Encyclopedia of Russian History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Marshal Sergei Akhromeyev played a key role

in ending the Cold War and the negotiation of key

arms control agreements: the INF (Inter-Mediate

Range Nuclear Forces) Treaty (1987) and the CFE

(Conventional Forces in Europe) Treaty (1990)

between NATO and Warsaw Treaty Organization

member states. He also oversaw the Soviet military

withdrawal from Afghanistan. According to Ad-

miral William Crowe, his American counterpart,

“He was a communist, a patriot and a soldier.” Ded-

icated to the rejuvenation of the Soviet system,

Akhromeyev found that perestroika had unleashed

deep conflicts within the USSR and undermined the

system’s legitimacy. After playing a part in the un-

successful coup of August 1991, he committed sui-

cide in his Kremlin office.

Born in 1923, Akhromeyev belonged to that

cohort upon whom the burden of World War II fell

most heavily. The war shaped both his career as a

professional soldier and his understanding of the

external threat to the Soviet regime. He enrolled in

a naval school in Leningrad in 1940 and was in

that city when the German invasion began. He

served as an officer of naval infantry in 1942 at

Stalingrad and fought with the Red Army from the

Volga to Berlin. Akhromeyev advanced during the

war to battalion command and joined the Com-

munist Party in 1943.

In the postwar years Akhromeyev rose to

prominence in the Soviet Armed Forces and Gen-

eral Staff. In 1952 he graduated from the Military

Academy of the Armor Forces. In 1967 he gradu-

ated from the Military Academy of the General

Staff. Thereafter, he held senior staff positions and

served as head of a main directorate of the General

Staff from 1974 to 1977 and then as first deputy

chief of the General Staff from 1979 to 1984. As

Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov’s deputy, Akhromeyev

sought to recast the Soviet Armed Forces to meet

the challenge of the revolution in military affairs,

which involved the application of automated troop

control, electronic warfare, and precision strikes to

modern combined arms combat.

See also: AFGHANISTAN, RELATIONS WITH; ARMS CON-

TROL; AUGUST 1991 PUTSCH; COLD WAR; MILITARY,

SOVIET AND POST-SOVIET

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Herspring, Dale. (1990). The Soviet High Command,

1964–1989: Politics and Personalities. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Kipp, Jacob W., Bruce W. Menning, David M. Glantz,

and Graham H. Turbiville, Jr. “Marshal Akhromeev’s

Post-INF World” Journal of Soviet Military Studies

1(2):167–187.

Odom, William E. (1998). The Collapse of the Soviet Mil-

itary. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press

Zisk, Kimberly Marten. (1993). Engaging the Enemy: Or-

ganization Theory and Soviet Military Innovation,

1955–1991. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

J

ACOB

W. K

IPP

AKHUNDOV, MIRZA FATH ALI

(1812–1878), celebrated Azerbaijani author, play-

wright, philosopher, and founder of modern liter-

ary criticism, who acquired fame primarily as the

writer of European-inspired plays in the Azeri-

Turkish language.

Akhundov was born in Shaki (Nukha), Azer-

baijan, and initially was tutored for the Islamic

clergy by his uncle Haji Alaksar. However, as a

young man he gained an appreciation for the arts,

especially literature. An encounter with famed

Azerbaijani lyricist and philosopher Mirza Shafi

Vazeh in 1832 is said to have profoundly influ-

enced his career as a writer. In 1834, he relocated

to Tbilisi, Georgia, where he worked as a transla-

tor in the Chancellery of the Viceroy of the Cau-

casus. Here he was further influenced in his social

and political views through his acquaintance with

exiled Russian intellectuals, including Alexander

Bestuzhev-Marlinsky.

Akhundov’s first published work was entitled

“Oriental Poem” (1837), inspired by the death

of famous Russian poet Alexander Sergeyevich

Pushkin. However, his first significant literary ac-

tivity emerged in the 1850s, through a series of

comedies that satirized the flaws and absurdities of

contemporary society, largely born of ignorance

and superstition. These comedies were highly

praised in international literary circles, and Akhun-

dov was affectionately dubbed “The Tatar Moliere.”

In 1859 Akhundov published his famous novel

The Deceived Stars, thus laying the groundwork for

realistic prose, providing models for a new genre

in Azeri and Iranian literature.

In his later work, such as Three Letters of the In-

dian Prince Kamal al Dovleh to His Friend, Iranian

Prince Jalal al Dovleh, Akhundov’s writing evolved

AKHUNDOV, MIRZA FATH ALI

23

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

from benign satire to acerbic social commentary. At

this stage, he demonstrated the typical leanings of

the nineteenth-century intelligentsia toward the En-

lightenment movement and its associated principles

of education, political reform, and secularism.

Akhundov’s secular views, a by-product of his ag-

nostic beliefs, stemmed from disillusionment with

his earlier studies in theology. He perceived Islam’s

hold on all facets of society as an obstruction to

learning. Although assaulting traditional institu-

tions was seemingly his stock in trade, his biting

satires were usually leavened with a message of op-

timism for the future. According to Tadeusz Swi-

etochowski, noted scholar of Russian history,

Akhundov believed that “the purpose of dramatic

art was to improve peoples’ morals” and that the

“theater was the appropriate vehicle for conveying

the message to a largely illiterate public.”

See also: AZERBAIJAN AND AZERIS; CAUCASUS; ENLIGHT-

ENMENT, IMPACT OF

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Azeri Literature. (2003). “Mirza Faith Ali Akhundov.”

<http://literature.azner.org/literature/makhundov/

makhundov.en.htm>.

