Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Massie, Robert K. (2000). Nicholas and Alexandra. New

York: Ballantine Books.

N

ICHOLAS

G

ANSON

ALEXANDROV, GRIGORY

ALEXANDROVICH

(1903–1983), pseudonym of Grigory A. Mormo-

nenko, Soviet film director.

The leading director of musical comedies in the

Stalin era, Alexandrov began his artistic career as

a costume and set designer for a provincial opera

company. By 1921, he was a member of the Pro-

letkult theater in Moscow, where he met Sergei

Mikhailovich Eisenstein. Alexandrov served as as-

sistant director on all of Eisenstein’s silent films and

took part in an ill-fated trip to Hollywood and Mex-

ico, which lasted from 1929 to 1932 and ended in

Eisenstein’s disgrace and the entourage’s forced re-

turn home.

After this debacle, Alexandrov found it prudent

to strike out on his own as a film director. By re-

turning to his artistic roots in musical theater, he

found a way to work successfully within the stric-

tures of Socialist Realism by adapting the conven-

tions of the Hollywood musical comedy to Soviet

realities. His films from this era were The Jolly Fel-

lows (1934), The Circus (1936), Volga, Volga (1938),

and The Shining Path (1940), all of which enjoyed

great popularity with Soviet audiences at a time

when entertainment was sorely needed. Central to

the success of these movies were the cheerful songs

by composer Isaak Dunaevsky’s and the comedic

talents of Liubov Orlova, Alexandrov’s leading lady

and wife.

Alexandrov was a great favorite of Stalin’s, and

was named People’s Artist of the USSR in 1948, the

country’s highest award for artistic achievement.

Although Alexandrov continued to direct feature

films until 1960, his most notable post-war ven-

ture was the Cold War classic, Meeting on the Elba

(1949). This film was quite a departure from his

oeuvre of the 1930s. Alexandrov’s final two pro-

jects were tributes. He honored the mentor of his

youth by restoring and reconstructing the frag-

ments of Eisenstein’s Que Viva Mexico! (1979), and

he commemorated his wife’s life and art in Liubov

Orlova (1983).

See also: EISENSTEIN, SERGEI MIKHAILOVICH; MOTION PIC-

TURES; ORLOVA, LYUBOV PETROVNA; PROLETKULT;

SOCIALIST REALISM

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kenez, Peter. (2001). Cinema and Soviet Society from the

Revolution to the Death of Stalin. London: I.B. Tauris.

D

ENISE

J. Y

OUNGBLOOD

ALEXEI I, PATRIARCH

(1877–1970), patriarch of the Russian Orthodox

Church from January 31, 1945, to April 17, 1970.

Sergei Vladimirovich Simansky took monastic

vows in 1902. He served as rector in several sem-

inaries and was subsequently made a bishop. He

became metropolitan in Leningrad in 1933 and en-

dured the German siege of that city during World

War II. According to eyewitness accounts of his sit-

uation in 1937, he anticipated arrest at any mo-

ment, for virtually all of his fellow priests had been

seized by then. He celebrated the liturgy with the

only deacon left in Leningrad, and even that core-

ligionist soon died. During the siege of the city he

lived on the edge of starvation. The members of the

cathedral choir were dying around him, and the

choirmaster himself died in the middle of a church

service. Alexei himself barely had the strength to

clear a path to the cathedral through the snow in

winter.

Under war-time pressures, Stalin permitted the

election of a patriarch, but the one chosen soon died.

Alexei was elected in January 1945. He reopened a

few seminaries and convents and consecrated some

new bishops. Of the parishes that were still func-

tioning at the time, most were in territories that

had been recently annexed or reoccupied by the

USSR. In fact, one could travel a thousand kilome-

ters on the Trans-Siberian Railroad without pass-

ing a single working church. The later anti-religious

campaign of communist general secretary Nikita

Khrushchev resulted in the closing of almost half of

those churches still functioning in the 1950s.

Alexei reached out to Orthodox religious com-

munities abroad. He was active in the World Peace

movement, supporting Soviet positions. The Russ-

ian Church joined the World Council of Churches,

and Alexei cultivated good relations with Western

Protestants. He was criticized for his cooperation

with the Soviet regime, but no doubt believed that

ALEXEI I, PATRIARCH

43

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

collaboration was necessary for the church’s sur-

vival.

See also: LENIGRAD, SIEGE OF; PATRIARCHATE; RUSSIAN OR-

THODOX CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Davis, Nathaniel. (1995). A Long Walk to Church. Boul-

der, CO: Westview Press.

N

ATHANIEL

D

AVIS

ALEXEI II, PATRIARCH

(b. 1929), secular name Alexei Mikhailovich Ridi-

ger, primate of the Russian Orthodox Church

(1990– ).

Born in Tallinn, of Russian and Baltic German

extraction, Alexei graduated from the Leningrad

Theological Seminary in 1949 and was ordained in

1950. In 1961 he was consecrated bishop of Esto-

nia, and later appointed chancellor of the Moscow

Patriarchate (1964). In 1986 he became metropol-

itan of Leningrad, and was elected patriarch on

June 7, 1990.

From his election to early 2003, over 13,000

parishes and 460 monasteries were established. A

decade after his enthronement, nearly three-quarters

of Russians considered themselves members of the

church (although only 6% were active churchgo-

ers), and the patriarch enjoyed high approval rat-

ings as the perceived spokesman for Russia’s

spiritual traditions.

