Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 1: To 1800

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

AN EXCHANGE OF ROYAL CORRESPONDENCE

In 1681, King Louis XIV of France wrote a letter to

the ‘‘king of Tonkin’’ (the Trinh family head, then

acting as viceroy to the Vietnamese ruler) request-

ing permission for Christian missionaries to prose-

lytize in Vietnam. The latter politely declined the request on the

grounds that such activity was prohibited by ancient custom.

In fact, Christian missionaries had been active in Vietnam for

years, and their intervention in local politics had aroused the

anger of the court in Hanoi.

A Letter to the King of Tonkin from Louis XIV

Most high, most excellent, most mighty, and most magnanimous

Prince, our very dear and good friend, may it please God to increase

your greatness with a happy end!

We hear from our subjects who were in your Realm what pro-

tection you accorded them. We appreciate this all the more since

we have for you all the esteem that one can have for a prince as il-

lustrious through his military valor as he is commendable for the

justice which he exercises in his Realm. We have even been in-

formed that you have not been satisfied to extend this general

protection to our subjects but, in par ticular, that you gave effec-

tive proofs of it to Messrs. Deydier and de Bourges. We would

have w ished that they m ight have been able to recognize all the

favors they received from you by having presents worthy of you

offered you; but since the war which we have had for several

years, in which all of Europe had banded together against us, p re-

vented our vessels from going to the Indies, at the present time,

when we are at peace after having gain ed many v ictories and ex-

panded our Realm through the conquest of several impor tant

places, we have immediately given orders to the Royal Company

to establish itself in your kingdom as soon as possible, and have

commanded Messrs. Deydier and de Bourges to remain with you

in order to m aintain a good relationship between our su bjects and

yours, also to warn us on occasions that might present themselves

when we might be able to give you proofs of our esteem and of

our w ish to concur w ith your satisfaction as well as with your best

interests.

By way of initial proof, we have given orders to have brought

to you some presents which we believe might be agreeable to you.

But the one thing in the world which we desire most, both for you

and for your Realm, would be to obtain for your subjects who have

already embraced the law of the only true God of heaven and earth,

the freedom to profess it, since this law is the highest, the noblest,

the most sacred, and especially the most suitable to have kings reign

absolutely over the people.

We are even quite convinced that, if you knew the truths and

the maxims which it teaches, you would give first of all to your sub-

jects the glorious example of embracing it. We wish you this incom-

parable blessing together w ith a long and happy reign, and we pray

God that it may please Him to augment your greatness with the

happiest of endings.

Written at Saint-Germain-en-Laye, the 10th day of

January, 1681,

Your very dear and good friend,

Louis

Answer from the King of Tonkin to Louis XIV

The King of Tonkin sends to the King of France a letter to express

to him his best sentiments, saying that he was happy to learn that

fidelity is a durable good of man and that justice is the most im-

portant of things. Consequently practicing of fidelity and justice

cannot but yield good results. Indeed, though France and our

Kingdom differ as to mountain s, rivers, and boundaries, if fidelity

and justice reign among our v illages, our conduct w ill express all

of our good feelings and contain precious gifts. Your communica-

tion, which comes from a country which is a thousand leagues

away, and which proceeds fr om the heart as a testimony of your

sincerity, merits repeated consideration and infinite praise. Polite-

ness toward strangers is nothing un usual in our countr y. There is

not a stranger who is n ot well received by us. How then could we

refuse a man from France, which is the most celebrated among

the kingdoms of the world and which for love of us w ishes to fre-

quent us and bring us merchandise? These feelings of fidelity and

justice are truly worthy to be applauded. As regards your wish

that we should cooperate in propagating your religion, we do not

dare to permit it, for there is an ancient custom, introduced by

edicts, which formally for bids it. Now, edicts are promulgated

only to be carried out faithfully ; w ithout fidelity nothing is stable.

How could we disdain a well-established custom to satisfy a pri-

vate friendship? ...

We beg you to understand well that this is our communication

concerning our mutual acquaintance. This then is my letter. We

send you herewith a modest gift, which we offer you with a glad

heart.

This letter was written at the beginning of winter and on a

beautiful day.

Q

Compare the king of Tonkin’s response to Louis XIV with

the answer that the Mongol emperor Kuyuk Khan gave to the

pope in 1244 (see p. 249). Which do you think was more

conciliatory?

354 CHAPTER 14 NEW ENCOUNTERS: THE CREATION OF A WORLD MARKET

navigable rivers. In part, this was because agriculture itself

was becoming more commercialized as cash crops like

sugar and spices replaced subsistence farming in rice or

other cereals in some areas.

Regional and interregional trade were already ex-

panding before the coming of the Europeans. The central

geographic location of Southeast Asia enabled it to be-

come a focal point in a widespread trading network.

Spices, of course, were the mainstay of the interregional

trade, but Southeast Asia exchanged other products as

well. The region exported tin (mined in Malaya since the

tenth century), copper, gold, tropical fruits and other

agricultural products, cloth, gems, and luxury goods in

exchange for manufactured goods, ceramics, and high-

quality textiles such as silk from China.