Swietockhowski, Tadeusz. (1995). Russia and Azerbaijan:

A Borderland in Transition. New York: Columbia Uni-

versity Press.

Swietockhowski, Tadeusz, and Collins, Brian. (1999).

Historical Dictionary of Azerbaijan. New York: Scare-

crow Press.

G

REGORY

T

WYMAN

AKKERMAN, CONVENTION OF

By the mid-1820s, the Balkans and the Black Sea

basin festered with unresolved problems and dif-

ferences, including recurring cycles both of popu-

lar insurrection and Turkish repression and of

various Russian claims and Turkish counterclaims.

Most blatantly, in violation of the Treaty of

Bucharest (1812), Turkish troops had occupied the

Danubian principalities, and the Porte had en-

croached on Serbian territorial possessions and au-

tonomy. On March 17, 1826, Tsar Nicholas I issued

an ultimatum demanding Turkish adherence to

the Bucharest agreement, withdrawal of Turkish

troops from Wallachia and Moldavia, and entry

via plenipotentiaries into substantive negotiations.

An overextended and weakened Sultan Mahmud

agreed to negotiations beginning in July 1826 at

Akkerman on the Dniester estuary.

On October 7, 1826, the two sides agreed to

the Akkerman Convention, the terms of which af-

firmed and extended the conditions of the earlier

Bucharest Treaty. Accordingly, Turkey transferred

to Russia several settlements on the Caucasus lit-

toral of the Black Sea and agreed to Russian-ap-

proved boundaries on the Danube. Within eighteen

months, Turkey was to settle claims against it by

Russian subjects, permit Russian commercial ves-

sels free use of Turkish territorial waters, and grant

Russian merchants unhindered trade in Turkish

territory. Within six months, Turkey was to

reestablish autonomy within the Danubian princi-

palities, with assurances that the rulers (hospodars)

would come only from the local aristocracy and

that their replacements would be subject to Russ-

ian approval. Strict limitations were imposed on

Turkish police forces. Similarly, Serbia reverted to

autonomous status within the Ottoman Empire.

Alienated provinces were restored to Serbian ad-

ministration, and all taxes on Serbians were to be

combined into a single levy. In long-term perspec-

tive, the Akkerman Convention strengthened Rus-

sia’s hand in the Balkans, more strongly identified

Russia as the protector of Balkan Slavs, and fur-

ther contributed to Ottoman Turkish decline.

See also: BUCHAREST, TREATY OF; SERBIA, RELATIONS

WITH; TURKEY, RELATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jelavich, Barbara. (1974). St. Petersburg and Moscow:

Tsarist and Soviet Foreign Policy, 1814–1974. Bloom-

ington: Indiana University Press.

Seton-Watson, Hugh. (1967). The Russian Empire

1801–1917. Oxford: At the Clarendon Press.

B

RUCE

W. M

ENNING

AKSAKOV, IVAN SERGEYEVICH

(1823–1886), Slavophile and Panslav ideologue and

journalist.

Son of the famous theater critic Sergei Timo-

feyevich Aksakov, Ivan Aksakov received his early

education at home in the religious, patriotic, and

literary atmosphere of the Aksakov family in

Moscow. He attended the Imperial School of Ju-

AKKERMAN, CONVENTION OF

24

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

risprudence in St. Petersburg, graduating in 1842.

After a nine-year career in government service, Ak-

sakov resigned to devote himself to the study of

Russian popular life and the propagation of his

Slavophile view of it. Troubles with the censorship

plagued his early journalistic ventures: Moskovsky

sbornik (Moscow Miscellany) (1852, 1856) and

Russkaya beseda (Russian Conversation); his news-

paper, Parus (Sail), was shut down in 1859 because

of Aksakov’s outspoken defense of free speech.

In his newspapers Den (Day) and Moskva

(Moscow), Aksakov largely supported the reforms

of the 1860s and 1870s, but his nationalism be-

came increasingly strident, as the historical and

critical publicism of the early Slavophiles gave way,

in the freer atmosphere of the time, to simpler

and more chauvinistic forms of nationalism, often

directed at Poles, Germans, and Jews. In 1875

Aksakov became president of the Moscow Slavic

Benevolent Committee, in which capacity he pressed

passionately for a more aggressive Russian policy

in the Balkans and promoted the creation of Russ-

ian volunteer forces to fight with the Serbs. He was

devastated when the European powers forced Rus-

sia to moderate its Balkan gains in 1878. “Today,”

Aksakov told the Slavic Benevolent Committee, “

we are burying Russian glory, Russian honor, and

Russian conscience.”

In the 1880s Aksakov’s chauvinism became

more virulent. In his final journal, Rus (Old Rus-

sia), he alleged that he had discovered a worldwide

Jewish conspiracy with headquarters in Paris. Ak-

sakov’s increasing xenophobia has embarrassed

Russians (and foreigners) attracted to the more

courageous and generous aspects of his work, but

the enormous crowds at his funeral suggest that

his name was still a potent force among significant

segments of the Russian public at the time of his

death.

See also: AKSAKOV, KONSTANTIN SERGEYEVICH; JOUR-

NALISM; NATIONALISM IN TSARIST EMPIRE; PANSLAV-

ISM; SLAVOPHILES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lukashevich, Stephen. (1965). Ivan Aksakov (1823–1886):

A Study in Russian Thought and Politics. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Riasanovsky, Nicholas. (1952). Russia and the West in the

Teaching of the Slavophiles: A Study of Romantic Ide-

ology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Walicki, Andrzej. (1975). The Slavophile Controversy: His-

tory of a Conservative Utopia in Nineteenth-Century

Russian Thought. Oxford: Clarendon.

