Engerman S.L., Gallman R.E. The Cambridge Economic History of the United States, Vol. 1: The Colonial Era

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Settlement and Growth of the

Colonies

187

export to the great European markets. In part, the poor demographic

performance of these regions was caused by the geography of disease, as

malaria and other dangerous illnesses spread more readily in warmer cli-

mates. But the demographic problems of these regions were in part a

consequence of their economic opportunities, as the availability of lucra-

tive export crops resulted in harsh labor regimes in which profits could be

increased by forcing laborers to work at levels of effort and under adverse

conditions that damaged their health and reduced their longevity.

Malthus contended "that there is not a truer criterion of the happiness

and innocence of a people than the rapidity of their

increase.

"*«

And he

had no doubt that the extraordinarily rapid growth of the population of

the English North American colonies was due to extraordinarily favorable

economic circumstances, as the availability of vast amounts of fertile land

was combined with political institutions favorable to the improvement

and cultivation of that land.

15

Although quantitative studies of the eco-

nomic and social progress of the colonial population cannot provide direct

measures of their happiness, these studies can tell us how migrants to the

colonies fared materially, and therefore provide indirect evidence on how

the settlement of English America was perceived by contemporaries.

The best systematic evidence on the economic and social progress of the

immigrants comes from several studies that have traced the careers of

sizable groups of indentured servants who migrated to Maryland during

the seventeenth century. How migrants fare at their destination is of

course an important question in the study of

any

migration. In the case of

indentured servants in early America the question seems particularly inter-

esting in view of the great sacrifices they made in order to migrate, giving

up much of their freedom of choice over living and working conditions for

substantial periods, as well as considerably increasing their risk of prema-

ture death both on the ocean voyage and upon arrival in the New World.

The question of whether the servants' gains from migrating could have

justified these high costs was hotly debated by contemporaries, as well as

by many historians in more recent times.

Servants who arrived in Maryland early in the seventeenth century and

who escaped the substantial risk of premature death in the early Chesa-

peake generally prospered: 90 percent of those who arrived in Maryland

during the colony's first decade of settlement and who remained in the

'« Malthus, Essay on Population, 106.

•' Malthus, Essay on Population, 105. This analysis appean to have been drawn from Smith, Wealth of

Nations, 338—9.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

188 David W. Galenson

colony for at least ten years after completing their terms of servitude

became landowners, typically on a scale that afforded them a comfortable

living. Some accumulated considerable wealth, and a few gained estates

that placed them among the wealthiest planters in the

colony.

Nearly all of

these early former servants who remained in Maryland for a decade or more

after gaining their freedom held political office or sat on a jury - not

major positions in most cases, but nonetheless substantially above what

these men could have expected had they remained in England. Several of

these early servants became members of the elite group that ruled early

Maryland, even joining the colony's governing Council. The accomplish-

ments of many of these freedmen were very impressive from an English

perspective; most could not have expected to do nearly as well had they

not emigrated, for England was

a

place that offered little chance of signifi-

cant economic or social mobility for those born below the gentry.

Opportunities for immigrants to Maryland deteriorated over time, how-

ever. Parallel analysis of the careers of a group of servants who arrived in

the colony during the 1660s shows less impressive accomplishments.

More than half of those who remained in Maryland for at least a decade as

freedmen failed to become landowners, and none of these former servants

acquired great wealth. A smaller proportion than of the earlier group

participated in government, and of these none rose above minor public

office. The opportunity for former servants to become prosperous planters

in Maryland was therefore much less late in the seventeenth century than

it had been earlier. Freedmen increasingly faced a choice between remain-

ing in the colony as hired workers or moving elsewhere, most often to

Pennsylvania, in search of their own land.