Alexei, a former USSR people’s deputy, envi-

sioned a partnership between church and state to

promote morality and the popular welfare. He met

regularly with government officials to discuss pol-

icy, and signed agreements with ministries detail-

ing plans for church-state cooperation in fields such

as education. His archpastoral blessing of Boris Yeltsin

after his 1991 election began a relationship between

patriarch and president that continued under Vladi-

mir Putin. Alexei saw the church as essential for pre-

serving civil peace in society, and used his position

to promote dialogue among various parties, gaining

much credibility after trying to mediate the 1993

standoff between Yeltsin and the Supreme Soviet.

Alexei’s leadership was not without contro-

versy. Some have voiced concerns that the church

was too concerned with institutional status at the

expense of pursuing genuine spiritual revival. Busi-

ness ventures designed to raise funds for a cash-

strapped church were called into question. Alexei

was criticized for his role in promoting the 1997

legislation On Religious Freedom which placed lim-

itations on the rights of nontraditional faiths. Al-

legations surfaced about KGB collaboration (under

the codename Drozdov), something he consistently

denied. He justified his Soviet-era conduct (one

CPSU document described him as “most loyal”) as

necessary to keep churches from closing down. De-

fenders note that he was removed as chancellor af-

ter appealing to Mikhail Gorbachev to reintroduce

religious values into Soviet society.

Alexei was outspoken in his determination to

preserve the Moscow Patriarchate as a unified en-

tity, eschewing the creation of independent

churches in the former Soviet republics. Although

most parishes in Ukraine remained affiliated to

Moscow, two other Orthodox jurisdictions com-

peted for the allegiance of the faithful. When the

Estonian government turned to Ecumenical Patri-

arch Bartholomew to restore a church administra-

tion independent of Moscow’s authority, Alexei

briefly broke communion with him (1996), but

agreed to a settlement creating two jurisdictions in

Estonia.

The patriarch worked to preserve a balance be-

tween liberal and conservative views within the

church. The Jubilee Bishops’ Council (2000) rati-

fied a comprehensive social doctrine that laid out

positions on many issues ranging from politics (of-

fering a qualified endorsement of democracy) to

bioethics. Compromises on other contentious ques-

tions (participation in the ecumenical movement,

the canonization of Nicholas II, and so forth) were

also reached. In the end, the council reaffirmed

Alexei’s vision that the church should emerge as a

leading and influential institution in post-Soviet

Russian society.

See also: PATRIARCHATE; RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alimov, G., and Charodeyev, G. (1992). “Patriarch Alek-

sei II: ‘I Take Responsibility for All That Happened.’”

Religion, State, and Society 20(2):241–246.

Bourdeaux, Michael. (1992). “Patriarch Aleksei II: Be-

tween the Hammer and the Anvil.” Religion, State,

and Society 20(2):231–236.

Pospielovsky, Dimitry. (1998). The Orthodox Church in the

History of Russia. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s

Seminary Press.