A

BBOTT

G

LEASON

AKSAKOV, KONSTANTIN SERGEYEVICH

(1817–1860), Slavophile ideologue and journalist.

Konstantin Aksakov was a member of one of

the most famous literary families in nineteenth-

century Russia. His father was the well-known the-

ater critic and memoirist Sergei Aksakov; his

brother, Ivan Aksakov, was an important publicist

in the 1860s and 1870s.

During his university years in the early 1830s,

Konstantin Aksakov was a member of the Stanke-

vich Circle, along with Mikhail Bakunin and

Vissarion Belinsky. He underwent a period of ap-

prenticeship to Hegel, but, like several other Slavo-

philes, was most influenced by his immediate

family circle, which was the source of the com-

munal values he was to espouse and the dramatic

division in his thought between private and pub-

lic.

Toward the end of the 1830s Aksakov drew

close to Yury Samarin, and both of them fell un-

der the direct influence of Alexei Khomyakov. Ak-

sakov’s Hegelianism proved a passing phase; he

evolved into the most determinedly utopian and

ideologically minded of all the early Slavophiles. A

passionate critic of statist historical interpretations,

Aksakov viewed Russian history as marked by a

unique relationship between the state and what he

called “the land” (zemlya). At one level the division

referred simply to the allegedly limited jurisdiction

of state power in pre-Petrine Russia over Russian

society. At another level “the land” signified the

timeless religious and moral truth of Christianity,

while the state, however necessary for the preser-

vation of “the land,” was external, soulless, and co-

ercive. The Russian peasant’s communal existence

had to be protected from the contagion of politics.

Behind Aksakov’s static “Christian people’s utopia”

lay the romantic hatred of social and political ra-

tionalism, a passion that animated all the early

Slavophiles. Aksakov died suddenly in the Ionian

Islands in the midst of a rare European trip.

See also: AKSAKOV, IVAN SERGEYEVICH; KHOMYAKOV,

ALEXEI STEPANOVICH; SLAVOPHILES

AKSAKOV, KONSTANTIN SERGEYEVICH

25

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Christoff, Peter. (1982). An Introduction to Nineteenth-

Century Russian Slavophilism, Vol. 3: K.S. Aksakov: A

Study in Ideas. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

Riasanovsky, Nicholas. (1952). Russia and the West in the

Teaching of the Slavophiles. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Walicki, Andrzej. (1975). The Slavophile Controversy. Ox-

ford: Clarendon.

A

BBOTT

G

LEASON

ALASH ORDA

Alash Orda is the autonomous Kazakh government

established by the liberal-nationalist Alash party in

December 1917. Alash was the mythical ancestor

of the Kazakhs, and Alash Orda (Horde of Alash)

long served as their traditional battle cry. His name

was adopted by the Kazakh nationalist journal,

Alash, that was published by secularist Kazakh in-

tellectuals for twenty-two issues, from November

26, 1916, to May 25, 1917. Alash Orda then was

taken as the name of a political party founded in

March 1917 by a group of moderate, upper-class

Kazakh nationalists. Among others, they included

Ali Khan Bukeykhanov, Ahmed Baytursun, Mir

Yakub Dulatov, Oldes Omerov, Magzhan Zhum-

abayev, H. Dosmohammedov, Mohammedzhan

Tynyshbayev, and Abdul Hamid Zhuzhdybayev.

Initially, the party’s program resembled that of the

Russian Constitutional-Democrats (Kadets), but

with a strong admixture of Russian Menshevik (So-

cial Democrat) and Socialist-Revolutionary (SR)

ideas. Despite later Soviet charges, it was relatively

progressive on social issues and demanded the cre-

ation of an autonomous Kazakh region. This pro-

gram was propagated in the newspaper Qazaq

(Kazakh), published in Orenburg. The paper had a

circulation of about eight thousand until it was

closed by the Communists in March 1918.

After March 1917, Alash Orda’s leaders domi-

nated Kazakh politics. They convened a Second

All-Kirgiz (Kazakh) Congress in Orenburg from De-

cember 18 through December 26, 1917. On De-

cember 23, this congress proclaimed the autonomy

of the Kazakh steppes under two Alash Orda gov-

ernments. One, centered at the village of Zham-

beitu and encompassing the western region, was

headed by Dosmohammedov. The second, headed

by Ali Khan Bukeykhanov, governed the eastern re-

gion from Semipalatinsk. Both began as strongly

anti-Communist and supported the anti-Soviet

forces that were rallying around the Russian Con-

stituent Assembly (Komuch): the Orenburg Cos-

sacks and the Bashkirs of Zeki Velidi Togan. In

time, however, the harsh minority policies of

Siberia’s White Russian leader, Admiral Alexander

Vasilievich Kolchak, alienated the Kazakh leaders.

Alash Orda’s leaders then sought to achieve their

goals by an alignment with Moscow. Accepting

Mikhail Vasilievich Frunze’s November 1919

promise of amnesty, most Kazakh leaders recognized

Soviet power on December 10, 1919. After further

negotiations, the Kirgiz Revolutionary Committee

(Revkom) formally abolished Alash Orda’s institu-

tional network in March 1920. Many Alash leaders

then joined the Communist Party and worked for

Soviet Kazakhstan, only to perish during Stalin’s

purges of the 1930s. After 1990 the name “Alash”

reappeared, but as the title of a small Kazakh pan-

Turkic and Pan-Islamic party and its journal.

See also: CENTRAL ASIA; KAZAKHSTAN AND KAZAKHS; NA-

TIONALISM IN THE SOVIET UNION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jackson, George, and Devlin, Robert, eds. (1989). Dictio-

nary of the Russian Revolution. Westport, CT: Green-

wood.