Several general conclusions might be drawn from these studies of the

success of migrants. One is the simple recognition that the time and

destination chosen by an immigrant were crucial determinants of his

experience. This point, which emerges strongly from the history of

seventeenth-century Maryland, becomes even clearer when differences

among colonial regions are considered: whereas the availability of good

farmland gave Pennsylvania a favorable reputation among immigrants for

a century, the high cost of land and undesirable conditions for hired

workers caused indentured servants and free immigrants of modest means

very early to avoid traveling to the West Indies, and later the Lower

South. But as these decisions by immigrants indicate, information about

the desirability of the different colonial regions spread widely among

Englishmen who were considering moving to America. It was indeed the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Settlement

and

Growth

of the

Colonies

189

choices made by white immigrants to avoid the harsh living and working

conditions of the sugar islands and the rice colonies that made slavery the

economic solution of planters in these regions, for Africans could be forced

to work in places where Europeans chose not to.

A

second generalization from

the studies

of Maryland

is

that although the

degree of economic opportunity available to immigrants declined over time

in the Chesapeake, even in the

final

decades

of the seventeenth century there

was no shortage of employment. Although the rapid expansion of the

tobacco

economy,

which earlier had made the sparsely settled Chesapeake an

excellent place for poor settlers, had given way to slower growth in a more

densely settled region where the choicest land had become occupied, freed-

men could still find abundant work at good wages. This point again seems

subject to wider application: although the extent of opportunity for immi-

grants varied over time and across

places,

colonial English America appears

throughout its history to have remained a genuine land of opportunity

where European migrants might considerably improve their condition if

they were willing to risk premature death in the trans-Atlantic crossing and

the unfamiliar disease environment of the New World. That the colonies

continued to attract large numbers of Europeans, skilled as well as un-

skilled, throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is testimony

to the fact that many Europeans knew this to be true.

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

Our knowledge of the growth of the aggregate colonial economy is poor.

Existing data sources have not been adequate to provide the basis for

reliable estimates of the total product or income of the colonies, so it is not

possible to summarize the colonies' economic growth by presenting time-

series evidence on aggregate colonial output or per capita income. The

best summary evidence on overall colonial economic performance has been

drawn from probate records, as considerable effort has recently been de-

voted to developing estimates of the per capita wealth of the living from

the inventories of the estates of decedents made by colonial probate courts.

Although these wealth estimates cannot be converted convincingly into

estimates of per capita income because of a lack of evidence on savings

rates,

the evidence on wealth is of value in its own right for the insights it

yields into colonial economic performance both over time and in cross-

sectional comparisons among regions.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

190 David

W.

Galenson

The most extensive use of the probate inventories for the estimation of

wealth was made by a study that estimated the wealth of all the English

mainland regions in the single year of 1774. Estimates for earlier years are

scarce, and no comparable study of a large number of colonies has been

done for any other time. Some indications of change over time can be

gained from narrower studies, however. One study recently found that

total wealth per wealthholder in six Maryland tidewater counties in 1700

was £203, and estimated that per capita wealth in these counties at the

same date at £34.7.?* In 1774, total wealth per wealthholder in the

southern mainland colonies was £395, while per capita southern wealth

was £54.7. After adjusting for price-level changes, the estimate of south-

ern real total wealth per wealthholder for 1774 is 49.8 percent higher than

that for Maryland in 1700, while estimated real total wealth per capita in

1774 is 22.6 percent above the estimate for 1700.

17

Comparison of these

figures over time can be no more than suggestive, because the geographic

coverage of the estimates is very different, and the direction of

any

result-

ing bias in comparing the estimates is unknown. The changes in level are

substantial, however, as the implied annual average of growth of wealth

per wealthholder is 0.55 percent between 1700 and 1774, while the

annual average increase of per capita wealth is 0.28 percent. Moreover, it

is likely that these growth rates continued a process that had begun earlier

in the colonial period, for wealth levels were probably considerably higher

in 1700 than in the mid-seventeenth century. The more rapid increase of

wealth per wealthholder than of per capita wealth between 1700 and 1774

is consistent with the increase during the eighteenth century of

the

impor-

tance of slaves in the southern colonies, because slaves increased the total

population without adding to the numbers of wealthholders. Although

obviously imprecise, the indication of growth given by these comparisons

is clearly consistent with the consensus among most economic and social

historians who have studied the colonies, that significant increases oc-

curred during the colonial era in both productivity and the standard of

living.

