and

receive supplies by sea; but for us inland our surpluses are unprofitable and

our scarcities irresolvable, because we have no means of disposing of what we

have nor of importing what we lack’.

27

The relative ease of water-transport was

not only vital in a crisis; potentially, it also afforded regular access to a wider

market for the disposal of surplus production.

This ready maritime ‘connectivity’ was the essential precondition for the

existence of a Mediterranean economy.

28

In practice, however, the similar eco-

logical resources of its shores, where differences tend to exist within rather

than between regions, might have been expected to reduce the commercial

possibilities. Most importantly, all of them are capable of sustaining the pro-

duction of the trinity of sixth-century Mediterranean staples: grain, oil and

wine.

29

The interregional shipment of foodstuffs was not generally necessary

for subsistence purposes, except to supply the imperial capitals. When poor

harvests and crop failures inevitably did occur, neither the bad news nor the

necessary relief could usually arrive fast enough to permit the opportunistic

exploitation of short-term crises by distant producers and suppliers.

30

In nor-

mal circumstances, meanwhile, goods transported hundreds of kilometres by

ship could perhaps compete in price with equivalent items conveyed relatively

short distances overland, but scarcely with the local grape harvest or pressing

of olive oil. John the Almsgiver admired the heady bouquet of the expensive

Palestinian wine he was offered in the church of St Menas in Alexandria, but,

with characteristic abstemiousness, he spurned it in favour of the local vintage

from Lake Mareotis; its taste was nothing special, but the price was low.

31

In the sixth and seventh centuries, as throughout the Roman and medieval

periods, transport costs combined with the relative poverty of the population

to ensure that the most significant tier of the exchange-network for producers

and consumers alike was the local one. The vast majority of people were directly

engaged in labour-intensive agricultural production. Their primary aim was to

grow enough food for their dependants and themselves to survive the year (and

the risk of starvation was real), whilst meeting the demands for tax or rent from

the state and from landlords; when these demands were expressed in cash rather

27

Gregory of Nazianzus, Orations xliii.34.

28

‘Connectivity’: Horden and Purcell (2000), ch. 5.

29

Cassiodorus, Variae xii.22.1 for wine, grain and oil as the three ‘excellent fruits’ of agriculture.

Justinian, Institutiones iv.6.33 cites the same trilogy of goods as selling at different prices in different

places.

30

Cassiodorus, Variae iv.5, with Ruggini (1961), pp. 262–76, and Miracula Sancti Demetrii i.9.76, for

King Theoderic’s and St Demetrius’ exceptional attempts to use their respective powers to get round

this problem.

31

Anon., Life of John the Almsgiver, c.10.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Mediterranean economy 619

than in kind, their participation in the market economy was essential to convert

their produce into coin. If they managed to produce a surplus after this, they are

most likely to have exchanged it locally for other foodstuffs or manufactured

goods. This level of exchange usually takes place beneath the notice of the

written sources, although the occasional anecdote confirms its existence. After

invading Vandal Africa, for example, the Byzantines gained entry to Sullectum

by the simple expedient of attaching themselves to the peasants entering the city

at first light with their carts, clearly an everyday occurrence.

32

A fragmentary

inscription from Cagliari in Sardinia sets out the customs dues levied in kind by

the civic administration in the reign of Maurice (582–602)ongoods entering

the territory of the city on pack-animals, small boats or, easiest of all, on the

hoof. In describing the convergence of a range of basic commodities upon a

local market by land and sea, it offers an unusual glimpse of what must have

been the normal relationship between peasant producers and neighbouring

communities.

33

In return, of course, these communities afforded access to

expertise as well as agricultural produce. In the time of Justinian, the vibrant

Egyptian village of Aphrodito supported at least sixty shopkeepers, artisans and

professional men divided between nineteen specified occupations, including

a potter of some substance.

34

Exchange at this local level is now becoming

more perceptible through patterns of pottery production and distribution.

Even so, the study of the common wares of this period is in its infancy, and

the unchanging nature and household manufacture of many of these items

means that progress is slow. Although archaeology can also tell us a great deal

about the provisioning of specific sites through, for example, analysis of pollen

grains and, perhaps most promisingly, animal bones, at present it remains

easier to assert the fundamental importance of exchange at the local level –

and of myriad micro-economies within the Mediterranean economy – than

it is to subject the operation of these networks to meaningful comparative

analysis.

35

The same is no longer true of the regional networks, which make up the

intermediate tier of Mediterranean exchange. The ever-expanding number of

sixth- and seventh-century pottery assemblages and the growing sophistica-

tion with which these can be analysed make these systems increasingly dis-

tinguishable as specific entities. Many regions of the Mediterranean sustained

32

Procopius, Wars iii.16.10.

