Engerman S.L., Gallman R.E. The Cambridge Economic History of the United States, Vol. 1: The Colonial Era

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Settlement

and

Growth

of the

Colonies

197

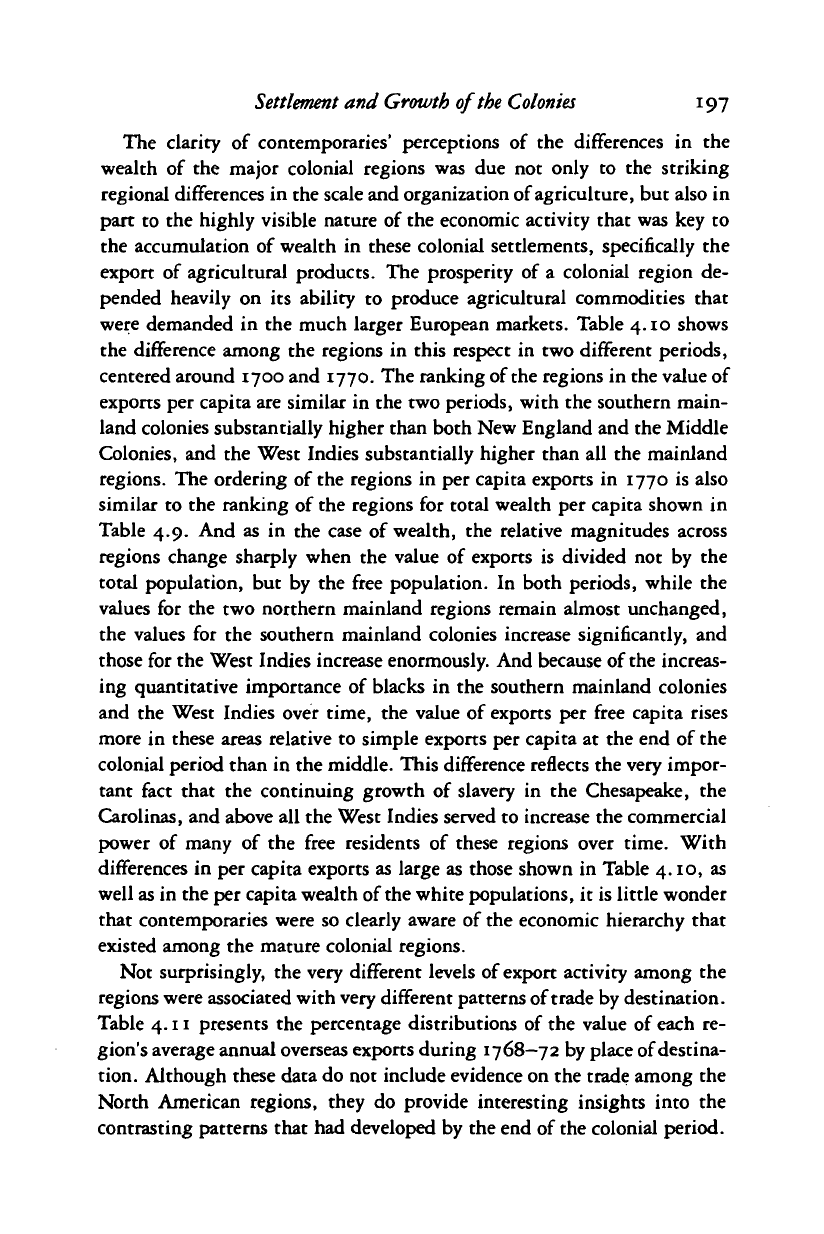

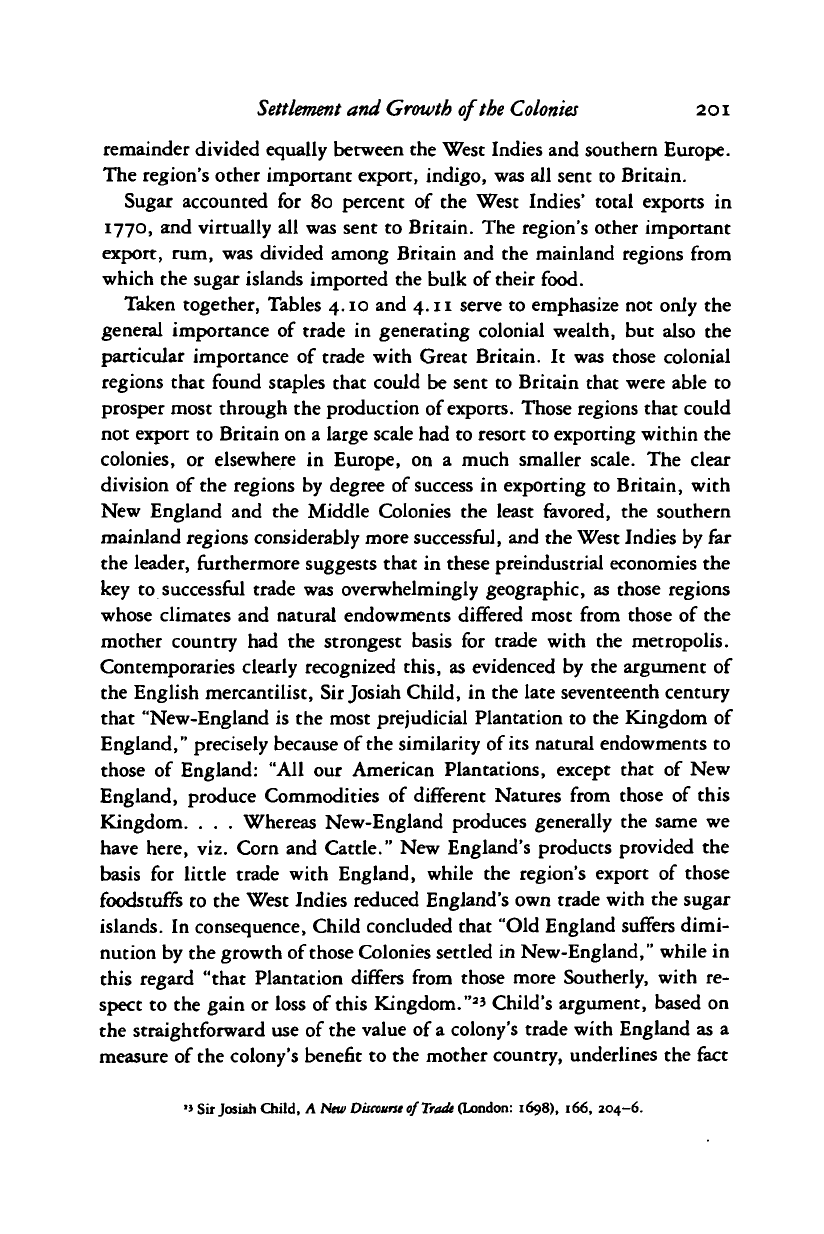

The clarity of contemporaries' perceptions of the differences in the

wealth of the major colonial regions was due not only to the striking

regional differences in the scale and organization of agriculture, but also in

part to the highly visible nature of the economic activity that was key to

the accumulation of wealth in these colonial settlements, specifically the

export of agricultural products. The prosperity of a colonial region de-

pended heavily on its ability to produce agricultural commodities that

were demanded in the much larger European markets. Table 4.10 shows

the difference among the regions in this respect in two different periods,

centered around 1700 and 1770. The ranking of the regions in the value of

exports per capita are similar in the two periods, with the southern main-

land colonies substantially higher than both New England and the Middle

Colonies, and the West Indies substantially higher than all the mainland

regions. The ordering of the regions in per capita exports in 1770 is also

similar to the ranking of the regions for total wealth per capita shown in

Table 4.9. And as in the case of wealth, the relative magnitudes across

regions change sharply when the value of exports is divided not by the

total population, but by the free population. In both periods, while the

values for the two northern mainland regions remain almost unchanged,

the values for the southern mainland colonies increase significantly, and

those for the West Indies increase enormously. And because of the increas-

ing quantitative importance of blacks in the southern mainland colonies

and the West Indies over time, the value of exports per free capita rises

more in these areas relative to simple exports per capita at the end of the

colonial period than in the middle. This difference reflects the very impor-

tant fact that the continuing growth of slavery in the Chesapeake, the

Carolinas, and above all the West Indies served to increase the commercial

power of many of the free residents of these regions over time. With

differences in per capita exports as large as those shown in Table 4.10, as

well as in the per capita wealth of the white populations, it is little wonder

that contemporaries were so clearly aware of the economic hierarchy that

existed among the mature colonial regions.