Olcott, Martha Brill. (1995). The Kazakhs, 2nd ed. Stan-

ford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Wheeler, Geoffrey. (1964). The Modern History of Soviet

Central Asia. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

D

AVID

R. J

ONES

ALASKA

Alaska is the largest state in the United States, equal

to one-fifth of the country’s continental land mass.

Situated in the extreme northwestern region of

North America, it is separated from Russian Asia

by the Bering Strait (51 miles; 82 kilometers). Com-

monly nicknamed “The Last Frontier” or “Land of

the Midnight Sun,” the state’s official name derives

from an Aleut word meaning “great land” or “that

which the sea breaks against.” Alaska is replete

with high-walled fjords and majestic mountains,

with slow-moving glaciers and still-active volca-

noes. The state is also home to Eskimos and the

Aleut and Athabaskan Indians, as well as about

fourteen thousand Tlingit, Tshimshian, and Haida

ALASH ORDA

26

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

people—comprising about 16 percent of the Alaskan

population. (The term Eskimo is used for Alaskan

natives, while Inuit is used for Eskimos living in

Canada.) Inupiat and Yupik are the two main Es-

kimo groups. While the Inupiat speak Inupiaq and

reside in the north and northwest parts of Alaska,

the Yupik speak Yupik and live in the south and

southwest. Juneau is the state’s capital, but An-

chorage is the largest city.

The first Russians to come to the Alaskan main-

land and the Aleutian Islands were Alexei Chirikov

(a Russian naval captain) and Vitus Bering (a Dane

working for the Russians), who arrived in 1741.

Tsar Peter the Great (1672–1725) encouraged the

explorers, eager to gain the fur trade of Alaska and

the markets of China. Hence, for half a century

thereafter, intrepid frontiersmen and fur traders

(promyshlenniki) ranged from the Kurile Islands to

southeastern Alaska, often exploiting native sea-

faring skills to mine the rich supply of sea otter

and seal pelts for the lucrative China trade. In 1784,

one of these brave adventurers, Grigory Shelekhov

(1747–1795), established the first colony in Alaska,

encouraged by Tsarina Catherine II (the Great)

(1729–1796).

Missionaries soon followed the traders, begin-

ning in 1794, aiming to convert souls to Chris-

tianity. The beneficial role of the Russian missions

in Alaska is only beginning to be fully appreciated.

Undoubtedly, some Russian imperialists used the

missionary enterprise as an instrument in their

own endeavors. However, as recently discovered

documents in the U.S. Library of Congress show,

the selfless work of some Russian Orthodox

priests, such as Metropolitan Innokenty Veni-

aminov (1797–1879), not only promoted harmo-

nious relations between Russians and Alaskans, but

preserved the culture and languages of the Native

Alaskans.