Although comparable estimates of per capita wealth for the seventeenth

century are lacking, some studies of the value of probated estates provide

suggestive evidence. One of these found that the mean value of estates in

16

All values in this section are given in £ sterling.

" Price-level changes are taken from Henry Phelps Brown and Sheila V. Hopkins, A

Perspective

of

Wages

and

Prices

(London: 1981), 30. Because the wealth estimates are quoted in English currency,

the appropriate price-level adjustments are those of England. .

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Settlement and Growth of the

Colonies

191

Jamaica rose steadily during the last quarter of the seventeenth century,

with the average value in 1700 more than twice that of 1675. A study of

four counties on Maryland's lower western shore found that the mean value

of estates rose by 40 percent between the 1660s and the beginning of the

eighteenth century. Although these increases are impressive, they are not

necessarily the result of economic growth, for to some unknown extent

—

most likely a large extent in Jamaica - they may represent the effects of a

growing concentration of wealth as the number of bound laborers in-

creased. Yet it is likely that in some degree they were caused by genuine

gains in productivity. Early in the colonial period, English settlers in

those regions that differed most from their homeland with respect to

climate and other agricultural endowments began to grow staple crops

that were generally new to them, on a scale that was also unfamiliar. The

potential profits to be made by growing sugar, tobacco, and other crops

more efficiently were great, and might be expected to have led colonists to

work at improving their methods of production. This does seem to have

occurred, as for example in the early Chesapeake planters both learned how

to handle more tobacco plants per worker and developed better strains of

the plant. The results were impressive, as one study found that tobacco

output per worker in Maryland and Virginia more than doubled between

1620 and 1630, and doubled again between 1650 and the end of the

seventeenth century, with the net effect that the amount of the crop

harvested per worker rose from 400 pounds in the early decades of tobacco

cultivation to 1,900 pounds per worker by 1700. This achievement of

early productivity gains was by no means inevitable, however, and it is not

likely to have occurred equally throughout all the colonial regions. In

some regions, particularly those where agricultural conditions differed less

from those of England, there may have been less scope for productivity

increases due to improvements in agricultural methods. A study of two

rural Massachusetts counties, for example, found no increase in mean

wealth per estate between 1680 and 1720. Earlier in this essay, it was seen

that the greatest departures from the originally intended forms of govern-

ment and the greatest modifications in transplanted institutions tended to

occur in those regions where economic conditions differed most from those

of England. Although detailed investigations remain to establish the eco-

nomic effects of these adaptations, it may be that the more radical changes

coincided with, and perhaps served as the basis for, the greatest gains in

productive economic efficiency.

The major study of colonial wealth done to date has estimated that

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

192 David W. Galenson

nonhuman per capita wealth in the mainland colonies in 1774 was £37.4.

Although comparisons with other countries are again difficult, it is possi-

ble to give some indication of where this placed the colonies relative to

England. Per capita wealth in England rose from approximately £110 in

1760 to £192 in 1800.

l8

Per capita wealth therefore appears to have been

substantially lower in America than in England, with the colonial level in

1774 probably significantly less than one-third that of England. Although

little research has been done to evaluate this sizable difference, the author

who produced the colonial estimates cited here suggested that the large

size of this gap in wealth might have been due in part to differences in

social structure and institutions between the mother country and the

colonies, and that the difference in the level of income might consequently

have been smaller than that in wealth:

We are left with the possibility that British wealth per capita, which includes the

wealth of the barons, lords . . . and of other great landed estates, was consider-

ably higher than that of the colonists, including the slave population. Income

may have been higher in relation to wealth in the colonies because of the much

lower value of land here, the importance of "free" income (gathered from the

countryside), the lesser elegance of

the

finer private buildings, the

as

yet relatively

fewer "carriages and coaches," the relatively small amounts of fixed industrial

capital.