Society

In general, Southeast Asians probably enjoyed a some-

what higher living standard than most of their

contemporaries elsewhere in Asia. Although most of the

population was poor by modern Western standards,

hunger was not a widespread problem. Several factors

help explain this relative prosperity. In the first place,

most of Southeast Asia has been blessed by a salubrious

climate. The uniformly high temperatures and the

abundant rainfall enable as many as two or even three

crops to be grown each year. Second, although the soil in

some areas is poor, the alluvial deltas on the mainland are

fertile, and the volcanoes of Indonesia periodically spew

forth rich volcanic ash that renews the mineral resources

of the soil of Sumatra and Java. Finally, with some ex-

ceptions, most of Southeast Asia was relatively thinly

populated.

Social institutions tended to be fairly homogeneous

throughout Southeast Asia. Compared with China and

India, there was little social stratification, and the nuclear

family predominated. In general, women fared better in

the region than anywhere else in Asia. Daughters often

had the same inheritance rights as sons, and family

property was held jointly between husband and wife.

Wives were often permitted to divorce their husbands,

CHRONOLOGY

The Spice Trade

Vasco da Gama lands at Calicut in

southwestern India

1498

Albuquerque establishes base at Goa 1510

Portuguese seize Malacca 1511

Portuguese ships land in southern China 1514

Magellan’s voyage around the world 1519--1522

English East India Company established 1600

Dutch East India Company established 1602

English arrive at Surat in northwestern India 1608

Dutch fort established at Batavia 1619

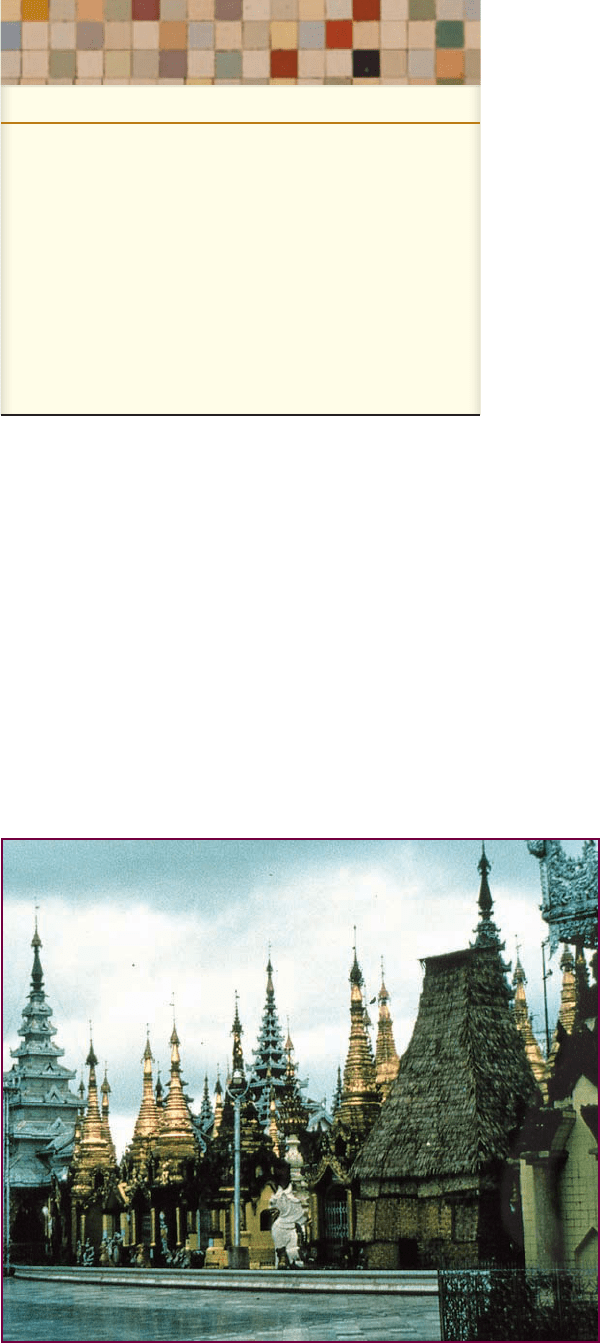

In a Buddhist Wonde rland. The Shwedagon Pagoda

is the most sacred site in Myanmar (Burma). Located on

a hill in today’s capital of Yangon (formerly Rangoon),

the pagoda was originally erected on the site of an earlier

Buddhist structure sometime in the late first millennium

C.E. Its centerpiece is a magnificent stupa covered in gold

leaf that stands more than 320 feet high. The platform at

the base of the stupa contains a multitude of smaller

shrines and stupas covered with marble carvings and

fragments of cut glass. It is no surprise that for centuries,

the Buddhist faithful have visited the site, and the funds

they have donated have made the Shwedagon stupa one

of the wonders of the world.

c

William J. Duiker

SOUTHEAST ASIA IN THE ERA OF THE SPICE TRADE 355

OPPOSING VIEWPOINTS

T

HE MARCH OF CIVILIZATION

As Europeans began to explore new parts of the

world beginning in the fifteenth century, they were

convinced that it was their duty to introduce civi-

lized ways to the heathen peoples of Asia, Africa,

and the Americas. Such was the message of Spanish captain

Vasco N

u

~

nez one September morning in 1513, when from a hill

on the Isthmus of Panama he first laid eyes on the Pacific

Ocean. Two centuries later, however, the intrepid British ex-

plorer James Cook, during his last visit to the island of Tahiti in

1777, expressed in his private journal his growing doubts that

Europeans had brought lasting benefits to the Polynesian

islanders. Such disagreements over the alleged benefits of

Western civilization to non-Western peoples would continue to

spark debate during the centuries that followed and remain with

us today (see the comparative essay ‘‘Imperialism: The Balance

Sheet’’ in Chapter 21).