N

IKOLAS

K. G

VOSDEV

ALEXEI II, PATRIARCH

44

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

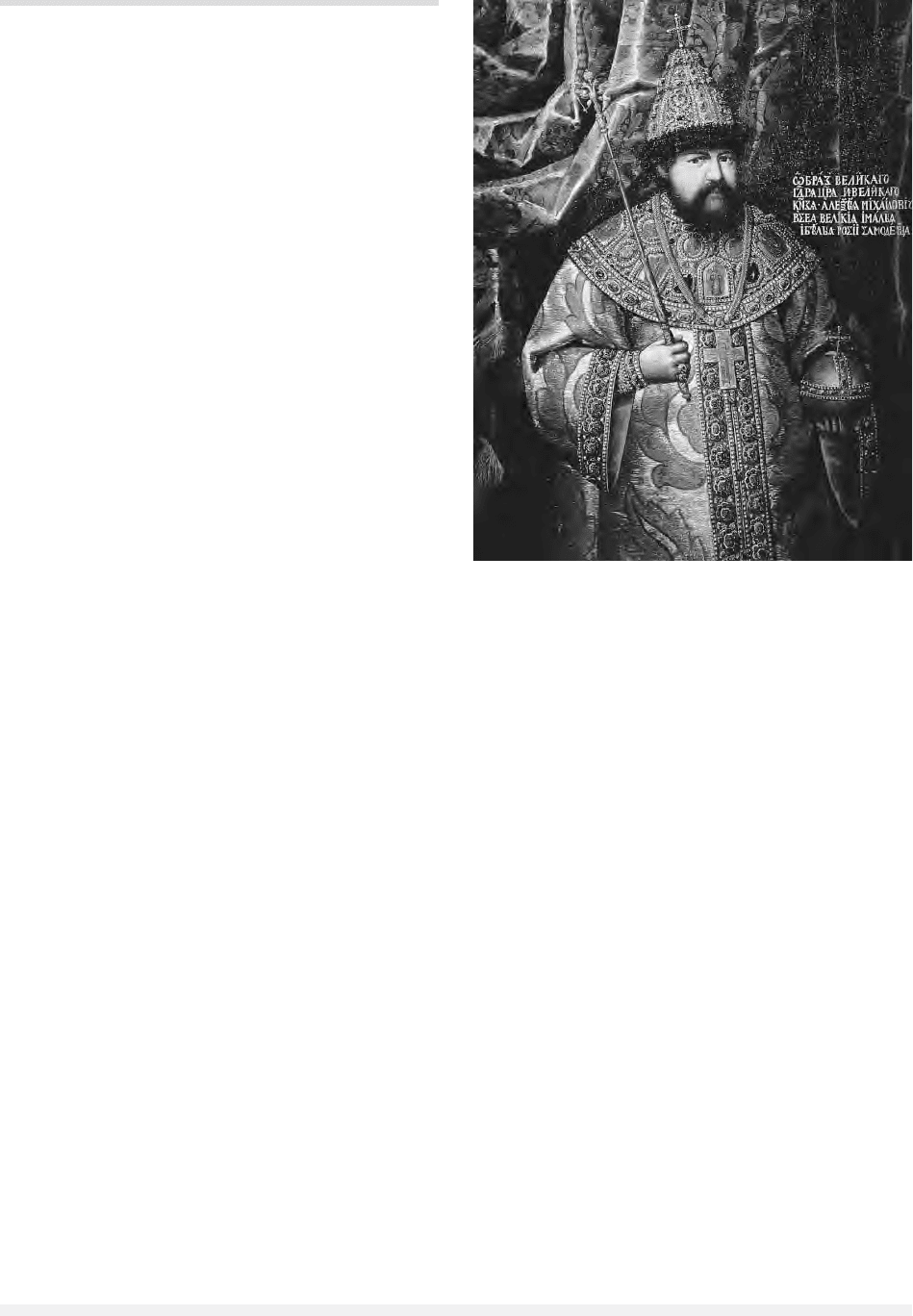

ALEXEI MIKHAILOVICH

(1629–1676), the second Romanov tsar (r. 1645–1676)

and the most significant figure in Russian history

between the period of anarchy known as the “Time

of Troubles” (smutnoye vremya) and the accession

of his son, Peter I (the Great).

The reign of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich was no-

table for a codification of Russian law that was to

remain the standard until the nineteenth century,

for the acquisition of Kiev and eastern Ukraine from

Poland-Lithuania, and for church reforms. Alexei

also laid the foundations for the modernization of

the army, introduced elements of Western culture

to the court, and, despite a series of wars and

rebellions, strengthened the autocracy and the au-

thority of central government. He anticipated di-

rections his son Peter would take: He substituted

ability and service for hereditary and precedent as

qualifications for appointments and promotions;

engaged Dutch shipwrights to lay down the first

Russian flotilla (for service in the Caspian); and in-

troduced other forms of Western technology and

engaged many military and civil experts from the

West. Not all of his initiatives succeeded, however.

His attempt to seize the Baltic port of Riga was

thwarted by the Swedes, and his flotilla based at

Astrakhan was burned by rebels. Nevertheless Rus-

sia emerged as a great European power in his reign.

REPUTATION AND ITS ORIGINS

Despite his importance, Alexei’s reputation stands

low in the estimation of historians. Earlier works,

by Slavophiles, religious traditionalists, and those

nostalgic for the old Russian values, depict him as

pious, caring, ceremonious, occasionally angry, yet

essentially spiritual, distracted from politics and

policy-making. Vladimir Soloviev concluded that

he was indecisive, afraid of confrontation, even sly.

Vasily Klyuchevsky, Sergei Platonov, and most later

historians, Russian and Western, also conclude that

he was weak, dominated by favorites. This erro-

neous view derives from several sources: from the

Petrine legend created by Peter’s acolytes and suc-

cessors; from his soubriquet tishaysheyshy, the

diplomatic title Serenissimus (Most Serene High-

ness), which was taken out of context to mean

“quietest,” “gentlest,” and, metaphorically, even

“most underhanded”; from the fact that the sur-

viving papers from Alexei’s Private Office papers

were not published until the first decades of the

twentieth century (even though registered in the

early eighteenth century by order of Peter himself)

and were ignored by most historians thereafter.

EDUCATION AND FORMATION

Alexei was brought up as a prince and educated as

a future ruler. In 1633 an experienced minister,

Boris Ivanovich Morozov, soon to be promoted to

the highest rank (boyar), and to membership of the

tsar’s Council (duma), was given charge of the boy.

He chose the tsarevich’s tutors, provided an en-

tourage for him of about twenty boys of good fam-

ily who were to wait on and play with him. The

brightest of these, including Artamon Matveyev,

who was to serve him as a minister, were also to

share his lessons. Miniature weapons and a model

ship figured prominently among his toys. Leisure

included tobogganing and fencing, backgammon

and chess.

The tsarevich’s formal lessons began at the age

of five with reading. Writing was introduced at

seven, and music (church cantillation) at eight.

Alexei also memorized prayers, learned Psalms and

ALEXEI MIKHAILOVICH

45

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich holding symbols of Russian state

power. T

HE

A

RT

A

RCHIVE

/R

USSIAN

H

ISTORICAL

M

USEUM

M

OSCOW

/

D

AGLI

O

RTI

the Acts of the Apostles, and read Bible stories

(chiefly Old Testament). Exemplary models were

commended to him: the learned St. Abraham, the

Patriotic St. Sergius, St. Alexis, who was credited

with bringing stability to the Russian land, and the

young Tsar Ivan IV (the Terrible), conqueror of the

Tatar khanates of Kazan, Astrakhan, and Siberia.