•»

Support for the proposition that colonial income levels might have

compared more favorably with that of England than was the case for

wealth is provided by several intriguing pieces of indirect evidence about

one important component of the material standard of living, nutrition. A

recent study of muster rolls for soldiers who fought in the American

Revolution produced the striking result that American-born colonial sol-

diers of the late 1770s were on average more than three inches taller than

their English counterparts who served in the Royal Marines at the same

time.

Since the genetic potential for height in these populations would not

have differed, the most likely cause of this remarkable American advan-

tage in height is superior nutrition. This conclusion becomes somewhat

less surprising in view of another recent study that examined the diet of

colonists in the Chesapeake region, and found that after the very earliest

years of settlement it is likely that nearly all migrants from England to the

18

These figures for national wealth per head are from Charles Feinstein, "Capital Formation in Great

Britain," in Peter Mathias and M. M. Postan, eds., Cambridge

Economic

History of Europe, Vol. VII

(Cambridge: 1978), Table 24, 83; the figures were converted from constant 1851-60 prices to

current prices using the price index given in

ibid.,

Table 5, col. 1, 38.

•'» Alice Hanson Jones, Wealth of a Nation to Be (New York: 1980), 69.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Settlement

and Growth of the

Colonies

193

Chesapeake improved their diets in the process. Although settlers in the

Chesapeake had to adapt to a diet different from the one they knew in

England, with an American diet based primarily on Indian corn instead of

wheat and other grains, most colonists in the Chesapeake received a more

nourishing diet than all but the most affluent Englishmen. These studies

of nutrition together suggest that the real standard of living of typical

colonists might have been higher relative to those of English workers than

has generally been believed in the past, and higher than might be inferred

from the comparison of American and English wealth levels.

Another indication of high colonial standards of living is afforded by

evidence on levels of education. Literacy rates among free adult males in

the colonies were high by contemporary English standards. In the mid-

seventeenth century, about two-thirds of

New

England's adult males were

literate, compared to only one-third of adult males in England. Although

literacy rates were higher in New England than elsewhere in the colonies,

literacy rates for free males in seventeenth-century Virginia were near one-

half,

still above English levels, and literacy rates in Pennsylvania were

probably higher than in Virginia. Literacy rates in a number of colonial

areas appear to have fallen in the late seventeenth century, perhaps as a

result of the increasing geographic dispersion of the population; as new

lands on the frontier were settled, more families had no access to existing

schools, and many new towns initially lacked the wealth to build and

operate schools. Strong evidence of improving education appears in the

eighteenth century, however, as literacy rates rose throughout the main-

land colonies. By the close of the colonial period regional differences still

existed, but they were considerably smaller; adult male literacy in New

England was near 90 percent, and free adult males in Pennsylvania and

Virginia had literacy rates near 70 percent. As in the seventeenth century,

overall literacy rates for free adult males in the colonies in the late eigh-

teenth century were therefore higher than those of England, where adult

male literacy was about 65 percent. Evidence on the extent of literacy

therefore suggests that by contemporary standards English America was

not only initially settled by a well-educated population, but that after an

early decline due to the costs of geographic expansion, the colonial popula-

tion saw considerable improvements in education during the eighteenth

century which kept its levels of literacy above those of England.