Diplomatic relations between Russia and the

United States, which began in 1808, were relatively

cordial in the early 1800s. They were unhampered

by the Monroe Doctrine, which warned that the

American continent was no territory for future Eu-

ropean colonization. Tsar Alexander I admired the

American republic, and agreed in April 1824 to re-

strict Russia’s claims on the America continent to

Alaska. American statesmen had attempted several

times between 1834 and 1867 to purchase Alaska

from Russia. On March 23, 1867, the expansion-

ALASKA

27

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

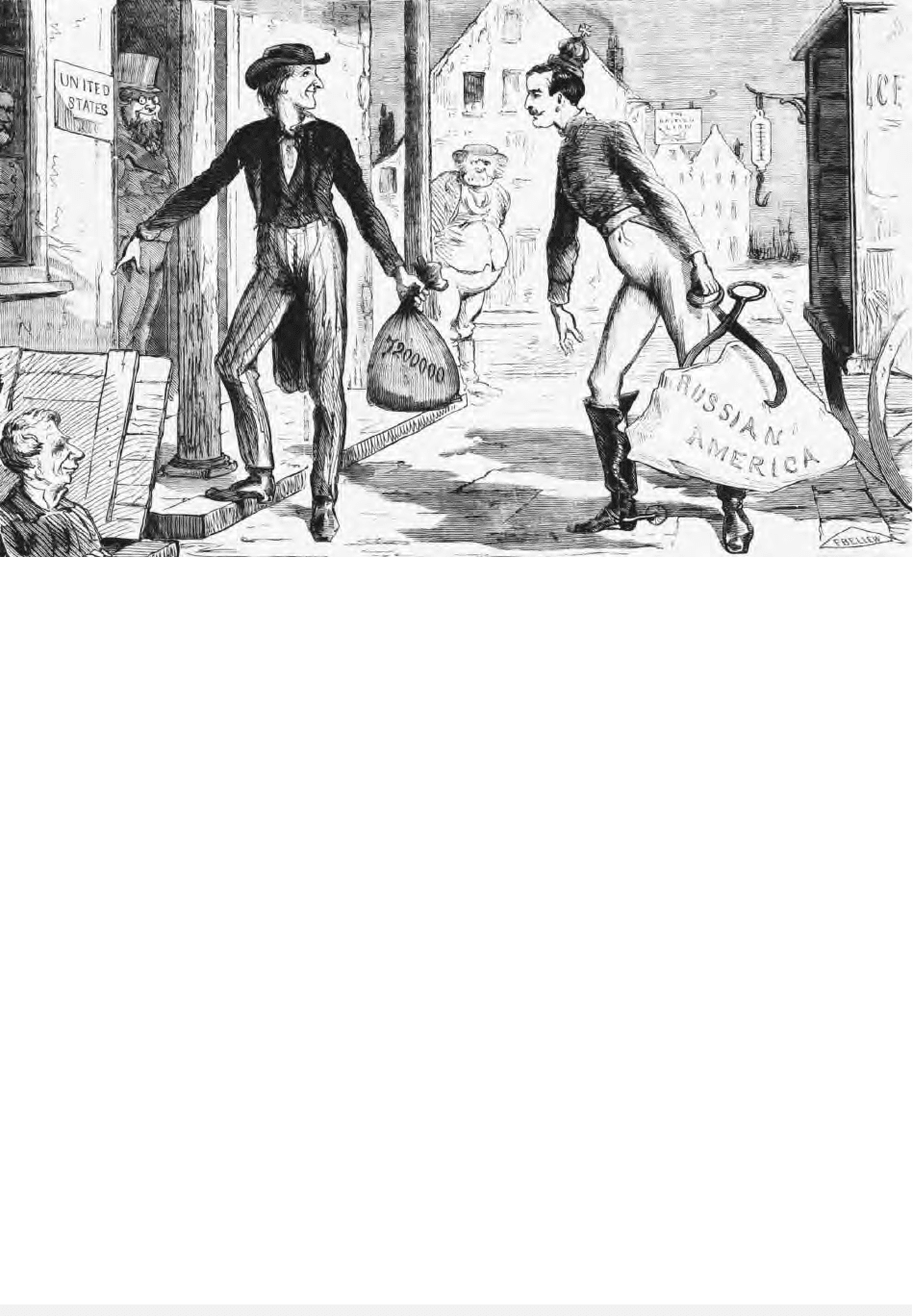

Cartoon ridiculing the U.S. decision to purchase Alaska from Russia. © B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS

ist-minded Secretary of State William H. Seward

met with Russian minister to Washington Baron

Edouard de Stoeckl and agreed on a price of

$7,200,000. This translated into about 2.5 cents

per acre for 586,400 square miles of territory, twice

the size of Texas. Overextended geographically, the

Russians were happy at the time to release the bur-

den. However, the discovery of gold in 1896 and

of the largest oil field in North America (near Prud-

hoe Bay) in 1968 may have caused second thoughts.

See also: BERING, VITUS JONASSEN; DEZHNEV, SEMEN

IVANOVICH; NORTHERN PEOPLES; UNITED STATES, RE-

LATIONS WITH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bolkhovitinov, N. N., and Pierce, Richard A. (1996).

Russian-American Relations and the Sale of Alaska,

1834–1867. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

Hoxie, Frederick E., and Mancall, Peter C. (2001). Amer-

ican Nations: Encounters in Indian Country, 1850 to

the Present. New York: Routledge.

Thomas, David Hurst. (200). Exploring Native North

America. New York: Oxford University Press.

J

OHANNA

G

RANVILLE

ALBANIANS, CAUCASIAN

Albanians are an ancient people of southeastern

Caucasia who originally inhabited the area of the

modern republic of Azerbaijan north of the River

Kur. In the late fourth century they acquired from

Armenia the territory that now comprises the

southern half of the republic. According to the

Greek geographer Strabo (died c. 20

C

.

E

.), the Al-

banians were a federation of twenty-six tribes, each

originally having its own king, but by his time

united under a single ruler. The people’s name for

themselves is unknown, but the Greeks and Ro-

mans called their country Albania. The original

capital of Albania was the city of Cabala or Cabal-

aca, north of the River Kur. In the fifth century,

however, the capital was transferred to Partaw

(now Barda), located south of the river.

According to tradition, the Albanians converted

to Christianity early in the fourth century. It is

more likely, however, that this occurred in the early

fifth century, when St. Mesrob Mashtots, inventor

of the Armenian alphabet, devised one for the Al-

banians. Evidence of this alphabet was lost until

1938, when it was identified in an Armenian man-

uscript. All surviving Albanian literature was writ-

ten in, not translated into, Armenian.

The Persians terminated the Albanian monar-

chy in about 510, after which the country was

ruled by an oligarchy of local princes that was

headed by the Mihranid prince of Gardman. In 624,

the Byzantine emperor Heraclius appointed the

head of the Mihrani family as presiding prince of

Albania. When the country was conquered by the

Arabs in the seventh century and the last of the

Mihranid presiding princes was assassinated in

822, the Albanian polity began to break up. There-

after, the title “king of Albania” was claimed by

one or another dynasty in Armenia or Georgia un-

til well into the Mongol period. The city of Partaw

was destroyed by Rus pirates in 944.

The Albanians had their own church and its

own catholicos, or supreme patriarch, who was

subordinate to the patriarch of Armenia. The Al-

banian church endured until 1830, when it was

suppressed after the Russian conquest. The Alban-

ian ethnic group appears to survive as the Udins,

a people living in northwestern Azerbaijan. Their

Northeast Caucasian language (laced with Armen-

ian) is classified as a member of the Lesguian group.

Some Udins are Muslim; the rest belong to the Ar-

menian Church.

See also: ARMENIA AND ARMENIANS; AZERBAIJAN AND

AZERIS; CAUCASUS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bais, Marco. (2001). Albania Caucasica. Milan: Mimesis.

Daskhurantsi, Moses. (1961).History of the Caucasian Al-

banians. London: Oxford University Press.

Moses of Khoren. (1978). History of the Armenians, tr.

Robert W. Thomson. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Uni-

versity Press.

Toumanoff, Cyrille. (1963). Studies in Christian Caucasian

History. Washington, DC: Georgetown University

Press.

R

OBERT

H. H

EWSEN

ALCOHOLISM

Swedish researcher Magnus Huss first used the

term “alcoholism” in 1849 to describe a variety of

physical symptoms associated with drunkenness.