At nine his education became more secular and

practical, as his tutors were seconded from gov-

ernment offices rather than the clergy. Morozov

himself could explain the governmental machine,

finance, and elements of statecraft. Books on math-

ematics, hydraulics, gunnery, foreign affairs, cos-

mography, and geography were borrowed from

government departments. From the age of ten,

Alexei was an unseen witness of the reception of

ambassadors from east and west. At thirteen he

made his first public appearance, sitting on an ivory

throne beside his father at a formal reception; and

thereafter he played a very visible role. This famil-

iarized him with some of his future duties; it also

reinforced his right to rule. The Romanov dynasty

was new. Alexei would be the first to succeed.

Hence the urgency, when his ailing father died in

July 1645, with which oaths of loyalty were ex-

tracted from every courtier, bureaucrat, and sol-

dier. Even so, the reign was to be difficult.

FIRST YEARS AS TSAR

Morozov headed the new government, taking per-

sonal charge of key departments; the coronation

was fixed for November 1645 (late September O.S.),

and a new program was drawn up, including army

modernization and financial, administrative, and

legal reform. The young tsar’s chief interest, how-

ever, was church reform. There were three reasons

for giving this priority:

1. In Russia, as in the later Roman Empire, church

and state were mutually supportive. The

church acted as the ideological arm of the state,

proclaimed its orders, helped administer rural

areas, and provided prisons, welfare services,

and resources when the state called for them.

2. Since Russia was the richest, most powerful

state in the Orthodox communion, large Or-

thodox populations in neighboring Poland,

which was Catholic, looked to it for support,

and many churchmen in the Ottoman sphere,

including the Balkans, came to Moscow for fi-

nancial support and were therefore receptive to

Moscow’s political influence. This gave the

church some clout in foreign affairs. However,

since Russian liturgical practice differed from

that of other communities, Alexei thought it

important to reform the liturgy to conform to

the best Greek practice. (In doing so he was to

take erroneous advice, but this was discovered

too late.)

3. The rapid exploitation of Siberia had made up

most of the economic damage of the Time of

Troubles, but the legacy of social and moral

dislocation was still evident. A program simi-

lar to that which the Hapsburg rulers had

mounted in Central Europe to combat Protes-

tantism and other forms of dissent had to be

implemented if the increasingly militant

Catholicism of Poland was to be countered, and

pagan practices, still rife in Russia’s country-

side, stamped out.

The Moscow riots of 1648 underscored the ur-

gency. The trigger was a tax on salt that, ironi-

cally, had only recently been rescinded, but as the

movement grew, demands broadened. Alexei con-

fronted the crowd twice, promising redress and

pleading for Morozov’s life. Morozov was spirited

away to the safety of a distant monastery, but the

mob lynched two senior officials, looted many

houses, and started fires. Some of the musketeer

guards (streltsy) sympathized with the crowd, and

seditious rumors spread to the effect that the tsar

was merely a creature of his advisers. Alexei had

to undertake to redress grievances and call an As-

sembly of the Land (zemskii sobor) before order

could be restored (and the Musketeer Corps

purged).

The outcome was a law code (Ulozhenie) in

1649, which updated and consolidated the laws of

Russia, recorded common law practices, and in-

cluded elements of Roman Law and the Lithuanian

Statute as well as Russian secular and canon law.

Alexei was patently acquainted with its content,

and he would subsequently refer to its principles,

such as justice (the administration of the law) be-

ing “equal for all.”

PATRIARCH NIKON AND

THE RUSSIAN CHURCH

In April 1652 when the Russian primate, Patriarch

Joseph, died, Alexei had already decided on his suc-

cessor. He had met Nikon, now in his early fifties

and an impressive six feet, five inches tall, seven

years before. He had since installed him as abbot of

a Moscow monastery in his gift and thereafter met

him regularly. He had subsequently proposed him

ALEXEI MIKHAILOVICH

46

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

to the metropolitan see of Novgorod, the second

most senior position in the Russian church. How-

ever, Nikon insisted on conditions for accepting

nomination as patriarch. His demand that the tsar

obey him in all matters relating to the church’s

spiritual authority was not as unacceptable as

might appear. Nikon had to impose discipline on

laity and clergy alike, and the tsar felt a duty to

give a lead, to demonstrate that patriarch and tsar

were working in symphony. But Nikon’s second

demand was more difficult.

One way to improve observance and confor-

mity was to create new saints and transfer their

remains to Moscow in gripping public ceremonies.

The new saints included two patriarchs who had

suffered during the Polish intervention: Job, who

had been imprisoned by the False Dmitry, and Her-

mogen, who had been starved to death by the Poles

in 1612. But Nikon also insisted that the former

metropolitan Philip, strangled on Tsar Ivan’s or-

ders, be canonized and that Alexei express contri-

tion in public for Ivan’s sin. Though Ivan was

patently unbalanced in his later years, he was a

model for Alexei, who set out to pursue Ivan’s

strategic objectives.

The “Prayer Letter” Alexei eventually gave Nikon

to read aloud over Philip’s grave at Solovka was

cleverly ambivalent. Often interpreted as a sub-

mission by the tsar to the church, it asserts that

the acknowledgement of Ivan’s sin has earned him

forgiveness, and is, in effect, a rehabilitation of

Ivan. Nikon was duly installed as patriarch. The re-

forms went ahead.

