Elsevier Encyclopedia of Geology - vol I A-E

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

When the grand old Victorian building that had

once housed the Imperial Institute was demolished to

make way for the new buildings of Imperial College,

the Directorate of Colonial Geological Surveys

moved, in 1960, to new purpose-built laboratories

and offices in Greys Inn Road, London. By this time,

inclusion of the term ‘Colonial’ in the organizations

name was becoming politically unacceptable, and it

was changed to the Directorate of Overseas Geo-

logical Surveys. Furthermore, an increasing number

of Britain’s overseas possessions were gaining inde-

pendence and this led the British Government to set

up a committee to consider, amongst other matters,

the type of technical assistance which the United

Kingdom should be in a position to provide in the

geological and mining fields and, in this context,

the future organization, structure, and functions of

the Directorate of Overseas Geological Surveys.

An End and a Beginning

The report of the ‘Brundrett’ Committee was pre-

sented to the British Parliament in May 1964. Most

of it recommendations were accepted, including the

recommendation that ‘‘the functions of the Geological

Survey of Great Britain should be expanded to cover

overseas work in the geological and mineral (see

Mining Geology: Exploration) assessment fields’’

and that ‘‘the Overseas Geological Surveys and the

Atomic Energy Division of the Geological Survey of

Great Britain should be amalgamated within the

expanded Geological Survey of Great Britain’’.In

June 1965, the amalgamation was completed with

the establishment of the Institute of Geological Sci-

ences. Overseas Geological Surveys, an integral part

of the new organization, eventually evolved into the

Overseas Division and then International Division of

the British Geological Survey, later to be renamed the

British Geological Survey where, building on the

legacy of ‘Colonial Geological Surveys’, the work of

geological surveying and assistance has continued in

many countries of the former British Empire and

in others worldwide.

See Also

Geological Field Mapping. Geological Surveys.

Mining Geology: Exploration; Mineral Reserves.

Further Reading

Dixey F (1957) Colonial Geological Surveys 1947–56, Co-

lonial Geology and Mineral Resources Supplement

Series, Bulletin Supplement no 2, p. 129. London:

HMSO.

Dunham KC (1983) Frank Dixey 1892–1982. Bibliograph-

ical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society 159–176.

Intelligence Staff of the Mineral Resources Division, Imper-

ial Institute (1943) A Review of Geological Survey Work

in the Colonies. Bulletin of the Imperial Institute, vol.

XLI, no 4. London: HMSO.

Pallister JW (1972) British Overseas Aid in the Field of the

Earth Sciences. 24th IGC, Symposium 2.

Report of the Committee on Technical Assistance for

Overseas Geology and Mining. (1964) London: HMSO.

Walshaw RD (1994) British Government Geologists

Overseas – A Brief History. Geoscientist 2: 10–12.

COMETS

See SOLAR SYSTEM: Asteroids, Comets and Space Dust

a0005 CONSERVATION OF GEOLOGICAL SPECIMENS

L Cornish and G Comerford, The Natural History

Museum, London, UK

Copyright 2005, Natural History Museum. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

This article covers the general ethics and methodolo-

gies of conservation, which can be applied to all

geological material. It outlines best practice when

carrying out both preventive and remedial conserva-

tion. Examples are given of unstable material and

how to approach treatment. The further reading list

will allow the reader to explore specific conservation

issues.

There is no international standard for the care and

conservation of fossils. Natural history specimens in

CONSERVATION OF GEOLOGICAL SPECIMENS 373

general do not automatically fall under the protection

of the UNESCO treaty. A great deal depends on the

enabling legislation passed by individual countries.

A single collection may contain materials as diverse

as unaltered organic material, bone, shell, amber, and

a very wide range of rock, mineral, and sediment

materials. Fossils by their very nature can be preserved

in isolation or in a rock matrix, and as such the com-

positions of the specimen and the surrounding matrix

have to be considered as one unit for conservation

purposes. The term fossil has therefore been used to

encompass a range of geological material.

Preventive Conservation

Preventive conservation is an important part of pro-

longing the life of an individual specimen or collec-

tion. There are two distinct aspects to preventive

conservation: the organizational and the technical.

This article concentrates on the technical aspect,

whilst appreciating that in large organizations the

management of human resources and the physical

environment are required to produce good preventive

conservation practice. Preventive conservation is

everyone’s responsibility and not just the preserve of

an individual conservator. Preventive conservation

involves indirect action to slow deterioration and

prevent damage by creating conditions that are

optimal for the preservation of the object.

Handling

All specimens should be handled with care; even those

that appear robust can be damaged by inappropriate

handling. The basic principles of handling include:

.

cleanliness – use clean bare hands or disposable

gloves;

.

avoid unnecessary handling;

.

assess the weight and condition of the object;

.

check for any breakages, cracks, or old repairs;

.

handle specimens one at a time;

.

handle associated pieces separately;

.

support the specimen fully when picking it up;

.

use supports to carry specimens that are fragile or

cannot carry their own weight;

.

use a trolley or similar device to move objects that

are heavy;

.

do not drag or push a specimen across a surface;

and

.

provide protection against environmental changes

for specimens that are being moved to an area with

different environmental conditions.

The first step in preventive conservation is to

ensure that specimens are handled correctly. Speci-

mens should be fully supported during transportation

from the storage area to the study area. Large speci-

mens are in danger of failing in weak areas if they are

held at only one point. Before picking up a specimen,

a brief assessment should be made, noting any vulner-

able areas. Strain should not be placed on cracks or

joins, and surfaces that are flaking or friable should

be avoided. Scratching of highly polished surfaces

should be avoided. Absorption of dirt, oil, and salts

from the hands can occur if the specimen has a porous

surface (e.g. limestone). Large specimens require

thick soft padding to support them (e.g. high-density

polyethylene). Specimens that are being moved from

one set of environmental conditions to another

should be packed to ensure a slow acclimatization.

Storage

The correct storage of specimens will prevent un-

necessary damage arising through abrasion and

stacking. Ensuring that each specimen is housed

correctly and fully supported in storage will avoid

physical damage.