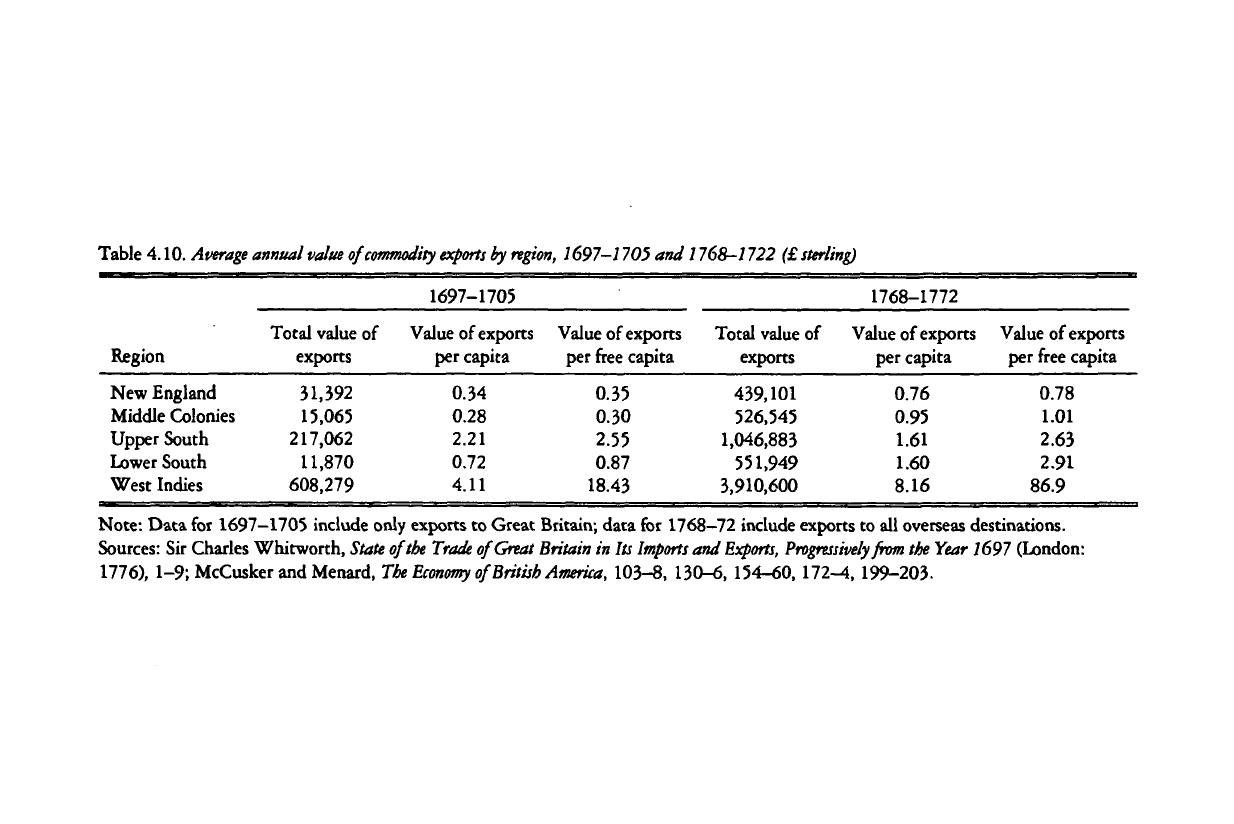

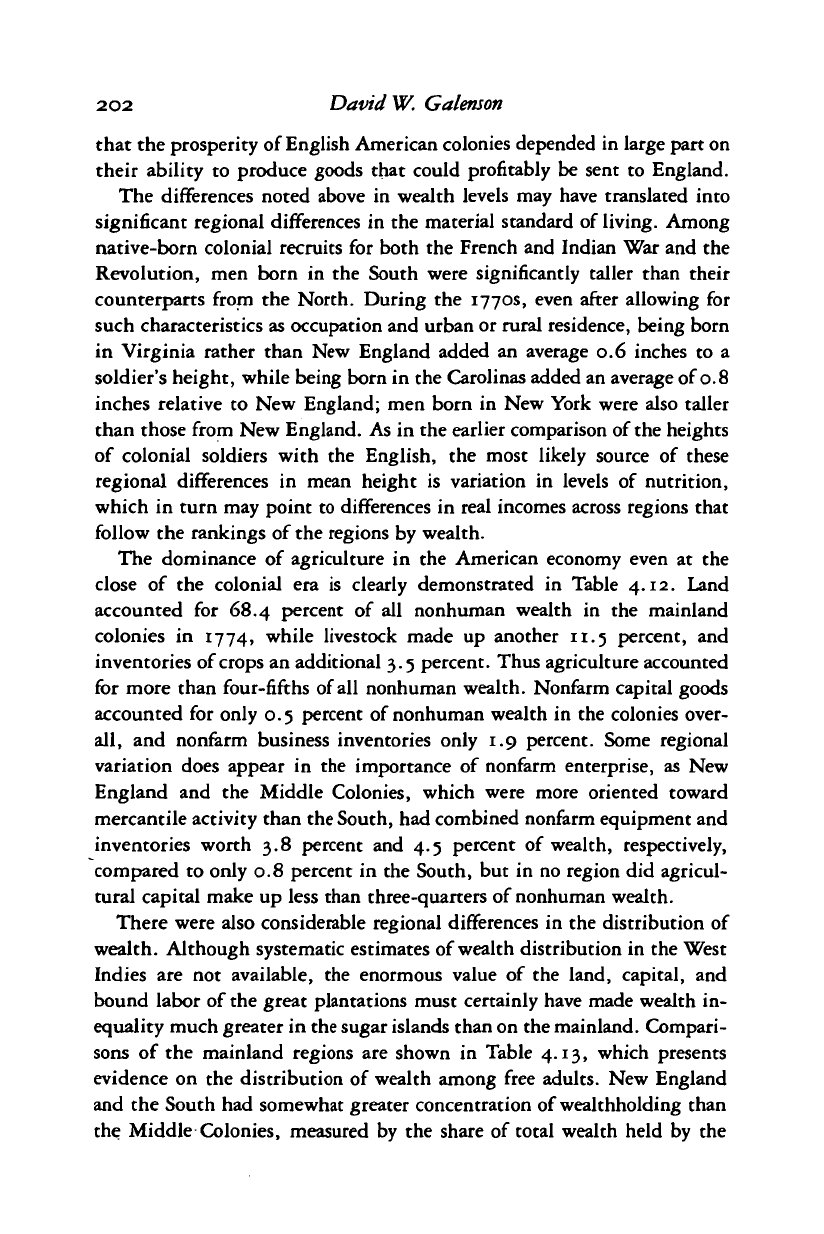

Not surprisingly, the very different levels of export activity among the

regions were associated with very different patterns of trade by destination.

Table 4.11 presents the percentage distributions of the value of each re-

gion's average annual overseas exports during 1768—72 by place of destina-

tion. Although these data do not include evidence on the trade among the

North American regions, they do provide interesting insights into the

contrasting patterns that had developed by the end of the colonial period.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Table 4.10.

Average

annual

value

of

commodity exports

by

region,

1697—1705 and 1768-1722 (£

sterling)

1697-1705

1768-1772

Region

New England

Middle Colonies

Upper South

Lower South

West Indies

Total value of

exports

31,392

15,065

217,062

11,870

608,279

Value of exports

per capita

0.34

0.28

2.21

0.72

4.11

Value of exports

per free capita

0.35

0.30

2.55

0.87

18.43

Total value of

exports

439,101

526,545

1,046,883

551,949

3,910,600

Value of exports

per capita

0.76

0.95

1.61

1.60

8.16

Value of exports

per free capita

0.78

1.01

2.63

2.91

86.9

Note: Data for 1697-1705 include only exports to Great Britain; data for 1768-72 include exports to all overseas destinations.

Sources: Sir Charles Whitworth, State of the

Trade

of Great Britain in Its

Imports

and

Exports,

Progressively from the Year 1697 (London:

1776),

1-9; McCusker and Menard,

The Economy

of

British

America,

103-8, 130-6, 154-60,

172^1,

199-203.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Table

4.11.

Percentage distributions

of the

value

of

average

annual

regional exports by

destination,

1768-

7772

Exporting region

New England

Middle Colonies

Upper South

Lower South

West Indies

Great Britain

and Ireland

18

23

82

72

87

Southern

Europe

15

35

9

10

0

West Indies

63

42

9

18

0

Africa

4

0

0

0

0

North

America

—

—

—

—

13

Total

100

100

100

100

100

Note: For North American mainland colonies, exports to other mainland colonies were not

measured, and are consequently not included in this tabulation.

Source: McCusker and Menard,