WAR WITH POLAND-LITHUANIA

When the war over Ukraine began in 1654, Alexei

joined his troops on campaign, leaving Nikon to act

as regent in Moscow in his absence. The city of

Smolensk was retaken, and Khmelnytsky, leader of

the Ukrainian Cossack insurgents, whom Moscow

had been supplying for some time, made formal

submission to the tsar’s representative. Glittering

success also attended the 1655 campaign. Opera-

tions were unaffected by an outbreak of bubonic

plague in Moscow, with which Nikon coped effi-

ciently. Most of Lithuania, including its capital Vil-

nius, fell to Russian troops that summer. This

opened the road to the Baltic, and in 1656 the army

moved on to besiege the Swedish port of Riga. But

Riga held out, there was a Polish resurgence, and

part of the Ukrainian elite abandoned their alle-

giance to the tsar. The war was to drag on for an-

other decade, bringing chaos to Ukraine and mount-

ing costs to Moscow. It also occasioned the breach

with Nikon.

To consolidate his rule of Ukrainian and Be-

larus territory, formerly under Poland, Alexei ur-

gently needed to fill the vacant metropolitan see

of Kiev. The last incumbent had died in 1657 (the

same year as Khmelnytsky) but Nikon refused to

sanction the appointment, arguing that Kiev came

under the jurisdiction of the superior see of Con-

stantinople. The tsar made his disapproval public.

Nikon relinquished his duties but refused to resign,

and the matter remained unresolved until 1666

when Nikon was impeached by a synod attended

by the patriarchs of Alexandria and Antioch, the

tsar acting as prosecutor. The synod found against

Nikon and deposed him, but endorsed his liturgi-

cal reforms, which were unpopular with Avvakum

and other Old Believers. However, Nikon had been

set up as a scapegoat for the unpopular measures

against Old Belief. Although Alexei failed to per-

suade Avvakum to conform, he retained the re-

bellious archpriest’s respect. The church was to

remain at an uneasy peace for the remainder of the

reign.

Reforms occasioned by the demands of war in-

cluded three significant developments.

1. The formation of the tsar’s Private Office. Staffed

by able young bureaucrats, it kept the tsar

closely and confidentially informed, intervened

at the tsar’s behest in both government and

church affairs, and supervised the conduct of

the war, when necessary overriding generals,

ministers, and provincial governors. Those

who served in the Office often went on to oc-

cupy the highest posts; several entered the

Duma. The Private Office became an effective

instrument for personal, autocratic rule.

2. It hastened military modernization. The tsar reg-

ularly engaged foreign officers to drill Russian

servicemen in the latest Western methods.

Weaponry and artillery were improved and

their production expanded. By the end of the

reign, except for the traditional cavalry (still

useful for steppe warfare), the army had been

transformed. Aside from the crack musketeer

guards, commanded by Artamon Matveyev,

the musketeer corps was sidelined, and “regi-

ments of new formation” became the core of

the army.

3. Though the war provided economic stimulus, es-

pecially to mining, metallurgy, and textiles, it

also occasioned insoluble financial problems.

ALEXEI MIKHAILOVICH

47

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

With expenditure soaring above income, and

being short of specie, Alexei sanctioned the is-

sue of copper coins instead of silver. Ukrainian

servicemen, finding their pay would not buy

them necessities of life, became rebellious; and,

as inflation increased, dismay and anger in-

fected the cities. A crowd from Moscow reached

the tsar at his summer palace at Kolomenskoye.

The rising was ruthlessly suppressed, but in

1663 the copper coinage was withdrawn,

though other financial demands were to be

made of the people.

ECONOMIC POLICY

Alexei was never to solve the fiscal problem, al-

though he did adopt some positive economic poli-

cies. He improved productivity on his own estates;

encouraged peasants to take profitable initiatives;

sponsored trading expeditions to farthest Siberia,

China, and India; protected the profitable trade with

Persia; established a glass factory, encouraged

prospectors, and brought in Western manufactur-

ers as well as experts in military technology; and

in 1667 introduced a new trade statute designed to

protect Russian merchants from foreign competi-

tors and from intrusive officialdom. Yet he also en-

couraged transit trade within Russia, helping

develop a common Russian market.

The year 1667, which saw the condemnation

of Nikon, also saw the conclusion, at Andrusovo,

of the long war with Poland. Under its terms Rus-

sia kept all Ukraine east of the Dnieper River and

temporary control of Kiev (which soon became per-

manent). This was a huge accretion of territory,

providing a launching pad for future expansion

both westward and to the south. The cost had been

heavy, but Poland had suffered more. Broken as a

great power, it ceased to be a threat to Russia. Alexei

had ensured that neither the hereditary nobility nor

the church would impede the free exercise of au-

tocratic, centralizing power.

Both strategic policy and church reform di-

rected Moscow’s attention westward. Alexei be-

came interested in acquiring the crown of Catholic

Poland and his eldest surviving son, Tsarevich

Alexei, was taught Polish and Latin. The boy’s tu-

tor, Simeon Polotsky, who was also the court poet,

had been brought to Moscow with other bearers of

Western learning and culture from occupied Be-

larus and Ukraine. Insulated from the mass of Rus-

sians, their influence was confined to court.

Similarly, foreign servicemen and experts were con-

fined to Moscow’s Foreign Suburb when off duty.