Gonzalo Fern

andez de Ov ieda, Historia General

y Natural de las Indias

On Tuesday, the twe nty-fifth of September of the year 1513, at

ten o’clock in the morning, Captain Vasco N

u

~

nez, havi ng gone

ahead of his company, climbe d a hill w ith a bare summit, and

from the top of this hill saw the South Sea. Of all the Christians

in his company, he was the first to see it. He turned back toward

his peop le, ful l of joy, lifting his ha nds and his eyes to Heaven,

praising Jesus Christ and his glorious Mother the Virgin, Our

Lady. Then he fell upon his knees on the ground and gave great

thanks to God for the mercy He had shown him, in allowing him

to discover that sea, and thereby to render so great a service to

GodandtothemostsereneCatholicKingsofCastile,our

sovereigns. ...

And he told all the people with him to kneel also, to give the

same thanks to God, and to beg Him fervently to allow them to

see and discover the secrets and great riches of that sea and coast,

for the greater glory and increase of the Christian faith, for the

conversion of the Indians, natives of those southern regions, and

for the fame and prosperity of the royal throne of Castile and of

its sovereigns present and to come. All the people cheerfully and

willingly did as they were bidden; and the Captain made them fell

a big tree and make from it a tall cross, which they erected in that

same place, at the top of the hill from which the South Sea had

first been seen. And they all sang together the hymn of the glori-

ous holy fathers of the Church, Ambrose and Augustine, led by a

devout priest Andr

es de Vera, who was with them, saying with

tears of joyful devotion Te Deum laudamus, Te Dominum

confitemur.

Journal of Captain James Cook

I cannot avoid expressing it as my real opinion that it would have

been far better for these poor people never to have known our su-

periority in the accommodations and arts that make life comfort-

able, than after once knowing it, to be again left and abandoned

in their original incapacity of improvement. Indeed they cannot

be restored to that happy mediocrit y in which they lived before

we discovered them, if the intercourse between us should be dis-

continued. It seems to me that it has become, in a manner, in-

cumbent on the Europeans to visit them once in three or four

years, in order to supply them w ith those conveniences which we

have introduced among them, and have given them a predilection

for. The want of such occasional supplies will, probably, be felt

very heavily by them, when it may be too late to go back to their

old, less perfect, contrivances, which they now despise, and have

discontinued since the introduction of ours. For, by the time that

the iron tools, of which they are now possessed, are worn out,

they will have almo st lost the knowledge of their own. A stone

hatchet is, at present, as rare a thing amongst them, as an iron

one was eig ht years ago, and a chisel of bone or stone is not

to be seen.

Q

Why does James Cook express regret that the peoples

of Tahiti had been exposed to European influence? How might

Captain N

u

~

nez have responded to Cook?

Maori Tiki god, South Pacific

c

William J. Duiker

356 CHAPTER 14 NEW ENCOUNTERS: THE CREATION OF A WORLD MARKET

and monogamy was the rule rather than the exception.

Although women were usually restricted to specialized

work, such as making ceramics, weaving, or transplanting

the rice seedlings into the main paddy fields, and rarely

possessed legal rights equal to those of men, they enjoyed

a comparatively high degree of freedom and status in

most societies in the region and were sometimes involved

in commerce.

Ocean

Pacific

Ocean

Pacific

Ocean

Indian

Ocean

Atlantic

JAPAN

Bahia

Lisbon

Azores

Slave

Coast

Surat

Bombay

Canton

Macao

Manila

Malacca

Batavia

Potosí

Lima

Cape of Good Hope

CELEBES

SPICE

ISLANDS

BORNEO

SUMATRA

MALAYA

Palembang

JAVA

Goa

Cochin

Pondicherry

Madras

Masulipatam

Calcutta

Delhi

Patna

Cape Town

Mozambique Channel

Fernando Po

Marseilles

Bordeaux

Le Havre

Amsterdam

Hamburg

London

Liverpool

Pernambuco

Rio de Janeiro

São Paulo

Buenos Aires

Cape Horn

Asunción

Valparaiso

Cuzco

Callao

Guayaquil

New

Amsterdam

Cartagena

Panama

PERU

BRAZIL

Trinidad

Leeward Is.