The Economy

of

British

America,

108, 130,160,175,199.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

200 David W. Galenson

New England's major overseas trading partner from very early in the

colonial period was the West Indies, which received nearly two-thirds of

all New England's exports. The economy of early Massachusetts enjoyed

substantial continuing flows of immigrants throughout the 1630s, and

during this time many of the earliest settlers prospered by selling cattle

and other agricultural products to more recent arrivals. When political

prospects for Puritans in England improved in the early 1640s, however,

the rate of immigration to New England dropped sharply. Deprived of the

infusions of capital provided by new settlers, Massachusetts' economy

became depressed, and land and cattle prices fell abruptly. The colony's

government searched in vain for a new source of

prosperity,

passing laws

aimed at promoting such activities as the fur trade, iron manufacturing,

and cloth production, but no successful solution was found until New

England merchants became aware of

the

increasing need for food that had

arisen in the West Indies in the wake of that region's sugar revolution.

Boston merchants began to trade with the West Indies in the mid-1640s.

In 1647

a

correspondent from the islands wrote to John Winthrop in

Massachusetts that "Men are so intent upon planting sugar that they had

rather buy foode at very deare rates than produce it by labour, so infinite is

the profit of sugar workes after once accomplished."

22

New England began

to send a variety of foods to the West Indies, with fish, meats, and grain

the most important, and this trade continued throughout the remainder of

the colonial period. Some parts of the region, including the Narragansett

Country in southern Rhode Island, prospered by specializing in raising

cattle for export to the Caribbean islands. The Middle Colonies later

joined New England's farmers and merchants in benefiting from the West

Indies' monoculture in sugar. The Middle Colonies' major export, grain,

went in approximately equal amounts to the West Indies and southern

Europe. The Middle Colonies also sent meat and other food to the West

Indies on a smaller scale.