While comparisons of colonial living standards with those of England

are plagued by severe problems of measurement, comparisons of wealth

among the colonial regions in 1774 can be made with greater precision.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

194 David W. Galenson

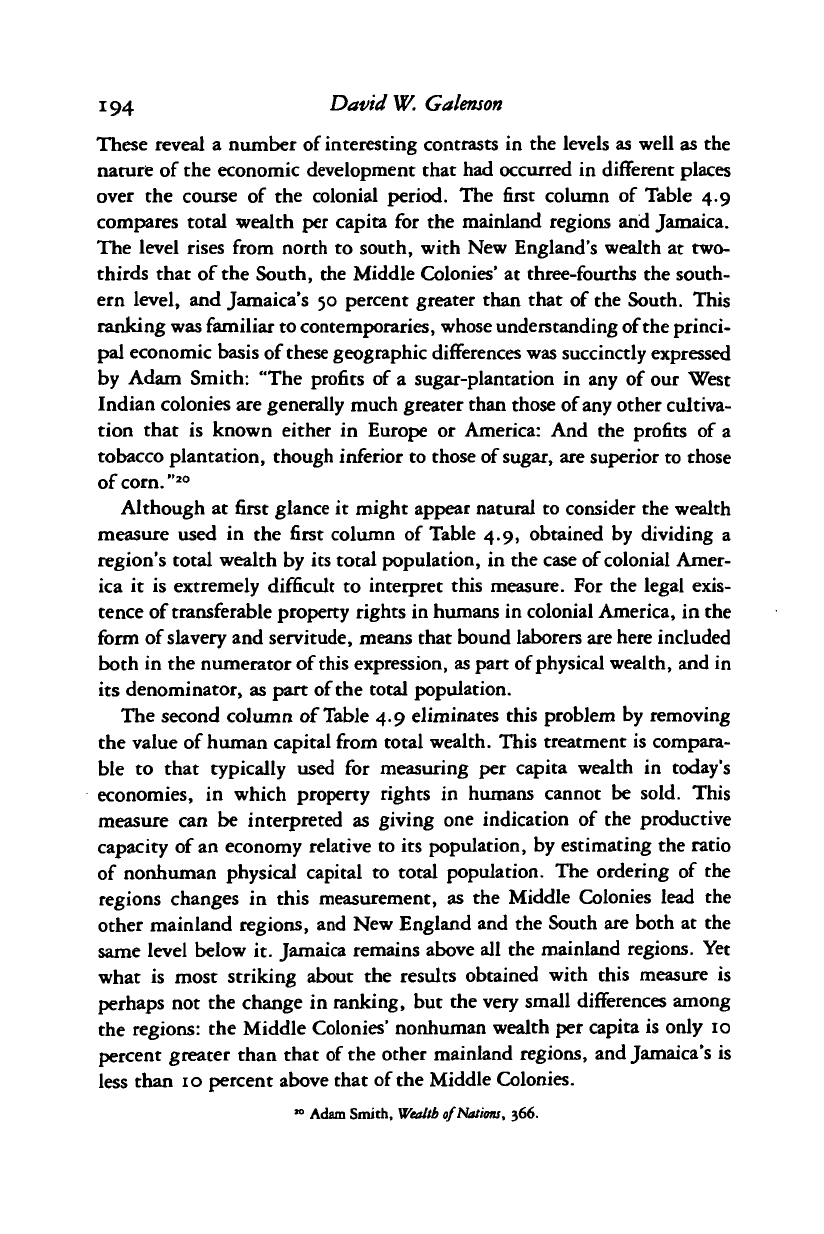

These reveal a number of interesting contrasts in the levels as well as the

nature of the economic development that had occurred in different places

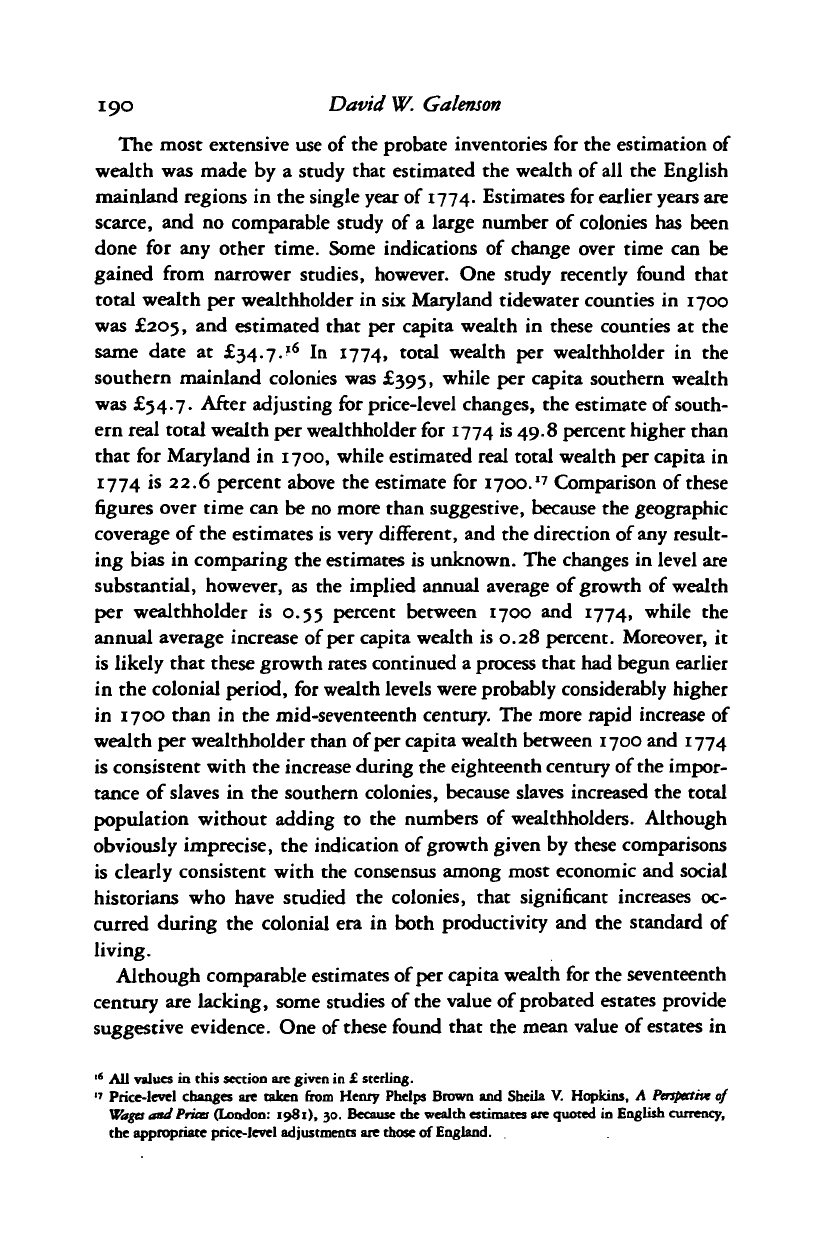

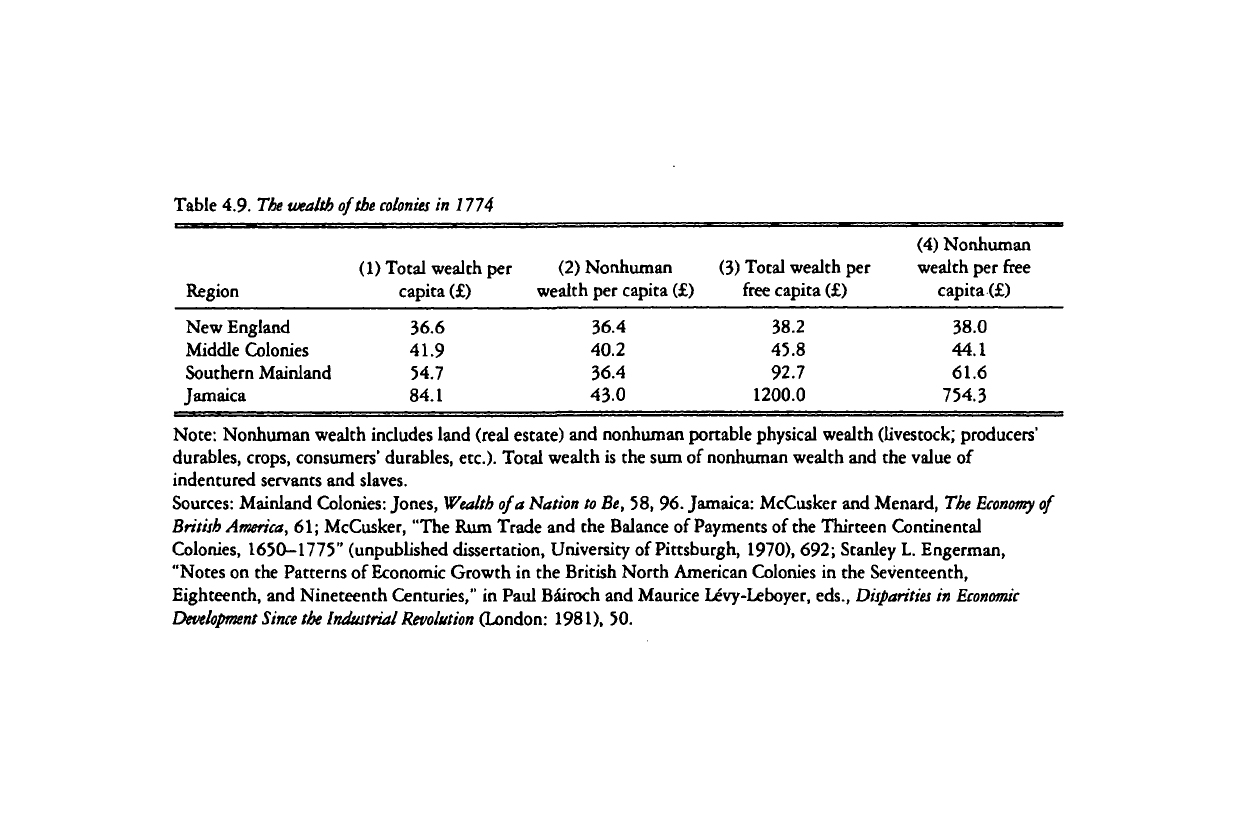

over the course of the colonial period. The first column of Table 4.9

compares total wealth per capita for the mainland regions and Jamaica.

The level rises from north to south, with New England's wealth at two-

thirds that of the South, the Middle Colonies' at three-fourths the south-

ern level, and Jamaica's 50 percent greater than that of the South. This

ranking was familiar to contemporaries, whose understanding of the princi-

pal economic basis of these geographic differences was succinctly expressed

by Adam Smith: "The profits of a sugar-plantation in any of our West

Indian colonies are generally much greater than those of any other cultiva-

tion that is known either in Europe or America: And the profits of a

tobacco plantation, though inferior to those of sugar, are superior to those

of corn."

20

Although at first glance it might appear natural to consider the wealth

measure used in the first column of Table 4.9, obtained by dividing a

region's total wealth by its total population, in the case of colonial Amer-

ica it is extremely difficult to interpret this measure. For the legal exis-

tence of transferable property rights in humans in colonial America, in the

form of slavery and servitude, means that bound laborers are here included

both in the numerator of

this

expression, as part of physical wealth, and in

its denominator, as part of the total population.

The second column of Table 4.9 eliminates this problem by removing

the value of human capital from total wealth. This treatment is compara-

ble to that typically used for measuring per capita wealth in today's

economies, in which property rights in humans cannot be sold. This

measure can be interpreted as giving one indication of the productive

capacity of an economy relative to its population, by estimating the ratio

of nonhuman physical capital to total population. The ordering of the

regions changes in this measurement, as the Middle Colonies lead the

other mainland regions, and New England and the South are both at the

same level below it. Jamaica remains above all the mainland regions. Yet

what is most striking about the results obtained with this measure is

perhaps not the change in ranking, but the very small differences among

the regions: the Middle Colonies' nonhuman wealth per capita is only 10

percent greater than that of the other mainland regions, and Jamaica's is

less than 10 percent above that of the Middle Colonies.

