Elsevier Encyclopedia of Geology - vol I A-E

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

In western China, the main Muztagh-Maqen con-

vergent zone (MMCZ) in the central orogenic belt

closed in Late Hercynian to Indosinian times. The

Indosinian Jinshajiang accretion zone, extending

from West Kunlun southward to the Changning-

Menglian zone (CMAZ) in western Yunnan, marks

the boundary between the Yangtze-affiliated massifs

in the east and the Gondwana-affiliated massifs in

the west. In northern Tibet, an Indosinian suture is

suspected to exist between the North and South

Qiangtang massifs, mainly based on the occurrence

of the Late Triassic Qiangtang ophiolite complex,

which marks the southern margin of the Late Triassic

flysch complex underthrust beneath South Qiang-

tang, and on the boundary between the Cathaysian

and the Gondwanan floras (Figure 3). The wide Indo-

sinides and their southern marginal massifs, North

Qiangtang and Qamdo, may therefore represent

the southern boundary of the newly amalgamated

Laurasia Supercontinent which formed the northern

half of Pangaea (Figure 4). The boundaries of the floral

provinces are arbitrary, since mixed flora of different

provinces are known; for example, the mixed Cathay-

sian and Angaran flora in northern Tarim. The most

important world mass extinction at the end of the

Permian (ca. 250 Ma), especially that of the marine

organisms, is well represented and studied in China.

China in Post-Indosinian Times

The Indosinian Orogeny had caused a radical change

of tectonic pattern of China from a north–south to an

east–west demarcation, and the post-Indosinian

marks a megastage of mainly intracontinental devel-

opment. Jurassic and later seas retreated from China

except in the Qinghai-Tibet region, and only sporadic

marine ingressions occurred in eastern Heilongjiang,

and in the border parts of TAP and CTA. The new

tectonic framework and dynamics of China were chie-

fly controlled by interactions between the Siberia Plate

in the north, the Pacific Plate in the east, and the

India Plate in the south-west. The Indosinian Orogeny

brought about the closure of the Late Palaeozoic

Palaeotethys and the formation of the extensive Indo-

sinides, including Kunlun-Qinling, Garze-Hon Xil,

and down to Indochina and Malaysia, which formed

the southern margin of the Eurasian palaeoconti-

nent. Thus, an extensional system prevailed in

East China and a successive northward accretion of

the Gondwana-affiliated massifs onto Eurasia in the

Tethys domain has dominated West China since the

Late Mesozoic.

Post-Indosinian tectono-magmatism and basin

development in eastern China In eastern China, the

Indosinian Orogeny was followed by intracontinental

collision and further welding of platforms and

massifs, as is shown by the widespread Jurassic

A-type granites and by the southerly-imbricated

thrust zones in the Yanshan region and the westerly

thrust zones in north-eastern Anhui and western

Hunan. The large Tanlu fault, with a lateral shift of

hundreds of kilometres in length, was probably

mainly formed in the pre-Cretaceous. The newly-

formed Circum-Pacific domain comprised a western

belt of continental and maritime East China and an

eastern belt of island arc-basin systems in the inner

western Pacific. The Yanshanian Orogeny in eastern

China is characterized by inner continent marginal

type magmatism in the coastal belt (Figure 3), which

originated by subduction of the Izanaqi Plate under

East Asia. Consequently, inland eastern China was

characterized by a combination of subduction and

intra-continental collision types of magmatism, mani-

fested by muscovite/two mica granites and high potas-

sium calc-alkalic and shonshonitic volcanism. From a

comparisonbetween the crustand lithosphere thickness

data of pre-Jurassic and Jurassic-Cretaceous in North

China, based on petrogenic studies, it is found that a

crustal thickening of ca. 15 km (40 against 50–60 km)

and a lithospheric thinning of ca. 120 km (200–250

against 50–60 km) occurred in the Late Mesozoic.

This proves that eastern China changed from a com-

pressional to a tensional regime.

Mesozoic and Cenozoic basins in eastern China are

distributed in three belts. The Ordos Basin and the

Sichuan Basin in the western belt became terrestrial

inland basins in the Late Permian and Late Triassic,

respectively. Both were influenced by the Indosinian

Orogeny that formed Late Triassic foreland basin

deposits, in the southern border of Ordos north of

the Qinling Orogen, and in the Longmenshan thrust

belt of Sichuan Basin, respectively. The central belt

comprises the Cretaceous rift basins, including the

Songliao and the Liaoxi basins (bearing the Lower-

Cretaceous Jehol biota (130–120 Ma), with the well

preserved feathered dinosaur Sinosauropterix and the

earliest flowering plant, Sinocarpus), the Cenozoic

rift basins in SKP and Inner Mongolia, and the KE

rifted and volcanic basins in southern China. The east-

ern belt consists of the offshore Cenozoic rift basins

developed on the submerged palaeocontinents, which

were mainly terrestrial in the Palaeogene and marine

in the Neogene. Rifting and opening of the South

China Sea occurred in the Oligocene and Miocene,

when the SCS Massif was split into two fragments

(Figure 3, inset map).

The northward accretion of the Gondwana-affiliated

massifs to Eurasia and the formation of Qinghai-Tibet

Plateau The Gondwana-affiliated massifs with

CHINA AND MONGOLIA 353

Precambrian basement include the Himalaya, the

Gangise, the South Qiangtang, and the North Qiang-

tang. The Tianshuihai area of Karakorum, stable in

the Lower Palaeozoic, may be a part of the North

Qiangtang Massif. The Cathaysian Gigantopteris-

flora found in the Shuanghu area of North Qiang-

tang, in contrast to the Gondwanan flora found in

northern Gangdise, has led to a suspected biogeo-

graphic boundary between the North and South

Qiangtang massifs (Figure 3).

The main Tethys oceanic basin to the north of the

North Himalaya is represented by the main suture

YZCZ. The recent discovery of Cambrian to Ordovi-

cian metamorphics in the Lhagoi Kangri zone may

indicate the splitting of Gangdise from Himalaya-

India in the Caledonian Stage. Continental marginal

thick deposits appeared in the Permian to Late Trias-

sic, and the marine basin may have been at its widest

in the Jurassic. The northward subduction of the

Himalaya oceanic plate beneath Gangdise probably

began in the Late Cretaceous (ca. 70 Ma), and the

collision of the two shown occurred in the mid-

Eocene (ca. 45 Ma), as shown by the lower part of

Linzizong volcanics in Gangdise, and the final disap-

pearance of the residual seas. On the north side of

Gangdise, a southerly subducted island-arc system of

short-duration (Early Jurassic to Late Cretaceous)

formed the Bangong-Nujiang suture (BNAZ). In the

Cenozoic, intracontinental collisions resulting in ver-

tical crustal thickening and shortening were prevalent

in northern Tibet. Crustal thickening by subduction

of the Himalaya beneath the Gangdise and subse-

quent collision produced muscovite/two mica granite

of Early Miocene (ca.20–17 Ma) age in the North

Himalaya. In contrast, collision between adjacent

massifs without subduction were more frequent and

formed shonshonitic volcanism, as in the northern

volcanic belt of North Qiangtang in the Oligocene.