The trade of the Upper South from a very early date was dominated by

tobacco, which made up more than 70 percent of the region's total exports

even in 1770, and all of which was sent to Britain. The region's much

smaller volume of exports to the West Indies and southern Europe con-

sisted almost entirely of

grain.

Rice made up more than half of

all

exports

from the Lower South; two-thirds of this was sent to Britain, with the

" Quoted in Harold Innis, The Cod

Fisheries

(Toronto: 1954), 78.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Settlement

and Growth of the

Colonies

201

remainder divided equally between the West Indies and southern Europe.

The region's other important export, indigo, was all sent to Britain.

Sugar accounted for 80 percent of the West Indies' total exports in

1770,

and virtually all was sent to Britain. The region's other important

export, rum, was divided among Britain and the mainland regions from

which the sugar islands imported the bulk of their food.

Taken together, Tables 4.10 and 4.11 serve to emphasize not only the

general importance of trade in generating colonial wealth, but also the

particular importance of trade with Great Britain. It was those colonial

regions that found staples that could be sent to Britain that were able to

prosper most through the production of exports. Those regions that could

not export to Britain on a large scale had to resort to exporting within the

colonies, or elsewhere in Europe, on a much smaller scale. The clear

division of the regions by degree of success in exporting to Britain, with

New England and the Middle Colonies the least favored, the southern

mainland regions considerably more successful, and the West Indies by far

the leader, furthermore suggests that in these preindustrial economies the

key to successful trade was overwhelmingly geographic, as those regions

whose climates and natural endowments differed most from those of the

mother country had the strongest basis for trade with the metropolis.

Contemporaries clearly recognized this, as evidenced by the argument of

the English mercantilist,

Sir

Josiah Child, in the late seventeenth century

that "New-England is the most prejudicial Plantation to the Kingdom of

England," precisely because of the similarity of its natural endowments to

those of England: "All our American Plantations, except that of New

England, produce Commodities of different Natures from those of this

Kingdom. . . . Whereas New-England produces generally the same we

have here, viz. Corn and Cattle." New England's products provided the

basis for little trade with England, while the region's export of those

foodstuffs to the West Indies reduced England's own trade with the sugar

islands. In consequence, Child concluded that "Old England suffers dimi-

nution by the growth of

those

Colonies settled in New-England," while in

this regard "that Plantation differs from those more Southerly, with re-

spect to the gain or loss of this Kingdom."

2

' Child's argument, based on

the straightforward use of the value of

a

colony's trade with England as a

measure of the colony's benefit to the mother country, underlines the fact

»» Sir Josiah Child, A New

Discourse

of

Trade

(London: 1698), 166, 204-6.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

202 David W. Galenson

that the prosperity of English American colonies depended in large part on

their ability to produce goods that could profitably be sent to England.

The differences noted above in wealth levels may have translated into

significant regional differences in the material standard of

living.

Among

native-born colonial recruits for both the French and Indian War and the

Revolution, men born in the South were significantly taller than their

counterparts from the North. During the 1770s, even after allowing for

such characteristics as occupation and urban or rural residence, being born

in Virginia rather than New England added an average 0.6 inches to a

soldier's height, while being born in the Carolinas added an average of 0.8

inches relative to New England; men born in New York were also taller

than those from New England. As in the earlier comparison of

the

heights

of colonial soldiers with the English, the most likely source of these

regional differences in mean height is variation in levels of nutrition,

which in turn may point to differences in real incomes across regions that

follow the rankings of the regions by wealth.