By the 1860s, Russian medical experts built on

ALBANIANS, CAUCASIAN

28

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Huss’s theories, relying on models of alcoholism

developed in French and German universities to

conduct laboratory studies on the effects of alco-

hol on the body and mind. They adopted the term

“alcoholism” (alkogolizm) as opposed to “drunken-

ness” (pyanstvo) to connote the phenomenon of dis-

ease, and determined that it mainly afflicted the

lower classes.

In 1896, at the urging of the Swiss-born physi-

cian and temperance advocate E. F. Erisman, the

Twelfth International Congress of Physicians in

Moscow established a special division on alcoholism

as a medical problem. Within a year the Kazan

Temperance Society established the first hospital for

alcoholics in Kazan. In 1897, physician and tem-

perance advocate A. M. Korovin founded a private

hospital for alcoholics in Moscow, and in 1898 the

Trusteeships of Popular Temperance opened an out-

patient clinic.

That same year, growing public concern over

alcoholism led to the creation of the Special

Commission on Alcoholism and the Means for

Combating It. Headed by psychiatrist N. M.

Nizhegorodtsev, the ninety-five members of the

commission included physicians, psychiatrists,

temperance advocates, academics, civil servants, a

few clergy, and two government representatives.

Classifying alcoholism as a mental illness, mem-

bers of the commission blamed widespread alco-

holism on the tsarist government, which relied

heavily on liquor revenues and refused to improve

the socioeconomic conditions of the lower classes.

Although they accepted the definition of alco-

holism as a disease, professionals could not agree

on exactly what it was, what caused it, or how to

cure it. These were topics of heated debate, and they

could not be seriously discussed without critical

analysis of the government’s social and economic

policies. Hence, the range of opinions expressed in

professional discourse over alcoholism reflected the

fragmentation of middle-class ideologies near the

end of the imperial period: the abstract civic values

of liberalism and modernization as borrowed from

the West; a powerful and persistent model of cus-

todial statehood; and a pervasive culture of collec-

tivism.

With the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, defin-

itions of alcoholism changed. Seeking Marxist in-

terpretations for most social ills, Soviet health

practitioners defined alcoholism as a petit bourgeois

phenomenon, a holdover from the tsarist past.

Working from the premise that illness could only

be understood in its social context, they determined

that alcoholism was a social disease influenced by

factors such as illiteracy, poverty, and poor living

conditions. In 1926 the director of the State Insti-

tute for Social Hygiene, A. V. Molkov, opened a de-

partment, headed by E. I. Deichman, for the sole

purpose of studying alcoholism as a social disease.

Within four years, however, the department was

closed and the institute disbanded. By placing blame

for alcoholism on social causes, Molkov, Deichman,

and others were, in effect, criticizing the state’s so-

cial policies—a dangerous position in the Stalinist

1930s.

In 1933 Josef Stalin announced that success

was being achieved in the construction of socialism

in the USSR; therefore, it was no longer plagued

by petit bourgeois problems such as alcoholism. For

the next fifty-two years, alcoholism did not offi-

cially exist in the Soviet Union. Consequently, all

public discussion of alcoholism ended until 1985,

when Mikhail S. Gorbachev launched a nationwide

but ill-fated temperance campaign.

See also: ALCOHOL MONOPOLY; VODKA

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Herlihy, Patricia. (2002). The Alcoholic Empire: Vodka and

Politics in Late Imperial Russia. Oxford: Oxford Uni-

versity Press.

Segal, Boris. (1987). Russian Drinking: Use and Abuse of

Alcohol in Prerevolutionary Russia. New Brunswick,

NJ: Publications Division, Rutgers Center of Alcohol

Studies.

Segal, Boris. (1990). The Drunken Society: Alcohol Abuse

and Alcoholism in the Soviet Union, a Comparative

Study. New York: Hippocrene Books.

White, Stephan. (1996). Russia Goes Dry: Alcohol, State,

and Society. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

K

ATE

T

RANSCHEL

ALCOHOL MONOPOLY

Ever since the last quarter of the fifteenth century,

Moscovite princes have exercised control over the

production and sale of vodka. In 1553 Ivan IV (the

Terrible) rewarded some of his administrative elite

(oprichnina) for loyal service with the concession of

owning kabaks or taverns. Even so, these tavern

owners had to pay a fee for such concessions. Un-

der Boris Godunov (1598–1605), the state exerted

ALCOHOL MONOPOLY

29

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

greater control over vodka, a monopoly that was

codified in the 1649 Ulozhenie (code of laws).

Disputes over the succession to the throne at

the end of the seventeenth century loosened state

control over vodka, but Peter I (the Great, r.

1682–1725) reasserted strict control over the state

monopoly. Catherine II (the Great, r. 1762–1796)

allowed the gentry to sell vodka to the state. Since

the state did not have sufficient administrators to

collect revenue from sales, merchants were allowed

to purchase concessions that entitled them to a mo-

nopoly of vodka sales in a given area for a speci-

fied period of time. For this concession, merchants

paid the state a fixed amount that was based on

their anticipated sales. These tax-farmers (otkup-

shchiki) assured the state of steady revenue. The

percentage of total revenue derived from vodka

sales increased from 11 percent in 1724 to 30 per

cent in 1795. Between 1798 and 1825, Tsars Paul

I and Alexander I attempted to restore a state

monopoly, but gentry and merchants, who prof-

ited from the tax-farming system, resisted their at-

tempts.

Under the tax-farming system, prices for vodka

could be set high and the quality of the product

was sometimes questionable. Complaining of adul-

teration and price gouging, some people in the late

1850s boycotted buying vodka and sacked distil-

leries. As part of the great reforms that accompa-

nied the emancipation of the serfs, the tax-farming

system was abolished in 1863, to be replaced by

an excise system. By the late 1890s, it was esti-

mated that about one-third of the excise taxes never

reached the state treasury due to fraud.