.

Small objects stored in drawers may be placed in

boxes or trays. These trays should be of adequate

size and lined with a supporting material.

.

Small specimens may be stored in drawers lined

with foam and placed in cut-outs.

.

Boxes or trays should be of such a size that they

tessellate within a drawer, preventing trays moving

when the drawer is opened or closed.

.

Larger specimens may require bespoke mounts to

ensure that they are fully supported.

.

Mounts should be lined with inert foam to en-

sure that there is no adverse interaction with the

specimen.

.

Very heavy specimens should be stored on

foam-lined boards that incorporate supports for

vulnerable parts.

Packaging Materials

All materials that come into direct contact with a

specimen should be inert, in that they should not

damage the specimen through abrasion or chemical

interaction. The materials used to store and display

specimens should be made from conservation-grade

substances. Foams that are used to support specimens

and absorb vibration should not be made from ma-

terials that degrade rapidly. A closed-cell inert-nitro-

gen-blown polyethylene foam that is highly chemical

resistant and stable in the presence of ultraviolet radi-

ation is a suitable foam for use in storage. This type of

foam can be purchased in varying densities, and the

density should be chosen according to the weight of

the specimen. Larger specimens should be stored on

foam-lined shelves or pallets. Other materials such as

374 CONSERVATION OF GEOLOGICAL SPECIMENS

tissue used to pack specimens for travel should be

acid free, as should the trays and boxes in which

specimens are stored within collections.

Environmental Conditions

Many rocks and minerals are environmentally sen-

sitive. Environmental factors affecting specimens

include light, heat, dust, relative humidity, and

pollutants. Some mineral specimens may change

colour owing to their sensitivity to light. Crystals

may fracture if they are exposed to heat or to cycles

of hot and cold temperatures. Dust can be potentially

damaging to specimens as it disfigures surfaces and

encourages corrosion by providing nucleation sites

for the absorption of water and other pollutants.

Where specimens have been remedially treated with

adhesives or consolidants, dust can sink into the poly-

mer surface and subsequently be very difficult to

remove. Pyrite, clay, shale, and subfossil-bone speci-

mens may split and crack if they are stored at an in-

appropriate or fluctuating relative humidity. Pollutants

can occur in materials associated with the specimen, in

other objects in the collection, and in the surrounding

air. Materials that are known to release harmful

vapours at room temperature include wood – particu-

larly oak, birch, and chipboard. These materials should

be avoided for use in storage as the vapours given off

may react with some mineral specimens. The best en-

vironment in which to store rock and mineral speci-

mens is dust free and clean, with low light and

moderate temperature and humidity levels.

Light

Light-sensitive specimens or specimens whose sensi-

tivity to light is unknown should be housed in light-

proof storage. Where specimens are to be displayed,

the effects of light should be minimized by one or

more of the following methods:

.

excluding daylight;

.

using low-ultraviolet light sources;

.

using ultraviolet filters;

.

using display methods that ensure that the speci-

mens are lit only whilst they are being viewed; and

.

rotating the specimens between display and low-

light storage.

Relative Humidity and Temperature

In purpose-built collection storage it is possible to

specify particular values of relative humidity and

temperature. A stable environment is paramount to

providing a stable collection. Heat can damage spe-

cimens through simple excess or indirectly when

it is introduced suddenly into an unheated space,

destabilizing the relative humidity. Fluctuating

relative humidity can lead to physical damage of

some specimens. Increased moisture in the air can

lead to the dissolution of specimens through the ab-

sorption of water from the environment. Conversely,

loss of water to the environment can lead to changes

in the chemical composition and properties of some

minerals. Suitable environments for mineral, rock,

and fossil collections are those with stable relative

humidity and temperature. A temperature between

15

C and 21

C, fluctuating by no more than 1

C,

and a relative humidity of 45% 5% would be

suitable for most geological collections.

Where the specimen storage environment is unsuit-

able, microclimates may be created using humidity

buffers. The buffering material, commonly a silica-

based product available from conservation suppliers,

can be purchased in bead, sheet, or cassette form. The

buffers work by absorbing and releasing moisture

from the enclosed air. Individual specimens can be

placed in a sealed polyethylene container with an

appropriate quantity of this material, and a constant

humidity will be maintained for a period. The more

often the container is opened, the more quickly the

buffer will become spent and require recharging.

Where specimens are too large to fit into polyethylene

containers, microclimates can be produced by encap-

sulating the specimen in a buffer in a moisture-barrier

film sealed with a heat sealer. These methods work

very well for individual specimens but alternatives are

required for larger collections of humidity-sensitive

material.

Environmental Monitoring

The environment of the collection or specimen re-

quires monitoring. This can be done in a number of

ways, depending on the size of the task and the funds

available. Simple humidity-indicator cards can be

placed with the specimen to give a general indication

of the amount of moisture in the atmosphere. Dial

hair hygrometers will give a more specific reading,

and recording thermohygrographs will give a weekly

or monthly trace. These methods all have their uses,

albeit limited. Electronic data loggers are more useful;

they are programmed and the data downloaded using

a computer. The data are then more easily analysed.

Radio telemetric systems and building management

systems give real-time data. This type of monitoring

allows the environment to be measured remotely

and is very useful inside microclimates such as dis-

play cases where buffering agents have been used or

in places that are remote or difficult to access

(Figure 1). Sensors are commonly used to control the

environments of buildings housing collections. In the

past, data from building management systems have

been of little value to the preventive conservator for

CONSERVATION OF GEOLOGICAL SPECIMENS 375

recording the environmental conditions. Generally,

these sensors were part of a complex control system,

and expensive specialist software was needed to view

the values. They also recorded data in formats that

were difficult to export. Recording of building man-

agement system data can now be easily configured via

an internet browser, and, importantly, the data can be

retrieved simply and analysed using standard

graphing software. High-quality building manage-

ment system sensors have now been developed that

allow simple checking and re-certification by conser-

vators using low-cost certified handheld monitors.