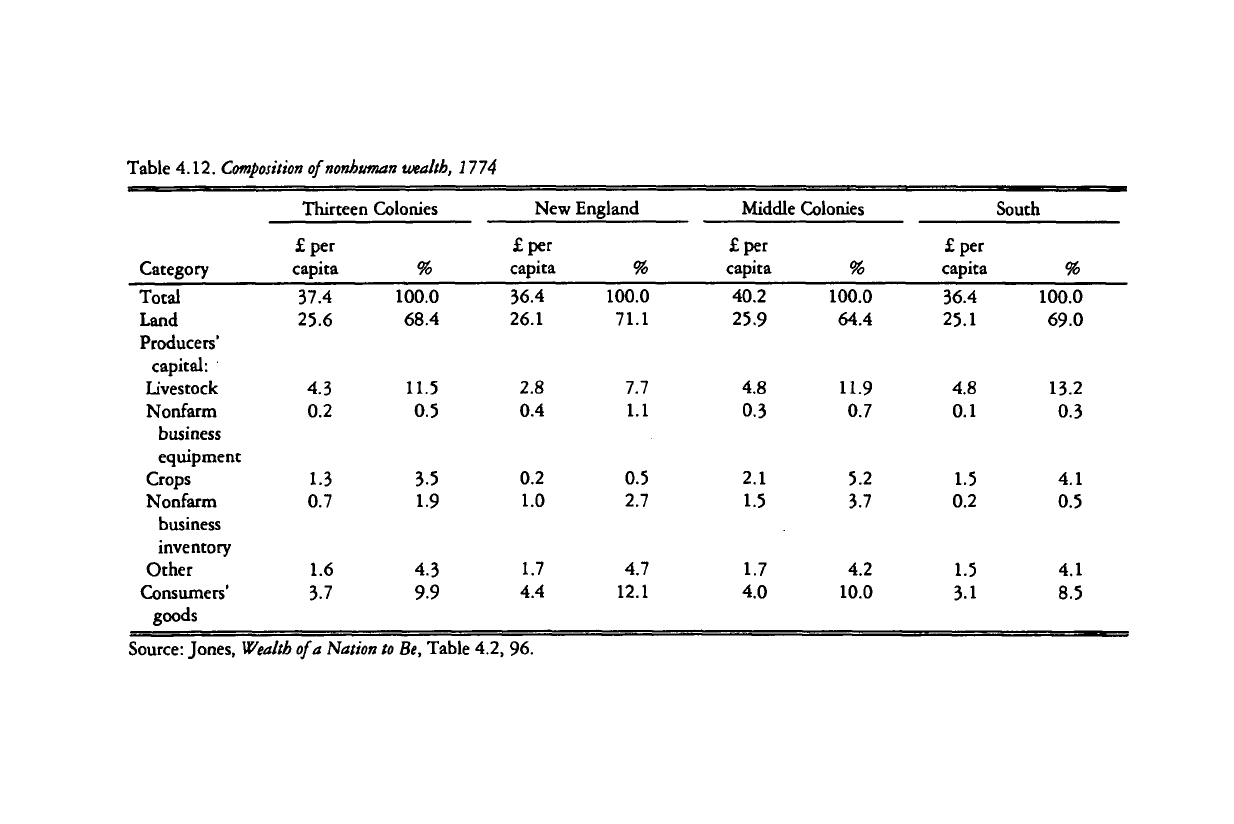

The dominance of agriculture in the American economy even at the

close of the colonial era is clearly demonstrated in Table 4.12. Land

accounted for 68.4 percent of all nonhuman wealth in the mainland

colonies in 1774, while livestock made up another 11.5 percent, and

inventories of crops an additional 3.5 percent. Thus agriculture accounted

for more than four-fifths of

all

nonhuman wealth. Nonfarm capital goods

accounted for only 0.5 percent of nonhuman wealth in the colonies over-

all,

and nonfarm business inventories only 1.9 percent. Some regional

variation does appear in the importance of nonfarm enterprise, as New

England and the Middle Colonies, which were more oriented toward

mercantile activity than the South, had combined nonfarm equipment and

inventories worth 3.8 percent and 4.5 percent of wealth, respectively,

compared to only 0.8 percent in the South, but in no region did agricul-

tural capital make up less than three-quarters of nonhuman wealth.