Alexander III called for the establishment of a

state vodka monopoly (vinnaia monopoliia) in or-

der to curb drunkenness. In 1893 his minister of

finances, Sergei Witte, presented to the State Coun-

cil a proposal for the establishment of the state

vodka monopoly. He argued that if the state be-

came the sole purchaser and seller of all spirits pro-

duced for the internal market, it could regulate the

quality of vodka, as well as limit sales so that peo-

ple would learn to drink in a regular but moderate

fashion. Witte insisted that the monopoly was an

attempt to reform the drinking habits of people and

not to increase revenue. The result, however, was

that the sale of vodka became the single greatest

source of state revenue and also one of the largest

industries in Russia. By 1902, when the state mo-

nopoly had taken hold, the state garnered 341 mil-

lion rubles; by 1911, the sum reached 594 million.

By 1914, vodka revenue comprised one-third of the

state’s income.

Established in 1894, the monopoly took effect

in the eastern provinces of Orenburg, Perm, Samara,

and Ufa in 1896. By July 1896, it was introduced

in the southwest, to the provinces of Bessarabia,

Volynia, Podolia, Kherson, Kiev, Chernigov, Poltava,

Tavrida, and Ekaterinoslav. Seven provinces in Be-

larus and Lithuania had the monopoly by 1897,

followed by ten provinces in the Kingdom of Poland

and in St. Petersburg, spreading to cover all of Eu-

ropean Russia and western Siberia by 1902 and a

large part of eastern Siberia by 1904. The goal was

to close down the taverns and restrict the sale of

alcoholic beverages to state liquor stores. Restau-

rants would be allowed to serve alcoholic bever-

ages, but state employees in government shops

would handle most of the trade. The introduction

of the monopoly caused a great deal of financial

loss for tavern owners, many of whom were Jews.

Because the state vodka was inexpensive and of uni-

formly pure quality, sales soared. Bootleggers, of-

ten women, bought vodka from state stores and

resold it when the stores were closed.

In 1895 the state created a temperance society,

the Guardianship of Public Sobriety (Popechitel’stvo

o narodnoi trezvosti), in part to demonstrate its in-

terest in encouraging moderation in the consump-

tion of alcohol. Composed primarily of government

officials, with dignitaries as honorary members, the

Guardianship received a small percentage of the

vodka revenues from the state; these funds were

intended for use in promoting moderation in drink.

Most of the limited sums were used to produce en-

tertainments, thus founding popular theater in

Russia. Only a small amount was used for clinics

to treat alcoholics. Private temperance societies

harshly criticized the Guardianship for promoting

moderation rather than strict abstinence, accusing

it of hypocrisy and futility.

With the mobilization of troops in August

1914, Nicholas II declared a prohibition on the con-

sumption of vodka for the duration of the war. At

first alcoholism was reduced, but peasants soon be-

gan to produce moonshine (samogon) on a massive

scale. This moonshine, together with the lethal use

of alcoholic substitutes, took its toll. The use of

scarce grain for profitable moonshine also exacer-

bated food shortages in the cities. In St. Petersburg,

food riots contributed to the abdication of Nicholas

in February 1917.

ALCOHOL MONOPOLY

30

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The new Bolshevik regime was a strict adher-

ent to prohibition until 1924, when prohibition

was relaxed. A full state monopoly of vodka was

reinstated in August 1925, largely for fiscal rea-

sons. While Stalin officially discouraged drunken-

ness, in 1930 he gave orders to maximize vodka

production in the middle of his First Five-Year Plan

for rapid industrialization.

The Soviet state maintained a monopoly on

vodka. As soon as Mikhail Gorbachev became gen-

eral secretary of the Communist Party in 1985, he

began a major drive to eliminate alcoholism, pri-

marily by limiting the hours and venues for the

sale of vodka. This aggressive campaign con-

tributed to Gorbachev’s unpopularity. After he

launched his anti-alcohol drive, the Soviet govern-

ment annually lost between 8 and 11 billion rubles

(equivalent to 13 to 17 billion U.S. dollars, at the

1990 exchange rate) in liquor tax revenue. After

Gorbachev’s fall and the dissolution of the Soviet

Union, the state vodka monopoly was abolished in

May 1992.

Boris Yeltsin attempted to reinstate the mo-

nopoly in June 1993, but by that time floods of

cheap vodka had been imported and many domes-

tic factories had gone out of business. Although

President Vladimir Putin issued an order in Febru-

ary 1996 acknowledging that Yeltsin’s attempt to

reestablish the vodka monopoly in 1993 had failed,

he has also tried to control and expand domestic

production and sales of vodka. The tax code of Jan-

uary 1, 1999 imposed only a 5 percent excise tax

on vodka in order to stimulate domestic consump-

tion. By buying large numbers of shares in vodka

distilleries, controlling their management, and at-

tacking criminal elements in the business, Putin has

attempted to reestablish state control over vodka.

See also: ALCOHOLISM; TAXES; VODKA; WITTE, SERGEI

YULIEVICH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Christian, David. (1990). “Living Water”: Vodka and Russ-

ian Society on the Eve of Emancipation. Oxford: Claren-

don Press.

Herlihy, Patricia. (2002). The Alcoholic Empire: Vodka and

Politics in Late Imperial Russia. New York: Oxford

University Press.

LeDonne, John. (1976). “Indirect Taxes in Catherine’s

Russia II. The Liquor Monopoly.” Jahrbücher für

Geschichte Osteuropas 24(2): 175–207.