Nevertheless they were the basis of Russia’s West-

ernization; and the tsar chose his second wife, Na-

talia Naryshkina, from the suburb. Their child,

Peter, was to be reviled as the son of Nikon. But as

Wuchter’s portrait of Alexei demonstrates, he was

clearly Peter’s father, and in spirit as well as ge-

netically.

Through his policies of modernization, his

church reforms, his introduction of Ukrainian

learning (and hence elements of Catholic learning),

Alexei had, wittingly and unwittingly, pierced Rus-

sia’s isolationism. But he was not to see all the

fruits of this work. Worn down by three decades

of political and military crises for which as auto-

crat he bore sole responsibility, Alexei died of renal

and heart disease on January 29, 1676.

See also: IVAN IV; LAW CODE OF 1649; MILITARY, IMPER-

IAL ERA; MOROZOV, BORIS IVANONVICH; NIKON, PA-

TRIARCH; PETER I; ROMANOV DYNASTY; RUSSIAN

ORTHODOX CHURCH; THIRTEEN YEARS’ WAR; TIME OF

TROUBLES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Longworth, Philip. (1984). Alexis, Tsar of All the Russias.

New York: Franklin Watts.

Longworth, Philip. (1990). “The Emergence of Abso-

lutism in Russia.” In Absolutism in Seventeenth Cen-

tury Europe, ed. John Miller. London: Macmillan.

Palmer, W. (1871–1876). The Patriarch and the Tsar, 6

vols. London: Trubner.

P

HILIP

L

ONGWORTH

ALEXEI NIKOLAYEVICH

(1904–1918), last of the Romanov dynasty of Rus-

sia.

Alexei Nikolayevich Romanov was the only son

of Tsar Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra and the

youngest member of Russia’s last royal family. The

Romanovs’ elation over the birth of an heir to the

throne quickly turned to worry, when doctors di-

agnosed Alexei with hemophilia, a hereditary dis-

order preventing the proper clotting of blood.

Despite bouts of severe physical pain, Alexei was a

happy and mischievous boy. Nonetheless, the un-

predictable ebbs and flows in his condition dictated

the mood of the tightly knit royal family. When

Alexei was not well, melancholy reigned in the Ro-

manov home.

ALEXEI NIKOLAYEVICH

48

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

After the doctors admitted that they could find

no way to ease the boy’s suffering, Empress

Alexandra turned to a Siberian peasant and self-

styled holy man, Grigory Yefimovich Rasputin.

Rasputin somehow managed to temporarily stop

Alexei’s hemorrhaging, thus gaining the trust of

the tsar’s family. Believing Rasputin to be their

son’s benefactor and clinging to hope for Alexei’s

recovery, Nicholas and Alexandra rejected rumors

of the mysterious peasant’s debauched lifestyle.

Their patronage of Rasputin caused outrage in court

circles and educated society, which contributed to

the declining authority of the monarchy and its

eventual collapse in 1917.

In July 1918, just days before his fourteenth

birthday, Alexei was murdered, along with his par-

ents, four sisters, and several royal servants, by a

Bolshevik firing squad. In 1981, the Russian Or-

thodox Church Abroad canonized Alexei, along

with the rest of the royal family, for accepting

ALEXEI NIKOLAYEVICH

49

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Tsarevich Alexei Nikolayevich, age 11, and his mother, Tsarina Alexandra Fedorovna. © H

ULTON

-D

EUTSCH

C

OLLECTION

/CORBIS

death with faith in God and humility. The Moscow

Patriarchate canonized the royal family in 2000.

See also: ALEXANDRA FEDOROVNA; NICHOLAS II; RASPUTIN,

GRIGORY YEFIMOVICH; ROMANOVA, ANASTASIA NIKO-

LAYEVNA; ROMANOV DYNASTY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Massie, Robert K. (2000). Nicholas and Alexandra. New

York: Ballantine Books.

N

ICHOLAS

G

ANSON

ALEXEI PETROVICH

(1690–1718), tsarevich, son of Emperor Peter I of

Russia and his first wife Yevdokia Lopukhina.

Peter raised Alexei as his heir, making him

study a modern curriculum with foreign tutors

and taking him to visit battlefields and naval dis-

plays to teach him to “love everything that con-

tributes to the glory and honor of the fatherland.”

When Alexei was in his twenties, Peter entrusted

him with important duties on the home front in

the war against Sweden. Peter’s correspondence re-

veals little affection for Alexei, who in turn felt in-

timidated by his demanding and unconciliatory

father (Peter had banished Alexei’s mother in 1699).

Alexei was intelligent, devout, often sick, and in-

different to military affairs. In 1712 Peter married

him off to the German princess Charlotte of Wolf-

fenbüttel, whom he quickly abandoned for a peas-

ant mistress. After the birth of Alexei’s son Peter

(the future Peter II) in 1715, Peter accused Alexei

of neglecting the common good and threatened to

disinherit him: “Better a worthy stranger [on the

throne] than my own unworthy son.” Under in-

creasing pressure, in 1716 Alexei fled and took

refuge with the Habsburg emperor, but in 1718 Pe-

ter lured him back home with the promise of a par-

don, then disinherited him and demanded that he

reveal all his “accomplices” in a plot to assassinate

his father and seize the throne. Evidence emerged

that Alexei hated Peter’s cherished projects and that

some Russians from elite circles viewed him as an

alternative. Tried by a special tribunal, Alexei con-

fessed to treason under torture and was condemned

to death, dying two days later following further

torture. His fate and the witch hunt unleashed by

his trial have disturbed even ardent admirers of Pe-

ter, who was willing to sacrifice his son for rea-

sons of state. Soviet historians dismissed Alexei as

a traitor, but he has been viewed more sympa-

thetically since the 1990s.