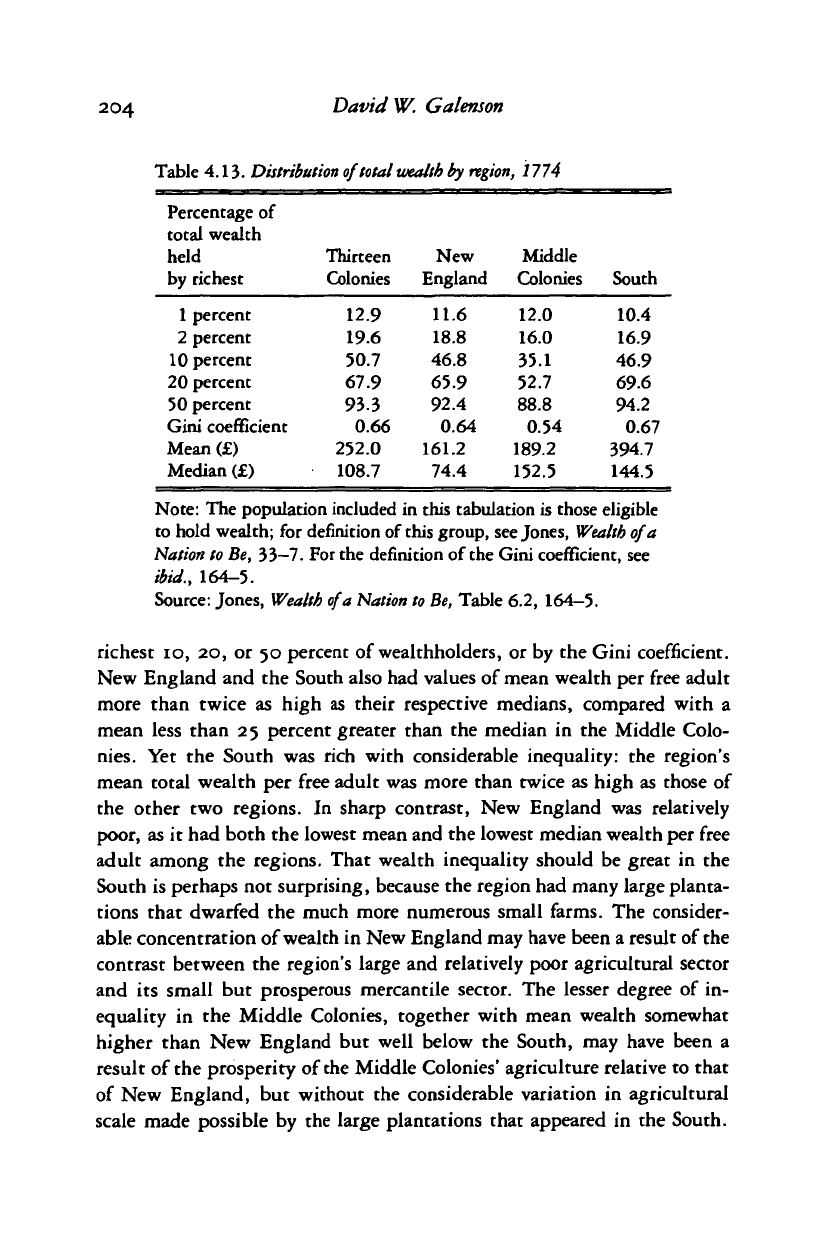

There were also considerable regional differences in the distribution of

wealth. Although systematic estimates of wealth distribution in the West

Indies are not available, the enormous value of the land, capital, and

bound labor of the great plantations must certainly have made wealth in-

equality much greater in the sugar islands than on the mainland. Compari-

sons of the mainland regions are shown in Table 4.13, which presents

evidence on the distribution of wealth among free adults. New England

and the South had somewhat greater concentration of wealthholding than

the Middle Colonies, measured by the share of total wealth held by the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Table

4.12.

Category

Composition

of

nonhuman

wealth,

1774

Thirteen Colonies

£per

capita

%

New

England

£per

capita

%

Middle Colonies

£per

capita

%

South

£per

capita

%

Total

Land

Producers'

capital:

Livestock

Nonfarm

business

equipment

Crops

Nonfarm

business

inventory

Other

Consumers'

goods

37.4

25.6

4.3

0.2

1.3

0.7

1.6

3.7

100.0

68.4

11.5

0.5

3.5

1.9

4.3

9.9

36.4

26.1

2.8

0.4

0.2

1.0

1.7

4.4

100.0

71.1

7.7

1.1

0.5

2.7

4.7

12.1

40.2

25.9

4.8

0.3

2.1

1.5

1.7

4.0

100.0

64.4

11.9

0.7

5.2

3.7

4.2

10.0

36.4

25.1

4.8

0.1

1.5

0.2

1.5

3.1

100.0

69.0

13.2

0.3

4.1

0.5

4.1

8.5

Source:

Jones,

Wealth

of a

Nation to

Be,

Table

4.2, 96.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

204 David W. Galensm

Table 4.13.

Distribution

of

total wealth by

region,

1774

Percentage of

total wealth

held

by richest

1 percent

2 percent

10 percent

20 percent

50 percent

Gini coefficient

Mean (£)

Median (£)

Thirteen

Colonies

12.9

19.6

50.7

67.9

933

0.66

252.0

108.7

New

England

11.6

18.8

46.8

65.9

92.4

0.64

161.2

74.4

Middle

Colonies

12.0

16.0

35.1

52.7

88.8

0.54

189.2

152.5

South

10.4

16.9

46.9

69.6

94.2

0.67

394.7

144.5

Note: The population included in this tabulation is those eligible

to hold wealth; for definition of this group,

see

Jones,

Wealth

of a

Nation to

Be,

33—7.

For the definition of the Gini coefficient, see

ibid.,

164-5.

Source: Jones,

Wealth

of a

Nation to

Be,

Table 6.2, 164-5.

richest io, 20, or 50 percent of wealthholders, or by the Gini coefficient.

New England and the South also had values of mean wealth per free adult

more than twice as high as their respective medians, compared with a

mean less than 25 percent greater than the median in the Middle Colo-

nies.