Puerto

Rico

Cuba

Veracruz

Acapulco

Mexico City

New Orleans

Charleston

Philadelphia

Baltimore

Boston

New York

Montreal

Quebec

CANADA

MEXICO

INDIA

RUSSIAN EMPIRE

OTTOMAN

EMPIRE

CHINA

Basra

Cairo

Dakar

Accra

Kilwa

Zanzibar

Sofala

Furs

Fish

Timber

Tobacco

Rice

Trade winds

Silver

Dyestuffs

Gold

Sugar

Cacao

Coffee

Cotton

Diamonds

Hides

Spices

Tea

Silk production

Silk textiles

Cotton textiles

Ivory

0 2,000 4,000 Miles

0 2,000 4,000 6,000 Kilometers

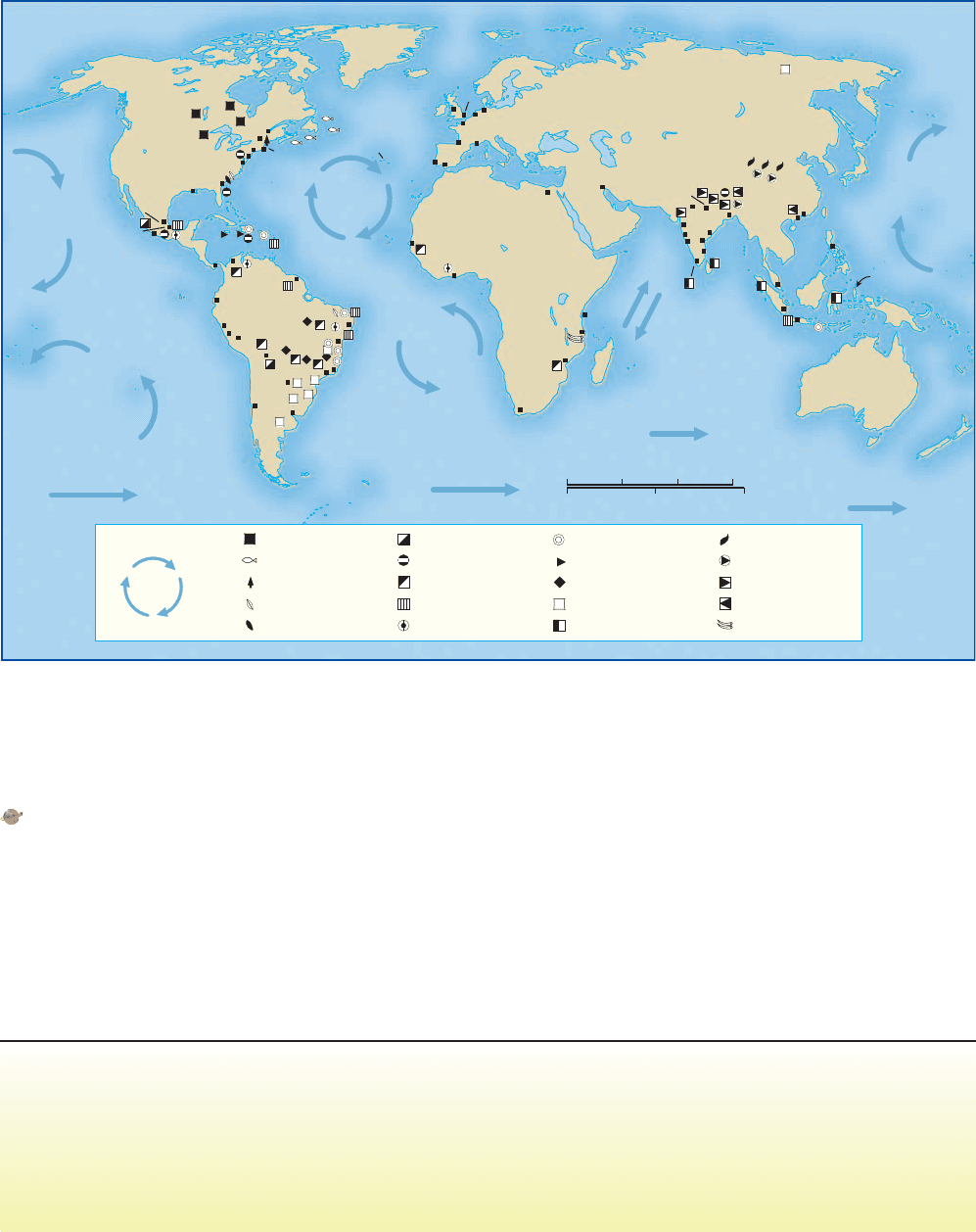

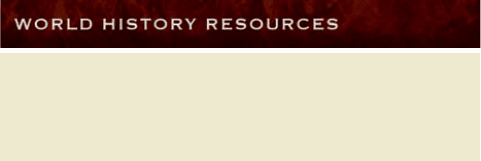

MAP 14.5 The Pattern of World Trade from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth

Centuries.

This map shows the major products that were traded by European merchants

throughout the world during the era of European exploration. Prevailing wind patterns in the

oceans are also shown on the map.

Q

What were the primary sourc es of gold and silver, so sought after by Columbus and

his successors?

View an animated version of this map or related maps at www .c engage.com/history/

duikspiel/essentialworld6e

CONCLUSION

DURING THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY, the pace of interna-

tional commerce increased dramatically. Chinese fleets visited the

Indian Ocean while Muslim traders extended their activities into the

Spice Islands and sub-Saharan West Africa. Then the Europeans

burst onto the world scene. Beginning with the seemingly modest

ventures of the Portuguese ships that sailed southward along the

West African coast, the process accelerated with the epoch-making

voyages of Christopher Columbus to the Americas and Vasco da

Gama to the Indian Ocean in the 1490s. Soon a number of other

European states had entered the scene, and by the end of the

eighteenth century, they had created a global trade network

dominated by Western ships and Western power that distributed

foodstuffs, textile goods, spices, and precious minerals from one

end of the globe to the other (see Map 14.5).

CONCLUSION 357

TIMELINE

1400 1450

1500 1550 1600 1650 17501700

Africa

Southeast

Asia

Americas

Chinese fleets visit

East Africa

Rise of Malacca sultanate

Voyages of Columbus to

the Americas

First voyage around the world

Plantation system develops in Brazil

Portuguese seize Malacca

Ashanti kingdom

established in West Africa

Portuguese expelled

from Mombasa

Pizzaro’s conquest of the InkasSpanish conquest of Mexico

Dutch establish port at Batavia

First boatload of slaves

to the Americas

Bartolomeu Dias sails around

southern tip of Africa

In less than three hundred years, the European Age of

Exploration changed the face of the world. In some areas, such

as the Americas and the Spice Islands, it led to the destruction

of indigenous civilizations and the establishment of European

colonies. In others, as in Africa, South Asia, and mainland

Southeast Asia, it left native regimes intact but had a strong impact

on local societies and regional trade patterns. In some areas, it led to

an irreversible decline in traditional institutions and values, setting

in motion a corrosive process that has not been reversed to this day

(see the box on p. 356).

At the time, many European observers viewed the process in a

favorable light. Not only did it expand world trade and foster the

exchange of new crops and discoveries between the Americas and

the rest of the world, but it also introduced Christianity to ‘‘heathen

peoples’’ around the globe. Many modern historians have been

much more critical, concluding that European activities during the

sixteenth and seventeenth centuries created a ‘‘tributary mode of

production’’ based on European profits from unequal terms of trade

that foreshadowed the exploitative relationship characteristic of the

later colonial period. Other scholars have questioned that conten-

tion, however, and argue that although Western commercial

operations had a significant impact on global trade patterns, they

did not---at least not before the eighteenth century---freeze out non-

European participants. Muslim merchants, for example, were long

able to evade European efforts to eliminate them from the spice

trade, and the trans-Saharan caravan trade was relatively unaffected

by European merchant shipping along the West African coast. In

some cases, the European presence may even have encouraged new

economic activity, as in the Indian subcontinent (see Chapter 16).

By the same token, the Age of Exploration did not, as some

have claimed, usher in an era of Western dominance over the rest of

the world. In the Middle East, powerful empires continued to hold

sway over the lands washed by the Muslim faith. Beyond the

Himalayas, Chinese emperors in their new northern capital of

Beijing retained proud dominion over all the vast territory of

continental East Asia. We shall deal with these regions, and how

they confronted the challenges of a changing world, in Chapters 16

and 17.

358 CHAPTER 14 NEW ENCOUNTERS: THE CREATION OF A WORLD MARKET

SUGGESTED READING

European Expansion On the technological aspects of

European expansion, see C. M. Cipolla, Guns, Sails, and Empires:

Technological Innovation and the Early Phases of European

Expansion, 1400--1700 (New York, 1965); F. Fernandez-Armesto,

ed., The Times Atlas of World Exploration (New York, 1991); and

R. C. Smith, Vanguard of Empire: Ships of Exploration in the Age

of Columbus (Oxford, 1993); also see A. Pagden, Lords of All the

World: Ideologies of Empire in Spain, Britain, and France, c.

1500--c. 1800 (New Haven, Conn., 1995). For an overview of

the impact of European expansion in the Indian Ocean, see

K. N. Chaudhuri, Trade and Civilization in the Indian Ocean:

An Economic History from the Rise of Islam to 1750 (Cambridge,

1985). For a series of stimulating essays reflecting modern

scholarship, see J. D. Tracy, The Rise of Merchant Empires: Long-

Distance Trade in the Early Modern World, 1350--1750

(Cambridge, 1990).

Spanish Activities in the Americas A gripping work on the

conquistadors is H. Thomas, Conquest: Montezuma, Cort

es, and

the Fall of Old Mexico (New York, 1993). The human effects of

the interaction of New and Old World cultures are examined

thoughtfully in A. W. Crosby, The Columbian Exchange: Biological

and Cultural Consequences of 1492 (Westport, Conn., 1972).

Spain’s Rivals On Portuguese expansion, the fundamental

work is C. R. Boxer, The Portuguese Seaborne Empire, 1415--1825

(New York, 1969). On the Dutch, see J. I. Israel, Dutch Primacy in

World Trade, 1585--1740 (Oxford, 1989). British activities are

chronicled in S. Sen, Empire of Free Trade: The East India

Company and the Making of the Colonial Marketplace

(Philadelphia, 1998), and Anthony Wild’s elegant work The East

India Company: Trade and Conquest from 1600 (New York, 2000).

The Spice Trade The effects of European trade in Southeast

Asia are discussed in A. Reid, Southeast Asia in the Age of

Commerce, 1450--1680 (New Haven, Conn., 1989). On the spice

trade, see A. Dalby, Dangerous Tastes: The Story of Spices

(Berkeley, Calif., 2000), and J. Turner, Spice: The History of a

Temptation (New York, 2004).

The Slave Trade On the African slave trade, the standard

work is P. Curtin, The African Slave Trade: A Census (Madison,

Wis., 1969). For more recent treatments, see P. E. Lovejoy,

Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa

(Cambridge, 1983), and P. Manning, Slavery and African Life

(Cambridge, 1990); H. Thomas, The Slave Trade (New York, 1997),

provides a useful overview. Also see C. Palmer, Human Cargoes:

The British Slave Trade to Spanish America, 1700--1739 (Urbana,

Ill., 1981), and K. F. Kiple, The Caribbean Slave: A Biological

History (Cambridge, 1984).

Women For a brief introduction to women’s experiences

during the Age of Exploration and global trade, see S. Hughes and

B. Hughes, Women in World History, vol. 2 (Armonk, N.Y., 1997).

For a more theoretical discussion of violence and gender in the early

modern period, consult R. Trexler, Sex and Conquest: Gendered

Violence, Political Order, and the European Conquest of the

Americas (Ithaca, N.Y., 1995). The native American female

experience with the European encounter is presented in

R. Gutierrez, When Jesus Came the Corn Mothers Went Away:

Marriage, Sexuality, and Power in New Mexico, 1500--1846

(Stanford, Calif., 1991), and K. Anderson, Chain Her by One Foot:

The Subjugation of Women in Seventeenth-Century New France

(London, 1991).

Visit the website for The Essential World History to access study

aids such as Flashcards, Cr itical Thinking Exercises, and

Chapter Quizzes:

www.cengage.com/history/duikspiel/essentialworld6e

CONCLUSION 359

360

CHAPTER 15

EUROPE TRANSFORMED: REFORM AND STATE BUILDING

CHAPTER OUTLINE

AND FOCUS QUESTIONS

The Reformation of the Sixteenth Century

Q

What were the main tenets of Lutheranism and

Calvinism, and how did they differ from each other

and from Catholicism?

Europe in Crisis, 1560--1650

Q

Why is the period between 1560 and 1650 in Europe

called an age of crisis?

Response to Crisis: The Practice of Absolutism

Q

What was absolutism, and what were the main

characteristics of the absolute monarchies that emerged

in France, Prussia, Austria, and Russia?

England and Limited Monarchy

Q

How and why did England avoid the path of

absolutism?

The Flourishing of European Culture

Q

How did the artistic and literary achievements of this

era reflect the political and economic developments

of the period?

CRITICAL THINKING

Q

What was the relationship between European overseas

expansion (as seen in Chapter 14) and political,

economic, and social developments in Europe?