See also: PETER I; PETER II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bushkovitch, Paul. (2001). Peter the Great: The Struggle

for Power, 1671–1725. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Hughes, Lindsey. (1998). Russia in the Age of Peter the

Great. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

L

INDSEY

H

UGHES

ALEXEYEV, MIKHAIL VASILIEVICH

(1857–1918), Imperial Russian general staff offi-

cer, commander, Stavka chief of staff and White

Army leader.

General-Adjutant Mikhail Alexeyev was born

in Vyazma, the son of a noncommissioned officer

who had fought at Sevastopol in the Crimean War,

then attained officer rank. Alexeyev completed the

Moscow Junker School (1876) and the Nicholas

Academy of the General Staff (1890). He taught at

the latter between 1898 and the Russo-Japanese

War, in which he served at Sandepu and Mukden

as chief of staff for the Third Manchurian Army.

A believer in limited monarchy, Alexeyev rose in

1908 to become acting quartermaster general of the

General Staff, then served from 1908 to 1912 as

chief of staff of the Kiev Military District. Until

1911, Alexeyev continued to advise War Minister

Vladimir Aleksandrovich Sukhomlinov on war

planning. Alexeyev’s General Plan of Actions sub-

sequently became a precursor for Mobilization

Schedule 19A, the foundation for Russia’s entry

into World War I. Alexeyev began the war as chief

of staff of the Southwestern Front, then com-

manded the Northwestern Front in 1915 during its

successful but costly withdrawal from the Polish

salient.

As Stavka chief of staff for Tsar Nicholas II af-

ter August 1915, Alekseyev functioned as de facto

supreme commander, but was tainted in 1916 by

the ill-conceived Naroch operation and by failure

to support the more successful Brusilov Offensive.

While maintaining contact with the liberal opposi-

tion, he left Stavka in December 1916 for reasons

of health, then returned in March to June 1917 as

ALEXEI PETROVICH

50

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

supreme commander. An ardent anti-Bolshevik be-

tween the two Russian revolutions of 1917, he

fought against the disintegration of the army, even

agreeing to serve temporarily as the army’s com-

mander-in-chief after the Kornilov Affair of Sep-

tember 1917. Following the Bolshevik coup of

November 1917, Alexeyev and Lavr Georgievich

Kornilov became the military nucleus around which

a White counterrevolutionary movement in the

Don and Kuban organized the Volunteer Army.

Alexeyev’s death in October 1918 at Yekaterinodar

deprived the Whites of perhaps their most talented

commander and planner. He left the legacy of a

keen military professional who consistently ren-

dered impressive service as commander and staff

officer under extraordinarily challenging military

and political circumstances.

See also: KORNILOV AFFAIR; NICHOLAS II; STAVKA; WHITE

ARMY; WORLD WAR I

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Wildman, Allan K. (1980, 1987). The End of the Russian

Imperial Army. 2 vols. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Uni-

versity Press.

O

LEG

R. A

IRAPETOV

ALIYEV, HEIDAR

(b. 1923), Soviet Azerbaijani statesman, president

of Azerbaijan (1993– ).

Heidar Alirza Oglu Aliyev was born in Nak-

hichevan, Azerbaijani SSR. Aliyev studied architec-

ture and history in Baku. In 1944 he joined the

KGB of Soviet Azerbaijan and became its director in

1967. In 1969 Aliyev became first secretary of the

Communist Party (thus effective leader) of Soviet

Azerbaijan. In 1982 he was invited to Moscow as

a full member of the Communist Party of the So-

viet Union (CPSU) Politburo and first deputy chair-

man of the USSR Council of Ministers. He also

served as a member of the Supreme Soviet of the

USSR for twenty years.

Following Mikhail Gorbachev’s accession to

power, Aliyev was forced to resign from his posi-

tions in the Party in 1986 and in the government

in 1987. Aliyev resigned from the CPSU in July

1990 citing, among other reasons, his objections to

the use of the Soviet army units against demon-

strators in Baku earlier that year. He returned to

Nakhichevan, where he relaunched his career as

the chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Nak-

hichevan and deputy chairman of the Azerbaijani

Supreme Soviet. In 1993 he was asked by the em-

battled President Abulfaz Elchibey of independent

Azerbaijan to return to Baku. By October 1993

Aliyev was elected president of Azerbaijan. He was

reelected in 1998.

Aliyev’s main priority as leader of independent

Azerbaijan was to secure domestic stability and ef-

fective control and exploitation of the country’s

hydrocarbon resources. Aliyev was able to neu-

tralize unruly elements that threatened internal

peace, as well as others who could challenge him

politically, while pursuing a policy of selective po-

litical and economic liberalization.

In foreign affairs Aliyev adopted a supple and

pragmatic approach. He moderated his predeces-

sor’s excessively pro-Turkish, anti-Russian, and

anti-Iranian policies. Aliyev used the country’s hy-

drocarbon resources to increase Azerbaijan’s inter-

national stature and, working closely with Georgia,

secured the West’s political support to balance Rus-

sia’s influence.