The Himalayan Orogeny and uplift of the Plateau

occurred in two stages; Oligocene and Pliocene to

Pleistocene (Figure 2).

It has been estimated that no less than 1000 km of

north-south crustal shortening has occurred since the

Early Palaeogene collision between Himalaya-India

and the northern massifs, which has led to the even-

tual uplift of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Except for

the northward subduction of the Himalaya beneath

Gangdise, the shortening was mostly accommodated

by distributed vertical thickening of the crust, and

the main strike-slip faults and thrust belts. The east-

ward extrusion of the Plateau in the Sanjiang belt of

eastern Tibet is significant, but may not be vital in the

Plateau construction. The northward indentation

from Himalaya-India has been prevalent, but the

southward indentation from the rigid Tarim craton

and the Beishan massif is equally important in the

overall dynamics of western China.

Geology of Mongolia

Tectonic Units and Tectonic Stages of Mongolia

Mongolia is situated in the central part of the wide

and complicated orogenic belts between the Siberian

Platform in the north and the North Chinese plat-

forms SKP and TAP in the south. Mongolia is subdiv-

ided into a northern domain and a southern domain,

the boundary between which runs roughly along the

southern margin of the Gobi-Altai-Mandaloovo

(GAB) Belt of Caledonian age (Figure 5).

Three megastages may be recognised in the crustal

evolution of Mongolia, approximately correspond-

ing to the megastages of China. They are: (i) Neoarch-

aean (An) to Early Neoproterozoic (ca. 850 Ma);

(ii) Late Neoproterozoic to Triassic, including the

Salairian, Caledonian and Hercynian Orogenies; and

(iii) Indosinian stages, the Mesozoic to Cenozoic, char-

acterized by intracontinental development (Figure 2).

Mongolia in the Neoarchaean to the

Early Neoproterozoic

The oldest rocks of Mongolia are found in the

Neoarchaen Baidrag Complex in the southern part

of the Tuva-Mongolia Massif (TMM), where a tona-

lite-gneiss has yielded a U-Pb zircon isotopic age of

2 646 45 Ma. In the same region, the Bumbuger

Complex of granulite facies has a metamorphic zircon

age of 1839.8 0.6 Ma, which is coeval with the Lu-

liangian Orogeny of China. Palaeoproterozoic massifs

with reliable isotopic age dating are distributed in

the TMM (Figure 5). A metamorphic age of

ca. 500 Ma was obtained from the northern part

of TMM (Songelin block), which may be attributed

to the influence of the Salairian Orogeny in the region.

In southern Mongolia, Palaeoproterozoic rocks may

exist in the east-west trending Hutag Uul Massif

(HUM) and Tzagan Uul Massif (TUM) near the

southern border part of Mongolia.

Mesoproterozoic to Early Neoproterozoic rocks

are widespread and form the main Precambrian base-

ment in Mongolia. In northern TMM, the Hugiyngol

Group, composed of metabasalts and metasedi-

ments including blue schists, have a metamorphic age

of 829 23 Ma. In the Mongol Altai Massif (ATM)

and adjacent part of China, the thick Mongol-Altai

Group, composed of highly mature terrigenous de-

posits, is unconformably overlain by fossil-bearing

Ordovician beds. Sm-Nd model ages of ca.1400–

1000 Ma, obtained in westernmost Mongolia and

adjacent parts of China, indicate the Precambrian age

354 CHINA AND MONGOLIA

of the Mongol-Altai Group Meso- and Neoprotero-

zoic sequences, including stromatolitic carbonates that

occur in the southern belts of TMM and in AMM

(Figure 5) in north-eastern Mongolia, which may be

partly regarded as paracover strata on the ancient

basement, as is the case in TAP and SKP of China.

Mongolia in the Late Neoproterozoic to

the Triassic

The Salairian Stage (Late Neoproterozoic to Early

Cambrian) The Salairian Stage, ranging from Late

Neoproterozoic to Early Cambrian in age, is import-

ant in Mongolia. Well-developed Salairian orogenic

belts are distributed in western Mongolia and are

composed of Vendian to Cambrian siliciclastics, car-

bonates, and volcanics that were probably partly

formed in an archipelagic ocean basin with island

arcs and sea-mounts. Recent studies of the accom-

panying ophiolites have yielded U-Pb zircon ages of

568–573 Ma and Sm-Nd ages of ca. 520 Ma in many

places, which are in conformity with the ages formerly

determined by fossils. Synorogenic granites in

the Lake area bear isotopic ages of Middle to Upper

Cambrian. In northern Mongolia, there are two

northeast-trending Salairian orogenic belts (DB

and BB) extending eastwards into Russia, in which

post-orogenic granites of Ordovician age are found.

Research on the well-known Bayanhongor ophio-

lite zone, which is situated in a Caledonian Belt, has

revealed that the ophiolites was emplaced by obduc-

tion in the time interval 540–450 Ma of Salairian age.

A discontinuous belt, indicating the Salairian Or-

ogeny, is known near Choibalsan in north-eastern

Mongolia, which may have some connection with

the Salairian Belt in the Okhotsk region (Figure 1).

In view of the discovery of granites of Salairian age

on the western border of the Jamus-Xingkai Massif

of China (Figure 3), it seems that the Salairian Or-

ogeny was active in both eastern Mongolia and

north-eastern China.

The Caledonian stage (Middle Cambrian to Silurian)

In the Hovd Caledonides of western Mongolia, the

Lower Palaeozoic sequence, consisting of thick flysch

of Tremadocian and older ages, and unconformably

overlying Ordovician and Silurian carbonates and

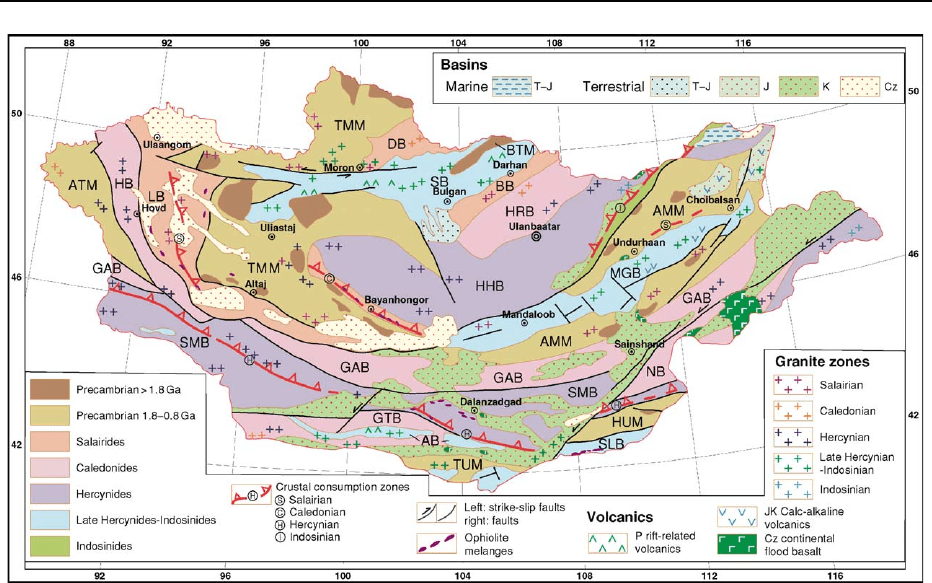

Figure 5 Outline tectonic map of Mongolia. Compiled and integrated from the Geological Map of Mongolia, 1:5 000 000, published by