™

Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations, 366.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Table 4.9. The wealth of the

colonies

in 1774

Region

New England

Middle Colonies

Southern Mainland

Jamaica

(1) Total wealth per

capita (£)

36.6

41.9

54.7

84.1

(2) Nonhuman

wealth per capita (£)

36.4

40.2

36.4

43.0

(3) Total wealth per

free capita (£)

38.2

45.8

92.7

1200.0

(4) Nonhuman

wealth per free

capita (£)

38.0

44.1

61.6

754.3

Note: Nonhuman wealth includes land (real estate) and nonhuman portable physical wealth (livestock; producers'

durables, crops, consumers' durables, etc.). Total wealth is the sum of nonhuman wealth and the value of

indentured servants and slaves.

Sources: Mainland

Colonies:

Jones,

Wealth

of a

Nation to

Be,

58,

96.

Jamaica:

McCusker and Menard,

The Economy of

British

America,

61;

McCusker, "The Rum Trade and the Balance of

Payments

of the Thirteen Continental

Colonies, 1650-1775" (unpublished dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, 1970), 692; Stanley L. Engerman,

"Notes on the Patterns of

Economic

Growth in the British North American Colonies in the Seventeenth,

Eighteenth, and Nineteenth Centuries," in Paul Bairoch and Maurice Levy-Leboyer, eds.,

Disparities

in

Economic

Development Since

the Industrial

Revolution

(London: 1981), 50.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

196 David W. Galenson

Comparing columns

1

and 2 of

Table

4.9 serves to emphasize both the

central importance of bound labor in the southern mainland colonies and

the West Indies and the marginality of bound labor in New England and

the Middle Colonies. The difference between the entries for a given region

in the two columns is the value of transferable human wealth in a region

divided by total population, and this ranges from a mere £0.2 in New

England and £1.7 in the Middle Colonies to the much larger amount of

£18.3 in the southern mainland and the still greater value of £41.1 in

Jamaica.

Although informative, the measure presented in the second column of

Table 4.9 fails to capture important aspects of the striking differences in

wealthholding that existed among colonial regions. Since human capital

could be bought and sold under colonial law, servants and slaves repre-

sented valuable physical assets to their owners; at the same time, most

bound laborers were not potential wealthholders. The measure given in

the third column of Table 4.9 recognizes these facts by including the value

of bound laborers in physical wealth while excluding bound laborers from

the population measured in the denominator. The resulting measure gives

an indication of the ratio of the value of total transferable physical wealth

to the size of the free population. The effect of the change in the measure is

dramatic. The initial ranking obtained for total wealth per capita, rising

from north to south, reappears, but what is most striking is again the

relative magnitudes. New England and the Middle Colonies both had less

than half the total wealth per free capita of

the

South. Even more remark-

ably, Jamaica had more than twelve times the average wealth per free

resident of the southern mainland colonies, or equivalently more than

twenty-five times the mean level of the Middle Colonies or New England.

This third measure corresponds most closely to the perceptions of con-

temporaries who compared the wealth of the colonial regions, for what

impressed them was the enormous wealth represented by the great planta-

tions of the southern mainland colonies and the West Indies, in contrast to

the more modest agricultural economies of New England and the Middle

Colonies, which were based on the family farm. Contemporaries were also

aware of the great wealth gap between the West Indies and the southern

mainland, as witnessed for example by Adam Smith's observation that

"our tobacco colonies send us home no such wealthy planters as we see

frequently arrive from our sugar islands."

21

" Smith, Wealth of Nations, 158.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008