Collection Surveys

The collection survey is an essential component of an

environmental strategy and is used to determine the

physical state and future needs of the collection

(Figure 2). For large collections, statistical sampling

methods may be needed to reduce the time and money

spent on the survey. A formal documented inspection

or survey will highlight problems in a collection. Typ-

ically information documented would include

damage, surface pollutants, decay, environmental

sensitivity, previous conservation treatment, style of

storage, and environment. Once an overall picture of

the collection has been built, a procedure for bringing

the collection up to an acceptable standard can be

determined.

Integrated Pest Management

Insect pests can cause major problems for a natural

history collection. Although pests rarely damage geo-

logical material, the accompanying documentation

may be affected. The pesticides that were generally

used to stop pest infestations are no longer used

because of the risk they pose to health. It is advisable

to monitor collections through trapping so that po-

tential infestations can be prevented. In large organ-

izations the approach to preventing pest damage is

known as integrated pest management.

Mould

Preventing contamination by fungal spores within any

building is impossible. However, mould growth can be

prevented by ensuring that the conditions for germin-

ation do not arise in the stores or display areas. Uncon-

trolled indoor environments may experience extreme

seasonal changes, allowing humidity levels to rise to

the point where germination of spores occurs. If rela-

tive humidity is maintained at sufficiently low levels,

outbreaks will not occur. Levels of between 50% and

60% relative humidity are considered safe and will not

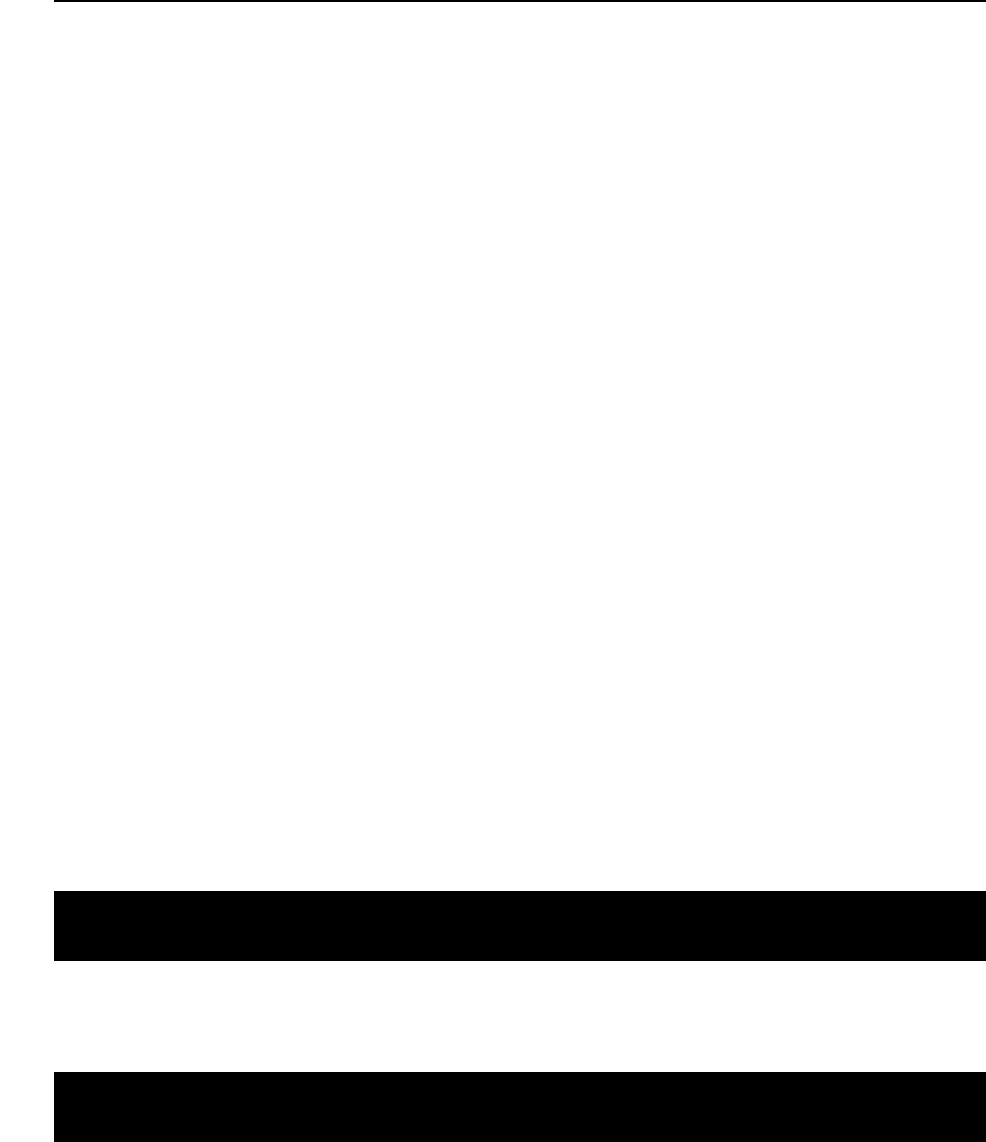

Figure 1 Moa bird on display monitored by telemetry.