Institute of Geology and Mineral Resources, 1998, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

Tectonic units. Northern Mongolia: TMM Tuva-Mongolia Massif, AMM Arguna-Mongolia Massif, ATM Altai-Mongolia Massif, BTM

Buteel Massif, LB Lake Salairian Belt, BB Bayangol Salairian Belt DB Dzhida Salairian Belt, HB Hovd Caledonian Belt, HRB Haraa

Caledonian Belt, GAB Gobi Altai-Mandalovoo Caledonian Belt. HHB Hangay-Hentey Hercynian Belt, SB Selenge Late Hercynian-

Indosinian Belt, MGB Middle Gobi Late Hercynian-Indosinian Belt. Southern Mongolia: TUM Tsagan Uul Massif, HUM Hutag Uul

Massif, NB Nuketdavaa Caledonian Belt, GTB Gobi Tienshan Caledonian Belt, SMB South Mongolian Hercynian Belt. AB Atasbogd

Late Hercynian-Indosinian Belt, SLB Sulinheer Late Hercynian-Indosinian Belt.

Color

Image

CHINA AND MONGOLIA 355

clastics, with mafic and intermediate volcanics, are

well developed. In central and eastern Mongolia, the

Ordovician–Silurian sequence in the Gobi-Altai-

Mandalovoo (GAB) Caledonian Belt includes a

lower and an upper part separated by an unconform-

ity, and both parts were much reworked in the

Hercynian Orogeny. This extensive east-west trending

belt (GAB) may mark the southern margin of the Early

Palaeozoic northern Mongolian palaeocontinent. In

southern Mongolia, in the Caledonian Gobi-Tianshan

Belt (GTB), Ordovician to Silurian metasediments,

with intercalated metavolcanics, are unconformably

overlain by Devonian clastic desosits. Similar se-

quences are observed in the adjacent Junggar region

of China. Thus the Caledonian Orogeny played an

important role both in southern Mongolia and

north-western China.

The Hercynian and Indosinian stage (Devonian to

Triassic) The Early Hercynides of mainly Devonian

to Early Carboniferous age are predominant in

southern Mongolia. The South Mongolian Hercynian

Belt (SMB) represents the main belt of Late Palaeozoic

crustal increase in southern Mongolia and extends on

both ends into China. To the west, it is continuous

with the Ertix-Almantai zone in China and further

to the west with the Zaysan fold zone in Russia

(Figures 1 and 3). The Upper Palaeozoic in the central

part of SMB is composed mainly of Devonian and

Lower Carboniferous arc-related volcanics and clas-

tics, including some Upper Silurian beds in the basal

part. The ophiolite me

´

lange zones within SMB are not

continuous, and were evidently later dismembered.

The lower part of the sequence includes the Berch

Uul Formation consisting of a thick sequence of

uppermost Silurian to Devonian tholeiitic pillow

lavas, andesites, and tuffs, and Upper Devonian inter-

mediate to felsic volcanics and olistostromes with coral

limestone clastics. Frasnian conodonts and intrusive

rocks dated at ca. 370 Ma are found in the arc-related

volcanics. The upper part of the sequence comprises

Lower Carboniferous fine-grained sandstones and

mudstones with rich shallow marine fossils, which

may have been formed after collision, although pyro-

clastic beds denoting volcanic activities are known to

occur. In the Precambrian ATM, the Caledonian Hovd

Belt (HB) and other parts of northern Mongolia, Dev-

onian carbonates and clastics with felsic to intermedi-

ate volcanic beds are widespread as cover strata on the

basement.

Thick Devonian flysch-like deposits are also de-

veloped in the broad central Mongolian Hangay-

Hentey (HHB) Belt. The main part of HHB were

folded after the Early Carboniferous, but a residual

sea trough seems to have lingered on the eastern side

of its north-eastern segment, which was essentially

closed in Indosinian time. The resultant narrow Indo-

sinide (Figure 5) sea extended to Russia and was

probably continuous with the Mongol-Okhotsk

seaway that finally closed in the Jurassic.

The Late Hercynian and Indosinian are usually in-

separable in Mongolia. They are the Selenge Belt (SB)

in northern Mongolia, the Middle Gobi Belt (MGB)

in eastern Mongolia, the Sulinheer Belt (SLB), and the

Atasbogd Belt (AB) in southern Mongolia. The latter

belt extends both eastwards and westwards into

China. All the belts are characterized by thick se-

quences of bimodal aulacogen volcanics, volcaniclas-

tics, and pyroclastics of Late Carboniferous to Early

Permian age dated by plant remains. To a certain

extent, they are comparable with the sequence in the

Bogda Mountains, which is a Carboniferous aulaco-

gen that separated the Junggar and Tuha massifs in

northern Xinjiang, China. There is, however, an alter-

native suggestion that a Carboniferous to Permian

arc-basin system may have developed in the SLB on

the southern border of Mongolia, which is continuous

with the Late Hercynides–Early Indosinides belt in

Inner Mongolia (Figure 3). The superimposed Trias-

sic–Jurassic terrestrial basins developed on SB and

HHB, in northern Mongolia, consist of Triassic

molasse-like and coal-bearing deposits and trachyan-

desites and Jurassic clastic sediments, which are well

dated by plant fossils. In the Noyon Basin in southern

Mongolia, the Early Triassic Lystrosaurus hedini is

found, which is almost identical to that known from

the Ordos Basin.

Mongolia in the Post-Indosinian

After the Indosinian Orogeny, Mongolia, like the

main parts of China, entered a new stage of intra-

continental development. No marine deposits are

known in Mongolia after the Triassic. Jurassic vol-

cani-sedimentary basins with calc-alkaline volcanics

occur in north-eastern Mongolia, which are the same

as in the adjacent Xingan Mountains region of China.

Cretaceous basins are widely distributed in southern

Mongolia, for example the Zuunbayan Basin near

Sainshand, and contain the renowned Jehol biota of

Early Cretaceous age as in north-eastern China. Ceno-

zoic basins are widespread in western Mongolia. In

the Transaltai Basin situated to the south-east of

Bayanhongor, abundant Palaeogene mammal remains

have been discovered, which may be compared with

those found in Inner Mongolia within China.

Conclusions

The history of China and Mongolia is discussed in

terms of tectonic units and tectonic stages. The crustal

356 CHINA AND MONGOLIA

evolution of China included three megastages in

the Precambrian, marked respectively by the agg-

regation of continental nuclei (2.8 Ga), the lateral

growth and consolidation of proto-platforms throu-

gh the Luliangian Orogeny (1.8 Ga), and the cratoni-

zation and coalescence of platforms into the

Cathaysiana Supercontient through the Jinningian

Orogeny (830 Ma). Until the Jinningian, the crustal

evolution of China seems to have been dominated

by continental growth, consolidation, and conver-

gence to form a part of the Neoproterozoic Rodinia.

In Mongolia, only the last megastage, ending at

830 Ma, marked by the formation of the main

massifs, is recognized.

After the Jinningian, China and Mongolia entered a

megastage characterized by a tectonic pattern consist-

ing of discrete continents and ocean basins, until their

reassembly at the close of the Indosinian Orogeny

(210 Ma). The Cathaysiana Supercontinent began to

dissociate in the Cambrian, and ocean basins were

formed between Sino-Korea and Qaidam, which was

entirely closed through the Caledonian Orogeny, with

marked collision zones. The wide Caledonide be-

tween Yangtze and Cathaysia was, however, folded

and uplifted without clear collision. To the north of

Tarim and Sino-Korea, the narrow Caledonides

represent continent-arc accretion. In Mongolia, the

northern Mongolian massifs were successively ac-

creted to the Siberia Platform, and the Mongolian

massifs, the Salairides and Caledonides, together

formed the northern Mongolian palaeocontinent,

with the Gobi-Altai Caledonian Belt as its southern

margin. Two main branches of Late Palaeozoic

oceans, the Zaysan-South Mongolia-Hingan in the

north, and the Ural-Tianshan in the south, were con-

sumed mainly after the Early Carboniferous, and

are represented respectively by the main Hercynian

sutures (Figure 1). The Late Carboniferous to Early

Triassic marine basins in southern Mongolia and

Inner Mongolia of China probably formed an

ocean with scattered islands that were filled up with-

out appreciable collision. Furthermore, the Late

Hercynides-Indosinides within northern Mongolia

were actually intracontinental residual seas.

To the south of the Kunlun-Qinling central oro-

genic belt of China, an open sea had persisted since

Early Palaeozoic, and the wide Indosinides are

marked by the main Indosinian (Muztagh-Maqen)

convergent zone in the north and the Jinshajiang

zone in the south. The main collision zones usually

coincide with older collision zones; in other words,

they are polyphased or superimposed collision zones.

It was at the close of the Indosinian Stage that the

Laurasia Supercontinent took its final shape as the

northern half of the Permian-Triassic Pangaea.

The post-Indosinian megastage of China and

Mongolia witnessed an entirely new tectonic regime

in East Asia, due to the appearance of the Circum-

Pacific domain as a result of Pangaea disintegration

and the opening of the Atlantic. The subduction of

the western Pacific beneath East Asia in the Jurassic

caused a continent marginal magmatism along east-

ern China, including the Hingan belt and eastern

Mongolia. This new pattern brought about an

apparent change of contrast between northern and

southern China to that between eastern and western

China. In eastern China, and to a certain extent in

eastern Mongolia, there occurred a combination of

continental margin type and intracontinental type of

volcanism, which was followed by the Late Cret-

aceous to Cenozoic tensional regime of rifted basins

and consequent crustal and lithospheric thinning. In

western China, the tectonic process in the Qinghai-

Tibet Plateau consisted of the northward accretion of

the Gondwanan massifs to Eurasia, characterized by

the northward subduction of the Himalaya beneath

Gangise in the south, the distributed crustal thicken-

ing and shortening in the middle, and the southward

indentation from Tarim and Mongol-Siberia in the

northern part. The contrast between the compres-

sional versus extensional, and between the crustal

and lithospheric thickening versus thinning regimes

between western China and eastern China are evi-

dent. These features may have reflected and induced

the deeper process of an eastward flow of the as-

thenosphere from under western China, which might

have, in turn, caused mantle upwelling and crustal

and lithospheric thinning in eastern China.

See Also

Asia: Central; South-East. Gondwanaland and Gon-

dwana. Indian Subcontinent. Japan. Pangaea. Russia.

Further Reading

Badarch G, Cunningham WD, and Windley BF (2002)

A new terrane subdivision for Monglia: implications for

the Phanerozoic crustal growth of Central Asia. Journal

of Asian Earth Sciences 21: 87–110.

Deng JF, Zhao Hailing, Mo Xuanxue, Wu Zongxu, and

Luo Zhaohua (1996) Continental roots-plume tectonics

of China: key to the continental dynamics. Beijing:

Geological Publishing House. (In Chinese with English

abstract.)

Dewey JF, Shackelton RM, Chang C, and Sun W (1994)

The tectonic evolution of the Tibetan Plateau. Philosoph-

ical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Ser. A

327: 379–413.

He Guoqi, Li Maosong, Liu Dequan, Tang Yanling, and

Zhou Ruhong (1988) Palaeozoic Crustal Evolution and

CHINA AND MONGOLIA 357

Mineralization in Xinjiang of China. Urumqi: Xinjiang

People’s Publishing House and Educational and Cultural

Press Ltd. (In Chinese with English abstract.)

Huang TK (1978) An outline of the tectonic characteristics

of China. Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae 71(3): 811–635.

Li Chunyu, Wang Quan, Liu Xueya, and Tang Yaoqijng

(1982) Explanatory Notes to the Tectonic Map of Asia.

Beijing: Cartographic Publishing House.

Liu Baojun and Xu Xiaosong (eds.) (1994) Atlas of

the Lithofacies and Palaeogeography of South China

(Sinian-Triassic). Beijing, New York: Science Press.

Ma Lifang, Qiao Xiufu, Min Longrui, Fan Benxian, and

Ding Xiaozhong (2002) Geological Atlas of China.

Beijing: Geological Publishing House. (61 maps and ex-

planations.)

Ren Jishun, Wang Zuoxun, Chen Bingwei, Jiang Chunfa,

Niu Baogui, Li Jingyi, Xie Guanglian, He Zhengchun,

and Liu Zhigang (1999) The Tectonics of China from a

Global View-A Guide to the Tectonic Map of China and

Adjacent Regions. Beijing: Geological Publishing House.

Shi Xiaoying, Yin Jiaren, and Jia Caiping (1996) Mesozoic

and Cenozoic sequence stratigraphy and sea level change

cycles in the Northern Himalayas, South Tibet, China.

Newsletters on Stratigraphy 33(1): 15–61.

Tomurtogoo O (ed.) (1998–1999) Geological Map of Mon-

golia (1:1 000 000) and Attached Summary. Mongolia:

Ulanbaatar.

Wang Hongzhen (Chief Compiler) (1985) Atlas of

the Palaeogeography of China. Beijing: Cartographic

Publishing House. (143 maps, explanations in Chinese

and English.)

Wang Hongzhen and Mo Xuanxue (1995) An outline of the

tectonic evolution of China. Episodes 18(1–2): 6–16.

Wang Hongzhen and Zhang Shihong (2002) Tectonic

pattern of the world Precambriam basement and problem

of paleocontinent reconstruction. Earth Science – Journal

of China University of Geosciences 27(5): 467–481.

(In Chinese with English abstract.)

Xiao Xuchang, Li Tingdong, Li Guangcen, Chang Chengfa,

and Yuan Xuecheng (1988) Tectonic Evolution of the

Lithosphere of the Himalayas. Beijing: Geological pub-

lishing House. (In Chinese with English abstract.)

Yin A and Harrison TM (2000) Geologic evolution of the

Himalaya-Tibetan Orogen. Annual Review of Earth and

Planetary Sciences 28: 211–280.

Zhang Guowei, Meng Qingren, and Lai Shaocong (1995)

Tectonics and structure of Qinling orogenic belt. Science

in China, Ser. B 38(11): 1379–1394.

Zhong Dalai, et al. (2000) Paleotethysides in West Yunnan

and Sichuan, China. Beijing, New York: Science Press.

Zonenshain LP, Kuzmin ML, and Natapov LM (1990)

Geology of USSR: A Plate-Tectonic Synthesis. Geody-

namic Series 21. Washington, DC: American Geophysical

Union.

a0005 CLAY MINERALS

J M Huggett, Petroclays, Ashtead, UK and The

Natural History Museum, London, UK

ß 2005, Elsevier Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

Clay minerals are a diverse group of hydrous layer

aluminosilicates that constitute the greater part of the

phyllosilicate family of minerals. They are commonly

defined by geologists as hydrous layer aluminosili-

cates with a particle size <2 mm, while engineers and

soil scientists define clay as any mineral particle

<4 mm(see Soils: Modern). However, clay minerals

are commonly >2 mm, or even 4 mm in at least one

dimension. Their small size and large ratio of surface

area to volume gives clay minerals a set of unique

properties, including high cation exchange capacities,

catalytic properties, and plastic behaviour when

moist (see Analytical Methods: Mineral Analysis).

Clay minerals are the major constituent of fine-

grained sediments and rocks (mudrocks, shales, clays-

tones, clayey siltstones, clayey oozes, and argillites).

They are an important constituent of soils, lake, estu-

arine, delta, and the ocean sediments that cover most

of the Earth’s surface. They are also present in almost

all sedimentary rocks, the outcrops of which cover

approximately 75% of the Earth’s land surface. Clays

which form in soils or through weathering principally

reflect climate, drainage, and rock type (see

Weathering; Palaeoclimates). It is now recognized

that re-deposition as mudrock only infrequently pre-

serves these assemblages, and clay assemblages in

ocean sediments should not be interpreted in terms

of climate alone, as has been done in the past. Most

clay in sediments and sedimentary rocks is, in fact,

reworked from older clay-bearing sediments, and

many are metastable at the Earth’s surface. This does

not preclude the use of clays in stratigraphic correl-

ation, indeed it can be a used in provenance studies.

A few clays, notable the iron-rich clays form at the

Earth’s surface either by transformation of pre-

existing clays or from solution. These clays are useful

environmental indicators, so long as they are not

reworked.

358 CLAY MINERALS

Clay Structure and Chemistry

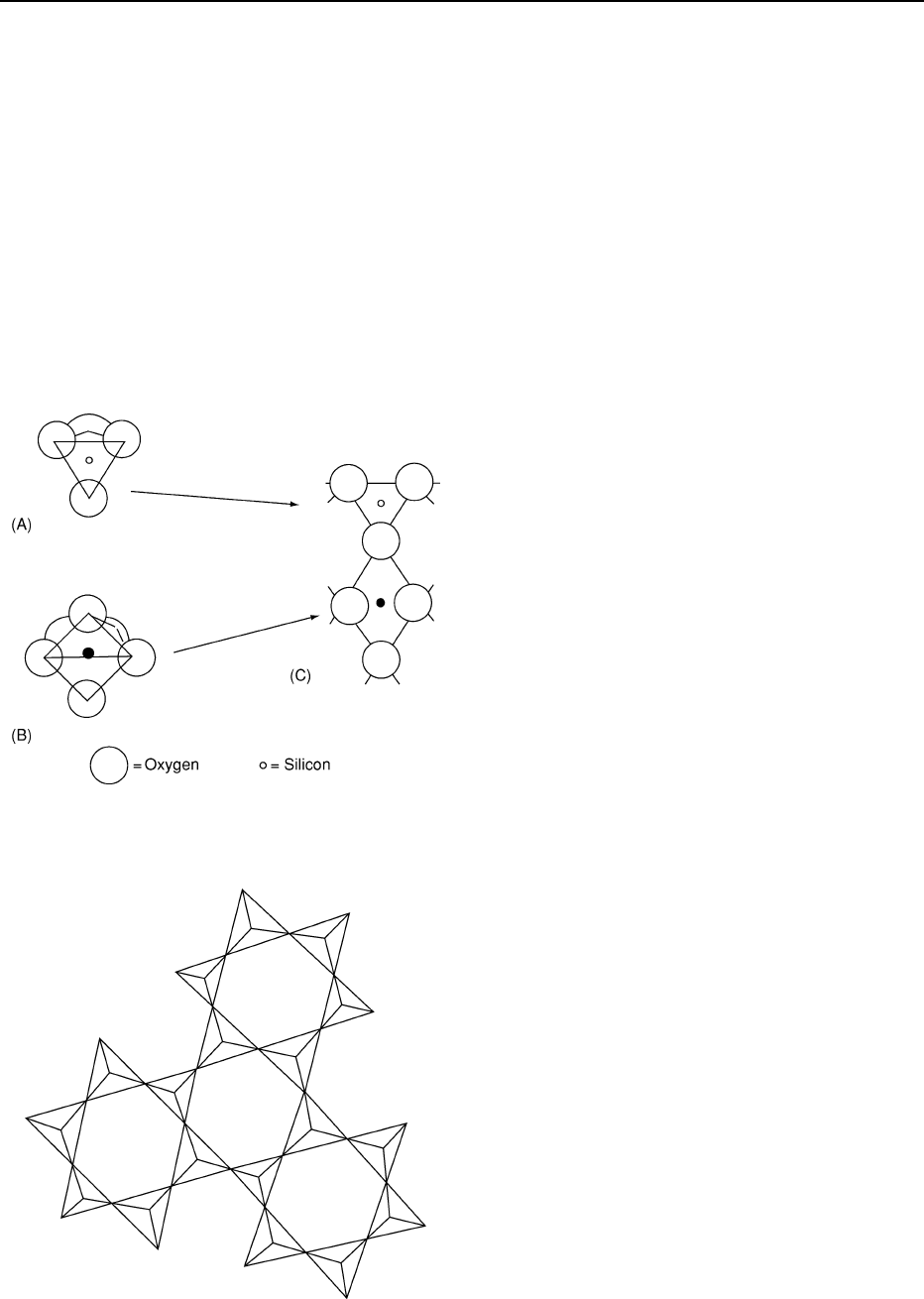

Clays can be envisaged as comprising sheets of tetra-

hedra and sheets of octahedra (Figure 1). The general

formula for the tetrahedra is T

2

O

5

, where T is mainly

Si

4

, but Al

3þ

frequently (and Fe

3þ

less frequently)

substitutes for it. The tetrahedra have a hexagonal

arrangement, if not distorted by substituting cations

(Figure 2). The octahedral sheet comprises two planes

of close-packed oxygen ions with cations occupying

the resulting octahedral sites between the two planes

(Figure 1B). The cations are most commonly Al

3þ

,

Fe

3þ

,andMg

2þ

, but the cations of other transition

elements can occur. The composite layer formed by

linking one tetrahedral and one octahedral sheet is

known as a 1:1 layer. In such layers, the upper-most

unshared plane of anions in the octahedral sheet con-

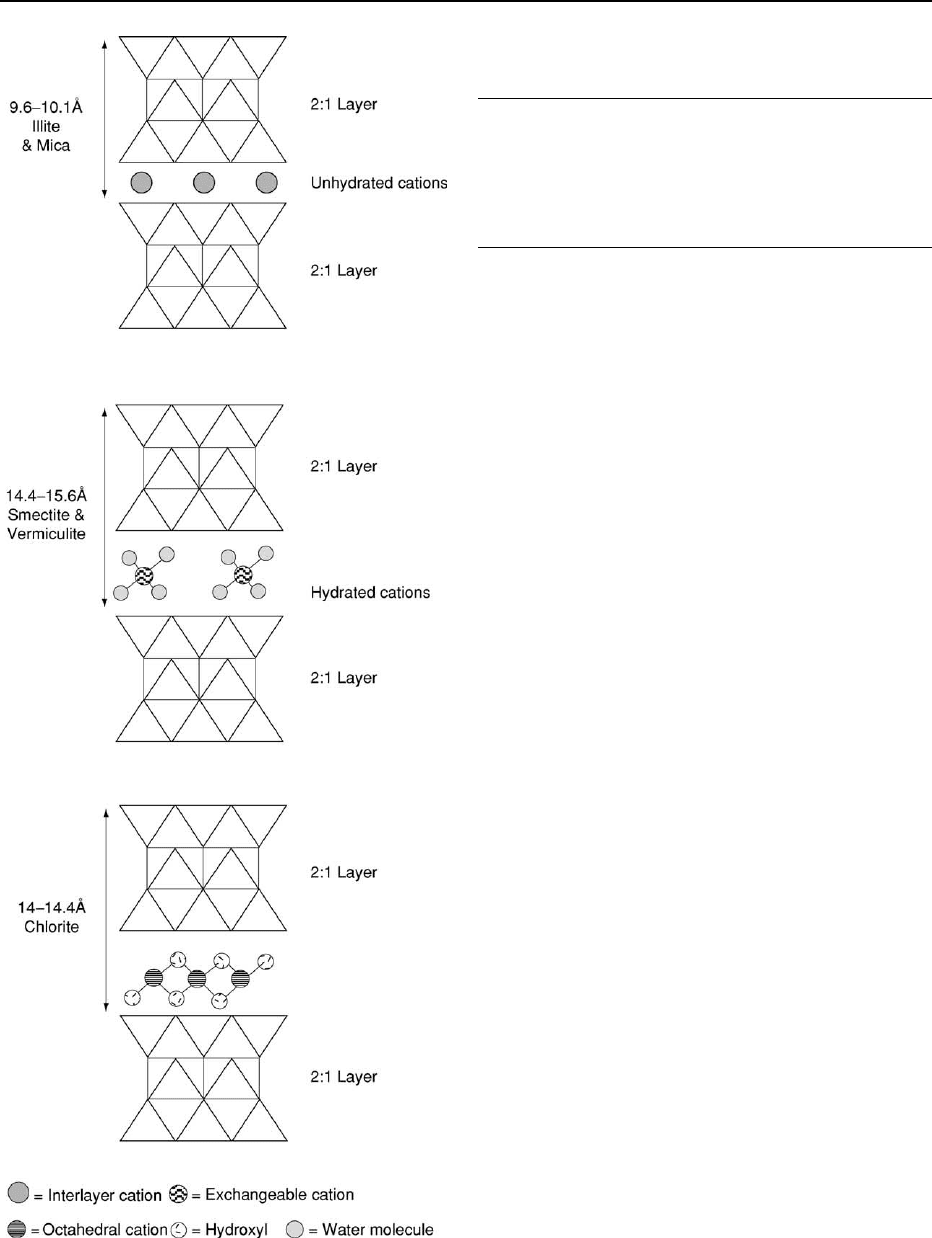

sists entirely of OH groups. A composite layer of one

octahedral layer sandwiched between two tetrahedral

layers (both with the tetrahedra pointing towards the

octahedral layer) is known as a 2:1 layer. 2:1 clays of

the mica and chlorite families have multiple polytypes

defined by differences in stacking parallel to the c axis.

If the 1:1 or 2:1 layers are not electrostatically neutral

(due to substitution of trivalent cations for Si

4c

or

of divalent for trivalent cations) the layer charge is

neutralized by interlayer materials. These can be ca-

tions (most commonly K

þ

,Na

þ

,orNH

þ

4

), hydrated

cations (most commonly Mg

2þ

,Ca

2þ

,orNa

þ

) or sin-

gle sheets of hydroxide octahedral groups (Al(OH)

3

or

Mg(OH)

2

(Figure 3). These categories approximately

coincide with the illite, smectite, and chlorite-

vermiculite families of clays. It is evident that the

different types of interlayer cation will have a direct

affect upon the thickness of the clay unit cell in the 001

dimension. This property, together with the ease with

which the interlayer cations are hydrated or will inter-

act with organic compounds, is much used in X-ray

diffraction to identify clay mineral.

The principal clay physical properties of interest to

the geologist are cation exchange capacity and inter-

action with water. Clays have charges on (001) layer

surfaces and at unsatisfied bond edge sites. An im-

portant consequence of these charges is that ions and

molecules, most commonly water, are attracted to and

weakly bonded to clay mineral particles. In most cases

cations are attracted to layer surfaces and anions to

edge sites. If the interlayer charge is low, cations be-

tween 1:1 layers can be exchanged for other cations

and these cations can be hydrated by up to two water

layers. Water in the interlayer site is controlled by

several factors including the cation size and charge.

In ‘normal’ pore fluid, one layer of water is associated

with monovalent cations, two layers with divalent

cations. Water can also weakly bond to the outer

surface of clay particles. The relative ease with which

one cation will replace another is usually:

Na

þ

< K

þ

< Ca

2þ

< Mg

2þ

< NH

þ

4

i.e., NH

þ

4

is usually more strongly fixed in the inter-

layer sites than is Na

þ

. The exchangeability of cations

is measured as the cation exchange capacity (CEC).

This technique is used to characterise clay reactivity,

and each clay mineral has a characteristic range of

CEC values (Table 1).

Classification

Clays are normally classified according to their layer

type, with layer charge used to define subdivisions

Figure 1 (A) Tetrahedrally co-ordinated cation polyhedrons;

(B) octahedrally co-ordinated cation polyhedrons; (C) linked

octahedral and tetrahedral polyhedrons.

Figure 2 Hexagonal arrangement of edge-linked tetrahedra.

CLAY MINERALS 359

(Table 2). Because of their fine particle size, clay

minerals are not easily identified by optical methods,

though the distinctive chemistry (and sometimes

habit or morphology) of most allows identification

by X-ray analysis in electron microscope studies. The

most reliable method of clay identification, particu-

larly in very fine grained rocks is X-ray diffraction,

either of the bulk sample, or more reliably, of the fine

fraction (usually <2 mm). The response of the clays to

glycol or glycerol solvation, cation saturation, and

heat treatment is used to determine which clays are

present and the extent of any interlayering (see Ana-

lytical Methods: Mineral Analysis).

Clays (Serpentine and Kaolin) (1:1)

Berthierine, (FeMg)

3

-x(Fe

3

Al)x(Si

2-x

Al

x

)O

5

(OH)

4

,is

the FeII-rich member of the serpentine subgroup most

commonly encountered in unmetamoprhosed sedi-

mentary rocks and odinite is its FeIII-rich counterpart

found (so far) in Eocene and younger sediments.

Chemically, the kandite minerals are alumina octahe-

dra and silica tetrahedra with occasional substitution

of Fe

3þ

for Al

3þ

. Of the kandite group, kaolinite is by

far the most abundant clay. Kaolinite and both hal-

loysites are single-layer structures whereas dickite

and nacrite are double layer polytypes, i.e., the repeat

distance along the direction perpendicular to (001)

is 14 A

˚

, not 7 A

˚

. Dickite and nacrite were originally

distinguished from kaolinite on the basis of XRD

data, however this is seldom easy, especially in the

presence of feldspar and quartz. Infra-red and differ-

ential thermal analysis can be successfully used to

make the distinction between these two clays.

Clays (Talc and Pyrophyllite) (2:1)

Ideal talc (Mg

3

Si

4

O

10

(OH)

2

) and pyrophyllite

(Al

2

Si

4

O

10

(OH)

2

) are 2:1 clays with no substitution

in either sheet and hence no layer charge or interlayer

cations. However, minor substitution is common.

Figure 3 2:1 Clay structures.

Table 1 Typical values for cation exchange capacities. Cation

exchange capacities (CEC) in milliequivalents/gram. (Data from

multiple sources.)

meq/100 g

Kaolinite 3 to 18

Halloysite 5 to 40

Chlorite 10 to 40

Illite 10 to 40

Montmorillonite 60 to 150

Vermiculite 100 to 215

360 CLAY MINERALS

Clays (Smectite) (2:1)

The 2:1 clays with the lowest interlayer charge are the

smectites. This group have the capacity to expand and

contract with the addition or loss (through heating) of

water and some organic molecules. It is this property

that is used to identify smectites by glycol or glycerol

solvation and heat treatments in XRD studies. This

swelling is believed to be due to the greater attraction

of the interlayer cations to water than to the weakly

charged layer. Montmorillonite is a predominantly di-

octahedral smectite with the charge primarily in the

octahedral sheet (R

þ

(Al

3

Mg

.33

)Si

4

O

10

(OH)

2

), while

beidellite (R

þ

Al

2

(Si

3.67

Al

.33

)O

10

(OH)

2

) and nontro-

nite (R

þ

Fe(III)

2

(Si

3.67

Al

.33

)O

10

(OH)

2

) are dioctahe-

dral with the charge mainly in the tetrahedral sheet

(where R ¼ mono or divalent interlayer cations).

Hectorite is a rare clay, similar to montmorillonite

but it is predominantly trioctahedral with Mg

2þ

and

Li

2þ

in the octahedral layer. Saponite is another un-

common smectite with a positive charge on the octa-

hedral sheet and a negative one on the tetrahedral

sheet. In smectite the interlayer cations are typically

Ca

2þ

,Mg

2þ

,orNa

þ

; in high charge smectites K

þ

may

be present. When smectite expands, the interlayer

cation can be replaced by some other cation. Hence

the cation exchange capacities of smectite is high

compared with nonexpanding clay minerals. CEC

can therefore be used to identify smectite.

Clays (Vermiculite) (2:1)

The second group of clays with exchangeable cations

is vermiculite. Vermiculite has a talc-like structure in

which some Fe

3þ

has been substituted for Mg

2þ

and

some Al

3þ

for Si

4þ

, with the resulting charge balanced

by hydrated interlayer cations, most commonly

Mg

2þ

. The layer charge typically ranges from 0.6 to

0.9. Vermiculite is distinguished from smectite by

XRD after saturating with MgCl

2

and solvation with

glycerol. This results in expansion of the interlayer to

14.5 A

˚

, rather than the 18 A

˚

characteristic of smectite

(though there may be exceptions to this rule). Ver-

miculite is much less often encountered in sedimentary

rocks than is smectite, probably because it is most

commonly a soil-formed clay, while coarsely crystal-

line vermiculite deposits are formed from alteration of

igneous rocks.

Clays (Mica and Illite) (2:1)

Substitution of one Al

3þ

for one Si

4þ

results in a layer

charge of 1, which in true mica is balanced by one

monovalent interlayer cation (denoted R). In mica the

cation is usually K

þ

, less often Na

þ

or Ca

2þ

and rarely

NH

þ

. The term clay grade mica is sometimes used to

describe mica which has been weathered resulting in

loss of interlayer cations or formation of expandable

smectite layers. 2:1 clays with layer charge 0.8 are

illite (R

þ

(Al

2-x

Mg, Fe II, Fe III)

x

Si

4-y

Al

y

O

10

(OH)

2

)

and glauconite (the ferric iron-rich equivalent of

illite). Like mica, illite and glauconite are character-

ised by a basal lattice spacing of d(001) ¼ 10 A

˚

which is

unaffected by glycol or glycerol solvation, nor by heat-

ing. Illite is used as both a specific mineral term and as

a term for a group of similar clays, including some

with a small degree of mixed layering. Illite has been

described as detrital clay-grade muscovite of the 2 M

Table 2 Clay classification by layer type Tr ¼ trioctahedral, Di ¼ dioctahedral, x ¼ layer charge, Note the list of species is not

exhaustive, and interstratified mixed-layer clays abound (see below). (Adapted from Brindley and Brown, 1980.)