Yet the South was rich with considerable inequality: the region's

mean total wealth per free adult was more than twice as high as those of

the other two regions. In sharp contrast, New England was relatively

poor, as it had both the lowest mean and the lowest median wealth per free

adult among the regions. That wealth inequality should be great in the

South is perhaps not surprising, because the region had many large planta-

tions that dwarfed the much more numerous small farms. The consider-

able concentration of wealth in New England may have been a result of the

contrast between the region's large and relatively poor agricultural sector

and its small but prosperous mercantile sector. The lesser degree of in-

equality in the Middle Colonies, together with mean wealth somewhat

higher than New England but well below the South, may have been a

result of the prosperity of the Middle Colonies' agriculture relative to that

of New England, but without the considerable variation in agricultural

scale made possible by the large plantations that appeared in the South.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Settlement

and

Growth

of the

Colonies

205

Notwithstanding these regional differences within the colonies in

wealth inequality, it is likely that overall economic inequality was consid-

erably less in the mainland colonies than in England at the time. Visiting

contemporaries almost unanimously described colonial America, particu-

larly the northern mainland regions, as a remarkably egalitarian society,

and regularly commented on both the greater incidence of property owner-

ship and the more limited extent of extreme poverty in the colonies than

in Europe. When a visitor to Pennsylvania in 1775 remarked that "it was

the best country in the world for people of small fortunes, or in other

words, the best poor man's country," he was echoing the words of many

earlier immigrants who had contrasted their new homeland with the old in

letters to relatives and friends who remained behind.

24

Although careful

quantitative comparisons have yet to be carried out, contemporaries' per-

ceptions were probably correct, and modern historians generally believe

that wealthholding was considerably less concentrated in colonial America

than in England.

Another important question on which little systematic research has

been done concerns possible trends in the extent of economic inequality

that occurred during the course of the colonial period. No studies of

overall wealth inequality throughout the colonies are available for dates

prior to 1774. Yet a number of investigations have measured changes in

the distribution of wealth over time within particular communities. On

the basis of studies that found rising wealth concentration in specific

communities, including several large cities and prosperous rural counties

settled early in the colonial period, a number of

scholars

have argued that

wealth inequality probably rose throughout the mainland colonies during

much of the colonial period. Recently, however, this hypothesis of rising

overall colonial inequality has been challenged by an analysis that argues

that this generalization from the local studies is flawed by a fallacy of

composition. The new analysis recognizes that inequality was rising in

cities and in older agrarian regions along the Atlantic coast. Equally

significant for overall inequality, however, was the fact that new frontier

communities were being settled at very rapid rates during most of the

colonial period. The settlers in these new communities were drawn by the

economic opportunities offered by the frontier. Per capita wealth grew

** Quoted in Jackson Turner Main,

The Social Structure

of

Revolutionary America

(Princeton, NJ: 1965),

222.

For an earlier example of this description, see Susan E. Klepp and Billy G. Smith, eds., The

Itifortutiatt: The

Voyage

and

Adventures

of William

Moraley,

an Indentured Servant (University Park, PA:

1992),

88-9.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

206 David W. Galenson

more rapidly in the new frontier communities than in the older coastal

settlements, and because the settlers in the newer communities were

initially poorer on average than the residents of older cities and towns, the

effect of this rapid growth in wealth on the frontier was to reduce overall

colonial inequality. The geographic redistribution of the colonial popula-

tion away from the Atlantic seacoast therefore served to reduce economic

inequality by offering younger, poorer, and more ambitious migrants from

older communities the opportunity to achieve greater economic success by

developing the frontier. Quantitatively, the impact of this redistribution

of population may have been large enough to counterbalance the rising

economic inequality that has been observed within some older communi-

ties,

and the net effect may have been to produce relatively little change in

overall wealth inequality in the mainland colonies throughout most of the

colonial period.

The economic development of the colonies of English America was

surely rapid by preindustrial standards, and as in the case of population

growth this was clearly recognized by contemporaries. Adam Smith began

his general analysis of the economic growth of colonial regions with the

proposition that "the colony of a civilized nation which takes possession of

a waste country, or of one so thinly inhabited, that the natives easily give

place to the settlers, advances more rapidly to wealth and greatness than

any other human society."

2

' And Smith left no doubt as to the principal

evidence on which he based this generalization, stating that "there are no

colonies of which the progress has been more rapid than that of the

English in North America."

26

From a series of small settlements fighting

for their survival in the early seventeenth century, the English colonies

both in the West Indies and on the North American mainland reached

levels of economic development that afforded not only great riches for the

economic elite, but widespread levels of more modest but nonetheless

significant economic prosperity for many European settlers and their de-

scendants. Yet it is clear that the differences in the process of develop-

ment, and in the nature of the economies and societies that emerged, were

enormous among the regions that have been treated here. At one end of

a

spectrum lay New England, which had the least wealth, the least foreign

trade, and the least bound labor among all the regions. At the opposite

end lay the West Indies, where the greatest volume of trade produced the

greatest physical wealth, and the greatest amount of the harshest form of

"» Smith, Wealth of Nations, 531-2.

a6

Smith, Wealth 0/Nations, 538.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008