Color

Image

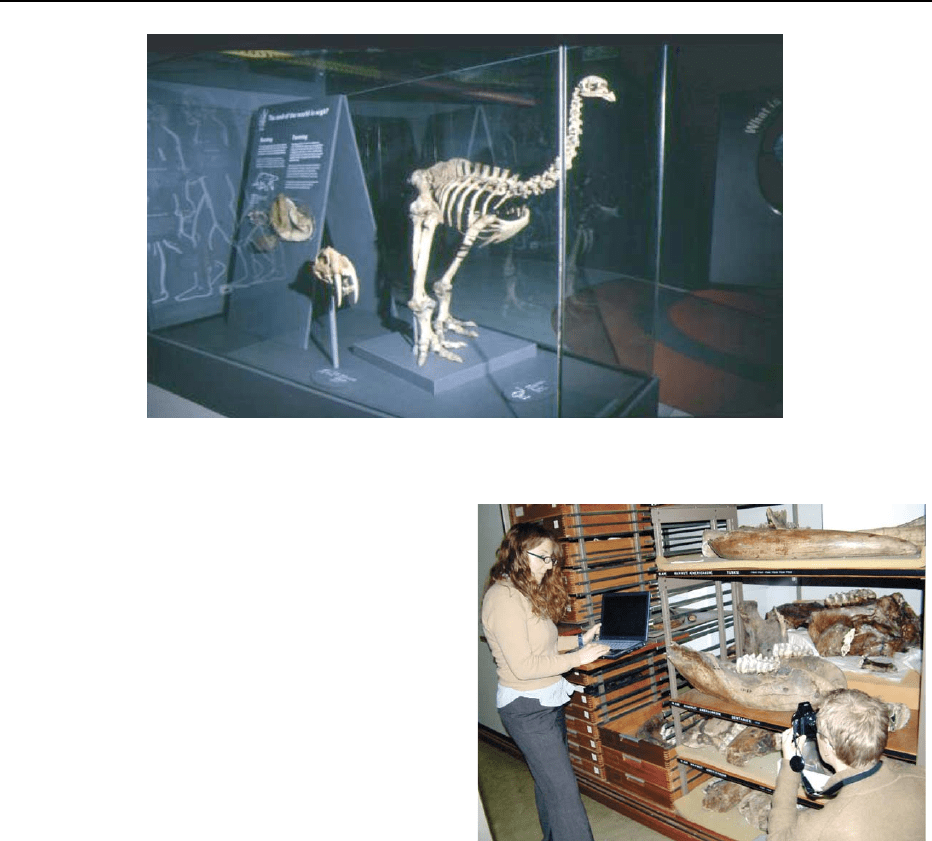

Figure 2 Survey being carried out on sub fossil bone mammal

collection.

Color

Image

376 CONSERVATION OF GEOLOGICAL SPECIMENS

allow such growth. When an infestation is encountered

the steps to take are:

.

confine it;

.

stop its growth;

.

eradicate it; and

.

prevent it from reoccurring.

Reduced Oxygen Environments

Reduced oxygen environments are cost-effective low-

impact methods of controlling the deterioration of

specimens that are sensitive to oxygen, water vapour,

or pollutants. Any rock or mineral specimen that is

sensitive to oxygen, water vapour, or pollutants (such

as rocks containing pyrite that is likely to oxidize or

has begun oxidizing) can be stored in reduced oxygen

environments to prolong their life. There are three

components to a reduced oxygen environment: an

oxygen scavenger or oxygen-purging system; an

oxygen monitor; and a barrier film. Oxygen scaven-

gers are composed of either iron filings or molecular

sieves such as zeolite or mordenite. The optimum

composition of a barrier film for this purpose is cur-

rently under research. Commercially available films

are currently composed of materials chosen to suit

either the food or the electronics industries, and,

whilst these films may be useful for preventive conser-

vation, they may not be the optimum. Barrier films are

layered polymers combined to produce a film with

good tear strength, low water migration, and low

oxygen migration. The enclosure is made by wrapping

the specimen in the barrier film and using a heat sealer

to close the film and finish the encapsulation. The

specimen should be supported in conservation grade

materials to ensure that no physical stresses are im-

posed on the specimen and no damage is created by

the abrasion of the film on its surface (Figure 3).

Remedial Conservation

Remedial conservation consists mainly of direct

action carried out on an object with the aim of

retarding further deterioration.

One of the most important and sometimes contro-

versial stages of conservation treatment is surface

cleaning. Irreversible damage can occur if inappropri-

ate treatments are used. However, the removal from

the surface of the object of contaminants or old con-

solidants that may otherwise cause harm is highly

advantageous. For example dust can contain acidic

particles that can cause surface damage. In some cases

cleaning may also clarify an object’s detail or reveal

unseen damage that can be treated subsequently.

Joins that require repair also have to be surface

cleaned to improve the final bond. There are many

types of surface-cleaning techniques available to

the conservator, and they tend to be divided into

mechanical cleaning and chemical cleaning.