Layer

type Group Sub-group Species (clays only)

1:1 Serpentine-kaolin

(x 0)

Serpentines (Tr) Berthierine, odinite

Kandites (di) Kaolinite, dickite, 7 A

˚

&10A

˚

halloysite, nacrite

2:1 Talc-pyrophyllite (x 0) Talc (Tr) pyrophyllite (Di)

2:1 Smectite (x 0.2–0.6) Tr smectites Montmorillonite, hectorite, saponite beidellite, nontronite

Di smectites

2:1 Vermiculite (x 0.6–0.9) Tr vermiculites

Di vermiculites

2:1 Mica-illite (x 0.8) Tr illite?

Di illite Illite, glauconite

2:1 Chlorite (x variable) Tr-Tr chlorites Chamosite, clinochlore, ripidolite etc donbassite

Di-Di chlorites

Tr-Di chlorites

Di-Tr chlorites Sudoite, cookeite

2:1 Sepiolite-palygorskite

(x variable)

Sepiolites

palygorskites

Sepiolite

palygorskite (syn. attapulgite)

CLAY MINERALS 361

polytype, plus true 1 Md and 1 M illite polytypes (with

or without some smectite or chlorite mixed layers).

Illite is, however, chemically distinct from muscovite

in having less octahedral Al, less interlayer K and more

Si, Mg, and H

2

O.

Clays (Chlorite) (2:1)

Chlorite consists of a 2:1 layer with a negative charge

[(R

2þ,

R

2þ

)

3

(

x

Si

4x

R

2þ

y

)O

10

OH

2

]

that is balanced by

a positively charged interlayer octahedral sheet

[(R

2þ,

R

3þ

)

3

(OH)

6

]

þ

. R is most commonly Mg, Fe II,

and Fe III, with Mg-rich chlorite (clinochlore) gener-

ally being metamorphic (high temperature) or associ-

ated with aeolian and sabkha sediments, while Fe-rich

chlorite (chamosite) is typically diagenetic (low tem-

perature). Ni-rich chlorite (nimite) and Mn-rich chlor-

ite (pennantite) are the other two less common

principal varieties of chlorite. Most chlorites are trioc-

tahedral in both sheets, i.e., the ferric iron content is

low. Chlorites with dioctahedral 2:1 layers and trioc-

tahedral interlayer sheets are called ditrioctahedral

chlorite (the reverse, tri-dioctahedral chlorite is un-

known). Chlorite classification is further complicated

by the existence of different stacking polytypes.

Mixed layer clays are those which consist of discrete

crystals of interlayered clays, usually just two clay

species are present, though three is known, mainly

from soils. The stacking can be random, partially

regular, or regular. Different types of ordering are

described using the Reichweite terminology (Reich-

weite means ‘the reach back’), denoted as R0 for

random mixed layering, R1 for regular alternating

layers of two clay types (also called rectorite), and

R3 for ABAA for regularly stacked sequences. R2

(ABA) has not been positively identified. The most

frequently encountered mixed layer clay is illite-

smectite because smectite is progressively replaced

by illite during deep burial diagenesis, mostly in

mudrock. This clay is probably more abundant than

either illite or smectite. Interstratified chlorite-smec-

tite is associated with alteration of basic igneous

rock or rock fragments in sandstone. Regularly inter-

stratified chlorite-smectite and chlorite-vermiculite

with 50% of each component are both known as

corrensite. 14A

˚

chlorite interstratified with 7A

˚

chlorite is becoming a more widely recognised clay,

particularly in sandstones which have undergone

some diagenesis.

Fibrous Clays (Sepiolite and Palygorskite) (2:1)

Sepiolite and palygorskite (also known as attapulgite)

are structurally different from other clays in two

ways. Firstly, the tetrahedral sheets are divided into

ribbons by inversion though they are still bonded in

sheet form, and secondly the octahedral sheets are

continuous in two dimensions only. They are conse-

quently fibrous, though their macroscopic form may

be flakes or fibres. An ideal sepiolite formula is ap-

proximately Mg

8

Si

12

O

30

OH

4

(OH

2

)

4

X[R

2þ,

(H

2

O)

8

],

and palygorskite is MgAlS

8

O

20

OH

3

(OH

2

)

4

X[R

2þ,

(H

2

O)

4

]. Where X ¼ octahedral sites in sepio-

lite which may contain Al, Fe, Mn, or Ni, while in

palygorskite may be present Na, Fe, and Mn. Cation

exchange capacities are intermediate between nonex-

panding and expanding 2:1 clays, and the fibrous clay

structure does not swell with addition of either water

or organic solvents.

Clay Formation Through Weathering

and Neoformation in Soils

Most of the clay in sedimentary rocks is probably

formed by weathering or in soils. However, it is im-

portant to realize that firstly the amount of neoformed

clay in soils is, at any one time, small relative to the

total clay in sediments and sedimentary rocks and

secondly that most clay in sediments is derived

through reworking of older clay-rich sediment. Clay

assemblages resulting from weathering reflect the ped-

oclimatic conditions (temperature, precipitation,

drainage, vegetation), the composition of the rock

being weathered and the length of time during which

weathering occurs. This applies to palaeosols as well

as recent soils (see Soils: Palaeosols), if they can be

shown to be unaffected by clay diagenesis. principal

process involved is hydrolysis, hence the degree of

weathering increases with temperature and extent of

exposure to water (precipitation and drainage),

though plants and micro-organisms may also

be important weathering agents (see Weathering). In

tectonically unstable areas, rapid weathering and ero-

sion may prevent formation of a stable soil clay assem-

blage. In general, very cold or hot and dry climate

results in illite and chlorite formation. Temperate cli-

mates are characterised by illite, irregular mixed

layers, vermiculite, and smectite (generally beidellite

in soils, montmorillonite in altered tuff beds). Fe

smectite and fibrous clays (usually palygorskite)

prevail in subarid climates and hot wet climates

are characterized by kaolinite (and the iron oxy-

hydroxide goethite). If soil-formed clays are preserved

without further modification, either in the soil, during

transport, or diagenesis, they may be preserved as

palaeoclimatic indicators. Such preservation is, how-

ever, less common and less easily distinguished from

diagenetic clays or clays reworked from older sedi-

mentary rocks, than was formerly thought. These

three modes of origin may be identified by careful

provenance and petrographic studies.

362 CLAY MINERALS