33

Durliat (1982). Cf. the fifth/sixth-century customs tariff from Anazarbe in Cilicia: Dagron and Feissel

(1987), pp. 170–85 (no. 108).

34

Catalogue g

´

en

´

eral d’antiquit

´

es

´

egyptiennes, ed. Maspero, iii.67283, 67288;Jones (1964), pp. 847–8;

Keenan (1984). The exceptional survival of data from Aphrodito should not blind us to the fact that,

as a demoted metropolis beside the Nile, it was not an average village.

35

Forvarious studies of common wares, especially in Italy, see Sagu

`

ı(1998).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

620 s. t. loseby

fine-ware pottery production in late antiquity; these industries often oper-

ated from a number of regional centres and sometimes exported beyond their

immediate localities, but without ever achieving the Mediterranean-wide dis-

tribution of the ARS ware which in some cases they consciously strove to

imitate. In southern Gaul, for example, widespread production of a category

of fine-ware pottery known by a variety of unprepossessing names, including

d

´

eriv

´

ees des sigill

´

ees pal

´

eochr

´

etiennes (DSP) or orange/grey stamped ware, began

late in the fourth century and, in places, continued on into the seventh. These

wares were not greatly exported overseas, unless to the adjacent Mediterranean

coasts of Catalonia and Liguria; even within Gaul their distribution falls into

distinct sub-groups, such that the orange DSP manufactured in Languedoc is

rare in Provence, and vice versa for the grey Provenc¸alvariety.

36

Similarly, in

the eastern Mediterranean, a growing number of fine wares can be identified

which tended to circulate within particular regions, such as the metallescent

ware from Pergamum in Asia Minor, Egyptian versions of Red Slip Ware, or

the Glazed White Ware which emerges at Constantinople and would continue

to dominate the market there for centuries.

37

These regional types were very

occasionally disseminated more widely, but in the East only the Red Slip Ware

produced at Phocaea on the west coast of Asia Minor achieved an international

distribution remotely comparable to that of ARS.

38

Although this tripartite ranking of pottery types – local, regional, interna-

tional – is somewhat crude, the ceramic evidence provides a useful illustration

of the enduring complexities of the economy at the intermediate level, espe-

cially since it is not easy to identify such networks of exchange in the written

sources. Here the distinction between local and regional markets is rarely drawn

as nicely as in Cassiodorus’ description of the commercial connotations of the

feast-day of St Cyprian at a sacred spring near Marcellianum, in Lucania in

southern Italy: ‘all the notable exports of industrious Campania, or opulent

Bruttium, or cattle-rich Calabria, or prosperous Apulia, with the products of

Lucania itself, are on display to the glory of most admirable commerce, such

that you would be right to think that such a mass of goods had been gathered

from many regions’.

39

Such fairs also presumably encouraged the circulation –

and celebratory consumption – of the wine carried in the amphora type known

as Keay lii,now known to have been produced in southern Italy and Sicily.

40

36

Reynolds (1995), pp. 36–7; Rigoir (1998). The distribution patterns of contemporary southern Italian

red-painted wares are similar: Arthur and Patterson (1994).

37

Hayes (1992), pp. 12–34;Panella (1993), pp. 657–61, 673–7;Sodini (1993), pp. 173–4.For Egypt see

Bailey (1998), esp. pp. 8–58.

38

Phocaean Red Slip: Martin (1998). In the East PRS is rare only in Egypt. It also reaches the West,

though never in quantities equivalent to those of ARS in the East: Reynolds (1995), pp. 34–6, 132–5.

39

Cassiodorus, Variae viii.33.

40

Arthur (1989); Pacetti (1998).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Mediterranean economy 621

Only reports of the muggings of visiting merchants by the rascally local peas-

antry spoil the festive scene. Another staple, which may well have circulated

commercially hereabouts, was grain. Pope Gregory I, for example, was peren-

nially anxious to secure grain-supplies for Rome from Sicily, usually through

imperial functionaries or from the extensive papal estates, but he also resorted

to purchasing it on the open market, in 591 spending fifty pounds of gold

on buying up additional supplies from the island for storage in response to a

poor Roman harvest.

41

Across the Apennines, meanwhile, the inhabitants of

Venetia and Istria at the head of the Adriatic were dealing in wine, fish-sauce,

oil and salt, as well as grain; some of these goods were intended for Ravenna,

but they were also traded on the open market.

42

Tw o centuries later the mer-

chants of Comacchio at the head of the Po would secure from the Lombards an

agreement granting them trading rights along the river in exchange for tolls in

kind, among which salt again figures prominently.

43

Salt is precisely the sort of

commodity that one might expect to circulate over some distance – everybody

needs salt, as Cassiodorus observed – but not too far. Its extraction is widely

possible around the Mediterranean, transporting it over long distances by sea

ran the risk of ruining it, and, unlike wine, specific types of salt are not known

to have carried any premium. Its presence in these texts is one indication that

the exchange they describe is regional in nature.