Surface Cleaning: Mechanical

Abrasive Abrasive cleaning methods include all

techniques that physically abrade the fossil surface

to remove contaminants or coatings. Such techniques

involve the use of materials that impact or abrade

the surface under pressure, or abrasive tools and

equipment. The use of water in combination with

abrasive powder may also be classified as an abrasive

cleaning method. Depending on the manner in which

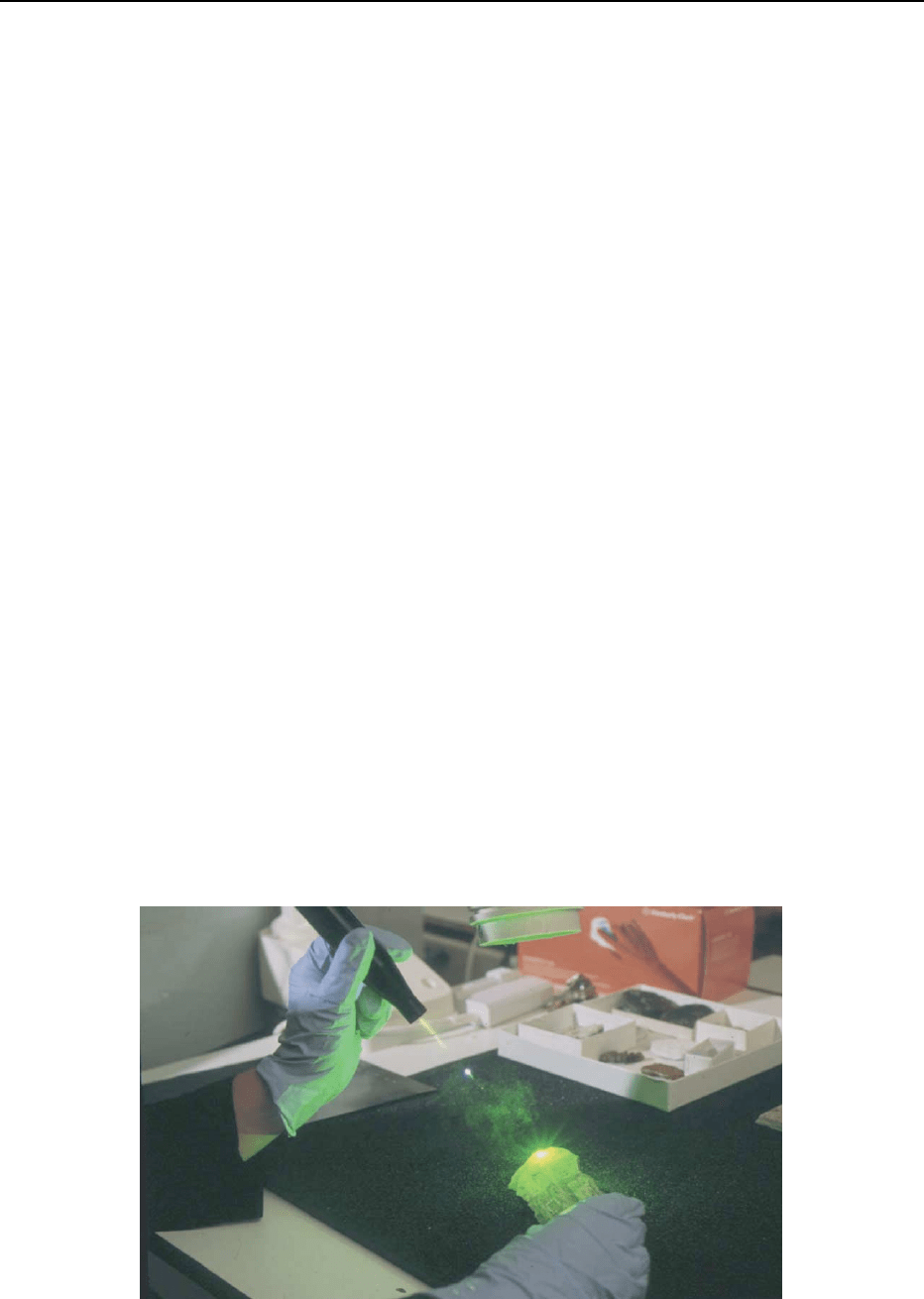

Figure 3 Pyritised ammonite encapsulated in barrier film in an oxygen free environment.

Color

Image

CONSERVATION OF GEOLOGICAL SPECIMENS 377

it is applied, water may soften the impact of the

powder, but water that is too highly pressurized can

be very abrasive.

Steam cleaning Steam, heat, and pressure provide

the means for the immediate removal of particles

from a given surface, cleaning it thoroughly. This

technique is usually carried out using of a handheld

steam pencil and is especially useful for removing old

adhesives and labels.

Ultrasonic Ultrasound is used in the cleaning of

material because of its vibration rates. Large acoustic

forces break off particles and contaminants from

surfaces. This cleaning method is generally carried

out either by immersing the specimen in a tank or

by using a handheld pen. When the latter is used, its

vibrating tip contacts the surface and fragmentation

occurs. When fossils are immersed in a tank of liquid

(usually water and detergent), sound waves from the

transducer radiate through the tank, causing alternat-

ing high and low pressures in the solution. During

the low-pressure stage, millions of microscopic

bubbles form and grow. This process is called cavita-

tion, meaning ‘formation of cavities’. During the

high-pressure stage, the bubbles collapse or im-

plode, releasing enormous amounts of energy. These

implosions work in all directions, on all surfaces.

Laser cleaning Surface cleaning by laser is a recent

innovation in the treatment of geological material

and presents several advantages when compared

with standard cleaning methods. The laser offers the

potential for selective and controlled removal of

surface contaminants with a limited risk of damaging

the underlying substrate. When the laser beam meets

a boundary between two media, e.g. dirt and the

sample surface, a proportion of the beam’s energy is

reflected, part is absorbed, and the rest is transmitted

(Figure 4). The proportion of energy absorbed is de-

termined by the wavelength of the radiation (primary

source) and the chemical structure of the material. In

order to remove dirt or another unwanted surface

coating from an object, it is important that the dirt

or coating absorbs energy much more strongly than

the underlying object at the selected laser wavelength.

If this is the case then, once the dirt layer has been

removed, further pulses from the laser are reflected

and the cleaned surface is left undamaged. The tech-

nique, therefore, is – to a certain degree – self limiting.

Cleaning efficiency can also be enhanced by brushing

a thin film of water onto the surface immediately

prior to laser irradiation. The laser also effectively

removes conducting coatings, for example gold or

palladium, from microfossils; these have previously

been almost impossible to remove.

Surface Cleaning: Chemical

Surface cleaning by using chemicals should be con-

sidered carefully so that the integrity of the object is

not compromised. A disadvantage of using chemicals is

the inability to control the chemical movement within

an object, which can lead to over cleaning and the

unwanted removal of fossil material. Usually a chem-

ical-cleaning testing regime should be carried out, com-

mencing with the least aggressive solvent. A solvent is a

liquid capable of dissolving other substances.