Pechenuk, Volodimir. (1980). “Temperance and Revenue

Raising: The Goals of the Russian State Liquor Mo-

nopoly, 1894–1914.” New England Slavonic Journal

1: 35–48..

Sherwell, Arthur. (1915). The Russian Vodka Monopoly.

London:

White, Stephen. (1996). Russia Goes Dry: Alcohol, State,

and Society. New York: Cambridge University Press.

P

ATRICIA

H

ERLIHY

ALEXANDER I

(1777–1825), emperor of Russia from 1801–1825,

son of Emperor Paul I and Maria Fyodorovna,

grandson of Empress Catherine the Great.

CHILDHOOD AND EDUCATION

When Alexander was a few months old, Catherine

removed him from the care of his parents and

brought him to her court, where she closely over-

saw his education and upbringing. Together with

his brother Konstantin Pavlovich, born in 1779,

Alexander grew up amid the French cultural influ-

ences, numerous sexual intrigues, and enlightened

political ideas of Catherine’s court. Catherine placed

General Nikolai Ivanovich Saltykov in charge of

Alexander’s education when he was six years old.

Alexander’s religious education was entrusted to

Andrei Samborsky, a Russian Orthodox priest who

had lived in England, dressed like an Englishman,

and scandalized Russian conservatives with his pro-

gressive ways. The most influential of Alexander’s

tutors was Frederick Cesar LaHarpe, a prominent

Swiss of republican principles who knew nothing

of Russia. Alexander learned French, history, and

political theory from LaHarpe. Through LaHarpe

Alexander became acquainted with liberal political

ideas of republican government, reform, and en-

lightened monarchy.

In sharp contrast to the formative influences on

Alexander emanating from his grandmother’s court

were the influences of Gatchina, the court of

Alexander’s parents. Alexander and Konstantin

regularly visited their parents and eight younger

siblings at Gatchina, where militarism and Pruss-

ian influence were dominant. Clothing and hair

styles differed between the two courts, as did the

entire tone of life. While Catherine’s court was dom-

inated by endless social extravaganzas and discus-

sion of ideas, Paul’s court focused on the minutiae

of military drills and parade ground performance.

ALEXANDER I

31

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

The atmosphere of Gatchina was set by Paul’s sud-

den bursts of rage and by a coarse barracks men-

tality.

Alexander’s early life was made more compli-

cated by the fact that Catherine, the present em-

press, and Paul, the future emperor, hated each

other. Alexander was required to pass between

these two courts and laugh at the insults which

each of these powerful personages hurled at the

other, while always remaining mindful of the fact

that one presently held his fate in her hands and

the other would determine his fate in the future.

This complex situation may have contributed to

Alexander’s internal contradictions, indecisiveness,

and dissimulation as an adult.

ALEXANDER’S MARRIED LIFE

When Alexander was fifteen, Catherine arranged a

marriage for him with fourteen-year-old Princess

Louisa of Baden (the future Empress Elizabeth) who

took the name Elizabeth Alexeyevna when she con-

verted to Russian Orthodoxy prior to the marriage.

Although Alexander’s youth prevented him from

developing a passionate attachment to his wife,

they became confidants and maintained a luke-

warm relationship for the rest of their lives. Their

relationship endured Alexander’s long-term liaison

with his mistress, Maria Naryshkina, his flirtations

with a number of noblewomen throughout Europe,

and rumors of an affair between Alexander’s wife,

Elizabeth, and his close friend and advisor, Adam

Czartoryski. Czartoryski was reputed to be the fa-

ther of the daughter born in 1799 to Elizabeth.

Alexander and Elizabeth had no children who sur-

vived infancy.

THE REIGN AND DEATH OF PAUL

In November 1796, a few weeks before Alexander’s

nineteenth birthday, Empress Catherine died. There

is some evidence that Catherine intended to bypass

her son Paul and name Alexander as her heir. How-

ever, no such official proclamation was made dur-

ing Catherine’s lifetime, and Paul became the new

emperor of Russia. Paul almost immediately began

alienating the major power groups within Russia.

He alienated liberal-minded Russians by imposing

censorship and closing private printing presses. He

alienated the military by switching to Prussian-

style uniforms, bypassing respected commanders,

and issuing arbitrary commands. He alienated mer-

chants and gentry by disrupting trade with Britain

and thus hurting the Russian economy. Finally, he

alienated the nobility by arbitrarily disgracing

prominent noblemen and by ordering part of the

Russian army to march to India. Not surprisingly,

by March 1801 a plot had been hatched to remove

Paul from the throne. The chief conspirators were

Count Peter Pahlen, who was governor-general of

St. Petersburg, General Leonty Bennigsen, and Pla-

ton Zubov—Empress Catherine’s last lover—along

with his two brothers, Nicholas and Valerian.

Alexander was aware of the conspiracy but be-

lieved, or told himself that he believed, that Paul

would be forced to abdicate but would not be killed.

Paul was killed in the scuffle of the takeover. On

March 12, 1801, Alexander, accompanied by a bur-

den of remorse and guilt for patricide that accom-

panied him for the rest of his life, became Emperor

Alexander I.

REFORM ATTEMPTS

Alexander’s reign began with a burst of reforms

and the hope for a substantial overhaul of Russian

government and society. Alexander revoked the

sentences of about twelve thousand people sen-

tenced to prison or exile by Emperor Paul; he eased

restrictions on foreign travel, reopened private

printing houses, and lessened censorship. Four of

ALEXANDER I

32

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RUSSIAN HISTORY

Tsar Alexander I. © M

ICHAEL

N

ICHOLSON

/CORBIS