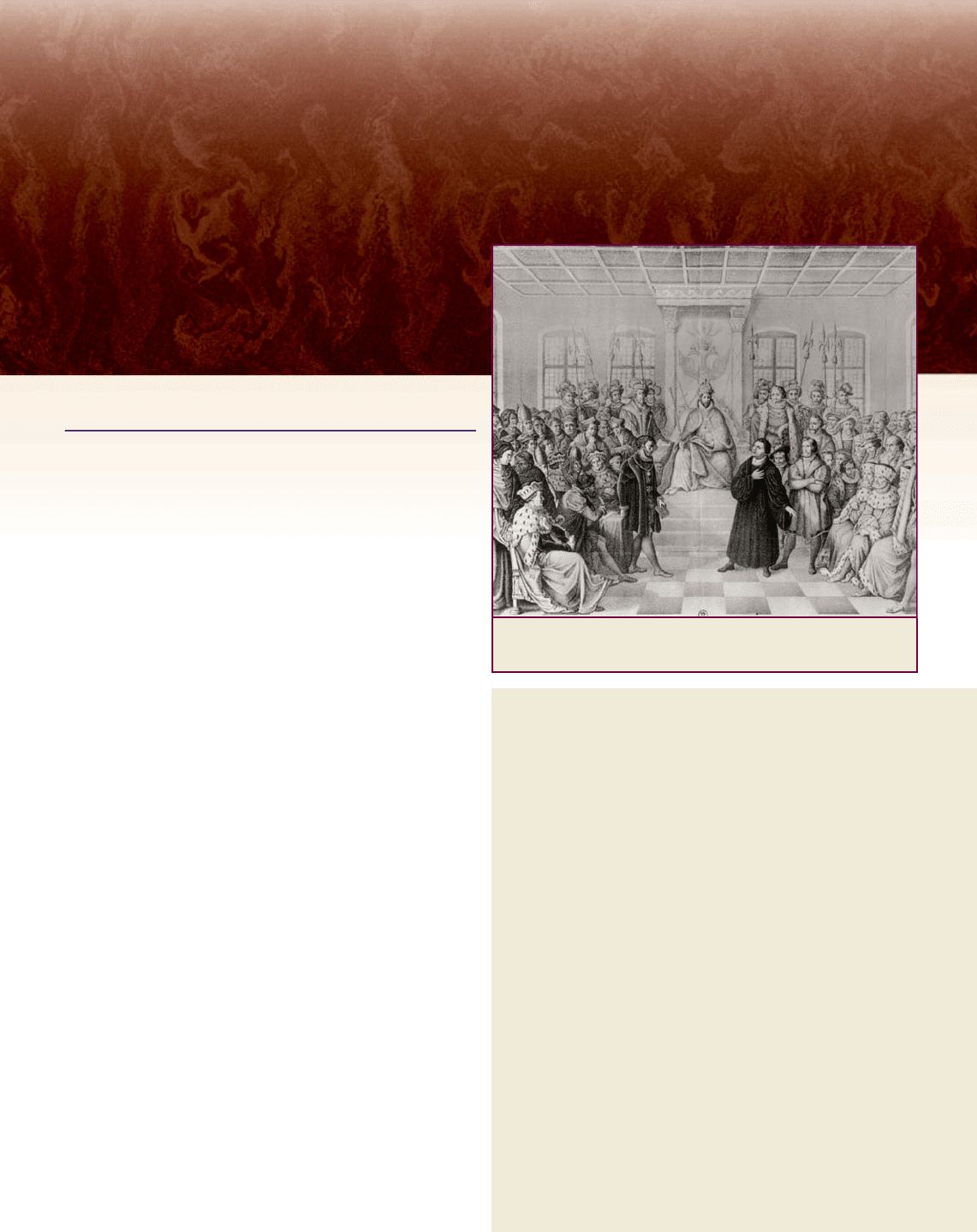

A sixteenth-century engraving of Martin Luther in front

of Charles V at the Diet of Worms

ON APRIL 18, 1521, A LOWLY MONK stood before the

emperor and princes of Germany in the city of Worms. He had

been called before this august gathering to answer charges of heresy,

charges that could threaten his very life. The monk was confronted

with a pile of his books and asked if he wished to defend them all

or reject a part. Courageously, Martin Luther defended them all and

asked to be shown where any part was in error on the basis of

‘‘Scripture and plain reason.’’ The emperor was outraged by Luther’s

response and made his own position clear the next day: ‘‘Not only I,

but you of this noble German nation, would be forever disgraced if

by our negligence not only heresy but the very suspicion of heresy

were to survive. After having heard yesterday the obstinate defense

of Luther, I regret that I have so long delayed in proceeding against

him and his false teaching . I will have no more to do with him.’’

Luther’s appearance at Worms set the stage for a serious challenge

to the authority of the Catholic church. This was by no means the

first crisis in the church’s fifteen-hundred-year history, but its conse-

quences were more far-reaching than anyone at Worms in 1521

could have imagined.

After the disintegrative patterns of the fourteenth century,

Europe began a remarkable recovery that encompassed a revival of

361

c

The Bridgeman Art Library

The Reformation

of the Sixteenth Century

Q

Focus Question: What were the main tenets of

Lutheranism and Calvinism, and how did they differ

from each other and from Catholicism?

The Protestant Reformation is the name given to the

religious reform movement that divided the western

Christian church into Catholic and Protestant groups.

Although Martin Luther began the Reformation in the

early sixteenth century, several earlier developments had

set the stage for religious change.

Background to the Reformati on

Changes in the fifteenth century---the age of the

Renaissance---helped prepare the way for the dramatic

upheavals in sixteenth-century Europe.

The Growth of State Power In the first half of the fif-

teenth centur y, European states had continued the disin-

tegrative patterns of the previous century. In the second

half of the fifteenth century, however, recovery had set in,

and attempts had been made to reestablish the centralized

power of monarchical governments. To characterize the

results, some historians have used the label ‘‘Renaissance

states’’; others have spoken of the ‘‘new monarchies ,’’

especially those of France, England, and Spain at the end

of the fifteenth century (see Chapter 13).

Although appropriate, the term new monarch can

also be misleading. What was new about these Renais-

sance monarchs was their concentration of royal au-

thority, their attempts to suppress the nobility, their

efforts to control the church in their lands, and their

desire to obtain new sources of revenue in order to in-

crease royal power and enhance the military forces at

their disposal. Like the rulers of fifteenth-century Italian

states, the Renaissance monarchs were often crafty men

obsessed with the acquisition and expansion of political

power. Of course, none of these characteristics was en-

tirely new; a number of medieval monarchs, especially in

the thirteenth century, had also exhibited them. Never-

theless, the Renaissance period does mark the further

extension of centralized royal authority.

No one gave better expression to the Renaissance

preoccupation with political power than Niccolo

`

Ma-

chi avelli (1469--1527), an Italian who wrote The Prince

(1513), one of the most influential works on political

power in the Western world. Machiavelli’s major con-

cerns in Th e Prince were the acquisition, maintenance,

and expansion of political power as the means to restore

and maintain order in his time. In the Middle Ages,

many political theorists stressed the ethical side of a

prince’s activity---how a ruler ought to behave based on

Christian moral principles. Machiavelli bluntly contra-

dic ted this a pproach: ‘‘For the gap between how people

actually behave and how they ought to behave is so great

that anyone who ignores everyday reality in order t o live

up to an ideal will soon discover he had been taught

how t o destroy himself, not how to preserve himself.’’

1

Machiavelli was among the first Western thinkers to

aba ndon morality as the basis for the analysis of po lit-

ical activity. The same emphasis on the ends justifying

the means, or on achieving results regardless of the

method s employed , had in fact been expres s e d a thou-

sand year s earlier by a cour t official in Indi a named

Kautilya in his treatise on politics, the Arthasastra (see

Chapter 2).

Social Changes in the Renaissance Social changes in

the fifteenth century also had an impact on the Refor-

mation of the sixteenth century. After the severe eco-

nomic reversals and social upheavals of the fourteenth

century, the European economy gradually recovered as

manufacturing and trade increased in volume.

As noted in Chapter 12, society in the Middle Ages

was divided into three estates: the clergy, or first estate,

whose preeminence was grounded in the belief that

people should be guided to spiritual ends; the nobility, or

second estate, whose privileges rested on the principle

that nobles provided security and justice for society; and

the peasants and inhabitants of the towns and cities, the

362 CHAPTER 15 EUROPE TRANSFORMED: REFORM AND STATE BUILDING

arts and letters in the fifteenth century, known as the Renaissance,

and a religious renaissance in the sixteenth century, known as the

Reformation. The religious division of Europe (Catholics versus

Protestants) that was a result of the Reformation was instrumental

in beginning a series of wars that dominated much of European his-

tory from 1560 to 1650 and exacerbated the economic and social

crises that were besetting the region.