Care should be taken to ensure that the physical

and chemical properties of the fossil and surrounding

matrix (where present) are taken into account so that

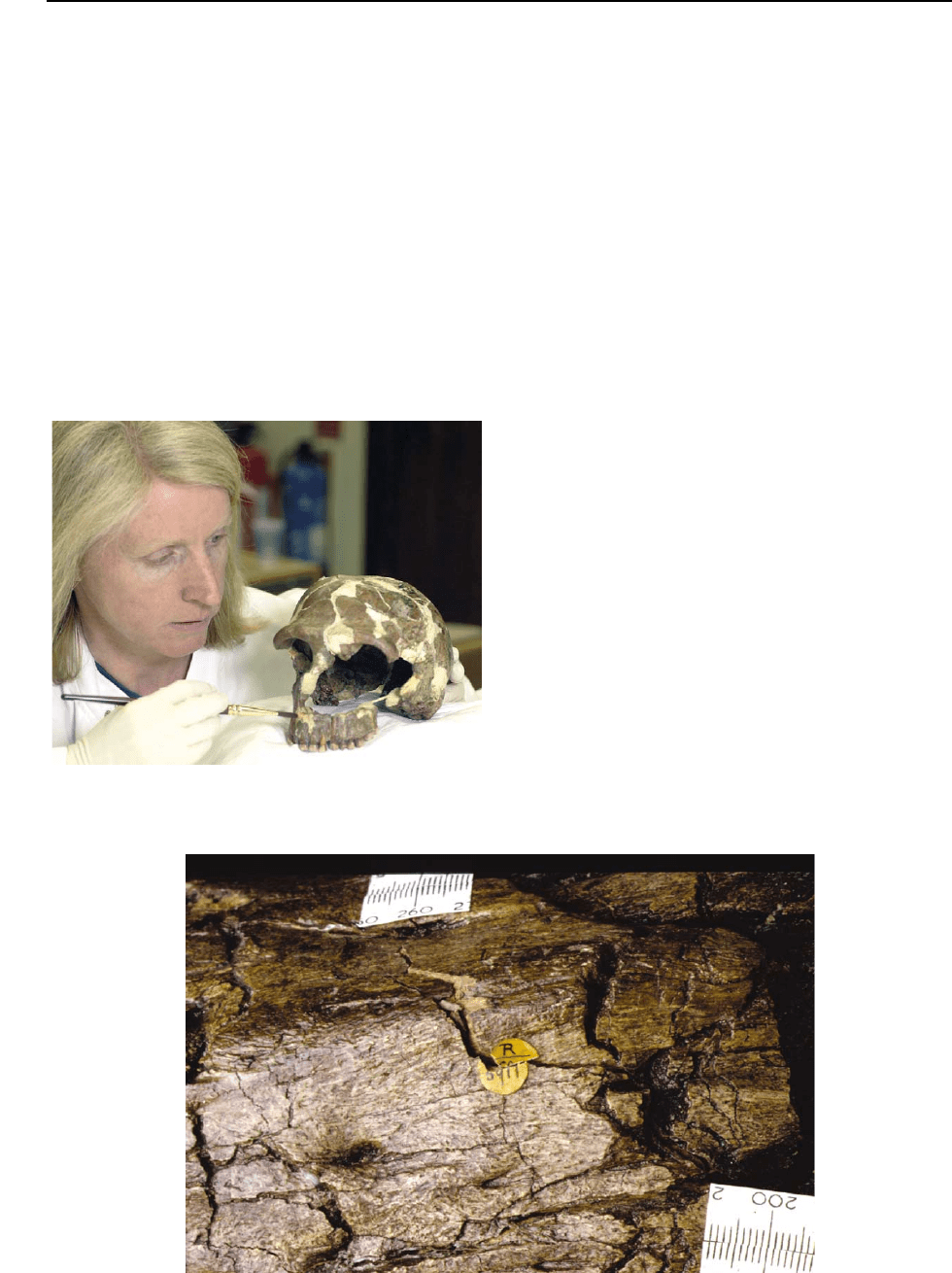

Figure 4 Laser cleaning of fossil reptile (indet) and surrounding matrix. Visible green wavelength (533 nm) being used.

Color

Image

378 CONSERVATION OF GEOLOGICAL SPECIMENS

inappropriate use is avoided. For example, water is

non-hazardous to the conservator and the strong po-

larity of its molecules means that it is effective in

removing a wide range of pollutants. However, this

apparently harmless material would have severe

detrimental effects on humidity-sensitive pyritized

fossils, causing them to deteriorate.

Poulticing is used to avoid deep penetration and

to limit the action of chemicals on the object. Chem-

icals are mixed with absorbent powders to form a

paste or poultice, which is applied to the surface.

As the poultice dries, dirt is drawn out and has to

be physically removed. A development of this tech-

nique is the use of solvent gels. These cleaning systems

have an aqueous gel base composed of a polymer

resin that thickens on the addition of water, and a

surfactant – also a thickening agent – which improves

the gel’s contact with the surface to be cleaned. Any

number of cleaning agents can be added to this gel

base. Of particular concern to the conservator are the

possible long-term effects on surfaces. The most

pressing concern has been whether any residue of

the gels is left on the treated surface that may cause

future damage.

Consolidants, Adhesives, and Gap Fillers

The consolidants, adhesives, and gap fillers used

at any given time reflect the existing knowledge

of chemistry and technology; so, naturally, their di-

versity and quality change over time. From the view-

point of the conservator, all should be reversible.

Geological material, whether it is in scientific collec-

tions or in a private collection, must be considered

valuable and irreplaceable. As such, conservationally

sound and approved materials should be used

wherever possible.

Consolidants When considering whether to use a

consolidant on a specimen, it is important to remem-

ber that not all specimens require consolidation. The

most important axiom of conservation is: minimal

intervention is best.

A consolidant is a liquid solution of a resin (nor-

mally a synthetic polymer) that is used to impregnate

a fragile object in order to strengthen its structure.

Common solvents for the resins are water, acetone,

alcohol, and toluene. Consolidants are generally

available in two forms: pure resins and emulsions.

Pure resins are mixed with their solvents to form a

very thin watery solution, which is then applied to

the specimen (or the specimen is immersed in the

solution). The aim is to get the solution to pene-

trate the specimen’s surface and carry resin down

into the interior of the fossil bone: the consolidant

must be thin otherwise it will be deposited on the

surface of the bone only, like the shellac or varnish

used in the past. Those treatments may have pro-

tected the surface, but did little to strengthen the

whole bone.

The second class of consolidants, the emulsions,

are mainly used to treat wet or moist specimens.

Emulsions are suspensions, in water, of a resin and

solvent solution, popularly polyvinyl acetate emul-

sion, and are generally white milky mixtures. Emul-

sions are not as desirable as pure resins. It is hard to

reverse emulsions once they have dried and virtually

impossible once they have crosslinked on exposure to

ultraviolet light from the sun or from fluorescent

bulbs. Emulsions also tend to turn yellow with age

and increasing crosslinking.

Adhesives and gap fillers Historically, the most

common adhesives have been animal glues made

from bones, fishes, and hides, and these were used

extensively for fossil repair and can still be purchased

today. Owing to their inherent problems, such as

yellowing, brittleness, and instability, they are no

longer used on fossils. Consisting mainly of colla-

gen–protein slurries, animal glues are also quite at-

tractive to a variety of pests. This class of adhesives is

mentioned here because of its long period of use. In

museums and at fossil auctions, it is not uncommon

to find specimens that have been repaired with these

glues.

The twentieth century has given us many new

classes of adhesives, all of which are organic polymers

– large complex molecules formed from chains of

simpler molecules called monomers. Manufacturers

may extol the virtues of the newest adhesive from

their laboratories, but only time can judge the effect-

iveness and longevity of an adhesive. Many turn

yellow with age or are prone to brittle breakage,

where even a slight jar or shock will cause the glued

joint to break. Other polymers may crosslink with

time or upon prolonged exposure to ultraviolet light,

causing shrinkage that can seriously damage a fossil

that has been repaired with them. Most of these poly-

mers have unique properties and characteristics,

which make some better for certain uses than others.

Another class of recently developed adhesives used to

repair fossils are the ‘superglues’ or cyanoacrylates.

Their characteristics, which include rapid setting and

strength, have made these adhesives increasingly

popular for fossil repair; however, since they are so

new (dating only from the 1980s), our knowledge

of their long-term efficacy is limited. A major draw-

back is the difficulty of reversing bonds made with

cyanoacrylates.

Adhesives are sometimes mixed with materials, e.g.

glass micro balloons, to form a gap filler. Gap filling is

CONSERVATION OF GEOLOGICAL SPECIMENS 379

a process whereby a sympathetic replacement mater-

ial is used to fill or bridge small or large gaps. The gap

filler should not conceal original material and should

be easy to remove (Figure 5).

Conservation of Sensitive Geological

Material

Subfossil Bone

Subfossilized bone retains a fair amount of organic

material (collagen) and original mineralized bone

(hydroxyapatite). To maintain its integrity, subfossil

bone needs to be kept in a stable environment. Once it

is removed from the matrix in which it is found, it

is likely to deteriorate rapidly, especially if it is wet

and the bone is subjected to extreme fluctuations of

temperature and humidity.

Recently excavated material that may still be wet

can be treated in two ways. The first method is the use

of water-based consolidants, which can be applied by

brushing, immersing, spraying, or vacuum impregna-

tion. The second method is slow controlled drying to

prevent cracking and delamination. The aim of con-

trolling the drying procedure is to reduce the high

relative humidity of the wet specimen slowly until it

matches that of the storage area. Even if a water-based

consolidant is used, it is advisable to apply controlled

drying procedures until the specimen is stabilized.

Smaller specimens can be placed in plastic contain-

ers, and for larger specimens a chamber or tent can be

constructed, for example by placing a piece of clear

plastic sheeting over laboratory scaffolding. Barrier

films can also be used to control drying stages. There

needs to be a controlled exchange of the moist air

inside with the lower-relative-humidity ambient air

outside the box. To monitor changes in relative hu-

midity, a humidity gauge can be placed in the contain-

ment area along with the specimen. Potential mould

growth needs to be monitored, and placing a fungi-

cide inside the containment area should control the

problem. The optimum storage environment for sub-

fossil bone has a relative humidity of 45–55% and a

temperature between 15

C and 21

C. Low relative

humidity can lead to cracking and shrinking as the

specimen dries out, and high relative humidity (above

70%) encourages damaging mould and fungal growth.

Once the specimen has been dried and stabilized,

an organic-solvent-based consolidant can be applied.

f9000 Figure 5 Neanderthal skull (Tabun) showing gap filler which

aids in its reconstruction.

Color

Image

Figure 6 Dacosuarus maximums showing severe cracking in response to fluctuating humidity conditions.

Color

Image

380 CONSERVATION OF GEOLOGICAL SPECIMENS

It is not advisable to apply water-based consolidants

to specimens that have thoroughly dried because the

high water content of the consolidant will cause the

dry specimen to swell and crack multidimensionally.

If gap fillers are to be applied to repair the bone,

particular attention should be given to the choice of

filler. Materials that shrink or expand upon curing

should be avoided as either action can damage the

specimen.

Shale and Other Fine-Grained Sediments

Deterioration in the form of delamination, cracking,

and shrinkage is common for shale and other

fine-grained sediments, especially if they are stored

in the wrong environment. The best approach

is therefore to ensure that storage conditions are

optimum, with a temperature of below 20

C and

humidity level of around 50%.

Pyrite

The deterioration and even complete decomposition

of pyritized fossils through oxidation is a common

problem (Figure 6). Deterioration is best prevented by

storing at less than 45% relative humidity. Once de-

terioration has occurred various conservation treat-

ments are available, which have varying levels of

success. For example, ethanolamine thioglycollate or

ammonia gas treatment may be used. The latter is

considered more conservationally sound.

Documentation

Existing documentation associated with individual

geological specimens should be preserved as a matter

of priority; without it the material is scientifically

useless. Any treatments should be recorded accurately

(with an image if possible) so that a history of treat-

ment can be built up over time. This information will

influence future conservation considerations.

See Also

Fake Fossils. Minerals: Definition and Classification;

Sulphides; Zeolites. Palaeontology. Rocks and Their

Classification.

Further Reading

Casaar M (1999) Environmental Management Guidelines

for Museums and Galleries. London and New York:

Routledge.

Cornish L and Doyle AM (1984) Use of ethanolamine

thioglycollate in the conservation of pyritized fossils.

Palaeontology 27: 421–424.

Cornish L and Jones CG (2003) Laser cleaning natural his-

tory specimens and subsequent SEM examination. Chapter

16 In: Townsend J, Eremin K, and Adriaens A (eds.) Con-

servation Science 2002, pp. 101–106. London: Archetype.

Cornish L, Doyle AM, and Swannell J (1995) The Gallery

30 Project: conservation of a collection of fossil marine

reptiles. The Conservator 19: 20–28.

Croucher R and Woolley AR (1982) Fossils, Minerals

and Rocks – Collection and Preservation. London:

Cambridge University Press.

Gilroy D and Godfrey I (1998) A Practical Guide to

the Conservation and Care of Collections. Perth: Western

Australian Museum.

Howie FM (ed.) (1992) The Care and Conservation of

Geological Material: Minerals, Rock, Meteorite and

Lunar Finds. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Institute of Paper Conservation. www.ipc.org.uk.

Larkin NR, Makridou E, and Comerford GM (1998) Plas-

tic storage containers: a comparison. The Conservator

22: 81–87.

Museums, libraries and archives council. http://www.mla.

gov.uk/index.asp.

Resource UK Council for Museums, Archives,Libraries

(1993) Standards in the Museum Care of Geological

Collections. London: Resource UK Council for

Museums, Archives and Libraries.

Waller R (1987) An Experimental Ammonia Gas Treat-

ment Method for Oxidised Pyritic Mineral Specimens,

pp. 625–630. Triennial Report. Rome: ICOM Committee

for Conservation.

CREATIONISM

E Scott, National Center for Science Education,

Berkeley, CA, USA

ß 2005, Elsevier Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Definitions

Although evolution is a component of many scientific

fields, it generally has the same meaning across

disciplines: cumulative change through time. The

topic of this article, ‘creationism’, is a term with

many definitions. In theology, creationism is the

doctrine that God creates new souls for each person.

In anthropology, creationism is the well-confirmed

thesis that almost all human societies have origin stor-

ies about the acts of gods, or a God, or powerful spirits

of some kind.

CREATIONISM 381

Viewed socially and politically, creationism refers

to a number of twentieth-century religiously-based

anti-evolution movements originating in the USA,

but now spreading to many countries. The most

familiar of these (and the movement to which the

term is most frequently applied) is ‘creation science’,

an attempt to demonstrate with scientific data and

theory the theological view known as special cre-

ationism. According to special creationism, God

created the universe – stars, galaxies, Earth, and

living things – in essentially their present forms.

Living things were created as ‘kinds’ that do not

have a genealogical (evolutionary) relationship to

one another. This biblical literalist theology views

Genesis narratives, such as the creation of Adam

and Eve, their sin and expulsion from Eden, and the

Flood of Noah, as historical events. In creation sci-

ence and its ancestor, ‘Flood Geology’, the Flood of

Noah has shaped most of the Earth’s geology. A recent

creationist movement, Intelligent Design Theory,

pays little attention to the Flood of Noah or to

geology, or to fact claims of any sort, contenting

itself with proclaiming God’s intermittent creation

of supposedly ‘irreducibly complex’ biochemical

structures, such as the bacterial flagellum or the

blood clotting cascade, rather than presenting

a scientific alternative to evolution. A non-Christian

creationism is promoted by the Krishna Conscious-

ness movement, whose members agree with geolo-

gists about the age of the geological column and

how it was shaped, but who argue that human arte-

facts are found from the Precambrian on, thus sup-

porting a literal interpretation of the Vedas that

humans have existed for billions of years.

Christians who opposed evolution during Darwin’s

time rarely referred to themselves as ‘creationists’;

they used the term ‘creationism’ generically to refer

to the idea that God purposefully creates living

things, in contrast with Darwin’s naturalistic explan-

ation for the appearance of humans and other crea-

tures (see Famous Geologists: Darwin). Nineteenth-

century clergy and scientists could choose from

many models of creation beyond the Biblical literalist

six 24-h days. Charles Lyell (see Famous Geologists:

Lyell) proposed that God had created animals

adapted to ‘centres of creation’ around the world;

Cuvier (see Famous Geologists: Cuvier) proposed a

series of geological catastrophes followed by a series

of creations. Theologically, the 6 days of Genesis

Creation could be interpreted as very long periods

of time (the ‘day-age’ theory), or Genesis could be

read as permitting a long period of time between

the first and second verses (the ‘gap theory’). Some

doubtless clung to a literal Genesis of six 24-h days

and a historical, universal Flood, but this view was

not common amongst university-educated scientists

or clergy.

The evolution of creationism and its relationship to

geology are the subjects of this article, and thus,

befitting an evolutionary approach, we begin with a

historical perspective.

Static versus Dynamic Views

of the Earth

Throughout much of the early European scientific

period (1600–1700), two perspectives of the world

competed: either it had remained unchanged since

the special Creation described in Genesis, or it was

changing now and had changed in the past. The shift

from a static to a dynamic view of nature was stimu-

lated by European exploration during the 1500–1700s.

During these expeditions, vast amounts of natural his-

tory, including geology, were learned by travellers and

settlers, and the new information proved to be difficult

to fit into a biblical literalist framework.

The remains of molluscs and other sea creatures on

mountaintops, found in the same groupings as living

shellfish, encouraged da Vinci to question a literal

Flood; he argued that the Flood would have mixed

up the shells, not deposited them in life-like settings.

Biological data also did not fit into the view of a static

world: new species were discovered in the new lands

that were not mentioned in the Bible, and geolo-

gists found remains of extinct species, troubling for

a theology assuming a perfect Creation. Biogeog-

raphy also made a literal Flood story problematic:

how did marsupials in Australia and South America

get there after the Ark landed on Ararat? Old views of

a static Creation, unchanged since God rested on the

seventh day, gradually gave way to an appreciation of

an evolving world and, eventually, of the evolution

of living things.

Geology is an evolutionary science, dealing as

it does with cumulative change in the history of the

planet. Geology came into its own as a scientific dis-

cipline during the 1700s, as more was learned about

the geological characteristics of the planet, prompting

speculations about the processes and mechanisms that

produced them. The fruits of fieldwork and careful

mapping illuminated such processes as sedimentation,

erosion, volcanoes and earthquakes, mountain build-

ing, and the like, and it made sense that these pro-

cesses had also operated in the past, changing the

contours of the planet. The increased understanding

of the Earth and the forces that produced its land-

forms led to the inevitable conclusion that the Earth

was ancient.

An ancient Earth, however, conflicted with trad-

itional scriptural interpretation that the Earth was

382 CREATIONISM