The early medieval Mediterranean thus sustained a series of regional

economies, some of which appear to have been more developed, or more

dynamic, than others. The variable experiences of Italy’s regions, in particular,

already suggest that generalised explanations of economic change, such as the

impact of warfare or of environmental crisis, are insufficient.

44

The extension

of such studies offers our best hope of developing comparative perspectives and

achieving a deeper understanding of early medieval exchange in all its com-

plexity. But for the Mediterranean economy writ large, we must return to the

exchange which continued to unite those who lived around Rome’s Internal

Sea (and even some out in the Ocean) long after the political fragmentation

of its shores. The term ‘long-distance trade’ conventionally used to describe

this type of traffic is not entirely helpful, because, as we have seen, it is not

distance but access to the sea or to navigable waterways that really matters.

In this sense, the inhabitants of the Spanish coast were ‘closer’ to Carthage or

41

Gregory I, Reg. i.70; Arnaldi (1986). Gregory’s anticipation of crisis seems to have been exceptional:

cf. note 30 above.

42

Cassiodorus, Variae xii.22, 24, the latter showing how the inhabitants of Venetia directly exchanged

cylinders of salt for foodstuffs.

43

Hartmann (1904), pp. 123–4, for the text of the early eighth-century Comacchio ‘capitulary’, trans-

lated and discussed in Balzaretti (1996).

44

Wickham (1994), pp. 752–6,Marazzi (1998b), and for the ceramics Sagu

`

ı(1998).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

622 s. t. loseby

Rome than to the high plateaux of the adjacent Meseta; for the same reason, if

we venture out momentarily beyond the Straits of Gibraltar, scattered finds of

Mediterranean ceramics seem more common in sub-Roman western Britain

than in northern Francia. The famous story of how an Alexandrine sea-captain

sailed, however inadvertently, from Egypt to Britain may well be apocryphal,

but the sixth-century ARS and eastern amphorae which link the monastic site

of Kellia in Lower Egypt and Tintagel in Cornwall in a maritime community

of taste are not.

45

Nor should the notion of a voyage from Egypt to Britain

conceal the likelihood that most ‘long-distance’ exchange was carried out in

sundry short hops, either along the coast from port to port, or across the open

sea, exploiting the convenient island stepping-stones across the Mediterranean

pond.

46

The ‘long-distance’ tier of the exchange-system has often been dismissed

as epiphenomenal: luxury in nature, trivial in scale, marginal in importance.

One type of foodstuffs which may fall into this category are the exotic fruits,

nuts and especially spices shipped from the eastern Mediterranean, Arabia

and India to western consumers throughout our period, whether to meet the

enthusiasm of individual hermits for an authentic taste of Egyptian asceticism,

or to cater for the more substantial demands of institutions, most obviously

monastic communities.

47

The Frankish king Chlothar III (657–673) autho-

rised the agents of his newly founded monastery at Corbie to collect annu-

ally a cornucopia of imports – selon arrivage –fromaroyal warehouse in the

Provenc¸alport ofFos.

48

Alongside olive oil, fish-sauce, Spanishanimal skins and

Egyptian papyrus, their shopping-list featured more than a dozen different east-

ern fruits, herbs and spices, totalling 825 pounds in weight. This may appear

trivial when set alongside the 10,000 pounds of oil which heads the list, but it

is worth remembering that this supposedly represents the annual consumption

of a single community. And although the ultimate recipients of such ‘luxuries’

were often institutions, there is little doubt that much exchange of this type

was commercial; Isidore of Seville warned against unscrupulous merchants who

adulterated pepper with shavings of lead or silver to make it more valuable,

simply by weight alone, or because fresh pepper was known to be heavier.

49

45

Leontius, Life of John the Almsgiver c.8.Kellia: Egloff (1977); Ballet and Picon (1987). Tintagel:

Thomas (1981), with the papers in Dark (1995).

46

Documented routes: Roug

´

e(1966), pt 1; Claude (1985), pp. 131–66, with Reynolds (1995), pp. 126–36,

for a stimulating attempt to deduce them from ceramic assemblages, alleging more direct traffic.

Pond: Socrates, in Plato, Phaedo, 109b:‘we inhabit a small portion of the earth . . . living about the

sea like frogs and ants around a pond’.

47

Hermits: Gregory, Hist. vi.6.Monasteries: Lebecq (2000), and also chapter 23 below.

48

Levillain (1902), no. 15,pp.236–7.Recent discussions (with anterior references): Loseby (2000),

pp. 176–89 and (more optimistically) Horden and Purcell (2000), pp. 163–6.

49

Isidore, Etymologiae xvii.8.8.