One of the responses to the crises of the seventeenth century

was a search for order. The most general trend was an extension of

monarchical power as a stablizing force. This development, which

historians have called absolutism or absolute monarchy, was most

evident in France during the flamboyant reign of Louis XIV,

regarded by some as the perfect embodiment of an absolute

monarch.

But absolutism was not the only response to the search for

order in the seventeenth century. Other states, such as England,

reacted very differently to domestic crisis, and another very different

system emerged where monarchs were limited by the power of their

representative assemblies. Absolute and limited monarchy were the

two poles of seventeenth-century state building.

third estate. Although this social order continued into the

Renaissance, some changes also became evident.

Throughout much of Europe, the landholding nobles

faced declining real incomes during most of the four-

teenth and fifteenth centuries. Many members of the old

nobility survived, however, and new blood also infused

their ranks. By 1500, the nobles, old and new, who con-

stituted between 2 and 3 percent of the population in

most countries, managed to dominate society, as they had

done in the Middle Ages, holding important political

posts and serving as advisers to the king.

Except in the heavily urban areas of northern Italy

and Flanders, peasants made up the overwhelming mass

of the third estate---they constituted 85 to 90 percent of

the total European population. Serfdom decreased as the

manorial system continued its decline. Increasingly, the

labor dues owed by peasants to their lord were converted

into rents paid in money. By 1500, especially in western

Europe, more and more peasants were becoming legally

free. At the same time, peasants in many areas resented

their social superiors and sought a greater share of the

benefits coming from their labor. In the sixteenth century,

the grievances of peasants, especially in Germany, led

many of them to support religious reform movements.

The remainder of the third estate consisted of the

inhabitants of towns and cities, originally merchants and

artisans. But by the fifteenth century, the Renaissance

town or city had become more complex. At the top of

urban society were the patricians, whose wealth from

capitalistic enterprises in trade, industry, and banking

enabled them to dominate their urban communities

economically, socially, and politically. Below them were

the petty burghers---the shopkeepers, artisans, guild-

masters, and guildsmen---who were largely concerned

with providing goods and services for local consumption.

Below these two groups were the propertyless workers

earning pitiful wages and the unemployed, living squalid

and miserable lives. These poor city-dwellers constituted

30 to 40 percent of the urban population. The pitiful

conditions of the lower groups in urban society often led

them to support calls for radical religious reform in the

sixteenth century.

The Impact of Printing The Renaissance witnessed the

development of printing, which made an immediate

impact on European intellectual life and thought. Print-

ing from hand-carved wooden blocks had been done in

the West since the twelfth century and in China even

before that. What was new in the fifteenth century in

Europe was multiple printing with movable metal type.

The development of printing from movable type was a

gradual process that culminated sometime between 1445

and 1450; Johannes Gutenberg of Mainz played an

important role in bringing the process to completion.

Gutenberg’s Bible, completed in 1455 or 1456, was the

first true book produced from movable type.

By 1500, there were more than a thousand printers in

Europe, who collectively had published almost 40,000

titles (between eight and ten million copies). Probably

half of these books were religious---Bibles and biblical

commentaries, books of devotion, and sermons.

The printing of books en couraged scholarly research

and the desire to attain knowledge. Printing also stimu-

lated the growth of an ever-expanding lay reading public,

a development that had an enormous impact on European

society. Indeed, without the printing press, the new reli-

gious ideas of the Reformation would never have spread as

rapidly as they did in the sixteenth century. Moreover,

printing allowed European civilization to compete for the

first time with the civilization of China.

Prelude to Reformation During the second half of the

fifteenth century, the new Classical learning of the Italian

Renaissance spread to the European countries north of the

Alps and spawned a movement called Christian human-

ism or northern Renaissance humanism, whose major

goal was the reform of Christendom. The Christian hu-

manists believed in the ability of human beings to reason

and improve themselves and thought that through edu-

cation in the sources of Classical, and especially Christian,

antiquity, they could instill an inner piety or an inward

religious feeling that would bring about a reform of the

church and society. To change society, they must first

change the human beings who compose it.

The most influential of all the Christian humanists

was Desiderius Erasmus (1466--1536), who formulated

and popularized the reform program of Christian hu-

manism. He called his conception of religion ‘‘the phi-

losophy of Christ,’’ by which he meant that Christianity

should be a guiding philosophy for the direction of daily

life rather than the system of dogmatic beliefs and prac-

tices that the medieval church seemed to stress. No doubt

his work helped prepare the way for the Reformation; as

contemporaries proclaimed, ‘‘Erasmus laid the egg that

Luther hatched.’’

Church and Religion on the Eve of the Reformation

Corruption in the Catholic church was another factor

that encouraged people to want reform. Between 1450

and 1520, a series of popes---called the Renaissance

popes---failed to meet the church’s spiritual needs. The

popes were supposed to be the spiritual leaders of

the Catholic church, but as rulers of the Papal States, they

were all too often involved in worldly interests. Julius II

(1503--1513), the fiery ‘‘warrior-pope,’’ personally led ar-

mies against his enemies, much to the disgust of pious

THE REFORMATION OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY 363