Aliyev’s initial policy of continuing military

operations in the Nagorno-Karabakh war caused

further territorial losses to Armenian forces as well

as a new wave of internally displaced persons. In

1994 he agreed to a cease-fire. Aliyev has supported

the Organization for Security and Cooperation in

Europe’s mediation efforts for a permanent solu-

tion to the problem of Nagorno-Karabakh as well

as direct negotiations.

His administration continues to be plagued by

charges of authoritarianism, widespread corrup-

tion, and tampering with elections. Eight years into

his administration, Aliyev’s main challenges—the

problems of Karabakh, of succession, and of se-

curing new major routes for the export of Caspian

hydrocarbon resources—remain largely unre-

solved.

See also: ARMENIA AND ARMENIANS; AZERBAIJAN AND

AZERIS; NATIONALITIES POLICIES, SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Curtis, Glenn E. (1994). Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Geor-

gia. Washington, DC: Library of Congress.

Herzig, Edmond. (1999). The New Caucasus: Armenia,

Azerbaijan, and Georgia. London: Royal Institute of

International Affairs.

ALIYEV, HEIDAR

51

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Swietochowski, Tadeusz. (1995). Russia and Azerbaijan:

A Borderland in Transition. New York: Columbia Uni-

versity Press.

G

ERARD

J. L

IBARIDIAN

ALLIED INTERVENTION

The Russian Revolution of 1917, occurring in the

third year of World War I, initially inspired great

hopes in the countries engaged in the brutal strug-

gle against the Central Powers that was exacting

so terrible a carnage and so enormous a financial

drain. The prospect of a new ally, the United States,

seemed bright, since a war without the Romanov

autocracy as an ally could now be claimed to be

truly one of democracy against the old order of Eu-

rope, of which Russia had been one of the bastions.

Unfortunately, Russia was already severely weak-

ened by the war, both on the battlefield and on the

home front. It was left to the United States to pro-

vide direct aid and a moral presence, but time was

running out, and opposition to the war, with its

huge human sacrifices and economic burdens, was

a persistent trend in the new “democratic” Russia.

The inability of the Provisional Government, headed

by Alexander Kerensky, to deal with the situation

led to a victory of the left wing of the revolution

in the form of a Bolshevik seizure of power in Oc-

tober 1917.

This created a dilemma for the Allies, because

the Bolsheviks were largely committed to ending

the war. If the new Soviet government withdrew

from the war, considerable German military forces

would be shifted from the Eastern Front to the

Western Front in 1918, thus nullifying the mount-

ing American presence there. Opinion was sharply

divided on a course of action. Some Allied agents

in Russia believed that Bolshevik leaders could be

persuaded to delay a peace or even to continue a

military effort in return for desperately needed aid.

Others advocated direct military intervention to

maintain an Eastern Front, especially because of ev-

idence that some units of the old Russian army re-

mained intact and committed to continuing the

war. American and British representatives in Rus-

sia, such as Raymond Robins and Robert Bruce

Lockhart, campaigned for the former course, while

influential political leaders urged direct military in-

tervention, some maintaining that an American

force of 100,000, could not only maintain a viable

Eastern Front but also destroy the “communist

threat.”

The crisis came in March 1918 with the Soviet

government’s negotiation of terms for a peace with

Germany at Brest-Litovsk. Since there had been no

forthright pledge of assistance, Vladimir Lenin felt

that ratification of the treaty was necessary, but

about the same time, due to deteriorating condi-

tions in the major ports that contained large

amounts of Allied supplies for Russia, detachments

of marines from Allied warships in the harbors

landed to safeguard personnel and reestablish or-

der in the old port of Archangel on the White Sea,

in the new one of Murmansk in March 1918, and

at Vladivostok on the Pacific in April. Doing any-

thing more at the time was precluded by the con-

centration of available men and supplies on the

Western Front to stem a surprisingly successful

German offensive. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk gave

Germany access to a large part of the Russian Em-

pire and to valuable military supplies, much of Al-

lied origin. Moreover, a large number of liberated

German and Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war

were able to return to combat in the West or con-

trol large areas of Russia, such as Siberia.

With the German offensive in the West stopped,

but the Russian situation continuing to deteriorate,

the Allies considered a more substantial military in-

tervention. President Woodrow Wilson was reluc-

tant to interfere in another country’s affairs,

especially because it might result in dividing the old

Russian Empire and its resources among the other

Allies. But, in the interests of Allied harmony (and

their commitment to a future League of Nations),

he agreed in July 1918 to send American forces to

northern Russia and Siberia. About 4,600 Ameri-

can troops, dubbed the Polar Bears, arrived in

Murmansk and Archangel in August 1918, ac-

companied by a slightly larger British force and

smaller Allied units (a total of about 12,000). The

expeditionary force was under British command,

much resented by the Americans throughout the

campaign. Its mission was to protect the supplies

in the ports, but also to secure lines of communi-

cation by water and rail into the interior. The lat-

ter resulted in a number of skirmishes with Red

Army units during the winter of 1918 to 1919 and

several casualties (though the influenza epidemic

would claim many more). This intervention on

Russian territory was supported by much of the

local population, which was represented by a non-

Bolshevik but socialist soviet at Archangel, thus

complicating the question of what kind of Russia

the Allied forces were fighting for. The end of the

war challenged the legitimacy of an Allied inter-

ALLIED INTERVENTION

52

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY